Abstract

The pure quadratic term of New Massive Gravity in three dimensions admits asymptotically locally flat, rotating black holes. These black holes are characterized by their mass and angular momentum, as well as by a hair of gravitational origin. As in the Myers–Perry solution in dimensions greater than five, there is no upper bound on the angular momentum. We show that, remarkably, the equation for a massless scalar field on this background can be solved in an analytic manner and that the quasinormal frequencies can be found in a closed form. The spectrum is obtained requiring ingoing boundary conditions at the horizon and an asymptotic behavior at spatial infinity that provides a well-defined action principle for the scalar probe. As the angular momentum of the black hole approaches zero, the imaginary part of the quasinormal frequencies tends to minus infinity, migrating to the north pole of the Riemann sphere and providing infinitely damped modes of high frequency. We show that this is consistent with the fact that the static black hole within this family does not admit quasinormal modes for a massless scalar probe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Three dimensional gravity has been a useful arena to explore gravitational models with simpler properties than their counterpart in four dimensions. Since the Weyl tensor identically vanishes in three dimensions, Einstein equations imply that the spacetime is locally flat or (A)dS depending on whether the theory has a null, negative or positive cosmological term, respectively. This implies that General Relativity has no local degrees of freedom in vacuum, but nevertheless in the case with a negative cosmological constant, its spectrum contains black holes (the BTZ black hole) [1]. These black holes have been of fundamental importance on the tests of the holographic correspondence between physics in Anti de Sitter spacetime and that of a dual Conformal Field Theory living at the boundary [2,3,4,5]. Just to mention two examples of this relation, the entropy of the BTZ black holes can be obtained by a microscopic counting of microstates in the dual theory [6] and their quasinormal ringing correlates precisely with relaxation time in the dual field theory at finite temperature [7, 8]. By the end of the last decade it was also realized that the lack of local degrees of freedom of General Relativity in three dimensions allows to construct a parity invariant, self-interacting theory for a massive particle of spin 2, i.e., a massive gravity theory. The Einstein-Hilbert Lagrangian is supplemented by quadratic terms in the curvature, and despite the fact that the field equations are of fourth order, their linearization around flat space correctly reproduces the Fierz–Pauli equation for a massive spin 2 excitation [9, 10]. The addition of a cosmological term allows to further explore the ideas of the holographic correspondence in the presence of a massive graviton in the bulk. As it generically occurs in theories containing quadratic powers in the curvature, such theory possesses two maximally symmetric (and therefore of constant curvature) solutions. For a precise relation of the couplings both vacua coincide and actually in this case one can find asymptotically locally (A)dS black holes that are characterized by the mass, angular momentum and an extra parameter that stands for a gravitational hair [12, 13]. As shown in [14] the entropy of such black holes can be reproduced by counting microstates in the boundary theory, providing a new test for such relation on a theory with local degrees of freedom in the bulk. Recently, there has been a revived interest in the study of asymptotic symmetries to null surfaces, where such surface could be null infinity or the event horizon of a black hole. It is expected that these studies might shed some light on the information paradox (see e.g. [15,16,17,18,19,20] and references therein). New Massive Gravity provides for a simple setup to carry on such studies, since the spectrum of the purely quadratic theory (that is healthy and intrinsically of fourth-order [10]) contains asymptotically locally flat, rotating black holes in 2 + 1 dimensions [12]. Such black holes do not exist in General Relativity in vacuum. Within the realm of NMG, these black holes can be generalized to construct non-circular black objects, dubbed black flowers [25], a family of metrics whose simplest representative is the rotating black hole constructed in [12] in the massless limit of NMG.Footnote 1 The aim of this paper is to show that the equation for the massless scalar, remarkably, can be solved analytically on these backgrounds, and that the quasinormal frequencies can be found in a closed manner. As usual, we require ingoing boundary condition at the horizon. We show that at infinity the natural boundary condition that makes the action principle for the scalar to be well-defined is that the field must vanish sufficiently fast. This is one of the few known, rotating black holes, that admit such integration.

This paper is organized as follows: Sect. 1 introduces the theory of new massive gravity and presents the asymptotically locally flat, rotating black hole solution. In Sect. 2 we consider a massless scalar field perturbation and solve it in an exact and analytic manner. We find the quasinormal modes in a closed form in the rotating case and show that as the angular momentum of the black hole decreases the imaginary part of the frequencies approach minus infinity. This is consistent with the fact that in the static case, the algebraic equations that determine the spectrum cannot be fulfilled. We therefore explore the behavior of the quasinormal frequencies in terms of the global charges of the background solution. Even though our interests is in the propagation of a scalar probe on the black hole background, let us mentions that our results could shed some light on the stability of the rotating black hole in NMG. Since the full non-linear field equations of NMG are of fourth order, their linearized version around a generic background will be in general of the same order. Nevertheless, there could be an affective quantity, constructed with second derivatives of the perturbation, which may have a second order dynamics, as it occurs in the Teukolsky equation, where the unknowns are linearized expressions for the components of the Weyl tensor in a null tetrad [28]. It is also worth mentioning that in some particular cases in GR it is known that the dynamics of some of the modes of the full gravitational perturbation coincide with the dynamics of a scalar probe with a given mass. This happens for example in the massless topological black hole [27]. A less striking connection between a scalar probe and a gravitational perturbation occurs with the Regge–Wheeler equation, which has the same functional form than the equation for a massless scalar probe in Schwarzschild background, but in this case there is a single numeric coefficient of difference in the effective Schroedinger potential (see [28]). Section 3 contains conclusions and further comments.

2 Massless limit of NMG and its rotating black hole

The theory of New Massive Gravity [9], has the following action

Note that the Einstein term has the wrong sign, which is necessary to obtain a ghost free theory for a massive graviton, at the linearized level around flat space. Since General Relativity does not propagate local degrees of freedom in three dimensions, we can choose the sign of the Einstein term at convenience. The massless limit is described by the purely quadratic theory which acquires a linearized conformal invariance [13], and despite the fact of having fourth order field equations, it defines a healthy theory [10]. We take the limit in the following manner \(m\rightarrow 0\) and \(\kappa \rightarrow +\infty \) with \(16\pi G:=\kappa ^{2}m^{2}\) fixed. The field equations in vacuum are therefore given by

Diffeomorphism invariance of the original action ensures the identity \(\nabla ^{\mu }K_{\mu \nu }\equiv 0\). This is the unique quadratic combination in three dimensions that leads to field equations of fourth order, whose trace reduces to a second order constraint [11]. This feature is of fundamental importance when proving the healthiness of the theory. The theory defined by the field equations (2) has the following rotating black hole solution

with

It can be checked that this spacetime has a vanishing Cotton tensor, and it is therefore a solution of Conformal Gravity in \(2+1\) dimensions (the massless limit of Topologically Massive Gravity [29,30,31]). In such context, the static solution was originally reported in [32]. The spacetime (3), is characterized by three parameters b, a and \(\mu \) which determine the global charges associated to the asymptotic Killing vectors \(\partial _{t}\) and \(\partial _{\phi }\), i.e. the mass and the angular momentum, respectively, which are given by [25]

Note that the parameter \(\mu \) does not appear in the global charges, and therefore can be interpreted as a hair of gravitational origin. Further thermodynamical properties are the temperature and the entropy of the black hole that respectively read

The remaining chemical potential, the angular velocity of the horizon, vanishes. The metric (3) can be obtained from the rotating solution of Cosmological New Massive Gravity at the point of coinciding vacua [12], in the limit \(l\rightarrow +\infty \), by a suitable rescaling of the integration constants. This solution can also be written in null coordinates, adapted to future null infinity as

where the change of coordinates that relates (3) and (7) is

Hereafter we will use the metric in the coordinate system defined in Eq. (3). The event horizon is located at \(r=r_{+}=\mu /b\), and the metric is asymptotically locally flat, i.e.

3 Massless scalar on the rotating black hole

Consider a massless scalar \(\Phi \), on the rotating black hole metric (3)

As usual, the symmetries of the background allow to consider the following mode decomposition

Hereafter we denote \(R_{\omega ,n}\left( r\right) =R\left( r\right) \). One therefore obtains an ODE for the radial dependence, which acquires a simple fashion in terms of the coordinate x, such that

that maps the domain \(r\in [r_{+},+\infty [\) to the range \(x\in [0,+\infty [\). The equation for \(R\left( x\right) \) therefore reads

with

Near the event horizon, located at \(x=0\), the solutions of Eq. (15) allow for the following asymptotic behaviors

while at infinity the scalar behaves as

where

Here \(C_{1,2}\) an \({\tilde{C}}_{1,2}\) are integration constants. Note that since the angular velocity of the horizon vanishes, the leading dependence of the scalar on the near horizon region does not depend on the rotation parameter a.

A remarkable fact is that even though (15) describes the radial dependence of a scalar on a rotating black hole, it can be solved in an analytic manner in terms of Hypergeometric functions. The solution of (15) is given by

where F stands for a hypergeometric function \(_{2}F_{1}\), and

For quasinormal modes we must require that the energy flux at the horizon must be ingoing, therefore using the fact that \(_{2}F_{1}\left( \mu ,\nu ,\sigma ,0\right) =1\) one sees that \(C_{2}\) in (22) must vanish. Consequently, one obtains

Using Kummer relations for the Hypergeometric Functions [33], leads to the following asymptotic behavior at infinity (\(x\rightarrow +\infty \)) for (26):

where \(\xi \) is a non-vanishing constant. In general \(\delta _{\pm }=\frac{1}{2}\left( 1\pm \sqrt{1-\frac{4\omega ^{2}}{b^{2}}}\right) \) will be complex numbers, related by \(\delta _{+}+\delta _{-}=1\).

The dynamics of the scalar field on the rotating black hole background comes from the action principle

whose variation reads

which on-shell reduces to a pure boundary term

Requiring the action principle to be well-defined implies that \(\delta _{\text {on-shell}}I\left[ \phi \right] =0\), which using the asymptotic expansion (27) implies

In the limit \(x\rightarrow \infty \) the first term goes to zero since \(\mathfrak {R}(2\delta _+-1)>0\), the second term is a constant and the third term is divergent since \(\mathfrak {R}(2\delta _--1)<0\). The last two terms must vanish independently, and therefore we need to impose that their common factor vanishes by imposing \(\Gamma (\alpha )\rightarrow \infty \) or \(\Gamma (\gamma -\beta )\rightarrow \infty \). These condition lead to the equations for the spectrum

where p and q take integer values \(0,1,2,3,.\ldots \). Conditions (32) lead to the determination of the spectrum of quasinormal frequencies for ingoing boundary condition at the horizon and on-shell vanishing boundary term of the variation of the action functional at infinity (30). We can introduce the reduced quantities

in terms of which the constraints (32) that determine the spectrum read,

The union of the loci in the complex \(\omega \)-plane defined by the Eqs. (34) and (35), defines the quasinormal spectrum of the rotating black hole. The integers p and q, determine the overtones. As mentioned above, note that \({\mathcal {C}}_1({\hat{J}},n)={\mathcal {C}}_2(-{\hat{J}},-n)\) with p interchanged by q. We observe that the constraint \({\mathcal {C}}_1=0\)(\({\mathcal {C}}_2=0\)) can be solved only for positive(negative) values of the black hole angular momentum \({\hat{J}}\), but due to the symmetry mentioned above, as expected, both constraints will lie on the same locus.

Consequently, in terms of the reduced angular momentum \({\hat{J}}=J/\sqrt{M}\), the reduced frequencies \({\hat{\omega }}=\omega /\sqrt{M}\) can be conveniently summarized as

where we have defined \(\nu :=\sqrt{2{\hat{J}}^{2}+\mu }\) and set Newton’s constant \(G=1/2\). \(\sigma _x\) stands for the sign of x, defined such that \(\sigma _0=1\).

Some comments on the boundary conditions are in order. For asymptotically flat black holes in four dimensions, as for example in the Kerr family, the scalar field has two possible behaviors at infinity which are plane waves that describe the out-going and the in-coming modes, and therefore the leading contribution goes as \(e^{-i\omega \left( t\pm r\right) }\) with the plus(minus) sign standing for the in-coming(out-going) mode. The background of the rotating asymptotically, locally flat, black hole of New Massive Gravity allows different behaviors at infinity, which are given in (27). Even in terms of the proper radial distance at infinity \(\rho =\frac{2}{\sqrt{b}}\sqrt{r}\), one would have \(x\sim \rho ^{2}\), and the behavior (27) would still have a power law fashion and would not be compatible with the interpretation of an out-going or in-coming plane wave. The situation at hand is actually more similar to the analysis of quasinormal modes in asymptotically AdS black holes where the leading asymptotic behaviors are \(r^{-\Delta _{\pm }}\) and \(\Delta _{\pm }\) are given in terms of the mass of the field and the dimension of the spacetime, defining the conformal weights of the operator dual to the scalar on the boundary CFT. Therefore, with the asymptotic behaviors given by Eq. (27) a natural physical condition that allows to compute the quasinormal frequencies is to require that the field at infinity decays fast enough as to lead to a well defined variational principle (30) and this is in fact the strategy we have followed.

Below we present plots of the QNM spectrum of the scalar probe in terms of the physical variables, as well as closed analytic expressions for the asymptotic behavior of the frequencies.

3.1 Static case and asymptotic frequencies

Let’s analyze first the static case. We set \(J=0\) in (34) and (35). Then from (34) one obtains two equations for the real and imaginary part of the constraint, whose real part reads

This equation does not have solution for any value of \(\omega =\omega _{r}+i\omega _{i}\) (with \(\omega _{r,i}\) finite), and therefore (34) cannot be fulfilled. A similar analysis of the real part of (35) leads to the same equation (with p changed by q). This is a peculiar feature of the static solution: there are no massless scalar field quasinormal modes for the asymptotically flat, static black hole with gravitational hair in NMG. The constraints (34) and (35) can be mapped to the Riemann sphere, where it can be seen that at the leading order when \(\omega _{i}\rightarrow -\infty \) (for constant \(\omega _{r}\)) the constraint is indeed solved since (37) reads

which vanishes when \(\omega _{i}\rightarrow -\infty \). This result is recovered from the quasinormal modes of the rotating case. We will see that as \(J\rightarrow 0\), the imaginary part of the quasinormal frequencies tend to \(-\infty \), and therefore the quasinormal modes acquire an infinity damping in this limit, and migrate to the north pole of the Riemann Sphere.Footnote 2

3.2 The quasinormal spectrum

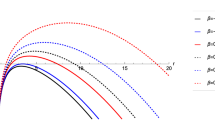

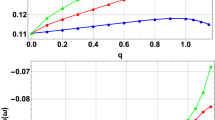

In this section we present different plots that clarify the behavior of the spectra as a function of the parameters of the problem, with descriptive captions (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Left panel: spectra for different values \(\mu \), and \(p=1\). For \(n=1\). The curves start on the imaginary axis (\({\hat{J}}\rightarrow -\infty \)), then acquire a positive real part, approach the north pole of the Riemann sphere (\({\hat{J}}\rightarrow 0^-\)), then pass through the pole and acquire a negative real part, and end again in the imaginary axis as \({\hat{J}}\rightarrow +\infty \). For \(n=-1\) the locus is exactly the same but has the opposite orientation. The right panel shows the projection to the Riemann sphere of the spectrum for \(\mu =0.1\), \(p=0\) and \(n=1\) showing that the north pole is reached as \({\hat{J}}\) goes to zero

Spectrum for different values of n. The modes with \(n=0\) lie on the imaginary axis for any J which runs along the curves. We have fixed \(\mu =0.01\) and left panel shows the fundamental mode \(p=0\) while right panel shows the modes with \(p=2\). As expected, for a given value of the reduced angular momentum \({\hat{J}}\), the modes with higher overtones have a higher damping

Quasinormal spectrum for the fundamental (\(p=0\)) and first excited mode (\(p=1\)) for different values of the gravitational hair parameter \(\mu \). As \(\mu \) increases the modes acquire a higher damping (we have set \({\hat{J}}=n=1\)). We observe that \(\mathfrak {I}({{\hat{\omega }}})<-\sqrt{2}\) and approaches the bound for small \(\mu \) and large n and \(p=0\). For modes with higher overtones the negative, upper bound on the imaginary part of the frequencies is always lower, leading to higher damping

3.3 Asymptotic frequencies

Finally let’s analyze two informative asymptotic behaviors for the spectrum. First, for large angular momentum of the field the asymptotic expansion \(n\rightarrow +\infty \) reads

It is interesting to notice that this behavior is reminiscent of that of the quasinormal modes of a scalar field with large angular momentum j on Schwarzschild black hole. In that case one has [36]

It is also interesting to put special attention to the case with arbitrarily large J, since this cannot be reached within the Kerr family. (It can be reached in Myers–Perry in \(d>5\) [37]). Quasinormal frequencies \({\hat{\omega }}\) in the limit \({\hat{J}}\rightarrow \infty \) becomes purely imaginary (damped) and depend only on the overtone integer

The fundamental mode in this regime is \( {\hat{\omega }}_{{\hat{J}}\rightarrow \infty }^{0}=-2\, i\). The function \({\hat{\omega }}_{{\hat{J}}\rightarrow \infty }(p)\) at large p approaches a straight line with slope \(2\sqrt{2}\).

4 Conclusions

In this paper we have shown that a massless scalar probe on the asymptotically locally flat, rotating black hole of pure NMG can be analytically solved leading to an exact expression for the quasinormal mode frequencies. We have imposed ingoing boundary conditions at the horizon and a decay at infinity which is fast enough leading to a well defined variational principle for the scalar probe. For a given black hole, parametrized by the mass, angular momentum and gravitational hair, the quasinormal spectrum is defined by the angular momentum of the field as well as an integer counting overtones. We showed that under these boundary conditions the imaginary part of the frequencies is always negative, not leading to any superradiance, as expected for a massless scalar. Even more, when the angular momentum of the black hole approaches zero, the imaginary part of the frequencies tends to minus infinity leading to infinitely damped modes. Remarkably, this is one of the few examples of rotating black holes in which the quasinormal frequencies for a scalar probe can be obtained in an analytic, closed form.Footnote 3

Since the rotating black hole, even in the case with cosmological constant, has vanishing Cotton tensor [12, 13], it is a conformally flat spacetime, therefore the solution for a conformal scalar could also be obtained in an analytic manner by applying a conformal transformation to the solution of the free, massless scalar of 3D Minkowski or AdS space (since the latter is also conformally flat). Once the mapping is done on the general solution, one would have to impose the boundary conditions at the horizon and infinity taking care of the potential divergences induced by the conformal mapping that leads to the black hole.

The stable propagation of scalar probes on the rotating background may lead to the existence of rotating black holes with both scalar and gravitation hair. In NMG static black holes with self-interacting scalar hair already exist, with Lifshitz and AdS asymptotics [42, 43], and it would be interesting to construct rotating black holes with these hairs.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: The data presented in the figures come from direct parametric plots of the analytic constraints that define the spectra.]

Notes

References

M. Banados, C. Teitelboim, J. Zanelli, Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 1849 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.1849. arXiv:hep-th/9204099

J.M. Maldacena, Int. J. Theor. Phys. 38, 1113 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026654312961. arXiv:hep-th/9711200

J.M. Maldacena, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 231 (1998). https://doi.org/10.4310/ATMP.1998.v2.n2.a1

E. Witten, Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 253 (1998). https://doi.org/10.4310/ATMP.1998.v2.n2.a2. arXiv:hep-th/9802150

S.S. Gubser, I.R. Klebanov, A.M. Polyakov, Phys. Lett. B 428, 105 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(98)00377-3. arXiv:hep-th/9802109

A. Strominger, JHEP 9802, 009 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/1998/02/009. arXiv:hep-th/9712251

G.T. Horowitz, V.E. Hubeny, Phys. Rev. D 62, 024027 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.62.024027. arXiv:hep-th/9909056

D. Birmingham, I. Sachs, S.N. Solodukhin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 151301 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.151301. arXiv:hep-th/0112055

E.A. Bergshoeff, O. Hohm, P.K. Townsend, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 201301 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.201301. arXiv:0901.1766 [hep-th]

S. Deser, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 101302 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.101302. arXiv:0904.4473 [hep-th]

M. Nakasone, I. Oda, Prog. Theor. Phys. 121, 1389 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.121.1389. arXiv:0902.3531 [hep-th]

J. Oliva, D. Tempo, R. Troncoso, JHEP 0907, 011 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/2009/07/011. arXiv:0905.1545 [hep-th]

E.A. Bergshoeff, O. Hohm, P.K. Townsend, Phys. Rev. D 79, 124042 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.79.124042. arXiv:0905.1259 [hep-th]

G. Giribet, J. Oliva, D. Tempo, R. Troncoso, Phys. Rev. D 80, 124046 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.80.124046. arXiv:0909.2564 [hep-th]

G. Arcioni, C. Dappiaggi, Class. Quantum Gravity 21, 5655 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/21/23/022. arXiv:hep-th/0312186

C. Dappiaggi, JHEP 0411, 011 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/2004/11/011. arXiv:hep-th/0410026

A. Bagchi, S. Detournay, R. Fareghbal, J. Simón, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110(14), 141302 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.141302. arXiv:1208.4372 [hep-th]

R. Fareghbal, S.M. Hosseini, Phys. Rev. D 91(8), 084025 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.91.084025. arXiv:1412.2569 [hep-th]

S.W. Hawking, arXiv:1509.01147 [hep-th]

L. Donnay, G. Giribet, H.A. Gonzalez, M. Pino, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116(9), 091101 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.091101. arXiv:1511.08687 [hep-th]

S.W. Hawking, M.J. Perry, A. Strominger, Phys. Rev. Lett. 116(23), 231301 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.231301. arXiv:1601.00921 [hep-th]

S.W. Hawking, M.J. Perry, A. Strominger, JHEP 1705, 161 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP05(2017)161. arXiv:1611.09175 [hep-th]

G. Alkaç, E. Kilicarslan, B. Tekin, Phys. Rev. D 93(8), 084003 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.93.084003. arXiv:1601.06696 [hep-th]

S. Haco, S.W. Hawking, M.J. Perry, A. Strominger, JHEP 1812, 098 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP12(2018)098. arXiv:1810.01847 [hep-th]

G. Barnich, C. Troessaert, D. Tempo, R. Troncoso, Phys. Rev. D 93(8), 084001 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.93.084001. arXiv:1512.05410 [hep-th]

I. Gullu, T.C. Sisman, B. Tekin, Class. Quantum Gravity 27, 162001 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/27/16/162001. arXiv:1003.3935 [hep-th]

D. Birmingham, S. Mokhtari, Phys. Rev. D 74, 084026 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.74.084026. arXiv:hep-th/0609028

S. Chandrasekhar, (Clarendon, Oxford, 1985), p. 646

S. Deser, R. Jackiw, S. Templeton, Phys. Rev. Lett. 48, 975 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.975

S. Deser, R. Jackiw, S. Templeton, Ann. Phys. 140, 372 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(82)90164-6

S. Deser, R. Jackiw, S. Templeton, Ann. Phys. 281, 409 (2000). Erratum: [Ann. Phys. 185, 406 (1988)]. https://doi.org/10.1006/aphy.2000.6013

J. Oliva, D. Tempo, R. Troncoso, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 24, 1588 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217751X09045054. arXiv:0905.1510 [hep-th]

M. Abramowitz, I.A. Stegun (eds.), Handbook of Mathematical Functions: With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (Dover Publications, Mineola, 1965)

Y. Kwon, S. Nam, J.D. Park, S.H. Yi, Class. Quantum Gravity 28, 145006 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/28/14/145006. arXiv:1102.0138 [hep-th]

P.A. González, Y. Vásquez, Eur. Phys. J. C 74(7), 2969 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-014-2969-1. arXiv:1404.5371 [gr-qc]

V. Ferrari, B. Mashhoon, Phys. Rev. D 30, 295 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.30.295

R.C. Myers, M.J. Perry, Ann. Phys. 172, 304 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(86)90186-7

I. Ichinose, Y. Satoh, Nucl. Phys. B 447, 340 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(95)00197-Z. arXiv:hep-th/9412144

M. Cvetic, G.W. Gibbons, Z.H. Saleem, Phys. Rev. D 90(12), 124046 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.90.124046. arXiv:1401.0544 [hep-th]

M. Cvetic, G.W. Gibbons, Phys. Rev. D 89(6), 064057 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.89.064057. arXiv:1312.2250 [gr-qc]

E. Berti, V. Cardoso, A.O. Starinets, Class. Quantum Gravity 26, 163001 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/26/16/163001. arXiv:0905.2975 [gr-qc]

F. Correa, M. Hassaïne, J. Oliva, Phys. Rev. D 89(12), 124005 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.89.124005. arXiv:1403.6479 [hep-th]

E. Ayón-Beato, M. Bravo-Gaete, F. Correa, M. Hassaïne, M. M. Juárez-Aubry and J. Oliva, Phys. Rev. D 91(6), 064006 (2015). Addendum: [Phys. Rev. D 96(4), 049903 (2017)]. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.91.064006. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.96.049903 arXiv:1501.01244 [gr-qc]

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Gaston Giribet and Nicolas Grandi for enlightening comments. This work was partially supported by FONDECYT Grants 1170279 and 1181047. O.F. is supported by the Project DINREG 19/2018 of the Dirección de Investigación of the Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Anabalón, A., Fierro, O., Figueroa, J. et al. Scalar field quasinormal modes on asymptotically locally flat rotating black holes in three dimensions. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 281 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6748-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6748-x