Abstract

Based on conservation of resources theory and the work–home resources model, this study examines how and when narcissistic leadership influences employees’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. A total of 363 employees from 61 teams across numerous enterprises based in central China were surveyed using a questionnaire. The study hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling and Monte Carlo simulation analysis. The findings revealed that narcissistic leadership results in the development of a negative team climate, termed “team chaxu climate,” which, in turn, hinders employees’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Furthermore, this study explored the moderating role of leaders’ family affective support in the relationship between narcissistic leadership and team chaxu climate. This study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employee organizational citizenship behavior and empirically validates the work–home resources model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent studies have reported that narcissistic leaders are becoming increasingly common worldwide; the media have characterized prominent business leaders—such as Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, and Jack Welch—as narcissists (Visser et al. 2017). Incumbent leaders have the authority to allocate organizational resources and a strong sense of superiority when dealing with subordinates (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001b; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). Meanwhile, narcissists—typically self-assured, expressive, and inclined to exaggerate their strengths—tend to receive higher leadership ratings and are more likely to distinguish themselves and become leaders than non-narcissists (Brunell et al. 2008; Gauglitz et al. 2023). However, narcissists are extremely egocentric and arrogant, frequently acting for personal benefit, insensitive to others’ needs and recommendations, and challenging to form a healthy connection with (Hogan et al. 1990; Paulhus 1998). Narcissistic leadership generally precipitates unfavorable organizational outcomes (Ouimet 2010; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006), particularly by weakening employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). For example, Li and Zhang (2018) found that narcissistic leadership behaviors elevate employee hindrance stress and negatively impact employees’ OCB. Ha et al. (2020) demonstrated that narcissistic leaders disrupt the principle of reciprocity between leaders and employees, thereby suppressing employees’ OCB. Similarly, Wang et al. (2021) reported that narcissistic leaders undermine employees’ psychological safety and affective organizational commitment, thus decreasing the latter’s OCB. By contrast, some studies have found that narcissistic leaders also promote employees’ OCB. Narcissistic leaders enhance employees’ OCB by providing them with greater autonomy (Zhang et al. 2017) and encouraging them to freely express their opinions regarding current organizational issues (Zhang et al. 2022). Additionally, Zhu et al. (2023) found that subordinates engage in OCB because they admire narcissistic leaders. These divergent findings indicate that the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employee OCB is complex and that our understanding of narcissistic leadership is limited and requires further in-depth research. Specifically, recent research has reported that narcissistic leaders engage in behaviors that deviate from their narcissistic traits—such as developing satisfactory relationships with subordinates and involving them in significant decision-making (Carnevale et al. 2018; Owens et al. 2015). This finding is inconsistent with the previous one that narcissistic leaders cannot develop satisfactory relationships with their subordinates (de Vries and Miller 1985; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). Notably, narcissistic leaders—instead of developing satisfactory relationships with all team members—befriend only some members and alienate others (Huang et al. 2020). However, why narcissistic leaders engage in such behaviors remains unclear.

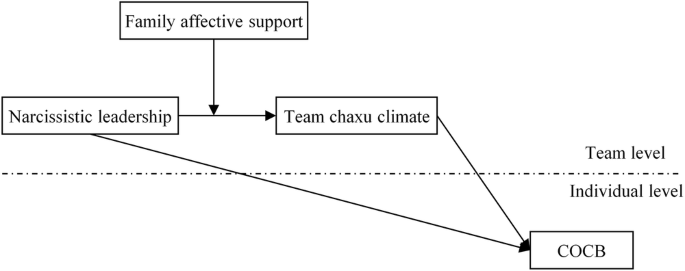

To ascertain why narcissistic leaders exhibit this deviant behavior and how and when narcissistic leadership influences employees’ OCB, we constructed a moderated mediation model based on conservation of resources (COR) theory and the Work–Home Resources (W–HR) model. We argue that narcissistic leadership hinders employees’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior (COCB) by increasing team chaxu climate—a phenomenon whereby team leaders maintain close connections with a minority of members and simultaneously distance themselves from the majority (Liu et al. 2009). This reflects the varying degrees of relationship closeness formed among team members with the controller of team resources (generally, the team leader; Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019). In Chinese enterprises, a clique culture frequently prevails, wherein leaders categorize employees into different circles—such as “inner circles” and “outer circles”—based on attitudes, relationship proximity, and capabilities (Chen and Dian 2018). Consequently, team chaxu climate is frequently observed within teams in Chinese enterprises. Typically, employees having a stronger—compared with those having a weaker—relationship with the resource controller receive more job-related resources (e.g., trust, support, and empowerment; Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019). According to COR theory, individuals are incentivized to conserve existing resources and acquire additional resources to prevent the risk of prospective resource loss (Hobfoll, 1989). We argue that narcissistic leaders exhibit behaviors deviating from their traits to access relational resources. Narcissistic leaders emphasize self-interest (Liu et al. 2017; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). To conserve their resources (e.g., time and energy), they may purposefully opt to maximize their resources by forging strong ties with a small number of “trustworthy, loyal, and talented” subordinates, while maintaining a distance from the majority (i.e., maintaining resources). This differential treatment of team members by the leader increases team chaxu climate (Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019).

Furthermore, we postulate that a high level of team chaxu climate diminishes employees’ COCB. Most types of OCB do not carry the risk of offending leaders or colleagues, and hence, employees engage in these types of OCB without much consideration (Bettencourt 2004; Choi 2007). However, COCB may cause trouble for employees. Fundamentally, COCB is a proactive behavior aimed at improving organizational performance by challenging the organizational status quo, which may cause leaders to experience a sense of unhappiness and anger and deteriorate employees’ rapport with leaders (Bettencourt, 2004). We believe that people both inside and outside the circle are reluctant to engage in COCB because it is a high-risk behavior. In teams characterized by high levels of team chaxu climate, leaders exclusively provide key work resources to individuals within the “inner circle”—that is, the “insiders” (Liu et al. 2009). However, the relationship between “insiders” and “outsiders” is transient: Employees who cultivate positive relationships with leaders (for example, by affirming their views and following their instructions) may become “insiders” (Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019). Therefore, employees strive to be “insiders,” for whom, maintaining a positive relationship with the leader is a prerequisite for obtaining access to more job resources (Liu et al. 2009); thus, they are less likely to engage in COCB as doing so might upset the leader. On the contrary, for “outsiders,” provoking the leader might diminish their likelihood of entering the inner circle (Liu et al. 2009). They might refrain from COCB to obtain access to the inner circle for more resources. Therefore, we believe that “insiders” and “outsiders”—to preserve their resources and expand their access to resources—would not engage in COCB as doing so increases the risk of offending leaders.

Additionally, our hypotheses’ premise is that narcissistic leaders develop close relationships with team members only when they lack relational resources. Therefore, relational resources are key to narcissistic leaders developing close relationships with their team members. Further, related research has indicated that leaders’ attitudes toward subordinates are affected by their relationship with their supervisors as well as coworkers (Huang et al. 2020; Tafvelin et al. 2019). Unfortunately, the role of other factors (e.g., family) has rarely been considered. An individual’s behavior in the workplace is influenced by both the work environment and familial factors (Bozoğlu Batı and Armutlulu 2020; Staines 1980). Specifically, Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012) proposed the W–HR model, which describes how individual resources (e.g., time, energy, and affect) link one area’s demands and resources to the other area’s outcomes. Moreover, empirical studies have indicated that individuals’ lack of relational resources in the family causes individuals to seek alternatives in the workplace (Liu et al. 2015; Tsang et al. 2023; Witt and Carlson 2006). Therefore, we believe that considering family factors’ impact on narcissistic leadership behavior can help obtain a more comprehensive understanding of their behavioral motivations. According to COR theory, individuals experiencing the stress of resource loss are motivated to gain resources elsewhere (Hobfoll 1989; Hobfoll et al. 2018)—consistent with the W–HR perspective. Hence, we introduced family affective support as a moderating variable and posited that when narcissistic leaders cannot obtain adequate affective support at home, they become more likely to seek relational resources at work to compensate for this lack, such as by establishing fulfilling relationships with—and obtaining praise and admiration from—specific subordinates at work to alleviate the stress of resource loss at home. This behavior of narcissistic leaders precipitates team chaxu climate, which, in turn, affects employees’ COCB.

Our study makes several contributions. First, based on COR theory, we analyzed why narcissistic leaders develop deviant behaviors: Notably, narcissistic leaders develop high-quality relationships with some team members to acquire relational resources and maintain distant relationships with the majority to preserve these resources; this finding enhances our understanding of narcissistic leaders. Second, we build on COR theory to elucidate how narcissistic leadership affects employees’ COCB. Narcissistic leadership precipitates team chaxu climate owing to the discriminatory treatment of employees therein. This team chaxu climate, in turn, prevents employees from engaging in COCB, which carries a high risk of adversely impacting the leader–employee relationship. This possibly explains previous studies’ contradictory results regarding the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ OCB. That is, narcissistic leadership may discourage employees from engaging in challenging and transformative OCBs. Third, we employ the W–HR perspective to introduce leaders’ family affective support as a boundary condition in our research model. We demonstrated that the family emotional support received by narcissistic leaders is critical to whether they develop a small number of cronies in the work team, thus extending the boundary conditions for narcissistic leadership behavior and empirically validating the W–HR model.

Theory and hypotheses

Narcissistic leadership and employees’ COCB

The concept of “narcissism” originates from the ancient Greek myth that a young man named Narcissus fell in love with his reflection in the pool and finally perished because of his over self-preoccupation (Campbell et al. 2011). Ellis (1898) used the term “narcissism” to elucidate a pathological state of “twisted” self-affection. Subsequently, Freud (1939) proposed a distinct personality type characterized by an externally composed demeanor, assurance, and, at times, a sense of superiority. Horney (1939) expanded on this notion, suggesting that the traits exhibited by individuals with narcissistic tendencies—such as self-aggrandizement, excessively high self-regard, and the expectation of admiration from others—are rooted in qualities that they lack. Further, scholars have theorized that narcissism is a personality disorder. According to Kernberg (1967), narcissists are excessively preoccupied with the self, desperately need others’ admiration, are skilled at exploiting others, and lack empathy. By contrast, Kohut (1996) postulated that narcissism is not inherently pathological but follows a developmental trajectory. Healthy narcissism contributes to positive traits, such as humor and creativity, whereas pathological narcissism occurs when an individual cannot reconcile idealized self-beliefs with personal inadequacies, resulting in a lifelong search for validation from an idealized parental figure. Subsequent research has followed this line of reasoning. For example, Morf and Rhodewalt (2001b) considered narcissism a personality trait characterized by an inflated ego, dysfunctional interpersonal relationships, and a willingness to exploit others to enhance the self. Further, Campbell et al. (2011) suggest that individuals with narcissistic traits exhibit excessive self-confidence, extraversion, high self-esteem, a strong desire for attention, and an initial charm in interpersonal interactions. However, they are resistant to criticism, possess a pronounced sense of superiority, lack empathy, are willing to exploit others, and exhibit arrogance and grandiosity (Alsawalqa 2020; Campbell et al. 2011).

Researchers investigating the relationship between narcissism and leadership behavior have found that narcissists—compared to non-narcissists—are more likely to self-promote and self-nominate (Hogan et al. 1990) and are more likely to be leaders in general but less likely to communicate effectively with subordinates (de Vries and Miller 1985; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). de Vries and Miller (1985) highlighted narcissistic leadership’s duality, noting that some leaders evoke perceptions of strength, authority, and concern, whereas others evoke memories of intimidation, malevolence, and harm. Rosenthal and Pittinsky (2006) summarized past research pertaining to the relationship between narcissism and leadership and introduced the concept of narcissistic leadership. They held that narcissistic leaders are apathetic to others’ interests and act to suit their grandiose notions and arrogant desires. Generally, they cannot build long-term, deep relationships with others owing to their arrogance (Paulhus 1998; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). They frequently disregard others’ advice, take credit for their successes, blame others for their failures (Hogan et al. 1990), and constantly seek validation and superiority (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001a, 2001b; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). However, narcissistic leaders also have a charming side as they can enhance short-term staff motivation by exuding confidence and presenting a grand vision (Ouimet 2010). Fatfouta (2019) summarized the advantageous and disadvantageous aspects of narcissistic leadership. On the one hand, narcissists’ positive attributes (e.g., charisma) are linked to favorable results across levels, ranging from subordinates to peers to the entire organization. On the other hand, narcissists’ negative traits (e.g., entitlement) are correlated with numerous counterproductive work behaviors, which disrupt organizational performance (Fatfouta 2019).

Smith et al. (1983) introduced the term “organizational citizenship behaviors.” They argue that citizenship behaviors include both altruism and generalized compliance. Altruism is a class of helping behaviors aimed directly at specific individuals, while generalized compliance refers to an objective responsibility to make the organization operate more smoothly. Notably, OCB is significant in organizations and not easily explainable by the incentives that conformity to contractual role prescriptions and high production (Bateman and Organ 1983; Smith et al. 1983). Subsequently, Organ (1988) defined OCB as voluntary individual behavior that is not immediately or expressly rewarded by the formal reward system and that contributes to the organization’s efficient functioning. Characteristic examples of organizational citizenship behaviors include demonstrating concern for the organization’s reputation and goals, offering positive and helpful feedback, and actively participating in advancing the organization (Bateman and Organ 1983; Organ 1988; Smith et al. 1983). Further, employees’ OCB has been receiving a great deal of attention because it can significantly benefit an organization (Bettencourt 2004; Mackenzie et al. 2011; Organ 1988, 2018; Smith et al. 1983). Numerous previous studies on OCB have investigated affiliative behaviors, including interpersonal helping, courtesy, and compliance, which solely aim to maintain and strengthen the existing situation (Choi 2007). Owing to OCB research’s abundance, several behaviors aimed at changing the status quo have been classified as OCB. Subsequently, Bettencourt (2004) introduced the concept of COCB—an OCB that emphasizes challenging and transforming the existing situation. Choi (2007) elucidated this concept as the constructive effort invested by employees toward the processes and policy systems at work to optimize their performance—manifested by proposing recommendations for process improvement or implementing new working methods. Moreover, COCB has been proven to improve the organization’s efficiency and competitiveness (Mackenzie et al. 2011). Narcissistic leaders emphasize superiority, authority, and control (Maccoby, 2000); are keen to dominate others (Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006); and frequently deny others’ ideas and suggestions (Hogan et al. 1990; Huang et al. 2020). This can result in employees being reluctant to propose their ideas (Liu et al. 2017). Additionally, narcissistic leaders frequently pursue their self-interest through manipulation and exploitation, and take credit for their subordinates’ ideas and contributions, precipitating a reduction in employees’ drive for change (Locke 2009) and, consequently, in subsequent OCBs (Wang et al. 2021). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Narcissistic leadership significantly negatively impacts employees’ COCB.

Team chaxu climate’s mediating role

The concept of chaxu climate—a term originally introduced by Fei (1948)—has been derived from the indigenous Chinese notion of a chaxu pattern in society. He posited that traditional Chinese society is marked by a chaxu pattern, whereby individuals are central and their interpersonal relationships radiate outward in concentric “ripple circles.” As these circles widen, interpersonal relationships’ intimacy gradually diminishes; consequently, individuals at the center engage differently with those around them (Fei 1948). Zheng (1995) introduced the concept of the chaxu pattern into organizational research, positing that organizational leaders classify subordinates into “insiders” and “outsiders” based on three criteria—namely, the nature of their “guanxi” (a Chinese term for personal connections or relationships), the employee’s degree of loyalty, and their competence level. Liu (2003) observed that the chaxu pattern prevalent in Chinese society may result in leaders treating employees disparately, potentially cultivating a chaxu climate within teams. Focusing on work teams, Liu et al. (2009) suggested that team-level chaxu climate is determined by the variance in close relationships between team members and team leaders, with the latter usually controlling the resources. Subordinates with closer ties to team leaders are provided more power and resources (Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019). Chinese leaders tend to segment employees into “insiders” and “outsiders,” treating them differently in terms of providing opportunities and distributing resources, thereby cultivating a prevalent chaxu climate in Chinese organizations (Peng and Zhao 2011; Chen and Dian 2018; He et al. 2022). These studies indicate that leaders’ differential treatment of subordinates is closely related to team chaxu climate’s emergence.

Prior research has indicated that narcissistic leaders fail to create quality relationships with subordinates (Hogan et al. 1990; Maccoby 2000; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006); however, recent research has demonstrated that narcissistic leaders may exhibit deviant behavior, such as demonstrating compassion for subordinates or involving subordinates in key decisions (Carnevale et al. 2018; Owens et al. 2015). However, they do not create solid social relationships with all employees; instead, they choose a select few to establish a high-quality relationship with and alienate the majority (Huang et al. 2020). This is consistent with COR theory, which holds that individuals strategically utilize their limited resources to optimize valued resources’ accumulation—notably, in forming and maintaining social relationships. Individuals are incentivized to obtain respect and affective support as important psychological resources (Hobfoll 1989; Hobfoll et al. 2018; Hobfoll and Shirom 2001). Narcissists rely heavily on developing psychological resources, have a strong need for self-esteem and superiority, and desire to establish a grandiose self-image (Hogan et al. 1990; Horney 1939; Kernberg 1967; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). Hence, they tend to interact more frequently with those who praise and admire them than with those who do not (Brown 1997; Campbell et al. 2002; Gauglitz et al. 2023). Additionally, narcissistic leaders pursue superiority in a long-term, holistic manner (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001a, 2001b) and need to alienate most of their subordinates to preserve their superiority (Bernerth 2022; Huang et al. 2020). Moreover, building relationships with others requires time, effort, and other resources (Halbesleben et al. 2014). Hence, being on amicable terms with all subordinates may not be worthwhile for narcissistic leaders. Therefore, narcissistic leaders cultivate subordinates who can provide them with psychological resources as “henchmen” and, concurrently, decrease engagement with subordinates who cannot provide resources to protect their limited resources. This differential treatment of subordinates by narcissistic leadership increases the team chaxu climate.

Relevant studies have indicated that when the team chaxu climate is high, the work resources available to team members are unequal, and some members—those having a desirable relationship with the leader—receive more resources. By contrast, if the team chaxu climate is low, no significant difference exists in the resources available to all members (Liu et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019). In Chinese organizations, employees’ relationships with leaders affect the allocation of work resources (Chen and Dian, 2018; Liu et al. 2008). Leaders tend to allocate more work resources to employees with whom they have a desirable relationship (Liu et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009). This behavior often elevates the team chaxu climate (Liu et al. 2009). Related research has demonstrated that employees who are disadvantaged in organizational resource allocation may be less likely to exhibit motivation for change behaviors and neglect areas of improvement at work (Abdullah and Wider 2022). This is consistent with COR theory’s postulation that employees only act if they obtain resources in return for their invested effort (Hobfoll 1989; Hobfoll et al. 2018; Hobfoll and Shirom 2001). Therefore, we believe that when team chaxu climate is high, both “insiders” and “outsiders” abandon COCB after evaluating the return on their investment of resources. Specifically, “insiders”—who have a high-quality relationship with their narcissistic leader—receive more resources than other employees do because of this relationship (Liu et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009). Their optimal strategy involves maintaining a satisfactory relationship with their leader (Liu et al. 2009). However, COCB deviates from established protocols and may also be deemed unmanageable by the leader, causing the leader to lose trust in the employee and thereby deteriorating the leader–employee relationship (Bettencourt 2004). Moreover, the identity of the “insider” is unstable, and at any time, insiders and outsiders may interchange identities (Liu et al. 2009). Employees must maintain positive relationships with leaders to preserve their “insider” identity (Shen et al. 2019). Therefore, COCB is an unwise choice for them. “Outsiders”—who are estranged from their leaders—receive relatively few resources (especially core resources) and are at a relative disadvantage in the team, which reduces their motivation, psychological security, organizational identity, and emotional commitment (Liu et al. 2009; Opoku et al. 2020; Stinglhamber et al. 2021; Zhao et al. 2019). However, job resources, motivation, psychological safety, organizational identification, and emotional commitment are significant for employees to engage in COCB (Choi 2007; De Clercq 2022; Hu et al. 2023; Koopman et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2021). On the contrary, narcissistic leaders enjoy others’ praise and admiration (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001a, 2001b; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006); for employees, obeying leaders’ instructions and agreeing with their ideas is frequently a safer “to-be-inside” technique than COCB, which carries a high risk of adversely impacting the leader–employee relationship.

In summary, we suggest that narcissistic leadership precipitates team chaxu climate owing to differentiated relational strategies for different employees, which hinders employee COCB. Accordingly, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 2. Narcissistic leadership impacts employees’ COCB through team chaxu climate.

Family affective support’s moderating role

As postulated earlier, when narcissistic leaders lack relational resources, they develop desirable relationships with some team members. Moreover, relevant studies have confirmed that the adequacy of leaders’ relational resources affects their behavior. For example, Tafvelin et al. (2019) reported that coworker support affects leaders’ behavior at work. Huang et al. (2020) revealed that the quality of the exchange relationship between narcissistic leaders and their superiors influences their attitude toward their subordinates. This aligns with COR theory’s perspective that when individuals fail to receive the resources that they value through some social connections, they choose to seek these resources in other relationships to compensate for the risk of resource loss (Hobfoll et al. 2018; Wilson et al. 2010). These studies provide valuable insights into our understanding of narcissistic leadership behavior. However, prior research has focused solely on organizational factors and neglected the potential impact of leaders’ family-related factors. The work–family relationship model asserts that individuals’ familial and professional statuses impact each other, and they seek the experiences that they cannot obtain in one system from the other (Staines 1980). Particularly, Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker (2012) introduced COR theory into the work–family relationship model to construct a W–HR model to illustrate how individual resources (e.g., time, energy, and affect) connect the demands and resources of one domain to outcomes in the other domain. The W–HR model suggests that individuals’ resource adequacy status in the family domain affects their attitudes and behaviors in the work domain, and vice versa (Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012). Moreover, subsequent empirical research has supported this idea. For example, Huffman et al.’s (2014) four-year longitudinal study revealed that employees with high—than those with low—spouse career support exhibit higher job satisfaction and lower turnover rates. Cheng et al.’s (2019) COR-theory-based study demonstrated that family stress can cause disruptive behaviors at work. Furthermore, Bozoğlu Batı and Armutlulu’s (2020) study underscored that family–work conflict affects entrepreneurs’ investment decisions.

Narcissistic leaders tend to be highly egotistical and are more sensitive to the risk of resource loss (Maccoby 2000). If they do not receive adequate affective support from their family, they might exhibit anxiety and depression (Bushman and Baumeister 1998; Miller et al. 2007) and become likely to seek the fulfillment of their psychological resources through other means; meanwhile, subordinates’ respect, admiration, and loyalty is an effective countermeasure against the risk of resource loss (Huang et al. 2020). Considering COR theory and the W–HR model, we propose that the relationship between narcissistic leadership and team chaxu climate may be influenced by family affective support.

When narcissistic leaders’ family emotional support is low, the lack of affective resources may cause them to experience resource deprivation stress (Bushman and Baumeister 1998; Miller et al. 2007); to compensate for this lack, they may try creating “cronies” in their work team (Bernerth 2022; Huang et al. 2020). Further, the risk of resource loss created by a lack of family affective support makes narcissistic leaders particularly sensitive to resource investment (Hobfoll et al. 2018); hence, narcissistic leaders—to maintain their inadequate resources—alienate subordinates who cannot contribute resources to them (Huang et al. 2020). On the contrary, when certain needs of an individual are satisfied, other needs are increasingly prioritized (Maslow, 1943). Thus, when narcissistic leaders receive higher family affective support, their relational resources are satisfied, and the psychological resources obtained by establishing high-quality relationships with subordinates become less effective. In this phase, their concern predominantly pertains to preserving a favorable self-image, gratifying their sense of superiority, and isolating themselves from all subordinates (Huang et al. 2020; Morf and Rhodewalt 2001a, 2001b). That is, when narcissistic leaders receive high family affective support, they alienate all subordinates to maintain their sense of superiority; consequently, team chaxu climate is alleviated. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Family affective support moderates leadership narcissism’s positive effect on the chaxu climate, with the positive effect being stronger when family affective support is low.

As discussed earlier, narcissistic leaders impact employees’ COCB via team chaxu climate, whose influence is moderated by leaders’ family affective support. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Family affective support moderates the team chaxu climate’s mediating effect. The stronger the family affective support, the weaker the team chaxu climate’s mediating effect.

Accordingly, this study’s research model can be developed (Fig. 1).

Method

Sample and procedure

We administered a three-wave time-lagged questionnaire with the assistance of in-service MBA students (full-time employees pursuing weekend MBA courses) from two universities in central China. Specifically, we sent invitations to 267 MBA students with the assistance of the MBA teaching centers at both schools; the respondents were asked regarding their willingness to participate in the survey and whether their team fulfilled the criteria for participation in this study. The inclusion criteria for the respondents’ team were threefold: The respondents’ team must (1) be a formal team in the organization, (2) collaborate to complete work tasks, and (3) exhibit a need for innovation in the work tasks. Notably, 84 eligible working MBA students confirmed their consent to participate in this survey. We utilized SoJump (a professional survey agency) to administer the online survey; we entrusted the recruited students to distribute the online questionnaires to their respective work teams. Specifically, each student was requested to distribute three or more questionnaires to their respective work teams. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured that their responses would remain confidential and that they could withdraw at any time. At Time 1, we asked the 84 students to distribute questionnaires among their team leaders to collect data on their narcissistic leadership tendencies and level of family affective support; we received 74 valid questionnaires. At Time 2 (two weeks after Time 1), questionnaires were distributed among the 74 teams to collect data on team chaxu climate; we received 408 valid questionnaires from 68 teams. At Time 3 (two weeks after Time 2), questionnaires were distributed among the 68 teams to collect data on employees’ COCB; we received 363 valid questionnaires from 61 teams. The leaders’ sample included 43 men (70.5%)—primarily aged 26–35 (N = 35, 57.4%) and 36–45 (N = 21, 34.4%) years—and the majority had been in their positions for 6–10 years (N = 46, 75.2%). Of them, 60 (98.4%) held a bachelor’s degree or higher. The employees’ sample included 188 men (51.8%)—most of whom were aged 26–35 (N = 148, 40.8%) and 36–45 (N = 152, 41.9%) years; their average tenure was 3–5 years (N = 164, 45.2%), and 285 of them had a bachelor’s degree or higher (78.5%).

We performed independent samples t-tests for team chaxu climate as well as for the control variables. The results indicated no significant difference between respondents who answered the questionnaire only at T2 and those who did so at both T2 and T3. Team chaxu climate (t = −1.566, p > 0.05), gender (t = −0.476, p > 0.05), age (t = 0.142, p > 0.05), educational level (t = −1.024, p > 0.05), and tenure (t = 0.217, p > 0.05). Additionally, the χ2 test’s results revealed no significant difference between the above two groups of respondents (gender: χ2 [1, N = 408] = 0.227, p > 0.05; age: χ2 [3, N = 408] = 0.769, p > 0.05; educational level: χ2 [3, N = 408] = 4.052, p > 0.05; tenure: χ2 [4, N = 408] = 2.281, p > 0.05).

Measures

In this study, items pertaining to narcissistic leadership and COCB were translated from English to Chinese using a translation/back translation technique; all questions were handled by one English-proficient professor and two doctoral students collaboratively and assessed on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Narcissistic leadership

Jonason, Webster’s (2010) scale, which has been demonstrated to have high-quality reliability and validity in the Chinese context, was used to measure narcissistic leadership (Li and Zhang 2018; Zhang et al. 2017). This scale comprises four items. An example item is “I tend to seek prestige or status.” In this study, the Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.866.

Team chaxu climate

Team chaxu climate was measured using Liu’s (2003) 10-item scale, which is scored by members of a team. This scale—developed in the Chinese context—is currently the most commonly utilized scale for measuring team chaxu climate (Liu et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2019). An example item is “My manager has a great deal of contact and interaction with specific subordinates on the team.” In this study, the Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.838. We aggregate the team-level chaxu climate; the analysis results are consistent with applicable standards, whereby the ICC1 value is 0.415, surpassing the standard of 0.12. The ICC2 value is 0.808, which exceeds the standard of 0.70. The average Rwg is 0.966, exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.70 (Bliese 2000).

COCB

COCB was measured using Choi’s (2007) scale, which comprises four items; an example item is “I frequently come up with new ideas or work methods to perform my tasks.” Numerous related studies have demonstrated the validity and reliability of this scale, which has been widely accepted by scholars (Ha et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2023). In this study, the Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.797.

Family affective support

Family affective support was measured using the scale edited by Li and Zhao (2009), which comprises six items; an example item is “When I am exhausted by work, my family is always encouraging.” This scale was developed based on the Chinese context and is highly compatible with Chinese customs. It has exhibited high reliability and validity in previous studies (Li and Zhao 2009; Shi and Wang 2016). In this study, the Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.919.

Control Variables

To exclude potential factors’ influence on the outcome variables, following prior research, we used the leader’s gender, age, educational level, and organizational tenure as control variables (Huang et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2022).

Data analysis

First, we performed Harman’s one-factor test and the Unmeasured Latent Method Construct (ULMC) to test common method biases (CMBs). Second, we incorporated variables across multiple levels. To establish discriminant validity, we conducted multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) using Mplus 7.4. Third, we constructed a multi-level structural equation model to assess the theoretical hypotheses. Finally, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation with 100,000 replications using R version 1.3.1 to further examine the mediation and moderated mediation effects.

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses and common method bias test

We used Mplus7.4 to run an MCFA to detect the discriminant validity between the constructs. As Table 1 indicates, the four-factor model (χ2 = 330.015, df = 248, χ2/df = 1.331; CFI = 0.929; TLI = 0.920, RMSEA = 0.030, SRMR [within] = 0.015; SRMR [between] = 0.084) exhibits a significantly better fitting index than other alternative models, suggesting that our study’s key variables are distinguishable.

We employed two methods to test for CMB. First, the results of Harman’s one-factor test revealed that the first factor before rotation explained only 24.133% of the total variation, which did not exceed the 40% threshold. Second, the unmeasured latent method construct was used to assess the CMB. After adding the common method factor, the five-factor model’s fit (χ2 = 299.927, df = 232, χ2/df = 1.293, CFI = 0.941, TLI = 0.929, RMSEA = 0.028, SRMR [within] = 0.015, SRMR [between] = 0.088) did not significantly improve, compared to the four-factor model. Collectively, these two methods indicate that the CMB in this study has been effectively controlled to a certain extent.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 2 presents the correlations, means, and standard deviations.

Hypotheses testing

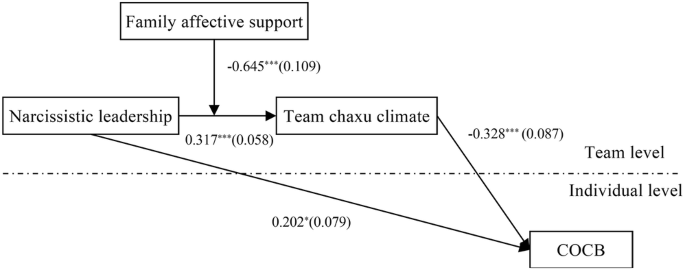

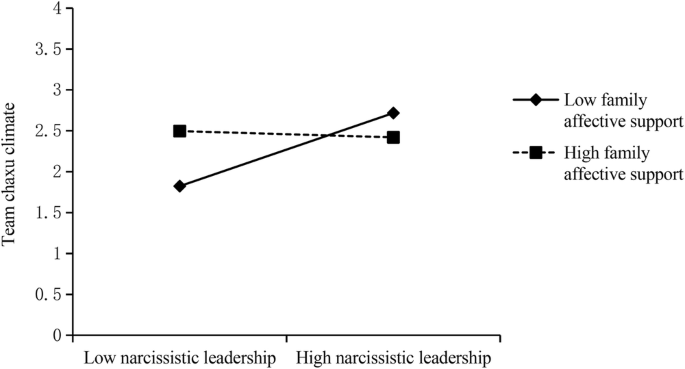

Figure 2 presents the results of the multilevel structural equation modeling analysis. Narcissistic leadership significantly positively impacted team chaxu climate (β = 0.317, p < 0.001), and team chaxu climate significantly negatively impacted employees’ COCB (β = −0.328, p < 0.001); thus, H2 is supported. The interaction term of narcissistic leadership and family affective support significantly impacted team chaxu climate (β = −0.645, p < 0.001); thus, H3 is supported.

The interaction in Fig. 3 illustrates that when leaders’ family affective support is strong, narcissistic leadership’s impact on the team chaxu climate weakens.

Table 3 presents the results of the Monte Carlo simulation with 100,000 replications. Evidently, narcissistic leadership’s indirect effect on employees’ COCB through team chaxu climate was significant (−0.104, 95%CI [−0.153, −0.061]). Therefore, H2 is further supported. Under high family affective support (mean +1 SD), narcissistic leadership’s indirect mediating effect on employees’ COCB through team chaxu climate was not significant (0.019, 95%CI [−0.0656, 0.001]). Under low family affective support (mean −1 SD), the indirect effect was significant (−0.228, 95%CI [−0.145, −0.063]). The effect size of the difference between high and low family affective support was significant (0.247, 95%CI [0.057, 0.084]), indicating that narcissistic leadership’s indirect effect on employees’ COCB through team chaxu climate was moderated by family affective support, thus supporting H4. Narcissistic leadership’s total effect on employees’ COCB was significant (−0.306, 95%CI [−0.375, −0.239]); hence, H1 is supported.

Discussion

Based on conservation of resources theory and the W–FR model, we constructed a multilevel moderated mediation model to explore how and when narcissistic leadership impacts employees’ COCB. We used team chaxu climate as a mediating variable in the relationship between narcissistic leadership and COCB to reveal the underlying mechanisms. Additionally, we explored family emotional support’s moderating role therein.

Utilizing a three-stage time-lag questionnaire, we found that narcissistic leadership negatively influences employee COCB—consistent with previous research on the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employee OCB (Ha et al. 2020; Li and Zhang 2018; Wang et al. 2021). On the one hand, COCB carries the risk of offending leaders (Bettencourt 2004; Choi 2007); on the other hand, narcissistic leaders may take credit for their subordinates’ contributions (Hogan et al. 1990). Consequently, employees are reluctant to engage in COCB. Moreover, team chaxu climate’s mediating role was supported. From a COR perspective, narcissistic leaders tend to maintain positive relationships with a select few valuable employees within their teams to gain access to relational resources, thus precipitating team chaxu climate, which, in turn, discourages team members from engaging in COCB. This explains not only why narcissistic leaders exhibit deviant behavior but also how narcissistic leadership affects employee COCB. Notably, family affective support moderates the relationship between narcissistic leadership and team chaxu climate: The stronger the family affective support received by leaders, the weaker the negative relationship between narcissistic leadership and team chaxu climate. That is, when narcissistic leaders receive sufficient affective support from their families, their need for a grandiose image outweighs their relational needs, at which point narcissistic leaders no longer need to develop relationships with a select few employees in their team to access relational resources. This corroborates the idea that a leader’s relationship with others affects their attitudes and behaviors toward subordinates (Huang et al. 2020; Tafvelin et al. 2019). Our study not only expands the boundary conditions for narcissistic leadership’s effects on employee behavior but also contributes to the W–HR model’s development.

Theoretical contributions

Our study contributes to the literature on OCB, team chaxu climate, and narcissistic leadership. First, our finding that narcissistic leaders develop relationships with their employees to acquire relational resources deepens the understanding of narcissistic leadership behavior. Earlier research argued that narcissistic leaders are selfish, arrogant, and lacking empathy, and that they fail to develop satisfactory relationships with their employees (Hogan et al. 1990; Maccoby 2000; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006). However, recent research has reported that narcissistic leaders proactively develop positive relationships with their employees and involve them in significant decisions (Carnevale et al. 2018; Owens et al. 2015). This is contrary to our previous knowledge pertaining to narcissistic leaders. However, why narcissistic leaders engage in such behavior, which deviates from their personality, has not been elucidated. Our study—based on COR theory—explains why narcissistic leaders develop relationships with their employees; specifically, it highlights that narcissistic leaders need relational resources through praise and admiration from their subordinates. This elucidates the reasons driving narcissistic leaders’ deviant behaviors (Carnevale et al. 2018), thus deepening our understanding of narcissistic leadership.

Second, our study revealed team chaxu climate’s mediating role in the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ COCB, thereby helping us better understand the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ OCB. Previous research on the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ OCB has yielded inconsistent results (Carnevale et al. 2018; Ha et al. 2020; Wang 2021; Zhang et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2023), thereby underscoring the limited understanding of the association between these two constructs. To address this gap, we elucidate how narcissistic leaders impact employees’ COCB based on COR theory. Narcissistic leaders acquire and safeguard resources by favoring a select few individuals within their team to become “insiders” and alienate the majority. Such differential treatment of employees by narcissistic leaders intensifies the team chaxu climate. At this time, both the “insiders” with high-quality—and “outsiders” with low-quality—exchange relationships with leaders refrain from engaging in high-risk COCB to obtain or preserve (existing) resources. Here, we particularly emphasize the high risk associated with COCB. Unlike most milder forms of OCB, employee COCB challenges the status quo, which may be distasteful for leaders (Bettencourt 2004; Choi 2007; De Clercq 2022), and offending their leaders may place them under tremendous pressure of losing resources (Hobfoll et al. 2018; Zaccaro et al. 2001). Thus, both “insiders” and “outsiders” may be discouraged from engaging in such behaviors. Our study provides a possible explanation for prior research’s contradictory results on the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ OCB, deepens our understanding of this relationship, and also responds to the call for further in-depth research on team chaxu climate as a local variable (Chen and Dian 2018).

Third, we examine family affective support’s moderating effect, in response to Huang et al.’s (2020) call to explore the boundary conditions under which narcissistic leadership contributes to mitigating narcissistic leadership’s negative effects. Previous research has found that leaders’ stock of resources significantly impacts their behavior. If leaders do not have access to relational resources with their supervisors or coworkers, they look elsewhere to supplement their relational resources (Huang et al. 2020; Tafvelin et al. 2019). Nevertheless, research discussing how narcissistic leaders’ perceived level of family support impacts their work behaviors is scant. The W–HR model explains that individuals’ need for resources at either work or at home affects their attitudes and behaviors in the other domain (Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012). We draw on W–HR to explore how narcissistic leaders’ behavior at work changes when they do not receive sufficient emotional support at home. Reportedly, narcissistic leaders are extremely sensitive to the loss of resources (Maccoby 2000). When they do not receive sufficient affective support from their family, they actively seek the recognition of a select few subordinates and establish high-quality relationships with them to compensate for this lack; meanwhile, leaders who receive adequate family affective support maintain their sense of superiority in the first place and reduce their interaction with subordinates. In sum, this study deepens our understanding of narcissistic leadership behavior’s boundary conditions and empirically validates the W–HR model.

Practical implications

This study’s findings have the following implications for organizational practice: First, companies must recognize that narcissistic leadership negatively impacts employees’ COCB. Narcissistic leaders habitually reject others’ opinions to maintain a sense of superiority (Hogan et al. 1990) and may also take credit for their subordinates’ innovations (Hogan et al. 1990; Rosenthal and Pittinsky 2006), precipitating employees’ reluctance to engage in COCB. This indicates that narcissists are not suited for leadership positions. Consequently, to avoid narcissistic leadership’s negative effects, organizations should screen for narcissistic personality traits when considering individuals for leadership positions and avoid promoting excessively narcissistic individuals to such positions. Moreover, the leader candidate’s peers or subordinates should be asked to assess their narcissism level, as narcissists tend not to exhibit their excessive narcissistic tendencies in front of their superiors but might present their true selves in front of their peers or subordinates (Campbell et al. 2011).

Second, organizations should adopt measures to reduce team chaxu climate. Per previous research, team chaxu climate forms an evident “circle phenomenon” within the team, thus decreasing employees’ performance and OCB (Shen et al. 2019). Furthermore, we found that neither “insiders” nor “outsiders” engage in COCB if the team chaxu climate is high. Therefore, the organization’s top managers should adopt measures to prevent the development of team chaxu climate. For example, the implementation of a teamwork resource-sharing model and a combination of team and individual performance appraisals can help avoid narcissistic leadership’s negative effects as well as provide psychological and work resource support for employees’ COCB.

Third, organizations must focus on their team leaders’ relational resource status. Previous research has demonstrated that among narcissistic leaders, the experience of relational resource stress intensifies their personality’s negative aspects (Huang et al. 2020). Moreover, we found that when narcissistic leaders do not receive sufficient emotional support in their families, they treat subordinates within their team differently, thus developing team chaxu climate. This, in turn, reduces the likelihood of employees’ COCB. However, when narcissistic leaders are provided with sufficient relational resources in the family (family emotional support), they do not treat team employees differently and the negative effects disappear. This indicates that senior managers should focus more on—and provide greater support to—team leaders. For example, communicating more frequently with team leaders and extending goodwill and support can effectively mitigate their psychological pressure (Li et al. 2023).

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

This study has some limitations. First, although we collected data utilizing a multi-source and multi-wave approach, this study does not employ a rigorous longitudinal study design; hence, it cannot definitively determine the causal relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ COCB. Arguably, employees’ COCB may cause leaders to reflect on their narcissistic leadership behaviors, thus reducing such behaviors. Our research model is consistent with the theoretical ordering of variables in the input–process–output (I–P–O) framework (Mathieu and Taylor 2006): Team inputs (narcissistic leadership) impact team processes (team chaxu climate), which, in turn, impact output (COCB). Nevertheless, we encourage future scholars to conduct rigorous longitudinal studies or field trials to assess the causal relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ COCB.

Second, our study focused specifically on the relationship between narcissistic leadership and COCB—a risky behavior; however, most other OCBs are less risky (Bettencourt 2004). Future research must examine the relationship between narcissistic leadership and other types of OCBs. For example, how narcissistic leadership affects service-oriented OCBs. Understanding the relationship between narcissistic leadership and different types of OCBs can help us better explain prior studies’ inconsistent results regarding the relationship between narcissistic leadership and employees’ OCB.

Third, although our study revealed the moderating role of leaders’ family affective support, most current research focuses on intra-organizational factors’ impact on narcissistic leadership behaviors (Huang et al. 2020; Tafvelin et al. 2019). Research on extra-organizational factors’ impact on narcissistic leaders’ behavior in the workplace is scant. We encourage future research to examine extra-organizational situational factors that can impact narcissistic leadership behavior. For example, future research can examine whether narcissistic leaders—in high-uncertainty environments—develop positive relationships with all team members to maintain their status and ensure team performance. This can be useful in furthering the current understanding of narcissistic leaders.

Fourth, we focused solely on a singular category of employee contributions in relation to leadership behavior—namely, employees’ COCB. Other employee contributions may also be affected by narcissistic leadership and team chaxu climate. For example, team chaxu climate attributable to narcissistic leadership can cause members to distrust each other, thus decreasing team performance. We suggest that future research should examine these other outcomes of leader narcissism and the resultant team chaxu climate.

Finally, most sample data in this study originate from organizations in China; hence, regional culture may have influenced the findings. Specifically, the mean for narcissistic leaders in our sample was 2.77 (5-point scale)—somewhat different from sample means in other national studies. For example, the narcissistic leadership mean in Aboramadan et al.’s (2020) study was 3.57 (5-point scale) and that in Ghislieri et al.’s (2019) study was 2.31 (5-point scale), suggesting that leaders from different cultures exhibit different narcissism levels. Therefore, future studies should employ samples from different cultures to cross-validate this study’s findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MUZS1X).

References

Abdullah MR, Wider W (2022) The moderating effect of self-efficacy on supervisory support and organizational citizenship behavior. Front Psycho 13:961270. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022

Aboramadan M, Turkmenoglu MA, Dahleez KA, Cicek B (2020) Narcissistic leadership and behavioral cynicism in the hotel industry: the role of employee silence and negative workplace gossiping. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 33(2):428–447

Alsawalqa RO (2020) Emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism among physicians in Jordan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):1–12

Bateman TS, Organ DW (1983) Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee “citizenship”. Acad Manag J 26(4):587–595

Bernerth JB (2022) Does the narcissist (and those around him/her) pay a price for being narcissistic? An empirical study of leaders’ narcissism and well-being. J Busin Ethi 177(3):533–546

Bettencourt LA (2004) Change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors: The direct and moderating influence of goal orientation. J Retail 80(3):165–180

Bliese PD 2000 Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In: Klein KJ, Kozlowski SW (eds), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (349-381). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Bozoğlu Batı G, Armutlulu İH (2020) Work and family conflict analysis of female entrepreneurs in Turkey and classification with rough set theory. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7(1):1–12

Brown AD (1997) Narcissism, identity, and legitimacy. Acad Manag Rev 22(3):643–686

Brunell AB, Gentry WA, Campbell WK, Hoffman BJ, Kuhnert KW, DeMarree KG (2008) Leader emergence: The case of the narcissistic leader. Pers Soc Psychol B 34(12):1663–1676

Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF (1998) Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? J Pers Soc Psychol 75(1):219–229

Campbell WK, Hoffman BJ, Campbell SM, Marchisio G (2011) Narcissism in organizational contexts. Hum Resour Manag R 21(4):268–284

Campbell WK, Rudich EA, Sedikides C (2002) Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Pers Soc Psychol B 28(3):358–368

Carnevale JB, Huang L, Harms PD (2018) Leader consultation mitigates the harmful effects of leader narcissism: A belongingness perspective. Organ Behav Hum Dec 146:76–84

Chen Z, Dian Y (2018) Organizational chaxu climate: Concept, measurement and mechanism. Forei Econ Manag 40(6):86–98

Cheng B, Zhou X, Guo G (2019) Family-to-work spillover effects of family incivility on employee sabotage in the service industry. Int J Confl Manag 30(2):270–287

Choi JN (2007) Change‐oriented organizational citizenship behavior: effects of work environment characteristics and intervening psychological processes. J Organ behav 28(4):467–484

De Clercq D (2022) Organizational disidentification and change-oriented citizenship behavior. Eur Manag J 40(1):90–102

de Vries MFK, Miller D (1985) Narcissism and leadership: An object relations perspective. Hum Relat 38(6):583–601

Ellis H (1898) Auto-eroticism: A psychological study. Alienist Neurologist 19:260–299

Fatfouta R (2019) Facets of narcissism and leadership: A tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde? Hum Resour Manage R, 29(4), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.1010.1002

Fei X (1948) From the soil: The foundations of Chinese society. Shanghai Observatory, Shanghai

Freud S (1939) Libidinal Types. Collected papers, Vol. 5. Hogarth Press, London

Gauglitz IK, Schyns B, Fehn T, Schütz A (2023) The dark side of leader narcissism: the relationship between leaders’ narcissistic rivalry and abusive supervision. J Busin Ethi 185(1):169–184

Ghislieri C, Cortese CG, Molino M, Gatti P (2019) The relationships of meaningful work and narcissistic leadership with nurses’ job satisfaction. J Nurs Manag 27(8):1691–1699

Ha S-B, Lee S, Byun G, Dai Y (2020) Leader narcissism and subordinate change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: Overall justice as a moderator. Soc Behav Pers 48(7):1–12

Halbesleben JRB, Neveu JP, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M (2014) Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the Role of Resources in Conservation of Resources Theory. J Manag 40(5):1334–1364

He P, Wang J, Zhou H, Zhang C, Liu Q, Xie X (2022) Workplace friendship, employee well-being and knowledge hiding: The moderating role of the perception of Chaxu climate. Front Psychol 13:1036579. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1036579

Hobfoll SE (1989) Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychologist 44(3):513–524

Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M (2018) Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu Rev Organ 5(1):103–128

Hobfoll SE, Shirom A (2001) Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. Public Policy Adm 87:57–80

Hogan R, Raskin R, Fazzini D (1990) The dark side of charisma. In: Clark KE (ed) Measures of leadership (pp. 343–354).West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America

Horney K (1939) New ways in psychoanalysis. Norton, New York

Hu E, Han M, Zhang M, Huang L, Shan H (2023) Union influence on change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: evidence from China. Empl Relat 45(2):387–401

Huang L, Krasikova DV, Harms PD (2020) Avoiding or embracing social relationships? A conservation of resources perspective of leader narcissism, leader–member exchange differentiation, and follower voice. J Organ behav 41(1):77–92

Huffman AH, Casper WJ, Payne SC (2014) How does spouse career support relate to employee turnover? Work interfering with family and job satisfaction as mediators. J Organ behav 35(2):194–212

Jonason PK, Webster GD (2010) The dirty dozen: a concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol Asses 22(2):420–432

Kernberg O (1967) Borderline personality organization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 15(3):641–685

Kohut H (1996) Forms and transformations of narcissism. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 14(2):243–272

Koopman J, Lanaj K, Scott BA (2016) Integrating the bright and dark sides of OCB: A daily investigation of the benefits and costs of helping others. Acad Manag J 59(2):414–435

Li F, Chen T, Bai Y, Liden RC, Wong M-N, Qiao Y (2023) Serving while being energized (strained)? A dual-path model linking servant leadership to leader psychological strain and job performance. J Appl Psychol 108(4):660–675

Li YX, Zhao N (2009) Structure and measurement of work-family support and its moderation effect. Acta Psychol Sin 41(9):863–874

Li M, Zhang HYG (2018) How employees react to a narcissistic leader? The role of work stress in relationship between perceived leader narcissism and employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors to supervisor. Int J Ment Health Promot 20(3):83–97

Liu H, Chiang JT-J, Fehr R, Xu M, Wang S (2017) How do leaders react when treated unfairly? Leader narcissism and self-interested behavior in response to unfair treatment. J Appl Psychol 102(11):1590–1599

Liu J, Song J-W, Wu L-Z (2008) Antecedents of employee career development: An examination of politics and Guanxi. Acta Psychol Sin 40(2):201–209

Liu J, Zhang K, Zhong L (2009) The Formation and Impact of the Atmosphere of the “Error Routine” of the Work Team: a Case Study Based on Successive Data. Manag Wld 8:92–101+188

Liu Y, Wang M, Chang C-H, Shi J, Zhou L, Shao R (2015) Work–family conflict, emotional exhaustion, and displaced aggression toward others: The moderating roles of workplace interpersonal conflict and perceived managerial family support. J Appl Psychol 100(3):793–808

Liu Z (2003) The influence of diferential atmosphere on subordinates work attitudes and behaviors. National Dong Hwa University, Hualian

Locke KD (2009) Aggression, narcissism, self-esteem, and the attribution of desirable and humanizing traits to self versus others. J Pes Pers 43(1):99–102

Maccoby M (2000) Narcissistic leaders: The incredible pros, the inevitable cons. Harv Bus Revw 78(1):68–68

Mackenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Podsakoff NP (2011) Challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors and organizational effectiveness: Do challeng-oriented behaviors really have an impact on the organization’s bottom line? Pers Psycho 64(3):559–592

Maslow AH (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol Rev 50(4):370–396

Mathieu JE, Taylor SR (2006) Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. J Organ behav 27(8):1031–1056

Miller JD, Campbell WK, Pilkonis PA (2007) Narcissistic personality disorder: Relations with distress and functional impairment. Compr Psychiatry 48(2):170–177

Morf CC, Rhodewalt F (2001a) Expanding the dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism: Research directions for the future. Psycholl Inq 12(4):243–251

Morf CC, Rhodewalt F (2001b) Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psycholl Inq 12(4):177–196

Opoku MA, Choi SB, Kang S-W (2020) Psychological safety in Ghana: empirical analyses of antecedents and consequences. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(1), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010214

Organ DW (1988) Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington

Organ DW (2018) Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Annu Rev Organ 80:295–306

Ouimet G (2010) Dynamics of narcissistic leadership in organizations: Towards an integrated research model. J Manag Psychol 25(7):713–726

Owens BP, Wallace AS, Waldman DA (2015) Leader narcissism and follower outcomes: The counterbalancing effect of leader humility. J Appl Psychol 100(4):1203–1213

Paulhus DL (1998) Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? J Pers Soc Psychol 74(5):1197–1208

Peng ZL, Zhao HD (2011) Research of effect to team innovation performance from Chaxu calimate on knowledge transfer perspective. Stud Sci Sci 29(8):1207–1215

Rosenthal SA, Pittinsky TL (2006) Narcissistic leadership. leadersh Q 17(6):617–633

Shen Y, Zhu Y, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Liu J (2019) The influences of team differential atmosphere on team members’ performance: An investigation of moderated mediation model. Manag Wld 35(12):104–115+136+215

Shi G, Wang A (2016) The effects of leader-member fit and family emotion support on employees’ creativity: Test of a mediated moderator model. Mod Financ Econ 36(10):39–48

Smith CA, Organ DW, Near JP (1983) Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J Appl Psychol 68(4):653–663

Staines GL (1980) Spillover versus compensation: A review of the literature on the relationship between work and nonwork. Hum Relat 33(2):111–129

Stinglhamber F, Caesens G, Chalmagne B, Demoulin S, Maurage P (2021) Leader–member exchange and organizational dehumanization: The role of supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Eur Manag J 39(6):745–754

Tafvelin S, Nielsen K, von Thiele Schwarz U, Stenling A (2019) Leading well is a matter of resources: Leader vigour and peer support augments the relationship between transformational leadership and burnout. Work Stress 33(2):156–172

Ten Brummelhuis LL, Bakker AB (2012) A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. Am Psychologist 67(7):545–556

Tsang S-S, Liu Z-L, Nguyen TVT (2023) Family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity: do work engagement and self-efficacy mediate? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–13

Visser BA, Book AS, Volk AA (2017) Is Hillary dishonest and Donald narcissistic? A HEXACO analysis of the presidential candidates’ public personas. Pers Individ Dif 106:281–286

Wang L (2021) The Impact of Narcissistic Leader on Subordinates and Team Followership: Based on “Guanxi” Perspective. Front Psycho, 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.684380

Wang W, Jian L, Guo Q, Zhang H, Liu W (2021) Narcissistic supervision and employees’ change-oriented OCB. Manag Decis 59(9):2164–2182

Wilson KS, Sin H-P, Conlon DE (2010) What about the leader in leader-member exchange? The impact of resource exchanges and substitutability on the leader. Acad Manag Rev 35(3):358–372

Witt LA, Carlson DS (2006) The work-family interface and job performance: moderating effects of conscientiousness and perceived organizational support. J Occup Health Psychol 11(4):343–357

Zaccaro SJ, Rittman AL, Marks MA (2001) Team leadership. Leadersh Q 12(4):451–483

Zhang L, Lou M, Guan H (2022) How and when perceived leader narcissism impacts employee voice behavior: a social exchange perspective. J Manag Organ 28(1):77–98

Zhang L, Zhang L, Pei Y (2017) Influence mechanism of narcissistic leader’s doublesided trait on employee’s organizational citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. Tech Econ 36:68–78

Zhao H, Liu W, Li J, Yu X (2019) Leader–member exchange, organizational identification, and knowledge hiding: T he moderating role of relative leader–member exchange. J Organ behav 40(7):834–848

Zheng B (1995) Chaxu pattern and Chinese organizational behavior. Local Psychol Res 3:142–219. https://doi.org/10.6254/1995.3.142

Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Qin F, Li Y (2023) The Relationships of Leaders’ Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry with Nurses’ Organizational Citizenship Behavior towards Leaders: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J Nurs Manag, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/5263017

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yangchun Fang contributed to conceptualization, writing—review, and editing. Yonghua Liu contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, review, and editing. Peiling Yu contributed to investigation, writing—review, and editing. Nuo Chen contributed to investigation, methodology, and writing—review. All authors have read and agreed to the manuscript’s published version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the School of Management, Zhejiang University of Technology, in September 2023 (No. 2023092101).

Informed consent

All participants were informed regarding this study’s aim and scope as well as the ways in which the data would be used. The respondents’ participation was completely consensual, anonymous, and voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study before they participated in the survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, Y., Liu, Y., Yu, P. et al. How does narcissistic leadership influence change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior? Empirical evidence from China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 667 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03159-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03159-2

- Springer Nature Limited