Abstract

Background

Translational regulation played an important role in the correct folding of heterologous proteins to form bioactive conformations during biogenesis. Translational pausing coordinates protein translation and co-translational folding. Decelerating translation elongation speed has been shown to improve the soluble protein yield when expressing heterologous proteins in industrial expression hosts. However, rational redesign of translational pausing via synonymous mutations may not be feasible in many cases. Our goal was to develop a general and convenient strategy to improve heterologous protein synthesis in Pichia pastoris without mutating the expressed genes.

Results

Here, a large-scale deletion library of ribosomal protein (RP) genes was constructed for heterologous protein expression in Pichia pastoris, and 59% (16/27) RP deletants have significantly increased heterologous protein yield. This is due to the delay of 60S subunit assembly by deleting non-essential ribosomal protein genes or 60S subunit processing factors, thus globally decreased the translation elongation speed and improved the co-translational folding, without perturbing the relative transcription level and translation initiation.

Conclusion

Global decrease in the translation elongation speed by RP deletion enhanced co-translational folding efficiency of nascent chains and decreased protein aggregates to improve heterologous protein yield. A potential expression platform for efficient pharmaceutical proteins and industrial enzymes production was provided without synonymous mutation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pichia pastoris is a widely used platform for heterologous protein expression, which is a “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) microorganism. Unlike the bacterial expression systems, which lack the modification enzymes, Pichia pastoris is able to produce heterologous proteins with post-translational modifications, especially glycosylation, which is crucial for optimal properties of many pharmaceutical proteins. Over 5000 proteins were manufactured in P. pastoris (data from RCT Pichia technology), most of which are industrial enzymes and biopharmaceutical proteins [1, 2]. However, due to the remarkable codon preference and tRNA content against the other species, heterologous proteins expressed in Pichia pastoris often encounter folding problem, which severely limited their production efficiency [3]. To solve this problem, current strategies mainly focus on codon optimization, protein refolding, and secretion pathway engineering [2, 4, 5]. However, these methods are successful only for a small fraction of proteins, and intensive trials and modifications are often necessary.

Recent studies have revealed that the amino acid sequence does not guarantee correct folding of proteins. The translational pausing sites, which are mediated by clustered but non-consecutive slow-translating codons, coordinate protein biosynthesis and co-translational folding [6]. Translational pausing sites are highly correlated with protein structural domains [7,8,9]. Therefore, rational design of translational pausing sites via synonymous substitutions may largely enhance the folding efficiency of heterologous proteins and thus yield large amount of active proteins [10, 11]. Although the small proteins with robust folding landscape and rigid native structure do not need translational pausing to fold correctly [12], global perturbation of translational pausing leads to massive aggregation in bacteria [13], demonstrating that a large fraction of the proteins fold in a co-translational folding-dependent manner. For example, green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a eukaryotic protein containing 11 beta-sheet structures and its folding yield was significantly increased by co-translational folding in E. coli [14]. Another protein, phytase (Phy) from Citrobacter amalonaticus CGMCC 1696, has 95% homology to E. coli-derived phytase which consists of one α-domain containing five α-helices and a β-hairpin, and one α/β-domain including seven β-sheets and four α-helices [15]. These proteins are beta-sheet rich or multi-domain and aggregation prone, which may require higher co-translational folding efficiency.

Although a rational design of translational pausing showed its distinguished power in optimizing soluble expression of heterologous proteins, it still necessitates intensive computational and experimental efforts, which often includes numerous synonymous mutations. In addition, rational design requires structural knowledge of the target protein, which is often not available. These obstacles restricted the application of this strategy. Therefore, a more general expression platform is preferred in case that the rational design of translational pausing could not be applied. The microorganisms tend to suppress translation system under stress conditions to save energy, including oxidative stress [16], hypoxia, unfolded protein stress [17,18,19] and extensive protein expression [20,21,22]. In P. pastoris, overexpression of xylanase A leads to significant down-regulation of numerous ribosomal proteins, including 21 large subunit ribosomal proteins (RPL) and 9 small subunit ribosomal proteins (RPS) [23]. Global deceleration of translation elongation would enhance the folding efficiency of proteins [6, 16] and thus may provide a universal expression platform for heterologous proteins without the necessity of intensive synonymous mutations. Notably, a number of ribosomal proteins (RPs) in P. pastoris are non-essential, i.e., deletion strains of these RPs are not lethal, although impairing the growth, indicating that the translation rate is down-regulated. This provided a number of candidates of “slow ribosomes” to enhance the soluble expression of heterologous proteins.

In this study, 27 RP deletion strains of P. pastoris were analyzed and two heterologous proteins, eGFP and Phy, driven by the AOX1 promoter, were expressed in them. RP deletion did not alter the relative mRNA level and translation initiation efficiency. 16 RP deletion strains significantly improved the expression efficiency, indicating that the decelerated translation elongation promoted the co-translational folding of heterologous proteins.

Results

Expression efficiency analysis of heterologous protein in RP deletion strains

Due to the incomplete annotation of P. pastoris genome, the P. pastoris GS115 genome (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/blast/moderated/?project=orcae_Picpa) was searched for the RP homologs using the RP gene sequences of S. cerevisiae [24]. Compared to 79 RPs encoded by 138 genes in S. cerevisiae [25], 77 RPs are encoded by 86 genes and the homologous proteins of Rpl27 and Rpl41 from S. cerevisiae are missing in P. pastoris (Additional file 1: Table S1). Only nine RPs are encoded by a pair of paralogous genes that, in most cases, encode identical or very similar protein products in P. pastoris (Additional file 2: Table S2). These findings indicated that the number and composition of the RPs of two budding yeasts are totally different. In this study, 27 RP deletion strains were successfully constructed, which suggest these RPs are non-essential in P. pastoris (Additional file 2: Figure S1, Additional file 3: Table S5).

P. pastoris strains were transformed only with low amounts of the MssI-linearized expression cassettes (0.5–1 μg of DNA) to avoid multi-copy integration [26] and yield single copy eGFP or Phy gene in the P. pastoris GS115 genome confirmed by the quantitative real-time PCR (Additional file 2: Table S3). In total, 16 RP deletion strains significantly increased the expression of both eGFP and Phy (Fig. 1, Additional file 2: Figure S2). Most of these “enhancing deletion strains” (12 out of 16) were RPL (RP of the large subunit) deletants, indicating that RPLs are important determinants of heterologous protein expression in P. pastoris.

Heterologous protein expression in RP deletion strains. Specific expression of two heterologous proteins (a eGFP and b Phy) in the wild-type and RP deletion strains. The wild-type strain transformed with empty vector pPICZαA was used as negative control. All strains were fermented in the liquid BMMY for 120 h by feeding 1% methanol per 24 h. Expression levels were measured by the relative fluorescence units (RFU) or enzyme activity and OD600. Error bars represent s.d. across three biological replicates. Significance against wild type is indicated as: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, t test

The relative transcription and translation initiation of Phy in RP deletion strains

To verify the transcription level and translation initiation efficiency in RP deletion strains, the typical “enhancing” strains of rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rps25∆ and a “non-enhancing” strain of rps7∆ expressing Phy are chosen as representative strains (Fig. 2a, Additional file 2: Figure S3). Also, the growth pattern of RP deletion strains was changed. After 12 h, all strains were already out of exponential phase. The RP deletants grew much slower after 24 h, while the wild-type strain grew constantly till 120 h (Fig. 2b, Additional file 2: Figure S3d). Previous to this, these RP deletion strains were complemented with the corresponding RP actuated by the strongly constitutive promoter GAP. The RP complementation strains showed more similar heterologous protein expression relative to the RP deletion strains, indicating that it was actually the RP deletions that caused the observed phenotypes (Fig. 2a, b, Additional file 2: Figures S3, S4). To be noted, the specific activity of Phy in RP-complemented strains was similar to the wild-type level (~ 5 U/OD600), much lower than the values (10 ~ 20 U/OD600) in rpl38∆ and rpl9a∆ strains, suggesting that the ribosome performance is the major factor of the specific activity of heterologous protein.

Phy expression in RP deletion strains and wild type. a, b Phy expression profiles of the rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rps7∆ and rps25∆ strains relative to the wild-type strain. a Activity per OD600; b Growth curve. c, d Expression of the Phy in transcription level and translation level (RNC-mRNA) of rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rps7∆, rps25∆ and wild-type strains at the early and middle stage of fermentation. Expression levels were measured using next-generation sequencing, evaluated using rpkM as unit

Next, we tested the mRNA abundance and translation initiation of Phy in RP deletion strains. While these strains accumulate heterologous proteins in a time-dependent manner, the relative mRNA level of the Phy remained constant over the time and across the strains, with a standard deviation of only 50 parts per million (ppm), determined by mRNA-seq quantified using reads per kilobase per million reads (rpkM) (Fig. 2c). Meanwhile, the ribosome–nascent chain complex (RNC) mRNA (RNC-mRNA, mRNAs attached to the ribosomes) of Phy, representing the Phy mRNA which entered the translation process, remained also constant over the time and across the strains, with a standard deviation of 153 ppm, determined by RNC-seq (Fig. 2d). These results demonstrated that deletion of the non-essential RPs did not influence the relative transcription and translation engagement of the heterologous mRNA at all.

The above-mentioned results indicated that the “enhancing” RP deletion strains may increase the activity of heterologous proteins by facilitating their folding. To further determine whether the enhanced folding occurs during the translation or after the translation, we analyzed the relative mRNA and RNC-mRNA level of molecular chaperones. In general, RNA-seq and RNC-seq data revealed almost no significant change in the expression level of chaperones (Additional file 4: Tables S6, S7). This implied that the co-translational folding was enhanced.

Delay of 60S ribosomal subunit assembly enhances heterologous protein expression

Yeast non-essential RPs play important roles in ribosome biogenesis and function [27]. Deletion of particular RPs can delay or impair subunit assembly [27,28,29,30,31]. To evaluate the global impact of RP repression on ribosome assembly and translation, polysome profiles were performed for several RP deletion strains expressing Phy in high-salt conditions (to disrupt non-translating 80S monosomes) (Fig. 3a–c). The “enhancing” strains of rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rpl9b∆, rps25∆ and rps27a∆ exhibited lower 60S ribosomal subunits than the wild-type strain (Fig. 3a, c), indicating that the 60S subunit availability is decreased. In contrast, the “non-enhancing” strains, rpl29∆, rps7∆ and rps27b∆, showed almost identical 60S peaks as the wild type (Fig. 3b, c).

Ribosome assembly in RP deletion strains and 60S processing factor deletion strains, analyzed by polysome profiles. a, b Polysome profiles of the “enhancing” a and “non-enhancing” b strains in relation to wild-type strain showed that the former had the lower 60S level. c Polysome profiles of RP deletion paralogs. The “enhancing” strain rps27a∆ showed a reduced level of 60S ribosomal subunits relative to its paralog deletion strain (“non-enhancing”). d, e Phy expressional profiles of non-essential 60S processing factor deletion strains relative to wild type. d Activity per OD600; e Growth curve. f Relative to wild type, polysome profiles for rei1Δ and nop12Δ strains showed reduction of the 60S subunit level

To validate this finding, two 60S subunit processing factors were knocked out, nop12 and rei1 [32,33,34], to delay 60S subunit assembly. Both deletion strains showed lower 60S peak in the polysome profiles as expected, and half-mer peaks appeared after monosome/polysome (Fig. 3f), which represent that 48S initiation complexes exist on actively translated mRNAs [31, 35]. Interestingly, the Phy expression in these deletion strains was also enhanced robustly, both measured using unit/OD600 (Fig. 3d, e) and unit ml−1 (Additional file 2: Figure S5). These results indicated that the 60S assembly delay might be necessary for the expression enhancement of heterologous proteins.

RP deletion promotes co-translational folding of Phy and decreases protein aggregates

Although the relative number of mRNA molecules involved in the translation did not change (Fig. 2d), decreased availability of 60S subunit would reduce the translation initiation rate, which should result in lower protein production rate. However, the final protein level of Phy was increased. Therefore, the only explanation would be a much lower protein degradation rate, which indicates remarkably better folding efficiency of Phy. According to the “pause to fold” theory [6], this could be only achieved by slower translation elongation speed. Indeed, higher fraction of polyribosomes were observed in the “enhancing” strains, including the nop12 and rei1 deletion strains, indicating remarkably slower translation elongation speed along the mRNA [16]. The slower elongation speed could be easily explained by defective 60S subunit.

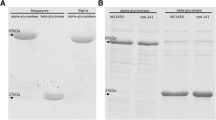

To further validate the “pause to fold” hypothesis in our case, Phy with the N-terminal HA-tag was expressed to assess the proteolytic susceptibility of Phy nascent chains, which reflects the co-translational folding efficiency, similar to our previous work [10]. After 12 h induction by methanol, the RNCs were isolated and then digested using proteinase K. The Phy nascent chains in “enhancing” strains rpl38∆, rpl9a∆ and rps25∆ were significantly proteinase K resistant relative to wild type, showing better co-translational folding efficiency (Fig. 4a, Additional file 2: Table S4). In contrast, the Phy nascent chain in the rps7∆ strain was as vulnerable as in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4a, Additional file 2: Table S4).

Co-translational folding efficiency of Phy nascent chains and protein aggregates in RP deletion strains. a Assessment of co-translational folding efficiency of Phy nascent chains in wild-type and RP deletion strains. After the limited proteinase K digestion, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, and the remaining Phy was visualized by western blotting. The optical density of Phy band was calculated and the RNC aliquots from the same samples with proteinase K digestion were normalized to those with no proteinase K digestion. b Quantitative analysis of protein aggregates extracted from wild-type and RP deletion strains transformed with Phy which is glycosylated in P. pastoris [57]. The samples were subject to SDS-PAGE separation followed by Coomassie blue staining, and Phy was visualized by western blotting. c Quantification of Phy aggregate level as shown in b. The aggregated Phy signals were normalized to totals and wild-type strain transformed with Phy was set as 100%. Unpaired t test of GraphPad Prism 6 was used for statistical analysis. Significant difference of Phy aggregates level is indicated as: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent s.d. of at least three independent experiments

In another aspect, better co-translational folding efficiency should be accompanied by less protein aggregates. Indeed, the “enhancing” strains of rpl38∆, rpl9a∆ and rps25∆ showed less Phy aggregates than the wild-type strains, while the “non-enhancing” rps7∆ showed stronger protein aggregates of intracellular total proteins and Phy (Fig. 4b, c). To be on the safe side, our method of isolating insoluble proteins was validated using bovine serum albumin fraction V (BSA) as a representative indicator of soluble proteins (Additional file 2: Figure S6) [36].

Taken together, these data revealed that slower translation elongation speed caused by the non-essential RP deletion enhanced heterologous protein expression by increasing the co-translational folding efficiency of nascent chains and decreasing protein aggregates.

Discussion

In S. cerevisiae, 60S subunit assembly defect by RP deletion increases Gcn4 expression to repress translation and extend life span [29, 31]. In this study, defective 60S subunit assembly by RP deletion reduced protein aggregates of both heterologous (Fig. 4c) and endogenous (Fig. 4c) proteins. Although aggregation of endogenous proteins could be a result of expressing the heterologous protein, these findings imply that lower protein aggregates by RP deletion may be beneficial to save energy and increase yeast life span.

In the excellent hosts for recombinant protein production, such as E. coli and P. pastoris, one of the bottlenecks for most heterologous protein synthesis is protein folding [37, 38]. In protein synthesis, folding quality control in the stage of co-translation and post-translation is crucial for forming the native conformation and decreasing protein misfolding and aggregation [39,40,41]. Current strategies for improving heterologous protein folding mainly focused on the past-translational phase, including co-expression of chaperones and helpers in cytoplasm or endoplasmic reticulum and glycosylation engineering in P. pastoris [3,4,5, 42,43,44]. However, a proteome-wide study of chaperonin-dependent protein folding indicates that folding of many proteins is not strictly dependent on molecular chaperones like GroEL/ES [45]. In this paper, the mRNA-seq and RNC-seq data showed that the abundance of genes encoding chaperones was not significantly increased to the level observed in the “enhancing” strains, suggesting that the post-translational folding executed by chaperones may not change (Additional file 4: Tables S6, S7). Besides, approximately 70% of newly translated polypeptides rely on co-translational folding of ribosome-associated Hsp70 in eukaryotes, which are, mostly, long, multi-domain, beta-sheet-rich, aggregation-prone, slow-translational, and slower folded proteins [41]. The reporter proteins eGFP and Phy used in this study meet the feature of slower folded proteins [14, 15], which may require slow translation elongation rate for co-translational folding. Thus, an overall decrease in elongation speed by deletion of non-essential RP improved their co-translational folding efficiency (Fig. 4a). More importantly, these deletion strains create an optimized translation scenario for heterologous proteins. This is convenient for heterologous protein production without a priori knowledge of protein structures and rational design of translational pausing sites [10, 12].

Intriguingly, the higher fraction of polyribosomes did not guarantee a slower elongation speed. The rps7∆ strain exhibited a higher fraction of polyribosomes (Fig. 3b). However, the Phy expression was not enhanced and more protein aggregates were found in the rps7∆ strain, indicating that the translation elongation was not decelerated. A reasonable explanation would be that the rps7∆ strain possesses more ribosomes. Indeed, more rRNAs were found in the rps7∆ strain (Additional file 2: Figure S7). More ribosomes resulted in higher translation initiation rate. Considering that the relative mRNA level is not changed (Fig. 2c), higher translation initiation rate will lead to more ribosomes in the polysome fraction [46]. This is echoed by the fact that the rps7∆ strain showed the same 60S subunit peak as the wt, while all “enhancing” strains showed lower 60S ribosomal subunit than wt (Fig. 3).

In addition, codon optimization, which replaces rare codons with the preferred codons without amino acid alteration, can accelerate translation and may enhance heterologous protein production [47]. For example, the enzyme activity of a codon-optimized endoglucanase gene from Trichoderma reesei was increased 24% relative to the natural gene in P. pastoris [48]. However, codon optimization perturbs the co-translational folding of many proteins because of translation initiation or elongation acceleration, which may cause protein misfolding and limit the production of heterologous protein [49, 50]. In this work, enhancing the co-translational folding of heterologous protein by RP deletion greatly improved the expression of codon-optimized eGFP and Phy in P. pastoris, suggesting that these RP deletion strains were suitable for decreasing the translation rate of the codon-optimized gene, thus increasing the yield of soluble and bioactive proteins while lowering the cost of manufacturing. Furthermore, many heterologous genes have been transformed in Pichia pastoris for biofuel production in recent years [51,52,53]. A convenient platform was developed to improve heterologous protein expression in Pichia pastoris, which may contribute to heterologous pathway expression for synthetic biology applications, such as biofuel production.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the “slow ribosomes” were constructed to enhance the soluble expression of heterologous proteins based on improved co-translational folding in P. pastoris. Loss of non-essential ribosomal proteins increased heterologous protein synthesis without changing the relative transcription level and translation ratio of heterologous protein. Further studies found that 60S subunit assembly defect was a key determinant of increased heterologous protein yield with the improved co-translational folding efficiency of nascent chains. According to the principle of “pause to fold” which is slowing down the elongation speed at a certain region of mRNA coordinates co-translation folding and protein synthesis [6, 46, 54,55,56], defective 60S subunit assembly by RP deletion enhances co-translational folding efficiency of nascent chains and decreases protein aggregates to improve heterologous protein yield. Therefore, our work opens an avenue for improving heterologous protein production based on elaborate protein quality control. Further studies will focus on the validation of these RP deletion strains in more pharmaceutical proteins and industrial enzymes.

Methods

Strains and plasmids

Escherichia coli strain TOP10 was used for recombinant DNA manipulation. Pichia pastoris GS115 (Invitrogen) expressing eGFP or Phy was used as the wild-type (wt) strain and all deletion strains used in this study were derived from it. The pPICZαA (Invitrogen) vector including AOX1 promoter was used to express the heterologous protein of eGFP and Phy from Citrobacter amalonaticus CGMCC 1696 [57]. The pGAPZA (Invitrogen) vector containing GAP promoter was used to construct the RP complementation strains.

Transformation and cultivation conditions

Electroporation was used for P. pastoris transformation and transformants were screened on YPDSZ (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose, 2% agar, 1 M sorbitol, 100 µg ml−1 Zeocin). To avoid multi-copy integration, the method from Thomas et al. was employed [26]. The plasmids containing eGFP or Phy gene were linearized by MssI enzyme. Then low amounts of MssI-linearized expression cassettes (0.5 to 1 μg of DNA) were transformed into P. pastoris strains. After verification by PCR, positive transformants were cultivated in a liquid medium BMGY [1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1.34% YNB (yeast nitrogen base without amino acids), 1% glycerol, 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0)] for 20–24 h (2 to 6 OD600) in a 50 ml shake flask. Then the strains were washed with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) or sterile water and transferred to 250 ml shake flask containing 25 ml BMMY [1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1.34% YNB, 1% methanol, 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0)] with initial OD600 = 1.0. The fed-batch fermentation was proceeded to express eGFP and Phy for 120 h by feeding 1% methanol per 24 h. All liquid culture was performed at 30 °C and 250 rpm. The samples for RNA-seq and RNC-seq were taken before adding methanol at 24, 48 and 72 h after growth in BMMY medium with an initial OD600 of 1.0. In addition, the samples for polysome profiles, determination of nascent chain folding, and isolation of protein aggregates were taken at 12 h in the same cultivation conditions.

Construction of RP and 60S assembly factor deletion strains

Deletants were generated by PCR-mediated gene disruption based on homology recombination as follows [58]. The Cre/mutated lox system was used for recycling the Zeocin (Invitrogen) resistance marker. The Cre-ZeoR cassette including cre gene amplified from the plasmid pSH47 and Sh ble gene was constructed by ligating the EcoRI/SacII-digested fragment of cre gene to pPICZA (Invitrogen). Then overlapped 30–40 bp nucleotides were designed to fuse the Cre-ZeoR cassette with two homology fragments, which is the flank of the deleted region. The purified fusion PCR products were transformed into the competent cells of P. pastoris by electroporation with the parameters set at 1.5 kV, 200 ω and 25 µF. YPDSZ plates were used to screen for Zeocin-resistant transformants and positive transformants were identified by PCR. To recycle the Zeocin resistance marker, positive transformants were shifted to YPM liquid medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1% methanol) for induction culture up to 96–120 h by feeding 1% methanol per 24 h. Then the cells were streaked after methanol induction on the YPD plates. Single colonies were diluted in sterile water and then spotted on YPD and YPDZ (YPD plus 100 µg ml−1 Zeocin) plates to test whether the Cre-ZeoR cassette had been removed. Finally, the marker-removed deletants were confirmed by PCR. All primers were listed in Additional file 3: Table S5.

Isolation of ribosome–nascent chain complexes

The method of ribosome–nascent chain complexes (RNCs) extraction was generated as described before with appropriate revision [59, 60]. P. pastoris strains (10–20 OD600) were pre-treated with 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at 30 °C and 250 rpm and washed with 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), followed by incubation with 1 ml buffer I (20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 10 mM DTT (or 0.5% β-mercaptoethanol), and 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide) for 10 min at 30 °C. After collecting cells by centrifugation (3000g) for 3 min at 4 °C, pellets were resuspended with 1 ml buffer II (20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 1.2 M sorbitol, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 150 U ml−1 lyticase (Yeasen, shanghai, China), 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Each sample was divided into two aliquots to extract RNC-RNA and total RNA. For RNCs extraction, once more pellets were collected by centrifugation (3000g) for 3 min at 4 °C, followed by adding 1 ml ribosome buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide) with 1% Triton X-100. After 10 min ice bath, cell lysates were centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. Supernatants were transferred on the surface of 12.5 ml sucrose buffer (30% sucrose in ribosome buffer). RNCs were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (185,000g) in a Type 70 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 5 h at 4 °C. Another aliquot was suspended with 1 ml TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) for total RNA extraction.

RNA extraction, RNA sequencing and data analysis

The total RNA and RNC-RNA extraction was carried out as previously described [60]. In brief, isolation of total RNA and RNC-RNA was used by TRIzol Reagent, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two biological replicates of total RNA and RNC-RNA were performed for subsequent RNA-seq, respectively. The polyA + mRNA was selected from the total RNA and RNC-RNA samples by RNA Purification Beads (Illumina). The cDNA library products were generated using NEBNext Ultra II RNA library prep kit (NEB) and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq X Ten. Library construction and sequencing were performed at Shenzhen Chi-Biotech Corporation. High-quality reads were kept for the sequence analysis by the Illumina quality filters. The raw sequencing data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE116415). The mRNA and RNC-mRNA abundance was normalized using rpkM [61]. Genes with > 10 mapped reads were considered as quantified genes [62]. The edgeR package method was adopted to analyze the differential expression genes [63].

Polysome profiles

The polysome profiles were performed by modification of the previously described methods [29, 64]. P. pastoris strains were cultured in liquid medium BMMY for 12 h and pre-treated with 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide for 15 min at 30 °C, 250 rpm. Then cells were collected by centrifugation (3000g) for 3 min at 4 °C, washed with 5 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 140 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1% Triton X-100, 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide) and suspended in 1 ml lysis buffer. Cells were transferred and lysed by MiniBeadbeater (Biospec products) with 730 mg acid-washed glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 × 30 s times at intervals of 1 min on ice. The step of lysis was executed in a 4 °C cold room. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation (3000g) for 5 min at 4 °C, and transferred to 1.5 ml tubes for further centrifugation (10,000g) for 10 min. 20 (or 25, Fig. 3c) A260 units were loaded on the surface of 10–50% linear sucrose gradients (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 15 mM MgCl2, 800 mM KCl, 100 µg ml−1 cycloheximide) and ultracentrifuged at 39,000 rpm at 4 °C by SW40 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 2 h. Finally, gradients were collected from the top and measured at 260 nm by Gradient Station (Biocomp).

Determination of nascent chain folding state

Firstly, cells were grown in BMMY with an initial OD600 = 1.0 for 12 h. RNCs pellet was isolated and softly resuspended in 100 µl of the ribosome buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM KCl). All samples were monitored at 260 nm immediately and adjusted to 10 A260 units ml−1. 20 µl sample was digested by gently mixing with 0.8 ng µl−1 proteinase K and incubated on ice for 2, 5 and 10 min, respectively. Then the reactions were mixed immediately with SDS loading buffer and heated at 100 °C for 5 min. The fraction of nascent chain was analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE and visualized by western blot. The ImageJ software was used to quantify the bands.

Isolation of protein aggregates

The procedure of protein aggregates was prepared according to a previously reported protocol [65]. 50 OD600 units of 12 h-inductional strains in BMMY were harvested by centrifugation (3000g) for 3 min at 4 °C, and pellets were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Pellets were washed with 20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.8) and resuspended in buffer II [20 mM potassium phosphate pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 0.1% Tween 20, protease inhibitor cocktail (MedChemExpress), 1 mM PMSF (Yeasen, shanghai, China), 150 U ml−1 lyticase and 1.25 U ml−1 Benzonase (Yeasen, shanghai, China)], incubated for 15 min at 30 °C and chilled on ice for 5 min. After sonication, the samples were collected by centrifugation (200g) for 20 min. The supernatants were diluted to identical protein concentrations and taken as input control (total). Aggregates were sedimented by centrifugation (16,000g) for 20 min at 4 °C. The aggregated proteins were washed twice with buffer II (20 mM potassium phosphate pH 6.8, 2% (v/v) NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail), sonicated and centrifuged at 16,000g at 4 °C for 20 min. Protein aggregates were sonicated with rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2% CHAPS, 2 M thiourea, 20 mM DTT, 1% SDS) [36], boiled in SDS sample buffer, together with totals separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Coomassie blue staining and western blotting.

Abbreviations

- RP:

-

ribosomal protein

- RPL:

-

large subunit ribosomal protein

- RPS:

-

small subunit ribosomal protein

- eGFP:

-

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- Phy:

-

phytase

- RNC:

-

ribosome–nascent chain complex

- RFU:

-

relative fluorescence unit

- rpkM:

-

reads per kilobase per million reads

- ppm:

-

parts per million

References

Fickers P. Pichia pastoris: a workhorse for recombinant protein production. Curr Res Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;2:354–63.

Yang Z, Zhang Z. Engineering strategies for enhanced production of protein and bio-products in Pichia pastoris: a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36:182–95.

Puxbaum V, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Quo vadis? The challenges of recombinant protein folding and secretion in Pichia pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:2925–38.

Damasceno LM, Huang CJ, Batt CA. Protein secretion in Pichia pastoris and advances in protein production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:31–9.

Juturu V, Wu JC. Heterologous protein expression in Pichia pastoris: latest research progress and applications. ChemBioChem. 2018;19:7–21.

Zhang G, Hubalewska M, Ignatova Z. Transient ribosomal attenuation coordinates protein synthesis and co-translational folding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:274–80.

Thanaraj TA, Argos P. Ribosome-mediated translational pause and protein domain organization. Protein Sci. 1996;5:1594–612.

Zhang G, Ignatova Z. Generic algorithm to predict the speed of translational elongation: implications for protein biogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5036.

Saunders R, Deane CM. Synonymous codon usage influences the local protein structure observed. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6719–28.

Chen W, Jin J, Gu W, Wei B, Lei Y, Xiong S, Zhang G. Rational design of translational pausing without altering the amino acid sequence dramatically promotes soluble protein expression: a strategic demonstration. J Biotechnol. 2014;189:104–13.

Hess AK, Saffert P, Liebeton K, Ignatova Z. Optimization of translation profiles enhances protein expression and solubility. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127039.

Huang W, Liu W, Jin J, Xiao Q, Lu R, Chen W, Xiong S, Zhang G. Steady-state structural fluctuation is a predictor of the necessity of pausing-mediated co-translational folding for small proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:186–92.

Fedyunin I, Lehnhardt L, Bohmer N, Kaufmann P, Zhang G, Ignatova Z. tRNA concentration fine tunes protein solubility. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3336–40.

Ugrinov KG, Clark PL. Cotranslational folding increases GFP folding yield. Biophys J. 2010;98:1312–20.

Lim D, Golovan S, Forsberg CW, Jia ZC. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli phytase and its complex with phytate. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:108–13.

Zhong J, Xiao C, Gu W, Du G, Sun X, He QY, Zhang G. Transfer RNAs Mediate the Rapid Adaptation of Escherichia coli to Oxidative Stress. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005302.

Wouters BG, Koritzinsky M. Hypoxia signalling through mTOR and the unfolded protein response in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:851–64.

Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Willis AE. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40:228–37.

Pincus D, Aranda-Diaz A, Zuleta IA, Walter P, El-Samad H. Delayed Ras/PKA signaling augments the unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:14800–5.

Jürgen B, Lin HY, Riemschneider S, Scharf C, Neubauer P, Schmid R, Hecker M, Schweder T. Monitoring of genes that respond to overproduction of an insoluble recombinant protein in Escherichia coli glucose-limited fed-batch fermentations. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;70:217–24.

Jürgen B, Hanschke R, Sarvas M, Hecker M, Schweder T. Proteome and transcriptome based analysis of Bacillus subtilis cells overproducing an insoluble heterologous protein. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:326–32.

Rinas U. Synthesis rates of cellular proteins involved in translation and protein folding are strongly altered in response to overproduction of basic fibroblast growth factor by recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Prog. 1996;12:196–200.

Lin XQ, Liang SL, Han SY, Zheng SP, Ye YR, Lin Y. Quantitative iTRAQ LC-MS/MS proteomics reveals the cellular response to heterologous protein overexpression and the regulation of HAC1 in Pichia pastoris. J Proteomics. 2013;91:58–72.

De Schutter K, Lin YC, Tiels P, Van Hecke A, Glinka S, Weber-Lehmann J, Rouze P, Van de Peer Y, Callewaert N. Genome sequence of the recombinant protein production host Pichia pastoris. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:561–6.

Steffen KK, McCormick MA, Pham KM, MacKay VL, Delaney JR, Murakami CJ, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy BK. Ribosome deficiency protects against ER stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;191:107–18.

Vogl T, Ruth C, Pitzer J, Kickenweiz T, Glieder A. Synthetic core promoters for Pichia pastoris. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3:188–91.

Woolford JL Jr, Baserga SJ. Ribosome biogenesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2013;195:643–81.

Dresios J, Panopoulos P, Synetos D. Eukaryotic ribosomal proteins lacking a eubacterial counterpart: important players in ribosomal function. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1651–63.

Steffen KK, MacKay VL, Kerr EO, Tsuchiya M, Hu D, Fox LA, Dang N, Johnston ED, Oakes JA, Tchao BN, et al. Yeast life span extension by depletion of 60S ribosomal subunits is mediated by Gcn4. Cell. 2008;133:292–302.

Wild T, Horvath P, Wyler E, Widmann B, Badertscher L, Zemp I, Kozak K, Csucs G, Lund E, Kutay U. A protein inventory of human ribosome biogenesis reveals an essential function of exportin 5 in 60S subunit export. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000522.

Mittal N, Guimaraes JC, Gross T, Schmidt A, Vina-Vilaseca A, Nedialkova DD, Aeschimann F, Leidel SA, Spang A, Zavolan M. The Gcn4 transcription factor reduces protein synthesis capacity and extends yeast lifespan. Nat Commun. 2017;8:457.

Lebreton A, Saveanu C, Decourty L, Rain JC, Jacquier A, Fromont-Racine M. A functional network involved in the recycling of nucleocytoplasmic pre-60S factors. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:349–60.

Hung NJ, Johnson AW. Nuclear recycling of the pre-60S ribosomal subunit-associated factor Arx1 depends on Rei1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3718–27.

Talkish J, Campbell IW, Sahasranaman A, Jakovljevic J, Woolford JL Jr. Ribosome Assembly Factors Pwp1 and Nop12 Are Important for Folding of 5.8S rRNA during Ribosome Biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:1863–77.

Moy TI, Boettner D, Rhodes JC, Silver PA, Askew DS. Identification of a role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cgr1p in pre-rRNA processing and 60S ribosome subunit synthesis. Microbiology. 2002;148:1081–90.

Chen Y, Li Y, Zhong J, Zhang J, Chen Z, Yang L, Cao X, He QY, Zhang G, Wang T. Identification of missing proteins defined by chromosome-centric proteome project in the cytoplasmic detergent-insoluble proteins. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:3693–709.

Baneyx F, Mujacic M. Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1399–408.

Gasser B, Saloheimo M, Rinas U, Dragosits M, Rodriguez-Carmona E, Baumann K, Giuliani M, Parrilli E, Branduardi P, Lang C, et al. Protein folding and conformational stress in microbial cells producing recombinant proteins: a host comparative overview. Microb Cell Fact. 2008;7:11.

Nicola AV, Chen W, Helenius A. Co-translational folding of an alphavirus capsid protein in the cytosol of living cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:341.

Cabrita LD, Dobson CM, Christodoulou J. Protein folding on the ribosome. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:33–45.

Willmund F, del Alamo M, Pechmann S, Chen T, Albanese V, Dammer EB, Peng J, Frydman J. The cotranslational function of ribosome-associated Hsp70 in eukaryotic protein homeostasis. Cell. 2013;152:196–209.

Hohenblum H, Gasser B, Maurer M, Borth N, Mattanovich D. Effects of gene dosage, promoters, and substrates on unfolded protein stress of recombinant Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;85:367–75.

Zhang W, Zhao H, Xue C, Xiong X, Yao X, Li X, Chen H, Liu Z. Enhanced secretion of heterologous proteins in Pichia pastoris following overexpression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chaperone proteins. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:1090–5.

Ahmad M, Hirz M, Pichler H, Schwab H. Protein expression in Pichia pastoris: recent achievements and perspectives for heterologous protein production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:5301–17.

Kerner MJ, Naylor DJ, Ishihama Y, Maier T, Chang HC, Stines AP, Georgopoulos C, Frishman D, Hayer-Hartl M, Mann M, Hartl FU. Proteome-wide analysis of chaperonin-dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2005;122:209–20.

Lian X, Guo J, Gu W, Cui Y, Zhong J, Jin J, He QY, Wang T, Zhang G. Genome-wide and experimental resolution of relative translation elongation speed at individual gene level in human cells. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005901.

Sharp PM, Li W-H. The codon adaptation index-a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1281–95.

Akcapinar GB, Gul O, Sezerman U. Effect of codon optimization on the expression of Trichoderma reesei endoglucanase 1 in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Prog. 2011;27:1257–63.

Yu CH, Dang Y, Zhou Z, Wu C, Zhao F, Sachs MS, Liu Y. codon usage influences the local rate of translation elongation to regulate co-translational protein folding. Mol Cell. 2015;59:744–54.

Chu D, Kazana E, Bellanger N, Singh T, Tuite MF, von der Haar T. Translation elongation can control translation initiation on eukaryotic mRNAs. EMBO J. 2014;33:21–34.

Jin Z, Han SY, Zhang L, Zheng SP, Wang Y, Lin Y. Combined utilization of lipase-displaying Pichia pastoris whole-cell biocatalysts to improve biodiesel production in co-solvent media. Bioresour Technol. 2013;130:102–9.

Huang J, Xia J, Yang Z, Guan F, Cui D, Guan G, Jiang W, Li Y. Improved production of a recombinant Rhizomucor miehei lipase expressed in Pichia pastoris and its application for conversion of microalgae oil to biodiesel. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:111.

Siripong W, Wolf P, Kusumoputri TP, Downes JJ, Kocharin K, Tanapongpipat S, Runguphan W. Metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris for production of isobutanol and isobutyl acetate. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:1.

Huard FP, Deane CM, Wood GR. Modelling sequential protein folding under kinetic control. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:e203–10.

Komar AA. A pause for thought along the co-translational folding pathway. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:16–24.

Ellis JJ, Huard FPE, Deane CM, Srivastava S, Wood GR. Directionality in protein fold prediction. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:172.

Li C, Lin Y, Zheng X, Pang N, Liao X, Liu X, Huang Y, Liang S. Combined strategies for improving expression of Citrobacter amalonaticus phytase in Pichia pastoris. BMC Biotechnol. 2015;15:88.

Pan R, Zhang J, Shen WL, Tao ZQ, Li SP, Yan X. Sequential deletion of Pichia pastoris genes by a self-excisable cassette. FEMS Yeast Res. 2011;11:292–8.

Kiseleva E, Allen TD, Rutherford SA, Murray S, Morozova K, Gardiner F, Goldberg MW, Drummond SP. A protocol for isolation and visualization of yeast nuclei by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1943–53.

Wang T, Cui Y, Jin J, Guo J, Wang G, Yin X, He QY, Zhang G. Translating mRNAs strongly correlate to proteins in a multivariate manner and their translation ratios are phenotype specific. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4743–54.

Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5:621–8.

Bloom JS, Khan Z, Kruglyak L, Singh M, Caudy AA. Measuring differential gene expression by short read sequencing: quantitative comparison to 2-channel gene expression microarrays. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:221.

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2009;26:139–40.

MacKay VL, Li XH, Flory MR, Turcott E, Law GL, Serikawa KA, Xu XL, Lee H, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, et al. Gene expression analyzed by high-resolution state array analysis and quantitative proteomics—response of yeast to mating pheromone. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:478–89.

Hanebuth MA, Kityk R, Fries SJ, Jain A, Kriel A, Albanese V, Frickey T, Peter C, Mayer MP, Frydman J, Deuerling E. Multivalent contacts of the Hsp70 Ssb contribute to its architecture on ribosomes and nascent chain interaction. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13695.

Authors’ contributions

YL, GZ, SL and MG conceived and designed the project. XL, JZ, RX and LL performed the experiments. XL, JZ and CL analyzed the results. JJ contributed to the reagents and materials. XL wrote the manuscript, and YL and GZ revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof Yonghua Wang (South China University of Technology), Prof Shaochun Yuan and Dr. Liutao Chen (Sun Yat-sen University) for experimental support of polysome profiles.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The raw sequencing data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus database (Accession Number GSE116415), (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE116415).

Consent for publication

All authors approved to publish to article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2017YFA0505001/2018YFC0910200) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31470159).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Predicted ribosomal protein genes of P. pastoris GS115.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Ribosomal protein gene paralogs in P. pastoris GS115. Table S3. Gene copy numbers of eGFP and Phy in P. pastoris GS115 genome detected by real-time qPCR. Table S4. Two-way ANOVA on three biological replicates of the assay of Phy nascent chains co-translational folding efficiency. Figure S1. Confirmation of the deletants by PCR. After methanol induction, single colonies were isolated by streak plate method. Deletants were subject to PCR analysis using two outer primers (e.g., REI1-KO-S and REI1-KO-A), both of which were located outside of the homologous region. An expected deleted fragment could be amplified from deletants using the wide type strains as control. The gene size of RPGs and 60 processing factors is as follows: rpl22 (390 bp), rpl24 (477 bp), rpl26 (384 bp), rpl29 (180 bp), rpl38 (237 bp), rpl39 (156 bp), rpp1a (321 bp), rpp1b (324 bp), rpp1 (321/324 bp), rpl2a (765 bp), rpl2b (825 bp), rpl6a (543 bp), rpl6b (504 bp), rpl8a (753 bp), rpl8b (872 bp), rpl9a (576 bp), rpl9b (576 bp), rps7 (567 bp), rps25 (327 bp), rps6a (717 bp), rps22a (393 bp), rps22b (686 bp), rps27a (579 bp), rps27b (249 bp), rps28a (204 bp), rps28b (204 bp), asc1 (1286 bp), nop12 (1338 bp), rei1 (1224 bp). Figure S2. SDS-PAGE analysis of Phy expression with the collected culture supernatant in RPG deletion strains relative to wild-type at 120 h induction time. The molecular weight (MW) of glycosylated Phy is approximately 55 kDa. Figure S3. Expression analysis of two heterologous proteins in four RP deletion strains and wild-type. a SDS-PAGE analysis of Phy expression with the collected culture supernatant in rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rps7∆, rps25∆ strains relative to wild-type at 120 h induction time. b Phy expression profiles (activity per ml culture) of rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rps7∆, rps25∆ strains relative to the wild-type strain. c, d eGFP expression profiles and growth curve of rpl38∆, rpl9a∆, rps7∆, rps25∆ strains in relation to wild-type strain. Figure S4. RP complementation assay with eGFP and Phy expression profiles in RP deletion strains relative to wild-type. a, b eGFP expression profiles and growth curve. c, d Phy expression profiles and growth curve. The RPL38, RPL9A, RPS7, RPS25 gene were amplified by PCR using the primers shown as (Additional file 3: Table S5) from P. pastoris GS115 genome. Seamless Assembly Cloning Kit (C5891-25, CloneSmarter, USA) was used to clone these genes into the pGAPZA plasmid. The GAP-RP cassettes were amplified by the specific primers to assemble into the pPICZαA-eGFP and pPICZαA-Phy plasmid, respectively. Then RP deletion strains were transformed with the MssI-linearized expression cassettes to yield RP-complemented strains. Figure S5. Phy expression profiles of the 60S processing factor deletion strains relative to the wild-type strain. a SDS-PAGE analysis of the collected culture supernatant at 120 h induction time. b Activity per ml culture. Figure S6. Validation of the method used in isolation of protein aggregates. a BSA removal assay. Aggregated protein extraction was performed with total protein and total protein mixed with 10% BSA, separately. SDS-PAGE assay was carried out to visualize the protein band. The first lane was loaded with pure BSA as positive control and the other lane with the dashed boxes indicated the bands of approximate MW of BSA. b Quantitative analysis of BSA removal efficiency. The BSA optical density ratios were revealed through normalizing the optical density values of the bands with known BSA additions to those without BSA additions. Figure S7. Semi-quantitative analysis of ribosomal RNA in rps7∆ strain and wild-type. After methanol induction for 12 h, total RNA was extracted with the same OD600 of rps7∆ strain and wt. The concentrations of total RNA of the replicate 1: 749 ng µl−1 (wt), 1049 ng µl−1 (rps7∆), and the replicate 2: 738 ng µl−1 (wt), 1209 ng µl−1 (rps7∆) were measured using a Nano-drop spectrophotometer. Finally, the same volume of the sample was analyzed by 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Additional file 3: Table S5.

Primers used in this study.

Additional file 4: Table S6.

mRNA fold-change (log2) for chaperone genes. Table S7. RNC-mRNA fold-change (log2) for chaperone genes. P-values of differential expression were calculated using edgeR software.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, X., Zhao, J., Liang, S. et al. Enhancing co-translational folding of heterologous protein by deleting non-essential ribosomal proteins in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Biofuels 12, 38 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1377-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1377-z