Abstract

Background

The prevalence of obesity in U.S. has been rising at an alarming rate,particularly among Hispanic, African, and Asian minority groups. This trendis due in part to excessive calorie consumption and sedentary lifestyle. Wesought to investigate whether parental origins influence eating behaviors inhealthy urban middle school students.

Methods

A multiethnic/racial population of students (N = 182) enrolled inthe ROAD (Reduce Obesity and Diabetes) Study, a school-based trial to assessclinical, behavioral, and biochemical risk factors for adiposity and itsco-morbidities completed questionnaires regarding parental origins, lengthof US residency, and food behaviors and preferences. The primary behavioralquestionnaire outcome variables were nutrition knowledge, attitude,intention and behavior, which were then related to anthropometric measuresof waist circumference, BMI z-scores, and percent body fat. Two-way analysisof variance was used to evaluate the joint effects of number of parents bornin the U.S. and ethnicity on food preference and knowledge score. TheTukey-Kramer method was used to compute pairwise comparisons to determinewhere differences lie. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyzethe joint effects of number of parents born in the US and student ethnicity,along with the interaction term, on each adiposity measure outcome. Pearsoncorrelation coefficients were used to examine the relationships betweenmaternal and paternal length of residency in the US with measures ofadiposity, food preference and food knowledge.

Results

African Americans had significantly higher BMI, waist circumference and bodyfat percentage compared to other racial and ethnic groups. Neitherethnicity/race nor parental origins had an impact on nutrition behavior.Mothers’ length of US residency positively correlated withstudents’ nutrition knowledge, but not food attitude, intention orbehavior.

Conclusions

Adiposity measures in children differ according to ethnicity and race. Incontrast, food behaviors in this middle school sample were not influenced byparental origins. Longer maternal US residency benefited offspring in termsof nutrition knowledge only. We suggest that interventions to preventobesity begin in early childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The increasing prevalence of obesity in the U.S. and elsewhere has led to a sharprise in the rate of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in adolescents over the last20 years according to the NHANES [1]. This is likely due to multiple factors such as poor diet and/or moresedentary lifestyle. The increase in obesity has been most prominently observed inminority groups such as Native-, Asian-, African-, and Hispanic-Americans [2]. This might be attributable to greater poverty among these groups andgenetic/ethnic predisposition [3]. Additional factors include westernization of diet tocalorie-dense/low-fiber foods seen with migration, as well as adoption of sedentarylifestyles [4].

There has been an increasing call for prevention in preference to treatmentinterventions [5]. Once obesity is established, it is difficult to reverse throughinterventions [6] and it often persists through adulthood, especially if present inperipubertal period or later [7], strengthening the case for early primary prevention. Schools provide acaptive audience for such initiatives [8]. Some school-based research studies have focused on interventions inoverweight children, primarily through the use of specialized health facilities andafter school tutorials [9, 10], while others have targeted the whole school population (reviewed in [11]).

Previous studies of Mexican-American adults suggest that diet quality decreases withduration of residence in the United States. Specifically, consumption of fiber,fruit, and vegetables decreases with duration of residence in the United States,whereas consumption of processed foods, refined carbohydrates, and sugars increases [12]. In light of the above we sought to investigate the influence of parentalorigins on eating behaviors in a multi-ethnic/racial population of urban middleschool students.

Subjects and methods

The ROAD (Reduce Obesity and Diabetes) Study, a 5-year randomized study, wasconducted by a research consortium (Columbia University Medical Center,Maimonides Infants and Children’s Hospital, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine,Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York, and Winthrop UniversityHospital) that was coordinated through AMDeC (Academy for Medical Developmentand Collaboration, New York, NY, USA). The ROAD Study examined the prevalence ofpre-diabetic phenotypes and the effects of supervised exercise/nutritioneducation on clinical (adiposity), biochemical (inflammation, lipids, glucosehomeostasis) and behavioral risk factors for type 2 DM in a multi-ethnic/racialpopulation of 6th-8th grade students before and after participating in a14 week school-based health, nutrition, and exercise intervention [13]. Detailed methods for this study have been described elsewhere [8]. The primary objective of our sub-study was to determine howparents’ country of origin, length of residency in the USA, andethnicity/race affect measures of adiposity and nutrition at baseline. Thequestionnaires were administered in the first year of student participation inthe study, without the benefit of an intervention aimed at improvingstudents’ nutrition and fitness. Because recruitment was not synchronousacross all sites, not all subjects were queried about parental origins andlength of US residency. The school where most of subjects were recruited waslocated in Queens, in a heavily Asian area. The primary outcome variables werenutrition knowledge, attitude, intention and behavior, as well as measures ofadiposity, specifically, waist circumference z-scores, BMI z-scores, and percentbody fat. BMI and waist circumferences were collected at the initial studyvisit, Z-scores were calculated for BMI using Epi Info (TM) [14], and waist circumference according to Fernandez et.al [15].

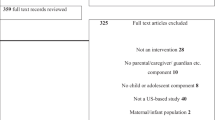

Data on parental origin and length of residency in the United States werecollected as part of the intake information for each student at their start datein the study. Student nutrition knowledge and dietary behaviors were assessedusing modified Hearts N'Parks subscales. Hearts N’Parks is a national,community-based program supported by the National Heart, Lung, and BloodInstitute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health and the NationalRecreation and Park Association (NRPA) [16]. It assesses the student on varied aspects of nutrition, includingknowledge (with a maximum score 12 points), behavior (40 points), intention (8points), and attitudes (7 points). There were a total of 794 middle school-agesubjects studied at baseline in the 5 middle schools. Data regarding country oforigin data were limited, as this information was not collected from the startin every school. Therefore, 599 subjects had missing country of origin data forone or both parents. Thirteen additional students were missing ethnicity.Therefore, the final sample size in this sub-study was 182 subjects.

The average age was 12.4 years ± 1.0 and more than half ofthe students were female (60.4%). A plurality of students were of East Asianorigin (31.3%). The remaining 68.7% included African American students (14.8%),Caucasians (13.2%), Hispanic (19.2%), South Asian (18.1%) and a small percentageof students identified as “Other” (3.3%).

There were 123 (67.6%) subjects with neither parent born in the US, 17 (9.3%)subjects with one parent born in the US and 42 (23.1%) subjects with bothparents born in the US.

Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with an interaction term was used to analyzethe joint effects of number of parents born in the US and student ethnicity oneach food preference and knowledge score outcome. If the interaction term wasnon-significant it was removed from the model. The Tukey-Kramer method was usedto compute pairwise comparisons to determine where differences lie.

Additionally, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze the jointeffects of number of parents born in the US and student ethnicity, along withthe interaction term, on each adiposity measure outcome. If the interaction termwas non-significant it was removed from the model. Although not of directinterest, age and gender were considered to be potential confounders ofadiposity measures and were therefore included as covariates. The Tukey-Kramermethod was used to compute pairwise comparisons to determine where differenceslie.

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationships betweenmaternal and paternal length of residency in the US with measures of adiposity,food preference and food knowledge.

All statistical analysis was conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary,NC).

Results

Waist Z-score

African American students had significantly higher waist z-scores(Table 1) as compared to Caucasian students(P < 0.007), East Asian students (P < 0.0001), andSouth Asian students (P < 0.001). Hispanic students hadsignificantly higher waist z-scores as compared to East Asian students(P < 0.0001) and South Asian students (P < 0.01).There was no significant association between number of parents born in the USand waist z-score (P < 0.90). The interaction term between numberof parents born in the US and ethnicity was not significant and removed from thefinal model.

BMI Z-score

The main effect of ethnicity was a significant association with BMI z-score(Table 1, P < 0.009).Specifically, African American students had significantly higher BMI z-scores ascompared to East Asian students (P < 0.007) and South Asianstudents (P < 0.03). There were no other significantassociations.

There was no significant association between number of parents born in the US andBMI z-score (P < 0.5). The interaction term between number ofparents born in the US and ethnicity was not significant and removed from thefinal model.

Percent body fat

The main effect of ethnicity was significantly associated with percent body fat(Table 1, P < 0.001).Specifically, African American students had significantly higher percent bodyfat as compared to East Asian students (P <0.03). However, this was notrelated to the number of parents born in the US (P < 0.5).

Nutrition knowledge

There were no significant associations between nutrition knowledge and number ofparents born in the US (P < 0.2) or ethnicity/race(P < 0.5) (Table 1).

Healthy eating attitude

There were no significant associations between healthy eating attitude and numberof parents born in the US (P < 0.4) and ethnicity/race(P < 0.5) (Table 1).

Healthy eating behavior

There were no significant associations between self-report of healthy eatingbehavior and number of parents born in the US (P < 0.3) andethnicity/race (P < 0.4) (Table 1).

Healthy eating intentions

There were no significant associations between healthy eating intentions andnumber of parents born in the US (P < 0.5) or ethnicity/race(P < 0.7) (Table 1).

Length of residency

There was a significant positive correlation between the mother’s length ofUS residency and nutrition knowledge (Table 2,p < 0.01). There was also a significant negative correlationbetween mother’s length of residency and healthy eating attitude(p < 0.02).

Discussion

The primary objective of this substudy was to determine if there were significantcorrelations of parental origins and ethnicity/race with children’s adipositymeasures (such as BMI, waist circumference, and body fat) as well as nutritionknowledge and food-related behaviors. With respect to adiposity measures, theAfrican American group in our population had a higher BMI, waist circumference andbody fat percentage, which is similar to recently published findings in our largerdata set [17]. Neither ethnicity/race nor parental origins had an impact on nutritionbehavior. Nutrition knowledge, but not attitude, improved with mothers’ lengthof residency. The positive association between maternal length of residency andnutrition knowledge is likely due to media exposure, friends and family, as well ashealth providers [18]. In many families, mothers are the primary food preparers in thehousehold [19]. A study by Variyam et al reported a significant positive relationshipbetween mothers’ nutrition knowledge and children’s diets; however, thisinfluence decreases as children grow older [20]. The disparity between nutrition knowledge and attitudes among middleschool students as related to length of mothers’ US residency highlights theeffect of rapid acculturation. Our data seem to agree with those from the NationalLongitudinal Study of Adolescent Health demonstrating rapid acculturation ofoverweight-related behaviors, including diet and inactivity among immigrant Hispanicadolescents [21].

As noted above, our study shows that African American adolescents, especiallyfemales, had significantly higher waist Z-scores, BMI Z-scores, and body fatpercentage in comparison with other racial and ethnic populations. These resultsconfirm previous studies that show disparities between ethnic groups with adipositymeasures [22, 23]. In addition, parental origins and length of residency did not have asignificant influence on our adolescents’ nutrition behavior. Again this maybe due to acculturation in early childhood. It has been shown that recentimmigration to the United States results in rapid loss of the dietary pattern fromparental country of origin [24]. It is also known that younger immigrants tend to change their diets toassimilate to their host country more readily than older ones [25]. As a result, there is a higher risk for obesity associated with lengthof residence in the United States due to adoption of suboptimal dietary behaviorsand sedentary lifestyles, as seen in studies with the Hispanic population [26].

The limitations of our study include the lack of information on parental adipositymeasures, as well as socioeconomic status. Parental BMI has been shown to affecttheir offspring’s dietary behavior as well as weight status [27]. Rates of obesity in most areas of the United States follow asocioeconomic gradient, such that the burden of disease falls disproportionately onpeople with limited resources, racial-ethnic minorities, and the poor [28].

Childhood obesity may increase adult morbidity and mortality independent of adult BMIand other confounding factors such as family history of cardiovascular diseases,cancer and smoking [29]. Therefore, it is imperative to strive for the prevention of childhoodobesity, rather than treat it after it is established or chronic. School-basedprograms, such as the ROAD Study, represent an appropriate setting for obesityintervention because they offer continuous and intensive contact with children.School infrastructure and physical environment, policies, curricula, and staff allhave the potential to positively influence knowledge and lifestyle [30]. Such programs have potential for long-lasting impact if delivered priorto the onset of obesity and its complications. The significance of our findings isthat there is rapid acculturation to western diet among adolescents, regardless ofparental origins. Our finding that the mother’s length of residency in the USAaffects the nutritional knowledge and attitudes of adolescents could influence theway in which we approach teaching young students about nutrition.

Conclusions

Our main findings are that direct and surrogate physical measurements of adiposity inchildren differ according to ethnicity and race. In contrast, food behaviors in thiscross-sectional middle school sample were not influenced by parental origins. Longermaternal US residency benefited offspring in terms of nutrition knowledge only. Wesuggest that interventions to prevent obesity begin in early childhood.

Abbreviations

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ROAD:

-

Reduce Obesity and Diabetes

- AMDeC:

-

Academy for MedicalDevelopment and Collaboration

- NHLBI:

-

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- NIH:

-

National Institutes of Health

- NRPA:

-

National Institutes of Health and theNational Recreation and Park Association

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- NYC:

-

New YorkCity.

References

Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, Nguyen M, Dietz WH: Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: findings fromthe third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003, 157: 821-10.1001/archpedi.157.8.821.

Dabelea D, Pettitt DJ, Jones KL, Arslanian SA: Type 2 diabetes mellitus in minority children and adolescents: an emergingproblem. Endocrinol Metab ClinNorthAm. 1999, 28: 709-729. 10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70098-0.

Speiser PW, Rudolf MC, Anhalt H, Camacho-Hubner C, Chiarelli F, Eliakim A, Freemark M, Gruters A, Hershkovitz E, Iughetti L: Childhood obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90: 1871-1887.

Misra A, Ganda OP: Migration and its impact on adiposity and type 2 diabetes. Nutrition. 2007, 23: 696-708. 10.1016/j.nut.2007.06.008.

Clarke J, Fletcher B, Lancashire E, Pallan M, Adab P: The views of stakeholders on the role of the primary school in preventingchildhood obesity: a qualitative systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013, 10.1111/obr.12058. [Epub ahead of print],

Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O'Malley C, Stolk RP, Summerbell CD: Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 21 (1): CD001872-

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH: Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997, 337: 869-873. 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301.

Rosenbaum M, Accacha SD, Altshuler LA, Carey DE, Fennoy I, Lowell BC, Rapaport R, Speiser PW, Shelov SP: The reduce obesity and diabetes (ROAD) project: design and methodologicalconsiderations. Child Obes. 2011, 7: 223-234.

Collins CE, Okely AD, Morgan PJ, Jones RA, Burrows TL, Cliff DP, Colyvas K, Warren JM, Steele JR, Baur LA: Parent diet modification, child activity, or both in obese children: anRCT. Pediatrics. 2011, 127: 619-627. 10.1542/peds.2010-1518.

Sacher PM, Kolotourou M, Chadwick PM, Cole TJ, Lawson MS, Lucas A, Singhal A: Randomized controlled trial of the MEND program: a family based communityintervention for childhood obesity. Obesity. 2010, 18: S62-S68. 10.1038/oby.2009.433.

Zenzen W, Kridli S: Integrative review of school-based childhood obesity prevention programs. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009, 23: 242-258. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2008.04.008.

Sofianou A, Fung TT, Tucker KL: Differences in diet pattern adherence by nativity and duration of USresidence in the Mexican-American population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011, 111: 1563-1569. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.07.005.

National Institutes of Health: Clinical Trials, Reduce, Obesity and Diabetes (ROAD).http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00954577,

Dean AG, Arner TG, Sunki GG, Friedman R, Lantinga M, Sangam S, Zubieta JC, Sullivan KM, Brendel KA, Gao Z: Epi InfoTM, a database and statistics program for public healthprofessionals. 2002, Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://wwwn.cdc.gov/epiinfo/ (accessed 10/16/13),

Fernandez JR, Redden DT, Pietrobelli A, Allison DB: Waist circumference percentiles in nationally representative samples ofAfrican-American, European-American, and Mexican-American children andadolescents. J Pediatr. 2004, 145: 439-444. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.044.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: Heart n’ Parks. [http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/obesity/hrt_n_pk/index.htm]

Rosenbaum M, Fennoy I, Accacha S, Altshuler L, Carey DE, Holleran S, Rapaport R, Shelov SP, Speiser PW, Ten S, Bhangoo A, Boucher-Berry C, Espinal Y, Gupta R, Hassoun AA, Iazetti L, Jean-Jacques F, Jean AM, Klein ML, Levine R, Lowell B, Michel L, Rosenfeld W: Racial/ethnic differences in clinical and biochemical type 2 diabetesmellitus risk factors in children. Obesity. 2013, 21: 2081-2090. 10.1002/oby.20483.

Perez - Escamilla R, Himmelgreen D, Bonello H, Gonzalez A, Haldeman L, Mendez I, Segura-Millan S: Nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among Latinos in the USA:influence of language. Ecol Food Nutr. 2001, 40: 321-345. 10.1080/03670244.2001.9991657.

Gualdi-Russo E, Manzon VS, Masotti S, Toselli S, Albertini A, Celenza F, Zaccagni L: Weight status and perception of body image in children: the effect ofmaternal immigrant status. Nutr J. 2012, 11: 1-9. 10.1186/1475-2891-11-1.

Variyam JN, Blaylock J, Lin BH, Ralston K, Smallwood D: Mother's nutrition knowledge and children's dietary intakes. Am J Agric Econ. 1999, 81: 373-384. 10.2307/1244588.

Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM: Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants tothe US: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Soc Sci Med. 2003, 57: 2023-2034. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00072-8.

Schuster MA, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Wallander JL, Tortolero SR, Ratner JA, Klein DJ, Cuccaro PM, Davies SL, Banspach SW: Racial and ethnic health disparities among fifth-graders in three cities. N Engl J Med. 2012, 367: 735-745. 10.1056/NEJMsa1114353.

Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM: Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children andadolescents, 1976–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011, 6: 12-20.

Batis C, Hernandez-Barrera L, Barquera S, Rivera JA, Popkin BM: Food acculturation drives dietary differences among Mexicans, MexicanAmericans, and non-Hispanic Whites. J Nutr. 2011, 141: 1898-1906. 10.3945/jn.111.141473.

Pan YL, Dixon Z, Himburg S, Huffman F: Asian students change their eating patterns after living in the UnitedStates. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999, 99: 54-57. 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00016-4.

Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Newsom JT, McFarland BH: The association between length of residence and obesity among Hispanicimmigrants. Am J Prev Med. 2004, 27: 323-326. 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.005.

Burke V, Beilin LJ, Dunbar D: Family lifestyle and parental body mass index as predictors of body massindex in Australian children: a longitudinal study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001, 25: 147-157. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801538.

Drewnowski A, Specter SE: Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 79: 6-16.

Must A, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, Bajema CJ, Dietz WH: Long-term morbidity and mortality of overweight adolescents: a follow-up ofthe Harvard Growth Study of 1922 to 1935. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327: 1350-1355. 10.1056/NEJM199211053271904.

Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK: Childhood obesity. Circulation. 2012, 126: 1770-1779. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047738.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lisa Rosen, PhD, Biostatistics Dept, The Feinstein Institute for MedicalResearch, North Shore LIJ Health System, and Dr. Patricia Vuguin for assistancewith statistical analysis and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RK, PWS, and MR helped to draft the manuscript. PWS, DC, SS, MR, SA, IF, RR, WR, STparticipated in the design of the study. DF, BC, AK, BL, and LA participated incollection and abstraction of data. All authors read and approved the finalmanuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuryan, R., Frankel, D., Cervoni, B. et al. Effects of parental origins and length of residency on adiposity measures andnutrition in urban middle school students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2013, 16 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2013-16

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2013-16