Abstract

We investigate the search prospects for new scalars beyond the standard model at the large hadron collider (LHC). In these studies two real scalars S and \(\chi \) have been introduced in a two Higgs-doublet model (2HDM), where S is a portal to dark matter (DM) through its interaction with \(\chi \), a DM candidate and a possible source of missing transverse energy (\(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\)). Previous studies focussed on a heavy scalar H decay mode \(H \rightarrow h\chi \chi \), which was studied using an effective theory in order to explain a distortion in the Higgs boson (h) transverse momentum spectrum (von Buddenbrock et al. in arXiv:1506.00612 [hep-ph], 2015). In this work, the effective decay is understood more deeply by including a mediator S, and the focus is changed to \(H \rightarrow h S,~SS\) with \(S \rightarrow \chi \chi \). Phenomenological signatures of all the new scalars in the proposed 2HDM are discussed in the energy regime of the LHC, and their mass bounds have been set accordingly. Additionally, we have performed several analyses with final states including leptons and \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\), with \(H \rightarrow 4 W\), \(t(t)H \rightarrow 6 W\) and \(A \rightarrow ZH\) channels, in order to understand the impact these scalars have on current searches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In light of the discovery of a Higgs-like scalar [1–6] at the large hadron collider (LHC), there have been many studies devoted to understanding the scalar’s properties and couplings to standard model (SM) particles. In general, two lines of investigation have been pursued: (a) experimental analyses to closely examine if the behaviour of this scalar reveal any discrepancy with predictions of the SM, and (b) theoretical studies on how any new physics – both model-dependent and independent – can be discerned. The ‘new physics’ possibilities in this context often stress the possible presence of additional scalars which may participate in electroweak symmetry breaking (EWSB). As such, searches for new scalars, neutral and/or charged, are continuously being carried out in various channels by both the ATLAS and the CMS collaborations.

There are many possible theoretical models which contain additional scalars. Some of the simplest such models are the two-Higgs-doublet models (2HDMs) [7, 8]. However, there are a range of issues with these models, such as the generation of neutrino masses that can accommodate a 125 GeV scalar, especially for supersymmetric models [9]. This includes Higgs-like scalars belonging to representations of SU(2), which are not necessarily doublets. Furthermore, the source of dark matter (DM) in the universe remains unresolved, and many hypotheses have been put forward in an attempt to explain its origin and existence [10].

If any new physics exists in the scalar sector (especially within the reach of the LHC) it should be observed by the experimental collaborations in the near future. With this in view, possible sources of deviation from the SM could be inferred by looking at fiducial Higgs production cross sections and differential distributions [11–15]. Several of the distributions in this area of study – most notably the Higgs boson transverse momentum (\(p_\text {T}\)) spectrum – are sensitive to new physics predictions, and it is an interesting study to identify if new physics models can provide a compatible description of the data.

The present work is an effort in this direction, where we shall study the model-dependence and independence of a Type-II inspired 2HDM. Our addition to the standard 2HDM shall be to include a singlet scalar, \(\chi \), which is made odd under a \({\mathbb Z}_2\) symmetry (and is thus stable for qualification as a DM candidate). In a previous study [16], the heavier CP-even neutral scalar H was assumed to have a large branching ratio (BR) in the channel \(H \rightarrow h\chi \chi \) (where h is the 125 GeV Higgs boson) in order to fit the data. This can be facilitated through the on-shell participation of our additional scalar S in the decay of H. The transformation from the effective vertex approach to the S mediated approach can be seen in Fig. 1 – this is detailed in Sect. 2. The terms in the Lagrangian involving \(\chi \) and S have been included here as effective interaction terms in addition to the Lagrangian of a Type-II 2HDM [17].

The paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2 we discuss a 2HDM inspired formalism in brief, and then discuss an effective model in Sect. 3, by which the Higgs boson \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum can be studied. Phenomenological signatures of the new scalars and particles are analysed in Sects. 4 and 5. Our findings are then summarised and discussed in Sect. 6.

2 Framework

In this section we briefly discuss the 2HDM with its basic particle content, which we then extend to a Type-II 2HDM. For a more recent review of the constraints in detail, we refer the reader to Ref. [8]. We then introduce two real scalars in this particular Type-II 2HDM, \(\chi \) and S, where \(\chi \) will be treated as a DM candidate, while S is similar to the SM Higgs boson.

The complete Lagrangian for a 2HDM can be written as

where \(\Phi _1\) and \(\Phi _2\) are two complex \(SU(2)_L\) doublet scalar fields. \({\mathscr {L}}_\mathrm{int}\) contains all possible interaction terms, including the SM Lagrangian. \({\mathscr {V}}\left( \Phi _1, \Phi _2\right) \) is the most general remormalisable scalar potential of the 2HDM and may be written as

This potential has terms multiplying the parameters \(m_{12}\), \(\lambda _5\), \(\lambda _6\) and \(\lambda _7\), which in general are complex and, hence, are sources of CP violation. The other terms in the potential are real. It is also noted that all these parameters appearing in the general potential are not observable, since they can be modified by a change of basis.

After spontaneous EWSB, five physical Higgs particles are left in the spectrum: one charged Higgs pair, \(H^\pm \), one CP-odd scalar, A, and two CP-even states, h and H – where by convention \(m_H>m_h\). Here \(\phi _i^+\) and \(\phi _i^0\) denote the \(T_3=1/2\) and \(T_3=-1/2\) components of the ith doublet for \(i = 1, 2\). The angle \(\alpha \) diagonalises the CP-even Higgs squared-mass matrix and \(\beta \) diagonalises both the CP-odd and the charged Higgs sectors, which leads to \(\tan \beta = v_2/v_1\). Note here that \(\langle \phi _i^0 \rangle = v_i\) for \(i = 1, 2\) and \(v_1^2 + v_2^2 = v^2 \approx (246\,\text {GeV})^2\), where v is the physical vacuum expectation value (vev). Further choices of symmetries and couplings to quarks and leptons etc. can be made, which lead to different types of models. Models which lead to natural flavour conservation are called Type-I, Type-II, Lepton-specific or Flipped 2HDMs, as detailed in Ref. [8]. In our studies we used a Type-II 2HDM, upon which we added our additional scalars.

In Ref. [18], a study has been carried out considering two benchmark scenarios of a 2HDM and minimal supersymmetric model, whereby exclusion contours are given on the model parameters using CMS Run 1 data. By fixing the lighter Higgs mass, \(m_h = 125.09\) GeV, \(m_A = m_H + 100\) GeV, \(m_{H^\pm } = m_H + 100\) GeV, \(m_H\) and \(\tan \beta \) is scanned. The Type-I (II) 2HDM parameter space is generally constrained such that \(\cos \left( \beta - \alpha \right) \lesssim 0.5 (0.2)\), \(m_H \lesssim 380 ({\approx }380)\) and \(\tan \beta \lesssim 2\) (all). These constraints have been obtained by considering the decay channels \(A/H/h \rightarrow \tau \tau \) [19], \(H\rightarrow WW/ZZ\) [20], \(A\rightarrow ZH(llbb)\) and \(A\rightarrow ZH(ll\tau \tau )\) [21].

Any extended theory beyond the SM must preserve and respect the known symmetries and constraints from theory as well as observations from experiments. Accordingly, the following constraints apply to a 2HDM:

-

(a)

Vacuum stability: the Higgs potential must be bounded from below and therefore the following conditions for \(\lambda _m\) must be satisfied:

(3)

(3) -

(b)

Perturbativity: we need the bare quartic couplings in the Higgs potential to satisfy perturbativity as \(\left| \lambda _m\right| < 4\pi \) for \(m = 1,2,\ldots ,7\). In addition, the magnitudes of quartic couplings among physical scalars \(\lambda _{\phi _i \phi _j \phi _k \phi _l}\) should also be smaller than \(4\pi \), where \(\phi _i = h, H, A, H^\pm \).

-

(c)

Oblique parameters: the electroweak precision observables such as the S, T and U parameters obtain contributions from extra scalars in the 2HDM in loop calculations, and therefore receive contributions from \(\Delta S\), \(\Delta T\) and \(\Delta U\).

-

(d)

In addition, there are also some experimental constrains such as LEP bounds, flavour-changing neutral current (FCNC) constraints, Higgs data from the LHC etc. that can restrict the model parameters.

Recent studies on the 2HDM with its phenomenology and constraints can be found in Refs. [22–24]. In general, all multi-Higgs-doublet models including 2HDMs contain the possibility of severely constrained tree level FCNCs. To avoid these potentially dangerous interactions one can impose several discrete symmetries in many possible ways. One such discrete symmetry to avoid FCNCs is \(\mathbb {Z}_2\), which demands invariance of the general scalar potential under the transformations \(\Phi _1 \rightarrow -\Phi _1\) and \(\Phi _2 \rightarrow \Phi _2\). However, this discrete \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry could be (a) exact if \(m_{12}\), \(\lambda _6\) and \(\lambda _7\) vanish, and thus the scalar potential will be CP conserving, (b) broken softly if it is violated in the quadratic terms only, i.e., in the limit where \(\lambda _6\), \(\lambda _7\) vanish, but \(m_{12}\) remains non-zero and (c) hard breaking, if it is broken by the quadratic terms too, where the parameters \(m_{12}\), \(\lambda _6\) and \(\lambda _7\) are all non-vanishing.

In a Type-II 2HDM the discrete \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry applies for \(\Phi _1 \rightarrow -\Phi _1\) and \(\psi ^a_R \rightarrow -\psi ^a_R\), where \(\psi ^a_R\) are the charged leptons or down type quarks, and a represents the generation index. However, in our studies the terms associated with \(\lambda _6\) and \(\lambda _7\) are neglected and \(m_{12}\) is taken as real. The quadratic couplings in terms of the physical masses of the CP-even scalars (\(m_h\), \(m_H\)), the CP-odd scalar (\(m_A\)) and charged scalars (\(m_{H^\pm }\)) can be expressed as:

In Appendix A and Appendix B we provided the analytical expressions for production cross sections of H and A, and the interaction Lagrangians in a Type-II 2HDM, respectively.

2.1 Adding a scalar \(\chi \)

In order to accommodate some features in the Run 1 ATLAS and CMS results viz. (a) the measurement of the differential Higgs boson \(p_\text {T}\), (b) di-Higgs resonance searches, (c) top associated Higgs production and (d) VV resonance searches (where \(V = Z, W^\pm \)), in Ref. [16] it was assumed that at least one Higgs boson is produced due to the decay of a heavy scalar H in association with a DM candidate \(\chi \). However, it was explained in an effective theory which is briefly discussed in the next section. In this work, we consider the accommodation of H in \(\chi \) in a complete theory. The addition of \(\chi \) as a real scalar in the 2HDM model requires additional terms in the potential defined in Eq. 2. One can consider \(\chi \) as a gauge-singlet scalar and a stable DM candidate if its mixing with the doublets \(\Phi _1\) and \(\Phi _2\) can be prevented by the introduction of some discrete symmetry. One such symmetry is a \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) under which \(\chi \) is odd and all other fields are even. This also ensures the stability of \(\chi \). Thus, the most general potential consistent with the gauge and \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetries can be written as

Here we shall consider the hard breaking of this \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry, with \(\lambda _{\chi _{3}}\) being real. In the case of a soft breaking of the symmetry, the term \(\lambda _{\chi _{3}}\) and corresponding terms in \({\mathscr {V}}\left( \Phi _1,\Phi _2\right) \) with \(\lambda _6\) and \(\lambda _7\) will disappear. Despite the fact that any additional scalar to the 2HDM potential may acquire a vev, we explicitly consider the case where the additional field \(\chi \) does not acquire a vev. Hence, in terms of the mass eigenstates, the complete interaction terms with h, H, A and \(H^\pm \) will be

where the couplings are given as

It is also noted that \({\mathscr {L}}_\chi \) does not include A–\(\chi \)–\(\chi \) interaction terms due to CP violation issues, but in principle the CP-odd scalar A plays an important role in determining the DM relic density through the creation or annihilation process \(\chi \chi \leftrightarrow AA\).

In addition to the constraints discussed for the 2HDM parameters, the perturbativity conditions also imply \(| \lambda _{\chi _m} | < 4\pi \) for \(m=1,2,3\). The coupling \(\lambda _{\chi _4}\) for the \(\chi ^4\) term should be \(0< \lambda _{\chi _4} < 4 \pi \), where the lower limit is required for stability. Vacuum stability requires the following necessary and sufficient conditions in addition to Eq. 3, so that the potential \({\mathscr {V}}(\Phi _1,\Phi _2,\chi )\) must be bounded from below:

If \(\lambda _{\chi _1}, \lambda _{\chi _2}, \lambda _{\chi _3} < 0\), then the additional conditions should also satisfy

In order to ensure a stable DM candidate \(\chi \), we need to have an additional condition that the vev, \(\langle \chi \rangle \), should vanish at the global minimum of the scalar potential in Eq. 9. This can be obtained numerically such that \(\langle \chi \rangle = 0\), \(\langle \Phi _1 \rangle \ne 0\) and \(\langle \Phi _2 \rangle \ne 0\). Practical studies and analyses on the model follow these constraints with \(m_\chi < m_h/2\). In Ref. [25] a similar study can be found.

In this work we consider \(\chi \) to be a scalar. However, while considering various features in the data, this may not be an appropriate assumption. In light of this, it is important to characterise \(\chi \) in terms of other possible theories. This could shed light on the production mechanisms and decay modes for H and A through gg and \(\gamma \gamma \), since they are loop induced processes. It is possible for \(\chi \) to run in these loops, and this could explain an enhancement of these rates. This would imply that \(\chi \) is a massive coloured fermion.

Simple possibilities for these extra fermions may be:

-

a single vector-like quark of charge 2/3,

-

an isospin doublet of vector-like quarks of charges 2/3 and −1/3,

-

an isodoublet and two singlet quarks of charges 2/3 and −1/3, or

-

a complete vector-like generation including leptons as well as quarks.

In this respect we should consider all four possible characteristics of \(\chi \) being a vector-like fermion (VLF). Similar studies can follow for the \(W^\pm \) and Z related decay modes of A.

Representative Feynman diagrams to study the Higgs boson \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum using the effective Lagrangian approach described by Eqs. (37) and (44). On the left through the quartic \(\lambda _{hH\chi \chi }\) vertex and on the right due to an additional scalar S, as described in text. Equivalence between two procedures can explain the strength of the coupling \(\lambda _{Hh\chi \chi }\) under a replacement with \(\lambda _{HhS}\) and \(\lambda _{S\chi \chi }\)

2.2 Adding a Higgs-like CP-even scalar S

Previously we discussed the inclusion of a real scalar \(\chi \) and accordingly its new interactions will appear in a 2HDM. Similarly, one can introduce a real scalar S, which is chosen to be similar to the SM Higgs boson with the allowed mass range \(m_S \in [m_h, m_H-m_h]\). S was initially introduced as a mediator to explain the \(H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \) decay mode, as shown in Fig. 1, however, it can be used to probe more interesting physics. For simplicity we can impose a \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry for \(S \rightarrow -S\) transformations, but this can also be relaxed for other implications in the theory. While introducing \(\chi \) in the 2HDM, we only consider its couplings with the scalars of this model i.e. h, H, A and \(H^\pm \). But in the case of S, which is SM Higgs-like, it is allowed to couple with all of the SM particles as well as \(\chi \). This is phenomenologically interesting for two reasons. First of all, S can be thought of as a portal between which SM particles can interact with DM. Second, the Higgs-like nature of S drastically reduces the number of free parameters in the theory, since all of the BRs to SM particles (and hence coupling strengths) are fixed to what a SM Higgs boson would have, scaled down appropriately by the introduction of an invisible decay mode \(S\rightarrow \chi \chi \). Since a large invisible BR is not experimentally observed for h, we can rather explore DM interactions with S.

It is clear that in the absence of such interactions, one should not expect any interesting physics. But mixing with SM particles along with other scalars of the 2HDM has two different consequences. First, S could be observed as a resonance through \(p p \rightarrow S \rightarrow VV\) modes, where \(V = Z, W^\pm ,~\gamma \). For a Higgs-like S, such searches would be similar to generic Higgs boson searches at higher masses, and the signal and background modelling would therefore be the same. However, it should be noted that in this study we consider direct production of S to be small, and S is produced dominantly through the decay of H. Second, it alters the coupling strengths of known interactions in the theory – for example, in a 2HDM there follows a sum rule for the neutral scalar gauge couplings \(g_{hWW}^2 + g_{HWW}^2\), which is the same as the SM coupling squared [26]. This sum rule will be violated if there is any mixing occurring between S and the doublets \(\Phi _{1,2}\), which will directly alter the expected projected bounds of 2HDM couplings.

In light of this, we add a realFootnote 1 scalar S considering the possibility of a discrete symmetry under \(S \rightarrow -S\). The parameters are arranged in such a way so that S acquires a vev. Without the discrete symmetry, the most general potential for S can be written as:

Now, if we impose a \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry for transformations of the form \(S \rightarrow -S\) (and all other fields are even), then the terms with the coefficient \(\mu _i\) (\(i = 1, 2, 3, S \)) will vanish in the above general potential. If we further assume another \(\mathbb {Z}_2^{'}\) symmetry for the transformations \(h\rightarrow h\), \(H\rightarrow -H\) and \(S\rightarrow S\), then the \(\lambda _{S_3}\) term will also vanish. This also eliminates \(\lambda _6\) and \(\lambda _7\) from \({\mathscr {V}}(\Phi _1,\Phi _2)\). However, we assume a soft breaking of \(\mathbb {Z}_2^{'}\), which allows for \(m_{12}^2\ne 0\). In the case where S does not acquire a vev (similar to \(\chi \)). Then the S related interactions in the potential are given by

One can write various couplings in the potential in terms of \(\lambda _{S_1}\), \(\lambda _{S_2}\), \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) as follows:

In order to generate an effective \(hH\chi \chi \) type interaction from a full model with S, we need to allow a coupling hHS. This coupling can be generated from the hHSS interaction if S acquires a vev. Therefore, the S in our model will indeed acquire a vev and mix with h and H.

From Ref. [27], one can infer that hS mixing must be small if it exists, with an upper limit on the mixing squared at about 20 %. In the limit of zero mixing between h and S (as well as H and S), the expressions for various couplings are shown in Eqs. (27)–(32). Equation 28 tells us that the HSS coupling need not be small even in this limit, since \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \), which are the mixing angles from the doublet sector exclusively, are free parameters. If we turn on a mixing between S and the doublets, Eq. 28 will receive corrections through the additional mixing angle(s) introduced. However, in the case of small hS mixing, the correction will also be small, and the HSS coupling will still remain sizeable.

Therefore, we assume that the mixing of S with h is small enough (by interplay of various parameters in the potential) that it will not spoil any experimental bounds. The hHSS interaction can be thought of as a source of the required hHS coupling if we replace one S by its vev in the hHSS interaction.

3 An effective theory approach to explain the Higgs \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum

To explain distortions in the Higgs boson \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum, we can consider an effective Lagrangian approach with the introduction of two hypothetical real scalars, H and \(\chi \), which are beyond the SM (BSM) in terms of its particle spectrum – as discussed in Ref. [16]. This effective model can also be used to study other phenomenology associated with Higgs physics. The formalism considers heavy scalar boson production though gluon–gluon fusion (ggF), which then decays into the SM Higgs and a pair of \(\chi \) particles. As before, \(\chi \) is considered as a DM candidate and therefore a source of missing transverse energy (\(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\)).

The required vertices for these studies are

where \(\beta _g = y_{ttH}/y_{tth}\) is the scale factor with respect to the SM Yukawa top coupling for H, and it is therefore used to tune the effective ggF coupling. A similar factor \(\beta _V\) is used for VVH couplings. The complete set of these new interactions are added to the SM Lagrangian, \({\mathscr {L}_{\text {SM}}}\), and thus the final Lagrangian is \(\mathscr {L} = \mathscr {L}_{\text {SM}} + \mathscr {L}_{\text {BSM}}\), where \(\mathscr {L}_{\text {BSM}}\) contains the terms beyond the SM interactions which is given by

The impact of the effective decay process \(H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \) on the Higgs \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum. Under the BSM hypothesis of \(gg\rightarrow H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \) (solid lines), the spectrum is distorted with respect to the SM prediction (dashed line). These distributions were made using 50,000 events generated at leading order (LO) and showered in Pythia8 [29]. Three mass points of H are chosen for demonstration, and \(m_\chi =60~\text {GeV}\sim m_h/2\)

Here, we should note that \(\chi \) only interacts with the SM Higgs and the postulated heavy scalar H – not with the SM fermions and gauge bosons. We also require that \(\chi \) is stable by imposing the appropriate symmetry conditions which we described previously in Sect. 2.1. Since we assume \(\chi \) to be a DM candidate, there are non-negligible constraints on the associated parameters of the vertices that come from the relic density of DM and the DM-nuclei inelastic scattering cross sections. In addition to this, constraints arise from limits on the invisible BR of the SM Higgs boson. These leave a narrow choice of the mass of the DM candidate, \(m_\chi \sim m_h/2\), as well as the parameter \(\lambda _{h\chi \chi } \sim [0.0006-0.006]\). We also assume that \(m_H\) would lie in the range, \(2 m_h< m_H < 2 m_t\) to forbid the \(H\rightarrow t t\) decay, as well as keep the \(H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \) decay on-shell.

A comparative view of the Higgs \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum as described by the S-mediated interaction (solid lines) and the effective \(H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \) interaction (dashed line). In this case, \(m_H\) is fixed to 300 GeV and \(m_S\) is varied. The generator setup is similar to that in Fig. 2

In this study, if we consider the process \(pp \rightarrow H \rightarrow h\chi \chi \), then a distortion could be predicted in the intermediate range of the Higgs \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum. This comes from the recoil of h against a pair of invisible \(\chi \) particles, and the effect on the Higgs \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum can be seen in Fig. 2. On introducing the S to mediate the effective interaction, the kinematics for the effective theory will be similar to the full theory with a large width S at \(m_S=m_H/2\) (in the limit \(m_\chi \rightarrow m_h/2\)). The Higgs \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum arising from the S-mediated interaction can be seen in Fig. 3; three mass points have been chosen to demonstrate the effect of \(m_S\) on the spectrum. In order to choose appropriate values of associated couplings one must consider the constraints from all potential experimental signatures which the model predicts i.e. di-Higgs and di-boson production through the resonance H, and top associated H production (in comparison to top associated h production) etc.

In an effective field theory approach, we do not consider the actual origin of the \(Hh\chi \chi \) coupling. One can assume that this effective interaction is mediated by the scalar particle S which will then decay in the mode \(S\rightarrow \chi \chi \). This inclusion of S can open up various new possibilities in terms of search channels and phenomenology. In addition to the above studies, if we look over the di-Higgs production modes in different decay channels (such as\(\gamma \gamma b \bar{b}\) or \(b\bar{b} b \bar{b}\) with jets etc.), then the vertices defined above (in Eqs. (33)–(36)) will be modified appropriately with S as an intermediate scalar and not as a DM candidate.Footnote 2 With the mass range \(m_h \lesssim m_S \lesssim m_H - m_h\) and \(m_S > 2m_\chi \), new possibilities for the processes in these studies include \(pp \rightarrow H\rightarrow hS\) as well as \(pp \rightarrow H \rightarrow hh\), considering the available spectrum of \(m_S\) and the associated coupling parameters. There is a possibility to introduce a HSS vertex in the study, which participates further in a \(H \rightarrow S S\) decay channel (similar to \(H \rightarrow h h\)). An important feature to keep in mind is that all decay modes of S (i.e. S into jets, vector bosons, leptons, DM etc.) are possible.

Following the effective theory approach, and after EWSB, the Lagrangian for singlet real scalar S can be written as:

where

Here \(V, V^\prime \equiv g, \gamma , Z \,\text {or}\, W^\pm \) and \(W^\pm _{\mu \nu } = D_\mu W^\pm _\nu - D_\nu W^\pm _\mu \), \(D_\mu W^\pm _\nu = [ \partial _\mu \pm i e A_\mu ] W^\pm _\nu \). Other possible self interaction terms for S are neglected here since they are not of any phenomenological interest for our studies. Hence the total effective Lagrangian is

It is interesting to note that the choice of narrow mass range for S, \(m_S\in [m_h, m_H-m_h]\) provides an opportunity to see various phenomenological aspects of the model in contrast to h. A few examples include the \(S\rightarrow \chi \chi \) mode that predicts \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) in Higgs-like events, monojet searches through Sj, or di-jet events in association with \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) through \(S+\text {jets}\) decays. The mass range for S may help to understand rates for a Higgs-like scalar in different possible production or decay modes too. An important search (after the SM Higgs discovery) at the LHC could be for a scalar candidate S through resonance production in either of the di-boson decay channels, \(S \rightarrow VV,\) and \(S\rightarrow \gamma \gamma \).

If we perform more investigation on the effective terms considered in the above set of Lagrangians (most notably \({\mathscr {L}}_{_{HhS}}\)), then the terms hhS, hSS and HHS are less relevant for the phenomenology due to the choice of a narrow mass window of S. However, the two terms with HSS and HhS are important. The origin for the consideration of the intermediate real scalar S demands that these two terms can explain the large BR of \(H \rightarrow h\chi \chi \). In one sense, there is an equivalence of the couplings \(\lambda _{_{Hh\chi \chi }}\) with the cascade of \(\lambda _{_{HhS}}\) and \(\lambda _{_{S\chi \chi }}\), so that the 3 body decay can be equated to a series of 2 body decays, as shown in Fig. 1. On the other hand, in order to minimise the number of free parameters in the theory, we consider a ratio of couplings \(r = {| \lambda _{_{HSS}} |}/{| \lambda _{_{HhS}} |}\). This ratioFootnote 3 could be fixed in the limits of theoretically allowed values, and then either one of the couplings \(\lambda _{_{HSS}}\) or \(\lambda _{_{HhS}}\) can be varied to control the rates of the processes which are studied.

4 Phenomenology

The phenomenology discussed in the previous section (i.e. with H, S and \(\chi \) in an effective theory) can also be studied in a model-dependent way. In Sect. 2 we discussed the particle spectrum of a 2HDM with two real singlet scalars and their interactions in Type-II 2HDM scenarios, while also considering a specific \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry. Here we discuss various phenomenology associated with this particle spectrum applicable to collider signatures (in particular at the LHC). Given the mass range of each new scalar, their appropriate dominant decay modes have been listed in Table 1 as a reference for the discussion of the experimental signatures. An explicit list of experimental search channels is presented in Table 2.

4.1 Heavy scalar H

In Sect. 3, a heavy scalar H was introduced in an effective theory, with the primary goal explaining a distortion in the \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum of the Higgs boson. Considering the analyses performed with the effective theory approach, we can now think of H as the heavier CP-even component of a 2HDM.Footnote 4 Furthermore, our motive should then be to fit parameters such as \(\tan \beta \), \(\alpha \) and the masses of A and \(H^\pm \) in this specific model. However, the question arises as to whether we should think of a generalised 2HDM or any particular type of this model, as described in detail in Ref. [8]. On the other hand, we also need to consider experimental data from searches, which will affect the possible processes taken into consideration using this model.

Note that in this study, we explicitly choose that the lighter CP-even component of a 2HDM is the experimentally observed scalar (i.e. \(m_h = 125\) GeV). With this fixed, we choose the H mass to be in the range \(2 m_h< m_H < 2 m_t\) for reasons which were explained in Sect. 3.

In the simplest case, the cross section of \(gg\rightarrow H\) production (i.e. the dominant production mode) would be the same as a heavy Higgs boson – between 5 and 10 pb at \(\sqrt{s}=13\) TeV [28]. However, this number could be altered if one considers a rescaling of the Yukawa coupling or the possibility of extra coloured particles running in the loop (as alluded to above). In Ref. [16], the number \(\beta _g\) – which was assumed as a rescaling of the Yukawa coupling – was estimated to be around 1.5. This implies that the \(gg\rightarrow H\) production cross section could be enhanced by as much as a factor of 2.

4.2 CP-odd scalar A

Typically, experimental resonance searches hope to see excesses around a particular mass range (with the appropriate decay width approximation) in the invariant mass spectra of di-jet or di-boson final states. These spectra provide hints for new BSM particles to be discovered. The masses of these resonances \(m_\Phi \) (where for a 2HDM \(\Phi = H, A , H^\pm \)) might be of the order of \(2 m_h< m_\Phi < 2 m_t\) (which we considered in our previous studies for \(m_H\)) or beyond this order – perhaps \(2 m_t \ll m_\Phi < \mathscr {O}\)(1 TeV) or even \(m_\Phi \gg \mathscr {O}\)(1 TeV).

In terms of phenomenological aspects for a 2HDM CP-odd scalar A, the following salient features could be observed:

-

(1)

In 2HDMs masses of A and \(H^\pm \) are correlated. So if we wish to have a 2HDM with a particular mass \(m_A\), its compatibility with \(m_{H^\pm }\) should also be considered. With a known value of \(m_H\) (\(2 m_h< m_H < 2 m_t\)) and \(m_h = 125\) GeV, one should tune the parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) accordingly.

-

(2)

In the case of ggF production for A (through the ggA vertex), there will be a need for a scaling factor \(\beta _g^A\) (in a similar way to the treatment of H production, which scales with \(\beta _g\)). Considering the decay modes of A, \(A \rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) in particular needs another scaling factor \(\beta _\gamma ^A\). In this respect, one needs to control the \(H\rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) decay rates via another parameter \(\beta _\gamma \), since the form factors appearing in the calculation of \(gg \rightarrow H, A\) and \(H, A \rightarrow \gamma \gamma \) have a different structure. They are also dependent on the masses of the particles under consideration (this is described in Refs. [7, 17]). One should also study other possible decay modes of A which include pairs of \(W^\pm \) or Z bosons in the final state. These decays are possible only at loop level in 2HDMs, since \(AW^+W^-\) and AZZ couplings are absent as a result of CP conservation issues.

-

(3)

Depending on parameter choices, this model can predict an arbitrarily large amount of \(Z+\)jets\(+\) \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) events. It is important to think of the contribution of the decay mode of \(A \rightarrow Z H\), where \(H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \). This requires that \(m_A > m_Z + m_H\).

-

(4)

With respect to point (3), we can also consider different processes with multilepton final states through same-sign and opposite-sign lepton selection, in association with jets. This phenomenological interest arises from the inclusion of the charged bosons, \(H^\pm \).

-

(5)

Since the SM Yukawa couplings for top quarks, \(y_{tth}\), are well known, one will need to adjust the parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) in such a way so that \(y_{ttA}\) and \(y_{ttH}\) must follow the appropriate branchings for \(A\rightarrow t \bar{t}\) and \(H \rightarrow t \bar{t}\). It should be noted here that since \(y_{tth}\) is close to unity (due to large top-quark mass), it can also add insight into new physics scales.

4.3 Charged scalars \(H^\pm \)

In the 2HDM particle spectrum, we also have the possibility of charged bosons, \(H^\pm \), which can be produced at the LHC. Searches for these particles most often consider production cross sections and BRs in different decay channels. The prominent decay modes of \(H^{\pm }\) are \(H^\pm \rightarrow tb\) and \(H^\pm \rightarrow W^\pm h\) when \(m_{H^\pm } > m_t\). Since we consider \(2 m_h< m_H < 2 m_t\), the decay mode of \(H^\pm \rightarrow W^\pm H\) could then be a prominent channel too in the case of \(m_{H^\pm } \gg m_H\).

The phenomenological features of \(H^\pm \) are a subject of some detail, since one could consider either \(m_{H^\pm } < m_t\) or \(m_{H^\pm } > m_t\). Due to this fact, the decay modes for our studies are largely dependent on \(m_{H^\pm }\), following the appropriate mixing parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \). We explicitly consider the case in which \(m_{H^\pm } > m_t\). The production of \(H^\pm \) at the LHC would then follow two production mechanisms which can have sizeable production cross sections. These are:

-

\(2 \rightarrow 2\), \(p p \rightarrow gb(g\bar{b}) \rightarrow tH^- (\bar{t}H^+)\), and

-

\(2 \rightarrow 3\), \(p p \rightarrow gg/qq^\prime \rightarrow t H^- \bar{b} + \bar{t} H^+ b\).

Additionally, \(H^\pm \) production at hadron colliders can be studied through Drell–Yan like processes for pair production (i.e. \(qq \rightarrow H^+H^-\)). Similarly, the associated production with W bosons (\(qq \rightarrow H^\pm W^\pm \)), and pair production through ggF can also be studied.

The prominent decay modes for \(H^\pm \) are \(H^\pm \rightarrow tb\), \(H^\pm \rightarrow \tau \nu \) and \(H^\pm \rightarrow W^\pm h\). With the allowed vertices in the 2HDM, one could think of channels where \(H^\pm \) couples with H (and thereafter \(H \rightarrow h \chi \chi \)). This allows us to study a final state in terms of \(\chi \). Therefore, the decay mode \(H^\pm \rightarrow W^\pm H\) can be highlighted in these studies as a prominent channel. The phenomenology of \(H^\pm \) also depends on whether (i) \(m_h< m_H < m_A\) or (ii) \(m_h< m_A < m_H\), since \(m_{H^{\pm }}\) could be considered as heavy as \(m_A\).

4.4 The additional scalars S and \(\chi \)

The inclusion of S and \(\chi \) in the model is especially significant in terms its phenomenology, since the signatures arising from the 2HDM scalars have mostly been addressed in other work already. With this in mind, the combination of the 2HDM with \(\chi \) and S can lead to many interesting final states useful for study – lists of these can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

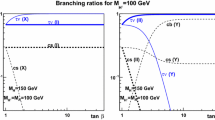

The dominant production mechanism of S is assumed to be through the decay processes \(H\rightarrow SS\) and \(H\rightarrow Sh\). The admixture of these decays is controlled by a ratio of BRs, defined by \(a_1\equiv { \text {BR}(H\rightarrow SS) \over \text {BR}(H\rightarrow Sh)}\). S is assumed to be similar to the SM Higgs boson, in the sense that its couplings to SM particles have the same structure as h. These couplings are then dependent on \(m_S\), and a choice of \(m_S\) therefore has implications on the final states that can be studied. Within the mass range considered (i.e. between \(m_h\) and \(m_H - m_h\)), S can be in one of two regions. The first is dominated by \(S\rightarrow VV\), when \(m_S\gtrsim 2m_W\sim 160\) GeV. The second is when \(m_S\lesssim 2m_W\), and in this region S has non-negligible BRs to various decay products such as \(b\bar{b}\), VV, gg, \(\gamma \gamma \), \(Z\gamma \) etc.

In this model, S is also assumed to be a portal to DM interactions through the decay mode \(S\rightarrow \chi \chi \). With all other couplings to SM particles fixed, the BR to \(\chi \chi \) is a free parameter in the theory. When adding this decay mode, all of the SM decay modes are scaled down by \(1-\text {BR}(S\rightarrow \chi \chi )\), and the total width of S increases accordingly (although in practical studies, a narrow width approximation will suffice).

The SM Higgs boson has stringent experimental limits on its invisible BR. In this model, this is interpreted by the fact that the \(h\rightarrow \chi \chi \) BR is suppressed by the choice of \(m_\chi \sim m_h/2\). Therefore, S is an important component of the model since is useful to study events which can have an arbitrarily large amount of \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) depending on \(m_H\), \(m_S\) and \(\text {BR}(S\rightarrow \chi \chi )\).

5 Analysis of selected leptonic signatures

In order to understand the impact that the model has on certain leptonic final states, a series of analyses are presented in this section. For these, we consider the following mass ranges for each new particle:

-

(a)

Light Higgs: \(m_h = 125\) GeV (assumed as the SM Higgs).

-

(b)

Heavy Higgs: \(2 m_h< m_H < 2 m_t\).

-

(c)

CP-odd Higgs: \(m_A > (m_H + m_Z)\).

-

(d)

Charged Higgs: \((m_H + m_W)< m_{H^\pm } < m_A\).

-

(e)

Additional scalars: \(m_\chi < m_h/2\) and \(m_h \lesssim m_S \lesssim (m_H - m_h)\).

Based on these mass choices, we can study the BRs of 2HDM scalars into the SM particles and the additional scalars \(\chi \) and S as listed in Table 1 with the following production channels:

-

(a)

\(g g \rightarrow h\), H, A, S,

-

(b)

\(p p \rightarrow t H^- (\bar{t} H^+)\), \(t H^-\bar{b} + \bar{t} H^+ b\), \(H^+ H^-\), \(H^\pm W^\pm \).

There are many interesting phenomenological aspects we can consider with the combination of production and decay modes discussed above (the theory pertaining to the dominant production modes of A, H through ggF in a Type-II 2HDM are given in Appendix A and list of several search modes are listed in Table 2). It is not feasible to analyse all of the possible final states that could provide potential for discovery. As a case study, we rather focus on a few striking signatures driven by the production of multiple leptons. These signatures are also dependent on the production of a non-negligible amount of \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\). However, the signatures have been chosen such that the first two (Sects. 5.1 and 5.2) do not rely on the S’s interaction with DM, whereas the third (Sect. 5.3) does. This is an example of how the “simplified model” approach is useful in that different searches can be used to constrain different parameters of the theory.

For Sects. 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3, some plots of key signature distributions are shown and discussed. These plots were made from selecting Monte Carlo (MC) events generated in Pythia 8.219 [29] using custom Rivet [30] routines. In all three cases, 500,000 events were generated and a selection efficiency was determined based on cuts and criteria. These events are not passed through a detector simulation. The reason for this is that our intentions are not to model the profile of \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) with accuracy, but rather provide a signature of the general region in which \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) could be expected, given the parameter constraints.Footnote 5 For the first two analyses, leptons were defined as either electrons or muons with \(p_\text {T}>15\) GeV and \(|\eta |<2.47~(2.7)\) for electrons (muons). A crude lepton isolation is applied by vetoing any leptons which share a partner lepton within a cone of radius \(\Delta R=\sqrt{(\Delta \phi )^2+(\Delta \eta )^2}=0.2\) around it, and any leptons coming from a hadron decay are vetoed.

The mass points considered in these distributions are relatively close to the central points in the ranges we are considering here. The mass of S is fixed to 150 GeV, where it still enjoys a wide range of decay modes due to its SM-like nature – at this mass the BRs to \(b\bar{b}\) and VV are both non-negligible allowing for sensitivity in di-jet and di-boson searches, while a lighter S runs the risk of being too close to the Higgs mass for a comfortable experimental resolution. The mass of H is considered at the two values 275 GeV and 300 GeV. A mass close to 275 GeV does have some motivation from Ref. [16] but is also interesting since the \(H\rightarrow SS\) decay is then off-shell. The on-shell behaviour is probed by also selecting the point \(m_H=300\) GeV, and \(a_1\) is used is chosen such that \(\text {BR}(H\rightarrow SS)=\text {BR}(H\rightarrow Sh)=0.5\) in order for both decay mechanisms to be explored evenly. \(\text {BR}(S\rightarrow \chi \chi )\) is chosen to be 0.5 to probe intermediate \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) production mechanisms.

5.1 \(H\rightarrow 4W\rightarrow 4l+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \)

Various leptonic kinematic distributions (normalised to unity) pertaining to the process \(H\rightarrow 4W\rightarrow 4l+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \), as described in Sect. 5.1

Assuming a large enough cross section for the single production of H, the decays \(H\rightarrow SS, Sh\) can lead to a sizeable production of 4 Ws. The leptonic decays would produce 4 charged leptons (\(e, \mu \)) in conjunction with large \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\). Due to the spin-0 nature of the S, h bosons the leptons of the decay of each boson appear close together [32], leading to an even more striking signature.

Figure 4 displays the kinematics of the leptons for \(m_H=275, 300\,\)GeV and \(m_S=150\,\)GeV for a proton–proton centre of mass energy of 13 TeV. Results are shown assuming \(a_1=1\) and \(\text {BR}(S\rightarrow \chi \chi )=0.5\). In the event generation, both S and h are forced to decay to WW, and these Ws are forced to decay semi-leptonically (including \(\tau \nu _\tau \) decays, since these can result in final states containing muons or electrons). Given the \(gg\rightarrow H\) cross section range mentioned in Sect. 4.1, one could expect a cross section times BR of as much as about 50 fb for this process at the mass points considered here.

The upper left plot shows the invariant mass of the 4-lepton system (\(m_{4l}\)). In the mass range of interest here the background is suppressed and it is dominated by the non-resonant production of di-Z bosons in which at least one is off-shell [33, 34]. The production of the SM Higgs boson would need to be taken into account as a background. The contribution from processes where at least one lepton arises from hadronic decays is sub-leading to the production of \(pp\rightarrow ZZ^*\rightarrow 4l\).

The upper right plot displays a distribution of the smallest \(\Delta R\) between opposite-sign leptons. This variable exploits the spin-0 nature of the S, h bosons.Footnote 6 The distribution suffers from a cut-off due to the requirement that leptons be apart from each other by \(\Delta R> 0.4\) due to isolation requirements. The left plot in the middle displays the sum of the di-lepton azimuthal angle separation for the two opposite-sign pairs (\(\Delta \phi _{+-}\)). Here the choice of lepton pairs is performed so as to minimise the sum of the di-lepton azimuthal angle separation. The corresponding sum of \(\Delta R\) distances for this choice of lepton pairing is shown in the middle right plot. The lower plot displays the transverse momentum of the 4-lepton system and the \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\). These distributions are significantly different from what one would expect from the residual backgrounds from \(pp\rightarrow ZZ^*\rightarrow 4l\).

The production of \(t\overline{t}Z\) is a source of four charged leptons [35]. This background can be suppressed by a combination of requirements including vetoing on the presence of jets and b-jets. The production 4Ws in the standard model is dominated by \(t\overline{t}t\overline{t}\) [36, 37] and \(t\overline{t}WW\) [37] are significantly smaller and can be neglected. The production of \(t\overline{t}t\overline{t}\) with other final states has been investigated and no significant excess in the data has been observed with respect to the SM prediction [38].

Various hadronic and leptonic kinematic distributions (normalised to unity) pertaining to the process \(t\overline{t}H\rightarrow 6W\rightarrow l^{\pm }l^{\pm }l^{\pm }+X\), as described in Sect. 5.2

5.2 \(t(t)H\rightarrow 6W\rightarrow l^{\pm }l^{\pm }l^{\pm }+X\)

The production of double and single top quarks in association with the heavy scalar produce up to 6 Ws in association with b-quarks. This leads to the possibility of producing three same-sign isolated charged leptons (\(l^{\pm }l^{\pm }l^{\pm }\)), a unique signature at hadron colliders. The production of same-sign tri-leptons, including non-isolated leptons from heavy quark decays was, suggested in Ref. [39] to tag top events. The production of isolated same-sign tri-leptons has been studied in the context of the search for new leptons [40] and in R-parity violating SUSY scenarios [41, 42]. Background studies performed in Refs. [40, 42] indicate that the production of three same-sign isolated leptons is very small, less than \(1\times 10^{-2}\,\)fb for a proton–proton centre of mass of 13 TeV. The background would be dominated by the production of \(t\overline{t}W\) with additional leptons from heavy flavour decays. This background is reducible by means of isolation, impact parameters and other requirements [33, 34]. With a reasonable choice of parameters a fiducial cross section of 0.5 fb can be predicted for 13 TeV centre of mass energy, rendering the search effectively background free.

It is relevant to study the kinematics of the final state here, as detailed in Fig. 5. The event generation allowed for the decay of S and h into any channels involving a W, Z or \(\tau \). To ensure a clean signal, leptons were only selected if they did not come from a hadron decay – these processes contain many B-hadrons which can decay into leptons. Under these conditions, the efficiency in selected at least 3 leptons in an event was about 8 %. Of these events, about 15 % would contain a group of three same-sign leptons. The upper left and right plots display tri-lepton invariant mass and the scalar sum of the transverse momenta (\(H_\text {T}\)) of the leptons, respectively. The transverse momentum of the three leptons is shown in the middle left plot. The \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) distribution is shown in the middle right plot. The average \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) in these evens is significant and it adds to the uniqueness of the signature.

Since the production of three same-sign isolated leptons requires the presence of at least six weak bosons and/or \(\tau \) leptons, a large number of jets is expected from those particles that do not decay leptonically. This makes the production of three same-sign isolated leptons even more striking. Hadronic jets are defined using the anti-\(k_T\) algorithm [43] with the parameter \(R=0.4\). Jets are required to have transverse momentum \(p_\text {T}>25\,\)GeV and to be in the range \(|\eta |<2.5\). The jet multiplicity of jets is shown in the lower left plot. The distribution peaks around 4–5 with a long tail stretching to 8 or more jets. The differences displayed by changing \(m_H\) are due to the fact that in the case of \(m_H=275\) GeV one of the S bosons in \(H\rightarrow SS\) becomes off-shell, reducing the transverse momentum of the jets. The \(H_\text {T}\) constructed with jets is shown in the lower right plot.

It is worth noting that the distributions shown in Fig. 5 also apply to the combination of three leptons where the total charge is \({\pm } 1\). There the SM backgrounds are significant, although the signal rate is about 6 times larger.

The production of H with single top is not suppressed with respect to the \(t\overline{t}\) production, as it is in the production of the SM Higgs boson. The kinematic distributions shown in Fig. 5 are similar to those displayed by the tH production with the exception of the net multiplicity and the jet \(H_\text {T}\), due to the reduced production of b-jets. Similar discussion applies to the production of \(H^{\pm }\rightarrow W^{\pm }H\).

5.3 \(A\rightarrow ZH\rightarrow Z+\text {jets}+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \)

If we consider Eq. B.7, we note that in the limit where \(\cos (\beta -\alpha )\rightarrow 0\) (and therefore \(\sin (\beta -\alpha )\rightarrow 1\)), the coupling strength in A–Z–H becomes large – this limit applies in the case where H is SM-like. For this reason, a prime search channel for A lies in the \(A\rightarrow ZH\) decay, if \(m_A\) is large enough. If \(H\rightarrow SS,~Sh\), then there are two obvious LHC-based searches which could already shed light on this decay mode. These are the typical SUSY \(Z+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \) [44–46] and the Zh (where \(h\rightarrow b\bar{b},~\tau \tau \)) searches [47–49].

Using the model presented in this paper, a Rivet analysis was designed to mimic the ATLAS Run 2 \(Z+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \) selection, and events were passed through this selection after being generated and showered at 13 TeV. The process which was generated is \(gg\rightarrow A\rightarrow ZH\), and thereafter \(Z\rightarrow \ell \ell \) (where \(\ell =e,\mu \)) and \(H\rightarrow SS,Sh\). Both S and h are left open to decay, with S at 150 GeV and having SM-like BRs as well as \(BR(S\rightarrow \chi \chi )=0.5\). With \(a_1=1\), the admixture of SS and Sh is considered to be equal. \(m_H\) was considered at 300 GeV, \(m_\chi =60\) GeV and \(m_A\) took on the values 600 and 800 GeV. With this choice of parameters, the process described here is well within current limits for monojet and \(b\bar{b}+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \) searches at the LHC, as discussed in Table 3.

Kinematic distributions of the leptons in \(A\rightarrow ZH\), where \(H\rightarrow SS,~Sh\). The top four pertain to the ATLAS Run 2 \(Z+E_\text {T}^\text {miss} \) SR-Z selection, where the \(\mu \mu \) properties are studied since its efficiency is slightly higher than that of ee. The bottom two figures pertain to the ATLAS Run 2 \(A\rightarrow Zh~(h\rightarrow b\bar{b})\) selection, with the 1 b-tag category on the left and the 2 b-tag category on the right

The results of this are shown in the first four plots in Fig. 6. Comparing with the distributions in Ref. [44], the shapes of the distributions seem consistent with the data. The \(p_\text {T}\) of the di-lepton system is sensitive to the mass of A, and can be used as a discriminant for its search. The selection efficiencies for the \(m_A=600\) and 800 GeV simulations are 0.68 and 1.86 % respectively. The ATLAS Run 2 excess of \({\sim }11\) events at \(L=3.2\,\text {fb}^{-1}\) can therefore be explained by a \(gg\rightarrow A\rightarrow ZH\) production cross section in the order of tens of picobarns. However, contributions from \(pp\rightarrow H\rightarrow SS,Sh\) production could also be a factor to account for, and in this case there would not only be contributions to the Z peak region (i.e. where \(m_{\ell \ell }\sim m_Z\)), but also in the regions where \(m_{\ell \ell }\) is significantly smaller or larger than \(m_Z\). This is due to the fact that in \(H\rightarrow SS,Sh\), S can have a large BR to WW, and di-lepton pairs will come with \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) in the form of neutrinos for this decay, whereas jets could be found in the decay of the other S or h.

The same events were passed through a selection mimicking the ATLAS Run 2 \(A\rightarrow Zh\) (where \(h\rightarrow b\bar{b}\)) search [48]. While there has so far been no significant excess in this channel, it is interesting to understand how the kinematics look for \(A\rightarrow ZH\). The discriminant of these searches is typically the mass of the vector boson and Higgs boson pair, as reconstructed through a di-lepton and \(b\bar{b}\) system in the 2 lepton category (for the 0 lepton category, a transverse mass is calculated instead). The mass of the Zh system is shown by the last two plots in Fig. 6. On the right is the 1 b-tag category and on the left is the 2 b-tag category. Both plots are shown in the categories with low \(p_\text {T}\) of the Z (the high \(p_\text {T}\) categories have a small selection efficiency). The selection efficiency is dominant in the 2 b-tag category with 2.2 and 1.8 % for \(m_A=600\) and 800 GeV, respectively. The mass distributions do not peak at \(m_A\) because the final state is not just \(\ell \ell b\bar{b}\) – more particles can come from the decay of \(H\rightarrow SS,~Sh\), making the final state more diverse. Note that there is also a mass dependence on the b-tag categorisation. This is due to the fact that the \(b\bar{b}\) system four vector is scaled to the Higgs mass in the analysis, whereas in this case \(S\rightarrow b\bar{b}\) could also occur, distorting the kinematics.

6 Summary

In this work we have presented the theory and rationale for introducing a number of new scalars to the SM. The particle content of the proposed model comes from a Type-II 2HDM and two new scalars, S and \(\chi \).

The study follows previous work (in Ref. [16]), which used H and \(\chi \) to predict a distorted Higgs boson \(p_\text {T}\) spectrum through the effective decay \(H\rightarrow h\chi \chi \). In this work, the effective interaction is assumed to be mediated by the scalar S, and H is taken to be the heavy CP-even component of a Type-II 2HDM. The theoretical aspects of the equivalence between the effective model and the model presented in this paper is described in detail throughout Sects. 2 and 3.

With these new scalars, it is clear that a great deal of interesting phenomenology can be studied. Within certain mass ranges, a variety of signatures of the model have been discussed. S, in particular is a key element in the model, since it acts as a portal to DM interactions through its \(S\rightarrow \chi \chi \) decay mode. It is also SM Higgs-like, and thus can be tagged through various decay modes. By a choice of parameters, it is assumed to be produced dominantly through the decay \(H\rightarrow SS\) and \(H\rightarrow Sh\), and is therefore likely to produce events that come with jets, leptons and \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\).

In addition to the discussion of the model, a few selected leptonic signatures have been explored using MC predictions and event selections. Various interesting distributions have been shown, as well as the rates and efficiencies of some processes which have relatively small SM backgrounds. The selected parameter points have also been compared to existing limits in the data, where applicable, and no violation of these limits has been found.

With the LHC continuing to deliver data at a staggering rate, it is important to keep testing models in the search for new physics. With a model dependence, experimentalists have a much clearer picture of what to look for in the data and how to bin results. It is evident that some hints exist in the search for new scalars at the LHC [16], and therefore the scalar sector is important to probe on both a theoretical and experimental level.

Notes

One can also introduce a complex scalar in theory, the consequence of which alters the choice of symmetry. The \(\mathbb {Z}_2\) symmetry would then be promoted to a global U(1) and its spontaneous breaking would lead to a massless pseudoscalar.

S is a scalar particle with various decay modes, therefore having all possible branchings to other particles. As a result, the symmetry requirements for a gauge invariant set of vertices in the Lagrangian is different.

We make sure the ratio r is positive definite so that there will not be any negative interference due to the choice of negative values of couplings \(\lambda _{_{HSS}}\) or \(\lambda _{_{HhS}}\).

It should be noted that in the effective Lagrangian discussed in Sect. 3, the scalar H need not be a 2HDM heavy scalar.

Having said this, the state of the art fast simulation package Delphes 3’s [31] predictions of detector effects in \(E_\text {T}^\text {miss}\) are reasonable, but still not completely compatible with the full simulation packages used by ATLAS and CMS. Detector simulation could be studied in a future work.

The kinematics of the decay depend on the tensor structure of the SVV coupling.

References

F. Englert, R. Brout, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 321 (1964)

P.W. Higgs, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 508 (1964)

P.W. Higgs, Phys. Lett. 12, 132 (1964)

G.S. Guralnik, C.R. Hagen, T.W.B. Kibble, Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 585 (1964)

ATLAS Collaboration (G. Aad et al.) Phys. Lett. B 716, 1 (2012)

CMS Collaboration (S. Chatrchyan et al.) Phys. Lett. B 716, 30 (2012)

J.E. Gunion, H.E. Haber, G. Kane, S. Dawson, The Higgs Hunter’s Guide (ABP, PERSEUS PUBLISHING, Cambridge, 1990)

G.C. Branco, P.M. Ferreira, L. Lavoura, M.N. Rebelo, M. Sher, J.P. Silva, Phys. Rep. 516, 1 (2012)

S.F. King, J. Phys. G 42, 123001 (2015). doi:10.1088/0954-3899/42/12/123001. arXiv:1510.02091 [hep-ph]

J. Abdallah et al., Phys. Dark Univ. 9–10, 8 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.dark.2015.08.001. arXiv:1506.03116 [hep-ph]

G. Aad et al. [ATLAS Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 115(9), 091801 (2015). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.091801. arXiv:1504.05833 [hep-ex]

ATLAS Collaboration, arXiv:1604.02997 [hep-ex]

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], arXiv:1606.01522 [hep-ex]

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], JHEP 1604, 005 (2016). doi:10.1007/JHEP04(2016)005. arXiv:1512.08377 [hep-ex]

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Eur. Phys. J. C 76(1), 13 (2016). doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3853-3. arXiv:1508.07819 [hep-ex]

S. von Buddenbrock et al., (2015). arXiv:1506.00612 [hep-ph]

M. Kumar et al., Submitted to the book of Proceedings of the High Energy Particle Physics workshop, February 8th–10th 2016, iThemba LABS, South Africa. arXiv:1603.01208 [hep-ph]

CMS Collaboration, CMS PAS HIG-16-007

S. Chatrchyan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Nat. Phys. 10, 557 (2014). doi:10.1038/nphys3005. arXiv:1401.6527 [hep-ex]

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], JHEP 1510, 144 (2015). doi:10.1007/JHEP10(2015)144. arXiv:1504.00936 [hep-ex]

CMS Collaboration, CMS-PAS-HIG-15-001

B. Coleppa, F. Kling, S. Su, JHEP 1412, 148 (2014)

B. Coleppa, F. Kling, S. Su, JHEP 1401, 161 (2014)

B. Coleppa, F. Kling, S. Su, arXiv:1308.6201 [hep-ph]

A. Drozd, B. Grzadkowski, J.F. Gunion, Y. Jiang, JHEP 1411, 105 (2014)

C.Y. Chen, M. Freid, M. Sher, Phys. Rev. D 89(7), 075009 (2014)

G. Aad et al. [ATLAS and CMS Collaborations], JHEP 1608, 045 (2016). doi:10.1007/JHEP08(2016)045. arXiv:1606.02266 [hep-ex]

LHC Higgs Cross Section Working Group, S. Heinemeyer, C. Mariotti, G. Passarino, R. Tanaka (Eds.), Handbook of LHC Higgs Cross Sections: 3. Higgs Properties, CERN-2013-004 (CERN, Geneva, 2013). arXiv:1307.1347 [hep-ph]

T. Sjöstrand et al., Comput. Phys. Commun. 191, 159 (2015)

A. Buckley, J. Butterworth, L. Lonnblad, D. Grellscheid, H. Hoeth, J. Monk, H. Schulz, F. Siegert, Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 2803 (2013)

J. de Favereau et al. [DELPHES 3 Collaboration], JHEP 1402, 057 (2014). doi:10.1007/JHEP02(2014)057. arXiv:1307.6346 [hep-ex]

M. Dittmar, H.K. Dreiner, Phys. Rev. D 55, 167 (1997)

S. Chatrchyan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Phys. Rev. D 89(9), 092007 (2014)

G. Aad et al. [ATLAS Collaboration], Phys. Rev. D 91(1), 012006 (2015)

A. Lazopoulos, T. McElmurry, K. Melnikov, F. Petriello, Phys. Lett. B 666, 62 (2008)

G. Bevilacqua, M. Worek, JHEP 1207, 111 (2012)

J. Alwall et al., JHEP 1407, 079 (2014)

The ATLAS collaboration, Search for four-top-quark production in final states with one charged lepton and multiple jets using 3.2 fb\(^{-1}\) of proton–proton collisions at \(\sqrt{s}\) = 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector at the LHC. ATLAS-CONF-2016-020

V.D. Barger, R.J.N. Phillips, Phys. Rev. D 30, 1890 (1984)

V.E. Ozcan, S. Sultansoy, G. Unel, J. Phys. G 36, 095002 (2009). Erratum: [J. Phys. G 37, 059801 (2010)]

B. Mukhopadhyaya, S. Mukhopadhyay, Phys. Rev. D 82, 031501 (2010)

S. Mukhopadhyay, B. Mukhopadhyaya, Phys. Rev. D 84, 095001 (2011)

M. Cacciari, G.P. Salam, G. Soyez, JHEP 0804, 063 (2008)

The ATLAS collaboration, ATLAS-CONF-2015-082

G. Aad et al. [ATLAS Collaboration], Eur. Phys. J. C 75(7), 318 (2015). Erratum: [Eur. Phys. J. C 75 (2015) no. 10, 463]. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3661-9. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3518-2. arXiv:1503.03290 [hep-ex]

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], JHEP 1504, 124 (2015). doi:10.1007/JHEP04(2015)124. arXiv:1502.06031 [hep-ex]

G. Aad et al. [ATLAS Collaboration], Phys. Lett. B 744, 163 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2015.03.054. arXiv:1502.04478 [hep-ex]

The ATLAS collaboration, ATLAS-CONF-2016-015

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Phys. Lett. B 748, 221 (2015). doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2015.07.010. arXiv:1504.04710 [hep-ex]

V. Khachatryan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Eur. Phys. J. C 75(5), 235 (2015). doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3451-4. arXiv:1408.3583 [hep-ex]

The ATLAS collaboration [ATLAS Collaboration], ATLAS-CONF-2016-086

The ATLAS collaboration [ATLAS Collaboration], ATLAS-CONF-2016-087

Acknowledgments

The work of N.C. and B. Mukhopadhyaya was partially supported by funding available from the Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India for the Regional Centre for Accelerator-based Particle Physics (RECAPP), Harish-Chandra Research Institute. The Claude Leon Foundation are acknowledged for their financial support. The High Energy Physics group of the University of the Witwatersrand is grateful for the support from the Wits Research Office, the National Research Foundation, the National Institute of Theoretical Physics and the Department of Science and Technology through the SA-CERN consortium and other forms of support. T.M. is supported by funding from the Carl Trygger Foundation under contract CTS-14:206 and the Swedish Research Council under contract 621-2011-5107.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Production: \(gg \rightarrow A, H\)

In Type-II 2HDMs, the ggF production cross section of the CP-odd Higgs A is done by a simple rescaling of the SM Higgs (h) cross section [24]:

and is given as

In this expression \(\tau _f = 4 m_f^2/ m_A^2\) and the scalar and pseudoscalar loop factors are given by

where

with \(\eta _{\pm } \equiv 1 \pm \sqrt{1-\tau }\). Here we have ignored the contributions of the other Higgs bosons in the loop, which are typically small. Similarly, the ggF cross section for the CP-even Higgs (through a rescaling of the SM cross section) is given as:

where the loop factors (the Fs) are defined in Eq. A.3.

Appendix B: Interaction Lagrangians in 2HDM

Interactions with electroweak vector bosons V (\(W^\pm , Z\)) and the photon field (\(A_\mu \)) with \(\phi \) and \(H^\pm \) are given as

and

In a Type-II 2HDM framework, the Yukawa terms are as follows:

with \(y_{ut} = \sqrt{2} y_{m_t}/(v \sin \beta )\) and \(y_{ub} = \sqrt{2} y_{m_b}/(v \cos \beta )\). The relevant trilinear scalar interactions are part of the Lagrangian \({\mathscr {L}}_{\phi \phi \phi }\),

where the couplings have the following expressions:

Here \(M^2\) is the shorthand notation for \(m^2_{12}/(\sin \beta \cos \beta )\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

von Buddenbrock, S., Chakrabarty, N., Cornell, A.S. et al. Phenomenological signatures of additional scalar bosons at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 580 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-4435-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-016-4435-8