Abstract

Background

Persistent infection with high-risk (HR) human papillomavirus (HPV) causes cervical cancer, the fourth most frequent cancer in the Kingdom of Bahrain, with an annual incidence of four per 100,000 women. The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and type distribution of HPV in Bahraini and non-Bahraini women attending routine screening. HPV prevalence was assessed by risk factors and age distribution. Health-related behaviors and HPV awareness were also studied.

Methods

This observational study was conducted between October 2010 and November 2011 in the Kingdom of Bahrain (NCT01205412). Women aged either ≥20 years attending out-patient health services for routine cervical screening or ≥16 years attending post-natal check-ups were enrolled. Cervical samples were collected and tested for HPV-DNA by polymerase chain reaction and typed using the SPF10 DEIA/LiPA25 system. All women completed two questionnaires on health-related behavior (education level, age at first marriage, number of marital partners, parity and smoking status) and HPV infection awareness.

Results

HPV DNA was detected in 56 of the 571 women included in the final analysis (9.8%); 28 (4.9%), 15 (2.6%) and 13 (2.3%) women were infected with single, multiple and unidentifiable HPV types, respectively. The most prevalent HPV types among the HPV positive women were HR-HPV-52 in eight (1.4%), HR-HPV-16, -31 and -51 in six women each (1.1%); low-risk (LR)-HPV-6 in four (0.7%); and LR-HPV-70, -74 in three women each (0.5%). Co-infection with other HR-HPV types was observed in 50% HPV-16-positive women (with HPV-31, -45 and -56) and in both HPV-18-positive women (with HPV-52). None of the health-related risk factors studied were associated with any HR-HPV infection. More than half of women (68.7%) had never heard about HPV, but most women (91.3%) in our study were interested in HPV-vaccination.

Conclusion

HPV prevalence in Bahraini women was 9.8%. The most frequently observed HPV types were HR-HPV-52, -16, -31 and -51 and LR-HPV-6, -70 and -74. These are useful baseline data for health authorities to determine the potential impact of preventive measures including the use of prophylactic vaccines to reduce the burden of cervical cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, cervical cancer (CC) is the second most frequent cancer in women, with an estimated 1.6 million women diagnosed with CC between 2004 and 2008 [1]. In the Kingdom of Bahrain, 369,821 women aged under 15 years are at a risk of CC [2]. CC ranks as the third most frequent cause of cancer in women with a crude annual incidence of four per 100,000 women in the Kingdom of Bahrain [2–4]. Twenty two new cases of CC are diagnosed every year and CC causes approximately 5 deaths annually in the Kingdom of Bahrain [2].

It is well established that persistent infection with high-risk (HR) human papillomavirus (HPV) causes CC [5, 6]. Globally, HR-HPV types -16 and -18 are responsible for almost 70% of the overall CC cases [7], but HR-HPV types -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, -59, -68, -73 and -82; and low-risk (LR) HPV-types -6, -11, -40, -42, -43, -44, -54, -61, -70, -72, -81, and CP6108 have also been associated with the disease [6]. A previous study conducted at two medical centers in the Kingdom of Bahrain observed cervical HPV infection in approximately 11% of women [8].

Two prophylactic HPV vaccines are currently licensed in many countries: bivalent Cervarix® (GlaxoSmithKline, Belgium) and quadrivalent Gardasil® (Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, New Jersey). Both vaccines are well tolerated with good efficacy profiles in preventing HPV infection [9–16].

As baseline data on HPV epidemiology and distribution of HPV types in Bahrain are lacking, it is not possible to accurately assess the disease burden associated with CC and it is therefore difficult to measure the impact of preventive measures, such as the introduction of vaccination. This study was designed to evaluate the prevalence and type distribution of HPV in Bahraini women. The study also evaluated HPV type distribution by risk category in women of different ages, and also documented the awareness of HPV infection, vaccination and health-related behaviors through questionnaires.

Methods

Study design and population

This observational, cross-sectional, study was conducted in the Kingdom of Bahrain between October 2010 and November 2011 (NCT01205412) at four primary healthcare centers (Isa town Heath Center, Arad Health Center, Budaiya Health Center, Sitra Health Center) and the American Mission Hospital. Women aged either ≥20 years undergoing routine cervical screening or ≥16 years attending post-natal check-ups and willing to provide a cervical sample were enrolled. Women were excluded for: immunosuppression, abnormal cervical samples, heavy menstrual bleeding that would interfere with screening, hysterectomy, previous HPV vaccination or pregnancy.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee in the Ministry of Health. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Informed consent was obtained from all eligible women before enrollment.

Sample collection and laboratory procedures

Endocervical samples, collected by a trained practitioner/gynecologist using a cytobrush, were preserved in Thinprep® (Hologic, Inc) solution and stored on-site at room temperature for four weeks before shipment at -20°C to the DDL Diagnostic Laboratory (Rijswijk, the Netherlands).

HPV-DNA isolated from cervical samples (500 μl) using the MagNA Pure LC Total NAILV kit (Roche Diagnostics, Almere, The Netherlands) and eluted in buffer (50 μl) [17] were typed using broad-spectrum polymerase chain reaction (PCR). HPV short PCR fragment 10 (SPF10) and PCR DNA enzyme immunoassay (PCR-DEIA) were used to amplify and hybridize with a cocktail of nine conservative probes to identify at least 57 HPV genotypes. DEIA positive- Line probe assay (LiPA) negative samples were denoted as ‘non-typeable/unidentifiable’ HPV types.

LiPA25 version 1 system (Labo Biomedical Products, Rijswijk, the Netherlands) was also used to genotype 25 HR and LR HPV types (14 HR [HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, -59, -66 and -68] and 11 LR-HPV types [HPV-6, -11, -34, -40, -42, -43, -44, -53, -54, -70 and -74]) [18]. Sequence variation within the SPF10 inter-primer region did not allow a distinction between HPV types -68 and -73 [19].

All women completed two questionnaires which assessed health-related behavior and their awareness of HPV.

Statistical analyses

The primary objective was to estimate the prevalence of any HPV-DNA and HPV types (including multiple infections) among Bahraini and non-Bahraini women aged ≥20 years attending clinics for routine cervical screening or those ≥16 years of age visiting clinics for post-natal check-up. The secondary objectives were to describe HPV type distribution by risk categories (including HR and LR types [20]) according to age and baseline characteristics and to understand health-related behaviors and HPV infection awareness in this population.

Based on an HPV prevalence rate of 11% in the Kingdom of Bahrain in 2006 [8], and allowing for 10% of non-evaluable women, based on cytological precision (2.5%–3.0%), the target enrolment was 460–660 women. Each age group (16–19, 20–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54 and ≥55 years) required a minimum of 75 women.

The percentage of HPV-positive women was tabulated with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Descriptive analyses on HPV prevalence, HPV-types, age distribution, potential risk factors (education level, age at first marriage, marital partners over life-time, parity and smoking status) and HPV status were performed.

An exploratory analysis was undertaken to study the association between the HPV status and nationality using adjusted odds ratio from a multiple logistic regression model and the association between risk factors and HPV prevalence using multivariate analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical analysis software (SAS®) version 9.2.

Results

Study population

Of 577 enrolled women, 571 were included in the final analysis (cervical samples from six were not collected or tested). The mean age (standard deviation) was 35.57 (±11.19) years and the majority (81.3%; 464/571) were Bahraini nationals (Table 1). From the data available from 553 women, 11 women were single, 513 were married 7 were divorced or separated and 20 women were widowed.

HPV Overall prevalence and type distribution

HPV DNA was detected in 56 women (9.8%; 95% CI: 7.5–12.5). Among these, 28 (4.9%; 95% CI: 3.3–7.0) had single HPV-type infection and 15 (2.6%; 95% CI: 1.5–4.3) had multiple HPV-type infection. Thirteen women (2.3%; 95% CI: 1.2–3.9) were infected with unidentifiable HPV-types.

The most prevalent HR-HPV types were HPV-52 in eight women (1.4%) and HPV-16, -31 and -51 each in six women (1.1%). HR-HPV-18 was observed in two women (0.4%).

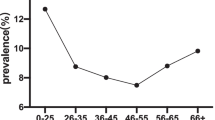

The most prevalent LR types were HPV-6 in four women (0.7%) and HPV-70 and -74 each in three subjects (0.5%) (Figure 1). The prevalence of HPV was similar across all age groups (Table 2), HR-HPV was most frequently observed (25%) in women aged 16–19 years (Figure 2).

HPV DNA prevalence and type distribution among HPV positive women

Among the 56 HPV-positive women, infection with single, multiple and unidentifiable HPV type infection was observed in 50% (95% CI: 36.3–63.7; 28/56), 26.8% (95% CI: 15.8–40.3; 15/56) and 23.2% (95% CI: 13.0–36.4; 13/56), respectively.

Among those infected with HPV, 14.3% (8/56) women were infected with HR-HPV-52, followed by 10.7% (6/56) each with HR-HPV types -16, -31 and -51; HR-HPV-18 was detected in 3.6% women (2/56). The most prevalent LR-HPV types were LR-HPV-6 (7.1% [4/56]), and LR-HPV-70 and -74 (5.4% [3/56] each).

HPV Co-infection

Three of the six women infected with HPV-16 (50%) were co-infected with other HR-HPV types (HPV-16/31, HPV-16/45 and HPV-16/56, respectively). Both HPV-18 infected women were co-infected with HR HPV-52.

Risk factors and awareness

The percentage of Bahraini women positive for HPV as compared to the non-Bahraini women was 6.7% (31/464) vs. 23.4% (25/107), respectively. When other risk factors (age at sample collection, education level, number of marital partners, parity, smoking status) were adjusted, non-Bahraini women had a higher risk of HPV infection in comparison with Bahraini women (adjusted odds ratio: 3.7 [95% CI: 1.9–7.6]; p-value = 0.0002) (Table 3).

None of the studied risk factors were significantly associated with either HPV-16 or HPV-18 or any HR-HPV infection as identified from questionnaire data using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

HPV awareness questionnaire was collected to understand the level and accuracy of awareness regarding cause, transmission and prevention of HPV infection. Among the women who completed this questionnaire, 68.7% (369/537) had never heard about HPV. However 80.9% (432/534) of women believed that it is possible to prevent CC and the majority (91.3%, 495/542) showed an interest in vaccination (Table 4).

Discussion

CC is associated with a considerable disease burden in the Kingdom of Bahrain and represents an important health concern among the female population [2–4]. This study provides a recent estimate of the prevalence and type distribution of both HR- and LR-HPV in Bahraini and non-Bahraini women from 16 years of age. The findings from our study suggest that nearly 10% of women in the Kingdom of Bahrain harbored HPV-DNA, which is consistent with previous estimates of 11% [8] and 12.1% [2]. This prevalence is higher than that reported in Kuwait (2.4%) [21] and Saudi Arabia (5.6%) [22], but is in within the 0–25% range reported for women with normal cytology across the extended Middle East and North Africa [23].

The most prevalent HPV types observed in our study: HR-HPV-52, -16, -31 and -51 and LR-HPV-6, -70 and -74 are consistent with worldwide estimates of circulating HPV types causing CC [7, 24]. Although previous reports indicate that HR-HPV-16 and -18 cause the majority of CC cases worldwide [7], in our study, the overall prevalence of HR-HPV-18 was very low (0.4%). However, since the number of women positive for HPV DNA itself was low (n = 56), our results need to be interpreted with caution.

The highest prevalence of HR-HPV types (25%) was observed in 16–19 year old women, which is in accordance with published worldwide meta-analyses [24, 25] which reported higher HR-HPV type prevalence among women younger than 25 years of age. Other studies from the extended Middle East and North Africa also support our findings, whereby HPV prevalence was highest after sexual debut (20–24 years) but decreased with age [23].

None of the risk factors assessed in our study (education level, age at first marriage, number of marital partners over life time, parity and smoking status) were associated with the presence of HR-HPV types including HPV-16 or HPV-18.

Among the women who completed the health-related behavior and awareness of HPV questionnaire, the majority (68.7%) had no prior knowledge of HPV. In a previous study of Egyptian women, only 1.5% of the urban population underwent routine cervical screening tests, indicating a low awareness level of HPV [26]. Although the vast majority (88.6%) of Bahraini population live in urban areas [2], it is clear that effective measures are needed to increase the awareness of HPV. The willingness of women to receive vaccination against HPV, as observed in this study, might support the measures to prevent HPV infection.

Bivalent and quadrivalent HPV vaccines have been shown to protect against HR-HPV-16 and -18 [10, 13]. Although both prophylactic HPV vaccines have been licensed in the Kingdom of Bahrain since 2009 [2], they have not been included in the national immunization program and their use is limited to private clinics. The estimated disease burden, prevalence and type distribution of HPV data from our study might therefore highlight the need to include prophylactic HPV vaccines which offer broader protection into routine immunization programs.

The main strengths of our study were: the inclusion of both Bahraini and non-Bahraini citizens, enabling an assessment of HPV prevalence among the entire population; and the absence of age group restriction, which allowed us to study a wide age-range. Furthermore, the primary healthcare centers and the hospital were recognized by the Ministry of Health as reference hospitals. The population visiting these centers represented 90% of the local population and our results are representative of the Kingdom of Bahrain considering we met estimated sample size to determine the HPV prevalence in the target population (including nationals and non-national women). The possibility of selection bias is acknowledged in our study as there are some differences between Bahraini and non-Bahraini women to be considered. Most of non-Bahraini are married expatriate, while single females stay only for few years and were more unlikely to be enrolled in the study. However, all women were invited to participate regardless of their nationality and there were no differences in the acceptance rate between nationals and non-nationals identified. Furthermore, the primary healthcare centers were recognized by the Ministry of Health as reference hospitals and there are no differences reported in the use and access for health services, especially for post-natal and screening among women in the country. Lastly, considering the design of the study these results correspond to a single point of time and as HPV infections may be transient and spontaneously resolve [27], the prevalence of HPV might therefore vary with time.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of HPV in Bahrain was 9.8%. The most common HR-HPV types were -52, -16, -31 and -51 and LR-HPV types -6, -70 and -74. The data presented in our study might help healthcare authorities determine the impact of introducing preventive measures, such as prophylactic vaccination, to reduce the burden of CC in the Kingdom of Bahrain.

Trademark

Cervarix is a trademark of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

Gardasil is a trademark of Merck & Co. Inc.

Thinprep is a trademark of Hologic, Inc.

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

Cervical Cancer

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DEIA:

-

DNA Enzyme Immunoassay

- HPV:

-

Human Papillomavirus

- HR:

-

High-Risk

- LiPA25:

-

Line Probe Assay 25

- LR:

-

Low-Risk

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- SPF-10:

-

Short PCR Fragment 10.

References

Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J: Estimates of global cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013, 132 (5): 1133-1145. 10.1002/ijc.27711.

Bruni L, Barrionuevo-Rosas L, Serrano B, Brotons M, Albero G, Cosano R, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Castellsagué X, ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre): Human papillomavirus and related diseases in Bahrain. Summary Report 2014-08-22. [http://www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/BHR.pdf] Data Accessed: 28 November 2014

Ministry of Health Bahrain: Ten years cancer incidence among nationals of the GCC States 1998–2007. Gulf Center for Cancer Control and Prevention, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center [http://www.moh.gov.bh/pdf/publications/GCC%20Cancer%20Incidence%202011.pdf] Data Accessed: 28 November 2014

Abduljabbar A, Al-Rawahi F, Faqihi F, Al-Khayat M, Al-Mahmeed M, Al-Khazali M, Al-Sayed N, AlGhaffar S, AlNasir F: Types and risk factors of cervical cancer. Bahrain Med Bulletin. 2014, 36 (2): 94-96. 10.12816/0004484.

Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N: Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999, 189 (1): 12-19. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F.

Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ: International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study G: Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348 (6): 518-527. 10.1056/NEJMoa021641.

de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, Geraets DT, Klaustermeier JE, Lloveras B, Tous S, Felix A, Bravo LE, Shin HR, Vallejos CS, de Ruiz PA, Lima MA, Guimera N, Clavero O, Alejo M, Llombart-Bosch A, Cheng-Yang C, Tatti SA, Kasamatsu E, Iljazovic E, Odida M, Prado R, Seoud M, Grce M, Usubutun A, Jain A, Suarez GA, Lombardi LE, Banjo A, et al: Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11 (11): 1048-1056. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70230-8.

Hajjaj AA, Senok AC, Al-Mahmeed AE, Issa AA, Arzese AR, Botta GA: Human papillomavirus infection among women attending health facilities in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Saudi Med J. 2006, 27 (4): 487-491.

Descamps D, Hardt K, Spiessens B, Izurieta P, Verstraeten T, Breuer T, Dubin G: Safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine for cervical cancer prevention: a pooled analysis of 11 clinical trials. Hum Vaccin. 2009, 5 (5): 332-340. 10.4161/hv.5.5.7211.

Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmerón J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsague X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Hedrick J, Jaisamrarn U, Limson G, Garland S, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, Bosch FX, Jenkins D, Hardt K, Zahaf T, Descamps D, Struyf F, Lehtinen M, Dubin G, HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009, 374 (9686): 301-314. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4.

Einstein MH, Baron M, Levin MJ, Chatterjee A, Fox B, Scholar S, Rosen J, Chakhtoura N, Meric D, Dessy FJ, Datta SK, Descamps D, Dubin G, HPV-010 Study Group: Comparative immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 vaccine and HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine: follow-up from months 12–24 in a Phase III randomized study of healthy women aged 18–45 years. Hum Vaccin. 2011, 7 (12): 1343-1358. 10.4161/hv.7.12.18281.

Verstraeten T, Descamps D, David MP, Zahaf T, Hardt K, Izurieta P, Dubin G, Breuer T: Analysis of adverse events of potential autoimmune aetiology in a large integrated safety database of AS04 adjuvanted vaccines. Vaccine. 2008, 26 (51): 6630-6638. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.049.

Castellsagué X, Muñoz N, Pitisuttithum P, Ferris D, Monsonego J, Ault K, Luna J, Myers E, Mallary S, Bautista OM, Bryan J, Vuocolo S, Haupt RM, Saah A: End-of-study safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in adult women 24–45 years of age. Br J Cancer. 2011, 105 (1): 28-37. 10.1038/bjc.2011.185.

Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Wheeler CM, Jaisamrarn U, Garland SM, Castellsagué X, Skinner SR, Apter D, Naud P, Salmerón J, Chow SN, Kitchener H, Teixeira JC, Hedrick J, Limson G, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, De Carvalho NS, Germar MJ, Peters K, Mindel A, De Sutter P, Bosch FX, David MP, Descamps D, Struyf F, Dubin G, HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13 (1): 89-99. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70286-8.

Roteli-Martins CM, Naud P, De Borba P, Teixeira JC, De Carvalho NS, Zahaf T, Sanchez N, Geeraerts B, Descamps D: Sustained immunogenicity and efficacy of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: up to 8.4 years of follow-up. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012, 8 (3): 390-397. 10.4161/hv.18865.

Wheeler CM, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, Szarewski A, Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmerón J, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Jaisamrarn U, Limson G, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, Bosch FX, Harper DM, Huh W, Hardt K, Zahaf T, Descamps D, Struyf F, Dubin G, Lehtinen M, HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Cross-protective efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by non-vaccine oncogenic HPV types: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13 (1): 100-110. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70287-X.

Geraets DT, van Baars R, Alonso I, Ordi J, Torne A, Melchers WJ, Meijer CJ, Quint WG: Clinical evaluation of high-risk HPV detection on self-samples using the indicating FTA-elute solid-carrier cartridge. J Clin Virol. 2013, 57 (2): 125-129. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.02.016.

van Doorn LJ, Molijn A, Kleter B, Quint W, Colau B: Highly effective detection of human papillomavirus 16 and 18 DNA by a testing algorithm combining broad-spectrum and type-specific PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44 (9): 3292-3298. 10.1128/JCM.00539-06.

Kleter B, van Doorn LJ, Schrauwen L, Molijn A, Sastrowijoto S, ter Schegget J, Lindeman J, ter Harmsel B, Burger M, Quint W: Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1999, 37 (8): 2508-2517.

de Cremoux P, de la Rochefordière A, Savignoni A, Kirova Y, Alran S, Fourchotte V, Plancher C, Thioux M, Salmon RJ, Cottu P, Mignot L, Sastre-Garau X: Different outcome of invasive cervical cancer associated with high-risk versus intermediate-risk HPV genotype. Int J Cancer. 2009, 124 (4): 778-782. 10.1002/ijc.24075.

Al-Awadhi R, Chehadeh W, Kapila K: Prevalence of human papillomavirus among women with normal cervical cytology in Kuwait. J Med Virol. 2011, 83 (3): 453-460. 10.1002/jmv.21981.

Bondagji NS, Gazzaz FS, Sait K, Abdullah L: Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infections in healthy Saudi women attending gynecologic clinics in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2013, 33 (1): 13-17.

Seoud M: Burden of human papillomavirus-related cervical disease in the extended middle East and north Africa-a comprehensive literature review. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012, 16 (2): 106-120. 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31823a0108.

Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S: Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. 2010, 202 (12): 1789-1799. 10.1086/657321.

de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Munoz N, Bosch FX: Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007, 7 (7): 453-459. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5.

el-All HS, Refaat A, Dandash K: Prevalence of cervical neoplastic lesions and Human Papilloma Virus infection in Egypt: National Cervical Cancer Screening Project. Infect Agent Cancer. 2007, 2: 12-10.1186/1750-9378-2-12.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HPV Provider Survey: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices about genital HPV infection and related conditions. June 14, 2005. [http://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/HPVProviderSurveyExecSum.pdf] Data Accessed: 28 November 2014

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/905/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following investigators for their contributions: Dr. Amina Al-Balooshi, Dr. Shereen Mohamed, Dr. Ebtisam Rabia, Dr. Zahra Al-Mussali and Dr. Mohammed AlKhateeb for study site coordination.

The authors also thank Karin Hallez and Runa Mithani for study coordination and administration support, Shruti Priya Bapna and Harshith Bhat (employed by GlaxoSmithKline group of companies) for preparing the manuscript, Julia Donnelly (freelance on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) for language editing and Abdelilah Ibrahimi (XPE Pharma and Science on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines) for publication coordination.

Funding source

This study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis and also funded all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present manuscript. The authors had full access to the data and the corresponding author was responsible for submission of the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

KM and AM received grants from GSK Biologicals for the conduct of the study. RD and KG are employed by GlaxoSmithKline group of companies and RD owns stock options. WQ has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

KM and AM conducted the study and were involved in protocol design, supervision of the study, analysis and interpretation of the study results. WQ was involved in the genotyping, analysis and interpretation of the results. KG contributed to the conception of the study and performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results and report. RD was responsible of the study and contributed to the analysis, interpretation and drafting of the study report. All authors have reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Moosa, K., Alsayyad, A.S., Quint, W. et al. An epidemiological study assessing the prevalence of human papillomavirus types in women in the Kingdom of Bahrain. BMC Cancer 14, 905 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-905

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-905