Abstract

The \(\rho \rho \) interaction and the corresponding dynamically generated bound states are revisited. We demonstrate that an improved unitarization method is necessary to study the pole structures of amplitudes outside the near-threshold region. In this work, we extend the study of the covariant \(\rho \rho \) scattering in a unitarized chiral theory to the S-wave interactions for the whole vector-meson nonet. We demonstrate that there are unphysical left-hand cuts in the on-shell factorization approach of the Bethe–Salpeter equation. This is in conflict with the correct analytic behavior and makes the so-obtained poles, corresponding to possible bound states or resonances, unreliable. To avoid this difficulty, we employ the first iterated solution of the N / D method and investigate the possible dynamically generated resonances from vector-vector interactions. A comparison with the results from the nonrelativistic calculation is provided as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

At very low energies, the strong interactions among the lowest-lying pseudoscalars, i.e. \(\pi \), K and \(\eta \), are successfully described by chiral perturbation theory (ChPT) [1,2,3]. To extend such a theory to higher energies, heavier meson resonances must be incorporated, with the light vector-meson nonet, i.e. \(\rho \), \(K^*\), \(\omega \) and \(\phi \), being the most important one. To that end, various approaches have been proposed, among which the most convenient scheme was suggested in Ref. [4] and further developed by Callan, Coleman, Wess and Zumino in their classical works [5, 6], known as the CCWZ formalism. In this scheme, low-energy theorems are easily built in and the vector mesons transform homogeneously under a nonlinear realization of the chiral symmetry. While the leading order effective Lagrangian for vectors are fully determined by the chiral symmetry, the low-energy constants (LECs) of higher orders are not constrained and have to be fixed by experimental measurements and lattice data in principle. The framework for investigating the dynamics of resonances in a chiral theory has been laid out in Refs. [7, 8] along these lines. Recently, a chiral expansion of the masses and decay constants of those low-lying mesons was proposed up to one-loop order in Ref. [9], see also Refs. [10,11,12].

Alternatively, the phenomenological success of vector meson dominance and especially the universality of the \(\rho \)-couplings [13], i.e. \(g_{\rho \pi \pi }\approx g_{\rho NN}\), have motivated the massive Yang-Mills method [14] and the hidden local symmetry approach [15, 16]. In these treatments, low-energy theorems impose important constraints on the \(\rho \)-couplings. Based on a linear realization of the chiral symmetry, both the vectors \(\rho \) and its chiral partners \(a_1\) must be treated on the same footing in the massive Yang-Mills method. The chiral low-energy theorems are not immediately obvious at the Lagrangian level and are obtained after some delicate cancellations. A further complication comes from the presence of the \(\pi a_1\) mixing, although it can be removed by an appropriate shift in the definition of the axial vector fields [14]. Based on that a nonlinear sigma model on the coset space G / H is gauge equivalent to a linear model with \(G_\text {global}\times H_\text {local}\), the \(\rho \) mesons were suggested as the dynamical gauge bosons of the hidden local symmetry \(H_\text {local}\) [15, 16], and their masses are generated via the Higgs mechanism. By this treatment the effective chiral Lagrangian is fixed up to one parameter, and the celebrated Kawarabayashi–Suzuki–Riazuddin–Fayyazuddin (KSRF) relations [17, 18], i.e. \(g_\rho = 2 g_{\rho \pi \pi } F_\pi ^2\) and \(M_\rho ^2 = 2 g_{\rho \pi \pi }^2 F_\pi ^2\), follow naturally by an appropriate choice of the parameter. Moreover, the inclusion of the electromagnetic interactions precisely yields the vector meson dominance of photon couplings [15, 16]. These approaches are in principle equivalent, and each corresponds to a different choice of the vector field, see, e.g., Refs. [19, 20]. The different choices of fields merely influence the off-shell behavior of the scattering amplitudes, and lead to the same physics. Thus, the choice of fields depends on the convenience of the corresponding Lagrangian for the specific calculations.

It is now commonly accepted that some hadronic resonances are dynamically generated by strong hadron-hadron interactions. To describe these states, different unitarization procedures were proposed. A convenient and commonly used unitarization method is the on-shell factorization approximation of the Bethe–Salpeter equation (BSE). While the unitarity cut (physical/right-hand cut) is treated nonperturbatively, the left-hand cut (dynamic sigularities [21]) are incorporated in a perturbative way [22, 23]. The coupled-channel version of the unitarization procedure was used to study the S-wave kaon-nucleon interactions for strangeness \(S=-1\) channel in a modern framework in Ref. [23] (for earlier works using different regulators, see [24, 25]) and provided a good reproduction of the event distributions in the region of the \(\Lambda (1405)\), which was predicted as a \({\bar{K}}N\) hadronic molecule by Dalitz and Tuan long ago [26]. More interestingly, the \(\Lambda (1405)\) is replaced by two nearby poles, leading to the so-called two-pole structure of the \(\Lambda (1405)\) [23, 27] (for brief reviews, see Refs. [28, 29]), due to the \(\pi \Sigma \) and \({\bar{K}} N\) coupled channels. The two-pole structure was confirmed by experiments later [30]. Recently, a similar two-pole nature of the \(D_0^*\) was reported in Refs. [31, 32], which is based on the unitarized chiral effective theory constrained by lattice calculations [33] and backed by the high quality experimental data collected at the LHCb experiment [34]. In addition, the unitarized chiral method was employed to reveal the nature of the \(f_0(980)\) as a dynamically generated resonance in the isoscalar \(\pi \pi \)–\(K\bar{K}\) system [22].

The first attempt to investigate the dynamically generated resonances (including bound states) by S-wave \(\rho \rho \) interactions was given in Ref. [35] with the potentials derived in the framework of the hidden local symmetry approach. In that work, the nonrelativistic limit, i.e. \(|{{\mathbf {p}}}|^2/M_\rho ^2 \rightarrow 0\) with \({{\mathbf {p}}}\) the three-momentum of the \(\rho \), was taken. It is found that the \(\rho \rho \) interactions in the channel \(I=0\), \(J=0\) and \(I=0\), \(J=2\) channels, with I the isospin and J the total spin, are attractive enough to produce bound states, which are assigned to the \(f_0(1370)\) and \(f_2(1270)\) resonances, respectively. Furthermore, the fact that the tensor meson is lighter than the scalar one is attributed to the stronger attraction in the corresponding channel. However, as pointed out in Ref. [36], the \(f_2(1270)\) fits very well within a nearly ideally-mixed P-wave \(q\bar{q}\) nonet [37,38,39]. The \(q\bar{q}\) picture of the \(f_2(1270)\) is also supported by the experimental data on \(\gamma \gamma \rightarrow \pi \pi \) [40, 41]. One notices that the \(\rho \rho \) bound state assignment of the \(f_2(1270)\) in Ref. [35] is based on the nonrelativistic limit although the binding momentum in this case reaches about 445 MeV. The interaction was over-extrapolated to the region where the relativistic effect has to be taken into account, see e.g. Ref. [36]. Moreover, the t- and u-channel \(\rho \)-exchange diagrams shrink to contact terms for the four-\(\rho \) interactions in Ref. [35] and thus the corresponding left-hand cuts are neglected. A scrutinization of the extreme nonrelativistic approximation can be found in Ref. [36], where a covariant formalism using relativistic propagators is employed and possible generated resonances are revisited. Furthermore, the unitarization procedure is improved using the first iterated solution of the N / D dispersion relation. It turns out that while a bound state pole corresponding to the \(f_0(1370)\) is found, there is no pole which can be associated with the \(f_2(1270)\).

In a following work, i.e. Ref. [42], the authors examine the the relativistically covariant \(\rho \rho \) interaction and argue that the disappearance of the tensor bound state in Ref. [36] is due to the on-shell factorization of the potential done in the region where an “unphysical” discontinuity (imaginary part) is developed by the left-hand cut. The authors of Ref. [42] argue that the one-loop integrals for the t-channel \(\rho \)-exchange triangle and box diagrams do not have an imaginary part and thus the left-hand cut \(s\le 3 M_\rho ^2\) would be unphysical. The singularities of the triangle and box diagrams by putting at least two intermediate \(\rho \) mesons on shell are the triangle and box Landau singularities [43], and they indeed do not appear in the physical Riemann sheet for the processes in the energy region of interest according to the Coleman–Norton theorem [44].Footnote 1 It is only due to the use of on-shell factorization so that such a left-hand cut appears wrongly on the physical Riemann sheet, and is thus called “unphysical”. It is worthwhile to emphasize that this issue and the related on-shell factorization problem have been overcome in Ref. [36] by using the first iterated solution of the N / D dispersion relation, and still no tensor pole was found as mentioned above.

At the first sight, it seems to be surprising that a bound state appears in the sector \((I,J)=(0,0)\), while there is no \((I,J)=(0,2)\) bound state though the interaction is also attractive with a strength at threshold twice of that in the scalar sector. As is well-known, in the energy range not very close to the threshold, higher orders in the effective range expansion, and thus the energy dependence in the potential, become important. That is to say, in addition to the attractive strength at threshold, which is proportional to the scattering length a, the effective range \(r_0\) is also crucial to form a deeply-bound state. The effective range is determined by

around the threshold with p the three-momentum and \(s=E^2\) the total energy squared in the center-of-mass frame. It is easy to see that \(r_0\) is proportional to the derivative of \(\sqrt{s}T^{-1}(s)\) with respect to the energy at the threshold. As a result, with the increasing of the slope of the potential as a function of energy, the effective range decreases. As can be seen from Fig. 4 in Ref. [36], the effective range for \((I,J)=(0,0)\) is much larger than that in the tensor sector. A naive calculation with the tree-level potential shows that the tensor sector even has a negative effective range.Footnote 2 From the D function plotted in Fig. 11 in Ref. [36], where the problems of the on-shell factorization have been cured, it can be seen that the disappearance of the tensor bound state stems from the energy-dependence of the potential instead of the left-hand cut.

The extension of the vector-vector interaction to SU(3) is given in Ref. [45]. Up to 11 dynamically generated states were reported. While six of them were assigned to the \(f_0(1370)\), \(f_0(1710)\), \(f_2(1270)\), \(f_2^\prime (1525)\), \(a_2(1320)\) and \(K_2^*(1430)\) resonances, more states with quantum numbers of the \(h_1\), \(a_0\), \(b_1\), \(K_0^*\) and \(K_1\) were predicted. However, since that work employed the same nonrelativistic formalism as that in Ref. [35], a recalculation keeping the t- and u-channel vector-meson propagators using the method of Ref. [36] is needed, which is the scope of this paper.

This work is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the effective Lagrangian in the hidden local symmetry approach is briefly introduced and the scattering amplitudes are calculated, followed by the partial wave projection. In Sect. 3, the on-shell factorization of the BSE is applied to the single-channels, and poles are searched for in the energy range outside of the left-hand cuts. The improved unitarization formula using the first iterated solution of the N / D dispersion relation [36] is employed in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 comprises a summary and outlook.

2 Formalism

2.1 Effective Lagrangian in hidden local symmetry approach

Various approaches including the light vector mesons in an effective theory respecting the chiral symmetry are proven to be equivalent, e.g. see Refs. [19, 20]. In this work, we employ the hidden local symmetry formalism in which the vectors are treated as gauge bosons of a hidden local symmetry transforming inhomogeneously. In this approach, the phenomenologically successful KSRF relations, vector-meson dominance and the universality of \(\rho \)-couplings, as well as the Weinberg–Tomozawa theorem for \(\pi \)-\(\rho \) scattering, can be obtained.

In the hidden local symmetry approach, the global chiral symmetry is encoded into a SU(3) matrix U(x). The local symmetry is introduced by factorizing U(x) into two SU(3) matrices [15, 19, 20]

This factorization is arbitrary at each space-time point, which is equivalent to a local SU(3) symmetry. Vector mesons \(V_\mu \) are introduced as the gauge bosons of this local symmetry. The leading order Lagrangian has the form [15, 19, 20]

where \(F_\pi \) is the pion decay constant, \(F_\pi = 93\) MeVFootnote 3, \(\langle \dots \rangle \) represents a trace over SU(3) flavor space, and a is a real parameter. Further,

and

is the corresponding gauge-covariant field strengths with g the gauge coupling constant.

By choosing the unitary gauge, i.e.

one obtains the Lagrangian

where

The Goldstone bosons \(\Phi \) are nonlinearly encoded in \(u(x) = \exp \big ( i\Phi / (\sqrt{2}F_\pi ) \big )\) with

and the vector-meson matrix \(V_\mu \) has the form

The first term in Eq. (6) is identical to the familiar leading order chiral Lagrangian for pseudoscalar mesons [3], the second term contains the \(V\Phi \Phi \) interaction and the vector mass term, and the kinetic term (as well as the self-interaction) of \(V_\mu \) is given in the last term. Expanding the Lagrangian (6) up to two pseudoscalars, one finds

In this work, we choose \(a=2\), which leads to the celebrated KSRF relations and universality of the \(\rho \) couplings.

2.2 Scattering amplitudes

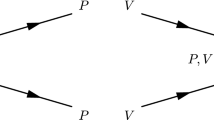

With the Lagrangian given in Eq. (10), we are in the position to calculate the vector-vector scattering amplitudes. At tree level, the Feynman diagrams needed are displayed in Fig. 1, where the t- and u-channel vector-exchange diagrams are not shown explicitly. The amplitude for the process \(V_1(p_1)V_2(p_2)\rightarrow V_3(p_3)V_4(p_4)\) can be written as

where \(A_c\), \(A_s\), \(A_t\) and \(A_u\) correspond to the four-vector contact diagrams, i.e. Fig. 1a, s-, t- and u-channel vector-exchange diagrams, respectively. Here, the Mandelstam variables are defined as \(s=(p_1+p_2)^2\), \(t=(p_1-p_3)^2\) and \(u=(p_1-p_4)^2\), which satisfy the constraint \(s+t+u=\sum _i p_i^2 =\sum _i M_{V_i}^2\), where the last equality holds when the initial and final vector mesons are on shell.

The contributions from the contact amplitudes from \({\mathcal {L}}_{VVVV}\) do not depend on the vector momenta explicitly, and are given by

where \(\epsilon _i^{(*)}\) is the polarization vector of the ith external vector meson. The \(C_i\)’s are coupling constants given in Table 1. The polarization vector can be characterized by the corresponding three-momentum \({{\mathbf {p}}}_i\) and the third component of the spin in its rest frame, and the explicit expression for the polarization vectors can be found in Appendix A of Ref. [36]. The two structures in Eq. (12) are symmetric by exchanging \(\epsilon _2\leftrightarrow \epsilon _4^*\) due to the two operators in \({\mathcal {L}}_{VVVV}\), c.f. Eq. (4).

Considering the vector-exchange amplitudes, for the s-channel diagram exchanging a vector V with mass \(M_V\), it takes the form

with \(M_i\) the mass of the \(i^\text {th}\) external vector meson. The t- and u-channel amplitudes \(A_t^V\) and \(A_u^V\) can be obtained from \(A_s^V\) by performing the exchange \(p_2 \leftrightarrow -p_3\), \(\epsilon _2\leftrightarrow \epsilon _3^*\) and \(p_2 \leftrightarrow -p_4\), \(\epsilon _2\leftrightarrow \epsilon _4^*\), respectively. \(C_s^V\) is a coupling constant given in Table 1.

It is more convenient to study the scattering amplitudes in the isospin basis instead of the particle basis. The scattering processes can be classified by the strangeness S and isospin I of the system. There are 7 independent combinations in total. The corresponding quantum numbers (S, I) of the scattering systems are (0, 0), (0, 1), (0, 2), (1, 1 / 2), (1, 3 / 2), (2, 0) and (2, 1), among which (0, 2), (1, 3 / 2), (2, 0) and (2, 1) are single-channel processes. For \((S,I)=(0,0)\), there are five channels: \(\rho \rho \), \(K^*\bar{K}^*\), \(\omega \omega \), \(\omega \phi \) and \(\phi \phi \). For \((S,I)=(0,1)\), there are four channels: \(\rho \rho \), \(K\bar{K}^*\), \(\rho \omega \) and \(\rho \phi \), and for \((S,I)=(1,1/2)\) there are three channels: \(\rho K^*\), \(K^*\omega \) and \(K^*\phi \). The phase convention we use to relate the particle basis to the isospin basis is such that

while all the other states have a positive sign.

In the (S, I) basis, the tree level scattering amplitudes are given by

where the coefficients are collected in Table 1.

2.3 Partial wave amplitudes

For a relativistic system, the orbital angular momentum L and the total spin \(\Sigma \) are not good quantum numbers. Instead, the total angular momentum J is conserved. Since we are interested in systems with definite strangeness and isospin (S, I), hereafter we will neglect the (S, I) index for brevity. A complete basis for the angular momentum coupling of a two-vector system could be chosen as the total angular momentum J, the corresponding third component M, the orbital angular momentum L and the total spin \(\Sigma \), among which only J and M are good quantum numbers. A state \(|JM,L \Sigma \rangle \) can be expressed in terms of the states \(|{{\mathbf {p}}},\sigma _1\sigma _2\rangle \) which is the direct product of the one-particle states \(|{{\mathbf {p}}},\sigma _1\rangle \) and \(|-{{\mathbf {p}}},\sigma _2\rangle \) with \(\sigma _i\) the third component of spin for particle i and \({\mathbf {p}}\) the momentum in the center-of-mass frame [36],

with \(s_i=1\) the spin of the ith vector meson, and \((m_1m_2 M|l_1l_2 L)\) denotes the pertinent Clebsch–Gordan coefficient. If the two vector mesons are identical particles, an extra symmetrization factor \(1/\sqrt{2}\) is required in Eq. (16).

For a complete consideration of coupled channels, in general, all transitions between states with the same J need to be taken into account with the transition matrix elements

with \({\hat{T}}\) the scattering operator. Note that the partial wave amplitudes in Eq. (17) are independent of the third component M due to the rotational symmetry. Thus, the expression of Eq. (17) can be written as [36]

with the z-axis defined as the direction of \(\mathbf{p}_1\), i.e., \(\mathbf{p_1}=|\mathbf{p}|\hat{\mathbf{z}}\), \({\mathbf{p}_2}= -|\mathbf{p}|\hat{\mathbf{z}}\), \(\mathbf{p_3}= {\mathbf{p}^\prime }\), \(\mathbf{p_4}=-{\mathbf{p}^\prime }\), \(\Sigma _3=\sigma _1+\sigma _2\) and \(\Sigma _3^\prime = \sigma _1^\prime +\sigma _2^\prime \). In this work, we are only interested in the S-wave scattering amplitudes, thus we set \(L=L^\prime =0\). In principle, the transition amplitudes with different orbital angular momenta should be taken into account as long as the total angular momentum J is conserved. However, it would introduce extreme complications due to the large number of different possible orbital angular momenta although we are only interested in \(J=0\), 1, and 2. Both S and D waves are considered for SU(2) case in Ref. [36], where the inclusion of S–D-wave coupled channels leads to the presence of an artificial pole with anomalous properties. It has a negative residue, which is at odds with the probabilistic interpretation of a bound state. The presence of this extra pole is attributed to the unitarization which treats the left-hand cut perturbatively. Apart from that, including S–D-wave coupling produces a physical pole with properties close to that in the purely S-wave case. For simplicity, we only focus on the channels with \(L=0\) and neglect contributions from higher L in what follows.

The partial wave projection Eq. (18) for a t-channel exchange amplitude would develop a left-hand cut by

with \(\lambda (a,b,c)=a^2+b^2+c^2-2ab-2bc-2ac\) the Källén function. A projection for a u-channel can be obtained from Eq. (19) by the interchanging \(p_3\leftrightarrow p_4\). One notices that the location of the branch points depend on the involved masses, thus on the channel, and \(M_i^2\) in the above equation comes from putting the external particles on their mass shells, \(p_i^2=M_i^2\). In the coupled-channel case, the intermediate particles are not on shell. If they are put on shell, then the corresponding left-hand cuts would be transported into all coupled channels via Eq. (20), and become unphysical for the T-matrix elements for which they are not the external particles. In general, the presence of such unphysical left-hand cuts is not disturbing as long as they are located far below the lowest threshold.

3 On-shell factorization of the Bethe–Salpeter equation

The on-shell unitarization approach has been applied with great phenomenological success in previous works, see e.g. [22, 23, 27, 28, 31, 33, 46,47,48,49] (and references therein), despite of the presence of the unphysical left-hand cuts due to coupled channels. In these cases, the unphysical left-hand cuts are far away from the energy regions of interest, and thus do not cause serious problems. Nevertheless, it is known that the unphysical left-hand cuts can lead to bad analytic behavior of the coupled-channel amplitudes, see, e.g., Ref. [50]. In this section, we focus on the unitarization using the on-shell factorization, and expose the problems of this method explicitly. The basic equation for the unitarized amplitude T is given in matrix form by

where \(V^J\) denotes the partial-wave projected amplitudes, and G(s) is a diagonal matrix \(G(s)=\text {diag}\{g_i(s)\}\) with i the channel index. The fundamental loop integral \(g_i(s)\) reads

with \(P^2=s\) and \(M_{1,2}\) the masses of the particles in that channel. The T-matrix has poles at the zeros of the denominator,

or its determinant, i.e.,

for the single-channel or coupled-channel cases, respectively.

The above loop integral is logarithmically divergent and can be calculated with a once-subtracted dispersion relation. In this way, its explicit expression is [23, 51]

with

and \(a(\mu )\) is a renormalization scale (\(\mu \)) dependent subtraction constant.

Alternatively, the loop integral can be calculated with a sharp momentum-cutoff (\(q_\text {max}\)) regularization. The explicit expression of the cutoff-regularized loop integral, denoted as \(g_i^c(s)\), reads [52, 53]

with \(\Delta = M_2^2-M_1^2\). Without any prior knowledge of the subtraction constant \(a(\mu )\) (although its natural size is known [23]), the cutoff regularization enables us to evaluate the loop function \(g^c_i(s)\) with a natural value for the cutoff \(q_\text {max}\sim M_V\). In this work, to investigate the stability of the generated poles to the cutoff, we employ the values \(q_\text {max}=0.775\) GeV, 0.875 GeV and 1.0 GeV successively as in previous works [35, 36, 45].

As already mentioned in the Introduction, the left-hand cuts of the coupled-channel T-matrix in Eq. (20) using the on-shell factorization are unphysical. The locations of the left-hand branch points can be easily calculated by making use of Eqs. (19) and (15). For the case of \((S,I)=(0,0)\), while the lowest s-channel threshold is located at \(2M_\rho = 1.550\) GeV and the corresponding right-hand cut runs from \(2M_\rho \) to \(+\infty \), the left-hand cuts start from 1.606 GeV and 1.602 GeV due to the t-channel \(\rho \)- and \(\omega \)-exchange diagrams, respectively, for the intermediate process \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow K^*\bar{K}^*\). The two branch points can be clearly seen in the left panel of Fig. 2, where we plot the potential for the \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow K^*\bar{K}^*\) employing \(g={M_V}/{(2F_\pi )}=4.596\) evaluated using the average mass of vectors and \(F_\pi =93\) MeV. In addition, there are left-hand branch points at 1.558 GeV and 1.673 GeV due to the \(K^*\)-exchange for the processes \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow \omega \phi \) and \(\phi \phi \), respectively, which are above the \(\rho \rho \) threshold as well. The overlapping of the left-hand and the right-hand cuts causes a violation of unitarity using the on-shell factorized coupled-channel T-matrix in Eq. (20), and thus the reliability of the associated poles becomes problematic. A naive use of Eq. (20) to the coupled-channel case leads to a branch cut along the whole real axis. The pole found in the single-channel case below the \(\rho \rho \) threshold [36] is not reproduced in the coupled-channel case, see in Fig. 3, where the determinant Det defined in Eq. (23) for the single \(\rho \rho \) channel and the coupled-channel cases are plotted with the cutoff \(q_\text {max}=0.875\) GeV. It confirms the invalidation of Eq. (20) for the coupled-channel case with overlapping left-hand and right-hand cuts.

S-wave potentials for \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow K^*\bar{K}^*\) with \((S,I,J)=(0,0,0)\) and \(K^*\phi \rightarrow K^*\phi \) with \((S,I,J)=(1,1/2,0)\) for our calculation (real part: solid curve, imaginary part: dashed curve). The corresponding threshold and the lowest coupled-channel threshold are represented by the black and red dotted lines, respectively

The \(D_U\) function and the determinant defined in Eq. (23) of the \((S,I,J)=(0,0,0)\) unitarized amplitudes in Eq. (23) for the single channel (\(\rho \rho \)) and the coupled-channel cases evaluated with \(q_\text {max}=0.875\) GeV (real part: solid curve, imaginary part: dashed curve). Note that the imaginary part and real part of the determinant for the coupled-channel case do not vanish at the same point along the real axis below the threshold, and thus no bound state is produced

The overlapping of the left-hand and the right-hand cuts is present for all the coupled-channel cases of VV scattering, i.e. for \((S,I)=(0,0)\), (0, 1) and (1, 1 / 2), see, e.g., Fig. 2. For \((S,I)=(0,1)\), the left-hand cuts start from 1.606 GeV and 1.554 GeV for \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow K^*\bar{K}^*\) (from the t-channel \(\rho \)-exchange) and \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow \rho \phi \) (from the u-channel \(K^*\)-exchange), respectively, which are located above the lowest threshold \(2M_\rho \). The lowest threshold for the channel \((S,I)=(1,1/2)\) is 1.667 GeV, while the left-hand branch point of \(K^*\phi \rightarrow K^*\phi \) from the u-channel \(K^*\)-exchange is located at 1.689 GeV. It is worth mentioning, however, that not all left-hand cuts are present for all partial-wave projected amplitudes.

For certain values of J, the partial wave amplitude vanishes. In particular, for \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\), the only nonvanishing potential is for \( K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow K^*\bar{K}^*\), such that it reduces to a single-channel elastic scattering problem with the normal two-body threshold at 1.783 GeV, above the corresponding left-hand cuts. In fact, it is easy to show that for all elastic (single-channel) scattering processes, for s in the physical region \(s\ge (M_1+M_2)^2\), we always have \(t\le 0\) and \(u\le (M_1-M_2)^2\). For the vector-vector scattering in question, \(|M_1-M_2|\) is always smaller than any vector-meson mass, and neither the t-channel nor the u-channel exchanged vector meson can go on shell in the scattering physical region. Therefore, the left-hand cut cannot overlap with the right-hand cut, and the formula in Eq. (20) may still be employed in this case.

The right-hand cuts divide the whole energy plane into Riemann sheets. Since the right-hand cuts are included in the loop functions \(g_i(s)\), we can focus on the Riemann sheets of \(g_i(s)\). Each loop function \(g_i(s)\) has two Riemann sheets: the first (physical) and the second (unphysical) sheets, denoted as \(g_i^\text {I}(s)\) and \(g_i^\text {II}(s)\), respectively. In the first sheet, the imaginary part of the center-of-mass momentum in the corresponding channel is positive, and it is negative in the second sheet. The expressions of the loop function in the physical sheet are given in Eqs. (24) and (26), while the expressions in the second sheet can be obtained by an analytic continuation via [22]

with \(\rho _i(s)=\sigma _i(s)/(16\pi s)\) the two-body phase space factor. In this work, we are only interested in the pole structures of the unitarized amplitudes. The poles located below the threshold on the real axis in the physical Riemann sheet correspond to possible bound states, and those on the unphysical Riemann sheets correspond to possible resonances (or virtual states if the poles are on the real axis).

In this section, we focus on the single-channel cases. According to Bose symmetry, the allowed single-channel S-wave vector-meson pairs include \(\rho \rho \) with \((S,I,J)=(0,2,0)\) and (0, 2, 2), \(\rho K^*\) with (1, 3 / 2, J) with \(J=0,1\) and 2, \(K^*K^*\) with (2, 0, 1), (2, 1, 0) and (2, 1, 2), \(K^*\bar{K}^*\) with (0, 0, 1).Footnote 4 For the (2, 0, 1) \(K^*K^*\) system, a pole located at 1.613 GeV (calculated with the cutoff value \(q_\text {max}=0.875\) GeV), lower than the \(K^*K^*\) threshold 1.783 GeV, is found on the physical Riemann sheet, see the left panel of Fig. 4. It might be naively expected to be associated with a bound state of \(K^*K^*\). However, in Fig. 4, it is easy to see that the zero, denoted by the red cross, of the determinant which corresponds to a pole of the amplitude is caused by the sharp dip due to the presence of the unphysical left-hand cut, starting from 1.606 GeV, which is very close to the pole position. In this respect, this pole is just an artifact of the on-shell factorization in the unitarization formula (20), and should be absent when the on-shell factorization is removed. Furthermore, a pole at 1.724 GeV is found on the second Riemann sheet. However, from the Fig. 4, it is hard to conclude whether it is a dynamically generated state or may also be just a remnant of the unphysical left-hand cut. This issue will be revisited by making use of an improved unitarization method in the next section.

The \(D_U\) functions for the \(K^*\bar{K}^*\rightarrow K^*\bar{K}^*\) with \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\) on the real axis on the physical Riemann sheet with the cutoff \(q_\text {max}=0.775\) GeV and 1.0 GeV, respectively. The artificial pole is denoted as red cross and the pole associated with a bound state is denoted as a circle

A similar situation can be found in the \(K^*{\bar{K}}^*\) system with \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\) as well, see Fig. 5, with the left and right panels plotted with \(q_\text {max}=0.775\) and 1.0 GeV, respectively. Besides a pole near the unphysical left-hand cut and thus artificial, an additional pole close to the threshold appears in the right panel when \(q_\text {max}=1.0\) GeV. Because it is close to the threshold, its position and even its presence is sensitive to the cutoff value. As the cutoff increases, the pole position moves deeper below the threshold, while if we decrease the cutoff the pole moves towards the threshold, and at \(q_\text {max}=0.808\) GeV the pole disappears from the first Riemann sheet and shows up on the second sheet as a virtual state (on the real axis below the threshold). The parameter-sensitivity of this pole is shown in Fig. 6 and Table 2. With different choices of the cutoff, the pole appears either as a bound state or a virtual state near the threshold. The dependence of the pole on the coupling constant g is motivated by its sensitivity to the cutoff, and the values of 4.596 and 4.168 come from using the SU(3)-averaged vector-meson mass and the \(\rho \)-meson mass as \(M_V\) in \(g=M_V/(2F_\pi )\). For \(g=4.168\), the pole will become a bound state for \(q_\text {max}\ge 1.033\) GeV.

Apart from the poles located close to the unphysical left-hand cuts and thus are ruled out, the results for the single-channel cases in this work are consistent with those in Ref. [45] where a pole at \(1.802-0.078i\) GeV is reported corresponding to the pole in Table 2.Footnote 5 This is expected since this pole is very close to the corresponding threshold so that the extreme nonrelativistic approximation in Ref. [45] should work nicely. No pole is found in the other single-channel cases, consistent with the nonrelativistic results in Ref. [45].

4 First iterated solution of the N / D method

In general, the overlapping of the unphysical left-hand cut and the right-hand cut breaks unitarity and real analyticity, and thus invalidates the use of the formula in Eq. (20). One way to avoid this problem is to employ the N / D dispersion relations [36, 51, 54, 55]. According to the N / D method, a partial wave amplitude T(s) can be expressed as a quotient of two functions

where the denominator D(s) has only the unitary (right-hand) cuts and all the left-hand cuts are encoded in the numerator N(s). Poles of T(s) correspond to the zeros of the D(s) function, which is free of any left-hand cut. For the S wave, one has

where the so-called Castiliejo–Dalitz–Dyson (CDD) poles [56] are not included, and n is the number of subtractions needed to ensure the convergence such that

Eq. (29) constitutes a system of integral equations in which an input given by \(\text {Im}T(s)\) along the left-hand cut is needed.

Instead of giving a complete treatment of the N / D method, see e.g. in Refs. [57, 58], in this section we approximate the N(s) function by the tree-level amplitudes V(s). This leads to the first iterated solution as proposed in Ref. [36]. Then we have

with the \(\gamma \) parameters the subtraction constants and the subscripts i and j the channel indices. One notices that the potential matrix V(s) is inside the dispersion integral in D(s). By construction, the D(s) matrix elements in Eq. (31) are free of left-hand cuts and thus unitarity is ensured by using Eqs. (28) and (31). As we have shown in the paragraph before Eq. (27) in Sect. 3, for each individual VV scattering process, the left-hand branch points for \(V_{ij}\) from the t- and u-channel vector-exchange diagrams are below the s-channel thresholds for both i and j channels. As a consequence, the unknown subtraction constants in the D(s) functions may be fixed by matching to the denominator of Eq. (20) around the thresholds, that is [36]

where contributions of \({\mathcal {O}}\big ((s-s_\text {thr})^3\big )\) are neglected. The subtraction constants depend on the cutoff \(q_\text {max}\) via the matching conditions (32). In this way, one has

The so-obtained N and D functions have the correct analytical properties with appropriate cuts.

4.1 Single-channel cases

Real parts of the D(s) functions for the (0, 0, 1) and (2, 0, 1) cases based on the N / D method and the on-shell factorization for the BSE. The pole due to the left-hand cut is absent for (2, 0, 1), and is moved to very deep below the threshold (around 1.49 GeV) where the matching (32) is in question

In this subsection, we consider poles of the scattering amplitudes for the single-channel cases. In order to consider the possible poles on the unphysical Riemann sheet, the following continuation of the scattering amplitude is employed:

with \(T^\text {I}(s)=N(s)/D(s)\) the amplitude in the physical Riemann sheet as given in Eq. (28). Since the D(s) function, i.e. Eq. (32), is free of unphysical cuts, it is expected that the poles due to the presence of unphysical left-hand cuts found using the on-shell factorization should be absent in the N / D method. This is indeed the case for the pole on the first Riemann sheet in \(K^*K^*\) scattering, whose quantum numbers are \((S,I,J)=(2,0,1)\), as can be seen by comparing the left panel of Fig. 4 and the left panel of Fig. 7. For the \(K^*{\bar{K}}^*\) scattering with \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\), the pole on the first Riemann sheet is found much deeper than that in the BSE, see the right panel of Fig. 7. However, the pole is located far away from the \(K^*{\bar{K}}^*\) threshold such that interactions among the vector mesons other than those considered here should become relevant, and thus such a pole is not reliable. This is reflected by the dramatic dependence of the pole position on the coupling and the cutoff values: it is located between 1.42 GeV and 1.64 GeV by varying the cutoff \(q_\text {max}\) from 0.775 GeV to 1.0 GeV and the coupling g from 4.168 to 4.596. In contrast, the pole on the second Riemann sheet for the \(K^*K^*\) with \((S,I,J)=(2,0,1)\), being much closer to the \(K^*K^*\) threshold, changes only a little with the variation of the coupling constant and the cutoff, and it is a virtual state pole on the real axis. Finally, the near-threshold pole for the \(K^*{\bar{K}}^*\) with \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\) corresponding to either a bound state or a virtual state, depending on the parameter values, changes barely in the two unitarization procedures. It is not a surprise since it is located far away from the unphysical left-hand cut in the on-shell factorization method and the difference between the two methods is of \({\mathcal {O}}\big ((s-s_\text {thr})^3\big )\). Similar to the on-shell factorization of the BSE case, no other poles are found for the single-channel cases.

4.2 Coupled-channel cases

In this subsection, we investigate poles of the VV scattering amplitudes in the coupled-channel cases using the N / D method. For the n-channel case, there are \(2^n\) Riemann sheets (1 physical Riemann sheet and \(2^n-1\) unphysical ones) in total. In addition to the bound state poles on the physical sheet, poles may also appear on the unphysical ones. The continuation to the unphysical Riemann sheets for coupled-channels is given by the matrix form of Eq. (34), where the \(\rho (s)\) is a diagonal matrix \(\rho (s)=\text {diag}\{N_i\rho _i(s)\}\) with i the channel index and \(N_i=0\) and 1 representing the physical and unphysical sheets for the \(i\text {th}\) channel. It is easy to see that the \(2^n\) Riemann sheets correspond to the various choices of the set \(N_i\). In this section, we only consider the poles which have significant impact on the physical observables in a specific energy region. In Table 3, we collect the poles in the energy region of interest for the coupled-channel calculations using different values of coupling g and cutoff \(q_\text {max}\). Nevertheless, it is possible to find unphysical poles whose distance to the relevant thresholds is larger than \(250~\mathrm {MeV}\) with an imaginary part larger than 200 MeV on the physical sheet for \(J=2\) sectors due to the perturbative treatment of the N(s) functions. Such poles exist as long as there is no bound state pole, as required for a nontrivial holomorphic function.Footnote 6 This kind of poles does not appear for \(J=0\) and \(J=1\) sectors. This is due to the fact that the contribution from the on-shell approximation of exchanged diagrams to the N functions for \(J=2\) sectors are significantly larger than those for \(J=0\) and \(J=1\) sectors, see e.g. Fig. 4 in Ref. [36]. Notice that any pole in the physical Riemann sheet other than the bound state ones violates causality (see, e.g., [59]). To overcome such an unsatisfactory situation, without knowing exactly the discontinuity along the left-hand cuts, so that they can be treated nonperturbatively,Footnote 7 we exclude those poles with an imaginary part more than \(200~\mathrm {MeV}\) and the distance to each threshold more than \(250~\mathrm {MeV}\) by hand as done in Refs. [61, 62].

A comparison of the poles obtained in this work with those in Ref. [45] using the nonrelativistic limit is presented in Table 4, together with the possible assignments to the mesons listed in the Review of Particle Physics by the Particle Data Group (PDG) [29]. We find a bound state pole in the \((S,I,J)=(0,0,0)\) system, which is absent in the on-shell factorization method, and it is shown in the left panel of Fig. 8. The pole is located between 1.4 and 1.5 GeV, and it might be significant to form the scalar meson \(f_0(1370)\) or \(f_0(1500)\) [29]. It is consistent with the pole found in the SU(2) case [36] and in the nonrelativistic limit in Ref. [45], see Table 4. One may wonder about the reliability of this pole since it is about 0.6 GeV below the \(\phi \phi \) threshold while the subtraction constants in \(D(s)_{55}\), where 5 labels the \(\phi \phi \) channel, are fixed by matching at the \(\phi \phi \) threshold via Eq. (32). To investigate this issue, we calculate its residues which correspond to the products of its couplings to various channels, i.e.,

with i the channel index and \(g_i\) the corresponding effective coupling constant. It turns out that this bound state pole couples most strongly to the \(\rho \rho \) channel (dominant channel) and the channels with higher thresholds are negligible. In addition, using \(g=4.618\) and \(q_\text {max}=0.875\) GeV a pole located at \((1.73\pm 0.02\,i)\) GeV is found on an unphysical Riemann sheet. In Ref. [45], the corresponding pole is at \((1.726\pm 0.028\,i)\) GeV, and is assigned to the \(f_0(1710)\) scalar meson. It is not surprising that the two pole positions are similar since the threshold of the dominant channel \(K^*\bar{K}^*\) is close to the pole, and thus the nonrelativistic limit in Ref. [45] is a good approximation. Nevertheless, we find a sizable dependence of the pole position on the coupling and cutoff values, see Table 3.

The poles we obtained in the scalar and vector sectors of \((S,I)=(0,0)\) are consistent with the nonrelativistic results in Ref. [45], see Table 4. In Ref. [45], two bound state poles are reported in the tensor sector, which couple dominantly to \(\rho \rho \) and \(K^*\bar{K}^*\) and are assigned to the \(f_2(1270)\) and \(f_2^\prime (1525)\) resonances, respectively.Footnote 8 However, no such poles are found in our calculation in this (0, 0, 2) channel, see the right panel of Fig. 8, which agrees with the SU(2) relativistic result in Ref. [36]. We also want to point out that although we exclude by hand the remote region on the physical Riemann sheet from the applicability of our treatment, see discussions at the beginning of this subsection, there is not any trend for the emergence of a bound state pole all the way from the \(\rho \rho \) threshold to around 1270 MeV, see Fig. 8. We thus regard the absence of tensor bound state poles as a reliable conclusion. To investigate more quantitatively possible poles beyond the near-threshold region, a more rigorous and complete treatment to the left-hand cuts is required. Also, a more realistic vector-vector interaction beyond the leading order hidden local symmetry Lagrangian (2) is needed, which do not seem to be available in the near future.

For the \((S,I,J)=(1,1/2,0)\) system, a pole around 1.6 GeV coupled dominantly to \(\rho K^*\) is found, which corresponds to the bound state pole at \((1.643\pm 0.047\,i)\) GeV in Ref. [45]Footnote 9. However, for the \((S,I,J)=(1,1/2,2)\) tensor sector, we do not find a bound state pole corresponding to the one at (\(1.431\pm 0.001i\)) GeV in Ref. [45], see the right panel of Fig. 9.

So far we have neglected the widths of the vector mesons. A convolution of the loop integrals with the vector-meson spectral functions, accounting for the contributions from the decays \(\rho \rightarrow \pi \pi \) and \(K^*\rightarrow \pi K\), will give a width to the bound states and increase the width of resonances. In addition, box diagrams with four intermediate pseudoscalar mesons contribute to the widths as well, corresponding to the decays into two pseudoscalar mesons. In order to include such contributions, one has to introduce model-dependent form factors, and the widths strongly depend on the cutoff one uses in the form factors. However, the real part of the pole positions are merely affected [35, 36, 45]. Since we are only interested in the existence of poles, we therefore do not introduce the convolution of loop functions and the box diagrams in this work.

5 Summary

In Ref. [36], the first-iterated N / D method was proposed to the \(\rho \rho \) interaction and possible dynamically generated resonances, and no tensor bound state poles reported in the nonrelativistic calculation [35] were found. In this method, poles of the T-matrix correspond to zeros of the D(s) function, which does not have any left-hand cut. Thus, contrary to the claim in Ref. [42], the disappearance of the tensor bound state poles is not due to the unphysical left-hand cuts, but due to the energy-dependence of the potential.

In this paper, we extend the method to coupled channels for the S-wave interactions for the whole vector-meson nonet. The possible dynamically generated resonances (including bound states) are listed in Table 4. Contrary to the results in the nonrelativistic treatment [45], we did not find any bound state poles in tensor sectors with \(I(J^P)=0(2^+)\) and \(1/2(2^+)\), confirming the single-channel result for the \(\rho \rho \) case in Ref. [36].

In this work, the left-hand cut is considered perturbatively. In addition, the contributions from the large widths of the \(\rho \) and the \(K^*\), as well as the channels with a pair of pseudoscalar mesons, are not considered. The inclusion of such contributions will increase the widths of the generated states. The results in this work are phenomenologically valuable to understand which mesonic resonances owe their existence mainly due to the interactions between a pair of vector mesons.

Notes

The left-hand cut \(s\le 3 M_\rho ^2\) develops when the Mandelstam variable \(t\ge M_\rho ^2\), corresponding to the fact that the \(\rho \) can be exchanged in the t-channel. This left-hand cut is manifest in the tree-level potential as well as in the full T-matrix.

However, the scalar and tensor potentials have the same energy dependence in Ref. [42] (see Table I) and thus have the same effective range.

Note that we use an older value here for a better comparison with the earlier results.

For the S-wave, the C parity of the \(K^*\bar{K}^*\) system with \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\) is negative. The system does not couple to the \(\omega \phi \), whose quantum numbers are \((S,I,J)=(0,0,1)\) as well, since the C parity of the latter must be positive.

Notice that the pole has an imaginary part in Ref. [45] because the width of the \(K^*\) is taken into account by convolving the loop integral with the \(K^*\) spectral function.

They are not harmful as long as they are located far from the relevant energy region (beyond the applicable range of the theory).

Recently, the left-hand cuts are treated nonperturbatively in the N / D method for the S-wave nucleon-nucleon scattering in Ref. [60].

Notice that at 1.27 GeV the binding momentum of the \(\rho \rho \) system is around 0.44 GeV, and at 1.53 GeV the binding momentum of the \(K^*{\bar{K}}^*\) system is around 0.45 GeV.

Note that the imaginary part is due to the convolution of the loop integrals with the spectral functions of the vector mesons in Ref. [45].

References

S. Weinberg, Phys. A 96, 327 (1979)

J. Gasser, H. Leutwyler, Ann. Phys. 158, 142 (1984)

J. Gasser, H. Leutwyler, Nucl. Phys. B 250, 465 (1985)

S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. 166, 1568 (1968)

S.R. Coleman, J. Wess, B. Zumino, Phys. Rev. 177, 2239 (1969)

C.G. Callan Jr., S.R. Coleman, J. Wess, B. Zumino, Phys. Rev. 177, 2247 (1969)

G. Ecker, J. Gasser, A. Pich, E. de Rafael, Nucl. Phys. B 321, 311 (1989)

G. Ecker, J. Gasser, H. Leutwyler, A. Pich, E. de Rafael, Phys. Lett. B 223, 425 (1989)

R. Bavontaweepanya, X.-Y. Guo, M.F.M. Lutz, Phys. Rev. D 98(5), 056005 (2018). arXiv:1801.10522 [hep-ph]

D. Djukanovic, M.R. Schindler, J. Gegelia, G. Japaridze, S. Scherer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 122002 (2004). arXiv:hep-ph/0407239

I. Rosell, J.J. Sanz-Cillero, A. Pich, JHEP 0408, 042 (2004). arXiv:hep-ph/0407240

P.C. Bruns, U.-G. Meißner, Eur. Phys. J. C 40, 97 (2005). arXiv:hep-ph/0411223

J.J. Sakurai, Currents and Mesons (The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1969)

S. Gasiorowicz, D.A. Geffen, Rev. Mod. Phys. 41, 531 (1969)

M. Bando, T. Kugo, S. Uehara, K. Yamawaki, T. Yanagida, Phys. Rev. Lett. 54, 1215 (1985)

M. Bando, T. Kugo, K. Yamawaki, Nucl. Phys. B 259, 493 (1985)

K. Kawarabayashi, M. Suzuki, Phys. Rev. Lett. 16, 255 (1966)

Riazuddin, Fayyazuddin, Phys. Rev. 147, 1071 (1966)

U.-G. Meißner, Phys. Rept. 161, 213 (1988)

M. C. Birse, Z. Phys. A 355 (1996) 231. arXiv:hep-ph/9603251

A.M. Badalyan, L.P. Kok, M.I. Polikarpov, YuA Simonov, Phys. Rept. 82, 31 (1982)

J. A. Oller and E. Oset, Nucl. Phys. A 620 (1997) 438 Erratum: (Nucl. Phys. A 652 (1999) 407). arXiv:hep-ph/9702314

J.A. Oller, U.-G. Meißner, Phys. Lett. B 500, 263 (2001). arXiv:hep-ph/0011146

N. Kaiser, P. B. Siegel, W. Weise, Nucl. Phys. A 594 (1995) 325. arXiv:nucl-th/9505043

E. Oset, A. Ramos, Nucl. Phys. A 635 (1998) 99. arXiv:nucl-th/9711022

R.H. Dalitz, S.F. Tuan, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2, 425 (1959)

D. Jido, J. A. Oller, E. Oset, A. Ramos, U.-G. Meißner, Nucl. Phys. A 725 (2003) 181. arXiv:nucl-th/0303062

F.-K. Guo, C. Hanhart, U.-G. Meißner, Q. Wang, Q. Zhao, B.-S. Zou, Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015004 (2018). arXiv:1705.00141 [hep-ph]

M. Tanabashi et al., Particle Data Group. Phys. Rev. D 98, 030001 (2018)

H.Y. Lu, CLAS Collaboration. Phys. Rev. C 88, 045202 (2013). arXiv:1307.4411 [nucl-ex]

M. Albaladejo, P. Fernandez-Soler, F.-K. Guo, J. Nieves, Phys. Lett. B 767, 465 (2017). arXiv:1610.06727 [hep-ph]

M.-L. Du, M. Albaladejo, P. Fernandez-Soler, F.-K. Guo, C. Hanhart, U.-G. Meißner, J. Nieves, D.-L. Yao, Phys. Rev. D 98(9), 094018 (2018). arXiv:1712.07957 [hep-ph]

L. Liu, K. Orginos, F.-K. Guo, C. Hanhart, U.-G. Meißner, Phys. Rev. D 87, 014508 (2013). arXiv:1208.4535 [hep-lat]

R. Aaij, LHCb Collaboration. Phys. Rev. D 94, 072001 (2016). arXiv:1608.01289 [hep-ex]

R. Molina, D. Nicmorus, E. Oset, Phys. Rev. D 78, 114018 (2008). arXiv:0809.2233 [hep-ph]

D. Gülmez, U.-G. Meißner, J.A. Oller, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 460 (2017). arXiv:1611.00168 [hep-ph]

D.B. Lichtenberg, Unitary symmetry and elementary particles (Academic Press, New York, 1978)

M. Koll, R. Ricken, D. Merten, B.C. Metsch, H.R. Petry, Eur. Phys. J. A 9, 73 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/0008220

R. Ricken, M. Koll, D. Merten, B.C. Metsch, H.R. Petry, Eur. Phys. J. A 9, 221 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/0008221

L.-Y. Dai, M.R. Pennington, Phys. Rev. D 90, 036004 (2014). arXiv:1404.7524 [hep-ph]

T. Mori, Belle Collaboration. J. Phys. Soc. Jap. 76, 074102 (2007). arXiv:0704.3538 [hep-ex]

L.-S. Geng, R. Molina, E. Oset, Chin. Phys. C 41, 124101 (2017). arXiv:1612.07871 [nucl-th]

L.D. Landau, Nucl. Phys. 13, 181 (1959)

S. Coleman, R.E. Norton, Nuovo Cim. 38, 438 (1965)

L.-S. Geng, E. Oset, Phys. Rev. D 79, 074009 (2009). arXiv:0812.1199 [hep-ph]

Z.-H. Guo, J.A. Oller, J. Ruiz de Elvira, Phys. Rev. D 86, 054006 (2012). arXiv:1206.4163 [hep-ph]

T. Inoue, E. Oset, M. J. Vicente Vacas, Phys. Rev. C 65 (2002) 035204. arXiv:hep-ph/0110333

C. Garcia-Recio, J. Nieves, E. Ruiz Arriola, M.J. Vicente Vacas, Phys. Rev. D 67 (2003) 076009. arXiv:hep-ph/0210311

T. Hyodo, W. Weise, Phys. Rev. C 77, 035204 (2008). arXiv:0712.1613 [nucl-th]

M.-L. Du, F.-K. Guo, U.-G. Meißner, D.L. Yao, Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 728 (2017). arXiv:1703.10836 [hep-ph]

J.A. Oller, E. Oset, Phys. Rev. D 60, 074023 (1999). arXiv:hep-ph/9809337

J. A. Oller, E. Oset, J. R. Peláez, Phys. Rev. D 59 (1999) 074001 Erratum: [Phys. Rev. D 60 (1999) 099906] Erratum: [Phys. Rev. D 75 (2007) 099903]. arXiv:hep-ph/9804209

F.-K. Guo, R.-G. Ping, P.-N. Shen, H.-C. Chiang, B.-S. Zou, Nucl. Phys. A 773, 78 (2006). arXiv:hep-ph/0509050

G.F. Chew, S. Mandelstam, Phys. Rev. 119, 467 (1960)

J.D. Bjorken, Phys. Rev. Lett. 4, 473 (1960)

L. Castillejo, R.H. Dalitz, F.J. Dyson, Phys. Rev. 101, 453 (1956)

H. Pierre Noyes, Phys. Rev. 119 (1960) 736

Z.-H. Guo, J.A. Oller, G. Ríos, Phys. Rev. C 89, 014002 (2014). arXiv:1305.5790 [nucl-th]

V. Gribov, Y. Dokshitzer, J. Nyiri, Strong Interactions of hadron at high energies: Gribov lectures on theoretical physics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009)

D.R. Entem, J.A. Oller, Phys. Lett. B 773, 498 (2017). arXiv:1610.01040 [nucl-th]

B. Borasoy, U.-G. Meißner, R. Nißler, Phys. Rev. C 74, 055201 (2006). arXiv:hep-ph/0606108

M. Mai, U.-G. Meißner, Nucl. Phys. A 900, 51 (2013). arXiv:1202.2030 [nucl-th]

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through funds provided to the Sino–German Collaborative Research Center “Symmetries and the Emergence of Structure in QCD” (NSFC Grant No. 11621131001, DFG Grant No. TRR110), by the NSFC (Grant No. 11747601), by the Thousand Talents Plan for Young Professionals, by the CAS Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences (Grant No. QYZDB-SSW-SYS013), by the CAS Key Research Program (Grant No. XDPB09), by the CAS Center for Excellence in Particle Physics (CCEPP), by the by the CAS President’s International Fellowship Initiative (PIFI) (Grant No. 2018DM0034), and by VolkswagenStiftung (Grant No. 93562).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Du, ML., Gülmez, D., Guo, FK. et al. Interactions between vector mesons and dynamically generated resonances. Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 988 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-6475-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-6475-8