Abstract

Previous studies have reported low self-esteem contributes to depressive symptoms among adolescents, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear. The present study aimed to examine the mediating roles of hope and anxiety in the relationship between self-esteem and depressive symptoms. 431 adolescents between 13 and 18 years volunteered to complete a battery of questionnaires that included measures on the variables mentioned above. Results found that hope or anxiety mediated the association between self-esteem and female adolescents’ depression, while only anxiety mediated the association between self-esteem and male adolescents’ depression. Our findings highlight different underlying mechanisms between female and male adolescents. In the prevention and intervention of depressive symptoms, sound programs should be selected according to the gender characteristics of adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The National Mental Health Development Report (2019–2020) reports that 24.6% of adolescents in China are diagnosed with depression and 7.4% with severe depression. In recent years, depression has become common in Chinese adolescents. Gijzen et al. (2021) state that adolescents rather than individuals of other ages are more likely to experience some social-emotional disorders, such as depressive symptoms. Existing studies have found that depressive symptoms are related to suicidal behavior (Gijzen et al. 2021; Gili et al. 2019; Islam et al. 2021; Piqueras et al. 2019; Shen and Wang 2023). More studies are needed to examine risk factors associated with adolescent depressive symptoms for early prevention and intervention.

According to Robins and Trzesniewski’s view (2005), adolescence is a turbulent time during which the level of self-esteem of adolescents is dramatically reduced. According to the vulnerability model proposed by Butler et al. (1994), low self-esteem may be a potential risk of adolescent depression. Adolescents with low self-esteem are unable to evaluate their self-worth correctly which in turn contributes to depression (Orth et al. 2012; Rosenberg 1965). The assumption has been demonstrated by a body of cross-sectional studies on adolescents (Fiorilli et al. 2019; Jiang et al. 2021). More importantly, a longitudinal research testifying to the causal relationship between low self-esteem and adolescents’ depression consistently found that low self-esteem contributed to adolescent depression (Zhou et al. 2020). Despite previous studies showing that low self-esteem is a potential risk factor for the occurrence of adolescent depression, whether low self-esteem influences adolescent depression through other possible risk factors remains unclear. Inspired by prior research conducted by Cimino et al. (2015) and Brofenbrennery theory (Ryan 2001), the present study hypothesized that low levels of self-esteem, a typical characteristic of adolescents, and other risk factors work together to influence the development of adolescent depressive symptoms. Recently, vulnerability to depression has attracted much attention from scholars and mainly refers to a series of risk factors contributing to the occurrence of depression. The cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory states a variety of negative cognitive and coping styles can be regarded as cognitive vulnerability to depression which can make individuals suffer from depressive symptoms in certain situations (Hankin and Abramson 2001).

Low hope is a typical cognitive vulnerability to depression. It means that an individual does not have the cognitive belief of successfully achieving goals and the coping capacity to generate sound routes to complete goals (Zhou et al. 2018). It has been documented that hope is closely associated with self-esteem (Donald et al. 2019; Frankham et al. 2020). That is, high self-esteem contributes to the formation of a high sense of hope, on the contrary, low self-esteem will reduce the level of hope. Moreover, adolescents with low hope suffer from more depressive symptoms compared with ones with high hope (Zhang et al. 2019). Accordingly, based on the above studies, the present study proposed a hypothesis that low hope increases the risk of depression among adolescents with low self-esteem. Accept for low hope, anxiety is regared as another potential co-occurring risk factor of depression in adolescents with low level of self-esteem. Many quantitative studies have found that self-esteem shows close and negative association with anxiety among adolescents (Berber Çelik and Odacı 2020; Thoma et al. 2021). Furthermore, anxiety is often accompanied by symptoms of depression. Kwong et al. (2021) found that the polygenic risk for anxiety is associated with an increasing rate of change in adolescent depression. According to these previous studies, the present study proposed the second hypothesis that anxiety contributes to depression among adolescents with low self-esteem.

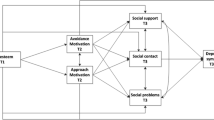

Taken together, despite that the relationship between low levels of self-esteem and depression has been testified among adolescents, the underlying mechanism remains unknown. According to Cimino et al. (2015) viewpoint and Brofenbrennery’s theory (Ryan 2001), the present study examined what risk factors increase depression among adolescents which are characterized by low self-esteem. We hypothesized that low hope and anxiety will increase the risk of depression in adolescents with low self-esteem, showing that hope or anxiety may play a mediation role in the association between self-esteem and adolescent depression. Given that previous studies showed that gender was important predictive factor for adolescent depressive symptoms (Bai et al. 2020; Hards et al. 2020; Osborn et al. 2020; Puukko et al. 2020; Qi et al. 2020; Slavich et al. 2020; Zhai et al. 2020), an exploratory hypothesis was proposed that hope or anxiety may play different roles in the association between self-esteem and depression, separately for male and female adolescents.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Under the approval of the principal of a public middle school, a trained researcher first gathered head teachers together and explained the objective of the online survey to them. Then, head teachers posted the survey link to student groups such as WeChat groups or QQ groups. Given that adolescents have certain literacy ability, each questionnaire instruction was presented in the form of text at the beginning of the questionnaire. Adolescents voluntarily participated in this online survey. Non-participation adolescents were assured that this survey had nothing to do with their grades. Questionnaires were administrated individually. Finally, data were collected from 431 adolescents aged between 13 and 18 years (M = 15.73; SD = 0.89). And 52% were females in this sample. All got compensation for their participation. Before this online survey formally began, written informed consents were provided by adolescents’ guardians.

Measures

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (SES) containing 10 self-report items was used to measure adolescent self-esteem in the present study (Rosenberg 1965). Respondents are asked to rate items on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Total scores were calculated. The higher the score, the higher the self-esteem. Previous studies have shown that the SES has good reliability and validity in Chinese samples (Guo et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020). Cronbach’s α for the SES in the present study was 0.85.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to evaluate adolescent depressive symptoms in the past week (Radloff 1991). The CES-D contains 20 items which are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Total scores were calculated in the present study. Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of depressive symptoms. The CES-D has good metrological attributes such as reliability and validity in previous research on Chinese samples (Chi et al. 2019; Gong et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020; Q. Zhou et al. 2018). Cronbach’s α for the CES-D in the present study was 0.91.

The Children’s Hope Scale (CHS) is widely used to estimate adolescents’ hopeful thinking containing 6 self-report items. Each item is scored according to a 6-point scale ranging from 1 = none of the time to 6 = all of the time. Total scores ranging from 6 to 36 were calculated in the present study. Higher scores present more hopeful thinking. The CHS had good internal consistency among adolescents with Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.86 in the present study.

The present study used 20-item Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS; (Zung 1971)), to measure adolescents’ anxiety. The scale has good psychometric attributes such as reliability and validity in Chinese samples (Li et al. 2019). Respondents rated items on a 4-point response scale ranging from 1 = a little of the time to 4 = most of the time according to their situation. Total scores for each respondent were created in the present study. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety. The SAS has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.67) in the present study.

Statistical analysis

We first conducted correlation analysis in order to examine the relationship between gender, age, self-esteem, hope, anxiety, and depression. Next, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine different mediation roles of hope and anxiety in the association between self-esteem and depression, separately for male and female adolescents. The constructed model via Mplus V8.3 was tested for fit and was corrected according to the correction index. Based on previous studies (Butler et al. 1994; Hu and Bentler 1999; Kline and Santor 1999), there was a good fit between the constructed models in the present study and empirical data (the constructed model in female adolescents: χ2 = 324.807, df = 6, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.000, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.012, SRMR = 0.008; the constructed model in male adolescents: χ2 = 306.754, df = 6, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.000; CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.019; SRMR = 0.002). The bootstrap method with 5000 resamples was used to examine the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in which if the CIs excluded zero, the mediation effects of hope and anxiety were significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Correlation among the studied variables

As shown in Table 1, the results of correlation analysis showed that gender was closely associated with self-esteem, hope, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (r self-esteem = 0.12, p < 0.05; r hope = 0.17, p < 0.01; r anxiety = −0.10, p < 0.05; r depressive symptoms = −0.11, p < 0.05). Age was closely associated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.12, p < 0.05). Self-esteem was significantly and positively related to hope (r = 0.69, p < 0.001) while self-esteem was significantly and negatively correlated with depressive symptoms and anxiety (r depressive symptoms = −0.64, p < 0.001; r anxiety = −0.33, p < 0.001). Moreover, hope was significantly and negatively linked to depressive symptoms (r = −0.50, p < 0.001). Anxiety was significantly positively related to depressive symptoms (r = 0.49, p < 0.001).

Mediating roles of hope and anxiety in the association between self-esteem and adolescent depressive symptoms.

Mediating roles of hope and anxiety in female adolescents

As illustrated in Table 2, self-esteem significantly and positively predicted hope (β = 1.56, p < 0.001) while self-esteem significantly and negatively predicted anxiety (β = −0.24, p < 0.001). Furthermore, hope had a significant negative effect on depressive symptoms (β = −0.10, p < 0.01) and anxiety had a significant positive effect on depressive symptoms (β = 0.59, p < 0.001). More importantly, the present study found self-esteem still significantly predicted depressive symptoms when hope and anxiety simultaneously entered the constructed multiple mediation model.

The significance of the indirect effects of hope and anxiety was further examined via the bootstrapping method. Table 3 presents 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of total effect, indirect effects of hope and anxiety, and total indirect effect. The indirect effects of hope and anxiety on the relationship between self-esteem and female adolescents’ depressive symptoms were −0.16 and −0.14, accounting for 25.00 and 21.88% of the total effect, respectively. The total indirect effect was −0.30, accounting for 46.88% of the total effect.

Mediating roles of hope and anxiety in male adolescents

As can be seen in Table 4, self-esteem significantly predicted male adolescents’ hope (β = 1.15, p < 0.001) while self-esteem significantly predicted male adolescents’ anxiety (β = −0.15, p < 0.01). Anxiety significantly predicted male adolescents’ depressive symptoms (β = 0.48, p < 0.001) while hope failed to predict male adolescents’ depressive symptoms (β = −0.04, p > 0.05). The present study also found that self-esteem still significantly predicted male adolescents’ depressive symptoms while anxiety rather than hope entered the constructed model.

The significance of the indirect effect of anxiety on the relationship between self-esteem and male adolescents’ depressive symptoms was investigated through the bootstrapping method. Table 5 illustrates 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of total effect and indirect effect of anxiety. The indirect effect of anxiety on the relationship between self-esteem and male adolescents’ depressive symptoms was −0.07, accounting for 11.48% total effect.

Discussion

Our study examined inner mechanisms underlying the association between self-esteem and adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Results showed hope or anxiety partially mediated the negative influence of self-esteem on female adolescents’ depressive symptoms, respectively while anxiety rather than hope played a mediating role in the relationship between self-esteem and male adolescents’ depression. Our study not only highlights the role of self-esteem in adolescents’ depressive symptoms but also reveals different inner mechanisms underlying self-esteem to depression among adolescents of different genders.

Corresponding with previous research, we found that self-esteem significantly predicted adolescent depression. Our result provides evidence for the vulnerability model proposed by Sowislo and Orth (2013) which states low self-esteem contributes to depressive symptoms. Moreover, we also found that female adolescents versus male adolescents suffered from more depression. The result follows previous literature on adolescents demonstrating gender differences (Lewis et al. 2020; Lima et al. 2020; Puukko et al. 2020; Slavich et al. 2020; Thorisdottir et al. 2021; Turney 2021).

According to the above findings and previous studies, SEM was used to investigate the different roles of hope and anxiety in the relationship between self-esteem and depression in male and female adolescents, separately. The results confirm our suspicion that low self-esteem has a negative influence on depression in male and female adolescents through different intrinsic mechanisms. Specifically, female adolescents with high self-esteem reduced depression via an increase in hope or a decrease in anxiety. However, male adolescents with high self-esteem decreased depression via a decrease in anxiety. The findings indicate that male adolescents are not good at mobilizing internal psychological resources (i.e., hope) to cope with depression.

In addition, we also found that self-esteem affected female adolescents’ depression mainly via hope rather than anxiety, while self-esteem affected male adolescents’ depression via anxiety. These results to some extent have some implications for the precise prevention and intervention of depression among different adolescent populations. Specifically, intervention programs aiming to improving psychological cognitive resilience may be more effective in decreasing the occurrence of depression among female adolescents with low self-esteem. However, intervention programs focusing on decreasing negative emotions (i.e., anxiety) may be more effective in decreasing the risk of depression among male adolescents with low self-esteem to decrease the risk of depression. This inference highlights that mental health educators can set up some special courses according to the developmental characteristics of adolescents of different genders to reduce depression among susceptible adolescents, such as ones with low self-esteem.

Taken together, our results reveal inner mechanisms underlying the relationship between self-esteem and adolescent depression. Specifically, low self-esteem increases the risk of female adolescents’ depression via a decrease in hope or an increase in anxiety. However, low self-esteem contributes to male adolescents’ depression via an increase in anxiety. The present study has some limitations that should be considered. First, given that the cross-sectional design is characterized by the inability to infer causality, more longitudinal studies are needed to replicate the roles of hope and anxiety in the association between self-esteem and adolescent depressive symptoms. Second, the present study recruited adolescents from a public middle school by convenience sampling method. The findings should therefore be generalized with caution. Third, hope and anxiety are regarded as mediators in our study. But it remains unclear if other variables moderate the mediating effects of hope and anxiety on the relationship between self-esteem and adolescent depression.

Data availability

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the supplementary files.

References

Bai Q, Lei L, Hsueh F-H, Yu X, Hu H, Wang X, Wang P (2020) Parent-adolescent congruence in phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: A moderated polynomial regression with response surface analyses. J Affect Disord 275:127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.156

Berber Çelik Ç, Odacı H (2020) Does child abuse have an impact on self-esteem, depression, anxiety and stress conditions of individuals? Int J Soc Psychiatry 66(2):171–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019894618

Butler AC, Hokanson JE, Flynn HA (1994) A comparison of self-esteem lability and low trait self-esteem as vulnerability factors for depression. J Personal Soc Psychol 66(1):166–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.166

Chi X, Liu X, Guo T, Wu M, Chen X (2019) Internet addiction and depression in chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Front Psychiatry 10:816. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00816

Cimino S, Cerniglia L, Paciello M (2015) Mothers with depression, anxiety or eating disorders: Outcomes on their children and the role of paternal psychological profiles. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 46(2):228–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0462-6

Donald JN, Ciarrochi J, Parker PD, Sahdra BK (2019) Compulsive internet use and the development of self‐esteem and hope: A four‐year longitudinal study. J Personal 87(5):981–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12450

Fiorilli C, Grimaldi Capitello T, Barni D, Buonomo I, Gentile S (2019) Predicting adolescent depression: The interrelated roles of self-esteem and interpersonal stressors. Front Psychol 10:565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00565

Frankham C, Richardson T, Maguire N (2020) Do locus of control, self-esteem, hope and shame mediate the relationship between financial hardship and mental health? Community Ment Health J 56(3):404–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00467-9

Gijzen MW, Rasing SP, Creemers DH, Smit F, Engels RC, De Beurs D (2021) Suicide ideation as a symptom of adolescent depression. A network analysis. J Affect Disord 278:68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.029

Gili M, Castellví P, Vives M, de la Torre-Luque A, Almenara J, Blasco MJ, Cebrià AI, Gabilondo A, Pérez-Ara MA, Miranda-Mendizabal A (2019) Mental disorders as risk factors for suicidal behavior in young people: A meta-analysis and systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord 245:152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.10.115

Gong Y, Shi J, Ding H, Zhang M, Kang C, Wang K, Yu Y, Wei J, Wang S, Shao N (2020) Personality traits and depressive symptoms: The moderating and mediating effects of resilience in Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord 265:611–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.102

Guo L, Tian L, Huebner ES (2018) Family dysfunction and anxiety in adolescents: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and perceived school stress. J Sch Psychol 69:16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.04.002

Hankin BL, Abramson LY (2001) Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory. Psychological Bull 127(6):773–796. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773

Hards E, Ellis J, Fisk J, Reynolds S (2020) Negative view of the self and symptoms of depression in adolescents. J Affect Disord 262:143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.012

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Islam M, Tasnim R, Sujan M, Hossain S, Ferdous M, Sikder M, Masud JHB, Kundu S, Tahsin P, Mosaddek ASM (2021) Depressive symptoms associated with COVID-19 preventive practice measures, daily activities in home quarantine and suicidal behaviors: Findings from a large-scale online survey in Bangladesh. BMC Psychiatry 21(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03246-7

Jiang S, Ren Q, Jiang C, Wang L (2021) Academic stress and depression of Chinese adolescents in junior high schools: Moderated mediation model of school burnout and self-esteem. J Affect Disord 295:384–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.085

Kline RB, Santor DA (1999) Principles & practice of structural equation modelling. Can Psychol 40(4):381

Kwong AS, Morris TT, Pearson RM, Timpson NJ, Rice F, Stergiakouli E, Tilling K (2021) Polygenic risk for depression, anxiety and neuroticism are associated with the severity and rate of change in depressive symptoms across adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 62(12):1462–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13422

Lewis AJ, Sae-Koew JH, Toumbourou JW, Rowland B (2020) Gender differences in trajectories of depressive symptoms across childhood and adolescence: A multi-group growth mixture model. J Affect Disord 260:463–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.027

Li G, Hou G, Yang D, Jian H, Wang W (2019) Relationship between anxiety, depression, sex, obesity, and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: A short-term longitudinal study. Addictive Behav 90:421–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.12.009

Lima RA, de Barros MVG, Dos Santos MAM, Machado L, Bezerra J, Soares FC (2020) The synergic relationship between social anxiety, depressive symptoms, poor sleep quality and body fatness in adolescents. J Affect Disord 260:200–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.074

Orth U, Robins RW, Widaman KF (2012) Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. J Personal Soc Psychol 102(6):1271–1288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025558

Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Wasil AR, Schleider JL, Weisz JR (2020) Depression and anxiety symptoms, social support, and demographic factors among Kenyan high school students. J Child Fam Stud 29:1432–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01646-8

Piqueras JA, Soto-Sanz V, Rodríguez-Marín J, García-Oliva C (2019) What is the role of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescent suicide behaviors? Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(14):2511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142511

Puukko K, Hietajärvi L, Maksniemi E, Alho K, Salmela-Aro K (2020) Social media use and depressive symptoms—A longitudinal study from early to late adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(16):5921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165921

Qi M, Zhou S-J, Guo Z-C, Zhang L-G, Min H-J, Li X-M, Chen J-X (2020) The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Adolesc Health 67(4):514–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001

Radloff LS (1991) The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolescence 20(2):149–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537606

Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH (2005) Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Curr Directions Psychological Sci 14(3):158–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00353.x

Rosenberg M (1965) Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance Commit Ther Measures package 61(52):18

Ryan DPJ (2001) Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. Retrieved Jan 9:2012

Shen X, Wang J (2023) More than the aggregation of its components: Unveiling the associations between anxiety, depression, and suicidal behavior in adolescents from a network perspective. J Affect Disord 326:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.081

Slavich GM, Giletta M, Helms SW, Hastings PD, Rudolph KD, Nock MK, Prinstein MJ (2020) Interpersonal life stress, inflammation, and depression in adolescence: Testing social signal transduction theory of depression. Depression anxiety 37(2):179–193. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22987

Sowislo JF, Orth U (2013) Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bull 139(1):213–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22987

Thoma MV, Bernays F, Eising CM, Maercker A, Rohner SL (2021) Child maltreatment, lifetime trauma, and mental health in Swiss older survivors of enforced child welfare practices: Investigating the mediating role of self-esteem and self-compassion. Child Abus Negl 113:104925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104925

Thorisdottir IE, Asgeirsdottir BB, Kristjansson AL, Valdimarsdottir HB, Tolgyes EMJ, Sigfusson J, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID, Halldorsdottir T (2021) Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: A longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 8(8):663–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00156-5

Turney K (2021) Depressive symptoms among adolescents exposed to personal and vicarious police contact. Soc Ment Health 11(2):113–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869320923095

Wang X, Gao L, Yang J, Zhao F, Wang P (2020) Parental phubbing and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Self-esteem and perceived social support as moderators. J Youth Adolescence 49(2):427–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01185-x

Zhai B, Li D, Li X, Liu Y, Zhang J, Sun W, Wang Y (2020) Perceived school climate and problematic internet use among adolescents: Mediating roles of school belonging and depressive symptoms. Addictive Behav 110:106501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106501

Zhang H, Chi P, Long H, Ren X (2019) Bullying victimization and depression among left-behind children in rural China: Roles of self-compassion and hope. Child Abus Negl 96:104072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104072

Zhou J, Li X, Tian L, Huebner ES (2020) Longitudinal association between low self‐esteem and depression in early adolescents: The role of rejection sensitivity and loneliness. Psychol Psychotherapy 93(1):54–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12207

Zhou Q, Fan L, Yin Z (2018) Association between family socioeconomic status and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: Evidence from a national household survey. Psychiatry Res 259:81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.072

Zhou X, Wu X, Zhen R (2018) Self-esteem and hope mediate the relations between social support and post-traumatic stress disorder and growth in adolescents following the Ya’an earthquake. Anxiety Stress Coping 31(1):32–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1374376

Zung WW (1971) A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12(6):371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0

Acknowledgements

The National Social Science Fund of China (grant number 19BSH111) and the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (grant number 212102310985) supported our study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design. Data collection and analysis were performed by Jingyi Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Panpan Zhang and Jingyi Li. The final draft of the manuscript was read and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior (No. 202109306).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants’ legal guardians. Data were recorded and numbered in Arabic numerals, which did not include participants’ names.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, H., Zhang, P. & Li, J. The effect of self-esteem on depressive symptoms among adolescents: the mediating roles of hope and anxiety. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 932 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03249-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03249-1

- Springer Nature Limited