Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance due to the irrational and non-sustainable use of antimicrobials poses a serious threat to animal health, human health and urban food security. This study aimed to access the knowledge and perceptions of dairy farmers regarding antimicrobial use and misuse in Lahore, Pakistan. This is the first study regarding antibiotic misuse in Lahore, Pakistan. A random sample of 270 dairy farmers from urban and suburban areas of Lahore participated in an interview-based survey conducted in 2019–20. The results were analyzed using SPSS version 16. About 22% of farmers do not consult a veterinarian, 32.9% do not follow correct dosage instructions and 39% discontinue treatment once the disease signs subside. Moreover, 40% of farmers were unaware of the dangers of misusing antibiotics and admitted to saving leftover antibiotics for future use. Alarmingly, over 20.7% of respondents share antibiotics with friends/farmers and 43% sought advice from non-veterinarian sources. Furthermore, 90% of farmers perceived self-medication as more economical than consulting a veterinarian. Dairy farmers have a wrong perception of antibiotic efficacy, use, expertise of veterinarians and cost of antibiotics. The absence of a food policy and lack of antibiotic use guidance is a serious gap in Pakistan. Antibiotic dispensing laws need to be developed and strictly implemented. Awareness campaigns need to be launched so that farmers get knowledge regarding the uses, overuse and misuse of antibiotics. A holistic approach is essential to address the potential food security crisis caused by non-sustainable farming practices. Policymakers must take action to bridge the gap in the Pakistani food supply chain and promote the sustainable use of antimicrobials/antibiotics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

‘Food security’ is defined by FAO as: “the availability at all times of adequate, nourishing, diverse, balanced and moderate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices” (FAO 2003). The concept of food security is based on four dimensions: (1) the availability of food, which is linked with supply chain activities; (2) the utilization of food, which is linked with safety and nutritional value; (3) access to food, this linked with economic and social affordability; (4) stability of food, this linked to resilience of food system (Smith and Floro 2020). In Pakistan, 2nd point of food security i.e. safety and nutrition is not much discussed/emphasized. Generally the public is more concerned about the quantity of food (point 1) and for them, quality is the secondary issue. The same scenario is also applicable to the dairy industry in Pakistan. The use of uncontrolled antimicrobials/antibiotics in dairy farms is quite prevalent, and it is creating food security and non-sustainability issues (Hasnain 2020). Von Boeckela et al. (2015) recommended the call for action to improve antibiotic efficacy and simultaneously safeguard food security in lower-middle and low-income countries.

Antimicrobials are widely used for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, but some are also used as supplements to stimulate growth in livestock (Carvalho and Santos 2016). They are generally considered pseudo-persistent compounds due to their constant input and consistent presence in the environment (Boeckel 2018). The discovery of penicillin (in 1928) unleashed the era of antibiotic development and innovation. Antimicrobials are not only used for the treatment of diseases in humans but are also being used widely in aquaculture and animal husbandry (Kalunke et al. 2018). Major sources of antibiotics in our ecosystem include sewage effluents, aquaculture production, agricultural runoff, and veterinary drug usage (Biel-Maeso et al. 2018; Pan and Chu 2017). Their presence in the environment becomes problematic when antibiotic resistance is developed among microbes due to excessive use (Martínez et al. 2015). In a developing world, antibiotics are among the most commonly used/purchased drugs, due to the prevalence of infectious diseases. Overuse of antibiotics significantly influences therapeutic practices, economic state, and physical well-being of the general public (Gebeyehu et al. 2015).

Pressure from farmers (end-users of antibiotics) strongly influences the prescription behavior of veterinarians (McDougall et al. 2017). The unwillingness of farmers to stick to veterinarians’ advice leads to increased antibacterial use. Therefore, veterinarians must adopt a less directive and more mutual approach to deal with farmers for better antimicrobial practices. Educating farmers about antimicrobial dangers and setting the limit of antimicrobial residue for food products is the need of the hour, to combat the problem (Bard et al. 2017).

The effectiveness of the “rational use of antibiotics by farmers” pivots on its capability to simultaneously engage all the stakeholders, including farmers, peers, veterinarians, medicine companies, marketing companies, drug inspectors, and policymakers. If any of these groups are left disengaged, the rational use of antibiotics is compromised. Farmers’ knowledge and perception regarding antibiotic use and misuse are very critical in rational use. To promote this rational use, a successful plan must be able to compel farmers, like through awareness and veterinarian advice. It should also restructure public policy with more emphasis on updating the knowledge of farmers and changing their attitudes. The theory of change outlined here seeks to combat antimicrobial resistance in Lahore’s dairy farming sector by addressing knowledge gaps among farmers. This may be achieved by implementing policies, and regulations, promoting sustainable farming practices and through awareness campaigns. This multifaceted approach aims to mitigate the risks associated with the irrational use of antimicrobials and ensure a more secure food supply chain. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the theory of change behind the dairy farmer’s awareness level and the role of stakeholders (Reddy 2018).

The majority of published studies on self-medication and antibiotic resistance are focused on hospitals (Giannitsioti et al. 2016), universities (Ayepola et al. 2018), and communities (Yusef et al. 2018). Very little has been investigated to evaluate the practices on dairy farms, especially from farmers’ perspectives. This is the first study concerning the knowledge and perception of dairy farmers regarding antibiotic misuse in Lahore, Pakistan. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of dairy farm owners about antibiotic use and resulting resistance among farm animals.

Data and methodology

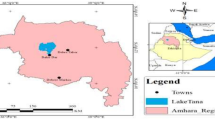

Lahore is the capital of the province of Punjab in Pakistan and was selected as the study area. Different locations were randomly selected in urban and sub-urban areas of Lahore for the survey (Fig. 2). Farms were selected on the following basis (i) where the animal number is more than 15, (ii) the farm area is small/congested, (iii) reported high disease burden and (iv) where antibiotics are in frequent use. Farmers were interviewed (conducted in 2019–20) using a comprehensive and well-structured interview to assess the knowledge, attitude and perceptions of dairy farmers related to antibiotic resistance among farm animals. Respondents were informed about the purpose of the survey and confidentiality of their information was ensured. The study did not violate any moral or ethical obligation.

Sample size

In total two hundred and eighty-five dairy farmers were included in the current study. The exact number of dairy farms and dairy farmers is not reported anywhere, so getting the exact population size is not possible. The Punjab Statistical Bureau in “Punjab Development Statistics 2019” did not report the number of dairy farms (Punjab Development Statistics 2021). As this is the first and initial study of its kind, only 285 dairy farms showed their willingness to participate. Two hundred and seventy interviews were completed out of a total of two hundred and eighty-five. Over 94.73% of interviews were included and the rest (5.27%) were excluded from the study due to their non-compliance with key variables of this research. A pilot study was conducted with randomly selected dairy farmers before the detailed survey which aimed to check the feasibility of the present research. All interviews were conducted at the respondent’s place of work.

Interview

The interview was conducted by using a structured questionnaire, which was prepared after a profound discussion with experts, and faculty members and an analysis of related questionnaires/interviews (Kramer et al. 2017). It was further modified to make it suitable as per study requirements. The interview responses were verified for reliability and internal consistency by calculating Cronbach’s alpha using the method described by Cronbach (1951). The study was conducted in 2019. The interview consisted of mainly two parts and eighteen questions. Questions related to the demographic characteristics of the studied population were gathered in the first section. There were five questions including age, education level, place of living, income per animal per day and the number of household members. The second part of the interview was designed to get information on the knowledge, attitudes and perspectives of farmers about antibiotic use and resistance. The first question was related to the frequency of sickness which helps identify a disease burden and consumption of antibiotics in animals. The second question was to assess the preference of farmers in using antibiotics over usual home remedies. The next two questions were about the trend of consultation with veterinarians and farmers’ satisfaction level with the prescribed medication. Information regarding antibiotic protocol was gathered in further questions i.e. focus on correct dosage instructions, discontinuity of therapy after the decrease in the signs/symptoms and management of leftover antibiotics. We assessed the prevalence of antibiotic resistance by determining whether the same antibiotic protocol always works whenever animals are treated for a specific disease. Subsequent questions were related to considering non-veterinary advice in using antibiotics. We evaluated farmers’ awareness regarding the dangers of misusing antibiotics by discussing prominent issues such as the appearance of side effects, the requirement for more time to subside signs/symptoms, and the inconsistency of the same treatment always working. The last question was about the cost-effectiveness of using antibiotics where a two-point scale (Yes or No) was used to record the responses of interviewed farmers.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained after a prudent interview was analyzed using SPSS version 16 (Statistics Data Editor 16.0). Descriptive statistics was applied to calculate frequencies and percentages. Descriptive measures were used to condense the detailed data related to the perceptions and attitudes of farm owners. Bar graphs were constructed for comparative analysis of different variables.

Results

Demographic information

All participants in this study were male. The highest number of respondents were from the age group 31–40 (41.9%) and the lowest number of respondents belonged to the age group 61–70 (2.6%). The numbers of respondents in the age group 20–30 were 14.1%, 41–50 were 27%, and 51–60 were 14.4%. The majority of the participants were illiterate or less educated: 23.3% of respondents were illiterate, 24.4% were under matriculation (in Pakistan Matriculation is equivalent to O-level education) and 25.6% just had a matriculation certificate; therefore, verbal assistance was required to complete the interview. The education level of 20.4% of participants was intermediate. Very few respondents (4.1%) had graduate degrees, and even fewer (2.2%) were up to the level of masters. Most of the interviews (58.1%) were completed in peripheral sub-urban areas of Lahore and others (41.9%) were completed in urban areas of Lahore. Maximum participants (43.0%) reported an income of 400–500PKR per day (1.9–2.4US$) and the majority (51.5%) had 8–10 family members (Table 1). Data regarding farm description is given in Table 2.

Disease burden

Information about the frequency of sickness in animals is necessary to identify the probability of antibiotic consumption. According to the data collected from the current study, about 31.1% of respondents reported that their animals got sick three times during the last year (Table 1). Farmers whose animals got sick only once were 24.8%, twice were 23.7% and 20.4% reported that their animals got sick more than three times within the last year.

Antibiotic leftovers

According to current research, most of the participants reported that they threw their left-over antibiotics in dustbins 41.9% and 2.2% flushed it or threw it in some canal/water body (Table 1). Saving of antibiotics for future use is also high (35.2%) and some said that they share their antibiotics with friends and other farm owners (20.7%).

Perceived danger

Awareness of the general public can be judged by asking them about their knowledge related to the dangers of misusing antibiotics (Kramer et al. 2017). In the present study, 40% of farmers are not aware of the dangers of misusing antibiotics (Table 1). Seventy-nine (29.3%) farmers stated that side effects do appear, 17% answered that the same antibiotic treatment does not work and 13.7% considered that frequent use of antibiotics increases the time of disease recovery.

Perception and knowledge of the farmers

Farmers still prefer to apply home remedies whenever they face some sort of illness rather than referring them to a professional veterinarian (Table 3). Upon asking about the efficiency of antibiotics over usual home remedies, most people reported that they think antibiotics work more efficiently 63.7%, while some farmers (36.3%) preferred home remedies over antibiotics. The majority (78.5%) responded positively towards consultation with a veterinarian. Almost the same status was observed when farmers were asked about their satisfaction level with veterinarians. Farmers (68.1%) reported that they follow correct dosage instructions as prescribed by veterinarians and a bit less (61.5%) confided that they discontinue treatment once signs/symptoms of the disease subside. Farmers (54.8%) stated that the same antibiotic doesn’t work always whenever animals are treated for a specific disease. This was helpful to evaluate the knowledge of farmers and information about antibiotic resistance. Most (43.3%) agreed that they use antibiotics recommended by non-veterinary advisors and 36.3% said that they have recommended antibiotics to their friends and other farmers based on their own experience. Mostly, farmers claimed that they are well aware of the dangers of misusing antibiotics (60%). A significant majority of farmers (90.4%) declared that it is not economically viable to visit a veterinarian or to use a complete dose of antibiotics.

Comparative analysis of variables

An indirect relationship was observed between the educational level of farmers and their antibiotics-sharing perception. A negative correlation exists (p = −0.8) between the “use of integrated disease management and overcrowding of animals”. Similarly, there is a negative correlation (p = −0.42) between “education level and location of residency” (Table 4). Analysis of variance revealed the significant linkage (p = 0.96) between “how many times did your animal get sick last year and the area of the farm”. Likewise, a positive significant linkage is there (0.99) between “What are the dangers of misusing and location of residency” Table 5. The descending trend was as follows; illiterate (33.9%) > under matric (26.8%) > matric (26.8%) > intermediate (10.7%). The majority of the illiterate farmers were unaware of the dangers of misusing antibiotics (36.1%), compared to the farmers having elementary (26.9%) and secondary education (27.8%) (Fig. 3). The majority of the farmers having higher secondary education (47.8%) reported the same side effect of misusing antibiotics which was that the treatment protocol doesn’t seem to work always. Twenty- seven per cent answered that the same antibiotic/product may no longer be effective and take more time to cure/heal the same disease after excessive use (Fig. 4). Most of the interviews were completed in peripheral suburban areas of Lahore (58.2%). These farmers stated that their animals suffered from some sort of illness (51.1%) only once during the last year. While, among farmers living in urban areas, 26.9% reported once a year of illness for their animals (Fig. 5). The disease burden of animals (more than three times) was higher among farmers in urban areas (56.4%) as compared to suburban areas (43.6%). Farmers who claim that they throw left-over antibiotics in dustbins were 46% in urban areas and in suburban areas they were 54% (Fig. 6). The trend of sharing antibiotics with other friends was mostly seen among farmers in suburban areas (75%). Very little difference was observed in the practice of saving left-over antibiotics for future use among the farmers of urban (47.4%) and suburban areas (52.6%). The majority of the suburban farmers (74.1%) stated that they were not aware of the dangers of misusing antibiotics while the urban farmers who said so were 25.9%. Almost both urban (48.6%) and suburban farmers (51.4%) agreed likewise that it takes more time for signs/symptoms to subside after utilizing the excess antibiotics (Fig. 7).

Discussion

This is the first study in Lahore (the capital of the province of Punjab, Pakistan) to assess food security issues related to dairy farms in Pakistan. Studies suggest that the knowledge, attitude and perception of dairy farmers related to antimicrobial misuse are directly linked to the food security issue and the non-sustainability issue (Hasnain 2020; FAO 2003). Self-medication is very prevalent in farmers due to financial constraints and peer pressure. According to current research, 21% of the respondents stated that they do not consult veterinarians, which means that they follow self-medication. Analogous results were obtained in a local study in Karachi where 23% of the respondents stated that they use antibiotics without consulting a doctor (Qamar et al. 2015). In Saudi Arabia, 34% of farmers do not consulting veterinarians (Alghadeer et al. 2018). In our study, one-third of respondents (36.3%) claimed that usual home remedies work more efficiently than antibiotics. This might be a major reason explaining why farmers don’t prefer to consult veterinarians. In an Indian study, the advice of para-veterinarians and untrained ‘animal health workers’ are more taken as they charge lower fees (Mutua et al. 2020). This study also highlights that there is mistrust among farmers and veterinarians. Farmers usually believe that veterinarians safeguard the interests of medicine companies, not theirs. Big companies influence veterinarians in their prescription habits. This is the reason why farmers prefer peer advice and experience regarding antibiotic use. In this study, respondents who stated that they recommended antibiotics to their friends or other farm owners based on their own experience were 36.3%. Another parallel study was performed in Saudi Arabia where 26.8% of the respondents reported that they suggest antibiotics to others (Alghadeer et al. 2018). Friend’s advice was also found to be an important contributing factor towards self-prescription with antibiotics, in a survey conducted in Riyadh city, KSA (Al-Rasheed et al. 2016). Use of antibiotics on the suggestion of non-veterinary advisors may prove to be harmful to animals, as excessive misuse of antimicrobials leads towards antibiotic resistance.

Lack of formal education and awareness programs leads to a poor understanding of farmers. They are not very clear about the use, misuse, optimum dose, types, limitations, etc, of antimicrobials. This knowledge gap leads to wrong practices. Most of the respondents of the present study (40%) reported that they do not have any idea about the harmful side effects of misusing antibiotics. These research findings are in line with a local survey conducted in Karachi, where 41% of the respondents said that they are not very well aware of the dangers of improper use of antibiotics (Qamar and Ayub 2015). Another study was found to have similar results where 17% of respondents claimed to have not enough knowledge related to the disadvantages of excessive antimicrobial usage (Redding 2019). In Nigeria, some university students shared their views in a survey related to their knowledge and awareness regarding antibiotics. One-fourth of them responded that antibiotics might not have harmful effects on farm animals (Ayepola et al. 2018).

While considering the current research, farmers do not have much knowledge and awareness about antibiotic usage and its possible drawbacks. Therefore, a comprehensive awareness program is required to enhance the knowledge of local farmers. In this survey, most of the participants reported that they throw their leftover antibiotics in dustbins (41.9%), and others (52.2%) save them for future use. The same practice of saving antibiotics was witnessed among the general public of Saudi Arabia where almost 44.7% of participants reported saving leftover medicines from their incomplete course for future use (El-Zowalaty et al. 2016). Even a high percentage of respondents (60%) claimed to save antibiotics for future needs in China (Ye et al. 2017). About one-third of participants (56.9%) in the Nigerian survey confessed that they saved their leftover antibiotics (Ayepola et al. 2018). The practice of saving antibiotics for future use or sharing medicines between farmers indicates the prevailing risk of self-medication among them. Chauhan et al. (2018) reported that the new generation is self-relying to manage animal disease on their own, using combinations of traditional knowledge and modern medicines.

Completion of the correct dose and for the correct duration of time is not very common. This is also linked to poor knowledge and bad attitude. Farmers also see it non-economical to continue using antimicrobials for the period prescribed, even when clinical signs begin to subside. More than one-third of the farmers (68.1%) stated that they do not follow correct dosage instructions as prescribed by veterinarians and 61.5% used to discontinue the course of treatment once signs/symptoms of the disease subside. Antibiotic usage habits among the Jordanian population were assessed through a survey. Thirty-two percent of the respondents replied that they never followed the complete course of treatment as prescribed by their doctor (Ye et al. 2017). In Northwest Nigeria, just 14.8% of students replied that they discontinue using antibiotics once signs/symptoms of the disease subside. A Similar trend was observed among community members where 16% of respondents said that they did not complete their medical course duration as suggested by a doctor (Ajibola et al. 2018). In another case study, students of a Chinese University (47.9%) reported that one should immediately stop using antibiotics once symptoms of the disease disappear (Wang et al. 2017). Failure to comply with the drug withdrawal period is also very prevalent in Indian farmers and they even keep selling/consuming milk from animals on antibiotic treatment (Sharma et al. 2022). In an Italian awareness survey, very strong compliance was observed among senior university students where only 6% of students were found to violate correct dosage instructions and a proper intake time (Prigitano et al. 2018).

In third world countries, cost/finance plays a very important role in the decision-making process. Farmers are unable to visualize a holistic approach and mostly decide while keeping the cost in mind. This factor compels the farmers to decide and practice wrong. The antimicrobials use will rise to 67% by the end of 2030, and it will closely double in Russia, China, India, South Africa and Brazil (Von Boeckela et al. 2015). In the present study, the vast majority of farmers (90.4%) reported that they don’t find it cost-effective to complete the antibiotic course. Simultaneously, it’s too difficult to bear the expenses of a veterinarian. The same trend was observed in Jordan, 40.8% of respondents thought that the efficiency of antibiotics depends upon their price (Yusef et al. 2018). The non-sustainable use of antibiotics in dairy farms may lead to the food security issue in Pakistan.

Recommendations

We recommend the following steps to be taken into account to reduce the antibiotic burden

-

Prioritising the adoption of sustainable practices in antimicrobials and antibiotics use.

-

Address all aspects of food security, with particular emphasis on overlooked aspects such as food safety and nutrition

-

Invest in a comprehensive training program for younger veterinarians, enabling them to work independently and make informed decisions regarding antibiotic prescription.

-

Launch targeted awareness campaigns to educate farmers about knowledge, use, overuse and dangers of antibiotics. This will empower farmers to make informed decisions and resist peer pressure.

-

Develop and implement stringent antibiotic dispensing laws with an emphasis to prohibit antibiotic sales without prescription.

-

Promote the concept of ‘Integrated disease management’ in farming practices. Encourage farmers to maintain cleanliness on farms and prioritize disease prevention to reduce dependency on antibiotics.

-

Develop a comprehensive plan to address the financial barriers that discourage farmers from consulting the veterinarian. This may be addressed by providing subsidies to farmers or by improving services at State Owned Hospital.

-

Foster a strong relationship between veterinarians and farmers by emphasizing the importance of animal health over financial concerns. This trust will compel farmers to get veterinarian advice and decline to surrender to accept peer pressure.

Future research

We believe that the following future research areas must be addressed;

-

“Food security” and “sustainability” should be the core ideology in the business model of “dairy policy”

-

A data bank regarding farms needs to be developed, using the latest Information Technology apps and software. This should include farm size, the number of animals, disease burden, etc.

-

Integration of different fields (livestock department, veterinarians, medicine companies, farmers, media, food authority, etc.) is important to minimize antimicrobial misuse.

-

National policy on antimicrobial use needs to be developed. We need to accept that antimicrobial misuse is a problem and must set ways to minimize it.

Conclusion

The study highlights the ongoing challenges of food security in Pakistan, calling for rigorous efforts to focus on safety and nutritional aspects not only to abundance of food. The novel connection established on this critical issue in this research between the use and misuse of antimicrobials and food security. A substantial number of dairy farmers are less educated and their knowledge, attitude and practices regarding antibiotic use are very low and non-scientific. Financial constraints compel farmers to act carelessly which leads to antibiotic misuse. Their trust level in veterinarians’ advice is low and they are relying more on non-veterinary advisors for their animal’s health care. Rampant misuse of antibiotics, self-medication, lack of awareness and bad practices among farmers are some of the prevalent problems observed in this study. These are contributing factors towards antibiotic misuse, resistance and food security. To address these pressing challenges, a comprehensive awareness campaign is inevitable, aimed at filling the knowledge gap and promoting responsible antibiotic practices. Moreover, “Food security” and “sustainability” should be the core principle of “dairy policy”. Policymakers must collaborate with relevant stakeholders to implement stringent regulations that control antibiotic dispensing.

Data availability

The data is available to the corresponding author on demand

References

Ajibola O, Omisakin O, Eze A, Omoleke S (2018) Self-medication with antibiotics, attitude and knowledge of antibiotic resistance among community residents and undergraduate students in northwest Nigeria. Diseases 6(2):32–38. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases6020032

Alghadeer S, Aljuaydi K, Babelghaith S, Alhammad A, Alarifi MN (2018) Self-medication with antibiotics in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharma J 26:719–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2018.02.018

Al-Rasheed A, Yagoub U, Alkhashan H, Abdelhay O, Alawwad A, Al-Aboud A, Al-Battal S (2016) Prevalence and Predictors of Self-Medication with Antibiotics in Al Wazarat Health Center, Riyadh City, KSA. Biomed Res Int 34:54–62. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3916874

Ayepola OO, Onile-Ere OA, Shodeko OE, Akinsiku FA, Ani PE, Egwari L (2018) Dataset on the knowledge, attitudes and practices of university students towards antibiotics. Data Brief 19:2084–2094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.06.090

Bard AM, Main DC, Haase AM, Whay HR, Roe EJ, Reyher KK (2017) The future of veterinary communication: Partnership or persuasion? A qualitative investigation of veterinary communication in the pursuit of client behaviour change. PLoS ONE 12:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171380

Biel-Maeso M, Baena-Nogueras RM, Corada-Fernández C, Lara-Martín PA (2018) Occurrence, distribution and environmental risk of pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) in coastal and ocean waters from the Gulf of Cadiz (SW Spain). Sci Total Environ 612:649–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.279

Boeckel V (2018) Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Agric Sci 112:5649–5654. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503141112

Carvalho IT, Santos L (2016) Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of the European scenario. Environ Int 94:736–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.025

Chauhan AS, George MS, Chatterjee PB, Lindahl J, Grace D, Kakkar M (2018) The social biography of antibiotic use in smallholder dairy farms in India. Antimicrobial Resistance Infect Control 7:60–73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-018-0354-9

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16:297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

El-Zowalaty ME, Belkina T, Bahashwan SA, El-Zowalaty AE, Tebbens JD, Abdel-Salam HA, Vlček J (2016) Knowledge, awareness, and attitudes toward antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance among Saudi population. Int J Clin Pharm 38:1261–1268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0362-x

FAO (2003) Trade Reforms and Food Security: Conceptualizing the Linkages. FAO, UN, 2003

Gebeyehu E, Bantie L, Azage M (2015) Inappropriate use of antibiotics and its associated factors among urban and rural communities of Bahir Dar city administration, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 10:1–14

Giannitsioti E, Athanasia S, Plachouras D, Kanellaki S, Bobota F, Tzepetzi G, Giamarellou H (2016) Impact of patients’ professional and educational status on perception of an antibiotic policy campaign: A pilot study at a university hospital. J Glob Antimicrobial Resistance 6:123–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2016.05.001

Hasnain S (2020) Disruptions and food consumption in Islamabad. Geoforum 108:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.11.017

Kalunke RM, Grasso G, D’Ovidio R, Dragone R, Frazzoli C (2018) Detection of ciprofloxacin residues in cow milk: A novel and rapid optical β-galactosidase-based screening assay. Microchem J 136:128–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2016.12.014

Kramer T, Jansen LE, Lipman LJ, Smit LA, Heederik DJ, Dorado-García A (2017) Farmers’ knowledge and expectations of antimicrobial use and resistance are strongly related to usage in Dutch livestock sectors. Preventive Veternary Med 147:142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.08.023

Martínez JL, Coque TM, Baquero F (2015) What is a resistance gene? Ranking risk in resistomes. Nat Rev Microbiol 23:345–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro3399

McDougall S, Compton CW, Botha NS (2017) Factors influencing antimicrobial prescribing by veterinarians and usage by dairy farmers in New Zealand. NZ Veternary J 67:456–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2016.1246214

Mutua F, Sharma G, Grace D, Bandyopadhyay S, Shome B, Lindahl J (2020) A review of animal health and drug use practices in India, and their possible link to antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial Resistance Infect Control 9:103–116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00760-3

Pan M, Chu LM (2017) Transfer of antibiotics from wastewater or animal manure to soil and edible crops. Environ Pollut 231:829–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.051

Prigitano A, Romano L, Auxilia F (2018) Antibiotic resistance: Italian awareness survey 2016. J Infect Public Health 11:30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.02.010

Punjab Development Statistics (2021) Bureau of Statistics, Planning and Development Board. Government of the Punjab, Pakistan

Qamar FN, Ayub AM (2015) Prevalence and Consequences of Misuse of Antibiotics, Survey Based Study in Karachi. J Bioequivalance Bioavailibility 7:202–206. https://doi.org/10.4172/jbb.1000240

Redding LE (2019) Quantification of antibiotic use on dairy farms in Pennsylvania. J Dairy Sci 102(2):1494–1507. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2018-15224

Reddy AA (2018) Electronic national agricultural markets.”. Curr Sci 115(5):826–837. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v115/i5/826-837

Sharma G, Mutuab F, Dekab RP, Shomed R, Bandyopadhyaye S, Shomed BR, Kumarf NG, Graceb D, Deya TK, Venugopald N, Sahayd S, Lindahl J (2022) A qualitative study on antibiotic use and animal health management in smallholder dairy farms of four regions of India. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 10:1792033. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008686.2020.1792033

Smith MD, Floro MS (2020) Food insecurity, gender, and international migration in low- and middle-income countries. Food Policy 91:101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101837

Von Boeckela P, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfella B, Levina S, Robinsoni T, Teillanta A, Laxminarayan R (2015) Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:5649–5654. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1503141112

Wang X, Peng D, Wang W, Xu Y, Zhou X, Hesketh T (2017) Massive misuse of antibiotics by university students in all regions of China: implications for national policy. Int J Antimicrobial Agent 50:441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.04.009

Ye D, Chang J, Yang C, Yan K, Ji W, Aziz MM, Fang Y (2017) How does the general public view antibiotic use in China? Result from a cross-sectional survey. Int J Clin Pharm 39:927–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0472-0

Yusef D, Babaa AI, Bashaireh AZ, Al-Bawayeh HH, Al-Rijjal K, Nedal M, Kailani S (2018) Knowledge, practices & attitude toward antibiotics use and bacterial resistance in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. Infect, Dis Health 23:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2017.11.001

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to GCUL for providing all the resources for the study. We are also thankful to the students of the SDSC for pinpointing the exact locations of dairy farms, located in peripheral/suburbs of Lahore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF, AK and FS: Conceptualization, research design, software, data interpretation, reviewing of 1st draft, revision of draft, final approval for publication. NA and GZG: Data collection, software, data analysis, writing 1st draft, final approval for publication. MUH and LS: Research design, design of suitable methodology, data collection, data interpretation, writing 1st draft, revision of draft, final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval from “Board of Studies (0006-MPHILL-ENV-16)” of “SDSC, GCUL” was obtained, prior to conducting the study.

Informed consent

All participants were informed about the purpose of the study. They were informed about the confidentiality and secrecy of their date/information. Participants were briefed that the information will only be used for research purpose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Farhan, M., Awan, N., Kanwal, A. et al. Dairy farmers’ levels of awareness of antibiotic use in livestock farming in Pakistan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 165 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02518-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02518-9

- Springer Nature Limited