Abstract

This study compares the protective effectiveness of Social Safety Nets (SSNs) provided by government and NGOs in rural Pakistan, using quasi-experimental methodology on PRPHS (2011–12) data. The treatment group was the households receiving SSNs assistance. The counterfactual (control group) was determined using propensity score matching. Outcome indicators were shock-coping strategies from which households are theoretically protected from by SSNs: reducing food consumption, switching to cheaper food, and distress asset sales. The impact of both types of SSNs was calculated by average treatment effect on the treatment group. The results showed insignificantly lesser treatment units used shock-coping strategies than the matched control unit, implying that receiving either type of SSN did not protect the household from resorting to coping strategies. However, households with public SSNs tended not to resort to switching to cheaper food as a coping strategy. This suggests that public SSNs have more protective effectiveness than private SSNs. JEL classification H31, H53, H55, H76.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an attempt to address the issue of burgeoning susceptibility of shocks among the vulnerables in developing countries, social safety nets (SSNs) have emerged as a potential solution and are currently the focus of an extensive policy debate. SSNs are defined by FAO as cash or in-kind transfer programmes that seek to reduce poverty by redistributing wealth and/or protect households against income shocks. SSNs seek to maintain a minimum level of well-being, a minimum level of nutrition, and help households manage risk. Shocks are the negative economic events that can be related to many aspects for example physical health, natural disasters, or economic crises. Depending upon the number of affected individuals, shocks can be classified into two types: idiosyncratic; where a household or few community members get affected, and covariate; which affect a large number of households at the same time (Lustig 2001).

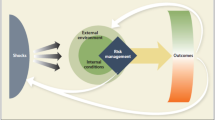

One of the main intended goals of SSNs is to protect the poor and vulnerable segments of the population by guarding them against resorting to such shock coping strategies that may compromise their existing level of welfare (Nayab and Farooq 2012). Theoretically, SSNs act as an intervention, received by the targeted household (which is classified as “vulnerable” by the provider) in the form of cash, training, food, or other assets. New pathways are opened to the beneficiaries of SSNs through various mechanisms, such as giving the household more purchasing power that were not available to these households beforehand. For example, the relief in short-term stresses of consumption frees up resources for the households to make them more resilient. The impact of SSNs is manifested in various productive outcomes, such as accumulation of human capital and assets, food security and shock coping strategies, and the final intended goal through these productive outcomes is achieved in terms of poverty reduction and risk coping. It is theorised by SSN providers that the programs protect households from resorting to detrimental shock coping strategies, providing them a cushion to cope with shocks.

SSNs have various manifestations internationally; from the well-established formal social security system in the United States, to the informal Hawala system in Muslim countries (Morduch and Sharma 2002). SSNs, such as cash transfers, are often implemented in developing countries as a disaster/emergency response or an intervention that promotes inclusion of the vulnerable into the economy. Impact evaluations of SSNs in developing countries suggest moderate impacts [for example, see Akter et al. 2014; Rahman and Choudhury 2012]. Well designed SSNs which are implemented properly and delivered regularly show greater productive outcomes [for example, see Gilligan et al. (2009)].

In Pakistan, several SSNs are operational. They have especially become relevant in policy discourse after the 2008 food price hike and the launch of the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP). However, there is a lack of evidence-based assessments regarding SSNs in Pakistan. The Pakistan Economic Survey and other impact assessments mostly present superficial indicators, that do not shed any light on how SSNs are performing in terms of achieving their ambitious goals. In a report by the World Bank (2013), regarding the impact of the 2008 food price hike, descriptive analysis revealed that the main shock coping strategies in both rural and urban areas of Pakistan were reducing food consumption and switching to cheaper food.

Out of the SSNs implemented in Pakistan, Zakat and Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) have been investigated extensively (Toor and Nasar 2004; Nayab and Farooq 2012; Cheema et al. 2014), while other SSNs have usually been analyzed via superficial indicators. Besides, the websites of the various NGOs publish reports on situational analyses of their targeted areas as well as impact assessments on various indicators (most notably of their community and infrastructure projects, though not on resilience). Before the introduction of BISP, there were two cash transfer programs in the SSN framework of Pakistan; Zakat and the Food Support Program undertaken by Bait-ul-Maal, both of which were inefficient in their targeting as only 46% and 43% of the former and latter was transferred to the most vulnerable 40% of the population (World Bank 2013).

The motivation for this study comes through a lack of evidence-based assessments regarding the relative effectiveness of public versus private SSNs in Pakistan. An analysis of the effectiveness of SSNs has not been carried out for rural Pakistan. It is pertinent to investigate the shock mitigating role of SSNs in rural Pakistan, as data from existing cross-sectional surveys in Pakistan, such as Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement, indicate that poverty is concentrated in rural areas.

The dataset used in this study is the first round of the PRPHS (Pakistan Rural Panel Household Survey) collected by the International Food Policy and Research Institute in 2011–12. It is the most appropriate data set for this investigation as a nation-wide flood had hit the country 12 months prior to the survey. The survey is based on the most immediate period after the disaster and thus become an effective data set for analysis of SSNs in mitigating the impact of shock in rural Pakistan. By using a quasi-experimental design, this study provides a comparative evidence-based analysis on the relative protective efficiency of public (by the Government) and private (provided by NGOs) SSNs for the rural households of Pakistan. This study would determine whether SSNs pose any impact on shock coping strategies of beneficiary households in the rural Pakistan, along with assessment of which type of SSNs (public or private) is more effective. This study enriches the already existing literature in the domain of social safety nets (incorporating a comparable analysis of Govt versus private SSNs) in a developing country like Pakistan. The contribution of this study becomes more pronounced and relevant in the wake of recent disastrous floods, since the study is based on data set collected in the most immediate period after the floods of 2009–10. The findings of this research can be employed as a guideline by both public and private sector SSN providers for effective implementation of SSNs to mitigate the impact of shocks faced by current flood affected population.

Literature review

A crucial aspect of an individual’s living standard is their resilience—the capability to absorb shocks and still retain fundamental functioning. Therefore, a resilient individual is one who does not have to resort to a detrimental coping strategy due to a shock. Following this argument, in an inequitable society, the vulnerable segment of the population is warranted some mechanism of redistribution of wealth that would ensure their resilience. A safety net is supposed to act as an insurance against the risks of adverse events. If it is to be believed that having a cushion against shocks is a valuable aspect of an adequate living standard and that private markets may be unable to provide it (especially in the case of developing countries), then a case can be built for social safety nets to be a part of the policy framework (Cowen et al. 2012).

In this context, the concept of the Social Protection Floor (SPF) is relevant; a concept put forth by United Nations Chief Executives Board for Coordination, for a repertoire of basic human rights that must be ensured for every citizen. SSNs are a major part of SPF and ILO has been a major advocate of these SSNs. (ILO 2015; Haan 2014). SSNs are rigorously assessed in various aspects throughout the world for their effectiveness. However, social protection system/SSNs in high income developed countries were adopted quite early as compared to developing countries. Nevertheless, the developing countries still prioritize them as an important agenda of their public policies on account of growing inequalities and vulnerabilities prevalent in these economies. (Haan 2014). Another important aspect about these SSNs is that in developed countries they mostly comprise of pension schemes and social security, while social protection in less developed countries is mostly constituted by informal systems, such as the Hawala system in Muslim countries, or help from the community and relatives (Morduch and Sharma 2002).

Over the past decade, there has been an empirical shift with more emphasis being placed on evidence-based policy prescriptions. Thus, statistically powerful methods, particularly experimental designs, are increasingly being adopted to assess policy interventions such as SSNs (Blattman 2015). Besides, since 2007–08 world food price hike SSNs have been more widely implemented in different less developed countries to protect the vulnerable segment of the population. In a comprehensive comparative study of the productive outcomes of six different SSNs operative in Bangladesh, Akter et al. (2014) employed ‘Propensity Score Matching’ and calculated average treatment effects on the treated using data from Bangladesh HIES 2010. The findings suggested that standalone SSNs are largely ineffective in terms of protecting the households from detrimental shock coping strategies. However, households that were on multiple SSNs showed significantly better outcomes.

Another assessment on SSNs in Bangladesh by Rahman and Choudhury (2012) showed that the programs enhanced food security in terms of the reduction in volatility of hunger periods, with more availability of food. Assessment of crisis coping mechanisms before and after the programs showed significant reduction in distress sales of assets, but insignificant impact on dependency on high-interest credit. Furthermore, a study by Gilligan et al. (2009) used data from a household survey in 4 principal regions covered by the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) in Ethiopia and calculated the average treatment effect on the treatment group to ascertain the impact of the program. Households receiving the PSNP had a higher likelihood of being food secure than those that did not. Despite leakages and inefficient targeting, an impact assessment by Galasso and Ravallion (2003) of the income support program in Argentina to facilitate unemployed individuals as a response to the 2002 economic downturn showed that the program had unemployment reduction effects and moderately recouped the vulnerable. Devereux’s (2002) three case studies on SSNs pertaining to South Africa showed that the programs that are thought of only being helpful in relieving short term stresses can actually improve livelihoods if provided regularly and properly.

In an analysis of Public Assistance Program in Zimbabwe, Munro (2005) found that the program was ineffective in supporting those living in chronic poverty as it was not only weak in terms of coverage of its target group but was also unable to provide benefits to its clients. The study by Chininga (2005) based on qualitative simulation, conducted in Malawi, however, provides suggestive measures for targeting safety net intervention. The finding of study support principle of community targeting to maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of any targeted intervention.

A study conducted on the Child Support Grant in South Africa (which was unconditional) using continuous treatment method revealed that the SSN had a surprisingly significant impact on childhood nutrition that translated into better labor market outcomes for the children in recipient households (Aguero et al. 2007). An impact evaluation by Soares et al. (2010) of the conditional cash transfer (CCT) program, Tekopora, showed that the program apart from having positive effects on schooling, health and consumption outcomes had also the positive effects on other outcomes such as identity card possession and cultivation of a saving behavior. A meta-analysis of 35 different case studies of SSNs in developing countries by Baird et al. (2014) showed that both Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) and CCTs increased the likelihood of school enrollment with no significant difference between the two. In disaster-hit areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa affected households are diverse. Cash transfers as opposed to a package of other SSNs seem to be the quickest and the most effective emergency response (Adato and Bassett 2009). In a report by the World Bank (2013), PSLM data for the 2008–10 round was used for descriptive analysis and elasticity calculations to gauge the impact of the 2008 food price hike. The descriptive analysis revealed that the main shock coping strategies in both rural and urban areas of Pakistan were reducing food consumption and switching to cheaper food.

A study on Zakat by Toor and Nasar (2004) used a crude experimental technique to find a counterfactual of non-recipients of Zakat on basis of similar characteristics to gauge differences in the socioeconomic status of recipients and non-recipients. The findings suggested significant differences in meat expenditure, education expenditure, and house ownership for rural areas. Nayab and Farooq (2012) employed ‘Propensity Score Matching’ and calculated average treatment effect on the treatment group to evaluate the impact of BISP on four indicators of welfare: school enrollment, employment status of women, per capita health expenditure, and per capita food expenditure. The evidence suggested that BISP had a positive but insignificant effect on these indicators. In the first follow-up impact evaluation of BISP, Cheema et al. (2014) analyzed the program extensively in various aspects using a mixed methods approach that combined quantitative and qualitative methods. Using baseline and end-line survey data collected by Oxford Policy Management in 2011 and 2013 respectively, the researchers employed Regression Discontinuity Design and found that BISP had an insignificant impact on consumption expenditure although beneficiary households predominantly used the transfer on food and nutrition related expenses. Descriptive analysis of beneficiaries showed a major proportion of them still resorting to drastic coping strategies (such as reducing food consumption) as response to shocks. In a study on BISP pertaining to Tehsil Mankera District Bhakkar, Naqvi et al. (2014) employed Chow test to deduce whether the program caused a structural break in the socio-economic status of the beneficiaries under study. The results suggested that the program led to a structural break in the socioeconomic status of the recipients as indicated by increases in consumption expenditure and improvement in assets and livelihoods of the beneficiary households.

Although there is a diverse assortment of Pakistan’s social protection system, however, except for BISP the outreach of other programs is limited. Besides, the impact of these programs on targeted beneficiaries is also debatable in literature. (ILO 2019; Iqbal et al. 2020). Pakistan also lacks in terms of achieving majority of the targets for implementing social protection system under SDG 1.5. (ILO 2021).

The existing literature pertains to the role of SSNs in mitigating the impact of shocks, however, a separate evaluation of public Vs private SSNs has not been conducted yet. In the case of Pakistan most of the studies conducted only investigated the effectiveness of public SSNs, while relative effectiveness of Public versus Private transfers has not been studied for rural areas of Pakistan. Furthermore, the dataset used in this study (PRPHS), that contains explicit and comprehensive sections on social safety nets and coping indicators associated with shocks has not been utilized for such an analysis beforehand.

Methodology and data

Theoretical context

The theoretical context of this study is adapted from Alderman & Yemstov (2012). An SSN acts as an intervention and is received by the targeted household (classified as “vulnerable” by the provider) in the form of cash, training, food, or other assets. Through providing various mechanisms such as giving the household more purchasing power certain pathways have been made available to the household which did not exist earlier. For example, as the short-term stresses of consumption are relieved resources are released for the households to make them more resilient. The impact of the SSN is manifested in various productive outcomes such as accumulation of human capital and assets, food security, and risk coping strategies. Final intended goals are poverty reduction and risk coping. Relevant to this study is the risk coping theoretical impact of SSNs. It is theorized by SSN providers that the programs protect households from resorting to detrimental shock coping strategies providing them a cushion to cope with shocks.

Methodology

Susceptibility to shocks is a dimension of poverty and SSNs and coping strategies are its indicators (Nazli and Haider 2012). This study analyses the impact of SSNs on shock coping strategies, whereby the outcome indicators considered were three detrimental coping strategies that receiving an SSN should ideally protect a household from resorting to: reduction in food consumption, switching to cheaper food, and distress sales of productive assets. This warranted the use of an experimental method that could facilitate in the investigation of whether a relationship exists between a household receiving an SSN and being effectively protected from resorting to the drastic coping strategies. Therefore, the analysis is essentially an impact evaluation, with impact being the difference between the observed outcome of the household (after receiving the SSN) and the alternative outcome, had the household not received the SSN. The latter is designated as counterfactual.

As the counterfactual does not exist, a proxy for it must be used. If the households receiving SSN are considered to be the treatment group then the counterfactual would be a control group; a group of households that is observationally similar, on average, to the treatment group, with the only difference of the control group not having received SSN. The difference in outcomes of interest between these groups can then be compared and checked for significance. Hence, if any effect is detected, it can be confidently attributed to SSN.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the available micro data, literature posits that for deriving an appropriate counterfactual the most suitable method is ‘Propensity Score Matching’ (PSM), first proposed by Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983). PSM is a quasi-experimental design that attempts to mimic the properties of a true experiment when only observational data is available. While initially used for drug trials, PSM is increasingly being used for assessing economic policy interventions (Becker and Ichino 2002). PSM can be used in cases when baseline data before the intervention is not available, such as in the studies by Nayab and Farooq (2012) and Akter et al. (2014). The PSM requires representative data of beneficiaries of the program being assessed and likewise of non-beneficiaries (preferably from the same survey or similar surveys). The treatment group is one that received the program while the potential control group is one that did not receive the program. These two samples are pooled.

Factors that can potentially determine program participation, institutional and administrative aspects as well as the eligibility criteria of the programs themselves are chosen as covariates. These covariates form the basis on which the counterfactual is selected. An assumption is held that the covariates (acting as pre-treatment characteristics) are not affected by the treatment and remain the same post treatment. The chosen covariates must satisfy the two conditions of balancing and un-confoundedness (Becker and Ichino 2002).

Commonly in PSM, a binary logistic regression is run on the pooled sample where the dependent variable is whether the unit received the program or not (Yes=1 and No=0) and independent variables are the covariates selected. The probability of receiving treatment as predicted by the model for each unit is designated as its propensity score. Through using one of various matching methods, each treatment unit is matched to a control unit with a similar propensity score thus providing an appropriate counterfactual. As economic policy interventions are often not rolled out randomly, PSM provides a remedy to the selection bias problem. After matching the difference between mean of the two group’s outcomes is derived. This is known as Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT). If it is statistically significant the evidence will suggest that the program has indeed an impact on the outcome of interest (Ravallion 2003).

To investigate the hypothesised relationship, PSM and ATT was employed as other methods of impact evaluation such as panel regression double difference (DD) and regression discontinuity design (RDD) require pre and post-program information on characteristics and outcomes which are not available for the current study. This method is also favored over a direct logistic regression as the latter assumes from the outset that the recipients and non-recipients are widely different thus rendering mean outcomes of the non-recipient group as an inappropriate benchmark for assessment.

Often, OLS regression is used where the outcome is the dependent variable and the treatment status is a dummy entering the model as an independent variable along with the chosen covariates. However, this requires the researcher to form restrictive assumptions about the parametric functional forms of the variables in the model. The use of logistic regression in PSM on the other hand, is free of this issue (Ravallion 2003).

Data

The dataset used in this study is the first round of the PRPHS (Pakistan Rural Panel Household Survey) collected by the International Food Policy and Research Institute in 2011–12 that contains data on 2124 rural households in Pakistan from the provinces of Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber PakhtunkhwaFootnote 1 (Nazli and Haider 2012). Two of the survey instruments were household level questionnaires administered on a representative male and a representative female from each respondent household. The questionnaires contained sections on shocks experienced by the household with associated coping strategies and social safety nets (if any) utilised by the household.

The SSNs covered in the survey have been split into two distinct categories:

-

a.

Public (given by the Government of Pakistan): These include Benazir Income Support Programme which is Pakistan’s main unconditional cash transfer programme; Watan Card scheme, which was a cash transfer to rehabilitate flood affected households, Zakat and Ushr that are levied on wealth and distributed to Muslims classified as “vulnerable”; Bait ul Maal, run on donor funds and distributed to the destitute; employee pension or retirement scheme stipends for primary and secondary education and madrassa school feeding programs.

-

b.

Private (given by NGOs): These pertain to services given by ‘Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund’, ‘National Rural Support Program’, ‘Sindh Rural Support Program’, ‘Sarhad Rural Support Program’, ‘Aurat Foundation’, ‘Edhi Foundation’, ‘INTERSOS’, ‘Save the Children’, ‘Plan International’, ‘National Commission for Human Development’, ‘Pakistan Initiative for Mothers and Newborns’ and ‘Thardeep’. These NGOs primarily provide healthcare, disaster risk management, and community development services as well as vocational training and microfinance access. It should be noted that these NGOs often reportedly collaborate with the Pakistan government.

Both types of SSNs were evaluated for impact as separate interventions which in turn were compared with each other.

Estimation model

For the purpose of this study, two binary logistic models were estimated as proposed by Becker and Ichino (2002). Logistic regression has been employed in the current study for empirical analysis because dependent variable was binary in nature. The predicted probability or output of logistic regression represents the probability of success of the category for which 1 is defined. In this study, treatment group is assigned 1 and 0 otherwise.

The treatment group in first model constitutes of households receiving public SSNs in the prior 12 months to the survey. While in the second model, it comprises of households receiving private SSNs in the form of training, physical goods, or other services from an NGO in the 12 months prior to the survey. The households are taken as unit of analysis in both the models.

Where: p(Xi) is the probability of receiving treatment, hence the propensity score, Di = 1 if the household has received SSN and 0 if otherwise, Xi is a vector of observational characteristics/covariates. The details of covariates are reported in Table A1.

All reported SSNs were considered in aggregate in the respective models as the number of households in the survey that were receiving SSNs was small to begin with and the aim of the study was to take on any possible effect under the broad categories of public and private SSNs. It was ensured that there was no overlap between the two groups; that is there was no household in the control group for the public SSN model that was receiving a private SSN and vice versa. Furthermore, households receiving both types of SSNs were excluded from the entire analysis.

Assistance from the community, relatives and Fitrana come under the heading of informal social protection. Although it is prudent to analyse such social safety nets as well it would be difficult to determine and justify the appropriate covariates to assess them as largely unobservable factors such as altruism determine the likelihood of a household to have received them. Therefore, households reported receiving such SSNs were also excluded from the entire analysis rendering the sole focus of this study to be a comparative study pertaining to the government and NGOs based SSNs. It was also ensured that the only households included in the analysis were those that reported experiencing a shockFootnote 2.

The covariates reported in Appendix (Table A1) are broad socioeconomic characteristics of households guided by the eligibility criteria of the various SSNs and the covariates chosen in similar studies. They are indicators of welfare. It is theorised that a less well-off household (as indicated by the covariates) will be more likely to receive an SSN. Indicators such as income and employment status were not included in the analysis as they are volatile in a rural setting. Furthermore, per capita consumption expenditure was also not included as there exist district-wise and province-wise price differentials that can lead to bias.

The predicted probabilities or the propensity score calculated from the model were then used to match treatment households with control households that had similar propensity scores. The matching algorithm chosen was Nearest Neighbour Matching (NNM)Footnote 3, which is as follows:

Where the set of control units C for the set of treatment units T is chosen in such a way that the absolute difference between the propensity scores for treatment unit i and control unit j is minimised. After it was ensured that the balancing hypothesis was held, the ATTs for the chosen outcome indicators were calculated through the following formula by specifying the outcome option when writing the psmatch2 syntax:

The ATT is the difference in outcome Y between a treatment unit i and its matched control unit j, where the latter is weighted by its propensity score. The summed differences are divided by the number of treatment units NT (the number of pairs). Because almost all outcome indicators are dummies, the number of the ATT itself cannot be interpreted; however, the sign and significance can be. If an effect is detected, then it can only be attributed to the SSN if it is statistically significant.

The outcome indicators examined in this study are given in Appendix (Table A2) showing detrimental shock coping strategies. In the survey households were asked about the three alternative ways to deal with the shock they experienced. The dummy variables were constructed in a manner that they took on the value “1” if the household had to resort to the respective strategy in any way. Theoretically, a household receiving an SSN should be protected from doing so. Hence, if the SSN is to be ruled as effective, the ATT for these indicators should be negative and statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Table 1 (panels A and B) shows the results for final binary logistic model for public and private SSNs that satisfies the balancing hypothesis.

The results from the logistic regression for house-hold owner ship are insignificant, however, the sign of this variable shows that house ownership increases the likelihood of a household receiving a public SSN. This can be because many of the households in the treatment group were recipients of the Watan Card, and eligibility criteria of Watan Card includes house ownership. The gender of the household head is insignificant; however, its magnitude and sign reflect that household with male head have higher chances of receiving the public SSN. This corroborates with the impact assessment of Watan Card which stated that female household heads were discriminated against to the point of exclusion from the program (UNHCR 2011).

If a member attempted to obtain a loan it increases the probability of receiving SSN. Age of household head is also positively related with probability of treatment: the higher the age, the more the likelihood. This is also corroborated by the statistically significant and negative coefficient of the squared term of the household head’s age which suggests that after a certain threshold age the likelihood of treatment begins to increase. This can be because public SSNs include employee pension and retirement scheme. An older household head is also likely to have a higher number of dependents which would prompt them towards attempting to receive or take up an SSN.

If a household belongs to Punjab it reduces the probability of receiving a public SSN. This is also a statistically significant variable. This can be explained by the fact that the rural areas of Punjab are more prosperous (due to the vibrant agricultural sector) as opposed to the rural areas in other provinces and are therefore less likely to have a vulnerable household that may be eligible for a public SSN. The coefficient for Sindh is positive and significant suggesting that if the household belongs to Sindh the likelihood of receiving the SSN increases.

Household size is a significant variable which is positively related to likelihood. A larger household is likely to have a higher number of dependents. Years of education of household head are positively related to likelihood (an educated household head is likely to be aware of SSNs and therefore opt for them), but is insignificant. The presence of a migrating family member is statistically significant and affects probability negatively. This could be since if a household is wealthy enough to aspire to better opportunities (and therefore not be likely to be eligible for the program) it has the capability to send a household member out of the village in search of opportunities.

Having a pucca /bricks house is negatively related to likelihood, which is expected, although this variable is statistically insignificant. Number of small animals is positively related, while number of large animals is negatively related; the more the large animals a rural household has, the more well off it is and less likely to receive a public SSN. These two variables are also statistically significant.

We reject the null hypothesis of joint insignificance of covariates as the associated p-value of the likelihood ratio test is 0.0000 which is less than level of significance. Therefore, the covariates are jointly significant in explaining a household receiving a public SSN.

Table 2 reports the average propensity score in the public SSN sample, which is 0.24, implying 24% of units in the sample received a public SSN.

As Table 3 shows, after restriction of common support, only 5 treatment observations were dropped which bodes well for the fit of the model.

After matching it can be seen in Table 4 that there has been a major bias reduction in many of the covariates. Besides the results reported in Table 5 for Rubin’s B and Rubin’s R are within the specified range. This leads us to conclude that sample is adequately balanced on the covariates.

The results for private SSN logistic model are given in Table 1B which shows that age of household head and the square of the variable are both statistically insignificant. The former is positive suggesting that the older a household head is the more likely the household is to receive a private SSN. The latter is negative suggesting that after a certain threshold of the household head’s age the likelihood of receiving the SSN increases. This is at odds with the fact that NGOs often give training and microfinance loans with a restriction on age favouring younger beneficiaries. The discrepancy can be explained by the fact that the age restriction is relevant to the recipient household member of the private SSN. In this case, data on the age of the recipient household member was not available, therefore it could not be included in the analysis.

Likelihood of receiving SSN increases if a household member attempted to obtain a loan as suggested by the statistically significant coefficient. The negative coefficient for electricity connection, albeit insignificant, suggests that a household without an electricity connection is more likely to be targeted by an NGO.

The coefficient for education of household head is significant suggesting that NGOs target relatively more educated households as they would have the capability to put training or an asset transfer to a productive use. Punjab has a negative and insignificant coefficient whereas it is positive and significant in the case of Sindh.

The results of estimation also show that having a pucca house decreases the likelihood of the household receiving a private SSN although the coefficient is statistically insignificant. For animal ownership results suggest that the larger animals that a household has the less likely it is to be targeted by an NGO as it is comparatively well off. The coefficient is also statistically significant. On the other hand, the smaller animals that a household has the more likely it is to be targeted by an NGO although the coefficient for this covariate is statistically insignificant.

Table 6 reports the average propensity score in the private SSN sample which comes out to be 0.084 implying 8.4 % units of the sample of the sample received a private SSN.

As shown in Table 7 only 3 of the treatment observations were dropped for not being on common support which bodes well for the fit of the model.

As can be seen in Table 8 matching reduced bias to a great extent for many of the covariates which infers that the matched sample is balanced on the covariates.

As shown in Table 9, the value of Rubin’s B is slightly higher than the recommended threshold, however, it does not render the results invalid because the joint bias is also statistically insignificant. We therefore conclude that the sample is adequately balanced for a meaningful analysis.

After matching, the ATTs for the respective SSNs were calculated, as given in Table 10.

For coping strategy indicators the results mostly have the desired negative sign (meaning that there were fewer instances of treatment units resorting to the coping strategy than their matched control group counterparts). Only in the case of private SSNs the results yielded a positive ATT for reduction in food consumption. This can be because while several of the NGOs covered in the study provide disaster relief services and also food for work programs most of them also provide training and infrastructure development which did not result in food security of the recipient households in the sample.

This, however, can be attributed to chance as the results are mostly insignificant and are statistically equal to zero. Being on the SSN did not effectively protect a household from resorting to the detrimental coping strategies. These results suggest that both type of SSNs, Public or Private, have mostly insignificant impacts on coping strategies. In case of shock a household receiving an SSN still had to resort to a detrimental coping strategy. In this regard, there was statistically no difference between the treatment and control groups.

However, public SSNs show a statistically significant impact on the strategy of switching to cheaper food; that is, there was a significantly smaller number of treatment units that had to resort to this strategy as compared to their matched control group counterparts. This can be due to the fact that many public SSN recipients reported having received the assistance in the form of food items, particularly wheat. Furthermore, the portfolio of SSNs as reported in the survey data also featured madrassa/school feeding program.

The results suggest that public SSN recipients are more likely to be food secure; in case of shock, they may have to reduce their food consumption, but they do not have to compromise the existing quality of their food. Receiving assistance in the form of food items seems to protect them for resorting to that strategy. These results further manifest the role of in-kind transfers in terms of food items (as given by Public SSNs) to contribute significantly towards the food security of shock facing recipient households.

Even though the food support program under Bait-ul-Maal was criticised for its inefficient targeting (World Bank 2013) the results of this study indicate desired protective impacts on the households that were reached by such programs. Furthermore, as seen in the case of BISP the main reported use of the transfer is expenditure on food and nutrition (Cheema et al. 2014).

The most insignificant impacts can be due to the fact that the SSN providers in Pakistan often have inefficient delivery mechanisms exacerbated by irregularities, extortion, leakages, duplication, and red tape (Jamal 2010). There is also a lack of cohesion between the providers. Furthermore, the size of the transfers themselves such as the monthly 1500 PKR given under BISP is often quite small to prompt a behavioral change (Nayab and Farooq 2012).

As far as outcome indicators of this study are concerned NGOs do not seem to show any protective effectiveness. However, as several of the NGOs reported in the survey are also microfinance providers which are often criticised for their lack of ineffectiveness in providing a cushion against shocks (Barrientos 2006), it is possible that the impact of private SSNs may be significant in other longer term outcomes such as adoption of riskier but more return yielding livelihoods by recipient household members. Examining such impacts is beyond the scope of this study. Additionally, SSNs are often politicised and for this reason they are not designed appropriately. Therefore, they are not effective in the achievement of goals that they propagate. (SDPI 2012).

Conclusion and policy recommendations

Various kinds of SSNs, provided by both Government and NGOs, have been operative in Pakistan for many years. However, it was the informal social protection system which had historically been more operative. Formal SSNs prominently entered the policy discourse of Pakistan with the advent of the food price hike of 2008 to protect the vulnerable segment of the population from landing in a worse-off position and relieving their short- term stresses. However, the existing literature in case of Pakistan is mostly narrowed to assessment of Public SSNs only, while relative effectiveness of Public versus Private transfers has not been studied. Besides, the existing literature pertains to the role of SSNs in mitigating the impact of shocks, however, a separate evaluation of public versus private SSNs was not conducted earlier. This study contributes to the literature by conducting a comparative analysis of relative effectiveness of Public versus Private SSNs for a developing country. Moreover, it also provides direction for the government and NGOs in devising SSNs for targeted groups as well as how to make them effective in terms of achieving the desired outcomes of increasing the welfare of the targeted groups. This study presents an evidence-based analysis that assesses formal SSNs in rural Pakistan on one of their intended preliminary outcomes; protecting vulnerable households from resorting to detrimental coping strategies in case of shock that undermines their existing living standard.

The results of the study suggest that both type of SSNs, public or private have mostly insignificant impacts on coping strategies. In case of shock a household receiving an SSN still had to resort to a detrimental coping strategy. There was statistically no difference between the treatment and control groups in this regard. However, public SSNs seem to have more protective effectiveness than private SSNs as the former shows a significant impact on one of the outcome indicators: the coping strategy of switching to cheaper food. When faced with a shock significantly lesser treatment units had to resort to this strategy as opposed to their control group counterparts. This may be due to the fact that many public SSN treatment households reported receiving the assistance in the form of food items. They may have to reduce food consumption but they are protected from comprising on the existing quality of it.

These results suggest that cash and in-kind transfers in terms of food items (as given by public SSNs) significantly contribute towards impacting the food security of shock facing recipient household. Apart from focusing on cash transfers policy makers and NGOs should explore the option of in-kind transfers as well. While designing programs robust needs assessments must be undertaken to identify local capacities of the community’s social risk management system so that such SSNs can be implemented which are complemented by it.

SSNs operative in Pakistan hold a comprehensive portfolio. However, as noted by Nayab and Farooq (2012) there is a lack of synergy and coordination between them. As suggested by the results of this study SSNs do hold potential for achieving their intended impacts. If public SSN providers collaborate with NGOs in terms of targeting, program design and service delivery, it is possible that they can have more significantly effective interventions.

Furthermore, strong monitoring and evaluation systems can ensure that service delivery is efficient at all implementation levels. If the programs (especially the ones rolled out nation-wide) are consistently assessed on objectively verifiable indicators, then they can be improved and enhanced well in time. The significance of the recommendations provided by this study are of paramount importance in the wake of recent disastrous floods in Pakistan. These recommendations can be taken as guidelines by both public and private sector SSN providers to mitigate the impact of shocks which are currently faced by the most vulnerable flood affected segments of population. Besides the public-private collaborative efforts to mitigate the impact of shocks, there is a dire need of sustainable solutions and management strategies. The sustainable solution to minimize these catastrophes lies in the effective enforcement of global environmental regulations along with the construction of dams, levees, and floodwalls that may reduce likelihood of flooding in the location of interest. Furthermore, a flood risk management strategy can reduce the risk for the people who are in flood prone areas. The flood risk management strategy should become an integral part of the national disaster management plan.

Currently NDMA is the national disaster management agency of the country and has a well-planned extensive NDMP (National Disaster Management Plan) for 2012–2022. This plan includes the disaster risk management risk approach along with disaster reduction measures and intervention strategies. However, the key issue is the effective implementation of those proposed measures. The effective implementation lies in the capacity and institutional strengthening of NDMA along with strong synchronization of all allied public and private institutions. Furthermore, the hazard forecasting and early warning systems need to be effectively operationalized and in the advent of disaster emergency plans should be executed swiftly. Moreover, some form of social insurance can be introduced in risk prone areas to mitigate the fiscal burden of rehabilitation. It has become even more important as the frequency and intensity of floods have increased in Pakistan.

Data availability

All data set analysed are included in paper.

Notes

The IFPRI survey could not cover Balochistan province due to security reasons

A limitation of this study is that the shocks module in the IFPRI survey questioned respondents on shocks experienced by the households in the last five years prior to the survey. Therefore, the validity of the results rests on the assumption that an adequate number of households in both the treatment and control groups experienced a shock 12 months prior, which coincided with the treatment households receiving an SSN. This can be supported by the fact that the most common shocks reported were flood related shocks (Nazli et al. 2012). A nation-wide flood occurred approximately 12 months prior to the survey.

With replacement and sort order set to random so that results can be replicated.

References

Adato M, Bassett L (2009). Social protection to support vulnerable children and families: the potential of cash transfers to protect education, health and nutrition. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 60–75

Aguero JM, Carter MR, Woolard I (2007) The impact of unconditional cash transfers on nutrition: The South African child support grant. International Poverty Center, Brasilia

Akter S, Alam MJ, Rahmatullah N, Ara (2014) Social safety nets and productive outcomes: evidence and implications for Bangladesh. USAID Washington DC

Alderman, H, Yemtsov R (2012) Productive role of social protection. Background Paper for the World Bank, 22

Baird S, Ferreira FH, Özler B, Woolcock M (2014) Conditional, unconditional and everything in between: a systematic review of the effects of cash transfer programmes on schooling outcomes. J Dev Effect, 1–43

Blattman C (2015) The winners and losers from the empirical shift in economics. Retrieved from Chris Blattman-International Development, economics, politics and policy: http://chrisblattman.com/2015/06/12/the-winners-and-losers-from-the-empirical-shift-in-economics/

Barrientos A (2006) Development of a social protection strategy for Pakistan. Institute of Development Studies, Sussex

Becker SO, Ichino A (2002) Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The Stata Journal 358–377

Chininga B (2005) Targeting safety net intervention in developing countries: some insights from a qualitative simulation study from Malawi. The Eur J Dev Res 17(4):706–734

Cheema I, Farha M, Hunt S, Javed S, Pellerano L, Leary S (2014) Benazir Income Support Programme: First follow up impact evaluation report. Oxford Policy Management, Oxford

Cowen T, Tabarrok, Alex (2012) Modern principles of economics. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Devereux S (2002) Can social safety nets reduce chronic poverty? Development Policy Review, 657–675

Gilligan DO, Hodinott J, Kumar N, Taffesse AS (2009) Can social protection work in Africa? evidence on the impact of ethiopia’s productive safety net programme on food security, assets and incentives. IFPRI Washington DC

Galasso E, Ravallion M (2003) Social protection in a crisis: Argentina’s plan jefes y jefas. The World Bank, Washington, D.C

Haan AD (2014) The rise of social protection in development, progress, pitfalls and politics. Eur J Dev Res 26:311–321

ILO (2015) Social protection—building social protection and comprehensive social security systems. Retrieved from International Labour Organization Geneva

ILO (2019) Mapping social protection systems in Pakistan. Retrieved from International Labour Organization Geneva

ILO (2021) A social protection profile of Pakistan. Retrieved from International Labour Organization Geneva

Iqbal T, Padda IH, Shujaat F (2020) Sustainable impacts of social safety nets: the case of BISP in Pakistan, Pakistan. Journal of Applied Economics 30(2):153–180

Jamal H (2010). A profile of social protection in Pakistan: An Appraisal of Empirical Literature. Social Policy and Development Centre Research Report no. 81. SPDC, May

Lustig NC (2001) Shielding the poor - social protection in the developing world. Brookings Institution Press, Washington DC

Morduch J, Sharma M (2002) Strengthening public safety nets from the bottom up. The World Bank, Washington DC

Munro LT (2005) A social safety net for the chronically poor? Zimababwe’s public assistance program in 1990s. The European Journal of Development Research 17(1):111–131

Naqvi SM, Sabir HM, Shamim A, Tariq M (2014) Social safety nets and poverty in Pakistan (A case study of BISP in Tehsil Mankera District Bhakkar). J Finance Econ 2(2):44–49

Nayab DE, Farooq S (2012) Effectiveness of cash transfer programmes for household welfare in pakistan: the case of the benazir income support programme. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics: Poverty and Social Dynamics Paper Series, 1–31

Nazli H, Haider SH (2012) Pakistan rural panel household survey 2012 (Round 1)—methodology and community characteristics. International Food Policy and Research Institute, Washington DC

Nazli H, Haider SH, Hausladen S, Tariq A, Shafiq H, Shahzad S, Mehmood A, Shahzad A, Whitney E (2012) Pakistan rural household panel survey (Round 1): household characteristics. IFPRI, Islamabad

Rahman HZ, Choudhury LA (2012) Social safety nets in Bangladesh - ground realities and policy changes. Power and Participation Research Centre Bangladesh

Ravallion M (2003) Assessing the poverty impact of an assigned programme.” in the impact of economic policies on poverty and income distribution: evaluation techniques and tools, by Francois Bourguignon and Luiz Pereira da Silva. Oxford University Press, New York, p 103–119

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55

SDPI (2012) Demand for universal social security - SDPI in the Press. 20 November. http://www.sdpi.org/media/media_details895-press-2012.html

Soares FV, Ribas RP, Osório RG (2010) Evaluating the impact of Brazil’s Bolsa Familia: Cash transfer programs in comparative perspective. Latin American research review 45(2):173–90

Toor IA, Nasar A (2004) Zakat as a social safety net: exploring the impact on household welfare in Pakistan. Pakistan Economic and Social Review 87-102

UNHCR (2011) The watan scheme for flood relief: protection highlights 2010‐2011. UNHCR Geneva

World Bank (2013) Pakistan: towards an integrated national safety net system. World Bank, Washington DC

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naveed, S., Malik, A.I. & Adil, I.H. The role of public versus private social safety nets in mitigating the impact of shocks in rural Pakistan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01570-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01570-9

- Springer Nature Limited