Abstract

Backgroud

Retinal racemose hemangioma (RRH) is a rare congenital disorder that often co-occurs with other ocular complications. In this study, we present a case of RRH complicated with retinal vein obstruction in three branches and provide a review of ocular complications and associations with RRH.

Case presentation

One case of RRH is presented. Fundus examination, fluorescein angiography (FFA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the patient identified Group 3 RRH complicated with retinal vein occlusions in the superotemporal, inferotemporal, and inferonasal branches. Macular edema, which causes visual impairment, was detected. A brief literature review was also presented. The PubMed database was searched for RRH or related keywords to find reports of ocular complications or associations published on or before Dec. 31, 2013. A total of 140 papers describing167 RRH cases were found. The mean age of diagnosis was 22.97 years. Ocular complications were mentioned in 32 (19.16%) cases. Retinal vein occlusion (46.88%) was the major ocular complication in RRH, followed by hemorrhage (34.38%). Eight (4.79%) cases were associated with other ocular diseases such as Sturge–Weber syndrome , Morning glory disc anomaly and macroaneurysm.

Conclusions

Although RRH is a relatively non-progressive condition, its complications may lead to vision loss and should be treated in time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Retinal racemose hemangioma (RRH), also called retinal arteriovenous malformation [1, 2] or retinal arteriovenous communication [3], is a congenital, non-hereditary, and sporadic phacomatosis that is characterized by the appearance of dilated and tortuous retinal vessels frequently extending unilaterally from the optic disc to the retinal periphery. Approximately 30% of RRH patients have coexisting arteriovenous malformations in the brain; this condition is known as Wyburn–Mason syndrome or Bonnet–Dechaumme–Blanc syndrome [4–6]. In rare cases, vascular malformations can also be found in the skin, kidneys, bones, and muscles of RRH patients.

RRH was once thought to be untreatable and does not cause hemorrhage. RRH alone may not cause any symptoms, and is thought to cause vision loss via various ocular complications. This paper presents a case of RRH with retinal vein occlusion (RVO) in three branches and provides a review of ocular complications or associations reported in papers published on or before Dec. 31, 2013.

Case presentation

The current study complies with the protocols reviewed and approved by the independent ethics committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Signed consent form was obtained from the patient.

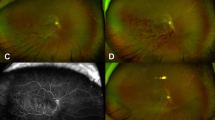

A 58-year old male with sudden onset of blurred vision in his right eye for 10 days was examined in detail. The patient had a visual acuity of 20/100 in his right eye which was not correctable (mydriatic refraction +0.75 DS) at the time of presentation. Direct light reflex of the right pupil was weak. The left eye was refractive amblyopic with a best corrected visual acuity of 20/40 (+3.50 DS) without any other abnormalities. The patient was previously healthy and did not take any medication. The blood pressure was 128/88 mmHg, the blood sugar was 5.67 mmol/l, the blood lipid was slightly higher than normal (triglycerides 2.05 mmol/l, low density lipoprotein cholesterol 4.30 mmol/l). The fundus of the right eye showed a pair of enlarged and tortuous vessels extending from the optic disc. Flame-shaped hemorrhage was found in the temporal and inferior retina, along with dilated retinal veins, whereas macular central reflection was not identified (Figure 1A). FFA examination confirmed the presence of RRH and RVO in the superotemporal, inferotemporal, and inferonasal branches, indicating communication between the pair of tortuous vessels and hypofluorescence caused by hemorrhage and capillary nonperfusion (Figures 1B, 1C). The RRH was found to belong to Group 3 based on Archer’s classification because of the absence of capillary bed between the artery and the vein [3] and because of additional vessel anastomoses in the peripheral retina (Figure 1B, arrowed). OCT examination showed cystoid macular edema (Figure 2A) due to RVO. The retinal surface was uneven in the area of distorted vessels (Figure 2B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed no abnormality, and abdominal ultrasonography was normal despite the presence of a liver cyst.

Fundus and FFA of the diseased eye of the patient. A: The fundus of the right eye showed a pair of enlarged and tortuous vessels extending from the optic disc. Hemorrhage was found in the temporal and inferior retina. B: FFA examination confirmed the presence of RRH and RVO in the superotemporal, inferotemporal, and inferonasal branches. C; The communication between the pair of tortuous vessels at the temporal retina.

Literature review and discussion

Papers dated Dec. 31, 2013 or older were searched using “retinal arteriovenous communication,” “retinal arteriovenous malformations”, “Wyburn–Mason syndrome”, “retinal arteriovenous anastomoses”, “retinal racemose hemangioma”, and “retinal racemose angioma” as keywords in the PubMed database by two persons. The content of each search result was thoroughly checked to ensure its relevance to the topic of the study, especially for papers with ambiguous title. Non-English papers with expressions related to RRH in the English title, abstract, or keywords were included. Papers in Chinese were checked by reading the full text. Papers concerning complications in the eye of patients with RRH were recorded and analyzed.

PubMed search yielded 499 papers related to RRH. Except for reports on “Wyburn–Mason syndrome without retinal involvement”, 140 results (167 cases) were related to RRH, including so called “convoluted vessels”, “twin vessel”, “racemose aneurysm of retina”, and “retinal arteriovenous aneurysm”. Secondary arteriovenous communications were also excluded. Of the 167 cases mentioned in these papers, 152 reported the sex of the subjects (84, 55.26% females and 68, 44.74% males), 128 reported the age of diagnosis (range, 4 to 71 years; mean, 22.97 years), and 3 (1.79%) reported having bilateral occurrence of the disease [7, 8]. Ocular complications or associations are summarized in Table 1. For patients with neovascular glaucoma secondary to RVO, only RVO was recorded. Ocular complications were reported in 32 (19.16%) cases, whereas ocular associations were reported in 8 (4.79%) cases.

Retinal vascular tumors are classified into four clinical categories, including retinal capillary hemangioma, retinal cavernous hemangioma, RRH, and retinal vasoproliferative tumor [35–37]. As a phacomatosis disorder, RRH can manifest at an early age. The average age determined by the current study is 22.97 years old, which is similar to the mean age of 23 years from 27 patients with Wyburn–Mason syndrome reported by Dayani and Sadun [38]. The average age determined by the current study in patients with RRH is significantly younger than the average age of 42 years from 13 RRH patients in the study by Mansour et al. (7), who also reported the disease as “arteriovenous anastomoses of the retina”. Retinal vascular abnormality usually exhibits no symptoms, and is not easily determined compared with malformations in other body parts. Patel (40) reported a case of Wyburn–Mason syndrome with vascular abnormalities in the face, orbit, and brain (but not in the retina) of a newborn. RRH was once thought to be non-progressive, and patients can often continue to have good vision [39, 40]. The longest follow-up period was 27 years without any progression in the retinal or cephalic condition [40]. A case of self-regression was also reported [41]. However, previous reports indicated that vessel dilation and elongation would occur over time in previously normal vessels [42] and that visual impairment would occur because of late ocular complications, particularly ischemic complications [14, 17, 21]. The current study found that RVO is the most common complication of RRH. RVO accounted for 45.46% of the total number of complication cases, while hemorrhage only accounted for 33.33%. Venous occlusion in RRH was attributed mainly to abnormal turbulent blood flow in the veins. In patients with RRH, the veins that connect directly to the arteries are subjected to arterial blood pressure. High blood pressure causes irregular venous wall thickening, endothelial damage and proliferation, and thrombosis [43]. In some cases, severe thrombosis and further fibrosis can cause the malformed vessels to close spontaneously [44–46]. In the present study, the superotemporal, inferotemporal, and inferonasal venous branches were found to converge into a single trunk while the superonasal venous branch drained to another trunk in the disc. This phenomenon is called incomplete central retinal vein occlusion. The elevated level of blood lipid in this patient may also have induced the development of RVO. RVO is also considered a complication of cerebral arteriovenous malformation [47]. RVO and other related macular edema or secondary neovascular glaucoma are all vision-threatening conditions. Although racemose hemangioma is not easily treated, its complications should be handled accordingly to retard vision deterioration. Procedures for slowing vision deterioration include laser therapy for RVO, retrobulbar or intraocular injection of triamcinolone for macular edema, vitrectomy for vitreous hemorrhage, and drainage valve implantation for glaucoma. New anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents have been tested for treatment of malformed vessels or macular edema complicated with RVO [24, 48–50]. However, the association of RRH with other congenital vascular malformations, such as Sturge–Weber syndrome and macroaneurysm, continues to make it a challenging condition for doctors.

Conclusion

As a congenital disorder, RRH may complicate or associate with various ocular conditions; clinicians should pay attention to these conditions and take action to preserve vision.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Abbreviations

- (RRH):

-

Retinal racemose hemangioma

- (RVO):

-

Retinal vein occlusion

- (FFA):

-

Fluorescein angiography

- (OCT):

-

Optical coherence tomography

- (MRI):

-

Magnetic resonance imaging.

References

Hardy TG, O'Day J: Retinal arteriovenous malformation with fluctuating vision and ischemic central retinal vein occlusion and its sequelae: 25-year follow-up of a case. J Neuroophthalmol. 1998, 18 (4): 233-236.

Schatz H, Chang LF, Ober RR, McDonald HR, Johnson RN: Central retinal vein occlusion associated with retinal arteriovenous malformation. Ophthalmol. 1993, 100 (1): 24-30. 10.1016/S0161-6420(93)31701-X.

Archer DB, Deutman A, Ernest JT, Krill AE: Arteriovenous communications of the retina. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973, 75 (2): 224-241.

Wyburn-Mason R: Arteriovenous aneurysm of midbrain and retina, facial nevi and mental changes. Brain Dev. 1943, 66: 40-

Muthukumar N, Sundaralingam MP: Retinocephalic vascular malformation: case report. Br J Neurosurg. 1998, 12 (5): 458-460. 10.1080/02688699844718.

Theron J, Newton TH, Hoyt WF: Unilateral retinocephalic vascular malformations. Neuroradiol. 1974, 7 (4): 185-196. 10.1007/BF00342696.

Mansour AM, Walsh JB, Henkind P: Arteriovenous anastomoses of the retina. Ophthalmol. 1987, 94 (1): 35-40. 10.1016/S0161-6420(87)33505-5.

Soliman W, Haamann P, Larsen M: Exudation, response to photocoagulation and spontaneous remission in a case of bilateral racemose haemangioma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006, 84 (3): 429-431. 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00644.x.

Du B, Gu X, Zeng J: [Retinal vein occlusion with retinal arteriovenous communications]. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 1996, 12 (4): 202-203.

Khairallah M, Allagui M, Chachia N: [Congenital retinal arteriovenous fistula and central retinal vein occlusion]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1993, 16 (2): 117-121.

Zylbermann R, Rozenman Y, Silverstone BZ, Ronen S, Berson D: Central retinal vein occlusion in a case of arteriovenous communication of the retina. Ann Ophthalmol. 1984, 16 (9): 825-828.

Mansour AM, Wells CG, Jampol LM, Kalina RE: Ocular complications of arteriovenous communications of the retina. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989, 107 (2): 232-236. 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070010238029.

Lee AW, Chen CS, Gailloud P, Nyquist P: Wyburn-Mason syndrome associated with thyroid arteriovenous malformation: a first case report. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007, 28 (6): 1153-1154. 10.3174/ajnr.A0512.

Shah GK, Shields JA, Lanning RC: Branch retinal vein obstruction secondary to retinal arteriovenous communication. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998, 126 (3): 446-448. 10.1016/S0002-9394(98)00103-2.

Federici T, Batlle I: Periocular triamcinolone acetonide as treatment for macular edema secondary to branch vein occlusion associated with retinal arteriovenous malformation. Retina. 2006, 26 (9): 1079-1080. 10.1097/01.iae.0000254887.63519.d8.

Yang C, Liu YL, Dou HL, Lu XR, Qian F, Zhao L: Unilateral hemi-central retinal vein obstruction associated with retinal racemose angioma. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2009, 53 (4): 435-436. 10.1007/s10384-009-0673-8.

Salati C, Ferrari E, Basile R, Virgili G, Menchini U: Retinal vein occlusion: late complication of a congenital arteriovenous anomaly. Ophthalmologica. 2002, 216 (2): 151-152. 10.1159/000048316.

Bernth Petersen P: Racemose haemangioma of the retina. Report of three cases with long term follow-up. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1979, 57 (4): 669-678.

Vedantham V, Agrawal D, Ramasamy K: Premacular haemorrhage associated with arteriovenous communications of the retina induced by a valsalva-like mechanism: an observational case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2005, 53 (2): 128-130. 10.4103/0301-4738.16179.

Papageorgiou KI, Ghazi-Nouri SM, Andreou PS: Vitreous and subretinal haemorrhage: an unusual complication of retinal racemose haemangioma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006, 34 (2): 176-177. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01178.x.

Effron L, Zakov ZN, Tomsak RL: Neovascular glaucoma as a complication of the Wyburn-Mason syndrome. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1985, 5 (2): 95-98.

Bloom PA, Laidlaw A, Easty DL: Spontaneous development of retinal ischaemia and rubeosis in eyes with retinal racemose angioma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993, 77 (2): 124-125. 10.1136/bjo.77.2.124.

De Jong PT: Neovascular glaucoma and the occurrence of twin vessels in congenital arteriovenous communications of the retina. Doc Ophthalmol. 1988, 68 (3–4): 205-212.

Winter E, Elsas T, Austeng D: Anti-VEGF treating macular oedema caused by retinal arteriovenous malformation - a case report. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012, 92 (2): 192-193.

Onder HI, Alisan S, Tunc M: Serous Retinal Detachment and Cystoid Macular Edema in a Patient with Wyburn-Mason Syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol. 2013, Epub ahead of print

Medina FM, Maia OO, Takahashi WY: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in Wyburn-Mason syndrome: case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010, 73 (1): 88-91. 10.1590/S0004-27492010000100017.

Cordonnier M, Van Nechel C, Baleriaux D, Brotchi J: [Association of the Wyburn-Mason and morning glory syndromes]. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 1987, 225 (Pt 2): 63-69.

Brodsky MC, Wilson RS: Retinal arteriovenous communications in the morning glory disc anomaly. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995, 113 (4): 410-411. 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100040024015.

Munoz FJ, Rebolleda G, Cores FJ, Bertrand J: Congenital retinal arteriovenous communication associated with a full-thickness macular hole. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1991, 69 (1): 117-120.

Shin GS, Demer JL: Retinal arteriovenous communications associated with features of the Sturge-Weber syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994, 117 (1): 115-117.

Ward JB, Katz NN: Combined phakomatoses: a case report of Sturge-Weber and Wyburn-Mason syndrome occurring in the same individual. Ann Ophthalmol. 1983, 15 (12): 1112-1116.

Manger CC, Ober RR: Retinal arteriovenous anastomoses in the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980, 89 (2): 186-191.

Vucic D, Kalezic T, Kostic A, Stojkovic M, Risimic D, Stankovic B: Duane type I retraction syndrome associated with Wyburn-Mason syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2013, 34 (1–2): 61-64.

Tilanus MD, Hoyng C, Deutman AF, Cruysberg JR, Aandekerk AL: Congenital arteriovenous communications and the development of two types of leaking retinal macroaneurysms. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991, 112 (1): 31-33.

Singh AD, Rundle PA, Rennie I: Retinal vascular tumors. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2005, 18 (1): 167-176. 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.07.005. x

Turell ME, Singh AD: Vascular tumors of the retina and choroid: diagnosis and treatment. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010, 17 (3): 191-200. 10.4103/0974-9233.65486.

De Laey JJ, Hanssens M, Brabant P, Decq L, De Gersem R, Hoste A, Huyghe P, Lenaerts V, Leys M, Pollet L: Vascular tumors and malformations of the ocular fundus. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 1990, 225 (Pt 1): 1-241.

Dayani PN, Sadun AA: A case report of Wyburn-Mason syndrome and review of the literature. Neuroradiol. 2007, 49 (5): 445-456. 10.1007/s00234-006-0205-x.

Leitao Guerra RL, Leitao Guerra CL, Guerra M, Guerra Neto AS, Leitao Guerra AA: [Retinal racemose hemangioma (Wyburn-Mason syndrome)–a patient ten years follow-up: case report]. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2009, 72 (4): 545-548. 10.1590/S0004-27492009000400022.

Schmidt D, Agostini H, Schumacher M: Twenty-seven years follow-up of a patient with congenital retinocephalofacial vascular malformation syndrome and additional congenital malformations (Bonnet-Dechaume-Blanc syndrome or Wyburn-Mason syndrome). Eur J Med Res. 2010, 15 (2): 89-91.

Dekking HM: Arteriovenous aneurysm of the retina with spontaneous regression. Ophthalmologica. 1955, 130 (2): 113-115. 10.1159/000302653.

Pauleikhoff D, Wessing A: Arteriovenous communications of the retina during a 17-year follow-up. Retina. 1991, 11 (4): 433-436.

Pile-Spellman JM, Baker KF, Liszczak TM, Sandrew BB, Oot RF, Debrun G, Zervas NT, Taveras JM: High-flow angiopathy: cerebral blood vessel changes in experimental chronic arteriovenous fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986, 7 (5): 811-815.

Cameron ME, Greer CH: Congenital arterio-venous aneurysm of the retina. A post mortem report Br J Ophthalmol. 1968, 52 (10): 768-772. 10.1136/bjo.52.10.768.

Knecht PB, Bosch MM, Helbig H: Fibrotic racemose haemangioma of the retina. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2008, 225 (5): 495-496. 10.1055/s-2008-1027350.

Gregersen E: Arteriovenous aneurysm of the retina. A case of spontaneous thrombosis and healing. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1961, 39: 937-939.

Hashimoto M, Yokota A, Matsuoka S, Tsukamoto Y, Higashi J: Central retinal vein occlusion after treatment of cavernous dural arteriovenous malformation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989, 10 (5 Suppl): S30-S31.

Chuang LH, Wang NK, Chen YP, Wu WC, Lai CC: Mature vessel occlusion after anti-VEGF treatment in a retinal arteriovenous malformation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013, 13 (1): 60-10.1186/1471-2415-13-60.

Knutsson KA, De Benedetto U, Querques G, Del Turco C, Bandello F, Lattanzio R: Primitive retinal vascular abnormalities: tumors and telangiectasias. Ophthalmologica. 2012, 228 (2): 67-77. 10.1159/000338230.

Mitry D, Bunce C, Charteris D: Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 1: CD009510-

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2415/14/101/prepub

Acknowledgements

The Project was sponsored partly by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2012HM024) and Independent Innovation Foundation to Universities and Colleges by Jinan Science and Technology Bureau (201202036). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

XJQ conceived the study; XJQ and CH conducted the clinical examinations; XJQ and KL conducted the PubMed search, data analysis, and data interpretation; XJQ, CH, and KL wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, Xj., Huang, C. & Lai, K. Retinal vein occlusion in retinal racemose hemangioma: a case report and literature review of ocular complications in this rare retinal vascular disorder. BMC Ophthalmol 14, 101 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2415-14-101

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2415-14-101