Abstract

In the context of trade liberalization and new urbanization, it is important to study how urban openness leads to wage premiums and improvements in income distribution. This paper utilizes micro-data from the Chinese Household Income Project and matching data from 144 cities to investigate the relationship between trade liberalization, urban scale, and urban wage premiums. The results indicate that trade liberalization significantly increases urban wage premiums, which is particularly evident during the early stages of China’s accession to the WTO. However, this effect may fluctuate over time. Surprisingly, in China, the urban scale can increase labor wage income, but it does not magnify the wage premium effect of trade liberalization. Heterogeneity tests based on regions, firms, and income groups suggest that the wage premium effect of trade liberalization is higher in eastern and central region cities than in western region cities, labor wage growth in the service sector is more pronounced than in the industrial sector, and the impact of trade liberalization on wage growth for the middle and lower-income groups is greater than for the high-income group, which helps to narrow income disparities among different groups. These findings are of great policy significance for improving income distribution through labor market liberalization. In this context, they highlight the importance of comprehensive openness and new urbanization in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s continuing trade liberalization since the reform and opening up has contributed toward its economic development and global success, but it has also widened the income gap between regions. Maintaining a balance between the development of the export-oriented economy and improving income distribution has become a key economic issue in China. While trade liberalization promotes a country’s overall economic development and welfare level, it will also bring about regional labor market adjustment and revenue changes (Krisztina and Robert, 2015). Income inequality worsens when the transmission of trade liberalization is affected by different geographical locations, marketization, and infrastructural levels (Ian, 2006; Ni and Liu, 2019). As the spatial subject of economic development, the urban income imbalance constitutes the key source of the main social contradiction in the new era. It is crucial to explain this aspect from the perspective of urban wage premium and explore the income distribution and gap adjustment effects of trade liberalization.

Opening-up and trade liberalization are important models of the country’s economic development and a key path to improving national income and welfare. However, in many countries, especially developing countries, trade liberalization has led to an increase in the income gap and the Gini coefficient. These problems have prompted the Chinese academia to rethink the benefits and limitations of trade liberalization. There are two main literature branches related to this study—one focuses on wage premiums and income distribution from the perspective of trade liberalization, and the other focuses on the causes of wage premiums and the impact of income distribution from the urban perspective. The first branch is comprehensive in nature. Extending the analysis from two aspects of increasing wage and income distribution, on the one hand, researchers have examined the reasons behind the widening wage gap and its evolutionary trend in China (Serrano and Pinilla, 2014; Magnac and Roux, 2021; Pablo et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Castelán et al., 2022). On the other hand, they have examined the factors and effects of wage premiums from the perspective of macro and micro environments (Lu et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021). Trade liberalization has been analyzed mostly from the macro or meso perspective, using macro data such as Chinese industrial enterprise database, customs warehouse, wits tariff data, or world input-output data database (WIOD) to study export product quality, value chain, industrial upgrade, business growth, markup rate, employment, innovation (including technological), industrial structure upgrade, and the domestic added value of exports. Trade liberalization studies have also focused on the link between trade liberalization and environmental protection, fiscal expenditure, and the impact of trade liberalization on certain groups (Marjit and Acharyya, 2006; Rubiana and Sharma, 2011; Daiki,2019; Sunge and Ngepah, 2020; Michael et al., 2021). The measurement of trade liberalization has matured over the years. However, data and research methods inconsistency have produced inconclusive empirical results regarding the relationship between trade liberalization and individual wage income (Thurlow, 2007; Xie and Huang, 2020; Qi and Xi, 2023).

The second literature branch focuses on wage premiums from the perspective of cities, which are considered spatial clusters of economic development; in this context, studies have concentrated on economies of scale and agglomeration in cities. As an innovation environment, big cities promote activities such as face-to-face interaction, knowledge sharing, thought leadership, and new product development and designs. In this context, research has also focused on the size of cities. It demonstrates that city size affects workers’ wages through agglomeration and talent selection effects. First, the urban agglomeration effect can increase the wages of all workers through the labor pool effect, shared market, and knowledge or technology spillover effects; it can also promote regional wage differences (Li and Shao, 2017; Muthukumara et al., 2020). Second, the selection effect impacts the wage difference between cities through the location selection of laborers with different skills, which is mainly reflected in the left and right tails of the distribution of wages and skills. Labor mobility is highly sensitive to urban wages and employment rates (Combes et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2020). Several studies have simultaneously considered the wage gap between cities and the spatial agglomeration theory to analyze the impact of the spatial distribution of economic activities on urban wage levels.

Although the literature quantitatively analyzes urban population size and wage income, some gaps remain. First, research on the impact of urban size and trade liberalization on wage income is relatively independent—it does not consider the cross-effect of the two factors or the heterogeneity of the transmission of trade liberalization in cities of different sizes. Second, several studies have empirically analyzed the increasing wage income; however, they have failed to conduct a corresponding theoretical analysis and systematic investigation and equated agglomeration economies with population agglomeration. Finally, the measurement of trade liberalization has been limited to provincial and national levels. Wage gap research has focused on different groups, such as regions and industries, and it has rarely combined micro, meso, and macro data to consider the heterogeneity of individual income.

In the context of China’s active promotion of new urbanization and trade liberalization, this study conducts a micro-level spatial analysis of cities. We match personal micro-survey data with urban meso- and macro-trade data to refine the trade measurement of each city and measure the degree of openness and city size. The study uses these data to analyze the increase in individual wage income under the joint effect of trade liberalization and urban economy. The contributions of this study are as follows. First, scholars have mainly investigated the effects of trade liberalization at the industry and enterprise levels and discussed individual wage income from the perspective of city size and industrial agglomeration. The discussion of premiums is relatively rare. This study integrates trade liberalization, city size, and industrial agglomeration to analyze the wage gap of laborers, thus expanding the research on China’s urban open economy. Second, studies on China’s trade liberalization are based on industrial enterprise databases and the empirical testing of customs databases. There is a need to expand the research on urban wage premiums on the basis of micro-individual data. This study refines the measurement of trade liberalization at the city level and more accurately and comprehensively measures the status of trade openness in different cities based on the trade dependence or trade penetration rate of different cities. It also uses data from the China Household Income Survey (CHIP), along with micro and macro data, to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the heterogeneity of individuals, enterprises, and industries and compare the gap between workers’ wages.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: the section “Theoretical mechanism and research hypothesis” constructs the theoretical mechanism and puts forward the research hypothesis. Section “Model construction, variable description, and data processing” introduces the model, variable, and data. Section “Basic regression and robust test” reports and discusses the main results. Section “Transmission mechanism and analysis of the heterogeneity sample” conducts the test of the conduction mechanism. Section “Conclusions and implications” presents the main conclusions and offers related recommendations.

Theoretical mechanism and research hypothesis

Trade liberalization may be transmitted to the wage premium through various mechanisms, one of which is reflected in the significant role of deepening trade openness in developing diverse employment markets. The channels through which diverse employment markets affect wages are as follows. First, they affect enterprises’ choice of laborers. Owing to trade liberalization, more companies have gained market access, and the elimination rules for formal companies have become stricter. To maximize profits, formal companies reduce formal employment and seek more temporary workers or outsourcers. Often, the outsourced work entails low-tech repetitive mechanical labor, and hence, the salaries of contractors are lower than those of full-time employees. This can also be attributed to the wage penalty associated with informal recruitment methods adopted by small and micro enterprises. Nonetheless, contractual employees receive their wage premium. Second, diverse employment markets affect the position of the industrial chain of import and export enterprises in different industries. Trade liberalization has increased competition in the import and export sectors. However, export and import companies have not only strengthened vertical exchanges between midstream and downstream companies but have also expanded their market transactions. They have improved their employment structure and adjusted the wage levels of different labor groups in the global value chain.

Based on the above analysis, we propose Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: Trade liberalization is conducive to raising the income level of laborers, but the wage premium of workers in diverse employment markets is different.

However, trade liberalization may bring many indirect effects due to the spatial differences in urban agglomeration. Urban agglomeration affects labor income through the following channels. First, it encourages knowledge sharing, learning, and interaction among local laborers. A dense population provides individuals with more learning opportunities and improves their learning efficiency (Glaeser and Ressenger, 2010; Zhao et al., 2020). In such agglomerations, specialized and diversified enterprises enjoy higher productivity or skill levels, which directly contribute toward an increase in workers’ income. Second, in industrial agglomerations, enterprises can attract more talents that match the market requirements by providing a broader employment platform. These urban agglomerations expand enterprises’ human capital choices and provide them with a better space for trial and error; they also reduce the phenomenon of brain drain or overqualified or low-skilled labor taking the lead in remote areas due to information asymmetry and narrow markets. Third, the scale of cities contributes toward the formation of an agglomeration economy, which leads to economies of scale and a virtuous circle. Additionally, talent selection in a city determines the breadth of its employment opportunities for highly skilled workers. Large cities attract more highly skilled labor and accelerate human capital accumulation and investment realization. Naturally, these workers get higher wages (Thomas and Michael, 2012). This selection effect on talents is also reflected through the externalities of skill levels in large cities. They provide more avenues to avail skill training and host a higher number of training institutions and universities. Large cities not only cultivate a highly skilled workforce but also reduce the size of the low-skilled labor workforce. The focus on highly skilled labor drives the selection of high-level training courses to facilitate the rapid realization of human capital investment; some unselected labor groups will continue to engage in relatively mechanized and repetitive work, which will keep individual workers from joining the core workforce of large cities.

According to the above, we formulate Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: The size of the city has a magnifying effect on the wage skill premium associated with trade liberalization. The key transmission mechanisms of trade liberalization are the selection effect and the compensation earned as a result of specialization and diversification agglomeration of industries.

From a broader perspective, the talent selection effect of cities of different sizes affects the mechanism of the screening effect of trade liberalization capabilities, which may be heterogeneous. First, trade liberalization has a heterogeneous effect on wage premiums in cities in China’s eastern, central, and western regions. Trade liberalization has affected the urban–rural population mobility and the regional income structure. These regional differences have been reflected in the dual urban–rural structure in China. Given this, note that the floating populations are more willing to move to the eastern regions (Zhang et al., 2021). In general, the overall development level of cities in the eastern region is higher, and the demand for technical and non-technical labor in the industrial structure shows a differentiated trend. The larger urban labor market in the eastern region reflects its high demand for highly skilled technical labor to support free trade. China’s free trade reforms have also increased the wage premium. Second, although population mobility has increased the income levels in large cities, it has intensified the imbalance between supply and demand in the local labor market. The fierce competition among unskilled labor has contributed to their inability to obtain a high-wage income. The industrial structure has been continuously optimized during the process of trade liberalization as a large number of laborers migrated to cities. However, the surplus rural labor mostly comprises unskilled labor. Although they enter the urban labor market, very few match the job requirements in large cities, and skilled labor groups still obtain higher urban wage premiums. In addition, although the opening-up effect of trade liberalization affects the price preference of consumer goods, the rigidity of housing prices in big cities reduces the price demand elasticity of the consumer market (Li, 2017), and high-income workers receive more urban wage premiums from trade liberalization.

Based on the above analysis, Hypothesis 3 is proposed.

Hypothesis 3: The urban wage premium effect of trade liberalization is heterogeneous, and this effect is more significant on the labor force of the eastern region and highly skilled and high-income groups.

Model construction, variable description, and data processing

Model building

Since the reform and opening-up policy, China has been continuously promoting trade liberalization, contributing to economic development and global success. However, it has also led to the widening income gap between different regions. Finding a balance between developing an export-oriented economy and improving income distribution has become a key issue for the Chinese economy. Considering the current situation, trade liberalization not only promotes overall economic development and raises the welfare level, but also brings about labor market adjustments and income changes in different regions. As the main body of economic development, the imbalance of urban income has become an important source of social contradictions in the new era. In this context, it is crucial to explain this issue from the perspective of urban wage premiums and explore the income distribution and disparity adjustment effects of trade liberalization. Therefore, this article will refer to the practices of previous scholars and use the classic Mincer’s individual income equation to test the wage premium effect of trade liberalization. Furthermore, it will further explore the impact of urban scale on wage premiums under open conditions.

Where subscript i represents an individual, and c represents the city where i is located. lnwage is the logarithm of the average monthly income of workers, and csize represents the size of the city where the laborer is located. In the basic regression, csize is measured by the registered population of the city’s jurisdiction. open denotes the degree of trade liberalization; the larger the value of open, the higher the degree of trade liberalization. This measurement method has been used by many scholars (Liu and Li, 2012). open×csize denotes the interaction between trade liberalization and city size. Denoting the logarithm of the city’s GDP, lnpcgdp is used to control the level of economic development of the city. X denotes the control variable for the individual and the company and industry to which the individual belongs. This control variable ascertains whether the individual belongs to the Han nationality and includes the individual’s gender, age, age2, health level, education level, and marital status, among others. The control variables at the enterprise and industry levels cover enterprise ownership and size and the industry in which individuals work.

Main variables

Explained variables

The interpreted variable is the wage level of laborers denoted by lnwage, which is the logarithm of the explained variable. Wages are measured in yuan. In 2002, the CHIP questionnaire survey included the following response options: “Full-year income” and “did you work in 2002 for a few months?” However, the 2007 and 2008 questionnaires asked the participants to report their monthly salary income. The 2013 and 2018 questionnaire survey included the following options: “Total income from working in 2013 (2018) ” and “How many months did you work in 2013 (2018) ?” Based on the research purpose, this study adopts the logarithm of the monthly wage income to represent the income level. Due to the large amount of data, observations with wages less than zero are excluded. To ensure that the wage income of each region and each year can be compared, this study uses the provincial consumer price index for deflation; the data are procured from the National Bureau of Statistics. Since the sample period is 2002–2018, we use 2002 as the base period to deflate the nominal wages, excluding the factors of inflation, and obtain the actual wages of individual labor.

Explanatory variables

-

(1)

City size: We use the logarithm of the population in the municipal area to represent lncsize. The population size of the municipal jurisdiction over a period is taken from《China City Statistical Yearbook》. The city code count is provided in the CHIP survey data. We match the unified zonal and urban–rural division codes published by《National Bureau of Statistics》, and each code represents a city. Owing to the free flow of production factors within the city, CHIP provides codes for each district in Beijing, Chongqing, and other municipalities, this study classifies each district under Beijing and Chongqing and does not distinguish them. There may be a two-way causal relationship between city size and wage income—that is, the relatively high wages provided by large cities attract labor, and labor inflows contribute toward the expansion of the city size. Therefore, as an instrumental variable, this study selects the urban construction area in 2003; the data are taken from the statistical database of China Economic Net. The urban construction area is directly related to the size of the urban space, but not to the wage of laborers. Therefore, it can be used as an instrumental variable for the size of the urban population.

-

(2)

Trade openness: We use a common indicator to represent trade openness, which is denoted by the variable open.

We calculate trade openness by dividing the city’s import and export trade volume by its GDP:

We collect the import and export trade data of various cities for 2007, 2008, 2013, and 2018 from the ⟪China Regional Economic Statistical Yearbook⟫. Since the regional statistical yearbooks do not provide a city’s import and export data before 2003, the import and export trade volumes of each city in 2002 are taken from the 2002 statistical bulletin of each city and the 2003 statistical yearbook of each province. Note that some cities such as Bengbu, Xianning, and Nanchong did not have data for 2002, and hence, the data are taken from the 2003 statistical bulletin. The total amount of exports and imports for 2002 is calculated according to the growth rate and gross amount. The unit of import and export is US$10,000. The GDP of c city for a year is taken from the China City Statistical Yearbook. The unit of GDP is 10,000 yuan. Rate denotes the average exchange rate of the city’s RMB against the US dollar for the year, taken from the China Statistical Yearbook. There may be a two-way causal relationship between labor wage levels and trade openness: On the one hand, an increase in trade openness will affect the wage level of labor, and on the other, the rate of trade opening will be faster in areas offering higher wages or experiencing a rapid wage growth. (Liu and Li, 2012; Siswana and Phiri, 2021), among others, used instrumental variables to reduce the impact of endogeneity on the estimation results. As the instrumental variable of trade openness, we choose to use the shortest distance from each province to the coastline. First, this distance is related to the degree of trade openness, and coastal areas have larger overseas markets than inland areas due to their geographical characteristics and national policies (Siswana and Phiri, 2021). This can also be attributed to the increasing gap in trade liberalization between coastal and inland regions since the opening up (Kanbur and Zhang, 2005). Second, we do not find any relationship between the shortest distance from each city to the coastline and individual wage levels. Therefore, this study selects the distance to ensure the validity and robustness of the estimation. Specifically, the data are processed according to the city’s administrative division; the shortest distance from the coastline starts from the geometric center of the city, which is expressed in kilometers and processed by the ArcGIS software. To test the robustness of the results, this study uses the relative exogenous tariff data as an instrumental variable to re-estimate trade openness.Footnote 1 The weighted tariff of each city is calculated as follows:

Where trtariffht represents the non-scale tariff of city c in year t, workercht represents the employment of industry h in city c in year t, and totalworkerct represents the employment of all the tradable industries (mining, manufacturing, agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, forestry, animal husbandry, and sideline fishery) in city c in year t. We consider the number of people in the non-tradable sector due to the following reasons: (a) it is difficult to quantify tariffs, such as services, in non-tradable sectors, and (b) under the general equilibrium framework, studies prove that the weighting of price changes in the non-tradable and tradable sectors is equal. It is more scientific to use the tradable sector to calculate the tariff than the non-tradable sector; the tariff of this sector is set to 0 (Brian, 2013). trtariffht represents the import tariffs of industry h in year t. The product tariff data are taken from the World Trade Organization’s tradetariff databaseFootnote 2, owing to the gap between the harmonized system (HS), International Standard Industrial Classification, and China’s national economic industry classification. Following Jia and Lin (2021), we perform the following matching: we obtain the HS6 product tariff data based on World Trade Organization data, convert the data to the HS2002 version through the conversion table of the United Nations Statistics DivisionFootnote 3, reconvert the HS2002 to the International Standard Industrial Classification (Rev3)Footnote 4 according to the conversion table, and finally perform simple averaging in various industries in China according to the country’s GB/T2002 correspondence tableFootnote 5.

Control variables

-

(1)

Individual characteristic variables: This variable ascertains whether the nationality is Han (han); individuals are assigned a value of 1 if they belong to the Han nationality and 0 otherwise; concerning Gender (male), men are assigned a value of 1 and women 0; Age (age) and age-squared (age2), except for the age provided directly in 2002, are rounded from the survey year to the date of birth. Health level (health) is ascertained based on the following question taken from the CHIP questionnaire: “Compared with your peers, please evaluate your current health status”; we assign a value of 1 to the responses “very good” and “good” and 0 to others. Educational level (edu) is expressed in the questionnaire as years of formal education. Concerning marital status (marriage), we assign a value of 1 to individuals in their first marriage, remarriage, or cohabitation, while divorced, widowed, and unmarried respondents are assigned 0.

-

(2)

Enterprise-level data of individuals: We use the CHIP database and industry codes to match the following variables. These data cover the ownership of the individual’s enterprise (comtype). According to the question “The type of ownership of your current unit,” the types of units are classified into state-owned enterprises and institutions, collective ownership, private enterprises, foreign-funded enterprises, and others. We assign a value of 1 to state-owned enterprises and institutions and 0 to the others. Concerning the size of an individual’s enterprise (comsize), we consider the question “How many people work in your company including you?” The values 1, 2, 3, and 4 are assigned to a workforce size of 1~100, 101~500, 501~1000, and more than 1000 people, respectively. Concerning the size of an individual’s industry (ind), the survey includes the following industries: agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fishing, mining, manufacturing, electricity, gas and water production and supply, construction, real estate, and other national economic industries. Based on our research needs, we assign a value of 1 to manufacturing and mining and 0 to the others.

-

(3)

Other variables: In addition to using the main variables of city size to show the driving force of urban population agglomeration, compensation, and selection effects, we also use an economic index of per capita GDP (pcgdp) to control for the level of urban development.

Data sources

Owing to data availability at the city and individual levels, this study selects the 2002–2018 survey data from CHIP to conduct a descriptive analysis of income, trade liberalization, and size of the sample city; it uses the 2018 CHIP data for empirical analysis and verification. The data for 2002 are added to the Chongqing municipality database after adjusting them to 1995 levels; the data cover 62 cities. We have 20,632 observation-years for data on personal living conditions in urban areas. Adjusting with 2002 as the base period, the 2007 data provide information on five provinces (municipalities)—Shanghai, Zhejiang, Fujian, Hebei, and Hunan—and include 10,000 urban households. However, the urban data from the CHIP only disclose information on 5000 urban households (14,683 family members). The family information from the National Bureau of Statistics has not been made public, and the public data sample includes only 18 cities. The 2013 survey data cover 15 provinces and 124 cities, including a sample of 7175 urban households. The 2018 survey data increased the number of cities from 144 in 2013, expanding the sample coverage to 11,506 urban households and 36,259 household members.

Since this study focuses on cities, we select the urban sub-sample database from CHIP for analysis excluding county-level cities and minority autonomous prefectures. The analysis sample includes all female workers aged 16–55 years and male workers aged 16–60 years. The official retirement ages for Chinese women and men are 55 and 60 years, respectively, which are consistent with the standard research on wage structure.

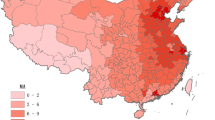

Descriptive statistics

The empirical partial regression uses the 2018 CHIP data for analysis. Keeping all variables without missing data, 13,297 effective observations were obtained. A total of 144 cities were distributed across 15 provinces—Anhui, Beijing, Chongqing, Gansu, Guangdong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Neimenggu, Shandong, Shanxi, Sichuan and Yunnan. The descriptive statistics of the main variables are given in Table 1.

Due to the presence of a large number of variables in the econometric model, the results of the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficient tests on the main variables show that the correlation coefficient between the variables does not exceed 0.8.

Basic regression and robust test

Trade liberalization, changes in annual wage premiums by city size

Before giving the basic empirical results, this article first uses the data of the CHIP urban sub-sample database in 2002, 2007, 2008, 2013, and 2018 to perform a simple OLS regression to investigate the wage income of urban laborers in China in the context of opening up to trade. The dependent variable is logarithmic monthly income, and the main variables are the degree of trade liberalization and city size (big is a large city, middle is a medium-sized city, and small cities are used as the control group, in order to further analyze the development gap of urban scale, consider the balanced distribution of samples as much as possible and reduce the deviation of empirical results, this paper based on the existing research (Zhang et al., 2021) defines a big city with a population of more than 5 million, a medium-sized city with a population between 2 million and 5 million, and a small city with a population of less than 2 million), other control variables have mentioned above, which control the ownership and industry, Company size, city, etc. The regression results are shown in Table 2.

From Table 2, it can be seen that from 2002 to 2018, the positive effect of trade liberalization on wage income growth showed a fluctuating trend. It fell from 29.3% in 2002 to 17.6% in 2007. After the economic recovery, the positive effect rose again, reaching a peak of 31.6%. This indicates that the wage growth effect of trade liberalization has a stable time pattern. We chose a period of about ten years after China’s accession to the WTO. The wage growth effect of trade liberalization also reflects the basic reality of China’s open-door strategy. In the first few years after China’s accession to the WTO, trade liberalization clearly brought about a wage premium effect, but this effect gradually weakened over time, reaching its lowest point during the global financial crisis in 2007. After 2008, with China’s economic recovery and adjustments to its open-door policy, the role of trade liberalization in wage income growth gradually increased to a higher level. Looking at the wage premium effect in large cities, it decreased from 22.0% in 2002 to 5%. Although the income of workers in large cities is still relatively high, its expansion effect has been declining year by year. Compared with small and medium-sized cities, large cities still enjoy a higher wage premium, which is consistent with China’s experience and facts.

Based on the econometric model and the basic description of the wage premium over the years, this section uses 2018 CHIP data to test the main factors affecting wage income and focuses on the impact of trade liberalization and city size and their cross-term on wage income. First, by gradually adding the cross-term, we perform a general least square and two-stage least squares estimations. After testing the robustness of the basic regression results, we further test the mechanism and analyze the impact of heterogeneity on income.

Basic regression results

Table 3 reports the results of the basic regression. Columns (1) and (2) present ordinary least squares regressions, column (2) presents the interaction between city size and trade liberalization on the basis of column (1), and columns (3) and (4) present the corresponding two-stage least squares regressions. The result shows that an increase in trade openness significantly promotes urban wage levels in China. The comparative columns (1)–(4) show that if the endogenous relationship between trade liberalization and urban size is not considered, then the model may overestimate the effect of trade liberalization on wage income and underestimate the ability of urban scale to enhance wage premium. The following section presents a detailed analysis on the basis of column (4).

First, the degree of trade liberalization has a significant effect on wage income, which is in line with the theoretical expectation of this study. In particular, owing to the continuous development in China’s economic level in recent years, we treat the import and export trade with an inclusive and open attitude. Chinese enterprises have also increased their participation in high-end production. Enterprises are gradually switching their focus—from one similar to that of the Apple Foxconn factory to one on exporting the brand. In this context, it must be noted that trade liberalization can expand the employment market, improve the overall employment level of society, facilitate talent–job matching, and increase the volume of highly skilled labor in enterprises, thereby improving the efficiency of economic operations and increasing income levels.

Second, according to the measurement results, each unit increase in trade liberalization will increase wage income by an average of 5.8%, which is significant at the 1% level. The theoretical analysis and empirical test show that the income level of workers in all cities will benefit from the expansion of the urban scale, as follows. First, a series of chain reactions brought about by the urban agglomeration economy will increase urban productivity. Second, enterprises will realize a scale economy, which is passed on to workers through the rent-sharing effect. Third, the high-wage income will maintain the attractiveness of large cities while compensating for high housing costs. Fourth, the average level of human capital will be promoted through the selection effect in larger cities and enterprises and those by skilled labor. This is also the reason many young people desire to relocate to Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou.

After considering the endogenous influence, we find a negative interaction between city size and trade liberalization, significant at the 1% level. This shows that the larger the city, the weaker the effect of trade liberalization on an increase in wage income; in other words, the effect of city size on the income level will decrease with the deepening of trade liberalization. This shows that China’s urban and rural labor employment positions and skill-matching are yet to mature; it is also critical for the surplus rural labor to acquire comprehensive training to improve their skills to be integrated with the city’s core workforce. Additionally, cities must be vigilant of the low demand elasticity caused by high housing prices.

The conclusion here is similar to that of the literature on other factors affecting wage income. The relationship between age and wage income follows an inverted U-shaped curve, in line with the life-cycle hypothesis of consumer behavior as well as the current situation—workers tend to earn more income and consume when they are young, and their income decreases in old age. Men’s wage income is generally higher than that of women. Several studies attribute the gender wage gap to the wage theory. In general, men’s marginal output is higher than that of women. In China, recruiting women also increases enterprise costs as it covers childbearing and retirement costs, among others. Institutional economics presupposes that men are more productive than women in the workplace, which results in men having higher bargaining power (Lansbury, 1994; Kuhn and Villeval, 2015). Furthermore, the higher the educational qualification, the higher the wage income (Li and Chu, 2022). Based on the model, the estimated return on education is about 5%; while it is close to the 2–5% education return rate obtained by Chen and Hamori (2009), it is much lower than the world average of 10.1% and the Asian average of 9.6% (Psacharopoulos, 1994). This shows that although the state has always attached great importance to education, much progress remains to be achieved. Cities should also focus on vocational education and skills training and strive to eliminate the institutional barriers between education and employment; this will enhance the significance of the concept of “knowledge is wealth.” The health level has a positive incentive effect on wage income, and the healthier the people, the more likely they are to engage in jobs with high returns. The effect of marriage on the increase in wage income is significant at the level of 1%, which is related to the long-term plan of Chinese family consumption expenditure and reserve investment. The existence of marriage premium conforms to Chinese social norms. Concerning ownership type, employees who work in state-owned enterprises or institutions get a higher wage premium. The profit level of some enterprises (Juha et al., 2009) and the low gender discrimination in the state-owned sector can contribute toward the fair absorption of different employment groups.

Robustness check

This study uses different methods to verify the robustness of the previous empirical results. The results are shown in Table 4.

First, robustness test 1 uses the import penetration rate instead of trade dependence to measure the degree of trade openness; the calculation method is as follows:

The data are taken from ⟪China Urban Statistical Yearbook⟫ and ⟪China Statistical Yearbook⟫. The results show that the wage income level will increase by 0.034 units for each unit increase in city size. Although there is a small difference between the marginal effect and the basic regression, the effect of city size and trade liberalization on the income level remains significantly positive and the cross-item is significantly negative. The analysis has no effect on the previous results.

Second, this study changes the instrumental variable of trade openness to urban non-scale tariffs to replace the reciprocal of the shortest distance to the coastline. The regression results are similar to those of the basic regression. To further verify robustness, we reduce the extreme value of 5% from the beginning to the end of the sample and repeat the above series of analyses to reduce the impact of the extreme value on the sample. Based on CHIP data availability, we calculate the hourly wage income. To eliminate the influence of labor supply, this study uses hourly wage income to replace monthly income. According to the regression results of the last column in Table 4, the marginal effect of urban size and wage income is about 0.033, and there has been no change in the degree of trade liberalization and the signs and significance of the cross-items. The above analysis proves the robustness of the key variables of the basic regression.

Transmission mechanism and analysis of the heterogeneity sample

Test of conduction mechanism

To quantify the directional description of the above theoretical mechanism, this study conducts cross-item tests on trade liberalization, labor skills, and industrial agglomeration level. The skill level is represented by workers’ number of years of formal education, and the level of urban industrial agglomeration is represented by specialized agglomeration and diversified agglomeration; we also ascertain whether the workers are skilled workers or knowledge-based practitionersFootnote 6, respectively.

The level of industrial agglomerationFootnote 7—the specialized agglomeration (spect)—is expressed by the regional entropy:

Equation (5) represents the industrial agglomeration degree of industry lqkt, which is expressed by the location entropy, xhc represents the employed population of industry h in city c, xc represents the total employment in city c, xh represents the total employment in the industry. h in the country, and x is the total employment in the country, all of which denote the population size of the municipal districts. Diversification agglomeration is expressed by the reciprocal of the Herfindahl–Hirschman index (divct) where

In other words,

Therefore, the larger the value, the higher the degree of diversification, according to Jacobs’ externality. Table 5 shows that the coefficients of the cross-terms are all positive and significant at 1%. No matter from the perspective of technical talents or years of education, the empirical result of the interaction of technical talents and trade liberalization on wage premium is positive, indicating that the higher the degree of trade liberalization, the corresponding increase in the number of technical talents and years of education, so as to improve wage premium. For every 1% increase in the interaction of trade liberalization and technical talents, the level of wage income will increase by 0.51, while under the same conditions, the year of education has little impact on wage income; Similarly, the results of the interaction of trade liberalization and professional agglomeration or diversified agglomeration show that the deepening of trade liberalization can improve the effect of wage premium through the enhancement of industrial agglomeration, and the impact on wage income is more than 0.2.

Further analysis

From the literature review above and theoretical analysis, we can see that the impact of trade liberalization and urban size on wage income may be heterogeneous for different individuals, enterprises, or regions. To quantify this mechanism, we perform a series of grouping regressions to examine whether there are differences in wage income among different individuals, enterprises, or regions, as well as the reasons for these differences. Specifically, we conduct a macro-regional analysis due to the different transmission results of trade liberalization in the eastern and western regions and among the middle-income groups. According to national unified standards, Beijing and its provinces—Liaoning, Jiangsu, Shandong, and Guangdong—are located in the eastern region; Shanxi, Anhui, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan in the central region; and Chongqing, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan in the western region. We also conduct a group regression analysis for different types of enterprises, distinguished by ownership type and industry. Finally, the above analysis focuses on the overall focus on the overall income level; to further explore whether each influence factor exerts different effects on low, medium, and high-wage income levels, we conduct a quantile regression analysis.

Regional regression

From Table 6, it can be seen that only trade liberalization and urban expansion in the eastern and central regions can significantly increase wage income. Although the sign of the coefficient does not change in the western region, it is not significant. The development of cities is related to the free flow and allocation of various production factors. Compared with the western region, the eastern and central regions have higher levels of marketization and trade openness. Therefore, the income-promoting effects of urban agglomeration economy and trade liberalization are easier to achieve, and all are significant at the 1% level.

The Western region is relatively backward and cannot enjoy the benefits brought by policy reforms. The government supports the development of the Western region by creating employment opportunities and launching the Western Development Policy. However, the economic development of this region started relatively late. Although it has certain comparative advantages in terms of resources and factor costs, it has limited benefits because of a shortage of highly skilled labor and the inability to retain high-quality talents. Nevertheless, the development of foreign trade in the western region still unilaterally highlights the comparative advantage of tangible resources. Resource and labor-intensive products have become the main export commodities, which not only cause environmental damage but also impact the region’s openness to the outside world and the sustainable development of its economy and society. Since primary products belong to labor-intensive products, they cannot improve economic efficiency and workers’ income.

Therefore, the Western region should make reasonable use of the opportunities brought by trade liberalization, give play to its advantages, develop supporting industries and sustainable development industries, and introduce high-tech products that qualify for national preferential policies. To promote the overall industrial development of the region, it is necessary to solve current problems while strengthening its own competitive advantages and focusing on the integrated development of culture, environment, and industrial approaches.

Regression of enterprises

The deepening of the degree of trade liberalization is manifested through the reduction of tariffs on imports of final products; this reduces the degree of domestic protection for enterprises, contracts their market share, affects the play of economies of scale, increases production or sales costs, and reduces their sales revenue. This reduces a company’s ability to pay wages. However, according to the previous analysis, trade liberalization has brought fierce market competition and technological innovation. Domestic companies improve their management models and optimize the structure of laborers, thereby producing a forced effect. Based on a quantitative analysis, Masha (2018) also confirmed that when productivity reaches a certain level, the counterforce effect of trade liberalization will be greater than the squeeze on corporate income.

Table 7 provides the results of enterprises distinguished by ownership (state-owned or non-state-owned) and industry (manufacturing or non-manufacturing). In terms of the wage premium effect, the urban-scale wage premium effect is significant for both state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises, as well as for laborers in the service industry. However, it has no significant effect on the wage income of workers in the manufacturing industry. In this study, there were approximately 2375 samples in the manufacturing industry, while the remaining samples were mainly from the tertiary industry. Although China is a manufacturing powerhouse, it is striving to transition from “Made in China” to “Created in China.” In this era of information, high-paying industries such as computer information, finance, and information technology require high levels of skills from talents. This group often possesses high intelligence and strong initiative, and they can absorb richer knowledge from both domestic and international sources and produce high-value-added results. China also attaches importance to the opening up of the tertiary industry, which is in line with the need for reform and opening up and plays an important role in improving the overall income level of the population.

Quantile regression of different income groups

Table 8 presents the regression results of trade liberalization and urban scale for different income levels. From the regression coefficients, it can be observed that both the urban scale wage premium and trade liberalization have significant positive effects on different income groups. This implies that workers at different income levels can increase their wage income by participating in international trade. This is because when high levels of foreign direct investment or foreign investment are introduced, companies can achieve higher profit levels and pass them back to employees through technology spillover effects and human capital accumulation. Furthermore, through cross-sectional comparisons, it can be noticed that trade liberalization has a relatively larger impact on middle- to low-income groups compared to high-income groups.

Conclusions and implications

China’s urbanization has led to the emergence of a wage premium effect in urban areas. This study uses micro-data from the China Household Income Project and matching data from 144 cities to quantitatively analyze the impact of globalization and urbanization on Chinese workers’ incomes. We find that, first, trade liberalization has a significant positive effect on wage income for urban residents, especially in the early years after China’s accession to the WTO. However, then this effect may fluctuate over time. Specifically, from 2002 to 2018, the impact of trade openness on wage income is generally positive, declining from 29.3% in 2002 to 17.6% in 2007, then rising to 31.6% in 2008, and subsequently decreasing slightly. Initially, trade liberalization brought about a wage premium effect, but over time, this effect gradually weakened, reaching its lowest point during the global financial crisis in 2007. After 2008, with the economic recovery and adjustments to China’s opening-up policies, the role of trade liberalization in driving wage growth gradually increased to a higher level. Under the backdrop of rapid trade liberalization and urbanization, the urban scale can increase labor wage income, but it does not amplify the wage premium effect of trade liberalization. On the contrary, the larger the city, the weaker the impact of trade liberalization on wage income growth. This result may seem unexpected at first glance, but it may reflect some issues in China’s urban development, such as a low degree of labor marketization and high housing prices in large cities. Secondly, the study conducts heterogeneity tests based on regional groups, enterprise categories, and labor force groups. The results show that compared to the Western region, trade liberalization in the eastern and central regions of China can generate significant wage premium effects. The wage promotion effect of trade liberalization is more pronounced in the service industry than in the manufacturing industry, and it is greater for the middle and low-income groups than for the high-income groups, which helps narrow the income gap between different groups. Finally, trade liberalization in Chinese cities generates a wage premium effect through mechanisms such as upgrading worker skills, expanding urban scale, and strengthening industrial agglomeration.

These findings have important policy implications for improving income distribution through labor market liberalization. They indicate the significance of comprehensive openness and a new pattern of urbanization in China. The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China also emphasizes the importance of prioritizing people’s interests and ensuring that the people share the benefits of reform and opening up. It emphasizes fair distribution and promoting common prosperity. However, China should focus on certain areas to reap the benefits of trade liberalization. First, considering the crucial role of trade liberalization in raising workers’ wages, China should further accelerate this process. Second, China should encourage the development of medium and small cities and promote a more inclusive attitude towards the non-resident population in large cities. These cities should be encouraged to help mobile populations achieve true citizenship. The government should also foster a multi-centered and complementary urban network system in China. Third, China should aim for regional coordinated development, especially in the Western region. This not only benefits the development of more advanced regions leading other areas but also helps underdeveloped regions nurture their own comparative advantages. Finally, to maintain the vitality of non-state-owned enterprises, the government should accelerate the market-oriented reform of the state-owned enterprise system and emphasize the role of the “invisible hand” to encourage manufacturing enterprises to participate in high-end production of the global value chain.

Data availability

The original data for this study was obtained from the Beijing Normal University Chinese Household Income Survey (CHIP) Database, downloaded from http://www.ciidbnu.org/chip/index.asp.

Notes

See the calculation methods of Rafael and Brian (2019).

Since this study focuses on the urban economy, the industry tariff excludes the primary industry, which is consistent with the industry segmentation criteria of Sheng (2002; 36 industry segmentations).

In CHIP 2018, high-tech workers comprise personnel with senior professional titles, intermediate titles, and junior titles; those at the technician level, bureau level, or above; and those in department/section-level cadre, section members, and enterprise senior and middle-level management; they are assigned the value 1, and others are assigned 0.

Regarding employment in a city’s industry, we only have data pertaining to Chongqing and the leasing industry. Hence, the data from leasing companies in all cities are used to represent the leasing industry in the districts and cities of Chongqing.

References

Brian KK (2013) Regional effects of trade reform: what is the correct measure of liberalization? Am Econ Rev 103(5):1960–1976

Chen G, Hamori S (2009) Economic returns to schooling in urban China: OLS and instrumental variables approach. China Econ Rev 20(2):143–152

Chen H, Chen JW, Yu WC (2017) Influence factors on gender wage gap: evidences from Chinese household income project survey. Forum Soc Econ 46:371–395

Chen S, Luo EG, Alita L, Han X, Nie FY (2021) Impacts of formal credit on rural household income: evidence from deprived areas in western China. J Integr Agri 20(4):927–942

Combes PP, Duranton G, Gobillon L, Puga D, Roux S (2012) The productivity advantages of large cities: distinguishing agglomeration from firm selection. Econometrica 80(6):2543–2594

Daiki K (2019) Does high labor mobility always promote trade liberalization? Can J Econ 52(3):21–42

Glaeser LE, Resseger GM (2010) The complementarity between cities and skills. J RegionSci 50(1):221–244

Ian S (2006) Trade liberalization: welfare distribution and costs discussion. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 28(3):426–428

Jia XY, Lin S (2021) A factor market distortion research based on enterprise innovation efficiency of economic kinetic energy conversion. Sustain Energy Technol Assess 44(1):101–121

Juha V, Daria P, Rajesh KP (2009) Internationalization and company performance: a study of emerging Russian multinationals. Multinatl Bus Rev 17(2):157–178

Kanbur R, Zhang XB (2005) Fifty years of regional inequality in China: a journey through central planning, reform and openness. Rev Dev Econ 9(1):87–106

Krisztina KK, Robert S (2015) Poverty, labor markets and trade liberalization in Indonesia. J Dev Econ 117:94–106

Kuhn P, Villeval MC (2015) Are women more attracted to cooperation than men? Econ J 125(582):115–140

Lansbury RD (1994) The workforce of the future: implications for industrial relations, education and training. Econ Labour Relat Rev 50(1):33–36

Li HY, Shao M (2017) City size, skill difference and laborer’s wage income. Manag World 8:36–51. (in Chinese)

Li, S (2017) Real estate wealth effect of Chinese households: an empirical study based on micro survey data. Proceedings of 2017 2nd International Conference on Economics and Management Innovations (ICEMI), 399-404

Li Z, Chu YJ (2022) Is hierarchical education investment synergistic? Evidence from China’s investment in general and advanced education. J Knowl Econ 14(2):1522–1537

Liu B, Li L (2012) Trade openness and gender pay gap. China Econ Q 11(2):429–460. (in Chinese)

Lu M, Zhang H, Liang WQ (2015) How land supply in favor of the Midwest has pushed up wages in the East. Soc Sci China 5:59–83. (in Chinese)

Magnac T, Roux S (2021) Heterogeneity and wage inequalities over the life cycle. Eur Econ Rev 134(2):103–115

Marjit S, Acharyya R (2006) Trade liberalization, skill-linked intermediate production and the two-sided wage gap. J Econ Policy Reform 9(3):203–217

Masha B (2018) Does trade liberalization narrow the gender wage gap? The role of sectoral mobility. Eur Econ Rev 109:305–333

Michael O, Pascal N, Isaac NN, Isaac K (2021) Dynamic capabilities and enterprise growth: the mediating effect of networking. World J Entrep Manag Sustain Dev 17(1):1–15

Muthukumara M, Gopalakrishnan BN, Wadhwa D (2020) Regional integration in South Asia: Implications for green growth, female labor force participation, and the gender wage gap. The World Bank

Ni NN, Liu YL (2019) Financial liberalization and income inequality: a meta-analysis based on cross-country studies. China Econ Rev 56:101306

Pablo L, Luciana V, Gustavo Y (2022) Cognitive and socioemotional skills and wages: the role of latent abilities on the gender wage gap in Peru. Rev Econ Househ 20:471–496

Psacharopoulos G (1994) Returns to investment in education: a global update. World Dev 22(9):1325–1343

Qi L, Xi L (2023) Unveiling the trade and welfare effects of regional services trade agreements: a structural gravity approach. Econ Model 127:106426

Rafael DC, Brian KK (2019) Margins of labor market adjustment to trade. J Int Econ 117:125–142

Rodríguez-Castelán C, López-Calva LF, Lustig N et al. (2022) Wage inequality in the developing world: evidence from Latin America. Rev Dev Econ 26(4):1944–1970

Rubiana C, Sharma GJ (2011) Industrial de-licensing, trade liberalization, and skill upgrading in India. J Dev Econ 96(2):314–336

Serrano R, Pinilla V (2014) Changes in the structure of world trade in the agri-food industry: the impact of the home market effect and regional liberalization from a long-term perspective. Agribusiness 2:1963–2010

Sheng B (2002) An empirical analysis of the political economy of China’s industrial trade protection structure. China Econ Q 2:603–624. (in Chinese)

Siswana S, Phiri A (2021) Is export diversification or export specialization responsible for economic growth in BRICS countries? Int Trade J 3:243–261

Sunge R, Ngepah N (2020) The impact of agricultural trade liberalization on agricultural total factor productivity growth in Africa. Int Econ J 4:571–598

Tan R, Wang RY, Heerink N (2020) Liberalizing rural-to-urban construction land transfers in China: distribution effects. China Econ Rev 60:101147

Thomas K, Michael S (2012) The sources of urban development: wage, housing, and amenity gaps across American cities. J Region Sci 52(1):85–108

Thurlow J (2007) Trade liberalization and pro-poor growth in South Africa. Stud Econ Econ 31(2):161–179

Xie XZ, Huang HW (2020) Influencing factors in regional income gap in Guangdong. J Phys Conf Ser 1622(1):12–32

Zhang M, Zhang GG, Liu HY (2021) Analysis of the impact of tourism development on the urban-rural income gap: evidence from 248 prefecture-level cities in China. Asia Pac J Tour Res 26(6):614–625

Zhang P, Liu Y, Miao L (2021) Impacts of social networks on floating population wages under different marketization levels: empirical analysis of China’s 2016 national floating population dynamic monitoring data. Appl Econ 53(22):2567–2583

Zhao LQ, Wang F, Zhao Z (2020) Trade liberalization and child labor. China Econ Rev 65:101575. 2021

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the General Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China “Research on Industrial Coupling, Livelihood Improvement and Promotion of Urbanization with County Cities as Important Carriers” [grant numbers 21BJY136].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WZ: conceptualization, supervision, validation, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. JW: conceptualization, supervision, validation, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. XO: conceptualization, supervision, validation, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

This work did not include any studies with human or animal participants conducted by all the authors.

Informed consent

This work did not include any studies with human or animal participants conducted by all the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Wang, J. & Ou, X. Trade liberalization, city size, and urban wage premium: evidence from China’s city and individual micro-data. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02681-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02681-7

- Springer Nature Limited