Abstract

Background

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the primary motor cortex has been shown to modulate pain and trigeminal nociceptive processing.

Methods

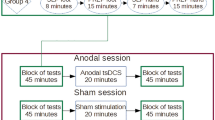

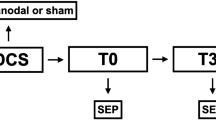

Ten patients with classical trigeminal neuralgia (TN) were stimulated daily for 20 minutes over two weeks using anodal (1 mA) or sham tDCS over the primary motor cortex (M1) in a randomized double-blind cross-over design. Primary outcome variable was pain intensity on a verbal rating scale (VRS 0–10). VRS and attack frequency were assessed for one month before, during and after tDCS. The impact on trigeminal pain processing was assessed with pain-related evoked potentials (PREP) and the nociceptive blink reflex (nBR) following electrical stimulation on both sides of the forehead before and after tDCS.

Results

Anodal tDCS reduced pain intensity significantly after two weeks of treatment. The attack frequency reduction was not significant. PREP showed an increased N2 latency and decreased peak-to-peak amplitude after anodal tDCS. No severe adverse events were reported.

Conclusion

Anodal tDCS over two weeks ameliorates intensity of pain in TN. It may become a valuable treatment option for patients unresponsive to conventional treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Several studies showed that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) modulates the cortical excitability of the motor cortex depending on the direction of the electric current (e.g. anodal or cathodal) and that its neuroplastic effects sustain after stimulation[1]. The primary effect of tDCS is a modulation of the membrane potential of neurons in the stimulated cortical area[2, 3], mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDA-R)[4]. Nonetheless, the effects of tDCS on cortical excitability can spread to distant cortical areas possibly along interconnections between the stimulated area and adjacent regions[5]. It was suggested, that anodal tDCS modulates pain perception by shifts of the resting membrane potential and consequent alteration of the corticospinal excitability at the stimulation site. tDCS was demonstrated to improve pain symptoms in patients with different types of chronic pain[6] but with conflicting results. While in painful diabetic neuropathy anodal tDCS produces pain relief, in chronic lower back pain and postoperative pain the results were conflicting, while cathodal nor anodal tDCS was ineffective[7–9], recently a combination of tDCS and peripheral electrical stimulation has been shown to improve low back pain symptoms more effectively than either applied alone or a sham control[10]. In chronic headaches, anodal tDCS was demonstrated to be an effective non-invasive treatment, but for classical trigeminal neuralgia (TN) and orofacial pain data is rare[11].

TN is a rare facial pain disorder with a prevalence of 0.1 – 0.2/1000 that leads to paroxysms of short lasting but very severe pain[12]. In most cases the third and second branch of the trigeminal nerve are affected[13]. Pain can occur spontaneously but also triggered attacks due to e.g. eating, talking or brushing the teeth occur frequently[13]. Between the attacks the patient is usually asymptomatic, but a constant dull background pain in the affected trigeminal facial area may persist[13], which has been suggested to be a sign of central sensitization and chronification of pain[14]. Carbamazepine is currently the drug of first choice in the treatment of TN. It is effective in 70-80% of patients but often associated with severe adverse effects such as drowsiness, confusion, nausea and ataxia, which may require discontinuation of medication[15]. TN often begins with higher age, which lowers the tolerability of side effects and interactions due to medication[16]. Surgical interventions, like the microvascular decompression, stereotactic radiotherapy or the percutaneous may not be suitable for all patients and waiting for the procedure can be agonizing. Therefore, different non-invasive treatment options are indispensable. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of anodal tDCS of the motor cortex in the treatment of TN with and without concomitant permanent pain using a randomized, cross-over design. Pain evoked potentials and the nociceptive blink reflex were used as objective measure of the tDCS effect on human trigeminal pain processing.

Methods

Patients

Seventeen patients were enrolled in the study. Five patients finished anodal stimulation and discontinued the study without sham stimulation, one patient discontinued after sham stimulation without anodal treatment and one patient did not stimulate at all as recorded in the stimulator. Three of the patients that were only treated anodal, reported the application of the stimulation as too difficult, one patient reported an increase of attacks and one patient reported no further interest in the stimulation. In total, 10 patients completed the study with a mean age of 63 years (range: 49–82 years; 4 patients started with anodal treatment, 6 with sham treatment; see Table 1). Inclusion criteria were: classical TN with or without concomitant permanent pain according to the beta-version of the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3 beta, chapter 13.1.1). Six patients suffered from classical TN with concomitant permanent pain (ICHD-3 beta chapter 13.1.1.2), four were included in the final analysis. Patients required a stable medication with no change of dosage within the last six months. All patients had additional medication with different combinations of antiepileptic drugs (Table 1). MRI prior to study begin was performed to detect a nerve-vessel conflict and symptomatic causes for TN. None of the investigated patients had an invasive procedure prior to study inclusion (i.e., percutaneous ganglion gasseri procedures, microvascular decompression, gamma knife surgery). Patients with other chronic pain disorders or disorders of the nervous system were excluded. One patient additionally suffered from migraine. The local ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen approved the experimental protocol, all study participants provided written informed consent.

Pain assessment

Pain was measured using a verbal rating scale (VRS) as self-evaluation ranges from 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximal pain). VRS and attack frequency were assessed as an averaged value per day for one month before, during and after tDCS using an individual patient diary. The average value of three days prior to tDCS was used for baseline and the average of the last three days after day 14 (=post-stimulation) was used for further analysis. We used this to exclude a failure by single days with higher pain raitings which may occur in TN. Furthermore, participants documented the frequency of pain attacks per day in the same fashion and analysis was also based on the average of the last three days prior to assessment day (e.g., baseline and post-stimulation).

Transcranial direct current stimulation

TDCS was delivered by a battery-driven constant current stimulator (Neuronica, Torino, Italy) with a maximum output of 5 mA using a pair of surface rubber electrodes in a NaCl-solution soaked synthetic sponge with an extension of 4×4 cm over the primary motor cortex (M1) and 5×10 cm above the contralateral orbit. The use of non-metallic rubber electrodes avoids electrochemical polarization (Figure 1). The electrode for tDCS is large, so that the stimulation encompassed a broad area of the motor cortex (upper limb and face). Patients received either anodal or sham stimulation, starting with either one in a double blind randomized fashion and were aware of the study design including sham stimulation. First, the hand area over the contralateral hemisphere to pain was determined by a single pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). For anodal stimulation, the active electrode was placed over the hand representation field of the motor cortex and the reference was placed above the contralateral eyebrow according to the international 10–20 system for EEG electrode placement. The sham stimulation was administered by fixing the electrodes at the same positions and switching on the current for less than five seconds at a current strength below 500 μA in order to cause a slightly itching or tingling sensation and simulate the real current stimulation. Patients were asked if they feel the tingling. Thus, the patients felt the initial current sensation, but received no current for the rest of the stimulation period. With this procedure, patients cannot distinguish between verum and sham stimulation. The current was applied for 20 minutes at an intensity of 1.0 mA, according to current safety recommendations[17]. The maximum current density was 62.5 μA/cm2 over M1 and 12 μA/cm2 at the reference electrode. After the first stimulation, participants and at least one relative were instructed for the correct application of tDCS and were able to stimulate at home. Subsequently the patients applied the stimulation daily by themselves and were instructed to record daily, whether or not any potential side effects occurred in their diary. To ensure the correct application of tDCS, the stimulator records the correct current application in an electronic protocol. In cases of malfunctions or handling problems, the patients had the possibility to call the study team, which has not been used. Stimulation was performed for 14 days, 20 minutes per day. Following a cross-over study design participants were administered sham stimulation or anodal stimulation in a randomized order with an interval of at least one month after the first stimulation to avoid carry over effects.

Electrophysiological settings

Two planar concentric electrodes (inomed Medizintechnik GmbH, Emmendingen, Germany,http://www.inomed.com) were attached to the skin 10 mm above the entry zone of the supraorbital nerve. The outer rim of the first electrode was placed 1 cm from the forehead midline, the second electrode approximately 2 cm apart and lateral. Left side and right side were stimulated 15 times per session in each patient (triple pulse, monopolar square wave, duration 0.5 ms, pulse interval 5 ms, interstimulus interval: 12 to 18 seconds, pseudo-randomized). Perception and pain thresholds were determined on the forehead with an ascending and descending sequence of 0.2 mA intensity steps. The stimulus intensity was set at 2 times the individual pain threshold. Stimuli were delivered to each side in random order in terms of start site (i.e., left or right side of the forehead). NBR and PREP were recorded simultaneously following trigeminal stimulation of the forehead. The nBR was recorded using surface electrodes placed infraorbitally referenced to the orbital rim. Recording parameters: bandwidth 1 Hz to 1 kHz, sampling rate 2.5 kHz, sweep length 300 ms (1401 plus, Signal, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK). PREP were recorded with electrodes placed at Cz referenced to linked earlobes (A1-A2) according to the international 10–20 system. The first sweep was rejected to avoid contamination by startle response. The remaining 14 sweeps were averaged. For nBR onset latencies, waveforms were rectified and analysed for each sweep separately. A mean value for each session was calculated. Area under the curve was calculated between 27-87 ms. Concerning PREP N2 (negative peak), P2 (positive peak) latencies and peak-to-peak amplitudes were analysed. Intraindividual mean ratios for latencies, amplitudes, and area under the curve were determined in all patients for the symptomatic and non-symptomatic pain side separately. Offline-analysis was performed with a custom-written PC-based software using Matlab (Matlab 7, The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

As of the small sample size non-parametric statistical methods were applied. Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples was used to compare pain intensity (VRS), attack frequency, individual pain threshold, AUC, latency, and amplitude of electrophysiological experiments at baseline and after 14 days tDCS. Correlation analysis was performed investigating the association of electrophysiological response with clinical response to tDCS. All statistics were calculated with SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of significance was set to p <0.05.

Results

All patients tolerated tDCS well without adverse effects. With initiation of tDCS, patients feel a slight itching or tingling, while no motor symptoms were observed or reported during the stimulation. Six patients discontinued the trial prematurely as they did not have their expected treatment response. One patient did not stimulate at all. For characterization of patients see Table 1.

Pain assessment after tDCS

Pain intensity (VRS) difference comparing anodal stimulation effect (post-stimulation minus baseline) with the sham effect (post-stimulation minus baseline) was 29% (p = 0.008; Figure 2). VRS decreased after anodal stimulation from baseline by 18% (±SD 29%, while sham stimulation led to an 11% (±30.8%) increase of VRS (Figure 2, Table 1). Attack frequency was not significantly decreased between sham or anodal stimulation (p = 0.123); Figure 1). One patient was completely pain free after anodal stimulation.

Analgesic efficacy of anodal transcranial direct currents stimulation (tDCS). tDCS significantly decreases mean pain intensity on the verbal rating scale (VRS) (p < 0.05), while attack frequency (AF) is not significantly different compared to control conditions. Changes of values are expressed as Δ compared to mean values under control conditions in box plots.

In TN patients with purely paroxysmal pain tDCS decreases VRS by 24.2% after anodal stimulation and increased by 28% after sham stimulation (p = 0.032). Attack frequency decreases in either anodal or sham group not significantly (41.9 vs 56%; p = 0.148).

TN patients with concomitant persistent pain alone did not respond to tDCS at all (0%) change after anodal stimulation and 14.8% (SD ± 13.8%) after sham stimulation (p = 1.0). Attack frequency was not significantly different (p = 391; Table 2).

PREP and nBR after tDCS

Trigeminal PREPs and nBR were elicited using similar current intensities without significant differences between patients after both, anodal tDCS and sham stimulation, compared to baseline conditions (Figure 3, Table 3). No relevant changes were apparent in nBR R2 latencies and nBR areas under the curve (Figure 3B, Table 3) so that brainstem trigeminal nociceptive processing is not equally affected by tDCS. There were no relevant differences in PREP or nBR between patients with and without concomitant permanent pain or in comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic side. No correlation of PREP or nBR with VRS or attack frequency was found.

Effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on (A) pain-related evoked potentials (PREPs) and (B) nociceptive blink reflex (nBR). Anodal tDCS results in decreased trigeminal peak-to-peak amplitudes and increased N2 latencies compared to baseline. Trigeminal N2 latencies and area under the curve are not significantly different between anodal tDCS and sham stimulation. Grey lines mark single patients, red lines mark mean values.

Discussion

Our results provide evidence that anodal tDCS of the primary motor cortex (M1 area) contralateral to the symptomatic side moderately ameliorates pain in patients with classical TN with purely paroxysmal pain by modulation of trigeminal nociceptive processing. Patients with concomitant permanent pain do not seem to benefit from tDCS[18–21].

To our knowledge, the effects of anodal tDCS on facial pain were investigated in only one study, including 22 patients with different pain syndromes. Three patients suffered from TN and one patient from persistent idiopathic facial pain. However, the efficacy of pain relief in these patients was not analyzed separately, so that a clear effect on TN specifically cannot be derived from these data[6]. Comparing our data with previous studies that used anodal tDCS for the treatment of pain we found a slightly attenuated analgesic effect with a reduction of VRS by 29% compared to a maximum of 50% that was previously described[6, 22]. This increases to 38% when we remove those patients with concomitant permanent pain from the analysis that did not respond to tDCS, but remains in a rather moderate nevertheless realistic range.

TDCS has been used more and more frequently over the past decade as a non-invasive neuromodulation for targeted alteration of cortical excitability for the treatment of different diseases like depression, reorganization after stroke and pain[23–25]. Effects of tDCS depend on several factors including polarity, stimulated area, intensity and duration. The improvement of pain by anodal tDCS was convincingly demonstrated in several studies[6, 22, 11]. Although the exact mechanism behind the efficacy of tDCS on chronic pain is not known, probable mechanisms are the changes of the resting membrane potential under the active electrode and remote effects in other parts of the pain processing network by functional interconnections between motor-cortex driven inhibition of the somatosensory cortex and changes in thalamic activity. In addition, long-term effects are mediated by modulation of i.e. NMDA and nicotinic receptor activity inducing neuroplastic effects[5]. Furthermore, anodal stimulation was shown to induce an increase of endogenous opioid release[26] which was located in parts of the pain processing network after tDCS over the M1 area.

When pain becomes chronic tDCS modulation might be less prominent[14]. This could explain why TN patients with concomitant permanent pain in our study did not respond. Moreover, it was demonstrated that the analgesic effect of tDCS critically depends on the electrode montage. An optimized cortical target supported by high-resolution computational models including CNS structures of the pain processing network markedly improved tDCS efficacy[27] and utilization of smaller, more focal electrodes led to significant pain reduction in fibromyalgia[28]. Differences in electrode montage might explain some of the contradictory results in different studies.

Central facilitation and hyperexcitability of the trigeminal system was recently demonstrated in TN patients using PREP and nBR[19]. Other reports presented an increased fMRI activation and grey matter changes of cortical pain processing networks to further support an involvement of cortical structures[29, 21]. It was shown that tDCS affects human trigeminal pain processing[30]. Recordings of PREP and nBR before and after anodal tDCS resulted in decreased peak-to-peak amplitudes of PREP suggesting an inhibition of trigeminal pain processing which provides evidence that tDCS is a potential therapeutic option in disorders associated with central facilitation. Anodal tDCS modulates pain processing by inhibition of corticothalamic epicritic and nociceptive sensations at the thalamic nuclei[31] and induces changes in brain synchronization in the stimulated area[32]. Moreover, changes were observed in the anterior cingulate cortex which was suggested to be the generator of PREP in humans[33]. These observations reconfirm tDCS to interfere with TN pathophysiology. The results in the anodal group of our study showed an inhibition of trigeminal pain processing after tDCS in PREP similar to what was observed previously in healthy patients[30] even though these changes did not reach the level of significance due to the small sample size.

Supposing that the intensity of TN pain depends on combined peripheral and central mechanisms, the attack frequency may be more dependent on peripheral mechanisms e.g. nerve-vessel contact as trigger and, therefore, may not be equally well modulated by cortical stimulation. This might explain why the tDCS effect on attack frequency was insignificant.

The limitations of this study have to be considered. The relatively high drop out rate with more female than male patients shows that self-tDCS application at home may pose a huge problem for the mostly elderly TN target population, even though side effects were not reported and tolerability of participating patients was high. The stimulation with tDCS appears to be more difficult for the patients than previously suspected and probably requires a considerable education effort before it can be used sufficiently. Stimulation frequency (every day for 14 days) may not be optimal as a shorter duration may be just as effective or longer duration may be even more effective, but that will have to be tested in future studies. Due to the enormous interindividual variability in regard to tDCS treatment response it might be difficult to find the optimal stimulation parameters that suits all patients.

All patients received therapy with different anti-epileptic medications that may have influenced clinical and electrophysiological data. We tried to minimize this impact by requiring a stable dose for six months prior to study inclusion. Carry-over effects due to the cross over trial design must be considered despite the 30-day interval between treatment conditions. There is evidence that patients with a special polymorphism in the BDNF receptor gene showed a pronounced facilitation after anodal and inhibition after cathodal tDCS[34]. This may also have affected our patients, but due to the low patient numbers we did not want to exclude anybody and, therefore, did not control for this. Long term effects of tDCS have to be considered. The duration of tDCS effects depend on several factors including the stimulation protocol, remote effects of other cortical areas and modulation of neuronal receptor activity beside NMDA-R effects. These factors are highly individual and underline the complexity of tDCS effects. It has been shown that brain plasticity depends also on the modulation of nicotinic receptors, BDNF polymorphisms and sex hormonal variations[35, 36]. Therefore, the differences in efficacy of the acute and long-term effects of tDCS may depend on factors that are hard to control in studies with rare diseases and low patient numbers.

Conclusion

In summary, tDCS is a promising non-invasive treatment option for trigeminal neuralgia without side effects in patients without satisfying response to medical treatment. Nonetheless, larger studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of action of tDCS in trigeminal pain and to reconfirm its efficacy in TN.

References

Nitsche MA, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, Priori A, Lang N, Antal A, Paulus W, Hummel F, Boggio PS, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A: Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimul 2008, 1(3):206–223. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004

Bindman LJ, Lippold OC, Redfearn JW: The action of brief polarizing currents on the cerebral cortex of the rat (1) during current flow and (2) in the production of long-lasting after-effects. J Physiol 1964, 172: 369–382.

Creutzfeldt OD, Fromm GH, Kapp H: Influence of transcortical d-c currents on cortical neuronal activity. Exp Neurol 1962, 5: 436–452. 10.1016/0014-4886(62)90056-0

Liebetanz D, Nitsche MA, Tergau F, Paulus W: Pharmacological approach to the mechanisms of transcranial DC-stimulation-induced after-effects of human motor cortex excitability. Brain 2002, 125(Pt 10):2238–2247.

Lang N, Siebner HR, Ward NS, Lee L, Nitsche MA, Paulus W, Rothwell JC, Lemon RN, Frackowiak RS: How does transcranial DC stimulation of the primary motor cortex alter regional neuronal activity in the human brain? Eur J Neurosci 2005, 22(2):495–504. doi:10.1111/j.1460–9568.2005.04233.x 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04233.x

Antal A, Terney D, Kuhnl S, Paulus W: Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the motor cortex ameliorates chronic pain and reduces short intracortical inhibition. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010, 39(5):890–903. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.023 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.023

Kim YJ, Ku J, Kim HJ, Im DJ, Lee HS, Han KA, Kang YJ: Randomized, sham controlled trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for painful diabetic polyneuropathy. Ann Rehabil Med 2013, 37(6):766–776. doi:10.5535/arm.2013.37.6.766 10.5535/arm.2013.37.6.766

O’Connell NE, Cossar J, Marston L, Wand BM, Bunce D, De Souza LH, Maskill DW, Sharp A, Moseley GL: Transcranial direct current stimulation of the motor cortex in the treatment of chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized, double-blind exploratory study. Clin J Pain 2013, 29(1):26–34. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318247ec09 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318247ec09

Dubois PE, Ossemann M, de Fays K, De Bue P, Gourdin M, Jamart J, Vandermeeren Y: Postoperative analgesic effect of transcranial direct current stimulation in lumbar spine surgery: a randomized control trial. Clin J Pain 2013, 29(8):696–701. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31826fb302 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31826fb302

Schabrun SM, Jones E, Elgueta Cancino EL, Hodges PW: Targeting chronic recurrent low back pain from the top-down and the bottom-up: a combined transcranial direct current stimulation and peripheral electrical stimulation intervention. Brain Stimul 2014, 7(3):451–459. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2014.01.058 10.1016/j.brs.2014.01.058

Pinchuk D, Pinchuk O, Sirbiladze K, Shugar O: Clinical effectiveness of primary and secondary headache treatment by transcranial direct current stimulation. Front Neurol 2013, 4: 25. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00025

Manzoni GC, Torelli P: Epidemiology of typical and atypical craniofacial neuralgias. Neurol Sci 2005, 26(Suppl 2):s65-s67. doi:10.1007/s10072–005–0410–0

Maarbjerg S, Gozalov A, Olesen J, Bendtsen L: Trigeminal neuralgia - a prospective systematic study of clinical characteristics in 158 patients. Headache 2014. doi:10.1111/head.12441

Hu WH, Zhang K, Zhang JG: Atypical trigeminal neuralgia: a consequence of central sensitization? Med Hypotheses 2010, 75(1):65–66. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2010.01.028 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.01.028

Graham JG, Zilkha KJ: Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with carbamazepine: a follow-up study. Br Med J 1966, 1(5481):210–211. 10.1136/bmj.1.5481.210

Pascual J, Berciano J: Experience in the diagnosis of headaches that start in elderly people. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994, 57(10):1255–1257. 10.1136/jnnp.57.10.1255

Liebetanz D, Koch R, Mayenfels S, Konig F, Paulus W, Nitsche MA: Safety limits of cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation in rats. Clin Neurophysiol 2009, 120(6):1161–1167. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2009.01.022 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.01.022

Szapiro J Jr, Sindou M, Szapiro J: Prognostic factors in microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 1985, 17(6):920–929. 10.1227/00006123-198512000-00009

Obermann M, Yoon MS, Sensen K, Maschke M, Diener HC, Katsarava Z: Efficacy of pregabalin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia 2008, 28(2):174–181. doi:10.1111/j.1468–2982.2007.01483.x

Sandell T, Eide PK: Effect of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia patients with or without constant pain. Neurosurgery 2008, 63(1):93–99. discussion 99–100. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000335075.16858.EF 10.1227/01.NEU.0000335075.16858.EF

Obermann M, Rodriguez-Raecke R, Naegel S, Holle D, Mueller D, Yoon MS, Theysohn N, Blex S, Diener HC, Katsarava Z: Gray matter volume reduction reflects chronic pain in trigeminal neuralgia. NeuroImage 2013, 74: 352–358. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.029

Fregni F, Boggio PS, Lima MC, Ferreira MJ, Wagner T, Rigonatti SP, Castro AW, Souza DR, Riberto M, Freedman SD, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A: A sham-controlled, phase II trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of central pain in traumatic spinal cord injury. Pain 2006, 122(1–2):197–209. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.023

Fregni F, Gimenes R, Valle AC, Ferreira MJ, Rocha RR, Natalle L, Bravo R, Rigonatti SP, Freedman SD, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, Boggio PS: A randomized, sham-controlled, proof of principle study of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2006, 54(12):3988–3998. doi:10.1002/art.22195 10.1002/art.22195

Nitsche MA, Boggio PS, Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A: Treatment of depression with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): a review. Exp Neurol 2009, 219(1):14–19. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.038 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.038

Schlaug G, Renga V: Transcranial direct current stimulation: a noninvasive tool to facilitate stroke recovery. Expert Rev Med Devices 2008, 5(6):759–768. doi:10.1586/17434440.5.6.759 10.1586/17434440.5.6.759

DosSantos MF, Love TM, Martikainen IK, Nascimento TD, Fregni F, Cummiford C, Deboer MD, Zubieta JK, Dasilva AF: Immediate effects of tDCS on the mu-opioid system of a chronic pain patient. Front Psychiatry 2012, 3: 93. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00093

Mendonca ME, Santana MB, Baptista AF, Datta A, Bikson M, Fregni F, Araujo CP: Transcranial DC stimulation in fibromyalgia: optimized cortical target supported by high-resolution computational models. J Pain 2011, 12(5):610–617. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.015 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.015

Villamar MF, Wivatvongvana P, Patumanond J, Bikson M, Truong DQ, Datta A, Fregni F: Focal modulation of the primary motor cortex in fibromyalgia using 4x1-ring high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS): immediate and delayed analgesic effects of cathodal and anodal stimulation. J Pain 2013, 14(4):371–383. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.12.007 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.12.007

Borsook D, Moulton EA, Pendse G, Morris S, Cole SH, Aiello-Lammens M, Scrivani S, Becerra LR: Comparison of evoked vs. spontaneous tics in a patient with trigeminal neuralgia (tic doloureux). Mol Pain 2007, 3: 34. doi:10.1186/1744–8069–3-34 10.1186/1744-8069-3-34

Hansen N, Obermann M, Poitz F, Holle D, Diener HC, Antal A, Paulus W, Katsarava Z: Modulation of human trigeminal and extracranial nociceptive processing by transcranial direct current stimulation of the motor cortex. Cephalalgia 2011, 31(6):661–670. doi:10.1177/0333102410390394 10.1177/0333102410390394

Ragert P, Vandermeeren Y, Camus M, Cohen LG: Improvement of spatial tactile acuity by transcranial direct current stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 2008, 119(4):805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.12.001 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.12.001

Polania R, Nitsche MA, Paulus W: Modulating functional connectivity patterns and topological functional organization of the human brain with transcranial direct current stimulation. Hum Brain Mapp 2011, 32(8):1236–1249. doi:10.1002/hbm.21104 10.1002/hbm.21104

Bromm B: The involvement of the posterior cingulate gyrus in phasic pain processing of humans. Neurosci Lett 2004, 361(1–3):245–249. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2004.01.018

Antal A, Chaieb L, Moliadze V, Monte-Silva K, Poreisz C, Thirugnanasambandam N, Nitsche MA, Shoukier M, Ludwig H, Paulus W: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene polymorphisms shape cortical plasticity in humans. Brain Stimul 2010, 3(4):230–237. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2009.12.003 10.1016/j.brs.2009.12.003

de Tommaso M, Invitto S, Ricci K, Lucchese V, Delussi M, Quattromini P, Bettocchi S, Pinto V, Lancioni G, Livrea P, Cicinelli E: Effects of anodal TDCS stimulation of left parietal cortex on visual spatial attention tasks in men and women across menstrual cycle. Neurosci Lett 2014, 574: 21–25. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.014

Batsikadze G, Paulus W, Grundey J, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA: Effect of the nicotinic alpha4beta2-receptor partial agonist varenicline on non-invasive brain stimulation-induced neuroplasticity in the human motor cortex. Cereb Cortex 2014. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhu126

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Tim Hagenacker has received research support from Astellas and CSL Behring.

Vera Bude, Steffen Naegel have nothing to disclose.

Dagny Holle has received research support from Grünental and Allergan.

Mark Obermann has received scientific support and/or honoraria from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme, Pfizer, Teva. He received research grants from Allergan, Electrocore, and the German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF).

Hans-Christoph Diener has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or lectures from Addex Pharma, Allergan, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bayer Vital, Berlin Chemie, Coherex Medical, CoLucid, Böhringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, La Roche, 3M Medica , Minster, MSD, Novartis, Johnson & Johnson, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Schaper and Brümmer, SanofiAventis, and Weber & Weber; received research support from Allergan, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Galaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen-Cilag, and Pfizer. Headache research at the Department of Neurology in Essen is supported by the German Research Council (DFG), the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and the European Union.

Authors’ contributions

MO and ZK conceptualized the experimental design. MO and TH organized the study. TH and VB acquired the data. TH, VB, SN and DH were responsible for the clinical supervision of the test persons. TH, DH, HD and MO analyzed the data. MO conducted the statistical analysis. TH wrote the first draft of the manuscript and interpreted the findings. All authors gave input to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hagenacker, T., Bude, V., Naegel, S. et al. Patient-conducted anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of the motor cortex alleviates pain in trigeminal neuralgia. J Headache Pain 15, 78 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-78

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-78