Abstract

Background

Infective endocarditis is a rare diagnosis in pediatrics. Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes is known to cause a range of type and severity of infections in childhood. However, S. pyogenes is a rarely described cause of endocarditis in children. This paper presents two cases of S. pyogenes endocarditis and the largest and most up-to-date review of cases previously reported in the literature.

Case presentation

Here we describe two pediatric cases of S. pyogenes endocarditis with associated toxic shock. Case 1 was a previously well Caucasian 6-year-old female who presented with sepsis. Case 2 was an 8-month-old South Asian female who presented with sepsis and pneumonia. We present a review of the literature since the beginning of the antibiotic era of this unusual cause of bacterial endocarditis in children.

Conclusion

In addition to the two cases presented here, a total of 13 children have been reported since 1940 with endocarditis caused by S. pyogenes for which clinical details are available. Although few cases exist, literature review reveals a high mortality rate (27%) and the majority of patients who recovered had residual morbidities. We emphasize the importance of considering a diagnosis of endocarditis in cases of S. pyogenes sepsis or toxic shock in order to ensure early diagnosis and timely treatment, which are necessary for good outcomes. This information is relevant to both general and subspecialty pediatricians, especially emergency room and infectious disease physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a rare diagnosis in children. Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes can cause a range of type and severity of infections in childhood including invasive, toxin-mediated, and immune-mediated disease. However, S. pyogenes is a rarely described cause of IE in children. The estimated proportion of IE caused by S. pyogenes in children under age 21 is less than 3% [1]. In addition to the two cases presented here, a total of 13 children have been reported since 1940 with endocarditis caused by S. pyogenes for which clinical details are available. Here we describe two cases of IE caused by S. pyogenes in children with associated toxin-mediated disease, and present a review of the literature since the beginning of the antibiotic era.

Case presentation

Case 1

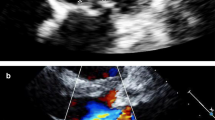

A 6-year-old previously healthy unvaccinated Caucasian female was seen at a rural emergency department (ED) with a 3-week history of fevers and a 3-day history of lethargy, poor oral intake, and erythematous rash. Following discharge from the ED, she re-presented two days later to the same ED with fever and signs consistent with sepsis. She was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) of our tertiary care center after fluid rehydration and one dose of ceftriaxone. At least 3 of her 6 siblings had a recent history of pharyngitis, although only one was seen by a physician, diagnosed clinically as strep throat, and treated. On examination she had a systolic murmur, painful purple nodules of the fingers and toes, and erythema of the palms and soles. She was hypotensive and required dopamine and epinephrine infusions to maintain blood pressure. White blood cell count was 18.7×109/L with 73% neutrophils. Initial electrocardiogram (ECG) was normal. Antimicrobial therapy initiated on admission was vancomycin and meropenem. Transthoracic echocardiogram (echo) was done due to clinical stigmata suspicious for IE, which demonstrated a mobile mass on the posterior mitral leaflet (0.7 cm × 0.5 cm) and a small atrial septal defect (ASD)/patent foramen ovale (PFO). Head computed tomography (CT) revealed multiple bilateral asymmetric hypoattenuating foci, presumed to be septic emboli or watershed infarcts. Once the diagnosis of IE was made, gentamicin was added. Three hours after admission to the ICU, cardiac monitor abnormalities prompted a repeat ECG, which showed accelerated junctional rhythm and atrioventricular (AV) dissociation. The decision was made not to operate, as her echo showed good function and no aortic root abscess. On day 2 of admission, blood cultures drawn at the community hospital came back positive for S. pyogenes. Penicillin (400,000 units/kg/day) and clindamycin were started; gentamicin was discontinued. By day 3 of admission, she had clinically improved and vancomycin and meropenem were stopped. Blood cultures drawn on admission to our institution were sterile. She improved rapidly on penicillin and by day 5 of admission, the suspected toxin-mediated process had resolved, and clindamycin was discontinued. Liver and renal function remained normal. She was discharged home 8 days after presentation and completed 6 weeks of intravenous penicillin (400,000 units/kg/day). Complete resolution of the vegetation was seen on 3-month follow-up echo.

Case 2

A previously well 8-month-old South Asian female presented to a community hospital with a clinical picture suggestive of sepsis. She had a 1-week history of fevers and viral respiratory prodrome and a 2-day history of lethargy and poor oral intake. On initial presentation, she had increased work of breathing and chest x-ray demonstrated a right pleural effusion. She was initially treated with vancomycin, cefotaxime, and oseltamivir. On day 2 of hospitalization, she was intubated due to worsening lethargy, poor perfusion, and acidosis. She was then transferred to the ICU at our tertiary care facility where hemodynamic support was provided and a chest tube was placed. Blood cultures drawn from the community hospital grew S. pyogenes and penicillin (300,000 units/kg/day) and clindamycin were started. Repeat blood cultures at our institution were also positive for S. pyogenes. Due to hemodynamic instability, a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed to assess cardiac function. The study was limited by clinical instability but did not show evidence of endocarditis. In addition to hypotension, she developed multi-organ dysfunction including acute renal failure, elevated liver enzymes, and thrombocytopenia. On day 6 of illness, she had left hand twitching and bilateral abnormal eye movements. Head CT showed extensive bilateral asymmetric foci of white matter diffusion restriction consistent with watershed infarcts and right parietal lobe findings suggestive of hemorrhagic septic emboli. Repeat transthoracic echocardiogram showed a tricuspid valve vegetation and a PFO. High dose penicillin was continued and blood cultures became negative after one week of antibiotic therapy. She was transferred to the ward on day 18 of illness and discharged home after 34 days total. Penicillin (300,000 units/kg/day) was continued to complete 6 weeks, and she had complete resolution of symptoms on follow-up.

Discussion

Infective endocarditis is unusual in children and carries significant morbidity and mortality. S. pyogenes is a rare cause of this condition. This organism is a virulent cause of endocarditis, as the infection has the potential to progress despite appropriate therapy, which can ultimately lead to death [2].

Prior to the antiobiotic era, infective endocarditis was nearly always fatal, regardless of the causal pathogen [3]. Incidence of endocarditis caused by S. pyogenes has declined significantly since the introduction of antiobiotics, largely due to antibiotic treatment of local pyogenic infections preventing bacteremia and seeding of the endocardium [4].

While underlying congenital heart disease is considered a major risk factor for endocarditis [3], the cases we present and the majority of those with S. pyogenes endocarditis reported in the literature occurred in children with structurally normal hearts. This is consistent with the epidemiology of other causes of endocarditis in children, which has shifted in recent years to affect a higher proportion of children without underlying structural heart disease [1].

Bacteremia caused by S. pyogenes comes from a primary source, which may be cellulitis, pharyngitis, endometritis, pneumonia, or other localized pyogenic infection. In children, the primary source is most commonly pharyngitis or skin lesions [5]. Superinfection of varicella skin lesions with S. pyogenes is the most common focus of infection leading to endocarditis by this organism [6, 7]. However, endocarditis as a complication of varicella is very unusual [8]. In Case 1, the portal of entry was likely pharyngitis. Although less clear in Case 2, the initial infection may have been pneumonia.

S. pyogenes can produce multiple exotoxins, which have potential to cause end organ damage or release cytokines that can cause tissue injury [5]. The syndrome of toxic shock caused by S. pyogenes endocarditis is uncommon, especially in children. Both cases we describe are consistent with clinical features of toxic shock. Case 2 fits the accepted definition of toxic shock [9], as she had hypotension as well as multi-organ involvement including renal impairment, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy, and respiratory distress. Case 1 had features of toxic shock including hypotension and a generalized rash; however, the clinical picture does not meet formal criteria [9]. There are few cases of toxic shock associated with S. pyogenes endocarditis in the literature. The case reported by Liu et al. required intubation, vasopressors, and fluid resuscitation, although toxic shock is not specifically discussed [7]. As well, Winterbotham et al. describe a case with hypotension and respiratory failure; however, the details are unclear [5]. In general, few cases described previously were as clinically unstable as those presented here.

Since these two cases presented to our tertiary care facility within two weeks of each other, we analyzed the strains of S. pyogenes to see if the two cases may have been caused by identical strains. The technique used was emm typing by PCR done by the National Microbiology Laboratory [10, 11]. The strains were shown to be different.

Review of the literature

We conducted an electronic literature search using PubMed and restricted to English language but did not place restrictions on search dates. We further examined reference lists in retrieved articles for additional citations not found by the electronic search.

In addition to the two cases presented above, a total of 13 children have been reported since 1940 with endocarditis caused by S. pyogenes for which clinical details are available. In this review, cases from the antibiotic era were included (Table 1). As such, this resulted in the exclusion of several cases that did not have clinical information available, or were presented with inconsistencies or ambiguous nomenclature (Table 1).

Out of 15 cases of S. pyogenes endocarditis with clinical information available (including those presented above), 10 were male (67%) and 5 were female (33%). Ages range from 4 months to 16 years, with a median age of 3 years. Only 2 patients had known pre-existing heart defects. Varicella was a preceding infection in 4 cases (27%), and 6 patients (40%) had no known preceding infection. The most common valves involved were mitral and aortic, with each accounting for approximately 50%. Case 2 is the only reported case in this population with IE affecting the tricuspid valve. Embolic phenomenon occurred in 11 patients (79%), with one not documented. Five patients had cardiac surgery (33%). The mortality rate was 27% and the majority of patients who recovered had residual morbidities.

Conclusions

In summary, we present a rare combination of endocarditis caused by S. pyogenes in two children with previously normal hearts admitted to the same hospital in a two-week time period, both with signs of toxic shock. Our cases show that in cases of S. pyogenes sepsis or toxic shock, consideration should be given to a concurrent diagnosis of endocarditis, even if the heart is structurally normal. When treated with appropriate antimicrobial therapy and supportive care in a timely manner, even severe presentations of S. pyogenes endocarditis and toxic shock can have excellent outcomes.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ parents for publication of these case reports. Consent was documented in the patients’ charts according to The Hospital for Sick Children’s Consent for Publication/Presentation of Case Reports Policy. Copies are available for review upon request.

Abbreviations

- ASD:

-

Atrial septal defect

- AV:

-

Atrioventricular

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- Echo:

-

Echocardiogram

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IE:

-

Infective endocarditis

- PFO:

-

Patent foramen ovale.

References

Day MD, Gauvreau K, Shulman S, Newburger JW: Characteristics of children hospitalized with infective endocarditis. Circulation. 2009, 119: 865-870. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798751.

Patterson HS, Weir MR: GABHS infective endocarditis: case report. Mil Med. 1984, 149: 92-94.

Johnson DH, Rosenthal A, Nadas AS: Bacterial endocarditis in children under 2 years of age. Am J Dis Child. 1975, 129: 183-186.

Ramirez CA, Naraqi S, McCulley DJ: Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus endocarditis. Am Heart J. 1984, 108: 1383-1386. 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90778-6.

Winterbotham A, Riley S, Kavanaugh-McHugh A, Dermody TS: Endocarditis caused by group A β-hemolytic streptococcus in an infant: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1999, 29: 196-198. 10.1086/520153.

Harnden A, Lennon D: Serious suppurative Group A streptococcal infections in previously well children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988, 7: 714-718. 10.1097/00006454-198810000-00010.

Liu VC, Stevenson JG, Smith AL: Group A streptococcus mural endocarditis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992, 11: 1060-1062. 10.1097/00006454-199211120-00016.

Laskey AL, Johnson TR, Dagartzikas MI, Tobias JD: Endocarditis attributable to group A β-hemolytic streptococcus after uncomplicated varicella in a vaccinated child. Pediatrics. 2000, 106 (3): e40-10.1542/peds.106.3.e40.

Breiman RF, Davis JP, Facklam RR, Gray BM, Hoge CW, Kaplan EL, Mortimer EA, Schlievert PM, Schwartz B, Stevens DL, Todd JK: Defining the group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, rationale and consensus definition. JAMA. 1993, 269 (3): 390-391. 10.1001/jama.1993.03500030088038.

Beall B, Gherardi G, Lovgren M, Facklam RR, Forwick BA, Tyrrell GJ: emm and sof gene sequence variation in relation to serological typing of opacity-factor-positive group A streptococci. Microbiology. 2000, 146: 1195-1209.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Streptococcus Laboratory. Streptococcus Laboratory Protocols. [http://www.cdc.gov/streplab/protocol-emm-type.html]

Kehr HL, Adelman M: Acute bacterial endocarditis in infancy. Am J Dis Child. 1942, 64 (3): 487-491.

Gersony WM, Hayes CJ: Bacterial endocarditis in patients with pulmonary stenosis, aortic stenosis, or ventricular septal defect. Circulation. 1977, 56 (2): I84-I87.

Cooper MJ, Silverman NH, Huey E: Group A β-hemolytic streptococcal endocarditis precipitating rupture of sinus of Valsalva aneurysm: Evaluation by two-dimensional, Doppler, and contrast echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1988, 115: 1132-1134. 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90091-9.

Baddour LM: The Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Emerging Infections Network. Infective endocarditis caused by beta-hemolytic streptococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1998, 26: 66-71. 10.1086/516266.

Mohan UR, Walters S, Kroll JS: Endocarditis due to group A β-hemolytic streptococcus in children with potentially lethal sequalae: 2 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2000, 30: 624-625. 10.1086/313727.

Johnson DH, Rosenthal A, Nadas AS: A forty-year review of bacterial endocarditis in infancy and childhood. Circulation. 1975, 51: 581-588. 10.1161/01.CIR.51.4.581.

Sholler GF, Hawker RE, Celermajer JM: Infective endocarditis in childhood. Pediatr Cardiol. 1986, 6: 183-186. 10.1007/BF02310995.

Tyrrell GJ, Lovgren M, Kress B, Grimsrud K: Varicella-associated invasive group A streptococcal disease in Alberta, Canada – 2000–2002. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 40: 1055-1057. 10.1086/428614.

Van Hare GF, Ben-Shachar G, Liebman J: Infective endocarditis in infants and children during the past 10 years: a decade of change. Am Heart J. 1984, 107 (6): 1235-1240. 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90283-7.

Zakrzewski T, Keith JD: Bacterial endocarditis in infants and children. J Pediatr. 1965, 67 (6): 1179-1193. 10.1016/S0022-3476(65)80224-4.

Humpl T, McCrindle BW, Smallhorn JF: The relative roles of transthoracic compared with transesophageal echocardiography in children with suspected infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 41 (110): 2068-2071.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/14/227/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network and Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory for emm typing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DW, HA, and SM participated in the direct care of the patients. DW conducted the literature review and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. HA assisted with manuscript drafting. SM designed the project, edited the manuscript, and provided overall supervision for the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Weidman, D.R., Al-Hashami, H. & Morris, S.K. Two cases and a review of Streptococcus pyogenes endocarditis in children. BMC Pediatr 14, 227 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-227

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-227