Abstract

Background

Hibernation allows animals to survive periods of resource scarcity by reducing their energy expenditure through decreased metabolism. However, hibernators become susceptible to psychrophilic pathogens if they cannot mount an efficient immune response to infection. While Nearctic bats infected with white-nose syndrome (WNS) suffer high mortality, related Palearctic taxa are better able to survive the disease than their Nearctic counterparts. We hypothesised that WNS exerted historical selective pressure in Palearctic bats, resulting in genomic changes that promote infection tolerance.

Results

We investigated partial sequences of 23 genes related to water metabolism and skin structure function in nine Palearctic and Nearctic hibernating bat species and one non-hibernating species for phylogenetic signals of natural selection. Using maximum likelihood analysis, we found that eight genes were under positive selection and we successfully identified amino acid sites under selection in five encoded proteins. Branch site models revealed positive selection in three genes. Hibernating bats exhibit signals for positive selection in genes ensuring tissue regeneration, wound healing and modulation of the immune response.

Conclusion

Our results highlight the importance of skin barrier integrity and healing capacity in hibernating bats. The protective role of skin integrity against both pathophysiology and WNS progression, in synergy with down-regulation of the immune reaction in response to the Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection, improves host survival. Our data also suggest that hibernating bat species have evolved into tolerant hosts by reducing the negative impact of skin infection through a set of adaptations, including those at the genomic level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Emergence of a novel infectious disease or pathogen transmission to a naïve population leads to allele frequency changes in populations experiencing disease outbreaks with high mortality [1, 2]. Carriers of alleles that facilitate less serious disease manifestation have a higher chance of survival, while gene variants causing increased susceptibility to the infection or more severe diseases are more likely to vanish from the population gene pool. Pathogens serve as a selective force in susceptible hosts, directing changes in host population genetic diversity. Alterations in host genetic structure driven by pathogens are detectable in coding DNA sequences as signals for natural selection. While equal rates of both substitution types occur during neutral evolution, a higher rate of non-synonymous substitutions (dN) than synonymous substitutions (dS) is a sign of predominant positive selective pressure (dN/dS > 1) and, conversely, higher rates of synonymous substitutions are a sign of predominant negative selective pressure (dN/dS < 1) [3, 4].

White-nose syndrome (WNS), a fungal infection of hibernating bats, potentially applies strong selection pressure on bat populations in the Nearctic. Since its emergence in 2006, WNS has caused the death of millions of bats across the eastern part of North America [5]. Indeed, WNS has led to the near extirpation of some of the most common hibernating Myotis species due to local declines exceeding 90% per year [6, 7]. In comparison, Palearctic bat species suffering from WNS show greater survival, with no reports of population declines attributable to WNS [8, 9] despite sporadic mortality [10, 11].

The difference in survival rate of infected Nearctic and Palearctic bats is most likely connected to species-specific pathophysiologic impacts during host-pathogen interaction. The infective agent of the disease, the psychrophilic fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, invades deep into living skin layers on the hibernating bat’s nose, ears, limbs and membranes [10,11,12,13,14]. The disease may subsequently have a negative effect on ion and blood gas balance [15, 16], evaporative loss of water [17] and overall hibernation behaviour [18]. Frequent arousals from hibernation in infected, moribund bats [19] may also contribute to loss of energy reserves essential for survival. Following arousal from torpor, the host’s infection response will exacerbate tissue damage by immunopathology [20] and reaction to fungal metabolite accumulation. In particular, riboflavin produced by P. destructans, which hyperaccumulates in skin lesions during hibernation, causes oxidative tissue damage [14] and triggers a cytotoxic immune response when presented to the innate immune system [21].

The recent emergence of WNS in the Nearctic resulting in high mortality rates, and later recognition of the pathogen in the Palearctic with differing disease manifestation, suggests spatio-temporal variation in host-pathogen coevolution [22]. Recent evidence demonstrates that P. destructans infection occurred in Palearctic bats prior to its emergence in the Nearctic [23, 24]. Coupled with current disease tolerance in the Palearctic, historical exposure to the pathogen has given rise to the hypothesis that WNS may have caused mass mortality events in the Palearctic in the past. Martínková et al. [8] speculated that the large fossil deposits of bat species now rare in underground hibernacula may have accumulated due to a WNS epidemic in the Pleistocene. Based on the assumption that Palearctic bats were exposed to the lethal skin infection prior to the Holocene, we hypothesised that Palearctic bat species may have evolved inheritable mechanisms leading to tolerance toward the disease. If so, any alteration in genetic information should be detectable in genes encoding proteins interacting with the pathogen in a manner dependent on infection pathophysiology. Identification of those genes targeted by positive selection should enhance our understanding of disease pathogenesis. Considering the disease’s etiology and close functional connection to acid-base and electrolyte homeostasis and skin layer damage during disease progression, we hypothesise that genes involved in water metabolism and skin function in hibernating bat species are most likely to display signatures of positive selection.

Results

Annotated sequences of 23 genes were retrieved from the NCBI database for species in the Vespertilionidae and Miniopteridae families, namely acad10, acp5, anxa1, aqp3, aqp4, aqp7, aqp9, bcam, ctnnb1, fads1, fgf10, guca2b, has2, hyal2, hyal3, krt8, lrp4, psen2, ptch2, pxn, sncg, tgm1, and tnfsf13 (Additional file 1). We sequenced five genes in seven bat species using PacBio SMRT technology (GenBank Accession Numbers: MH178037-MH178081) and supplemented the datasets from the public database with 71 phased partial coding sequences. In other species (Additional file 2), PacBio sequences were not of sufficient quality to provide at least 10× coverage. In total, we analysed 11 bat species with 1–23 genes available per species, and partial coding sequences of 23 genes available in 3–9 species (Additional file 1).

Using a maximum likelihood framework [25], we estimated the rate ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions ω = dN/dS for the available coding sequences. We used the likelihood ratio test (LRT) to differentiate between nested models of DNA sequence evolution, where twice the difference in model log-likelihoods (2ΔlnL) approximately follows a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of model parameters. Comparison of M0 and M3 nested models of DNA sequence evolution (testing for variability of ω between sites) revealed 13 of the 23 genes to be significant after correction for multiple testing with false discovery rate (FDR) (Table 1). Comparison of M1 to M2 and M7 to M8 model pairs (differentiating between neutral and positive selection) revealed significance in seven genes. Statistically significant support for positive selection (FDR adjusted p < 0.05) was detected in genes encoding annexin A1 (anxa1), tartrate resistant acid phosphatase 5 (acp5), aquaporin 3 (aqp3), the basal cell adhesion molecule (bcam), LDL receptor related protein 4 (lrp4), patched 2 (ptch2) and synuclein gamma (sncg) (Table 1).

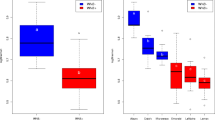

In those genes showing positive selection, we used Bayes empirical Bayes (BEB) to identify specific amino acids encoding sites under significant positive selection (Fig. 1). We identified four sites under positive selection in acp5, seven sites in anxa1 (with one additional site identified from a comparison of the M7 and M8 models), one site in aqp3, one site recognised from both model comparisons and one additional site identified by comparing M7 to M8 in ptch2. All six sites identified in bcam were supported by the M7 to M8 comparison (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Amino acid sites under positive selection in bats. Sites under selection in partial coding sequences of the genes acp5, anxa1, aqp3, bcam and ptch2 were identified phylogenetically for 1–11 individuals of each species using a maximum likelihood framework. The pie charts displayed show the relative frequency of amino acids in each sample. Numbers above the alignment positions refer to the amino acid’s position in the reference (see Table 2). The phylogenetic tree depicts relationships pruned from a previously published multilocus phylogeny [70]. P = bat species distributed in the Palearctic, N = Nearctic, A = Afrotropical

Amino acid sites under positive selection were mapped onto predicted 3D protein structure models of four genes (Fig. 2). In tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP; encoded within the acp5 gene), the selected sites were spread along the protein sequence, while in ANXA1, the selected sites were accumulated in the N-terminal region of the protein (six out of eight sites detected occurred within the range 17–27; Fig. 1). The sole AQP3 site under selection was located within a transmembrane helix, and four out of six sites identified under positive selection in BCAM lay in the 2nd Ig-like C2 type domain (Fig. 2). It was not possible to model the structure of PTCH2, the fifth protein with sites under positive selection. We assume that the two sites under positive selection were both located in the intracellular partition of the protein.

Positively selected sites in bat protein structure. Sites in TRAP, ANXA1, AQP3 and BCAM highlighted in red are under positive selection (estimated by Bayes empirical Bayes) while yellow sites represent iron binding (TRAP) and calcium binding (ANXA1) sites (UniPROT P29288 and P07150, respectively). The models were created by Phyre2 structure prediction software [76], using a reference bat species protein sequence (XP_006104612.1, XP_014396764.1, XP_006758647.1, XP_015416692.1). The PTCH2 model is not included as we were unable to predict a reliable model without a high proportion of ab-initio modelled sites

The branch site test of positive selection compared the two nested models identifying the branch under positive selection (A1 and A). A significant difference between the models indicated positive selection in Eptesicus fuscus (p = 0.001) and E. nilssonii (p = 0.001) in acp5 (Table 3).

We then tested for positive selection on species in a Palearctic monophyletic clade that included Myotis davidii, Myotis emarginatus and Myotis myotis. Three genes under selection were available for the clade (Fig. 1, Additional file 1). Clade model C vs. M2a_rel revealed positive selection in acp5 for the species (p = 0.005), but no significant evidence of selection in anxa1 and aqp3 (p > 0.05).

Discussion

Hibernation is a strategy used by temperate-zone bats to increase survival rate under conditions of constrained energy reserves [26, 27]. Exposure of hibernating individuals to additional stressors, such as pathogen pressure, could result in health-related costs decreasing their ability to overwinter. Mounting an immune response at times of low activity, low body temperature and reduced possibility of regulation and energy uptake is a risky defence mechanism against potential microbial threats as it may contribute to mortality through depletion of fat reserves [19, 28] or overwhelming inflammation [20]. Frequency changes in functionally important single nucleotide polymorphisms in histocompatibility antigens, cytokines and toll-like receptors have been recorded in Myotis lucifugus populations that survived the initial P. destructans epidemic front associated with population decline [2]. Considering the risks associated with immune response investment in hibernators, tolerance of the pathogen at a molecular level is likely to be the best possible approach to infection in hibernation.

WNS pathophysiology is directly connected to the bat’s hibernation ability. Assuming that a) Palearctic bats have been historically exposed to P. destructans [23, 24], b) Nearctic bats represent naïve animals with no historical influence of infection, and c) Afrotropic bats remain healthy as they live in an environment too warm for pathogen growth [29], it should be possible to detect selective changes in the bat genome testifying to the consequences to infection-related mortality, this serving as a selective pressure favouring beneficial mutations over the ancestral genetic sequence.

Infection by P. destructans is dependent on low temperatures as the fungus is unable to grow at temperatures greater than 20 °C [29]. At environmental temperatures prevalent in hibernacula, the fungus invades the host’s skin from the epidermis to the deeper skin layers [20, 30, 31]. An ability to protect the skin from lesions and functional disruption is critical to the bat’s survival, and even more so as regards the skin forming the wing (considered the bat’s largest organ). Of the genes signalling positive selection, many are involved in maintaining skin homeostasis and promoting wound healing (Table 1, Fig. 3). While proving a direct causal link between selection on particular genes (Table 1) and historical P. destructans exposure is impossible without experimental manipulation, the molecular function of genes under selection may be interpreted in relation to a skin infection.

Molecular mechanistic model of white-nose syndrome (WNS) tolerance in bats. During hibernation, a bat’s body temperature, metabolic rate and immune system are lowered for up to six months, only increasing for periods lasting up to several hours during periodic arousal from torpor. Bat hibernation provides suitable conditions for Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection and development of the fungal disease WNS. The fungus initially grows on the skin’s surface and progresses toward invasive infection, whereupon it deposits large amounts of vitamin B2 into skin lesions, leading to skin necrosis. In the most severe cases, either large areas of skin become necrotic or the immune system’s response to massive infection overwhelms the animal upon arousal. Molecular mechanisms supporting WNS tolerance are likely to include strengthening of skin integrity maintenance and enhancement of wound healing. Surprisingly, there may also be negative modulation of the immune response, which could otherwise deplete the bat’s energy reserves or cause death through immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome [20]

Sites under positive selection in the Patched 2 protein (PTCH2) were located in the protein intracellular partition (Fig. 1). PTCH2 is functionally similar to its homologue, PTCH1, both of which serve as receptors in the Sonic hedgehog pathway, crucial in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis [32, 33]. While PTCH2 appears to be redundant in embryonic development, it preserves a crucial role as regards the adult epidermis [34, 35], though the molecular mechanism remains unclear. Synuclein gamma protein (SNCG) is expressed in stratum granulosum, both in embryonic development and in adults, where it functions as a keratin network modulator in the epidermis [36]. The basal cell adhesion molecule (BCAM/Lu), a membrane-bound molecule expressed by keratinocytes in inflammatory states [37], may contribute to anti-infection reactions in the bat’s skin. The accumulation of sites under positive selection in the 2nd Ig-like C2 type domain in BCAM (Fig. 2) may indicate the importance of this domain as regards molecular functioning in skin pathology, though the molecular mechanism for BCAM activity remains unclear.

LDL receptor protein 4 (LRP4) belongs to a family of LDL receptor proteins that, in dimeric form (LRP5/LRP6), serve as activating receptors for the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Apart from its role in embryogenesis, this pathway is reactivated in adults and mediates tissue regeneration following injury [38], its role lying in negative regulation against activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [39, 40]. While LRP4 shares the general structural motifs of the family, it lacks some binding motifs. LRP4 mutations severely alter pathway signalling. Bats with skin disruptions are most likely affected by changes in LRP4 structure and its subsequent effect on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway during wound healing.

Aquaporin 3 (AQP3) is expressed in keratinocytes [41] and epidermal tissues and is involved in the regulation of water and glycerol content in skin [41], thereby influencing wound healing. By regulating water flow, AQP3 facilitates epidermal cell migration and proliferation [42]. AQP3 has been shown to have a role in the healing of cutaneous burn wounds [43], which are similar to the skin disruption caused by riboflavin accumulation, tissue necrosis and subsequent oxidative stress contributing to WNS pathology [14]. The site under selection in AQP3 possibly affects the shape (and thus function) of the porin through its position in the transmembrane helix (Fig. 2).

Skin barrier integrity is an important factor in WNS pathology and survival (Fig. 3). Diseased and moribund bats with WNS skin lesions arouse from hibernation more frequently than healthy animals [19, 28]. During arousal, body temperature rises and is followed by a notable increase in activity and metabolism, following which the immune system mounts a response to the chronic infection. This reaction is often uncontrolled, causing tissue damage [20]. Annexin A1 (ANXA1), which is positively selected for in bats, acts as a mediator of glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory activity [44], and hence may be able to down-regulate such an immune response. ANXA1, which is produced by innate immunity cells such as neutrophils, has an autocrine and paracrine effect on the innate immunity cells through inhibition of vascular attachment and extravasation [45]. ANXA1 also plays an important role in adaptive immunity against chronic infectious disease [46], modulating T-cell adaptive response and directing the immune response towards the Th1/Th17 response [47, 48]. Increased expression of il-17 and il-6 [49] directs proliferation of Th17 and Th1/Th17 cells, the latter T-cells also being affected by ifnγ, which is highly variable in post-WNS populations [2]. The observed decrease in neutrophil adhesion and inefficient antibody-mediated immune response [50] may be an effect of a predominating protective Th1/Th17 response to the pathogen in later stages of the infection. The overall character of the immune reaction supports our proposal for an important role of ANXA1 in infection pathology and regulation of the immune response. As a regulator of inflammation, ANXA1 also plays a role in the outcome of inflammatory processes, wound repair and epithelial recovery [51]. The selected sites in ANXA1 are accumulated in the N-terminal region of the protein (Figs. 1 and 2) and, while they do not overlay the binding sites, they point to the importance of the area.

Similarly, TRAP also serves as an innate immune regulator, participating in the macrophage immune response and impacting on pathogen clearance from the host, most likely by affecting innate immune cell activity at the site of infection [52] by catalysing production of reactive oxygen species [53]. It also participates in down-regulation of the immune system and modulation of the Th1 response [54], which may contribute to Th1/Th17 modulation of the immune response by ANXA1. Metal binding sites in TRAP are spread along the protein sequence and do not directly coincide with the selected sites; hence, the effect of selected sites on binding capacity cannot be evaluated from a simple sequence comparison and would require further study.

The amino acid sites under positive selection do not necessarily reflect the active or binding sites of proteins. In fact, it is more probable that protein function is maintained through purifying selection (ω < 1), with a higher proportion of synonymously mutated sites conserving the active amino acid site. While a positively selected active site is unlikely, it is possible, most notably in cases of protein co-evolution with a ligand. Variable regions in the sequence are located on the protein’s surface and influence structural folding. Protein structure influences affinity and interaction to partners, which is probably the case as regards the sites detected in this study. Just as with the shape of a folded protein, protein interaction barriers may affect their biological function; hence, an absence of mechanical barriers in the area surrounding the active site is essential for physical interaction of the proteins, and positive selection in these regions may facilitate inter-protein contact.

The signal for positive selection in a protein can be allocated to specific branches on a phylogeny and can be identified at sites in the DNA sequence. Nested branch-site models require differences in the natural selection signal at an a priori defined branch, compared with the remaining diversity, which is presumed to be under purifying selection in the model. We detected positive selection in the acp5 gene in both Nearctic and Palearctic Eptesicus and in a clade of Palearctic Myotis. The Nearctic bat species Eptesicus fuscus shows limited levels of resistance to WNS infection [55], while the Palearctic species Eptesicus nilssonii rarely develops severe WNS pathology [10]. Palearctic M. myotis and M. emarginatus are representative of those species displaying a high fungal load and severe WNS pathology [10, 22], though they are able to tolerate the infection [22]; information on infection status of the third species in the Palearctic clade, M. davidii, is presently unavailable. While the mechanisms exerting selective pressure on acp5 may differ from P. destructans infection, it may now provide protection against WNS progression.

We were unable to locate branches of positive selection in some genes, most likely due to a lack of available sequences (nlrp4 = 4, nptch2 = 4, nsncg = 3) and, therefore, low sequence variability in the data set. It has also been shown that, with an increased proportion of synonymous mutations (dS), the branch site test for positive selection is more prone to false negative results [56]. Lack of selection signal heterogeneity in branches could also be assigned to host-unspecific characteristics of the pathogen, where the selective pressure would affect all species in the analysis. However, as the number of sequences in the analysis increases with additional sequencing effort (e.g. [57]), so the chances of detecting significant signs of positive selection in at least some branches increases, thus detection of a lack of positive selection in the analysis is more likely.

Inability to detect a specific branch under selection may also be affected by the use of two different haplotypes from each individual during sequence analysis, while the relationship between the two haplotypes remains unevaluated. In cases where one haplotype dominates, presence of the second haplotype in the sequence analysis may mask the signal of a positively selected haplotype in the species.

Since the protein products of genes for which positive selection has been detected are relevant to the pathology and pathophysiology of WNS, we expect them to play a role in skin integrity, wound healing and immune suppression. Hence, we can hypothesise that the selected genes contribute to the mechanism of infection tolerance in Palearctic bat species infected with WNS (Fig. 3).

Extrapolating from the devastating effects on Nearctic bat populations not previously exposed to skin injuries caused by P. destructans [6], WNS has to be the historical factor exerting enormous selection pressure on Palearctic bats. Not only could WNS have influenced genetic changes in skin integrity it has probably also influenced other rearrangements capable of preventing the devastating effects of the disease. Clear differences between Nearctic and Palearctic bats indicate at least two such rearrangements. The first is a much higher tolerance to mite and insect ectoparasites in Palearctic bats (typically 100% prevalence in breeding colonies) [58,59,60]. This results in habituation to the stress of skin injuries, which may also act as a feedback factor reducing neural sensitivity to such stimuli and their effect upon arousal from torpidity. The second difference between Palearctic and Nearctic bats relates to hibernation tactics. Most hibernating Palearctic bats disperse into a large number of less populated hibernacula rather than forming giant clusters in a single mass hibernaculum, characteristic for multiple Nearctic species [61, 62]. While this behavioural pattern appears to have declined after the WNS invasion front [63], repeated arousal caused by the grooming of infected individuals could still lead to an unintentional domino effect of multiple arousals [64]. This results in the breakdown of the core advantage of such hibernation tactics, i.e. socially controlled thermal homeostasis reducing demands on fat reserves and the need of individual behavioural skills for hibernation performance.

The above factors, suggested by the differences between Nearctic and Palearctic bats, illustrate the complex nature of skin infection and the intricacies involved in an adaptive response to an infectious agent. We show that positive selection at the genetic level is combined with the effects of increased tolerance to a parasite load and behavioural rearrangements, reducing the bat’s capacity to perform advanced hibernation tactics.

Conclusions

During hibernation, bats conserve energy by maintaining a low body temperature and minimising metabolism. While this strategy enables them to survive periods of resource scarcity, they become vulnerable to infection as their immune system fails to actively battle against infection while in torpor. Once it had invaded living tissue, the pathogen causes major damage, forming lesions and depositing metabolites that lead to necrosis. The accumulation of physiological consequences starts a cascade of adverse effects that culminates in the death of the diseased animal. We found that genes involved in the development, structure and maintenance of skin show signs of positive selection. With respect to lethal dermal infection, the epidermis likely protects heterotherms by acting as a passive barrier against infection during hibernation, a time when the animal cannot invest energy into immune reactions. The genes identified in this study may provide inspiration in designing targeted treatments for skin infections and for elucidating mechanisms involved in disease tolerance and resistance to other fungal infections, such as snake fungal disease or amphibian chytridiomycosis.

Methods

Identification of putative genes

We first selected genes with water metabolism and skin functions in the Gene Ontology database [65], then used the keywords ‘water’ and ‘epidermis’ to find genes with functions related to these keywords in Rattus norvegicus (223 genes found). We then searched UniProtKB for orthologous proteins in the Vespertilionidae and Miniopteridae families (50 genes found).

To identify genes expressed in Vespertilionidae during natural P. destructans infection, we analysed Illumina reads of M. myotis transcriptome (Accession numbers: SRX2270325, SRX2266671) by mapping them in Geneious mapper onto the reference nucleotide sequences of the selected genes with high sensitivity. We mapped the reads to the reference sequences using Geneious software version 6.1.6 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand).

From the set of 50 protein orthologs in Vespertilionidae, we identified a subset of mRNA sequences for 30 selected genes expressed in M. myotis. Sequences of 23 of the 30 genes identified were found in more than two species of Palearctic and Nearctic bats infected by P. destructans by name and taxa search in the NCBI Nucleotide database, and these were used for further analysis. We avoided searching for orthologs with BLAST due to the non-negligible possibility of gene tree to species tree discordance between paralogs and orthologs in closely related species caused by incomplete lineage sorting [66].

Assembled coding DNA sequences expressed in M. myotis were then aligned with the reference to identify conserved regions flanking a variable region in order to design primers within an exon. Primers for amplification of the selected coding regions were designed in Primer3web 4.0.0 [67, 68]. Forward and reverse gene primers were supplemented with an M13 oligonucleotide tail at the 5′ end to facilitate barcoding, forming Primer set 1. Primer set 2 contained paired barcodes and a complementary sequence to the flanking M13 tails of Primer set 1 at the 3′ end. The paired barcode sequences conformed to the barcoding protocol in SMRT Analysis 1.4 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA).

Sample collection and DNA processing

Samples were obtained from ethanol-stored tissue collections at the Institute of Vertebrate Biology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, National Animal Genetic Bank, Studenec, Czech Republic. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy® Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Halden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, additional DNA samples being obtained from the Griffin Rabies Laboratory at the State of New York Department of Health, Wadsworth, NY, USA. In total, 240 samples representing 32 species from Europe, North America and Africa were amplified with nested PCR (Additional file 2). In the first PCR, coding regions of the selected genes were amplified with the gene-specific primers, forming PCR set 1. The master mix for each gene contained 1× buffer, 0.2 mM dNTP, 0.2 μM of forward and reverse primers, 0.05 U Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1 μl of DNA. Each reaction was supplemented with MgCl2 at final concentrations given in Additional file 3. The PCR was initialised with a hot-start at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles at annealing temperatures and annealing and extension (72 °C) times specified in Additional file 3, after which the reaction was finalised at 72 °C for 3 min. The PCR product was diluted 33× and used as a template for the second PCR. In the second PCR, Primer set 2 was used for all genes, taking care that individual samples were amplified with a unique barcode combination. The PCR reaction was identical to the first PCR, with 1.5 mM of MgCl2 and the 35 cycles using the 95–53-72 °C temperature profile for 40–40-ext seconds, where ext represents extension times per gene (Additional file 3). The PCR product concentration was estimated from 2% agarose gels stained with GoldView relative to a 100 bp DNA Ladder standard (Invitrogen, available from Life Technologies, Prague, Czech Republic) in the GenoSoft 4.0 program (VWR International BVBA, Leuven, Belgium). The PCR product concentration enabled equimolar pooling of all samples for each gene. The PCR product pooled for all samples was separated on a gel, the band of expected length excised and DNA purified with the High Pure PCR Purification Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The gene products were pooled equimolarly with a final concentration of 29 ng μl− 1 and the DNA samples were sequenced commercially on a SMRT (single molecule real-time) platform (Pacific Biosciences) in two technical replicates. The DNA template library was prepared with the PacBio DNA Template Prep Kit 2.0 according to the PacBio protocol for 10 kb Template Preparation and Sequencing. The DNA template library was bound to the DNA polymerase with the PacBio DNA/Polymerase Binding Kit P4 for the first replicate, and P5 for the second replicate. Sequencing on the PacBio RS II sequencer was performed with the PacBio DNA Sequencing Kit, using C2 and C3 chemistry for the two replicates, respectively. Sequencing was performed on 2 SMRT Cells with a 180-min movie time per SMRT Cell.

Data processing

The reads were de-multiplexed as part of the commercial raw data analysis during sequencing. Data obtained from SMRT gene sequencing were assembled to the reference sequences in Geneious with coverage > 10× and percent similarity in the alignment > 50%. Processed sequence data were aligned using MAFFT version 7.307 [69] to an annotated sequence reference obtained from the NCBI database. Alignments were edited in Geneious to contain only coding sequences of the gene fitting the appropriate open reading frame from the sequence reference annotation.

Data analysis

A maximum-likelihood phylogeny of Chiropteran species obtained in a previous study [70] was used for phylogenetic analysis of positive selection. The tree was unrooted and subset to contain species present in each corresponding sequence alignment (Additional file 1). In genes where more than one individual per species was sequenced, the respective tree tip was populated with a polytomy with zero-length branches to fit the number of individuals per species analysed in the alignment.

We tested the codons in alignment for signs of positive selection, defined as rate ratio of non-synonymous and synonymous substitutions (ω = dN/dS). We used the CODEML program from the PAML 4.9 package [25] to estimate ω for the respective partial gene sequences, and variability between sites using the maximum likelihood method. Signals for positive selection were estimated from a comparison of nested models implemented in PAML using the likelihood ratio test (LRT).

The one ratio model (M0) [71, 72] sets one ω for all sites along the tested gene. A corresponding alternative model, the discrete model (M3) [4], allows a predefined number of site classes to vary in ω. While the nearly neutral model (M1) [73] does not allow ω to vary, the rate of synonymous mutations may vary at each site, with the rate of non-synonymous mutations being equal to the synonymous or equal to 0. An alternative to M1, the positive selection model (M2) [73], is derived from the neutral (M1) model and allows the rate of non-synonymous mutations to exceed the rate of synonymous mutations (ω > 1). In the beta M7 model [71], ω distribution in sites is limited to interval [0,1], meaning that the signal for predominant positive selection cannot be detected. The alternative nested model, beta&ω (M8) [74], allows the values of ω to be larger than 1.

A comparison of the one ratio (M0) model and the discrete (M3) model was used to test whether ω varied between sites. To test for positive selection signals in the codon sequence data, we paired the nearly neutral (M1) and positive selection (M2) models and the beta (M7) and beta&ω (M8) models, with the first model pair used as a null model.

The nested model’s likelihood values were compared using the LRT (twice the difference between the log-likelihoods; 2ΔlnL) of the null and alternative models. The 2ΔlnL values were then compared to χ2 distributions for M0 - M3, M1 - M2 and M7 - M8 comparisons. We corrected significance of those analyses with false discovery rates (FDR) and accepted the adjusted levels of significance at 5% as significant.

Proteins with significant results in locus-level selection were analysed for sites under positive selection, identified based on the Bayes empirical Bayes method (BEB) [75] implemented in PAML for site tests of positive selection M1 – M2 and M7 - M8. The BEB method incorporates uncertainty in maximum likelihood estimates of parameters of the ω distribution by integrating over their prior distribution. By correcting for the uncertainty in parameter estimates, BEB is well suited for small datasets [75]. For visualisation of sites within the protein structure, Phyre2 structure prediction software [76] was used to predict protein models using a reference bat species protein sequence (XP_006104612.1, XP_014396764.1, XP_006758647.1, XP_015416692.1).

In genes with sites undergoing positive selection, we identified phylogeny branches under selection using the branch-site test of positive selection [75, 77]. The branch site test is used to detect branches under positive selection pre-specified in the tested phylogeny (foreground branches), where the other background branches would undergo purifying selection. In every tree, we tested each individual branch as a foreground branch for signs of positive selection. The branch site test is performed by comparing modified branch site model A, allowing ω to vary between branches, with null model A1 where ω = 1. The nested models were tested by LRT and compared to χ2 distribution with df = 2 and p-values were adjusted with the FDR.

The monophyletic clade of Palearctic species including M. davidii, M. emarginatus and M. myotis was modelled by clade model C [78] as a foreground tested clade, which was compared to a null model M2a_rel [79]. The nested models were tested by LRT and compared to χ2 distribution with df = 1, with p-values adjusted by the FDR.

Abbreviations

- BEB:

-

Bayes empirical Bayes

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- LRT:

-

Likelihood ratio test

- WNS:

-

White-nose syndrome

References

Altizer S, Harvell D, Friedle E. Rapid evolutionary dynamics and disease threats to biodiversity. Trends Ecol Evol. 2003;18:589–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2003.08.013.

Donaldson ME, Davy CM, Willis CKR, McBurney S, Park A, Kyle CJ. Profiling the immunome of little brown myotis provides a yardstick for measuring the genetic response to white-nose syndrome. Evol Appl. 2017;10:1076–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12514.

Kimura M. Preponderance of synonymous changes as evidence for the neutral theory of molecular evolution. Nature. 1977;267:275–6.

Yang Z, Bielawski JP. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2000;15:496–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01994-7.

Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, et al. Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen? Science. 2009;323:227. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1163874.

Frick WF, Pollock JF, Hicks AC, Langwig KE, Reynolds DS, Turner GG, et al. An emerging disease causes regional population collapse of a common north American bat species. Science. 2010;329:679–82. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188594.

Hoyt JR, Langwig KE, Sun K, Lu G, Parise KL, Jiang T, et al. Host persistence or extinction from emerging infectious disease: insights from white-nose syndrome in endemic and invading regions. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016;283:20152861. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.2861.

Martínková N, Bačkor P, Bartonička T, Blažková P, Červený J, Falteisek L, et al. Increasing incidence of Geomyces destructans fungus in bats from the Czech Republic and Slovakia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13853. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013853.

Van der Meij T, Van Strien AJ, Haysom KA, Dekker J, Russ J, Biala K, et al. Return of the bats? A prototype indicator of trends in European bat populations in underground hibernacula. Mamm Biol - Z Für Säugetierkd. 2015;80:170–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2014.09.004.

Pikula J, Amelon SK, Bandouchova H, Bartonička T, Berkova H, Brichta J, et al. White-nose syndrome pathology grading in Nearctic and Palearctic bats. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180435. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180435.

Pikula J, Bandouchova H, Novotnỳ L, Meteyer CU, Zukal J, Irwin NR, et al. Histopathology confirms white-nose syndrome in bats in Europe. J Wildl Dis. 2012;48:207–11. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-48.1.207.

Gargas A, Trest MT, Christensen M, Volk TJ, Blehert DS. Geomyces destructans sp nov associated with bat white-nose syndrome. Mycotaxon. 2009;108:147–54. https://doi.org/10.5248/108.147.

Lorch JM, Meteyer CU, Behr MJ, Boyles JG, Cryan PM, Hicks AC, et al. Experimental infection of bats with Geomyces destructans causes white-nose syndrome. Nature. 2011;480:376–U129. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10590.

Flieger M, Bandouchova H, Cerny J, Chudíčková M, Kolarik M, Kovacova V, et al. Vitamin B2 as a virulence factor in Pseudogymnoascus destructans skin infection. Sci Rep. 2016;6 https://doi.org/10.1038/srep33200.

Warnecke L, Turner JM, Bollinger TK, Misra V, Cryan PM, Blehert DS, et al. Pathophysiology of white-nose syndrome in bats: a mechanistic model linking wing damage to mortality. Biol Lett. 2013;9:20130177. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2013.0177.

Verant ML, Meteyer CU, Speakman JR, Cryan PM, Lorch JM, Blehert DS. White-nose syndrome initiates a cascade of physiologic disturbances in the hibernating bat host. BMC Physiol. 2014;14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12899-014-0010-4.

Willis CKR, Menzies AK, Boyles JG, Wojciechowski MS. Evaporative water loss is a plausible explanation for mortality of bats from white-nose syndrome. Integr Comp Biol. 2011;51:364–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icr076.

Bohn SJ, Turner JM, Warnecke L, Mayo C, McGuire LP, Misra V, et al. Evidence of ‘sickness behaviour’ in bats with white-nose syndrome. Behaviour. 2016;153:981–1003. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539X-00003384.

Reeder DM, Frank CL, Turner GG, Meteyer CU, Kurta A, Britzke ER, et al. Frequent arousal from hibernation linked to severity of infection and mortality in bats with white-nose syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38920. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038920.

Meteyer CU, Barber D, Mandl JN. Pathology in euthermic bats with white nose syndrome suggests a natural manifestation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Virulence. 2012;3:583–8. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.22330.

Kjer-Nielsen L, Patel O, Corbett AJ, Le Nours J, Meehan B, Liu L, et al. MR1 presents microbial vitamin B metabolites to MAIT cells. Nature. 2012;491:717–23.

Zukal J, Bandouchova H, Brichta J, Cmokova A, Jaron KS, Kolarik M, et al. White-nose syndrome without borders: Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection tolerated in Europe and Palearctic Asia but not in North America. Sci Rep. 2016;6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19829.

Campana MG, Kurata NP, Foster JT, Helgen LE, Reeder DM, Fleischer RC, et al. White-nose syndrome fungus in a 1918 bat specimen from France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:1611–2. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2309.170875.

Zahradníková A, Kovacova V, Martínková N, Orlova MV, Orlov OL, Piacek V, et al. Historic and geographic surveillance of Pseudogymnoascus destructans possible from collections of bat parasites. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12773.

Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm088.

Humphries MM, Thomas DW, Speakman JR. Climate-mediated energetic constraints on the distribution of hibernating mammals. Nature. 2002;418:313–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00828.

Turbill C, Bieber C, Ruf T. Hibernation is associated with increased survival and the evolution of slow life histories among mammals. Proc Biol Sci. 2011;278:3355–63. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.0190.

Lilley TM, Johnson JS, Ruokolainen L, Rogers EJ, Wilson CA, Schell SM, et al. White-nose syndrome survivors do not exhibit frequent arousals associated with Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection. Front Zool. 2016;13:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12983-016-0143-3.

Verant ML, Boyles JG, Waldrep W, Wibbelt G, Blehert DS. Temperature-dependent growth of Geomyces destructans, the fungus that causes bat white-nose syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046280.

Bandouchova H, Bartonicka T, Berkova H, Brichta J, Cerny J, Kovacova V, et al. Pseudogymnoascus destructans: evidence of virulent skin invasion for bats under natural conditions, Europe. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2015;62:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12282.

Wibbelt G, Puechmaille SJ, Ohlendorf B, Mühldorfer K, Bosch T, Görföl T, et al. Skin lesions in European hibernating bats associated with Geomyces destructans, the etiologic agent of white-nose syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074105.

Motoyama J, Takabatake T, Takeshima K, Hui C. Ptch2, a second mouse patched gene is co-expressed with sonic hedgehog. Nat Genet. 1998;18:104. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng0298-104.

Takabatake T, Ogawa M, Takahashi TC, Mizuno M, Okamoto M, Takeshima K. Hedgehog and patched gene expression in adult ocular tissues. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:485–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00645-5.

Adolphe C, Nieuwenhuis E, Villani R, Li ZJ, Kaur P, Hui C, et al. Patched 1 and patched 2 redundancy has a key role in regulating epidermal differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1981–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.63.

Nieuwenhuis E, Motoyama J, Barnfield PC, Yoshikawa Y, Zhang X, Mo R, et al. Mice with a targeted mutation of patched2 are viable but develop alopecia and epidermal hyperplasia. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6609–22. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00295-06.

Ninkina NN, Privalova EM, Pinõn LGP, Davies AM, Buchman VL. Developmentally regulated expression of Persyn, a member of the Synuclein family, in skin. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246:308–11. https://doi.org/10.1006/excr.1998.4292.

Schön M, Hogenkamp V, Gregor Wienrich B, Schön MP, Eberhard Klein C, Kaufmann R. Basal-cell adhesion molecule (B-CAM) is induced in epithelial skin tumors and inflammatory epidermis, and is expressed at cell–cell and cell–substrate contact sites. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1047–53. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00189.x.

Saito-Diaz K, Chen TW, Wang X, Thorne CA, Wallace HA, Page-McCaw A, et al. The way Wnt works: components and mechanism. Growth Factors Chur Switz. 2013;31:1–31. https://doi.org/10.3109/08977194.2012.752737.

Johnson EB, Hammer RE, Herz J. Abnormal development of the apical ectodermal ridge and polysyndactyly in Megf7-deficient mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3523–38.

Ahn Y, Sims C, Murray MJ, Kuhlmann PK, Fuentes-Antrás J, Weatherbee SD, et al. Multiple modes of Lrp4 function in modulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling during tooth development. Dev Camb Engl. 2017;144:2824–36.

Qin H, Zheng X, Zhong X, Shetty AK, Elias PM, Bollag WB. Aquaporin-3 in keratinocytes and skin: its role and interaction with phospholipase D2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;508:138–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2011.01.014.

Hara-Chikuma M, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-3 facilitates epidermal cell migration and proliferation during wound healing. J Mol Med. 2008;86:221–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-007-0272-4.

Sebastian R, Chau E, Fillmore P, Matthews J, Price LA, Sidhaye V, et al. Epidermal aquaporin-3 is increased in the cutaneous burn wound. Burns. 2015;41:843–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2014.10.033.

Perretti M, D’Acquisto F. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2470.

Lim LH, Solito E, Russo-Marie F, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Promoting detachment of neutrophils adherent to murine postcapillary venules to control inflammation: effect of lipocortin 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14535–9.

Vanessa KHQ, Julia MG, Wenwei L, Michelle ALT, Zarina ZRS, Lina LHK, et al. Absence of Annexin A1 impairs host adaptive immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Immunobiology. 2015;220:614–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2014.12.001.

D’Acquisto F, Merghani A, Lecona E, Rosignoli G, Raza K, Buckley CD, et al. Annexin-1 modulates T-cell activation and differentiation. Blood. 2007;109:1095–102. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-05-022798.

Yang YH, Song W, Deane JA, Kao W, Ooi JD, Ngo D, et al. Deficiency of annexin A1 in CD4+ T cells exacerbates T cell-dependent inflammation. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2013;190:997–1007. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1202236.

Lilley TM, Prokkola JM, Johnson JS, Rogers EJ, Gronsky S, Kurta A, et al. Immune responses in hibernating little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) with white-nose syndrome. Proc R Soc B. 2017;284:20162232. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2232.

Johnson JS, Reeder DM, Lilley TM, Czirják GÁ, Voigt CC, McMichael JW, et al. Antibodies to Pseudogymnoascus destructans are not sufficient for protection against white-nose syndrome. Ecol Evol. 2015;5:2203–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.1502.

Leoni G, Neumann P-A, Kamaly N, Quiros M, Nishio H, Jones HR, et al. Annexin A1-containing extracellular vesicles and polymeric nanoparticles promote epithelial wound repair. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:1215–27. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI76693.

Bune AJ, Hayman AR, Evans MJ, Cox TM. Mice lacking tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (Acp 5) have disordered macrophage inflammatory responses and reduced clearance of the pathogen, Staphylococcus aureus. Immunology. 2001;102:103–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01145.x.

Räisänen SR, Alatalo SL, Ylipahkala H, Halleen JM, Cassady AI, Hume DA, et al. Macrophages overexpressing tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase show altered profile of free radical production and enhanced capacity of bacterial killing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:120–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.133.

Lausch E, Janecke A, Bros M, Trojandt S, Alanay Y, De Laet C, et al. Genetic deficiency of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase associated with skeletal dysplasia, cerebral calcifications and autoimmunity. Nat Genet. 2011;43:132–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.749.

Frank CL, Michalski A, McDonough AA, Rahimian M, Rudd RJ, Herzog C. The resistance of a north American bat species (Eptesicus fuscus) to white-nose syndrome (WNS). PLoS One. 2014;9:e113958. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113958.

Gharib WH, Robinson-Rechavi M. The branch-site test of positive selection is surprisingly robust but lacks power under synonymous substitution saturation and variation in GC. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1675–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst062.

Teeling EC, Vernes SC, Dávalos LM, Ray DA, Gilbert MTP. Myers E and. Bat biology, genomes, and the Bat1K project: to generate chromosome-level genomes for all living bat species. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2018;6:23–46. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022811.

Horáček I, Bartonička T, Lučan RK. Macroecological characteristics of bat geomycosis in the Czech Republic: results of five years of monitoring. Vespertilio. 2014;17:65–77.

Lucan RK. Relationships between the parasitic mite Spinturnix andegavinus (Acari: Spinturnicidae) and its bat host, Myotis daubentonii (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae): seasonal, sex- and age-related variation in infestation and possible impact of the parasite on the host condition and roosting behaviour. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2006;53:147–52. https://doi.org/10.14411/fp.2006.019.

Webber QM, Czenze ZJ, Willis CK. Host demographic predicts ectoparasite dynamics for a colonial host during pre-hibernation mating. Parasitology. 2015;142:1260–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182015000542.

Fenton MB. Population studies of Myotis lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) in Ontario. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum; 1970. http://archive.org/details/populationstudie00fent. Accessed 7 Jun 2018

Boratyński JS, Rusiński M, Kokurewicz T, Bereszyński A, Wojciechowski MS. Clustering behavior in wintering greater mouse-eared bats Myotis myotis — the effect of micro-environmental conditions. Acta Chiropterologica. 2012;14:417–24. https://doi.org/10.3161/150811012X661738.

Frick WF, Puechmaille SJ, Hoyt JR, Nickel BA, Langwig KE, Foster JT, et al. Disease alters macroecological patterns of north American bats. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2015;24:741–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12290.

Hayman DTS, Cryan PM, Fricker PD, Dannemiller NG. Long-term video surveillance and automated analyses reveal arousal patterns in groups of hibernating bats. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8:1813–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12823.

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/75556.

Altenhoff AM, Boeckmann B, Capella-Gutierrez S, Dalquen DA, DeLuca T, Forslund K, et al. Standardized benchmarking in the quest for orthologs. Nat Methods. 2016;13:425–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3830.

Koressaar T, Remm M. Enhancements and modifications of primer design program Primer3. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1289–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm091.

Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, et al. Primer3--new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e115. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks596.

Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010.

Zukal J, Bandouchova H, Bartonicka T, Berkova H, Brack V, Brichta J, et al. White-nose syndrome fungus: a generalist pathogen of hibernating bats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097224.

Yang Z, Nielsen R, Hasegawa M. Models of amino acid substitution and applications to mitochondrial protein evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:1600–11.

Goldman N, Yang Z. Codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA-sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:725–36.

Nielsen R, Yang Z. Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics. 1998;148:929–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153.

Yang Z. Maximum likelihood estimation on large phylogenies and analysis of adaptive evolution in human influenza virus a. J Mol Evol. 2000;51:423–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002390010105.

Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2003.08.013.

Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2015.053.

Zhang J. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2472–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msi237.

Bielawski JP, Yang Z. A maximum likelihood method for detecting functional divergence at individual codon sites, with application to gene family evolution. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:59–121.

Weadick CJ, Chang BSW. An improved likelihood ratio test for detecting site-specific functional divergence among clades of protein-coding genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1297–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr311.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Anna Bryjová for study design consultation; Dagmar Šoukalová and Petra Rabušicová for laboratory assistance; Josef Bryja and Alena Fornůsková from the Institute of Vertebrate Biology (Brno), Petra Hájková and Barbora Zemanová from the National Animal Genetic Bank, Studenec; and Robert Rudd and April Davis from the Griffin Rabies Laboratory for the State of New York Department of Health, Wadsworth, NY, for providing DNA and tissue material used in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (17-20286S) and by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through the National Programme of Sustainability Project IT4 Innovations - Excellence in Science (LQ1602). The funders played no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available in the NCBI Nucleotide repository, MH178037-MH178081.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IH, SM, JP, JZ and NM conceived and conceptualised the idea; ZV and NM designed the study; IH, SM, JP, JZ and NM collected the material; LJ, AZjr. and NM performed the laboratory analysis; MH, KL, JCM, PS and NM analysed the data; MH and NM wrote the manuscript, to which all authors contributed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The authors are authorised to handle free-living bats under Czech Certificate of Competency (No. CZ01341; §17, Act No. 246/1992 Coll.). The Czech Academy of Science’s Ethics Committee has reviewed and approved the Animal Use Protocol No. 169/2011 in compliance with Act No. 312/2008 Coll. on Protection of Animals against Cruelty, as adopted by the Parliament of the Czech Republic. Non-lethal bat sampling complied with Act No. 114/1992 Coll. on Nature and Landscape Protection, and was based on permits 01662/MK/2012S/00775/MK/2012, 866/JS/ 2012 and 00356/KK/2008/AOPK, issued by the Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Accession numbers of bat DNA sequences and their respective phylogeny. The coding sequences of the respective genes (alignment length in parentheses) were used for maximum likelihood analysis of natural selection in bats. The guide tree was pruned from a previously published multilocus phylogeny [70]. The scale bar is in substitutions bp− 1. (PDF 189 kb)

Additional file 2:

Bat samples amplified in this study. Populations were considered as hibernating (+) or non-hibernating (−) in the country of sample origin. Species were considered infected when Pseudogymnoascus destructans was detected in at least one individual using molecular genetic or culture experiments and positive for WNS when P. destructans was confirmed and diagnostic lesions found on skin histopathology [10, 22]. (XLSX 42 kb)

Additional file 3:

Primers and amplification conditions for genes with a skin integrity or water metabolism function. Primer pairs were designed for genes expressed in Myotis myotis with white-nose syndrome (Accession numbers: SRX2270325, SRX2266671). (XLSX 47 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Harazim, M., Horáček, I., Jakešová, L. et al. Natural selection in bats with historical exposure to white-nose syndrome. BMC Zool 3, 8 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-018-0035-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-018-0035-4