Abstract

This article addresses public attitudes towards government measures to contain preventable diseases in China in light of personal privacy and social safety controversies. Using a nationwide Internet survey of 776 Chinese adults and an online worldview database, we seek to explain the reason for causing differing public opinions on prevention policies and related governance issues. As Cultural Theory suggests, cultural biases impact public attitudes toward social policies. However, to our knowledge, culture theory has rarely been used to explain public differences in policies in China. So, study 1 conducted an exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and found that the four-factor model of cultural worldviews: egalitarianism, hierarchy, individualism, and fatalism is still a feasible assessment tool for worldviews. Then, in studies 2–4, we explored how cultural worldviews influence Chinese public policy support. Study 2 involved an online worldview database and found that by trusting the government, hierarchists trust the policies proposed by the government. Study 3 and Study 4, based on the revised cultural scale in Study 1 and surveys during the epidemic period, found that compared to hierarchists and egalitarians, fatalists and individualists were less likely to support COVID-19 responses. In study 3, we further found that along with the risk perception levels growing, fatalists’ resistance towards epidemic prevention policies will disappear under high-risk perception conditions. Study 4 also found that hierarchists and egalitarians with higher trust in government tend to support COVID-19 responses. Hierarchists will be more supportive of the government with the increased public’s perceived threats. In conclusion, cultural worldviews have different impacts on policy support, and the relationship between cultural worldviews and policy support is influenced by public attitudes toward authorities and the perceived threats they face. Lastly, risk management and communication implications are discussed, such as establishing trust between individuals and authorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s context of globalization and industrialization, the world is undergoing constant change and facing various threats, including financial collapse and polarization of wealth (Seib, 2016), climate change (Kim and Kim, 2019), and the COVID-19 pandemic (Bavel et al. 2020). In the recent COVID-19 pandemic, public policies, including social restrictions, quarantines, the prohibition of public activities, and travel registration, played a vital role in epidemic prevention and control (Haug et al. 2020). In this context, there were noticeable cultural differences in citizens’ acceptance of policies; for example, collectivists have higher mask-wearing rates (Lu et al. 2021) and are more willing to abide by prevention and control policies (Savadori and Lauriola, 2021). In contrast, individualists are more resistant to COVID-19 responses (Maaravi et al. 2021). Although cross-cultural studies have found that culture affects residents’ acceptance of policies, how culture influences public supportive attitudes regarding restrictive policies is still being determined. It is crucial to gain insight into the cultural factors that predict adherence to protective policy measures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cultural theory explains the difference in public attitudes towards government policies from the perspective of how we understand the way this society is composed (i.e., cultural worldviews), which holds that the public does not simply calculate the costs or benefits of policies but also evaluates the impact of public policy on their preferred ways of life (Swedlow, 2011). The Cultural Theory has been widely applied to different fields, from climate change (Jones, 2014) and child vaccination (Song et al. 2014) to gun control and government surveillance (Gastil et al. 2011). However, cultural theory was proposed and empirically tested in Western culture (Douglas and Wildavsky, 1982; Wildavsky, 1987). Studies found that cultural theory may not apply to other countries beyond America, and cultural ideas and norms change as they are interpreted and reinterpreted in the worldviews of culture-bearers when confronted with personal and social experiences (Voorhees, 2022). Dake’s cultural theory scale (CTS) and Kahan’s cultural cognition scale (CCS) have been widely used for assessing cultural values (Dake, 1991, 1992; Kahan et al. 2007; Kahan et al. 2010). However, the reliability and validity of measurement tools of cultural values need to be further confirmed (Chauvin and Chassang, 2022; Dryhurst et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2016). Therefore, given the feasibility of cultural theory in the West to explain differences in public attitudes toward government policies and the fact that it has not been proven to have the same explanatory effect in China, our research must examine the mechanisms of cultural values shaping the Chinese public attitude in governments’ policies. To offer theoretical insights into better understanding the roles of cultural worldviews in policy attitudes, we first explore the applicability of cultural theory measurement scales in China and then further analyze the indirect effects of trust in government between cultural worldviews and policy attitudes and the moderation effect of risk perception. We expected to inform communication strategies that seek to navigate trust in managing pandemics through further research.

Cultural theory

The internal mechanisms of public attitude toward government policies have been a significant area of government studies over the last few decades (James and Nakamura, 2015). This article sheds new light on this area by utilizing four dimensions of cultural worldviews proposed by cultural theory (CT). CT, also known as the grid-group theory, was originally a culture associated with the social dimensions observed in social institutions. It was developed by Mary Douglas (Douglas and Wildavsky, 1982) and has since been enlarged by many other scholars (Dake, 1991, 1992; Kahan et al. 2007; Thompson et al. 1990; Trousset et al. 2015). Cultural worldviews are individuals’ general beliefs in all social relationships and the world. In specific situations, they influence individuals’ attitudes and perspectives toward events (Dake, 1991, 1992). According to Cultural Theory, the public prefers how society is organized, and risk perceptions help reinforce these preferences. CT posits that cultural worldviews can be represented by their location from a two-dimensional space of “group” and “grid” (Douglas and Wildavsky, 1982; Wildavsky, 1987; Ney and Verweij, 2014).

From the degree of social members constrained by the social group they belong to, the “group” dimension evaluates whether individuals prefer to live in a society that encourages collective identity, social bonds, and cooperation (high group) or a society that encourages individual differences, self-reliance, and competition (low group); Based on the recognition degree of social stratification, the “grip” dimension assesses the extent to which individuals are more inclined to hierarchical- or gender-based social structures and believe that it should be constrained through social rules (high grid) as opposed to those that encourage equal opportunity, responsibility, and power regardless of gender or class (low grid). Combining the group and grid dimensions, Douglas and Wildavsky (1982) proposed a matrix reflecting four cultural worldviews (see Fig. 1): Hierarchy, Egalitarianism, Individualism, and Fatalism. Hierarchists attach importance to group welfare and procedural rules and are committed to maintaining existing power structures to ensure social stability and avoid deviance. If rules or technology are proven safe by authorities, they are more likely to believe that it can improve the quality of life and tolerate its adverse effects. Since they recognize authority in social decision-making, they are classified in the high group-high grid quadrant. Egalitarians also emphasize group welfare but oppose social stratification. They value fairness and social justice, advocate for an equal voice among participants in decision-making, and are skeptical of every hypothetical source that may lead to social inequality, such as free commerce and authority (Leiserowitz, 2005), with a tendency of high group-low grid. Individualists also doubt authority and fixed procedures; therefore, they fear restrictions on their autonomy and freedom, avoid collective decision-making, and are hesitant about external supervision. They also tend to seek to maximize interests, so they believe that stakeholders’ opinions should be valued in social decision-making, with a tendency for a low group-low grid. Finally, fatalists hold that humans cannot control most things in social life. A person’s future is primarily determined by fate, showing group alienation and distrust of authorities (Dake, 1992; Trousset et al. 2015), which reflects a low group-high-grid tendency.

The common approaches for assessing cultural worldviews are the Cultural Theory Scale (CTS) and the Cultural Cognitive Scale (CCS). The initial effort to operationalize cultural theory in survey research was provided by Dake and colleagues (Dake, 1991, 1992), and CTS naturally appeared. CTS has been used in many studies after that for assessing one of the four dimensions: Hierarchy, Egalitarianism, Individualism, and Fatalism. CTS has also been employed in dozens of studies focusing on environmental, technological, and other policies and risks (Bordat-Chauvin and Elodie, 2016; Song et al. 2014; Swedlow et al. 2016; Yang, 2015). However, researchers also found that each subscale’s reliability, discriminant validity, and predictive validity could have been better, and this problem has yet to be significantly improved in the modified version (Palmer, 1996; Swedlow et al. 2016). Therefore, based on their “cultural cognition” framework, Kahan and his colleagues (2007) reconstructed the dimensions and proposed CCS, which directly corresponds to the group-grid dimension from the individualism-collectivism dimension and the hierarchy-egalitarianism dimension, respectively (see Fig. 2). Although CCS has been proven to have a high degree of validity in American studies (Kahan et al. 2010), the reliability and validity of CCS and CTS must be further explored in collectivist countries (Dryhurst et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2016). Studies in Japan and South Korea found that CTS subscales have a low internal consistency (Kim and Kim, 2019; Iwaki, 2011; Yang, 2015), and the reliability of the individualism-communitarianism dimension of CCS is lower than 0.6 in collectivist cultures such as Japan, South Korea, and Mexico, which is far lower than the 0.8 found in typical individualistic countries such as Britain and the United States (Dryhurst et al. 2020). Kahan (2012) also indicated that the proposal for the CCS scale is based on historical issues in the United States. It is conceivable that its structural and predictive validity does not apply in some non-US regions. Therefore, the feasibility of CTS and CCS should be further discussed in China (Liu and Yang, 2023).

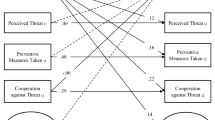

Some studies have tried to use self-designed questionnaires or the World Value Survey (WVS) database to explore the cultural orientation of the Chinese public. Chai et al. (2009) used the WVS database to find that China has a low group-high-grid tendency, and the result has been confirmed in other studies (Yin et al. 2014; Zeng et al. 2020). Researchers also found differences in public attitudes towards water resource management strategies and environmental protection among different cultural worldviews (Yin et al. 2014; Zeng et al. 2020). Xue et al. (2016) proposed a revised scale, which integrated CTS and CCS, including four dimensions: hierarchy, individualism, egalitarianism, and fatalism. Subsequent studies found that the multidimensional reliability of the revised CTS scale remained between 0.70 and 0.82, and the validity of the revised scale is acceptable (Xue et al. 2016; Xue et al. 2021). It further indicates that cultural theory can be used for research in China. CTS and CCT are essential tools for exploring cultural theory. In order to further explore the impact of cultural worldviews on public attitudes toward government policies in China, we first explored the suitability of the standard four-factor CTS model and two-factor CCS model; then, we tested a working model in which cultural worldviews had a central role in shaping the attitude toward government policies. The model assumed that cultural worldviews could influence public tendency towards government policies through trust in government, and these relationships are regulated by risk perception (Fig. 3).

Mediated moderation model (Studies 2–4); government trust mediates the influence of cultural worldviews on policy support (Study 2), government trust mediates the influence of cultural worldviews on COVID-19 government policy support (Study 3), and the moderating role of risk perception in the mediated moderation model(Study 4).

Cultural worldviews and policy support

Closely related to policy support are cultural worldviews. Studies found that compared to political orientations and party identification, cultural worldviews are more suitable for predicting public attitudes toward policies (Gastil et al. 2011). Cultural worldviews support different public policies, such as egalitarians supporting environmental protection and mandatory vaccination policies (Song et al. 2014; Xue et al. 2016). Korean studies have also found that egalitarians support health policies (Lee and Park, 2015). Hierarchists support vaccination policies and believe the government should decide everything for citizens (Song et al. 2014). However, Siegrist and Bearth (2021) also found that hierarchy does not impact the public acceptance of epidemic control measures. In addition, fatalists and individualists resist environmental protection and vaccination policies (Song et al. 2014; Xue et al. 2016). Individualists value personal freedom, and the public often views personal freedom as an essential reason for opposing policies such as COVID-19 vaccination, mandatory masks, and lockdowns (Peng, 2022). Previous studies confirmed this conclusion and found that respondents with high individualism scores exhibit more vigorous opposition to government epidemic prevention policies, such as closing public places, the mandatory wearing of masks, and vaccination (Dryhurst et al. 2020; Liu and Yang, 2023; Peng, 2022; Siegrist and Bearth, 2021). Further, high-group individuals (hierarchist and egalitarian) are more likely to collaborate, while low-group individuals (individualist and fatalist) are more likely to act independently. Although hierarchists and egalitarians hold a positive attitude toward policies that bring social benefits, hierarchists aim to abide by social rules, and egalitarians start from the perspective of group interests (Song et al. 2014; Trousset et al. 2015). Individualists and fatalists will more likely emphasize the negative impact of current policies on people and try to avoid the inconvenience caused by current policies (Song, 2014). Therefore, to safeguard interests and avoid supervision, individualists, and fatalists are likely to question the necessity of policy implementation (Song et al. 2014; Trousset et al. 2015). Thus, the first hypothesis states that cultural worldviews significantly predict policy support. In particular,

Hierarchists (H1a) and egalitarians (H1b) tend to support government policies, whereas individualists (H1c) and fatalists (H1d) tend to object to government policies.

Cultural worldviews, policy support, and government trust

The rapid spread of information in the “risk society” gives rise to a variety of comments about scientific facts; the public needs to establish trust with institutions or some information sources (Tabery and Pilnacek, 2020), which not only includes trust in justice institutions (such as courts or the police) and political institutions (such as government) (Newton and Zmerli, 2011), but it also corresponds to the belief that proper measures and policies will work effectively to address current problems (Bostrom et al. 2019; Tabery and Pilnacek, 2020). Since attitudes toward social order and authorities differ among cultural worldviews, Hierarchists believe that authorities should make reasonable solutions to crises and blame public deviants for the current issues (Caulkins, 1999; Swedlow, 2014). However, individualists and fatalists have lower trust in authorities due to their obsession with individual choice and fickle life attitude (Bachem et al. 2020; Soiné et al. 2021). Thus, based on compelling evidence from cultural theory, the second hypothesis states that cultural worldviews will be a significant predictor of government trust. In particular,

Hierarchists (H2a) and egalitarians (H2b) have a positive effect on government trust, whereas individualists (H2c) and fatalists (H2d) harm government trust.

The more confidence the public has in societies and institutions, the more support they have for their vaccination policies (Rönnerstrand, 2013). Studies found resistance to the government’s quarantine and vaccination policies among the younger generation, who generally have low trust in societies (Bogart et al. 2021; Nivette et al. 2021). Hypothesis 3 states that participants who have more trust in the government are more likely to support government policies. In contrast, Hypothesis 4 proposes that government trust mediates cultural worldviews and citizens’ supportive attitudes toward governmental management. In particular,

Hierarchists (4a) and egalitarians (4b) tend to perceive greater trust in government, which predicts higher support for policies. Individualists (4c) and fatalists (4d) have lower trust in government and are less supportive of policies.

Although there is no direct empirical evidence showing that government trust mediates the relationship between cultural worldviews and citizens’ supportive attitudes toward governmental policies, some studies back it up in an indirect way, such as Baumgaertner et al. (2018), who found that government trust plays a mediating role in the impact of political ideology on support for vaccination policies.

Cultural worldviews and support for government COVID-19 policies

The COVID-19 outbreak put people worldwide in fear and uncertainty (Jost et al. 2003). When faced with a threat, the public is likelier to stick to their established social values; in other words, they consider their default interpretation of society as the best way to maintain a sense of clarity of current situations (Rosenfeld and Tomiyama, 2021). For example, in crises, an authoritarian has a higher trust in the authoritarian government (Torres-Vega et al. 2021). The perception of risk includes two fundamental ways in which humans respond to threats (Slovic et al. 2004). The first is the sense of the severity of the outbreak, especially the effects on physical health. The second is their vulnerability in the pandemic, which refers to someone’s likelihood of contracting the virus (Finucane et al. 2000). People’s responses to the epidemic have varied widely, and cultural worldviews interact with risk perception to influence public attitudes toward government policies.

The four cultural worldviews pointed out by cultural theory do not exist in a single form of socialization. However, cultural theory is also known as the cultural theory of risk. Different cultural worldviews identify and define risks threatening their preferred way of life (Dake, 1991). Researchers also point out that cultural theory is about how society is composed and operates, and cultural worldviews constitute commitments and predictions. Individuals’ attitudes and behaviors influence these commitments and predictions through their daily practice, which is influenced by the environment. Change can come from within culture, with very few people exhibiting only one cultural worldview and, in many cases, exhibiting ‘multiple selves’. People’s basic assumptions about nature, human nature, risk, and justice have not changed. However, they will adjust their views toward specific things based on the actual situation and the information they receive (Johnson and Swedlow, 2019a; Verweij et al. 2011). Therefore, although it is well established that cultural worldviews can explain different attitudes toward political and social events (Swedlow, 2011), how cultural worldviews shape responses to attitudes toward government and mandatory policies remains to be determined.

Cultural theory points to two alternative patterns of how cultural worldviews interact with risk perception to influence policy support: first, hierarchists and egalitarians identify with the existing social order and are highly sensitive to threats, so they tend to support stricter policies (Duckitt and Fisher, 2003; Duckitt and Sibley, 2009). One explanation for this tendency to support mandatory policies in crises is that people mainly want to restore the perceived loss of control caused by exposure and social threats (Matheson, 2018). Secondly, out of self-protection, people may no longer stick to their original fatalism value (Bachem et al. 2020); risk perception makes fatalists and individualists less negatively responsive to authorities and mandatory policies. Wang (2022) found that individuals with low individualistic worldviews, regardless of their level of risk perception, are more likely to support current epidemic prevention measures such as maintaining social distancing; however, individuals with high individualistic worldviews will support policies when they believe they are in a high-risk situation. Thus, we examine these two hypotheses to provide insight into how cultural worldviews influence government trust and individual supportive attitudes toward government COVID-19 responses. In particular,

Hypothesis 5 proposes that hierarchists and egalitarians are more supportive of authorities (H5a) and epidemic prevention policies (H5b) under high-risk conditions.

Hypothesis 6 posits that individualists and fatalists are less opposed to authorities (H6a) and epidemic prevention policies (H6b) under high-risk conditions.

Summary of predictions and overview of studies

The constructs examined in our literature review can be summarized in a general model, which we aimed to test by examining how well it could account for the data in China (notably the data collected during the COVID-19 epidemic in China). In Study 1, we validated cultural worldview instruments, including CTS and CCS, with a Chinese sample. Study 2 explored the mediating effect of government trust between cultural worldviews and public support for government policies using the WVS-7 dataset. According to the central role of risk perceptions in influencing the attitudes of authorities and policies in crisis conditions, Study 3 examined the effect of cultural worldviews on policy support and the regulating role of risk perception. Study 4 explored how government trust mediates and how risk perception regulates the relationship between cultural worldviews and policy support. In doing so, we aimed to create a general framework incorporating cultural worldviews and social rules into understanding COVID-19 Policy Governance (see Fig. 3). It is also essential to gain insight into the reasons behind the obsession with cohesion and deference to authority. Therefore, this study aims to discuss the complex interplay between social and cultural factors when determining public supportive attitudes toward government policies during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study 1: The feasibility of Cultural Worldviews Scale in China

Overview

In order to explore the influence of cultural worldviews on public attitudes, we first examine the applicability of current scales in China. The widely adapted scales are CTS (Dake, 1991, 1992) and CCS (Kahan et al. 2007). Therefore, study 1 tests the reliability and validity of the two scales to find the most appropriate scale for the rest of the studies.

Participants

We recruited 783 participants from China via an online survey system from the school psychology department. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were under the ethical standards of the Department of Psychology Institutional Review Board (reference number: IRB/ 23-014) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. We collected the first sample wave from February 20 to 29, 2020 (499 valid respondents, after excluding six participants for irrational duplication of choices on different issues). Respondents were mainly aged between 20 and 39; the sample was 39% male and 61% female. The distribution of education was as follows: 11.4%, 71.3%, and 17.2% for senior high school and below, vocational school, and college, respectively. Most of the sample (72%) were employed, 26% were students, and 3% were retired. The majority of respondents (75%) were from low-risk areas. In comparison, 12% came from areas with high epidemic incidences, and 10%incidents lived in areas that used to be considered high-risk. We collected the second wave of the sample data from December 14 to 24 (277 respondents). Here, female respondents accounted for 62% of the total sample, and participants mainly ranged from 18–25 years old. The distribution of education was as follows: 28.9%, 47.3%, and 23.8% for high school, university undergraduates, and graduates, respectively. Most respondents (86%) had high health levels, and 5.8% had direct experience in high-risk areas.

Measures

Cultural worldviews were measured using the translated versions of CTS and CCS (Xue et al. 2016). Dake’s (1991, 1992) CTS contained 12 items to assess four dimensions: Hierarchy (e.g., respect for authority is one of the most important things that children should learn); Egalitarianism (e.g., the world would be a more peaceful place if wealth was divided more equally among nations); Individualism (e.g., the government interferes too much in our everyday lives); Fatalism (e.g., I really do not have much control over my future). Kahan’s (2012) CCS scale consisted of 12 items assessing two bipolar dimensions (hierarchy-egalitarianism and individualism-communitarianism) in the following way: Hierarchy (e.g., we have gone too far in pushing equal rights in this country); Individualism (e.g., the government should stop telling people how to live their lives); Egalitarianism (e.g., our society would be better off if the distribution of wealth were more equal); Communitarianism (e.g., sometimes the government needs to make laws that keep people from hurting themselves). Given that two CCS and CTS items were identical (e.g., we need to reduce inequalities between the rich and the poor dramatically and between men and women; the government interferes too much in our everyday lives), 22 cultural worldview items were analyzed. All items employed the same rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with a higher score reflecting a higher tendency toward cultural worldviews.

Data analysis and results

Data were analyzed using Mplus 7.0 to assess the suitability of CCS and CTS for Chinese samples. First, we conducted a separate confirmatory factor analysis for the four-factor CTS and two-factor CCS models using the first wave of collected data (n = 499). Based on the finding that the load of each potential variable was greater than 0.5, the model fit was assessed by five fit indices: χ2/df, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewisindex (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). According to Kline (2005), an acceptable model fit is defined as χ2/df < 3, CFI > 0.90, TLI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08, 90% CI = [0.05, 0.10] and SRMR < 0.10. Following this, the confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, which showed that the two-factor CCS model fit the data poorly, with most of fit indices failing to meet any of the criteria for acceptable fit: χ2/df = 8.40, CFI = 0.72, TLI = 0.65, RMSEA = 0.12, 90% CI = [0.11,0.13] and SRMR = 0.08; the internal consistency coefficient of two dimensions were hierarchy-egalitarianism (α = 0.63) and individualism-communitarianism (α = 0.65); Dake’s CTS model first the data better, but still did not meet the criteria: χ2/df = 4.96, CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.84, RMSEA = 0.09, 90% CI = [0.08,0.10] and SRMR = 0.07, the Cronbach’s α of four dimensions are hierarchy (α = 0.77), egalitarianism (α = 0.66), individualism (α = 0.48), and fatalism (α = 0.63). Although the validity indexes of the CCS four-factor model were better than the CTS two-factor model, the results show that neither CCS nor CTS was suitable for Chinese samples.

Second, we combined CCS and CTS to conduct an exploratory principal axis factor analysis using all 22 items from both scales to find a suitable measure of worldviews. The analysis was conducted using Mplus 7.0 and the first-wave sample, as shown in Table 1. The result showed that the five-factor model fit the data perfectly, with all fit indices considered acceptable: χ2/df = 2.11, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI = [0.04,0.06] and SRMR = 0.03. However, as the fifth factor of communitarianism did not apply to the current research, we only used the four dimensions of hierarchy, egalitarianism, individualism, and fatalism, considering the current situation, the theoretical basis of Cultural Theory, and a previous study (Xue et al. 2016). The modified four-factor model was still acceptable in the following confirmatory factor analysis, conducted using Mplus 7.0 and the second-wave sample (see Table 2). The load of each item was greater than 0.5 in its dimension. All fit indices were in line with the acceptable standards: χ2/df = 1.56, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI = [0.02,0.06], and SRMR = 0.04; Cronbach’s α of four dimensions respectively were hierarchy (α = 0.72), egalitarianism (α = 0.74), individualism (α = 0.72), and fatalism (α = 0.69). These findings proved that this theoretical structure’s revised scale was reasonable and could be used.

Discussion and Introduction to Study 2

Previous and current research showed that CTS and CCS are unsuitable for Chinese samples (Xue et al. 2016), so a feasible cultural worldview scale was obtained through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The validity and reliability of the revised scale were assured through further studies. The Cronbach’s ɑ of each subscale in the revised scale in two wave data ranged from 0.68 to 0.72, and the reliability of each subscale was more significant than 0.6. In confirmatory factor analysis, the four-factor model fitted well. Therefore, the revised cultural worldview scale has good reliability and validity and can be used for future research. In the cultural worldviews proposed in individualism, it is unreasonable to assume that this will also apply to collectivist culture before explaining its application mechanism (Oyserman, 2017). Therefore, the main effect of cultural worldviews on policy support is discussed in research 2–4. First of all, it is still being determined whether the cultural worldview still adheres to the inherent view of the government in a country with such a high power distance and collectivism as China. Therefore, Study 2 explores the intermediary role of government trust in the impact of cultural worldview on policy support.

Study 2: The influence of cultural worldviews on policy support: the mediating role of government trust

Data sources

The World Values Survey database (WVS) surveys individuals’ cultural values and attitudes to family, poverty, security, and social tolerance. The Chinese portion of the WVS-7 questionnaire was obtained from 26 September 2018 to 12 October 2018, through field investigations and interviews with 12 universities from different regions across China (Haerpfer et al. 2020). The respondents were Chinese citizens aged between 18 and 70 years old who had lived in districts and counties within 31 provinces of mainland China for more than six months (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). The respondents in the WVS database were sampled proportionally to reflect the distribution of the national population density. This study’s final sample of valid participants was 2868 (55% female, Mage = 44.31, SD = 14.47).

Index Selection

Cultural worldviews were measured referring to culture theory, using one question to measure each dimension of the cultural worldview. The corresponding questions about hierarchy and egalitarianism are the degree to which respondents recognize “People obey their rulers” and “The state makes people’s incomes equal” as the essential characteristics of democracy, respectively. The corresponding question about individualism and fatalism is how respondents agree with “People should take more responsibility to provide for themselves” and “Hard work doesn’t always bring success—it’s more a matter of luck and connections”, respectively. Four items employed the same rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree), with lower ratings reflecting a higher tendency toward cultural worldviews.

Support for government management was defined as respondents’ approval of government actions, using three items to measure it. Specifically, this included questions about whether people think the government has the right to “Keep people under video surveillance in public areas,” “Monitor all e-mails and any other information exchanged on the Internet,” and “Collect information about anyone living in [COUNTRY] without their knowledge.” All the items were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely should have the right) to 4 (definitely should not have the right). The inspection of initial eigenvalues, which was corroborated by a principal component analysis, showed that by retaining one factor (65.27% of explained variance after rotation) that was obliquely rotated (PROMAX), we obtained a reliable total score for support for government management (α = 0.86), with higher ratings reflecting a more positive attitude towards government policies (M = 2.80, SD = 0.79).

Government trust was assessed by two questions. Items including “Confidence in the government” and “Confidence in the political parties” were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (a great deal) to 5 (none at all). A preliminary principal component analysis showed that by retaining one factor (83.86% of explained variance after rotation) that was obliquely rotated (PROMAX), we obtained a reliable total score for government trust (α = 0.81); the score was then reverse computed, with higher ratings reflecting a more positive attitude of government (M = 3.36, SD = 0.57).

The following covariates were included in the current study: age, gender, religion (rated on the scale of “importance of god” from 1-not at all important to 10-very important, with higher ratings reflecting stronger religious beliefs, M = 2.79, SD = 2.53), educational level (rated on the scale from 0-no education to 8-doctoral or equivalent, M = 2.85, SD = 1.91), subjective social class (rated based on the question “which social class does people think they belong to in society?” with answers ranging from 1-upper class to 5-lower class, reverse computed, M = 2.30, SD = 0.80), the scale of incomes (rated on the scale of “which level do people think they belong to if the national people’s average household income is divided into ten equal parts” from 1-lower step to 5-tenth step, with higher ratings reflecting better living situations, M = 4.16, SD = 1.85). Previous studies have found that variables such as age, gender, religion, and education level affect policy support (Gerber and Neeley, 2005).

Data analysis and results

The data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0, and a hierarchical ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used to estimate the incremental evaluation of R2 at each step (Cohen et al. 2003). In light of the mediated model propositions and significant correlations between potential mediators (Table 3), we tested for mediation using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4) (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Path coefficients and bootstrap bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) (5,000 samples) were estimated in the mediation model. Multicollinearity tests showed tolerance values well above 0 and VIF values below the conventional cutoff value of 10 (Cohen et al. 2003).

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among composite scores that either control or do not control for covariates (above or below the diagonal, respectively) are presented in Table 3. Scores of cultural worldviews are presented in descending order: egalitarianism (M = 7.67, SD = 2.54), hierarchy (M = 6.34, SD = 2.92), individualism (M = 5.77, SD = 2.81), and fatalism (M = 3.70, SD = 2.71). Table 3 shows that policy support is associated with cultural worldviews (i.e., hierarchy and fatalism) and government trust. Government trust was associated with all types of cultural worldviews. Government trust was no longer associated with egalitarianism after researchers controlled sociodemographic factors. Other correlations among the variables do not differ by covariates. A greater hierarchy was associated with increased government trust, policy support, and egalitarianism. Egalitarianism was associated with increased individualism and decreased fatalism. In turn, greater fatalism was negatively associated with policy support, government trust, and individualism. Government trust was associated with increased policy support to the same extent as hierarchy. In contrast, fatalism was associated with lower government trust. Hierarchy was positively associated with egalitarianism and individualism and was negatively associated with fatalism. Egalitarianism was positively associated with individualism and was negatively associated with fatalism.

Using OLS regressions, we entered covariates and cultural worldviews. As presented in Table 4, cultural worldviews and covariates explained 4% of the variance in government trust and 3% in policy support; government trust explained an additional 1% in variance when predicting policy support. As predicted in H1a and H2a, hierarchy emerged as a significant predictor of government trust (β = 0.02, t = 4.76, p < 0.001) and policy support (β = 0.04, t = 7.28, p < 0.001). Government trust was negatively associated with individualism (β = −0.01, t = −3.14, p < 0.01) and fatalism (β = −0.02, t = −5.67, p < 0.001). Thus, H2c and H2d are supported. Fatalism was also negatively associated with policy support (β = −0.01, t = −2.29, p < 0.05), and therefore H1d is supported. However, the negative impact of fatalism on policy support disappeared after adding government trust into the predicting model of policy support. Since government trust was positively associated with policy support (β = 0.14, t = 5.54, p < 0.001), H3 was supported.

Using the PROCESS macro, the total indirect effect of hierarchy was significant regarding policy support (95% CI = [0.03, 0.05]). The bias-corrected 95% CI for the indirect effect via government trust (95% CI = [0.001, 0.004]) did not contain 0, indicating a significant mediation role. Although it is a small effect size, H4a could still be proved since indexes were not designed to measure cultural worldviews; therefore, items only measured policy support in extreme situations.

Discussion and Introduction to Study 3

Previous studies showed that the Chinese public has a high-grid-high group tendency (Chai et al. 2009), so hierarchy and egalitarianism are predominant in China (Zeng et al. 2020). Study 2 confirmed this result using the open database. Study 2 shows that egalitarianism is positively correlated with hierarchy and individualism, fatalism is negatively correlated with hierarchy and egalitarianism, and hierarchy and egalitarianism are more likely to support mandatory policies and have more trust in government. Further regression analysis also found that the cultural worldview has a significant predictive effect on policy support. In the intermediary path analysis, government trust plays a mediating role in the positive impact of hierarchy on policy support, and individualism and fatalism were less likely to trust the government. Policy support refers to the level of support for government information monitoring behavior in daily life. Whether cultural worldviews influence public supportive attitudes toward government epidemic responses remains to be studied. The outbreak of the epidemic can put the public in a state of uncertainty and threat to survival (Jost et al. 2003), which is an opportunity to explore whether the impact of cultural worldviews on policy support is influenced by risk perception. Therefore, it is necessary to include epidemic factors such as risk perception in Study 3 to understand cultural worldviews’ influence on policy support in crises.

Study 3: the effect of cultural worldviews on epidemic policy support: the moderating role of risk perception

Participants and measures

Based on the epidemic data from November 2020 (n = 277), Study 3 explored whether risk perception moderated the effect of cultural worldviews on epidemic policy support during the COVID-19 pandemic. After reading the instructions, participants completed the questionnaires.

Policy support was measured based on Haug et al.’s (2020) work. We asked respondents to support or oppose ten different epidemic prevention policy proposals, such as “The government restricts the number of Entry-Exit to control the epidemic.” All the items were measured on a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The principal component analysis showed that one factor (59% of the explained variance after rotation) was obliquely rotated (PROMAX). The higher the score, the more likely the public supported the epidemic prevention policies (α = 0.92).

Cultural worldviews were measured using the modified scale from Study 1. All 12 items were separated by four factors and were measured on a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Details, including the mean and standard deviation, are presented in Table 2.

Risk perception was defined as awareness of the current COVID-19 pandemic based on the risk perception index developed by Leiserowitz (2003) and Kaufman et al. (2020). It was separated into two factors: vulnerability of risk and severity of risk. Vulnerability of risk, namely the possibility of contracting the COVID-19 virus, was measured by one item: “I have a high chance of being infected”. The severity of risk, namely the perception of the danger level of the current crisis, was measured by five items, such as “This pneumonia is likely to result in the patient’s death.” The principal component analysis showed retaining one factor (52% of the explained variance after rotation) that was obliquely rotated (PROMAX). All items were measured on a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and computed into a total score with higher ratings reflecting higher degrees of risk perception (α = 0.71).

Respondents’ gender, age, education levels, and living area were all assessed using single items.

Data analysis and results

Description of demography variables: 62% of the 277 participants were female. The proportion of middle and high school students with education level and below, undergraduate students, and graduate students is 28.9%, 47.3%, and 23.8%, respectively, and the proportion of the group under 18 years old, 18–25 years old, 26–30 years old, 31–40 years old, 41–50 years old and 51–60 years old is 18.1%, 49.1%, 3.6%, 11.6%, 13.4% and 4.3%, respectively. Most respondents (86%) have a high level of health. In comparison, 5.8% have direct experience with the epidemic and have lived in areas with high incidences of the epidemic.

Descriptive statistics and correlations were separately presented outside the brackets and below the diagonal in Table 5. Scores of cultural worldviews were presented in descending order: hierarchy (M = 2.85, SD = 0.67), egalitarianism (M = 2.77, SD = 0.63), individualism (M = 2.25, SD = 0.69), and fatalism (M = 2.14, SD = 0.76). Table 5 shows that hierarchy and egalitarianism were positively associated with policy support. At the same time, great individualism was related to decreased policy support. Risk perception was positively associated with all cultural worldviews, and policy support and cultural worldviews had a significant positive correlation.

In predicting policy support, we first centralized all variables except the demographic factors. Then, using OLS regressions, we entered demographic factors, cultural worldviews, and risk perception in the first step and the interaction variables of cultural worldviews and risk perception in the second step. As presented in Table 6, cultural worldviews and covariates explained 20% of the variance in policy support. Hierarchy was positively associated with epidemic prevention policy support (β = 0.12, t = 3.02, p < 0.01). In contrast, individualism was negatively associated with pandemic prevention policy support (β = −0.14, t = −3.11, p < 0.01). As such, H1a and H1c were supported. The interaction between fatalism and risk perception positively predicted policy support (β = 0.17, t = 2.65, p < 0.01).

We analyzed the significance of the effect of fatalism on policy support at different risk perception levels based on the Johnson-Neyman method (Spiller et al. 2013). Figure 4 shows that fatalism significantly negatively affects epidemic prevention policy support when risk perception is lower than 0.67 (β = −0.15, t = −2.43, p = 0.02), and this negative effect disappeared when risk perception was higher than 0.67 (β = −0.03, t = −0.53, p = 0.59). Hypothesis 6b was partially supported.

Discussion and Introduction to Study 4

Study 3 found that cultural worldviews affect epidemic prevention policy support, in which hierarchists tend to support government policies and individualists are more resistant to government management. Study 3 also found that the effect of fatalism on policy support varies with changing perceptions of risk. Fatalists object to current pandemic prevention policies when they are at low-risk perception conditions. However, when they hold that they are at high-risk perception situations, they will no longer oppose government crisis responses. Cummings (2014) found that in high-risk perception situations, people are more likely to trust institutions that respond to the pandemic. Although the majority of respondents in this study came from low-risk areas of the epidemic, some studies have also found no significant difference in the severity of risk perception between residents in high-risk areas (such as Hubei at the beginning of the epidemic) and other regions. Therefore, after implementing a nationwide lockdown, the severity of individual risk may not be affected by their place of residence (Wang, 2022).

We found that all dimensions of cultural worldviews were significantly positively correlated with the perception of epidemic risk, consistent with previous cultural theory research results. Johnson and Swedlow, 2019b have also found that all cultural worldviews showed a high level of attention to the virus when facing the Zika virus (a public health emergency in 2014). In further regression analysis 1, egalitarianism and fatalism positively impact risk perception. After controlling demography variables, hierarchy positively predicted risk perception. This result is consistent with the conclusion of Kahan et al. (2010). Under high-risk threat situations and strict national epidemic prevention measures, egalitarianism that focuses on group interests and hierarchy that wants to maintain authority naturally takes the current threat seriously. Fatalists who want to protect themselves may try to pay more attention to the crisis (Xue et al. 2016).

Although it was found in Study 3 that risk perception affected the influence of cultural worldview on epidemic prevention policy support, whether government trust can play a mediating role and whether the effect changes with risk perception will be discussed in Study 4.

Study 4: The effect of cultural worldviews on epidemic policy support, the mediating role of government trust, and the moderating role of risk perception

Participants and measures

Based on the survey data from February 20 to 29, 2020 (n = 499), Study 4 explored whether government trust mediates the effect of cultural worldviews on epidemic policy support and whether the main effect of cultural worldviews and the mediating effect of government trust changes with risk perception. After reading the instructions, respondents completed the questionnaires.

Policy support was measured by public acceptance of 10 government policies from the early stage of the pandemic, such as “the government requires all residents to stay at home in order to control the epidemic.” All items were measured on a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The principal component analysis showed that when retaining one factor (59% of explained variance after rotation) that was obliquely rotated (PROMAX), higher scores reflected a higher likelihood of individuals supporting epidemic prevention policies (α = 0.92).

Government trust was measured by three items according to Gerber and Neeley, 2005. Representative items included “the authenticity of various information released by the government,” “the effectiveness of government measures to control the disease,” and “the degree of overall crisis control.” All items were measured on a 4-point scale from 1 (none) to 4 (very much). Principal component analysis showed that when retaining one factor (74% of explained variance after rotation) that was obliquely rotated (PROMAX), higher scores reflect the public having more confidence in the government (α = 0.82).

Cultural worldviews were measured on the revised scale in Study 1. All 12 items were separated by four factors and were measured on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). More details, such as mean and standard deviation, are presented in Table 2.

Risk perception was defined as the perception of the COVID-19 threat. It was measured based on the risk perception index developed by Leiserowitz (2003). Through the principal component analysis, it was found that two factors were obtained after the skew rotation. The first factor (42% of the explained variance after rotation) was related to the vulnerability of risk. It was evaluated by three questions, including “In general, how much risk do you think COVID-19 will pose to you personally?” (α = 0.72); The second factor (15% of the explained variance after rotation) was related to the severity of risk, evaluated by six questions, including “There will be further shortages in the supply of basic goods and health supplies such as masks and disinfectants.” (α = 0.81). All items were assessed on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (none) to 4 (very much). After calculating the two factors’ average scores, higher scores represented higher individual risk perceptions (α = 0.82).

For demographic characteristics, we included gender, age, education, and living area.

Data analysis and results

Description of demography variables

According to the description of 499 participants in the study, 61% of the participants are women as a whole, 70% are college graduates, 22% of the respondents have direct experience of the epidemic, 10% are from places where the epidemic was once high, and 12% of the respondents are from areas where the epidemic was high; The majority of respondents (75%) come from low-risk areas of the epidemic.

As presented inside the brackets and above the diagonal in Table 5, the trend of scores of cultural worldviews and correlations between policy support with cultural worldviews and risk perception was consistent with Study 3. Government trust was positively associated with policy support. There is a significant positive correlation between various cultural worldviews and a significant positive correlation between egalitarianism, individualism, and risk perception.

For hypothesis testing, we first centralized all variables except the demographic factors. Then, we analyzed the moderating and mediating effect using OLS regressions. As presented in Table 6, cultural worldviews and risk perception explained 25% of the variance in government trust. Hierarchy and egalitarianism were positively associated with government trust (β = 0.27, t = 4.73, p < 0.01; β = 0.16, t = 8.40, p < 0.01), whereas individualism was negatively associated with government trust (β = −0.09, t = −2.57, p < 0.05). Hypothesis 2 is, therefore, supported (except for Hypothesis 2d). Cultural worldviews and risk perception explained 19% of the variance in policy support. Hierarchy and egalitarianism were positively associated with pandemic prevention policy support (β = 0.06, t = 3.38, p < 0.001; β = 0.06, t = 3.59, p < 0.01), whereas individualism and fatalism were negatively associated with government trust (β = −0.05, t = −2.75, p < 0.01; β = −0.05, t = −2.79, p < 0.01).

As for the mediating effect of government trust, after government trust was added to model 5, the degree of explanation for policy support increased to 21%. Government trust positively predicted policy support (β = 0.09, t = 3.84, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the main effect of hierarchy on policy support was no longer significant (β = 0.03, t = 1.81, p = 0.07), indicating that government trust mediates the effect of hierarchy on policy support. The statistics of total effect (c), direct effect (c’), and indirect effect (ab) are as follows: c = 0.06, c’ = 0.03, ab = 0.02, the mediating effect is the proportion of indirect effect and total effect, that is, PM = ab/c = 0.33, the mediating effect accounts for 33% of the main effect. In addition, the influence coefficient of egalitarianism on policy support decreased from 0.06 (t = 3.59, p < 0.001) to 0.05 (t = 2.74, P < 0.01). The mediating effect of government trust accounted for 17% of the total effect of egalitarianism on policy support (c = 0.03, c’ = 1.81, ab = 0.01). The influence coefficient of individualism on policy support decreased from −0.05 (p < 0.01) to −0.04 (p < 0.05). The mediating effect of government trust accounted for 20% of the total effect of individualism on policy support (c = −0.05, c’ = −0.04, ab = −0.01). Therefore, hypotheses 1, 3, and 4 are supported (except for hypothesis 4d). In particular, a more hierarchical and egalitarian (and less individualistic) worldview leads to greater adherence to support epidemic prevention policies through increased trust in government.

As for the moderating effect of risk perception, after including the interactions between cultural worldviews and risk perception in the model of predicting government trust, the effect of the model was significant and explained 28% of the variance in government trust. The interaction between fatalism and risk perception positively predicted government trust (β = 0.18, t = 2.64, p < 0.01). The Johnson-Neyman method was used to analyze the moderating effect of risk perception. Figure 5 shows that compared to low-risk perception (that is, values lower than 0.50), government trust was more positively influenced by hierarchy under high-risk perception (β = 0.34, t = 9.17, p < 0.001). The effect of hierarchy on government trust in the context of low-risk perception was still significant (β = 0.15, t = 3.44, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 5a was partially supported. Nevertheless, the interaction terms between cultural worldviews and risk perception did not reach statistical significance, which means Hypothesis 5 was not supported.

Discussion

Study 4 examined the influence of cultural worldviews on epidemic prevention policy support and the role of risk perception and government trust in it. The results showed that (1) cultural worldviews significantly affected epidemic prevention policy support. Hierarchists and egalitarians are more likely to support government policies, and individualists and fatalists tend to oppose epidemic prevention policies. (2) Cultural worldviews significantly affected government trust, hierarchy, and egalitarianism (by positively predicting government trust), while individualism negatively predicts government trust. (3) Government trust played an intermediary role between cultural worldviews and policy support. (4) The positive effect of hierarchy on government trust is moderated by risk perception and increased with the public’s perceived threats.

Study 4 also found a significant positive correlation between various cultural worldviews and a significant positive correlation between egalitarianism, individualism, and risk perception. Most respondents (75%) in Study 4 came from low-risk areas of the epidemic. Although many studies have found that the objective risk indicator in the early stages of a pandemic is the distance from high-risk areas, the study also found that as cases gradually increase, the difference in the level of strict control across the country also decreases (English et al. 2022). The impact of place of residence on policy support may be smaller than the impact of cultural worldviews on policy support. In general, hierarchy has a stable main effect on policy support in Research 2, Research 3, and Research 4. Government trust mediates the main effect of hierarchy on policy support in Research 2 and Research 4.

General discussion

This paper systematically discussed the influence of cultural worldviews on attitudes toward mandatory policies, the mediating role of government trust, and the moderating role of risk perception through four studies. Study 1 showed that previous measurements of cultural worldviews, such as CTS and CCS, needed to be improved to apply to collectivist countries. Therefore, we conducted Study 1 to obtain a reliable and stable Cultural Worldview Scale. The revised cultural worldview scale with a reliability greater than 0.6 and stable validity for each subscale through exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. Furthermore, the positive effect of hierarchy on policy support was found by analyzing WVS data (Study 2) and epidemic survey data (Study 3–4). Government trust plays a mediating role in the relationship between hierarchy and policy support (Study 2), and the positive effect of hierarchy on policy support was stable and unaffected by risk perception (Study 4).

However, risk perception moderated the positive effect of hierarchy on government trust in the early stages of the epidemic. The positive predictive effect of hierarchy on government trust increased with the rise of risk perception (Study 4). Egalitarianism also significantly positively affected epidemic prevention policy support, and government trust played a mediating role in it (Study 4). Individualism and fatalism negatively predicted policy support (Study 3–4). However, fatalists will stop objecting to COVID-19 responses if they perceive a higher threat caused by the pandemic (Study 3) or start to trust the government (Study 4).

In conclusion, cultural worldviews can be used to explain the public’s attitudes towards mandatory policies in collectivist cultures, and the prediction effect and direction are consistent with those in the individualist culture; government trust also plays a mediating role in the effect of cultural worldviews on policy support, and the effect of cultural worldviews is stable and less affected by risk perception.

Cultural worldviews in collectivist culture

Previous studies have found that CTS and CCS show inapplicability in collectivist cultures such as South Korea, Mexico, and China (Dryhurst et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2016). The instability of the individualism dimension outside Western countries also shows that individualism is considered individual freedom in individualistic countries. However, in collectivist countries, individuals have a stronger sense of responsibility to the country, family, and community. In particular, individuals’ interdependent relationships with their families may make them suppress their desires to maintain their commitment to social norms (Bavel et al. 2020).

There are also differences between East and West in the collectivism dimension besides the individualism dimension. Western collectivism is based on an independent self-concept, which believes that groups are integrated by personalized parts, also known as “personalized collectivism”. However, collectivism in Asia is “we” based on the interdependent self-concept (Yang, 2015). Therefore, when studying cultural theory, one should consider the inherent cultural characteristics of the country in which they are located to expand the applicability of cultural worldviews. The inherent cultural characteristics of a country may indirectly affect its cultural worldview through the social exchange process between group members (Voorhees, 2022). Rice’s theories attempt to explain public behavior and attitudes from the perspectives of relationship mobility and strict social norms. Relationship mobility refers to the degree to which society can form new relationships, and the similarity between the concept of “group” emphasizes the degree to which individuals are constrained by their group. Strict social norms are accompanied by strict rules, similar to the concept of “lattice” that emphasizes the individual’s constraints by order. The research results also found that societies with a history of rice cultivation have stricter social norms and lower relationship mobility (Talhelm et al. 2022), and in China’s group studies, Chai et al. (2009) found that Chinese people belong to the cultural tendency of high-grid and high-group. The above discussion further demonstrates the significance of applying a cultural worldview to explore Chinese social issues in the context of Chinese culture.

Although the study found that it is feasible to use cultural theory to analyze the differences in public attitudes and behaviors in China, the study also found that the correlation between cultural worldviews in a collectivist culture needs to be clarified. We found that hierarchy, egalitarianism, individualism, and fatalism are significantly positively correlated, consistent with previous studies (Xue et al. 2016; Johnson and Swedlow, 2019a; Kim and Kim, 2019; Chen et al. 2020). Only one study has found a negative correlation between hierarchy and individualism (Rippl, 2002). It is challenging to separate hierarchy and individualism. One possible reason is that hierarchy and individualism support social stratification and competition (Kiss et al. 2016). That is, they encourage economic competition and tend to maintain social order (Johnson and Swedlow, 2019a). We also found that individualism and fatalism negatively predict government trust, so individualism and fatalism may be closer to each other regarding the tendency to question authority. However, due to the random response caused by fatalism’s resigned attitude, fatalism’s attitude towards authority may be affected by the perception of the current situation (Verweij et al. 2011). We also found that there is a correlation between egalitarianism and hierarchy. Previous research found that hierarchy and egalitarianism dominate China (Yin et al. 2014; Zeng et al. 2020; Bi et al. 2021). Egalitarianism and hierarchy both belong to a high group tendency. Maintaining order and pursuing equal relationships in China are means of integrating into the group through established rules and systems. Everyone works together to develop in a better direction. In organized environmentalist surveys, Grendstad and Selle (2000) found that most people can hold both a hierarchical view of nature and an equal view of human nature when considering environmental issues. Hierarchy and egalitarianism are more likely to be values with a high sense of responsibility. For example, studies found that in the early stages of COVID-19 in the United States and Europe, regions with a high sense of responsibility are more likely to maintain social distancing voluntarily and, thus, more likely to support national policies that effectively control current threats (Barbieri and Bonini, 2021).

Influence of cultural worldview on epidemic prevention policy support

Cultural theory is proposed to explain the differences in public policy support from values and beliefs about how society is constructed (Swedlow, 2011). Through the four studies, we found that cultural worldviews can predict the attitude towards mandatory policies in the Chinese public, with hierarchists tending to support government policies no matter under what circumstances (Song et al. 2014), and hierarchists are also more inclined to believe in government policies and propositions due to their habitual trust in the government. Biddlestone et al. (2020) found that when individuals believe they are in an unequal position, they are more reluctant to support social isolation policies regardless of feeling helpless about the status quo. This finding was confirmed in our studies that showed that individualists are less likely to trust the government and less likely to support mandatory policies. The negative effect of fatalism on public attitudes towards COVID-19 responses is also known as the “fatalism effect.” Fatalists view infectious disease as a matter of fate or luck, so when fatalists believe they are destined to be infected, they have more possibility not to comply with policies (Akesson et al. 2020).

Moreover, although cultural worldview is a distant variable, it substantially impacts policy attitudes more than subjective norms, which are social constraints on individual behavior. The effect of individualism on public attitudes towards mandatory policies is more substantial than that caused by subjective norms (Wang, 2022). Therefore, cultural worldviews are still influential in predicting Chinese public attitudes toward government policies. Its relationship with power institutions can explain the relationship between cultural worldviews and policy support. Cultural worldviews are unrelated to a specific social or political identity (such as a country, an international organization, or an interest group) (Song et al. 2014). Cultural worldviews are unrelated to a specific social or political identity (such as a country, an international organization, or an interest group) (Song et al. 2014). The influence of cultural worldviews on policy support is related to the recognition of the policy proposer. Therefore, determining the agency mechanisms and boundary conditions of cultural worldviews on policy support is an essential field of research on cultural theory (Verweij et al. 2011).

Firstly, a cultural worldview can predict risk perception in a way consistent with an individual’s preferred worldview. We found that egalitarianism and individualism tend to prioritize the current health threat of the epidemic, which is consistent with previous studies (Kahan et al. 2007; Weaver et al. 2017). However, early studies in America found that the hierarchists tend to be skeptical of social and health risks that require more government regulation (Chen et al. 2020; Kahan et al. 2010), which is contrary to our findings. It is because American hierarchists are more likely to weigh personal interests than social or national ones, which also differs from China’s hierarchy. Xie et al. (2003) found that the Chinese public is more concerned about risks that threaten national stability and family welfare than personal threats. Nevertheless, the Western public is most concerned about accident risks, followed by disease and natural and technological hazards (Fischer et al. 1991). Risk perception can also impact public attitudes and behaviors. We analyzed specifically whether risk perception can mediate the effect of cultural worldviews on policy support 2. Through additional analysis, we found that risk perception can mediate the impact of egalitarianism and hierarchy on policy support. However, government trust is a better mediator variable in explaining the differences in policy support among different cultural worldviews. We did not find a correlation between government trust and risk perception, which is consistent with the situation found by Chen et al.(2020).

The mesomeric effect of risk perception is not stable, which also supports our model. Our research also found that although fatalism can negatively predict mandatory policy support, fatalists may stop opposing government COVID-19 responses when they think they are in high-risk situations. Meanwhile, the positive effect of hierarchy on policy support is not affected by risk perception, indicating the existence of a dominant cultural worldview in crises, which largely determines public policy support.

Enlightenment from epidemic prevention practices

The COVID-19 epidemic is a long-term battle, and governments have responded in ways that range from social distancing and health advice (as in Sweden) to total blockades of movement (as in Italy). Policies’ success in slowing the spread of COVID-19 depends on individuals’ implementation of epidemic prevention policies (Reluga, 2010; Bavel et al. 2020). Lu et al.(2021) found that when people put the collective in the first place, they can better contain the spread of epidemics, and when people pay more attention to “us” instead of “me,” individuals’ willingness to comply with epidemic prevention policies might increase. However, Falco and Zaccagni (2020) have found that people can only respond when faced with information emphasizing the impact on respondents and their families. They do not care about information that affects the country and society. We also found that hierarchy and egalitarianism are more likely to support national policies. Therefore, in the face of emerging threats, what kind of information will be more effective in risk communication is worth further study.

Meanwhile, public cooperation in epidemic prevention policies also depends on trust in the state and society to reduce the burden on national health institutions. Trust also means vigilance against a crisis and optimism about the prospects of its resolution. Respondents who followed the government’s epidemic prevention measures had a high degree of trust in health organizations (Prati et al. 2011). The public’s distrust of society and institutions would also translate into suspicion towards medical treatment and vaccines (Bogart et al. 2021). Therefore, establishing trust between individuals and authorities is also essential to effective epidemic prevention and control. However, an epidemic study in Singapore shows that high government trust would also make individuals lose their vigilance and fail to comply with preventive measures (Wong and Jensen, 2020). Based on this context, how to establish trust between the government and the public while also keeping the public alert to the rebound of the epidemic is another topic in long-term crisis management.

Limitations, and suggestions for future research

We explored the relationship between cultural worldviews and policy support in collectivist culture and explained the influence of government trust and risk perception. This research also has some limitations.

Firstly, although we have obtained a four-dimensional scale by revising the Cultural Theory Scale, the revised scale only applies to studying Chinese culture. Further research is needed to replicate it in other social and political backgrounds and countries and determine whether cultural worldviews will directly influence policy support. In subsequent research, the convergence validity of each worldview should also be considered (the degree of correlation with the corresponding worldview dimension in another worldview scale with good reliability and validity). Although this study examined the impact of cultural worldviews on epidemic policy support, future studies can also explore the predictive validity of each worldview (targeting specific national policies in specific fields). Secondly, the study explores the role of cultural worldviews through a horizontal research approach. However, the causal effects of cultural worldviews on policy support derived from relevant research should be cautious. Risk perception, as a situational factor, can be analyzed through longitudinal studies or experiments to determine whether the effects of cultural worldviews on epidemic prevention policy support will change under different risk conditions. Then, we discussed the relationship between individuals and organizations - the mediating role of government trust in the effect of cultural worldviews on policy support. So, the mediating effect of other relational variables, such as power distance, can be explored in the subsequent research to improve the theoretical mechanisms underpinning the application of the Cultural theory in collectivist countries. Thirdly, this data was collected during the first year of the pandemic, and subsequent changes in zero-covid strategy might yield different patterns of results, especially during a strict snap-lockdown phase like in Shanghai. Unfortunately, the data cannot corroborate these changes. Finally, it is meaningful to discuss under what circumstances a cultural worldview expresses views consistent with its value orientation and whether it can be triggered through clues to demonstrate a policy attitude consistent with its worldview. Explaining the public’s attitude towards current events and politics through cultural theory can better explain the cultural significance behind the public’s expression of their views, which is of great significance to cross-cultural studies and cultural theory in other environments.

Conclusion

The current research revealed the impact mechanism of cultural worldview on the support for governmental management of the Chinese public. This novel finding complements previous research by highlighting that government trust served as a mediator in the effect of cultural worldviews on policy support and that the negative effect of fatalism on epidemic prevention policy support disappeared in the context of high-risk perception. In contrast, the positive effect of hierarchy on government trust increased under high-risk conditions.

Note 1: We conducted regression analysis using cultural worldviews and risk perception as independent and dependent variables and found that egalitarianism (β = 0.24, p < 0.001) and fatalism (β = 0.14, p < 0.05) significantly positively predicted risk perception. After controlling demographic variables such as gender and age, egalitarianism and fatalism still positively predict risk perception and hierarchy’s positive predictive effect on risk perception begins to be significant (β = 0.13, p < 0.05).

Note 2: The anonymous reviewer mentioned that risk perception might mediate the influence of cultural worldviews on policy support. Therefore, in our research, we also designated cultural worldviews and policy support as independent and dependent variables and risk perception and government trust as intermediary variables to conduct process regression analysis from this perspective. First of all, we find that in study 3, risk perception has the most potent mesomeric effect of egalitarianism on policy support (Effect = 0.05, 95% CIs [0.01, 0.10]); Secondly, the mesomeric effect of risk perception in the impact of fatalism on policy support is (Effect = 0.04, 95% CIs [0.01,0.08]); In hierarchy and individualism, the mesomeric effect of risk perception is (Effect = 0.03, 95% CIs [0.004, 0.02]) and (Effect = 0.03, 95% CIs [0.001, 0.07]), respectively, so risk perception plays a mediating role in the impact of cultural worldview on policy support; In further study 4, the study found that risk perception can play a mediating role in the influence of egalitarianism and hierarchism on policy support, and the mesomeric effect is (Effect = 0.01, 95% CIs [0.002, 0.02]) and (Effect = 0.01, 95% CIs [0.001, 0.02]). For fatalism and individualism, the mesomeric effect of risk perception is insignificant, and the mediating role of government trust and risk perception in the cultural worldview’s policy support effect is not established.

Data availability

We deposited the data and code for analyses at the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/3stm9/.

References

Akesson, J, Ashworth-Hayes, S, Hahn, R, Metcalfe, RD, & Rasooly, I (2020). Fatalism, beliefs, and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic (No. w27245). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper No. 27245, May

Bachem R, Tsur N, Levin Y, Abu-Raiya H, Maercker A (2020) Negative affect, fatalism, and perceived institutional betrayal in times of the coronavirus pandemic: a cross-cultural investigation of control beliefs. Front Psychiatry 11:589914

Barbieri PN, Bonini B (2021) Political orientation and adherence to social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Econ politica (Bologna, Italy) 38(2):483–504

Baumgaertner B, Carlisle JE, Justwan F (2018) The influence of political ideology and trust on willingness to vaccinate. PloS One 13(1):e0191728

Bavel J, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A et al. (2020) Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behaviour 4(5):460–471

Bi X, Zhang Q, Fan K, Tang S, Guan H, Gao X, Cui Y, Ma Y, Wu Q, Hao Y, Ning N, Liu C (2021) Risk culture and COVID-19 protective behaviors: a cross-sectional survey of residents in China. Front Public Health 9:686705

Biddlestone M, Green R, Douglas KM (2020) Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br J Soc Psychol 59(3):663–673

Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, Klein DJ, Mutchler MG, Dong L, Lawrence SJ, Thomas DR, Kellman S(2021) COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among black americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 86(2):200–207

Bordat-Chauvin, Elodie (2016) Cultural policies and change: mexico and argentina after the neoliberal turn (1983–2012): cultural policies and change. Lat Am Policy 7(1):147–162

Bostrom A, Hayes AL, Crosman KM (2019) Efficacy, action, and support for reducing climate change risks. Risk Anal 9(4):805–828

Caulkins D (1999) Is Mary Douglas’s grid/group analysis useful for cross-cultural research? Cross-Cult Res 33:108–128

Chai SK, Ming L, Kim MS (2009) Cultural comparisons of beliefs and values: applying the grid-group approach to the world values survey. Beliefs & Values 1(2):193–208

Chauvin B, Chassang I (2022) Cultural orientation and risk perception: development of a scale operating in a french context. Risk Anal 42(10):2189–2213