Abstract

Background

Since the concept of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm (ITPN) was introduced in the current World Health Organization classification of tumors, the number of reports of ITPN occurrence has increased gradually. However, ITPN is usually located in the main pancreatic duct, with few reports of a branch duct ITPN. As a result, imaging protocols for the diagnosis of a branch duct ITPN have not been established.

Case presentation

We report a case of a concurrent presentation of a branch duct ITPN and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) in the head of the pancreas, with a superior mesenteric artery (SMA) aneurysm. Initially, the cystic masses in the pancreatic head were diagnosed as branch duct IPMNs, with treatment consisting of a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, in combination with an aneurysmectomy performed for treatment of the SMA aneurysm. Pathological examination confirmed these cysts were a combination of branch-type ITPN and IPMN. The patient recovered from the treatment without complication, with no evidence of recurrence over a period of 34 months post-surgery.

Conclusion

This case report of a synchronous presentation of an ITPN and IPMN indicates the difficulty in differentiating these two types of neoplasms in the branch duct of the pancreatic head.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cystic lesions in the pancreas have been identified with increasing frequency in recent years due to the development and advancement of imaging technology. Although some of these cystic tumors, such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), have a potential for malignancy that cannot be ignored, considering the risks associated with pancreatic resection, surgical treatment must be considered with caution. Therefore, accurate imaging is clinically important to establish a diagnosis and indication for surgery.

Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms (ITPNs) were introduced as a new type of pancreatic tumor by Yamaguchi et al. in 2009 [1] and subsequently included as an independent entity in the current World Health Organization classification of tumors in 2010. ITPNs show a predominantly tubular growth pattern, with a papillary component and absence of intracytoplasmic mucin [2]. These features differentiate ITPN from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMNs) and pancreatic intra-epithelial neoplasia. Although the clinical course of ITPN has been reported to be indolent, with a better prognosis than for invasive ductal adenocarcinoma [1, 3, 4], an ITPN may have invasive features and can metastasize to lymph nodes or the liver [1]. While the number of case reports on ITPNs is limited, the report of an ITPN in a branch duct of the pancreas is even rarer as these tumors are usually located in the main pancreatic duct. Therefore, image findings for ITPN diagnosis and surgical indication remain unclear.

An aneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is also a rare occurrence, accounting for only 6.9% of all visceral artery aneurysms [5], and carries the risk for embolism or rupture, with subsequent mesenteric ischemia and massive hemorrhage [6]. Surgical intervention is recommended to prevent these fatal complications [5, 6]. Although endovascular treatment can be effective for the treatment of a SMA aneurysms, open surgery, including aneurysmectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy, may be required depending on the characteristics of the aneurysm [5,6,7]. In this case report, we describe the presentation and clinical diagnosis of a patient with a rare occurrence of a concurrent presentation of branch duct ITPN and IPMN in the pancreatic head, with a SMA aneurysm.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old woman presented to a local hospital complaining of epigastralgia and anemia. Endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract revealed gastritis, with pancreatic masses observed on abdominal ultrasonography. Computed tomography (CT) imaging further revealed an aneurysm of the SMA. Based on these findings, the patient was admitted to our hospital for further investigation and treatment.

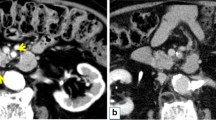

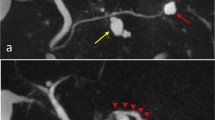

Her medical history included hypertension, cerebral hemorrhage, and panic disorder, with no indication of hyperglycemia. Findings on physical examination were unremarkable and laboratory data, including tumor markers, were within normal limits. Dynamic CT imaging revealed a saccular SMA aneurysm, with a 2.4-cm diameter, located 2 cm distal to the origin of the SMA (Fig. 1a–c), as well as a multiloculated cystic mass in the pancreatic head, with no mural nodule on enhanced CT imaging (Fig. 2a, b). Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging confirmed the cystic masses in the pancreatic head (Fig. 2c), but with no indication of dilation of the main pancreatic duct on MR cholangiopancreatography (Fig. 2d). Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a 5-cm hypoechoic area in the pancreatic head, but with no evidence of a mural nodule and dilation of the main pancreatic duct upstream, in the distal pancreas (Fig. 2e, f). Based on these findings, a preoperative clinical diagnosis of branch duct IPMN, with a concurrent SMA aneurysm, was made, with a serous cystic neoplasm and pseudocyst included in the differential diagnosis.

Axial (a) and coronal (b) contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing a cystic mass in the pancreatic head. Fat-suppressed T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (c) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (d), showing a 50 × 33-mm cystic mass, without dilation of the main pancreatic duct. Endoscopic ultrasound image, showing a 50-mm hypoechoic area in the pancreatic head (e). Mural nodules and dilation of the main pancreatic duct upstream, in the distal pancreas, were not observed (f)

After obtaining informed consent, we simultaneously performed a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy and SMA aneurysmectomy. Macroscopic examination revealed the presence of two cystic masses in the pancreatic head. Neoplastic cells were identified in one of these masses, characterized by enlarged nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm containing little mucus (Fig. 3a–c). The other cystic mass showed a proliferation of low-papillary columnar cells, with intracellular mucus (Fig. 3d–f). Immunohistochemical examination revealed positive staining of the mucin-poor region of the first cystic mass for MUC-1, MUC-6, and CDX-2, but negative for MUC-2 and MUC-5 AC (Fig. 4a–e), with an approximate Ki-67 index in this region of 1%. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of ITPN was confirmed. For the second cystic mass, the mucin-rich region stained positive for MUC-5 AC and MUC-6, but negative for CDX-2, MUC-1, and MUC-2 (Fig. 4f–j), with an approximate Ki-67 index in this region of < 1%. Based on these results, this mass was diagnosed as an intraductal papillary mucinous adenoma with moderate atypia. The final histologic diagnosis for the first mass was an ITPN, with high-grade dysplasia, and branch duct-type IPMN, with moderate atypia, for the second mass. There was no evidence of malignancy or lymph node metastasis.

Macroscopic assessment revealed one of the two cystic masses to be an intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm (ITPN; arrow) and the other an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN; arrowhead) (a, d). Features of the ITPN included neoplastic cells with enlarged nuclei, with the eosinophilic cytoplasm contains little mucus (b, c). In contrast, the IPMN showed neoplastic cells, with obvious mucin in well-developed tubules (e, f)

Representative micrographs of the intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm (ITPN; a–e) and the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN; f–j) specimens, immunostained for CDX-2 (a, f), MUC-1 (b, g), MUC-2 (c, h), MUC-5 AC (d, i), and MUC-6 (e, j). ITPN stained positive for CDX-2 (a), MUC-1 (b), and MUC-6 (e), and negative for MUC-2 (c) and MUC-5 AC (d). IPMN stained positive for MUC-5 AC (i) and MUC-6 (j), and negative for CDX-2 (f), MUC-1 (g), and MUC-2 (h)

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful and her length of hospital stay was 35 days. She has remained symptom-free since treatment, with no recurrence of the neoplasm over the 34-month follow-up.

Discussion and conclusions

It has been reported that ITPN accounts for only 0.9% of all pancreatic exocrine tumors and 3% of all pancreatic intraductal neoplasms [1]. Although the pathological definition of ITPNs has been established, because of their rarity, their clinical and imaging features for diagnosis have not been clearly defined. Several studies have suggested that preoperative diagnosis of intraductal tubular neoplasms to be difficult [8,9,10,11]. With specific regard to the diagnosis of an ITPN, Oh et al. [11] and Ishigami et al. [10] suggested that upstream dilation of the main pancreatic duct may be a specific finding to differentiate an ITPN from an IPMN. Ishigami et al. reported three cases of intraductal tubular neoplasms that were hypovascular tumors without downstream pancreatic duct dilation on CT and MR imaging [10]. Furthermore, Motosugi et al. described the “2-tone duct sign” and “cork-of-wine-bottle sign” as characteristic findings of ITPNs on diagnostic imaging [12]. However, these features are specific to neoplasms of the main pancreatic duct, which is the most common site for pancreatic ITPNs, with reports of branch duct ITPNs being very limited. Yoshida et al. reported an ITPN of the pancreatic branch duct which presented as a round, well-circumscribed, weakly enhanced hypovascular mass [13]. In our case, the cystic masses did not demonstrate typical findings of a main duct ITPN, with their features, in fact, being more consistent of a branch duct ITPN or IPMN. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or transpapillary biopsy was not performed in our case as the IPMN was located in a branch duct, some reports have demonstrated that transpapillary biopsy or brush may be useful for preoperative diagnosis [2, 8].

Initially, we had diagnosed the two cystic masses as IPMNs. According to the international consensus guidelines for the management of IPMNs (2012), immediate resection is not indicated (although the decision should be made on a case-by-case basis) for branch duct IPMNs with a diameter > 3 cm and without observable mural nodules [14]. In the present case, the cyst was approximately 5 cm in diameter and there were no other risk factors, such as mural nodule or positive cytology. We considered a pancreaticoduodenectomy to be an appropriate treatment based on the characteristics of the IPMNs, while also taking into consideration the patient’s symptoms, surgical risk, the patient’s relatively young age, and absence of comorbidities, as well as the presence of a SMA aneurysm.

Histologic examination of the two cystic tumors identified on preoperative imaging confirmed the presence of two types of neoplasms, namely an ITPN and an IPMN. Yamaguchi et al. described the pathological characteristics of an ITPN as follows: (1) a solid nodular tumor obstructing dilated ducts on macroscopic examination, (2) no visible secretion of mucin, (3) tubulopapillary growth, (4) uniform high-grade atypia throughout the neoplasm, (5) an easily recognizable necrotic foci, (6) ductal differentiation, and (7) absence of acinar differentiation [1]. Immunohistochemical staining is useful to confirm the ITPN, with MUC-1, MUC-6, and CDX-2 tend to be expressed, with negative staining for MUC-2 and MUC-5 AC [1]. In our case, the neoplasm presented a tubulopapillary growth pattern, without visible mucin secretion and positive immunohistochemical staining for MUC-1, MUC-6, and CDX-2, and negative results for MUC-2 and MUC-5 AC confirmed the diagnosis. For the second cyst, positive results for MUC-5 AC and MUC-6, and negative results for MUC-1, MUC-2, and CDX-2 were consistent with a diagnosis of IPMN [15].

In general, the prognosis for ITPNs is considered to be much better than the poor prognosis for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [1, 16]. The largest published case series to date reported on the outcomes of 10 cases of ITPNs, three of which had stromal invasion extending to the veins, bile ducts, and duodenum [1]. Among these cases, one patient died of multiple liver metastases from the neoplasm at 7 months after primary resection. In the remaining cases, there was no evidence of metastasis to the regional lymph nodes, with all patients being still alive up to 7 years after diagnosis. It has been suggested that the Ki-67 labeling index may be predictive of the prognosis [1]. In our case, the patient was still alive 34 months after diagnosis and treatment, with no evidence of recurrence.

With respect to SMA aneurysms, surgical interventions including pancreatic resection and stent-grafting are recommended treatments due to the risk of rupture [5]. In our case, as the aneurysm was relatively close to the origin of the SMA and first jejunal artery and had a wide neck, we selected to proceed with open surgery over stent-grafting or simple coil embolization. Pancreaticoduodenectomy was theoretically a suitable procedure as the aneurysm was located just behind the pancreas, and fortunately, the cystic tumor in the pancreatic head could be resected at the same time.

We identified 44 articles published in English addressing ITPN in PubMed using the keywords “ITPN” and “intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm,” as well as four Japanese articles from other sources. Eight articles addressing ITPN in the bile duct were excluded, while another 10 articles were excluded because they did not provide detailed patient data. Therefore, we extracted comprehensive data on 51 cases of ITPN from 26 articles [1,2,3,4, 12, 13, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Among these cases, only six cases (11.8%) arose from the branch duct. In addition, there was no report mentioning an association between ITPN and IPMN.

Therefore, our case of a concurrent branch duct ITPN and IPMN in the pancreatic head, with a SMA aneurysm, is a very rare occurrence, with an association between an ITPN and IPMN not previously having been reported. Our case underlines the difficulty in differentiating these two types of neoplasm pre-operatively. Therefore, an ITPN should be included in the differential diagnosis, even when a cystic mass suggestive on an IPMN is observed.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

- ITPN:

-

Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- SMA:

-

Superior mesenteric artery

References

Yamaguchi H, Shimizu M, Ban S, Koyama I, Hatori T, Fujita I, et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas distinct from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1164–72.

Kasugai H, Tajiri T, Takehara Y, Mukai S, Tanaka J, Kudo SE. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. J Nippon Med Sch. 2013;80:224–9.

Jokoji R, Tsuji H, Tsujimoto M, Shinno N, Tori M. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of pancreas with stromal osseous and cartilaginous metaplasia: a case report. Pathol Int. 2012;62:339–43.

Furuhata A, Minamiguchi S, Mikami Y, Kodama Y, Sumiyoshi S, Adachi S, et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm with expansile invasive carcinoma of the pancreas diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:314–20.

Stone WM, Abbas M, Cherry KJ, Fowl RJ, Gloviczki P. Superior mesenteric artery aneurysms: is presence an indication for intervention? J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:234–7. discussion 237

Jiang J, Ding X, Su Q, Zhang G, Wang Q, Jian W, et al. Therapeutic management of superior mesenteric artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1619–24.

Suzuki K, Mori Y, Komada T, Matsushima M, Ota T, Naganawa S. Stent-graft treatment for bleeding superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:762–6.

Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Kimura K, Horaguchi J, et al. Intraductal tubular adenocarcinoma of the pancreas diagnosed before surgery by transpapillary biopsy: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:325–9.

Itatsu K, Sano T, Hiraoka N, Ojima H, Takahashi Y, Sakamoto Y, et al. Intraductal tubular carcinoma in an adenoma of the main pancreatic duct of the pancreas head. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:702–5.

Ishigami K, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Shinozaki K, Nagata S, Yamaguchi K, et al. Imaging of intraductal tubular tumors of the pancreas. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1836–40.

Oh DK, Kim SH, Choi SH, Jang KT. Intraductal tubular carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report with the imaging findings. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:473–6.

Motosugi U, Yamaguchi H, Furukawa T, Ichikawa T, Hatori T, Fujita I, et al. Imaging studies of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: 2-tone duct sign and cork-of-wine-bottle sign as indicators of intraductal tumor growth. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36:710–7.

Yoshida Y, Matsubayashi H, Sasaki K, Kanemoto H, Uesaka K, Ono H. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreatic branch duct showing atypical images. J Dig Dis. 2015;16:357–61.

Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–97.

Ban S, Naitoh Y, Mino-Kenudson M, Sakurai T, Kuroda M, Koyama I, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas: its histopathologic difference between 2 major types. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1561–9.

Tajiri T, Tate G, Inagaki T, Kunimura T, Inoue K, Mitsuya T, Yoshiba M, et al. Intraductal tubular neoplasms of the pancreas: histogenesis and differentiation. Pancreas. 2005;30:115–21.

Bhuva N, Wasan H, Spalding D, Stamp G, Harrison M. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas as a radiation induced malignancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2011; Dec 2011:doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.09.2011.4777.

Yamaguchi H, Kuboki Y, Hatori T, Yamamoto M, Shiratori K, Kawamura S, et al. Somatic mutations in PIK3CA and activation of AKT in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1812–7.

Tajiri T, Tate G, Matsumoto K, Hoshino H, Iwamura T, Kodaira Y, et al. Diagnostic challenge: intraductal neoplasms of the pancreatobiliary system. Pathol Res Pract. 2012;208:691–6.

Urata T, Naito Y, Nagamine M, Izumi Y, Tonaki G, Iwasaki H, et al. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas with somatic BRAF mutation. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2012;5:413–20.

Ahls MG, Niedergethmann M, Dinter D, Sauer C, Luttges J, Post S, et al. Case report: intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas with unique clear cell phenotype. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:11.

Del Chiaro M, Mucelli RP, Blomberg J, Segersvard R, Verbeke CI. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasia a new entity in the spectrum of familial pancreatic cancer syndrome? Familial Cancer. 2014;13:227–9.

Guan H, Gurda G, Lennon AM, Hruban RH, Erozan YS. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas on fine needle aspiration: case report with differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:156–60.

Someya Y, Nakamoto Y, Nakatani K, Kawaguchi M, Minamiguchi S, Togashi K. 18F-FDG uptake in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:e277–80.

Zhao L, Hart J, Xiao SY, Antic T. Cytological features of pancreatic intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm and an unexpected immunohistochemical profile. Pathology. 2014;46:662–5.

Kitaguchi K, Kato Y, Kojima M, Okubo S, Takahashi D, Okada R, et al. A resected case of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: report of a case. Int Surg. 2015;100:281–6.

Kolby D, Thilen J, Andersson R, Sasor A, Ansari D. Multifocal intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas with total pancreatectomy: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:9672–80.

Matthews Y, McKenzie C, Byrne C, Kench JG. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of pancreas with associated invasive carcinoma, lymph node, rectal and hepatic metastases. Pathology. 2015;47:169–71.

Muraki T, Uehara T, Sano K, Oota H, Yoshizawa A, Asaka S, et al. A case of MUC5AC-positive intraductal neoplasm of the pancreas classified as an intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm? Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:1034–9.

Tajima S. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas suspected by endoscopic ultrasonography-fine-needle aspiration cytology: report of a case confirmed by surgical specimen histology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:1003–6.

Takayama S, Maeda T, Nishihara M, Kanazawa A, Chong HS, Oka H, et al. A case of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of pancreas with severe calcification, a potential pitfall in diagnostic imaging. Pathol Int. 2015;65:501–6.

Date K, Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Iwata J, Sumiyoshi T, Kozuki A, et al. Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a systematic review. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2016;401:439–47.

Savant D, Lee L, Das K. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas masquerading as pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: review of the literature with a case report. Acta Cytol. 2016;60:267–74.

Fujimoto Y, Tomimaru Y, Tamura H, Noguchi K, Nagase H, Hamabe A, et al. Pancreatic intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm with associated invasive cancer successfully treated by total pancreatectomy: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:153–8.

Kovacevic B, Latorre Ano P, Toxvaerd A, Vilmann P, Kalaizakis E. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2017;49:E266–7.

Niu L, Xu Z, Liu H, Cao H, Yang G. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm accompanied by invasive carcinoma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:676–82.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no funding.

Availability of data and materials

All the data of case report are included in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KI wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. MK participated in the operation and supervised the writing of the paper. HO participated in the operation and revised the manuscript critically. Y-NF and MS prepared the pathological findings. MS, HY, YA, TH, KM, GO, OI, and YK critically reviewed the manuscript. YS and MI participated in the surgery. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Keio University. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the case report and accompanying images.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Inomata, K., Kitago, M., Obara, H. et al. Concurrent presentation of an intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in the branch duct of the pancreas, with a superior mesenteric artery aneurysm: a case report. World J Surg Onc 16, 83 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1391-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1391-9