Abstract

Radical innovation is necessary for firms to transform existing markets or create new ones, which has critical impact on firm performance. Therefore, there is a need to explore how radical innovation can be successfully achieved. Entrepreneurial orientation reflects a firm’s willingness to be innovative, proactive and risk-taking, which has been recognized as a key factor contributing to firm innovation. However, the specific focus on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is very limited. This paper therefore investigates how entrepreneurial orientation affects radical innovation by considering the contingency effects of board characteristics. Using the panel data of listed manufacturing firms in China from 2013 to 2019, this paper found that entrepreneurial orientation has a significant positive impact on radical innovation. Furthermore, different board characteristics play asymmetric moderating roles in that relationship in such a way that CEO duality and board independence play positive moderating roles, while board ownership and board size play negative moderating roles. This paper contributes to the entrepreneurial orientation literature by providing a finer-grained understanding of the role of entrepreneurial orientation on radical innovation. This paper also contributes to the corporate governance literature by revealing the asymmetric contingency effects of different board characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, more and more research has attempted to explore how to achieve radical innovation, as it always involves significant technological advances that can create technologies that have the potential to fundamentally change technological trajectories (Brasil et al. 2021; Sandberg and Aarikka-Stenroos, 2014). Therefore, radical innovation is of critical importance for firms to gain first-mover advantage (Forés and Camisón, 2016). However, the failure rate of radical innovation is also particularly high due to its various challenges, so there is still a need to explore how radical innovation can be successfully achieved (Rampa and Agogué, 2021).

Radical innovation can be defined as the significant departures from a firm’s existing technological trajectory, which requires greater efforts of the firms (O’Connor and Rice, 2013). The existing research suggests that there are several kinds of drivers of radical innovation, such as organizational capabilities (Chang et al. 2012; Freixanet and Rialp, 2022), firm knowledge (Forés and Camisón, 2016; Zhou and Li, 2012), leadership styles (Domínguez-Escrig et al. 2019), and strategic orientations (Kocak et al. 2017; Sainio et al. 2012). Among these drivers, entrepreneurial orientation stands out (Eshima and Anderson, 2017). Entrepreneurial orientation reflects a firm’s willingness to be innovative, proactive and risk-taking (Anderson et al. 2015; Miller, 1983), which has been recognized as a key factor contributing to firm innovation (Pérez-Luño et al. 2011). Despite the abundance of studies on entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation, the specific focus on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is very limited (Ato Sarsah et al. 2020; Salavou and Lioukas, 2003). In today’s competitive environment, a firm’s survival and expansion is strongly dependent on radical innovation (Chirico et al. 2022). Therefore, the key issue is to understand how to achieve successful radical innovation. Following this research trend, this paper focuses on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, which can provide new insights into how to give rise to radical innovation.

Furthermore, the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation may not be as straightforward as assumed. It has been argued that in order to achieve radical innovation, firms must not only rely on entrepreneurial orientation, but also translate this orientation into innovation (Saeedikiya et al. 2021). While entrepreneurial orientation provides significant motivation to pursue innovation, effective transformation of entrepreneurial orientation requires leadership support (Engelen et al. 2015). Following this logic, previous research has examined the role of top management leadership on the effect of entrepreneurial orientation (Engelen et al. 2015; Palmer et al. 2019). Although research on corporate governance has considered top management leadership as the decisive force in guiding entrepreneurial orientation, a firm’s board also typically plays an important role (Arzubiaga et al. 2018). Radical innovation is highly risk that needs to be carefully managed. Under such condition, a firm’s board is particularly important as it is an important corporate governance mechanism to avoid agency problems in radical innovation (Cortes and Herrmann, 2021). A firm’s board is usually directly involved in making and implementing a firm’s strategic decisions (Desai, 2016; Ruigrok and Peck, 2006), and it also involves critical activities, such as providing access to valuable resources (Zona et al. 2013). Therefore, a firm’s board can significantly influence the extent to which a firm employ entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation. However, virtually less research to date has examined how a firm’s board affects the link between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. This is an important omission, as it may result in firms failing to reap greater benefits from entrepreneurial orientation. Recent research has acknowledged the complexity of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation (Ferreras-Méndez et al. 2022). It has been argued that the research on entrepreneurial orientation would benefit from testing potential moderators, as the effect of entrepreneurial orientation is likely to vary across contexts. This paper therefore examines how board characteristics affect the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, which can add much to the understanding of the heterogeneity of entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Building on corporate governance theory, this paper develops a research model to explicate which kind of board benefits more from the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. Using the sample of listed manufacturing firms in China from 2013 to 2019, the results show that entrepreneurial orientation has an important impact on radical innovation. The results also show that different board characteristics play asymmetric moderating roles. To be specific, CEO duality and board independence play positive moderating roles, while board ownership and board size play negative moderating roles.

This paper provides greater insights about the current research. Firstly, although previous research has analyzed the effect of entrepreneurial orientation on firm innovation, the link between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation has been less frequently analyzed. This paper tackles the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation directly, which is essential to know which kind of strategic orientations firms should concentrate on to achieve radical innovation. Secondly, as a major theoretical contribution, this paper advances the research on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation by adding a new contingency perspective, namely corporate governance perspective. Previous studies have investigated how external factors affect the effect of entrepreneurial orientation, but limited research has focused on internal factors that may affect the transformation of entrepreneurial orientation (Engelen et al. 2015). This paper reveals that the role of a firm’s board in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, which may help explain why some firms are more entrepreneurial. Thirdly, this paper advances a more complete understanding of how a firm’s board contributes to the transformation of entrepreneurial orientation by taking into multiple board characteristics into consideration, which provides a more complete view of the role of a firm’s board from a configuration perspective.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section “Theoretical development and hypotheses” proposes the theoretical framework and the research hypotheses for the asymmetric roles of board characteristics in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. The method issues are described in Section “Method”, and the research results are presented in Section “Results”. Section “Discussion” discusses the research results and theoretical contributions. The final section provides practical implications and limitations and future research.

Theoretical development and hypotheses

Theoretical framework

Entrepreneurial orientation has been extensively studied in the literature. It is argued that entrepreneurial orientation has three core dimensions, which are innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking (Lomberg et al. 2017). Innovativeness reflects a firm’s tendency to take part in creative processes. Proactiveness reflects a firm’s willingness to search for new opportunities. Risk-taking involves the desire to commit significant resources into the unknown area in which the outcome may be highly uncertain. Therefore, an entrepreneurial orientation firm is one that actively participates in creating new technologies, is more proactive than its competitors, and undertakes business strategies with high risks (Covin and Lumpkin, 2011). Entrepreneurial orientation thus provides a favorable setting for firms to achieve innovation (Wales et al. 2020), which could affect firm innovation performance (Dana et al. 2022).

However, it has been shown that not all firms benefit equally from entrepreneurial orientation (Arzubiaga et al. 2018; Saeedikiya and Aeeni, 2020). Therefore, in order to predict the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation more effectively, the contingency perspective should be considered (Covin and Wales, 2019). Radical innovation is one of the main organizational strategies to respond and adapt to environmental changes (Salamzadeh et al. 2022; Tajpour et al. 2020), while entrepreneurial orientation determines the firm’s strategy behavior (Li et al. 2023). Since entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation are both related to a firm’s strategy, the integration of entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation must originate from a firm’s strategic decisions (Arzubiaga et al. 2018). Research on corporate governance has viewed it as the decisive force for a firm’s strategic decisions (Honoré et al. 2015). Therefore, corporate governance is one of the main determinants of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. Following this logic, corporate governance has been used as a key contextual factor to investigate whether it can enhance or constrain the impact of entrepreneurial orientation (Engelen et al. 2015; Palmer et al. 2019).

To explain how entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation spread within a firm, corporate governance is an essential perspective (Yazdanpanah et al. 2023). Corporate governance is a set of mechanisms that reconcile the conflicting interests between managers and shareholders arising from the separation of control and ownership (Honoré et al. 2015). Radical innovation is risky with high uncertainty, which requires corporate governance to avoid opportunistic behavior (Sapra et al. 2014). Corporate governance can help firms to have a degree of certainty against the risk and uncertainty of radical innovation. While scholars have considered to explore the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation from the corporate governance perspective, the role of the board has been largely neglected (Arzubiaga et al. 2018). It is argued that a firm’s board is the main vehicle for corporate governance because it is the body that makes decisions on major corporate issues (Adams et al. 2010). Corporate governance research has shown that a firm’s board is the most important measures for overseeing the management, which can be an important means of mitigating agency problems and encouraging managers to act properly (Gillan, 2006). It can therefore be argued that, from corporate governance perspective, a firm’s board is a key context for the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

From the corporate governance perspective, the integration of a firm’s board as a moderator of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is guided by two main reasons (Cumming and Leung, 2021). On one hand, a firm’s board is involved in making a firm’s strategic decisions directly (Wu and Wu, 2014), which are useful in increasing or decreasing the returns of entrepreneurial orientation. On the other hand, a firm’s board can help the firm to access the necessary resources (Chang and Wu, 2021), and thus it can act as the primary resource provider for the implementation of strategy decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. Therefore, a firm’s board may significantly influence the effect of entrepreneurial orientation.

However, so far, the literature has provided limited evidence on the role of a firm’s board on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. By disentangling how the different board characteristics, namely CEO duality, board independence, board ownership and board size, may facilitate or hamper the transformation of entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation, this paper could provide important insights on how entrepreneurial orientation should be managed, and also call for further research on the other contingencies of the entrepreneurial orientation-radical innovation relationship.

Entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation

This paper proposes that entrepreneurial orientation may have a positive relationship with radical innovation, and it develops the theoretical arguments from the three dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation.

Innovativeness as a dimension of entrepreneurial orientation could encourage firms to renew their existing domains and to enter new domains (Szymanski et al. 2007), which could provide the predisposition to engage in radical innovation. It is argued that firms with high innovativeness will generate a strong willingness to depart from existing practices and engage in exploratory experiments (Hult et al. 2004). These exploratory experiments may give rise to radical innovation. Furthermore, firms that are characterized by innovativeness can also attract more creative employees (Kyrgidou and Spyropoulou, 2013), which could stimulate higher levels of organizational creativity (Rauch et al. 2009). Therefore, innovativeness firms may also accumulate a broader and deeper knowledge base that they can use to achieve radical innovation.

Proactiveness as a dimension of entrepreneurial orientation suggests the characteristic of being forward-looking towards the market (Putniņš and Sauka, 2020). With such a proactive mind, firms may have more desires to be pioneers, and thereby they may capitalize on opportunities to achieve radical innovation (Hughes et al. 2021). On one hand, by scanning through the environment to search for useful information, proactive firms can make better use of available opportunities to satisfy underserved markets (Lumpkin and Dess, 2001). Therefore, firms with high levels of proactiveness will be in a favorable position to develop radical innovation because their competitors may not yet have identified these available opportunities. On the other hand, proactive firms are also willing to create new markets by guiding consumers to form new demands (Hughes and Morgan, 2007). In doing so, firms that display high levels of proactiveness will build their capabilities to introduce new technologies (Pérez-Luño et al. 2011), which has significant impact on radical innovation.

Risk-taking is associated with the willingness to invest resources into the projects with high failure rates (Rank and Strenge, 2018). Radical innovation is fundamentally risky and unless a firm is willing to face failure, it will refrain from such activities. Therefore, risk-taking may generate a basis for firms to engage in radical innovation. In contrast, without risk-taking, firms may be unwilling to engage in such risky activities, which may result in less radical innovation. Moreover, radical innovation is a process with steep learning curves. Risk-taking encourages firms to do things in new ways (Pérez-Luño et al. 2011), and such an approach may help firms accumulate more knowledge for radical innovation. On the contrary, firms with low level of risk-taking may be inertia and inaction, which are likely to deteriorate radical innovation. Based on the arguments above, this paper proposes the baseline hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Entrepreneurial orientation is positively associated with radical innovation.

Moderating roles of board characteristics

Moderating role of CEO duality

CEO duality means that the CEO and the chairman of the board in a firm are held by the same person. It is argued that CEO duality may have a positive effect in some conditions, such as high complexity (Boyd, 1995). Entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation are all have a high degree of complexity, and thus CEO duality may facilitate entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation.

Firstly, the CEO with duality has less pressure to ensure short-term financial performance (Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia, 1998), and therefore such a firm is more likely to adopt entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation. When the CEO is non-duality, he/she always has more difficult performance tasks to accomplish (Wiseman and Gomez-Mejia, 1998). In such circumstance, the CEO is under greater pressure, and has less intention to employ entrepreneurial orientation to develop radical innovation because it cannot produce a controllable short-term financial performance. In contrast, the CEO with duality is less burdened by meeting short-term financial goals. In such circumstance, the dual CEO, with a broader power base and locus of control, could have more freedom in making strategic decisions related to entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. This could facilitate entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation, which is less predictable but has the potential to generate high returns in the near future.

Secondly, CEO duality could establish a strong and unambiguous leadership (Tang, 2017), which may enable the implementation of strategic decisions of transforming entrepreneurial orientation to radical innovation. CEO duality establishes a unified leadership (Peng et al. 2010). Therefore, when CEOs chair the board, they have more discretion to enable the implementation of strategic decisions. This may speed up the transformation from entrepreneurial orientation to radical innovation, especially in a dynamic business environment (Wang et al. 2019). In addition, it is suggested that the CEO as the chairman of the board can improve the communication between the management team and the board (Krause et al. 2014). This is also beneficial for a firm to implement its entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation, as the better communication can help firms to implement entrepreneurial orientation in a more timely manner. In contrast, the CEO without duality may have limited freedom (Ramdani and Witteloostuijn, 2010). Therefore, he/she cannot implement his/her strategic decisions freely, and he/she may also need additional time and effort. This is not conducive to the transformation of entrepreneurial orientation to radical innovation. Based on the arguments above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: CEO duality moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, such that the relationship is more positive when CEO has duality than when CEO does not have duality.

Moderating role of board independence

A board with more independent directors is more independent. One of the important functions of independent directors for firms is the provision of resources, such as human capital and relational capital (Hillman and Dalziel, 2003). These are important for firms to overcome the problems in employing entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radial innovation. Accordingly, board independence may play a significant moderating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Firstly, the human capital of independent directors can be a source of support in making strategic decisions related to entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. It is believed that the groups with similar backgrounds are more likely to fall into narrow perspectives (Kim et al. 2009). As a result, a firm’s board with more inside directors who have relatively homogeneous backgrounds may produce faulty strategic decisions (Ben Rejeb et al. 2020). On the contrary, a firm’s board with a higher proportion of independent directors are more likely to be heterogeneous, as different independent directors may have different backgrounds (Boivie et al. 2016). What’s more, independent directors always have rich experiences and skills that can be provided for advice (Lu and Wang, 2018). Such kind of board may incorporate more diverse perspectives, which may contribute to form strategic decisions related to entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Secondly, the relational capital of independent directors can also be a source of support in the implementation of strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. Independent directors are more likely to have their own networks, which can help firms to acquire resources from outside to implement entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation (Chen, 2011). On one hand, the social ties of independent directors may help firms to establish valuable connections with external stakeholders to access to the necessary financial resources and human resources (Chen et al. 2016). Therefore, the increased use of independent directors may help firms to become more capable in implementing entrepreneurial orientation, consequently, to undertake costly radical innovations. On the other hand, independent directors with strong networks are also helpful in acquiring information and knowledge about how other firms implement entrepreneurial orientation (Wincent et al. 2009). Accordingly, the increased use of independent directors could help firms to draw on the experience of others to be more effective in implementing entrepreneurial orientation, which in turn increases radical innovation. Based on the arguments above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: Board independence moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, such that the greater the board independence, the more positive the relationship.

Moderating role of board ownership

Board ownership has been identified as an important indicator that may affect the behavior of a firm’s board. High board ownership may align the economic wealth of the directors with the value of the firm, which can encourage them to be more active. However, a firm’s board with high ownership may also lead to more strategic intervention, which may negatively affect the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Firstly, the strategic intervention brought by the high level of board ownership may not be beneficial for firms making risky decisions, which is detrimental to strategic decisions related to entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. High level of board ownership means that directors may suffer more risk in their investment. If their investments fail, it will bring them wealth shrink. Therefore, directors with higher ownership may become increasingly shortsighted so that they will manage the firm to obtain short-term benefits rather than long-term value (Oh et al. 2011). In such circumstance, firms have less possibility to make strategic decisions related to entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, which are high risk.

Secondly, the strategic interventions brought by the high level of board ownership may also not be beneficial for the implementation of strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. Board ownership is an important source of power, which would allow directors to act in their own self-interest without fear of being removed or sanctioned (Hernández-Lara et al. 2014). When directors obtain relatively large ownership, they will have sufficient power to transfer firm resources for their own ends in the way that may be harmful to maximize firm value (Farrer and Ramsay, 1998). In such circumstance, resources that should be supported to the implementation of strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation will be wasted. Alternatively, directors that hold less percentage of ownership may have fewer controls, which may result in firms having more resources to implement strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. Based on the arguments above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Board ownership moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, such that the greater the board ownership, the less positive the relationship.

Moderating role of board size

Board size is also an important board characteristic. Previous research has indicated that larger board is always accompanied with a good deal of coordination costs (Zona et al. 2013). As a consequence, larger boards are more likely to be slower in strategic decisions making and strategic decisions implementation, which may prevent firms from getting more benefits from entrepreneurial orientation.

Firstly, a group’s decision is usually a compromise that contains different opinions of the members (Cheng, 2008). However, reaching a compromise becomes especially difficult in a larger board because when the board size increases, coordination among different directors becomes more complex (Akbar et al. 2017). The coordination problems may come from a number of sources, such as it is hard for larger boards to hold meetings on time; higher diversity of perspectives leads to conflict among the directors; the communication among directors might be more formal and informal methods are less effective. Since entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation both count on the strategic decisions of the board, these coordination problems with larger board size make firms difficult to make strategic decisions related to entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Secondly, larger board size may make individual directors difficult to contribute their knowledge and skills about how to implement the strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. On one hand, in larger boards, individual directors may feel less motivated because the relatively low impact of their personal contributions on the group outcomes (Ahmed et al. 2006). In such case, firms with larger boards suffer from the problem of diffusion of responsibility, which is not conducive for firms to implement the strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. On the other hand, individual directors in larger boards are less likely to function effectively because they may find that advocating a prudent alternative is unlikely to be met with stern opposition (Nakano and Nguyen, 2012). It thus follows that larger boards may decrease firms’ propensity to take risks, which impedes the implement the strategic decisions to transform entrepreneurial orientation into radical innovation. Based on the arguments above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5: Board size moderates the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, such that the greater the board size, the less positive the relationship.

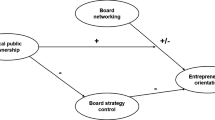

Figure 1 depicts the relationships among the variables proposed in the hypotheses.

Method

Samples

The data used to test the proposed hypotheses were obtained from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, Wind database, and Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS) database. In detail, this paper obtained dependent variable (radical innovation) data from CSMAR database and CNRDS database. The independent variable (entrepreneurial orientation) data, moderating variables (board characteristics) and control variables data were obtained from the CSMAR database. The missing data was searched from Wind database. In the initial sample, this paper included all the manufacturing firms listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2013 to 2019. Then, this paper excluded the firms with special treatment (ST and ST*), the firms with abnormal data, and the firms with incomplete information. After these procedures, the final dataset can be used in this paper had 10500 firms-observations representing 1620 firms. To avoid the potential influence of extreme observations, this paper winsorized the top 1% and bottom 1% of each variable.

Measurement

Dependent variable

In previous research, patent applications have been a commonly used measure of innovation output. This measurement has at least the following two advantages. Firstly, the patent applications can be rapidly derived from R&D activities. Therefore, the patent applications can reflect the innovation output directly. Secondly, patent applications could represent more management efforts, while patent granted could be the results of management efforts and it also can be the results of government regulations (Wu et al. 2005). In this paper, we focus on the results of entrepreneurial orientation and therefore patent applications are considered more appropriate than patent granted (Wang et al. 2016).

Generally, there are three types of patents in China, which are invention patents, utility patents and design patents. Among these three types of patents, invention patents are argued to be the most original because they have the highest requirements of inventiveness (Rong et al. 2017). On the contrary, utility patents or design patents only require the patent application has not previously been granted. Therefore, following previous research (Yuan and Wen, 2018), this paper measures radical innovation by the natural logarithm of the number of invention patent applications in one year plus one. In this paper, the dependent variable (radical innovation) is one year lag than the independent variables (entrepreneurial orientation and board characteristics).

Independent variable

The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation is referred to the research of Williams and Lee (2009). Williams and Lee (2009) argued that the entrepreneurial orientation of a firm can be divided into two directions. The first direction emphasizes the technology development for the long-term, and the second direction emphasizes the asset growth for the short-term. Following their research (Williams and Lee, 2009), the first direction can be measured by the ratio of R&D investment to sales revenue, and the second direction can be measured by the ratio of the firm’s annual investment activities net cash flows to sales revenue. Those two directions could form four kinds of combinations, and the different points reflect the different status of entrepreneurial orientation. According to their research (Williams and Lee, 2009), entrepreneurial orientation thus can be calculated by:

Where, xit represents the ratio of R&D investment to sales revenue of the firm i in year t. yit represents the ratio of the firm’s annual investment activities net cash flows to sales revenue of the firm i in year t. Entrepreneurial orientationit represents the entrepreneurial orientation of the firm i in year t. The smaller values indicate the lower of entrepreneurial orientation, and the greater values mean the higher of entrepreneurial orientation. This measurement has been used in many other studies, such as Yang and Wang (2014).

Moderating variables

In line with previous research (Peng and Fang, 2010; Ruigrok et al. 2006), a dummy variable was created to measure CEO duality, with the value 1 if the CEO is also the chairman of the board and 0 otherwise. Board independence was measured by the percentage of independent directors to all directors. Board ownership was measured by the shareholding of directors as a percentage of all shares. Board size was measured by the number of directors within a board.

Control variables

Following previous research, this paper incorporated a set of control variables to avoid the spurious relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. Firm size and firm age were included because larger firms and older firms may possess more resources for firm innovation (Petruzzelli et al. 2018). According to previous research, firm size is measured by the natural log of the total assets (Munjal et al. 2019), while firm age is measured by the number of years it established (Carr et al. 2010). Firm growth was chosen because a firm with more growth opportunities naturally is more innovative (Chi et al. 2019). The firm growth is measured by the percentage annual growth of sales (Choi et al. 2011). State ownership was chosen because state ownership is an optimal structure for innovation development (Zhou et al. 2017). A dummy variable is used to measure state ownership by 1 if a firm’s ultimate controller is the state, and 0 is otherwise (Li et al. 2019). For the sake of considering the effect of debt to equity ratio on innovation investment, this paper included leverage, measured by the ratio of the book value of debt to total assets, as a control variable (Jiang et al. 2020). In order to consider the effect of ownership structure on firm innovation, this paper included ownership concentration, measured by the ownership held by the top three largest shareholders, as a control variable (Choi et al. 2012). This paper also created industry dummy variables and year dummy variables to account for industry effects and year effects.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the dependent variable, independent variable, moderating variables and control variables. From Table 1, it can be seen that the value of radical innovation ranges from 0.000 to 3.989, indicating that there exists significant variations in radical innovation. The mean value of entrepreneurial orientation is 0.157, indicating that the entrepreneurial orientation of sample firms is relatively low.

Table 2 presents the correlation coefficients between all the variables in this paper. From Table 2, the correlation coefficient between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is 0.0201 (p < 0.1). The positive and significant correlation coefficient indicates that the more entrepreneurial orientation, the more radical innovation. This result is consistent with the Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, the results show that the correlation coefficients between different independent variables are not too high to raise the concern of multicollinearity.

Regression analysis

This paper ran multiple hierarchical regression with Stata 15.0 to test the proposed hypotheses. Following the common procedure, the independent variable and moderating variables were mean-centered in order to reduce the potential problem of multicollinearity. This paper uses Hausman test to choose the fixed effect model or random effect model, and the results show that the fixed effect model is better. Therefore, following previous research (Chi et al. 2019; He et al. 2020), this paper used the fixed effect model in the regression analysis. Model 1 examines the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, and the coefficient of entrepreneurial orientation is positive and significant (β = 0.1151, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 can be accepted. This paper then entered the four moderators, namely CEO duality, board independence, board ownership, and board size, and their interaction terms with entrepreneurial orientation in Models 2 to 5 to test Hypothesis 2 to Hypothesis 5 respectively. Model 2 examines the moderating effect of CEO duality, and the coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant (β = 0.0819, p < 0.05). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 can be accepted. Model 3 examines the moderating effect of board independence, and the coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant (β = 0.0784, p < 0.1). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 can be accepted. Model 4 examines the moderating effect of board ownership, and the coefficient of the interaction term is negative and significant (β = −0.1709, p < 0.1). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 can be accepted. Model 5 examines the moderating effect of the board size, and the coefficient of the interaction term is negative and significant (β = −0.0455, p < 0.1). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 can be accepted. Finally, the Model 6 includes all variables, and the results are consistent with previous models (Table 3).

To better explain the moderating effects of board characteristics, this paper utilized Aiken et al. (1991) approach to draw the interaction effects, shown as Figs. 2 to 5.

Robustness tests

This paper performs two robustness tests to verify the research results. Firstly, considering that radical innovation is time consuming, it usually takes a long time to transfer innovation input to innovation output. To account for the possibility that patent outcomes may not be fully observed after a one-year lag, following the research of Yang et al. (2019), this paper further lagged the dependent variable (radical innovation) for two years and then examined whether entrepreneurial orientation still has a significant impact on it. The results are reported in Table 4. It can be seen that the robustness results are consistent with previous results, which indicated that the research results were robust.

Secondly, since the dataset covers a relatively long time period, there will be some events that may affect the results of this paper. One of the most important events is the trade and economic friction between China and the United States, starting in 2018. The trade and economic friction between China and the United States has escalated quickly. Then, the US government tightens the control of the exports of various technologies, which may affect the innovation of Chinese firms. Therefore, referring to the research of Lazzarini and Musacchio (2018), this paper removed the samples of 2018 and 2019, and performed the regression analysis again. The results are reported in Table 5. It can be seen that the robustness results are consistent with previous results, which indicated that the research results were robust.

Discussion

The results of the empirical analysis show that entrepreneurial orientation has a significant positive relationship with radical innovation. This finding is in line with the overall theoretical argument that entrepreneurial orientation is inherently an exploratory orientation, with a focus on pursuing innovation (Covin and Wales, 2019). This paper further advances that idea, and is meant to develop the arguments of how entrepreneurial orientation positively related to radical innovation. Corresponding to the three dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation, the reasons why high entrepreneurial orientation firms may be advantaged in radical innovation can be summarized as three aspects, including motivation reason, opportunity reason and ability reason (Jiang et al. 2018). In the aspect of the motivation reason, high entrepreneurial orientation firms can always engage in innovation activities, and want to bring forward innovations to prevail over competitors (Wu et al. 2008). Therefore, compared to the firms with lower entrepreneurial orientation, high entrepreneurial orientation firms may have stronger motivations to engage in radical innovation. In the aspect of the opportunity reason, high entrepreneurial orientation firms always act more quickly rather than waiting (Fernández-Mesa and Alegre, 2015). This could lead them to be among the first to gain innovation opportunities. Therefore, firms with higher entrepreneurial orientation may have more opportunities to achieve radical innovation. In the aspect of the ability reason, radical innovation itself is a risky activity as it involves substantial efforts. While entrepreneurial orientation firms can always resolve the unknown difficulties in radical innovation. In this sense, entrepreneurial orientation firms are likely to be activated because these firms are more willing to bear uncertainty (Genc et al. 2019). All together, entrepreneurial orientation firms have a good potential to succeed in radical innovation.

Based on the direct effect, this paper also explored under which context the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation can be strengthened or weakened. This paper found that the board characteristics could exert important impacts on that relationship, which confirms the idea that entrepreneurial orientation should be properly managed in order to realize its full potential (Engelen et al. 2015). The board is the cornerstone to a firm, and the characteristics of the board could affect how a board actually behaves (Klarner et al. 2020). Therefore, this paper examines whether and how board characteristics may affect the positive effect of entrepreneurial orientation. This paper found that different board characteristics have different moderating effects. In detail, CEO duality and board independence positively moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, while board ownership and board size negatively moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. CEO duality and board independence are both the characteristics of board composition. CEO duality provides a clear-cut leadership that removes any ambiguity, and more independent director will provide firms with more potential resources. Both of them may enhance the motivation reason, opportunity reason and ability reason of the linkage between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, and thus contribute firms to employ their entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation. However, although board ownership and board size can be assumed to be beneficial for firms, considering the entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation context, board ownership and board size may be ineffective because they may bring addition agency costs to firms. Therefore, the moderating effects of board ownership and board size are different from CEO duality and board independence, which presents the asymmetric roles.

The asymmetric roles of board characteristics are also consistent with the arguments of the effects of board characteristics (Kurzhals et al. 2020), and further provides a configurational perspective in understanding how to construct a board to achieve radical innovation through entrepreneurial orientation. According to the results, firms should control the board size and adopt the CEO duality structure. At the same time, the CEO should also appoint independent directors as much as possible. The limited board size and CEO duality structure can reduce the conflicts within the board. While the independent directors appointed by the CEOs could help them acquire more resources to implement their decisions. This kind of board is a CEO-centric, which is important for entrepreneurial orientation firms to develop radical innovation. This is also in line with previous research, which has been proposed that in firms that are successful at radical innovation, senior leadership involvement with decision-making style will be high (Robeson and O’Connor, 2007). Therefore, this paper proposes that firms should consider different board characteristics simultaneously, which provides critical insights about how to construct a board for firms to employ entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation.

Based on the research results, this paper contributes to the relevant literature in the following three ways. Firstly, this paper this paper contributes to the literature on entrepreneurial orientation by demonstrating its direct and positive antecedent effect on radical innovation. Although the study of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation abounds (Zhang et al. 2016; Genc et al. 2019; Kohtamäki et al. 2020), the specific focus on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is very limited (Ato Sarsah et al. 2020; Salavou and Lioukas, 2003). For instance, Ato Sarsah et al. (2020) found that entrepreneurial orientation has a positive effect on radical innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. Based on previous research, this paper also focuses on the specific relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, and further offers three underlying mechanisms to explain how entrepreneurial orientation affects radical innovation. These three underlying mechanisms provide fresh insights into why entrepreneurial orientation plays its role in firm innovation. Therefore, this paper advances the literature on entrepreneurial orientation by extending its role and further strengthening the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation.

Secondly, this paper contributes to the corporate governance literature identifying the contingent effect of board characteristics on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. Although the internal factors that may influence the effect of entrepreneurial orientation have been investigated, most of them focus on top management leadership (Engelen et al. 2015; Palmer et al. 2019). For instance, Palmer et al. (2019) revealed that the combination of entrepreneurial orientation, dominance, and self-efficacy contribute to firm performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. The previous research suggests that corporate governance, which has important impacts on top management leadership, can be a boundary condition in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. Therefore, this paper empirically explores the contingency effects of board characteristics to explain when and how the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is unlikely to be consistent across firms. The results showed that board characteristics can moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. The results of this paper thus contribute to the corporate governance literature by establishing corporate governance as an important boundary condition of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm innovation, which could explain when and how a firm will benefit more from entrepreneurial orientation. Moreover, this paper also opens a new research area to stimulate the investigation of other contingency contexts of the effect of entrepreneurial orientation, which can provide new elaborations and further help to build new theory on the effect of entrepreneurial orientation.

Thirdly, this paper also makes a significant contribution to corporate governance research by revealing the asymmetric roles of board characteristics, which deepens the understanding of the role of a firm’s board in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. Previous research always examines one or two board characteristics (Almor et al. 2022; Griffin et al. 2021), often neglecting that different board characteristics may play asymmetric roles. For instance, Griffin et al. (2021) focused on board gender diversity, and found that more gender diverse boards are associated with more novel patents. Building on the previous research, this paper found that CEO duality and board independence play positive moderating effects, while board ownership and board size play negative moderating effects. These results suggest that the successful implementation of entrepreneurial orientation cannot be fully achieved by a single factor, but requires the configuration of different board characteristics. Therefore, this paper extends the corporate governance research by demonstrating that the effects of board characteristics are more complex than previously assumed. The asymmetric roles of board characteristics also further offer a more comprehensive account of what kind of board that entrepreneurial orientation firms can use to achieve radical innovation, which calls for investigating how to integrate different corporate governance mechanisms that can ensure the effect of entrepreneurial orientation.

Conclusion

Based on the data of manufacturing firms listed in Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2013 to 2019, this paper found that entrepreneurial orientation has a significant positive relationship with radical innovation. Furthermore, different board characteristics play asymmetric moderating roles in that relationship. To be specific, CEO duality and board independence positively moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation, while board ownership and board size negatively moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Practical implications

This paper also provides some important practical implications. Firstly, this paper finds that entrepreneurial orientation has a significant positive relationship with radical innovation, which suggests that firms should attach importance to the cultivation of entrepreneurial orientation. The possible practices include lay strong emphasis on R&D, adopts a bold posture to maximize the potential of opportunities, and to be first to introduce new products (Genc et al. 2019). Secondly, the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is positively moderated by CEO duality and board independence. Therefore, in order to reap more benefits from entrepreneurial orientation, firms should adopt the CEO duality structure and appropriately increase the proportion of independent directors in the board. Thirdly, the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation is negatively moderated by board ownership and board size. Therefore, in order to avoid such negative effects, firms should control board share incentives and board size.

Limitations and future research

This paper also suffers some limitations that need to be addressed by future research. Firstly, this paper only uses patent applications to measure radical innovation. However, some firms may not choose the form of patents to protect their radical innovations. Therefore, the measurement of radical innovation in this paper may be biased. In order to address this issue, further research should create a more effective measurement for radical innovation.

Secondly, although this paper analyzed how entrepreneurial orientation affects radical innovation, the mediation mechanisms of that connection are not explored. In order to get more understandings about the effect of entrepreneurial orientation, future research is needed to examine the mediation mechanisms of how entrepreneurial orientation affects radical innovation. For example, Ato Sarsah et al. (2020) has found that absorptive capacity mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation performance among manufacturing small and medium-sized enterprises. Future research might draw on other relevant theories to examine other potential mediation mechanisms linking entrepreneurial orientation to radical innovation.

Thirdly, in addition to board characteristics, other corporate governance mechanisms can be considered as important internal contingency contexts. For example, Su and Sauerwald (2018) found that the corporate governance of CEO compensation is also an important internal contingency context. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate how CEO compensation affects the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation.

Lastly, the sample of this paper is limited to Chinese manufacturing listed firms. With aims to generalize the research results, it is suggested that the sample in other countries should be analyzed.

Overall, this paper has found that there exists a significant positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. This paper also systematically examined how board characteristics may affect the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation. The findings offer important hints about how to employ entrepreneurial orientation to achieve radical innovation, which can be a new step for the related research.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adams RB, Hermalin BE, Weisbach MS (2010) The role of boards of directors in corporate governance: A conceptual framework and survey. J Econ Lit 48(1):58–107

Ahmed K, Hossain M, Adams MB (2006) The effects of board composition and board size on the informativeness of annual accounting earnings. Corp Gov 14(5):418–431

Akbar S, Kharabsheh B, Poletti-Hughes J, Shah SZA (2017) Board structure and corporate risk taking in the UK financial sector. Int Rev Financ Anal 50(3):101–110

Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage

Almor T, Bazel-Shoham O, Lee SM (2022) The dual effect of board gender diversity on R&D investments. Long Range Plan 55(2):101884

Ato Sarsah S, Tian H, Dogbe CSK, Pomegbe WWK (2020) Effect of entrepreneurial orientation on radical innovation performance among manufacturing SMEs: The mediating role of absorptive capacity. J Strategy Manag 13(4):551–570

Arzubiaga U, Kotlar J, De Massis A, Maseda A, Iturralde T (2018) Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation in family SMEs: Unveiling the (actual) impact of the board of directors. J Bus Ventur 33(4):455–469

Anderson BS, Kreiser PM, Kuratko DF, Hornsby JS, Eshima Y (2015) Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg Manage J 36(10):1579–1596

Ben Rejeb W, Berraies S, Talbi D (2020) The contribution of board of directors’ roles to ambidextrous innovation: Do board’s gender diversity and independence matter? Eur J Innov Manag 23(1):40–66

Boivie S, Bednar MK, Aguilera RV, Andrus JL (2016) Are boards designed to fail? The implausibility of effective board monitoring. Acad Manag Ann 10(1):319–407

Boyd BK (1995) CEO duality and firm performance: A contingency model. Strateg Manage J 16(4):301–312

Brasil VC, Salerno MS, Eggers JP, de Vasconcelos Gomes LA (2021) Boosting radical innovation using ambidextrous portfolio management: To manage radical innovation effectively, companies can build ambidextrous portfolio management systems and adopt a multilevel organizational approach. Res-Technol Manage 64(5):39–49

Carr JC, Haggard KS, Hmieleski KM, Zahra SA (2010) A study of the moderating effects of firm age at internationalization on firm survival and short-term growth. Strateg Entrep J 4(2):183–192

Chang YC, Chang HT, Chi HR, Chen MH, Deng LL (2012) How do established firms improve radical innovation performance? The organizational capabilities view. Technovation 32(7-8):441–451

Chang CH, Wu Q (2021) Board networks and corporate innovation. Manage Sci 67(6):3618–3654

Chen HL, Hsu WT, Chang CY (2016) Independent directors’ human and social capital, firm internationalization and performance implications: An integrated agency-resource dependence view. Int Bus Rev 25(4):859–871

Chen HL (2011) Does board independence influence the top management team? Evidence from strategic decisions toward internationalization. Corp Gov 19(4):334–350

Cheng S (2008) Board size and the variability of corporate performance. J Financ Econ 87(1):157–176

Chi J, Liao J, Yang J (2019) Institutional stock ownership and firm innovation: Evidence from China. J Multinatl Financ Manag 50(6):44–57

Chirico F, Ireland RD, Pittino D, Sanchez-Famoso V (2022) Radical innovation in (multi) family owned firms. J Bus Ventur 37(3):106194

Choi SB, Lee SH, Williams C (2011) Ownership and firm innovation in a transition economy: Evidence from China. Res Policy 40(3):441–452

Choi SB, Park BI, Hong P (2012) Does ownership structure matter for firm technological innovation performance? The case of Korean firms. Corp Gov 20(3):267–288

Cortes AF, Herrmann P (2021) Strategic leadership of innovation: A framework for future research. Int J Manag Rev 23(2):224–243

Covin JG, Lumpkin GT (2011) Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrep Theory Pract 35(5):855–872

Covin JG, Wales WJ (2019) Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: Some suggested guidelines. Entrep Theory Pract 43(1):3–18

Cumming D, Leung TY (2021) Board diversity and corporate innovation: Regional demographics and industry context. Corp Gov 29(3):277–296

Dana LP, Salamzadeh A, Mortazavi S, Hadizadeh M (2022) Investigating the impact of international markets and new digital technologies on business innovation in emerging markets. Sustainability 14(2):983

Desai VM (2016) The behavioral theory of the (governed) firm: Corporate board influences on organizations’ responses to performance shortfalls. Acad Manage J 59(3):860–879

Domínguez-Escrig E, Mallén-Broch FF, Lapiedra-Alcamí R, Chiva-Gómez R (2019) The influence of leaders’ stewardship behavior on innovation success: the mediating effect of radical innovation. J Bus Ethics 159(3):849–862

Engelen A, Gupta V, Strenger L, Brettel M (2015) Entrepreneurial orientation, firm performance, and the moderating role of transformational leadership behaviors. J Manag 41(4):1069–1097

Eshima Y, Anderson BS (2017) Firm growth, adaptive capability, and entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg Manage J 38(3):770–779

Farrer J, Ramsay I (1998) Director share ownership and corporate performance-evidence from Australia. Corp Gov 6(4):233–248

Fernández-Mesa A, Alegre J (2015) Entrepreneurial orientation and export intensity: Examining the interplay of organizational learning and innovation. Int Bus Rev 24(1):148–156

Ferreras-Méndez JL, Llopis O, Alegre J (2022) Speeding up new product development through entrepreneurial orientation in SMEs: The moderating role of ambidexterity. Ind Mark Manage 102(4):240–251

Forés B, Camisón C (2016) Does incremental and radical innovation performance depend on different types of knowledge accumulation capabilities and organizational size? J Bus Res 69(2):831–848

Freixanet J, Rialp J (2022) Disentangling the relationship between internationalization, incremental and radical innovation, and firm performance. Glob Strateg J 12(1):57–81

Genc E, Dayan M, Genc OF (2019) The impact of SME internationalization on innovation: The mediating role of market and entrepreneurial orientation. Ind Mark Manage 82(10):253–264

Gillan SL (2006) Recent developments in corporate governance: An overview. J Corp Financ 12(3):381–402

Griffin D, Li K, Xu T (2021) Board gender diversity and corporate innovation: International evidence. J Financ Quant Anal 56(1):123–154

He F, Ma Y, Zhang X (2020) How does economic policy uncertainty affect corporate Innovation?-Evidence from China listed companies. Int Rev Econ Financ 67(5):225–239

Hernández-Lara AB, Camelo-Ordaz C, Valle-Cabrera R (2014) Does board member stock ownership influence the effect of board composition on innovation? Eur J Int Manag 8(4):355–372

Hillman AJ, Dalziel T (2003) Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Acad Manage Rev 28(3):383–396

Honoré F, Munari F, de La Potterie BP (2015) Corporate governance practices and companies’ R&D intensity: Evidence from European countries. Res. Policy 44(2):533–543

Hughes M, Chang YY, Hodgkinson I, Hughes P, Chang CY (2021) The multi-level effects of corporate entrepreneurial orientation on business unit radical innovation and financial performance. Long Range. Plan 54(1):101989–102016

Hughes M, Morgan RE (2007) Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Ind Mark Manage 36(5):651–661

Hult GTM, Hurley RF, Knight GA (2004) Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Ind Mark Manage 33(5):429–438

Jiang W, Wang AX, Zhou KZ, Zhang C (2020) Stakeholder relationship capability and firm innovation: A contingent analysis. J Bus Ethics 167(1):111–125

Jiang X, Liu H, Fey C, Jiang F (2018) Entrepreneurial orientation, network resource acquisition, and firm performance: A network approach. J Bus Res 87(6):46–57

Kim B, Burns ML, Prescott JE (2009) The strategic role of the board: The impact of board structure on top management team strategic action capability. Corp Gov 17(6):728–743

Klarner P, Probst G, Useem M (2020) Opening the black box: Unpacking board involvement in innovation. Strateg Organ 18(4):487–519

Kocak A, Carsrud A, Oflazoglu S (2017) Market, entrepreneurial, and technology orientations: Impact on innovation and firm performance. Manag Decis 55(2):248–270

Kohtamäki M, Heimonen J, Sjödin D, Heikkilä V (2020) Strategic agility in innovation: Unpacking the interaction between entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity by using practice theory. J Bus Res 118(9):12–25

Krause R, Semadeni M, Cannella Jr AA (2014) CEO duality: A review and research agenda. J Manag 40(1):256–286

Kurzhals C, Graf-Vlachy L, König A (2020) Strategic leadership and technological innovation: A comprehensive review and research agenda. Corp Gov 28(6):437–464

Kyrgidou LP, Spyropoulou S (2013) Drivers and performance outcomes of innovativeness: An empirical study. Brit J Manage 24(3):281–298

Lazzarini SG, Musacchio A (2018) State ownership reinvented? Explaining performance differences between state-owned and private firms. Corp Gov 26(4):255–272

Li Y, Gao Y, Gao S (2023) Organizational slack, entrepreneurial orientation, and corporate political activity: From the behavioral theory of the firm. Hum Soc. Sci Commun 10(1):1–12

Li Y, Liu Y, Xie F (2019) Technology directors and firm innovation. J Multinatl Financ Manag 50(6):76–88

Lomberg C, Urbig D, Stöckmann C, Marino LD, Dickson PH (2017) Entrepreneurial orientation: The dimensions’ shared effects in explaining firm performance. Entrep Theory Pract 41(6):973–998

Lu J, Wang W (2018) Managerial conservatism, board independence and corporate innovation. J Corp Financ 48(2):1–16

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (2001) Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J Bus Ventur 16(5):429–451

Miller D (1983) The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manage Sci 29(7):770–791

Munjal S, Requejo I, Kundu SK (2019) Offshore outsourcing and firm performance: Moderating effects of size, growth and slack resources. J Bus Res 103(10):484–494

Nakano M, Nguyen P (2012) Board size and corporate risk taking: Further evidence from Japan. Corp Gov 20(4):369–387

O’Connor GC, Rice MP (2013) A comprehensive model of uncertainty associated with radical innovation. J Prod Innov Manage 30(9):2–18

Oh WY, Chang YK, Martynov A (2011) The effect of ownership structure on corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from Korea. J Bus Ethics 104(2):283–297

Palmer C, Niemand T, Stöckmann C, Kraus S, Kailer N (2019) The interplay of entrepreneurial orientation and psychological traits in explaining firm performance. J Bus Res 94(1):183–194

Peng MW, Li Y, Xie E, Su Z (2010) CEO duality, organizational slack, and firm performance in China. Asia Pac J Manag 27(4):611–624

Peng YS, Fang CP (2010) Acquisition experience, board characteristics, and acquisition behavior. J Bus Res 63(5):502–509

Pérez-Luño A, Wiklund J, Cabrera RV (2011) The dual nature of innovative activity: How entrepreneurial orientation influences innovation generation and adoption. J Bus Ventur 26(5):555–571

Petruzzelli AM, Ardito L, Savino T (2018) Maturity of knowledge inputs and innovation value: The moderating effect of firm age and size. J Bus Res 86(5):190–201

Putniņš TJ, Sauka A (2020) Why does entrepreneurial orientation affect company performance? Strateg Entrep J 14(4):711–735

Ramdani D, Witteloostuijn A (2010) The impact of board independence and CEO duality on firm performance: A quantile regression analysis for Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea and Thailand. Brit J Manage 21(3):607–627

Rampa R, Agogué M (2021) Developing radical innovation capabilities: Exploring the effects of training employees for creativity and innovation. Creat Innov Manag 30(1):211–227

Rank ON, Strenge M (2018) Entrepreneurial orientation as a driver of brokerage in external networks: Exploring the effects of risk taking, proactivity, and innovativeness. Strateg Entrep J 12(4):482–503

Rauch A, Wiklund J, Lumpkin GT, Frese M (2009) Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep Theory Pract 33(3):761–787

Robeson D, O’Connor G (2007) The governance of innovation centers in large established companies. J Eng Technol Manage 24(1-2):121–147

Rong Z, Wu X, Boeing P (2017) The effect of institutional ownership on firm innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Res Policy 46(9):1533–1551

Ruigrok W, Peck SI, Keller H (2006) Board characteristics and involvement in strategic decision making: Evidence from Swiss companies. J Manage Stud 43(5):1201–1226

Saeedikiya M, Aeeni Z (2020) Innovation and growth ambition of female entrepreneurs: A comparison between the MENA region and the rest of the world. MENA J Cross Cult. Manag 1(1):7–19

Saeedikiya M, Li J, Ashourizadeh S, Temiz S (2021) Innovation affecting growth aspirations of early stage entrepreneurs: Culture and economic freedom matter. J Entrep Emerg Econ 14(1):45–64

Sainio LM, Ritala P, Hurmelinna-Laukkanen P (2012) Constituents of radical innovation-exploring the role of strategic orientations and market uncertainty. Technovation 32(11):591–599

Salamzadeh A, Hadizadeh M, Rastgoo N, Rahman MdM, Radfard S (2022) Sustainability-oriented innovation foresight in international new technology based firms. Sustainability 14(20):13501

Salavou H, Lioukas S (2003) Radical product innovations in SMEs: The dominance of entrepreneurial orientation. Creat Innov Manag 12(2):94–108

Sandberg B, Aarikka-Stenroos L (2014) What makes it so difficult? A systematic review on barriers to radical innovation. Ind Mark Manage 43(8):1293–1305

Sapra H, Subramanian A, Subramanian KV (2014) Corporate governance and innovation: Theory and evidence. J Financ Quant Anal 49(4):957–1003

Su W, Sauerwald S (2018) Does corporate philanthropy increase firm value? The moderating role of corporate governance. Bus Soc 57(4):599–635

Szymanski DM, Kroff MW, Troy LC (2007) Innovativeness and new product success: Insights from the cumulative evidence. J Acad Mark Sci 35(1):35–52

Tajpour M, Hosseini E, Salamzadeh A (2020) The effect of innovation components on organisational performance: Case of the governorate of Golestan province. Int J Public Sect Perform Manage 6(6):817–830

Tang J (2017) CEO duality and firm performance: The moderating roles of other executives and blockholding outside directors. Eur Manag J 35(3):362–372

Wales WJ, Covin JG, Monsen E (2020) Entrepreneurial orientation: The necessity of a multilevel conceptualization. Strateg Entrep J 14(4):639–660

Wang G, DeGhetto K, Ellen BP, Lamont BT (2019) Board antecedents of CEO duality and the moderating role of country‐level managerial discretion: A meta-analytic investigation. J Manage Stud 56(1):172–202

Wang H, Zhao S, He J (2016) Increase in takeover protection and firm knowledge accumulation strategy. Strateg Manage J 37(12):2393–2412

Williams C, Lee SH (2009) Resource allocations, knowledge network characteristics and entrepreneurial orientation of multinational corporations. Res. Policy 38(8):1376–1387

Wincent J, Anokhin S, Boter H (2009) Network board continuity and effectiveness of open innovation in Swedish strategic small-firm networks. R&D Manage 39(1):55–67

Wiseman RM, Gomez-Mejia LR (1998) A behavioral agency model of managerial risk taking. Acad Manage Rev 23(1):133–153

Wu WY, Chang ML, Chen CW (2008) Promoting innovation through the accumulation of intellectual capital, social capital, and entrepreneurial orientation. R&D Manage 38(3):265–277

Wu S, Levitas E, Priem RL (2005) CEO tenure and company invention under differing levels of technological dynamism. Acad Manage J 48(5):859–873

Wu J, Wu Z (2014) Integrated risk management and product innovation in China: The moderating role of board of directors. Technovation 34(8):466–476

Yang D, Wang AX, Zhou KZ, Jiang W (2019) Environmental strategy, institutional force, and innovation capability: A managerial cognition perspective. J Bus Ethics 159(4):1147–1161

Yang L, Wang D (2014) The impacts of top management team characteristics on entrepreneurial strategic orientation: The moderating effects of industrial environment and corporate ownership. Manag Decis 52(2):378–409

Yazdanpanah Y, Toghraee MT, Salamzadeh A, Scott JM, Palalić M (2023) The influence of entrepreneurial culture and organizational learning on entrepreneurial orientation: The case of new technology-based firms in Iran. Int J Entrep Behav Res 29(5):1181–1203

Yuan R, Wen W (2018) Managerial foreign experience and corporate innovation. J Corp Financ 48(2):752–770

Zhang JA, Edgar F, Geare A, O’Kane C (2016) The interactive effects of entrepreneurial orientation and capability-based HRM on firm performance: The mediating role of innovation ambidexterity. Ind Mark Manage 59(11):131–143

Zhou KZ, Gao GY, Zhao H (2017) State ownership and firm innovation in China: An integrated view of institutional and efficiency logics. Adm Sci Q 62(2):375–404

Zhou KZ, Li CB (2012) How knowledge affects radical innovation: Knowledge base, market knowledge acquisition, and internal knowledge sharing. Strateg Manage J 33(9):1090–1102

Zona F, Zattoni A, Minichilli A (2013) A contingency model of boards of directors and firm innovation: The moderating role of firm size. Brit J Manage 24(3):299–315

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72072047), Social Science Planning Project of Shandong Province (Grant No. 22CSDJ03) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. HIT.HSS.ESD202310).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YXL and WWW conceived, wrote and approved the manuscript. YCW acquired and analyzed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Wu, Y. & Wu, W. Which kind of board benefits more from the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and radical innovation? The asymmetric roles of board characteristics in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 388 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01906-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01906-5

- Springer Nature Limited