Abstract

In this paper, we investigate dynamic optimization problems featuring both stochastic control and optimal stopping in a finite time horizon. The paper aims to develop new methodologies, which are significantly different from those of mixed dynamic optimal control and stopping problems in the existing literature. We formulate our model to a free boundary problem of a fully nonlinear equation. Furthermore, by means of a dual transformation for the above problem, we convert the above problem to a new free boundary problem of a linear equation. Finally, we apply the theoretical results to some challenging, yet practically relevant and important, risk-sensitive problems in wealth management to obtain the properties of the optimal strategy and the right time to achieve a certain level over a finite time investment horizon.

MSC:35R35, 91B28, 93E20.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Optimal stopping problems, a variant of optimization problems allowing investors freely to stop before or at the maturity in order to maximize their profits, have been implemented in practice and given rise to investigation in academic areas such as science, engineering, economics and, particularly, finance. For instance, pricing American-style derivatives is a conventional optimal stopping time problem where the stopping time is adapted to the information generated over time. The underlying dynamic system is usually described by stochastic differential equations (SDEs). The research on optimal stopping, consequently, has mainly focused on the underlying dynamic system itself. In the field of financial investment, however, an investor frequently runs into investment decisions where investors stop investing in risky assets so as to maximize their expected utilities with respect to their wealth over a finite time investment horizon. These optimal stopping problems depend on the underlying dynamic systems as well as investors’ optimization decisions (controls). This naturally results in a mixed optimal control and stopping problem, and Ceci and Bassan [1] is one of the typical works along this line of research. In the general formulation of such models, the control is mixed, composed of a control and a stopping time. The theory has also been studied in Bensoussan and Lions [2], Elliott and Kopp [3], Yong and Zhou [4] and Fleming and Soner [5], and applied in finance in Dayanik and Karatzas [6], Henderson and Hobson [7], Li and Zhou [8], Li and Wu [9, 10] and Shiryaev, Xu and Zhou [11].

In the finance field, finding an optimal stopping time point has been extensively studied for pricing American-style options, which allow option holders to exercise the options before or at the maturity. Typical examples that are applicable include, but are not limited to, those presented in Chang, Pang and Yong [12], Dayanik and Karatzas [6] and Rüschendorf and Urusov [13]. In the mathematical finance literature, choosing an optimal stopping time point is often related to a free boundary problem for a class of diffusions (see Fleming and Soner [5] and Peskir and Shiryaev [14]). In many applied areas, especially in more extensive investment problems, however, one often encounters more general controlled diffusion processes. In real financial markets, the situation is even more complicated when investors expect to choose as little time as possible to stop portfolio selection over a given investment horizon so as to maximize their profits (see Samuelson [15], Karatzas and Kou [16], Karatzas and Sudderth [17], Karatzas and Wang [18], Karatzas and Ocone [19], Ceci and Bassan [1], Henderson [20], Li and Zhou [8] and Li and Wu [9, 10]).

The initial motivation of this paper comes from our recent studies on choosing an optimal point at which an investor stops investing and/or sells all his risky assets (see Choi, Koo and Kwak [21] and Henderson and Hobson [7]). The objective is to find an optimization process and stopping time so as to meet certain investment criteria, such as, the maximum of an expected utility value before or at the maturity. This is a typical problem in the area of financial investment. However, there are fundamental difficulties in handling such optimization problems. Firstly, our investment problems, which are different from the classical American-style options, involve optimization process over the entire time horizon. Secondly, they involve the portfolio in the drift and volatility terms so that the problem of multi-dimensional financial assets are more realistic than those addressed in finance literature (see Capenter [22]). Therefore, it is difficult to solve these problems either analytically or numerically using current methods developed in the framework of studying American-style options. In our model, the corresponding HJB equation of the problem is formulated into a variational inequality of a fully nonlinear equation. We make a dual transformation for the problem to obtain a new free boundary problem with a linear equation. Tackling this new free boundary problem, we establish the properties of the free boundary and optimal strategy for the original problem.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the mathematical formulation of the model is presented, and the corresponding HJB equation is posed. In Section 3, a dual transformation converts the free boundary problem of a fully nonlinear PDE to a new free boundary problem of a linear equation but with the complicated constraint (3.16). In Section 4 we simplify the constraint condition in (3.16) to obtain a new free boundary problem with a simple condition (4.4). Moreover, we show that the solution of problem (4.5) must be the solution of problem (3.15). Section 5 is devoted to the study of the free boundary of problem (4.5). In Section 6, we go back to the original problem (2.6) to show that its free boundary is decreasing and differentiable. Moreover, we present its financial meanings. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2 Model formulation

2.1 The manager’s problem

The manager operates in a complete, arbitrage-free, continuous-time financial market consisting of a riskless asset with instantaneous interest rate r and n risky assets. The risky asset prices are governed by the stochastic differential equations

where the interest rate r, the excess appreciation rates , and the volatility vectors are constants, W is a standard n-dimensional Brownian motion. In addition, the covariance matrix is strongly nondegenerate.

A trading strategy for the manager is an n-dimensional process whose i th component, where is the holding amount of the i th risky asset in the portfolio at time t. An admissible trading strategy must be progressively measurable with respect to such that . Note that , where is the amount invested in the money market. The value of the wealth evolves according to

In addition, short-selling is allowed.

The manager controls assets with initial value x. The manager’s dynamic problem is to choose an admissible trading strategy and a stopping time τ to maximize his expected utility of the exercise wealth:

where is the interest and K is a positive constant (e.g., a fixed salary),

is the utility function.

2.2 HJB equation

Applying the dynamic programming principle, we get the following Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman (HJB) equation:

Suppose that is strictly increasing and strictly concave, i.e., , . Note that the gradient of with respect to π

then

Thus (2.4) becomes

where . Now we find a condition under which the free boundary exists. A simple calculation shows

It follows that

Eliminating yields

i.e.,

If

then (2.7) holds for any , the solution to problem (2.6) is .

If

then (2.7) is impossible for any . Therefore, in this case, the solution to problem (2.6) satisfies

We summarize the above results in the following theorem.

Theorem 2.1 In the following cases, problem (2.6) has a trivial solution.

-

(1)

If (2.8) holds, the solution to problem (2.6) is .

-

(2)

If (2.9) holds, the solution to problem (2.10) is the solution to problem (2.6) as well.

Recalling (2.8) and (2.9), in the following we always assume that

In the case of (2.11), there exists a free boundary.

3 Dual transformation

Define a dual transformation of (see Pham [23])

If is strictly decreasing, which is equivalent to the strict concavity of (we will show this fact in the end of Section 5), then the maximum in (3.1) will be attained at just one point

which is the unique solution of

Using the coordinate transformation (3.2) yields

Differentiating with respect to y and t, we get

Substituting (3.5) into (3.4), we have

By the transformation (3.2) and (3.3)-(3.8), the HJB equation in (2.6) becomes

Now we derive the terminal condition for . Note that

so , i.e., . It follows that

and by (3.8), we have

Next, we determine the upper bound for y. In fact, in the neighborhood of , so the upper bound is

In addition, we need to determine the value . By (3.8), we also have

Combining (3.9) and (3.12)-(3.14), we obtain

In (3.15), the equation is a linear parabolic equation, but the constraint condition

is very complicated. In the following section, we simplify this condition.

Remark The equation in (3.15) is degenerate on the boundary . According to Fichera’s theorem (see Oleĭnik and Radkević [24]), we must not put the boundary condition on .

4 Simplifying the complicated constraint condition

Note that in the domain , we have

By the y coordinate,

Deriving from the first equality in (4.2) yields

and then substituting (4.3) into (3.16), we have

This is the simplified constraint condition. We assume that satisfies

where

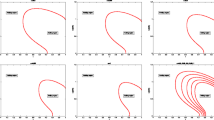

Moreover, we split the domain into two parts; denote (see Figure 1)

Theorem 4.1 The solution to problem (4.5) is the solution to problem (3.15) as well.

In order to prove this theorem, we first show the following two lemmas.

Lemma 4.1 For any , we have

Proof Equation (4.8) follows from the definition (4.6) directly. Also, in

Differentiating (4.10) to y yields

Note that

where is the boundary of .

Denote , we further show that w is a supersolution to problem (4.11)-(4.13) by

and

So w is a supersolution of (4.11)-(4.13). This means that (4.9) holds. □

Lemma 4.2 The function

is increasing with respect to if .

Proof Define a function

Then

if . □

Proof of Theorem 4.1 Note that, from (4.5),

Rewrite (4.15) as

Applying (4.8) to (4.16), we have

On the other hand, from (4.5), in

We rewrite (4.19) as

Applying (4.9) and Lemma 4.2, we get

□

5 The free boundary of problem (4.5)

Denote

Theorem 5.1 Problem (4.5) has a unique solution , and

where .

Proof According to the existence and uniqueness of , the solution for system (4.5) can be proved by a standard penalty method (see Friedman [25]). Here, we omit the details. The first inequality in (5.1) follows from (4.5) directly, and now we prove the second inequality in (5.1). Denote

where to be determined later on. We first show that is a supersolution to problem (4.5). In fact,

if

So, is a supersolution to problem (4.5). Hence, the second inequality in (5.1) holds.

In addition, inequality (5.2) follows from (4.8) and (4.9). In order to prove (5.3), we define

From (4.5), we know that satisfies

Applying the comparison principle to variational inequalities (4.5) and (5.4) with respect to terminal values (see Friedman [26]), we obtain

Thus and (5.3) holds. □

Based on (5.2), we define the free boundary

Theorem 5.2 The free boundary function is monotonic decreasing (Figure 2) with

Moreover, .

Proof First, from (5.3), is monotonic decreasing. Denote

In ,

so

Hence,

In order to prove (5.5), we suppose

then it is not hard to get

which is a contradiction to (5.3). Therefore, the desired result (5.5) holds.

Finally, the proof of is similar to the result in Friedman [25]. Here, we omit the details. □

Theorem 5.3 For any , we have

Proof If , then . Thus,

If , then

Differentiating (5.8) with respect to y twice yields

Note that

Applying the minimum principle, we obtain

□

Remark From (3.6), we have , which means V is strict concave to x.

6 The free boundary of original problem (2.6)

Recalling on the free boundary

From the dual transformation (3.2) and (3.5), we know

Denote the free boundary of (2.6) by . Applying (6.2) and (6.3) yields

Moreover,

Thus, we have following theorem.

Theorem 6.1 The free boundary of problem (2.6) is monotonic increasing (Figure 3) and is determined by (6.6). Moreover, .

Financial meanings At time t, the manager should continue to invest according to (2.5) if , while the investor should stop investment if .

7 Concluding remarks

We explore a class of optimal investment problems mixed with optimal stopping in the financial investment. The corresponding HJB equation, a free boundary problem of a fully nonlinear equation, is posed. By means of a dual transformation, we obtain a new free boundary problem with a linear equation under a complicated constraint condition. The key step is to simplify this complicated constraint condition. In this way we study the properties of the free boundary and optimal strategy for investors.

Remark on constant K (salary) If K is a function of time t, , the unique difficulty is the proof of (5.3). If is decreasing, then (5.3) is still right and all results hold as well. In general case if is not decreasing, then the free boundary may be not monotonic. We will consider this problem in the future.

References

Ceci C, Bassan B: Mixed optimal stopping and stochastic control problems with semicontinuous final reward for diffusion processes. Stoch. Stoch. Rep. 2004, 76: 323–337. 10.1080/10451120410001728436

Bensoussan A, Lions JL: Impulse Control and Quasi-Variational Inequalities. Gauthier-Villars, Paris; 1984.

Elliott RJ, Kopp PE: Mathematics of Financial Markets. Springer, New York; 1999.

Yong J, Zhou XY: Stochastic Controls: Hamiltonian Systems and HJB Equations. Springer, New York; 1999.

Fleming W, Soner H: Controlled Markov Processes and Viscosity Solutions. 2nd edition. Springer, New York; 2006.

Dayanik S, Karatzas I: On the optimal stopping problem for one-dimensional diffusions. Stoch. Process. Appl. 2003, 107: 173–212. 10.1016/S0304-4149(03)00076-0

Henderson V, Hobson D: An explicit solution for an optimal stopping/optimal control problem which models an asset sale. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2008, 18: 1681–1705. 10.1214/07-AAP511

Li X, Zhou XY: Continuous-time mean-variance efficiency: the 80% rule. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2006, 16: 1751–1763. 10.1214/105051606000000349

Li X, Wu ZY: Reputation entrenchment or risk minimization? Early stop and investor-manager agency conflict in fund management. J. Risk Finance 2008, 9: 125–150. 10.1108/15265940810853904

Li X, Wu ZY: Corporate risk management and investment decisions. J. Risk Finance 2009, 10: 155–168. 10.1108/15265940910938233

Shiryaev A, Xu ZQ, Zhou XY: Thou shalt buy and hold. Quant. Finance 2008, 8: 765–776. 10.1080/14697680802563732

Chang MH, Pang T, Yong J: Optimal stopping problem for stochastic differential equations with random coefficients. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2009, 48: 941–971. 10.1137/070705726

Rüschendorf L, Urusov MA: On a class of optimal stopping problems for diffusions with discontinuous coefficients. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2008, 18: 847–878. 10.1214/07-AAP474

Peskir G, Shiryaev A: Optimal Stopping and Free-Boundary Problems. 2nd edition. Birkhäuser, Berlin; 2006.

Samuelson PA: Rational theory of warrant pricing. Ind. Manage. Rev. 1965, 6: 13–31. (With an Appendix by HP McKean: A free boundary problem for the heat equation arising from a problem in mathematical economics.)

Karatzas I, Kou SG: Hedging American contingent claims with constrained portfolios. Finance Stoch. 1998, 2: 215–258. 10.1007/s007800050039

Karatzas I, Sudderth WD: Control and stopping of a diffusion process on an interval. Ann. Appl. Probab. 1999, 9: 188–196.

Karatzas I, Wang H: Utility maximization with discretionary stopping. SIAM J. Control Optim. 2000, 39: 306–329. 10.1137/S0363012998346323

Karatzas I, Ocone D: A leavable bounded-velocity stochastic control problem. Stoch. Process. Appl. 2002, 99: 31–51. 10.1016/S0304-4149(01)00157-0

Henderson V: Valuing the option to invest in an incomplete market. Math. Financ. Econ. 2007, 1: 103–128. 10.1007/s11579-007-0005-z

Choi KJ, Koo HK, Kwak DY: Optimal stopping of active portfolio management. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2004, 5: 93–126.

Capenter JN: Does option compensation increase managerial risk appetite? J. Finance 2000, 50: 2311–2331.

Pham H: Continuous-Time Stochastic Control and Optimization with Financial Applications. Springer, Berlin; 2009.

Oleĭnik OA, Radkević EV: Second Order Equations with Nonnegative Characteristic Form. Plenum, New York; 1973.

Friedman A: Parabolic variational inequalities in one space dimension and smoothness of the free boundary. J. Funct. Anal. 1975, 18: 151–176. 10.1016/0022-1236(75)90022-1

Friedman A: Variational Principles and Free-Boundary Problems. Wiley, New York; 1982.

Acknowledgements

Xiongfei Jian and Fahuai Yi are supported by NNSF of China (No. 11271143, No. 11371155 and No. 11471276), University Special Research Fund for Ph.D. Program of China (20124407110001 and 20114407120008). Xun Li is supported by Research Grants Council of Hong Kong under grants 521610 and 519913. The authors are grateful to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their careful reviews, valuable comments, and remarks to improve this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jian, X., Li, X. & Yi, F. Optimal investment with stopping in finite horizon. J Inequal Appl 2014, 432 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1029-242X-2014-432

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1029-242X-2014-432