Abstract

Despite its positive effects on physical activity promotion, the motivational style of interaction by health professionals is not easily taken up, as shown by meta-analyses of training courses. The concerns professionals experience for taking up novel skills remain an open question. Preservice physical education teachers were offered a 16-h training course on motivational interaction, an approach to teacher–student interaction based on the synthesis of self-determination theory and motivational interviewing. This study investigates what benefits and concerns pre-service PE teachers experience when trying to adopt this new style of interaction and use its specific techniques. Individual interviews (N = 19) of pre-service PE teachers were conducted after the training course. The narrative approach was first used to analyse participants’ experiences of using motivational interaction. Two types of storylines emerged, one enthusiastic and optimistic and the other one partly reluctant. Concerns and benefits of using specific techniques were then selected as suitable units of analysis and inductive content analysis was employed to further analyse the units. The analysis process included open coding, creating categories, and abstraction. Participants described positive professional transformation through learning motivational interaction. Expressed benefits included reducing conflicts and developing good relationships. Participants also voiced concerns that were grouped under four categories: (1) problems in delivering the techniques in group situations, (2) mismatch with professional role demands, (3) undesired effects on personal interaction, and (4) target behaviour (technique-) related concerns. These overarching categories covered a variety of concerns, e.g., losing control of situations, and the challenge of allocating time and feedback equally among students. To successfully uptake style and techniques of motivational interaction, pre-service teachers may have to re-evaluate their role and the power relations within the target group. Utilizing the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability, we discuss how interaction training can address experienced concerns in order to improve the delivery, effectiveness, and acceptability of such training programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Compelling evidence suggests that teachers’ interaction style influences students’ motivation, well-being, and engagement in school (McQuillin and Lyons, 2016; Reich et al., 2015), and can also increase their physical activity (PA) (Ng et al., 2012; Teixeira et al., 2012; Van Doren et al., 2021). However, despite proven improvements in interaction styles after motivational interaction training, most trainees fail to achieve the desired skill levels or do not put the skills into practice (de Roten et al., 2013; Hall et al., 2016; Madson et al., 2009). This article investigates the uptake of motivational interaction skills in the context of one particular professional group, pre-service physical education (PE) teachers. The implementation of evidence-based motivational interaction is an emerging area in PA research. By adopting an optimally motivating style, teachers can foster students’ autonomous motivation and help to tackle the widespread problem of physical inactivity with its many serious health consequences (Hagger and Chatzisarantis, 2016; Lee et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2012; Teixeira et al., 2012; Van Doren et al., 2021).

This research is based on a large intervention study, the Let’s Move It trial (LMI; Hankonen et al., 2020), which drew on both self-determination theory (SDT, a theory of the causes, processes, and outcomes of human motivation; Ryan and Deci, 2020) and motivational interviewing (MI, a widely adopted individual and group counselling approach for promoting motivation for behaviour change; Miller and Rollnick, 2013). The LMI intervention model synthesized the elements of the two approaches into 10 interaction principles that the intervention facilitators used in sessions directed toward increasing adolescents’ PA. These principles were condensed into seven practical techniques included in the curriculum of the motivational interaction course offered to pre-service PE teachers. Their selection was based on (1) their feasibility in the school context, (2) the empirical support of their effectiveness, and (3) they fitted together based on theoretical considerations. Table 1 demonstrates how the techniques of motivational interaction taught in this course (column 1), can be mapped onto the corresponding MI (Hardcastle et al., 2017) and SDT (Teixeira et al., 2020) technique taxonomies (columns 2 and 3).

SDT claims that for motivation to predict outcomes, the quality of a person’s motivation is more important than its amount. According to SDT, nurturing the basic psychological needs of autonomy (sense of volition), competence (sense of mastery and efficacy), and relatedness (sense of caring relationships) fosters autonomous and internalized motivation. A teacher’s interaction style can either nurture or thwart basic psychological needs and has been shown to be linked to student motivation (Aelterman et al., 2019). Autonomy-supportive interaction includes tangible acts of instruction, such as adopting the students’ perspective, allowing enough time for learning, providing explanatory rationales, relying on non-controlling language, and acknowledging and accepting expressions of negative affect (Reeve and Halusic, 2009). To structure students’ learning activities teachers can use, for instance, goal clarification and process feedback. It has been shown that goals and process feedback relate to the need satisfaction of competence (i.e., feelings of efficacy and mastery) (Aelterman et al., 2019; Mouratidis et al., 2013), autonomy (i.e., feeling of being in charge of their learning process), and relatedness (i.e., sense of caring and positive classroom atmosphere) (Krijgsman et al., 2019).

A related approach, MI (Miller and Rollnick, 2013) was initially developed for clinical work with clients in need of behavioural change, but nowadays it is also applied in many other motivationally challenging areas, for instance in assisting teachers to use a more motivating style of interaction with students (Rollnick et al., 2016). MI emphasizes collaboration, acceptance, evocation, and compassion as the basic ingredients of the MI Spirit. The core skills of MI are asking open questions, affirming, reflective listening, summarizing, informing, and advising with permission (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). MI is becoming increasingly popular in practically all health and exercise settings, and it plays an important role in helping people change PA behaviours (Hilton and Poulter, 2008). Empirical evidence shows that MI interventions are more effective than standard counselling in a variety of health behaviours, for instance, in promoting PA (Frost et al., 2018; Markland et al., 2005).

In education, the practice of MI is relatively new but it has integrity with pedagogical practice (Wells and Jones, 2018) and several writers (e.g. Sheldon, 2010; Shepard et al., 2014) have outlined the use of MI in this setting. MI can be used to help students to identify and achieve their goals as well as to address bullying, work with at-risk students, and re-engage dropouts (Pignataro and Huddleston, 2015; Wells and Jones, 2018). It can promote academic performance and student engagement by creating a collaborative and empowering learning environment (Sheldon, 2010; Wells and Jones, 2018). SDT and MI are compatible: SDT’s theoretical focus on need support is consistent with the key features and techniques of MI (Markland et al., 2005; Vansteenkiste and Sheldon, 2006). MI principles might help to provide new insights into the concrete application of SDT’s theoretical constructs (Patrick and Williams, 2012), while SDT offers a theoretical explanation for why MI works (Vansteenkiste and Sheldon, 2006).

Previous studies suggest that it is essential to provide practice opportunities and feedback for MI trainees to find a way to translate theory into practice (Goggin et al., 2010). Similarly, in a study of SDT-based training, PE teachers reported appreciating collaboration with other training participants and the possibility to apply the proposed strategies in their work (Aelterman et al., 2013). A recent study (Hancox et al., 2018) grounded in SDT explored group exercise instructors’ experiences and found four challenging themes when implementing motivational strategies: the structured nature of the group exercise class, initiating meaningful one-to-one conversations, phrasing instructions in a need-supportive way and breaking old habits. Previous qualitative research also shows that teachers feel more familiar with structuring strategies such as offering help and providing positive feedback, but the concept of autonomy support is relatively new to them (Aelterman et al., 2013, 2016; Reeve, 1998) and they may find it challenging to offer choice in a need-supportive way (Hancox et al., 2018). Thus, it appears that some of the techniques of motivational interaction are more difficult to apply.

Taken together, research on SDT-based training indicates that teachers can adopt various behaviours that support autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their PE classes (Aelterman et al., 2014; Cheon et al., 2012; Su and Reeve, 2011), but research on MI-based training suggests that the level of skill adoption could be improved among clinicians (Hall et al., 2016) and trainees learning MI mainly for substance use disorder treatment (Schwalbe et al., 2014). Within education contexts, most of the previous studies examining the translation of SDT and MI into practice have been conducted among in-service teachers. However, the adoption of motivating behaviours may be at least equally important for pre-service teachers, as they have not yet developed strong habits in everyday teaching practice. The research project at hand was designed to provide pre-service teachers with a university-level in-depth course on motivational interaction and evaluate it. It is crucial to teach motivational interaction already at the phase in which pre-service teachers are in the process of learning their profession and professional role. Adopting good interaction habits from the very beginning is important as replacing old habits is known to be challenging (Hancox et al., 2018).

To overcome the gap between training and practice, it would be important to understand the experiences of trying to use motivational interaction. We first explored these experiences based on narrative analysis. Two types of storylines emerged, one optimistic and the other one partly reluctant. We then refined the research question to focus on the observed benefits and concerns of using the proposed interaction techniques. We asked: what benefits and concerns do pre-service PE teachers experience when trying to adopt motivational interaction and use its specific techniques?

This study aims to identify and better understand these benefits and concerns—which reflect the acceptability of the interaction techniques and act as facilitators and barriers to their uptake in professional practice. It takes a closer look at the benefits and concerns that participants experience when trying to implement motivational techniques in their interaction and utilizes Sekhon’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (Sekhon et al., 2017) when discussing the findings. According to this framework, acceptability is one key concept in predicting intention to engage with the intervention, and it is thus a necessary condition for a successful and effective implementation of the motivational interaction.

Methods

Recruitment, participants, and intervention

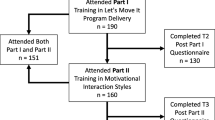

Pre-service PE teachers were informed via email about an optional, advanced-level course on motivational interaction at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Two courses were delivered, one during the autumn semester of 2017 and the other during the spring semester of 2018. Both courses had the same content. Fourth- and fifth-year students (total n = 114) were eligible to choose this optional course and 30% (n = 35) chose it. In the autumn, 23 pre-service PE teachers started the course and 22 of them completed it. In the spring term, 12 pre-service teachers started the course and 11 completed it. They were relative novices in the area of motivational interaction, but they had all also attended a previous compulsory course on general interaction skills.

The course objective was to train pre-service PE teachers in motivational interaction with their students. Through interactive exercises, discussions, and practical examples, the participants were familiarized with the theoretical frameworks (MI & SDT), concepts of motivation, basic psychological needs, and the techniques of motivational interaction (Table 1). All the participants tried out the suggested techniques during the course in practice and as homework, they chose 1–3 techniques and kept a diary about their experiences of using them. All interviewees described that they used the techniques in their teaching while some (4 interviewees) did their homework task with their friends, colleagues, or family members because they did not have any teaching during the week, they had the homework. The full course content is shown in Additional file 2.

The courses were taught by the same project coordinator who had substantial experience in piloting the courses in other contexts. The courses were delivered face-to-face in a group and consisted of four lessons and 16 contact hours. To obtain rich data on course participants’ experiences, all participants were offered a chance to participate in the study. They were briefly informed of the study by the project coordinator during the first lesson. During the second lesson, they received a letter with more information about the study. Between the second and third lessons, the participants were given the opportunity to express their interest in participating in the study by entering their contact information onto an electronic form. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time during the study. Data was handled confidentially, and stored in a secure, password-protected location. Anonymised data has been made available for other researchers via the Finnish Social Science Data Archive. The study protocol was reviewed by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences.

Data collection

All the participants who signed up for the study were interviewed (total n = 19) a few days to 6 weeks after the course. 14 interviewees were female, and 5 were male. The semi-structured individual interviews lasted 26–68 min and were carried out by two researchers who were not involved in the course implementation. The two interviewers were both female academic research fellows from non-PE teacher backgrounds. They had no personal familiarity or experience with PA promotion and were unfamiliar with the specific experience under study. These researcher positionalities undoubtedly had an influence on what the interviewees wanted to tell during the interview. The majority (16) of interviews were conducted face to face in the premises of the xx Faculty (participants’ studying space where the interviewees were invited in as researchers). A few (3) interviews were conducted online, as this was more convenient for some participants. At the beginning of each interview, the procedure and the purpose of the interview were explained. A topic guide (see https://osf.io/5z9gq) ensured consistency across the interviews. The main themes of the interview were (1) the experienced content of the training, (2) the feasibility and perceived effectiveness of the motivational interaction techniques, and (3) additional support for behaviour change (any means employed to support the use of motivational interaction). The interviewer emphasized that the course teacher would not hear the individual comments made by the participants. All interviews were recorded using an audio recorder and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The analysis was conducted by the first author using an iterative approach: Formative steps informed later steps. A narrative approach was first employed (see e.g. Polkinghorne, 1988) to study participants’ experiences of using motivational interaction. This involved reading the transcribed descriptions of the participants’ experiences multiple times considering the kind of context and situations to which they related. Two types of storylines emerged, one enthusiastic and optimistic and the other one partly reluctant. This initial reading already revealed that some of the techniques of motivational interaction raised more concerns than others. As the understanding of the phenomenon grew, the research question was shaped and crafted. Concerns and benefits of using specific techniques were selected as suitable units of analysis.

The systematic analysis of these units focused on both manifest and latent content. As in the inductive content analysis generally, the analysis process included open coding, creating categories, and abstraction (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). The concerns and benefits participants attached to different techniques were first identified. Second, the codes were organized into categories by grouping similar concerns and benefits. All the benefits and concerns expressed fit into these categories. Finally, the abstraction phase included interpreting the meaning of the categories and examining their inter-relationships. In this phase, it appeared that the benefits were closely related to the purpose of each technique (for instance, the benefit “opening new doors and directions” was attached to “empathizing and reflective listening” and “open questions and interest”). The concerns, on the other hand, were related to different overarching categories that captured the meaning and association between the concern categories. To enhance the trustworthiness of data analysis the research team was constantly consulted to discuss the content of the categories and the credibility of the analysis. The academic background of the research team guided the research process from the conceptualization of the research questions to the interpretation of the results (for instance, relating the participants’ concerns to the subdimensions of acceptability). In analysing the interviews, we engaged in rigorous analysis and put ourselves in the role of learner. Since we aim to improve the course content, we will primarily focus on the experienced problems and try to propose some means to solve them.

The current reporting of this study conforms to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (see Additional file 1).

Results

Analysis of the perceived benefits

Generally, the interviewees regarded each of the motivational techniques as important and tangible tools and as representing the emotional, interactive, and motivational skills that were considered important for both the teaching profession and life in general. The interviewees saw the use of different techniques as intertwined and argued that the use of motivational interaction might create a positive transformation in professional practice.

R10: It’s really good that we’ve had this course, and at the same time the practice, so I have noticed that also in the PE lessons there are so many other goals than just the official ones, there are emotional or social interaction goals as well, so I’ve been thinking: what would be more sensible and more functional way, especially from the point of view of motivation, so that it’s not just doing some exercise, but especially having been thinking the reasons behind it, why are we doing it, and also thought it from the point of view of interaction.

All the techniques were experienced as functional when they were applied correctly in the appropriate situations, and their use was considered to have numerous benefits.

R1: I think they’re definitely good and practical when you know how to use them right so that you know how to use them at the right moments in the right way… I would buy into all of them.

The categorized (see pp. 10–11) benefits per technique are summarized in Table 2. In sum, the benefit categories were closely related to the functions which the techniques were supposed to have, and which were taught during the course. For instance, positive feedback and appreciation were experienced to reduce conflicts, develop good relationships, create a feeling of being heard, and increase motivation.

R1: I really strive for to give positive feedback and encouragement and all that, and that I show my students that I appreciate them so that they can also appreciate and respect me, so my experience is that positive feedback is something that creates a good atmosphere, and with a positive attitude learning also happens and that supports my goals as well as the student’s goals.

R2: So if the teacher approaches the situation like “Just shut up and do something” and “Why aren’t you doing anything” and so on, then students react like “Blah, blah, blah, I don’t care”, but when you can approach it like “Hey, I know you can do this” so that you show appreciation, even if you have to stay strict.

Analysis of the concerns

Along with the benefits, however, the interviewees also raised concerns about using the techniques. These were related to four different categories: (1) problems in delivering the techniques in group situations, (2) mismatch with professional role demands, (3) undesired effects on personal interaction, and (4) target behaviour (technique-) related concerns. In the following, we will present findings concerning each technique per category.

Problems in delivering the techniques in group situations

Most of the techniques were considered challenging in a group situation. Utilizing ‘empathetic and reflective listening’ was seen as a demanding time, which for a teacher is a very limited resource. Concentrating emphatically and reflectively on one student at a time was seen to take time from both the lesson activities and other students: “There is no time to sit there chatting with them, you would have to chat with them all day, and then the other twenty-four would suffer because that one student gets so much attention.” (R2)

The busy school environment also raised concerns about utilizing the technique of ‘understanding resistance and speaking in a non-controlling manner’. Some interviewees considered it unsuitable for situations in which one needs to react quickly to an emerging conflict.

R16: You must, for example, separate the two who are fighting, and then maybe later in a conversation you can […] try to understand the resistance and somehow speak in a non-controlling manner. But sometimes you might have to speak in a way that is a little more controlling.

As for ‘providing structure and rationale’, concerns arose as to whether this technique would be practically adaptable to PE lessons which were regarded ideally as relatively free periods within the highly structured school day, serving the function of recovery.

R12: It is somehow nice that it’s not too structured, if you think about the whole… school day, then the PE class could be that one moment when you can release those…] energy levels and get to just do things.

The interviewees considered ‘advising without pressing’ to be suitable mostly for one-to-one tutoring situations but not so much for group situations where it is seen as “a little challenging, but then if you turn it into personal training then it could probably be more suitable (R3).”

In group situations, concerns about ‘giving positive feedback and appreciation’ were related to allocating positive feedback equally. “R4” comments: “Whether positive feedback is always given to that particular person, or whether you remember to give it to everyone.”

Mismatch with professional role demands

The worries related to the roles in the school were especially prominent in the experiences of four techniques: ‘understanding resistance and using non-controlling language’, ‘advising without pressing’, ‘providing choice’, and ‘giving positive feedback and appreciation’. The main difficulty in using these techniques was that they were not considered suitable for a person who is supposed to give instructions. For instance, ‘advising without pressing’ was considered problematic due to the teacher’s role of giving advice: “If a teacher starts to ask permission to give advice that will not work in the school environment; the teacher is there to give advice and to teach and help students.” (R2)

Providing choice raised similar concerns about losing control. In these comments, the teacher was seen as a person who should be in charge of what happens during the lesson. The interviewees also pondered on the balance between the number of choices offered and control.

R4: …in basketball, I had decided that we would select the teams like this and have the court like that, and they had comments like “why can’t we choose them ourselves” and “why is the court like this”. Then I started to think that am I losing control here, like am I marching to the beat of their drum…how much autonomy is enough… and to what extent is it good to be flexible?

Providing choice and giving positive feedback was seen by some as a disservice to the students, as later they would need to be able to function in the real world, where they do not always have a choice and everything is not positive. Giving positive feedback was also regarded as weakening students’ ability to receive constructive criticism: “In my opinion, the children also have to face situations in which everything is not always good and great and positive…at least for our generation, the ability to take constructive criticism is something that is greatly lacking.” (R5)

Undesired effects on personal interaction

Many of the concerns dealt with interaction situations and the resulting feelings. Participants felt that using some of the techniques could seem foolish, forced, or patronizing; choosing the right words might be difficult and the interaction might become awkward. These worries were associated with almost all the techniques. The participants worried that with both ‘empathetic and reflective listening’, and ‘open questions and interest’, the other person might be reluctant to self-disclose. In such a situation, some of them thought that open questions and listening would serve no purpose: “And at times, I’ve also noticed that something like empathetic listening will not work at all. That no matter how much you try to listen and so on, the other person will not give you anything.” (R16)

Interviewees also said that paraphrasing someone’s words by repeating back what they just said felt awkward. However, some interviewees had good experiences with this.

R7: Will the other person not feel that it’s silly that I just keep repeating what they said? But […] when I tried it a few times, no one told me to be quiet, or that I sounded like a fool or anything, but somehow it has that kind of vibe.

Concern over choosing the right words arose about ‘forming open questions’ and ‘speaking in a non-controlling manner and understanding resistance’. How to best structure the intended message was seen as something that requires patience and consideration. “R1”: “Finding the right questions and presenting them takes practice. Of course, you can come up with questions, but how to formulate them so that they would actually be of help.”

‘Giving positive feedback and showing appreciation’ was seen as sometimes leading to awkward situations. Receiving positive feedback is not easy or enjoyable for everyone.

R12: To me, positive feedback brings to mind this one (personal training) client…with whom I came close to a conflict when I gave him/her too much positive feedback. That this atmosphere of “well done, well done” would not help motivate them at all.

Target behaviour (technique-) related concerns

Some of the worries were associated with target behaviour-related concerns and felt limitations of the motivational interaction techniques. In ‘providing choice’ the perceived problem was the appropriate amount of choice. Offering multiple options was considered laborious; giving just a few different choices, in turn, was seen as sufficient because “then it’s possible that no one can decide, so then it’s good to give, like, only a couple of alternatives they can choose from, and then it’s kind of easier (R6).”

It was also feared that if choices were offered, the one making the choice would try to choose the easiest option: “R12”: “People are typically like that, myself included, they’ll try to take the easy way out.”

The difficulty of always finding something positive in whatever the students do arises in relation to ‘giving positive feedback and appreciation’. It was agreed that it should not be forced and that it was only beneficial when it was specific enough.

R4: When someone is really disturbing the class, (claiming) that “this is stupid”, should you then be like “hey, it’s great that you are voicing your opinion”? R11: It can’t be just “good, good, great”. For the student to be able to develop, you have to say what it is that is good, and why it is so good.

Discussion

This study explored pre-service teachers’ experienced benefits and concerns of using motivational interaction in practice after a training course. The results construct a rich description of the complex phenomenon; of learning to implement motivational interaction in PE. First, it is notable that the expressed benefits and concerns are linked to the teacher’s role and obligations as a PE specialist. The results reveal that some of the techniques (especially ‘providing choice’ as well as ‘understanding resistance and using non-controlling language’) are feared to entail letting go of the traditional teacher expert stance, to undermine the teaching structure thus leading to chaos. These concerns partly question the suitability of motivational interaction for teaching. They are in line with the findings of Aelterman et al. (2019), according to which teachers often believe that too much support for autonomy results in demotivating chaos. It displays the common misunderstanding that teachers have all the knowledge needed to get some organized action going in the class. This approach is not, however, the best possible way to activate the students’ motivation, interest, and resources for PA.

Interestingly, the benefits and concerns found in this study link to the antecedents of need-supportive and controlling styles (Matosic et al., 2016). For instance, the concerns about group situations were mostly related to external pressures (e.g., time management of empathetic and reflective listening) and the worries related to the roles of social–environmental factors (e.g., a cultural norm that the teacher’s role is to be in charge and give instructions, not to offer choice). Furthermore, the concerns that dealt with the unwanted effects of interaction were partly based on perceptions of subordinates’ behaviours and motivation (e.g., perceptions of students’ ability to receive positive feedback). Taken together, the results imply that adopting a new style of motivational interaction can be challenging since it contrasts with the traditional expert model that the pre-service PE teachers were familiar with. The application of motivational interaction style might create transformation in professional practice (Howard and Williams, 2016) and change ways of thinking (Söderlund et al., 2008).

Similar roadblocks to adopting the basic ideas of MI have been recognized before. The expert trap is a typical MI roadblock (Miller and Rollnick, 2013): the professional assumes the expert role, providing direction and giving advice, rather than reflecting on the client’s thoughts about their plans and goals. This invites passivity and dependency, deflates self-confidence, and reduces the likelihood that clients will engage in the change process (Breckon, 2015; Miller and Rollnick, 2013). The PE teacher’s primary goal is to enhance students’ autonomous motivation for PA, and the Expert trap may endanger reaching this goal. This trap can be avoided in group settings by creating a partnership atmosphere and focusing on collaboration (Velasquez et al., 2006).

Second, the benefits and concerns appear to link the experienced usability of the motivational interaction techniques to acceptability. Intervention acceptability is a necessary precondition for an intervention to be successfully implemented and effective. According to the theoretical work of Sekhon et al. (2017), acceptability consists of seven component constructs: (1) Affective attitude, (2) Burden, (3) Ethicality, (4) Intervention coherence, (5) Opportunity costs, (6) Perceived effectiveness and (7) Self-efficacy. Many of the identified benefits and concerns seemed to relate to these seven subdimensions.

The participants’ concerns relate to all the subdimensions of acceptability. (1) Affective attitude (how an individual feels about the techniques) was present in the sceptical stance towards specific techniques of motivational interaction. Similar doubts have been recognized before e.g., concerning how to offer choice in a need-supportive way (Hancox et al., 2018). Concerns were also related to (2) burden (the perceived amount of effort needed to use the specific technique), especially in relation to time management. Interestingly, several concerns were linked with (3) ethicality (techniques fit with an individual’s value system as a teacher rather than as a private person). For instance, to behave ethically a teacher should allocate their time and feedback equally. Concentrating on one student was seen as taking resources away from other students. These time management and equality-related concerns highlight that the participants experienced challenges in using motivational interaction in a group context even while the literature suggests that techniques of motivational interaction can be successfully applied in group situations in educational contexts (see e.g., Cheon et al., 2012; Wells and Jones, 2018). On the other hand, ethicality was also linked with the worries about the teacher’s role and responsibility to prepare students for the real world, and to tolerate situations with no choices and no positive feedback.

The worries about (4) intervention coherence (the extent to which participant understands the techniques and how they work) were mostly due to misinterpretations. It is essential to address these misunderstandings to avoid them in the future (see Table 3 for detailed suggestions). Many concerns considered (5) opportunity costs (the extent to which benefits, profits, or values must be surrendered when using the techniques) in the form of losing control and authority. These concerns link to a mix-up with autonomy support and chaos which has been recognized also in previous studies (Aelterman et al., 2019). (6) Perceived effectiveness (the extent to which the techniques are perceived as likely to achieve their purpose) was present in the sceptical stance toward the effectiveness of using the techniques in the school environment. This is interesting since it has been shown that both MI (Sheldon, 2010; Shepard et al., 2014; Wells and Jones, 2018) and SDT (Aelterman et al., 2019; Krijgsman et al.. 2019; Mouratidis et al., 2013) have integrity with pedagogical practice and it is vital for students’ motivation, well-being, and engagement to encounter them with a supportive and empowering interaction (McQuillin and Lyons, 2016; Reich et al., 2015). (7) Self-efficacy (the participant’s confidence that they can perform the behaviour(s) required for the implementation of the techniques) concerns were evident in the challenges of choosing the right words and deciding what amount of choice was appropriate. These concerns are in line with previous research (see e.g., Hancox et al., 2018) and they highlight the importance of supporting training participants’ need for competence (i.e., feelings of efficacy and mastery) (Aelterman et al., 2019; Mouratidis et al.. 2013) in these areas.

The benefits identified by the teachers were mostly related to affective attitude (how an individual feels about the techniques) and perceived effectiveness (the extent to which the techniques were seen as likely to achieve their purpose).

Practical implications

As noted above, the concerns were partly based on misunderstandings of issues discussed already during the course. Table 3 summarizes the concerns and provides practical suggestions on how to respond. As part of discussing the results, our research team formulated these suggestions based on the research literature and practical guidelines of SDT and MI (e.g., Miller and Rollnick, 2013; Rollnick et al., 2016; Rosengren, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2020). The school environment-related concerns emphasized time management issues and questioned the usability of some techniques in the constantly changing situations in PE lessons. Providing concrete examples of how to apply motivational interaction in these situations is advisable. For instance, paying attention to all the participants, supporting their self-efficacy, and providing empathy are also possible in fast-changing group situations.

The concerns related to the problems in delivering the techniques in group situations and to the mismatch with professional role demands were mainly based on misunderstandings such as the belief that providing choice would lead to loss of control and supporting autonomy could lead to excessive permissiveness and demotivating chaos. In these situations, it would be important to re-emphasize that offering autonomy or using non-controlling language does not exclude structure; but need-supportive interaction requires them both (Aelterman et al., 2019). Well-structured learning environments provide goal clarification and process feedback and, generally, more goal clarification and process feedback relate to more competence, autonomy, and relatedness satisfaction (Krijgsman et al., 2019).

The worries concerning the undesired effects on personal interaction often involved the dynamics of interaction and the feelings that this led to. As in Hancox et al. (2018), phrasing instructions in a need-supportive way was sometimes experienced challenging. It is therefore essential to think not only about what to say but also about how to say it. According to Miller and Mount (2001), learning motivational interaction involves not only learning preferred behaviours but also unlearning non-preferred behaviours. This can take some time, and clumsiness is unavoidable in the beginning.

Of the target behaviour (technique-) related concerns, a central one concerned the principle of providing choice (see e.g. Hancox et al., 2018). Teachers can promote choice and initiative in various ways. Previous studies suggest that offering choice in PE lessons can increase levels of in-class PA (Meng et al., 2013) and students often interpret the provision of choice as acceptance of them as individuals with different talents and skills (Wallace and Sung, 2017). Sometimes it is good to begin inside one’s comfort zone so that successful experiences ease the leap toward more challenging options. However, in this study, the interviewees regarded offering choice as demanding for fear that students would only choose easy options without challenging themselves. The interviewees also pondered which amount of alternatives would be appropriate. This is a relevant question in relation to other techniques as well. For instance, it has been shown that goal clarification and process feedback seem to build on each other’s positive effects. However, when perceiving very high levels of process feedback, additional benefits of goal clarification were no longer evident (and vice versa) (Krijgsman et al., 2019).

The results provide suggestions on how to adjust the training in the future. Pre-service teachers’ experienced benefits and concerns of using motivational interaction highlight the embeddedness of participants’ social environments (group situations, professional role demands, personal interaction, and target behaviours in their contexts). Future training should take this social embeddedness into account and encourage participants to self-set their goals that fit their own context and engage their social environment in the change process. We report elsewhere the systematic development of a theory-based intervention to teach motivational interaction techniques to PA and sports professionals (see https://osf.io/bgwma/). This optimization process explicitly focuses on how behaviour change and self-regulation strategies such as planning (see e.g., Rhodes et al. 2020) and a set of habit-forming and breaking skills (see e.g., Potthoff et al., 2022) can be used to foster participants’ individual motivational interaction behaviour change processes in their unique contexts.

Limitations and reflections

Previous literature indicates that teachers motivating styles have implications for future students’ PA both in and out of school (Ng et al., 2012; Teixeira et al., 2012; Van Doren et al., 2021). However, it is important to note that autonomous motivation toward activities in PE predicts autonomous motivation toward PA outside of school which associates with self-reported PA, but not objectively measured PA (Hagger and Chatzisarantis, 2016).

This study focused on the benefits and concerns pre-service PE teachers’ experience when trying to adopt motivational interaction style and use its specific techniques. It can be argued that focusing too much on interaction techniques can lead to losing sight of spirit and style (cf. Rollnick and Miller, 1995). However, according to our results, the experiences of the changes in the style of interaction and learning of the specific techniques were seamlessly interconnected: Practicing the use of specific techniques was seen to lead to a gradual change in interaction style. Besides, not all the techniques of motivational interaction raised similar concerns. Future research should study whether the antecedents (see Matosic et al., 2016) of using the techniques also differ.

As the interviews took place over a time span of a few days up to six weeks after the course, the interviewees’ timeframes to practice the techniques of motivational interaction after the course differed considerably. However, all the interviewees had already tried them out in practice during the course.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the emerging literature on how to best facilitate the uptake of motivational interaction in daily professional practice. This style of interaction may require the willingness to adopt a new professional role and to build more person-centred relationships based on partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation (Miller and Rollnick, 2013, pp. 14–24). Adopting a new way of thinking can be challenging since motivational interaction contrasts in some respects with the traditional expert model that the pre-service PE teachers were familiar with; breaking old habits can be difficult, but not impossible (Hancox et al., 2018). These findings could potentially be used to improve the design and content of future interventions and training programs. They can help to address the raised concerns and facilitate pre-service teachers to take up motivational interaction more effectively. The ultimate aim of adopting this new style is to improve teacher–student interaction in PE and thereby also students’ personal interest in PA.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the Finnish Social Science Data Archive (FSD): 3453 Liikettä toiselle asteelle: yksilöhaastattelut 2017–2018.

References

Aelterman N, Vansteenkiste M, Haerens L, Soenens B, Fontaine J, Reeve J (2019) Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: the merits of a circumplex approach. J Educ Psychol 111(3):497–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000293

Aelterman N, Vansteenkiste M, Keer H, Haerens L (2016) Changing teachers’ beliefs regarding autonomy support and structure: the role of experienced psychological need satisfaction in teacher training. Psychol Sport Exerc 23:64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.10.007

Aelterman N, Vansteenkiste M, Van Keer H, De Meyer J, Van den Berghe L, Haerens L (2013) Development and evaluation of a training on need-supportive teaching in physical education: qualitative and quantitative findings. Teach Teach Educ 29(1):64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.09.001

Aelterman N, Vansteenkiste M, Van den Berghe L, De Meyer J, Haerens L (2014) Fostering a need-supportive teaching style: intervention effects on physical education teachers’ beliefs and teaching behaviors. J Sport Exerc Psychol 36(6):595–609. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0229

Breckon J (2015) Motivational Interviewing, exercise & nutritional counselling. In: Anderson MB, Hanrahan SJ (ed) Doing exercise psychology. Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL, pp. 75–99

Cheon SH, Reeve J, Moon IS (2012) Experimentally based, longitudinally designed, teacher-focused intervention to help physical education teachers be more autonomy supportive toward their students. J Sport Exerc Psychol 34(3):365–96. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.34.3.365

de Roten Y, Zimmermann G, Ortega D, Despland JN (2013) Meta-analysis of the effects of MI training on clinicians’ behavior. J Subst Abuse Treat 45(2):155–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.02.006

Frost H, Campbell P, Maxwell M, O’Carroll RE, Dombrowski SU, Williams B, Cheyne H, Coles E, Pollock A (2018) Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0204890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204890

Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 62:107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Goggin K, Hawes SM, Duval ER, Spresser CD, Martínez DA, Lynam I, Catley DA (2010) Motivational interviewing course for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm 74:70. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj740470

Hall K, Staiger PK, Simpson A, Best D, Lubman DI (2016) After 30 years of dissemination, have we achieved sustained practice change in motivational interviewing? Addiction 111(7):1144–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13014

Hancox J, Quested E, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntoumani C (2018) Putting self-determination theory into practice: application of adaptive motivational principles in the exercise domain. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 10(1):75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1354059

Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis NL (2016) The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 86(2):360–407. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315585005

Hankonen N, Absetz P, Araujo-Soares V (2020) Changing activity behaviours in vocational school students: the stepwise development and optimised content of the ‘Let’s move it’ intervention. Health Psychol Behav Med 8(1):440–460

Hardcastle SJ, Fortier M, Blake N, Hagger MS (2017) Identifying content-based and relational techniques to change behaviour in motivational interviewing. Health Psychol Rev 11(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1190659

Hilton C, Poulter E (2008) Motivational interviewing and physical activity. 12sportEX health 19(Oct):10–12

Howard LM, Williams BA (2016) A Focused ethnography of baccalaureate nursing students who are using motivational interviewing. J Nurs Scholarsh 48(5):472–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12224

Krijgsman C, Mainhard T, van Tartwijk J, Borghouts L, Vansteenkiste M, Aelterman N, Haerens L (2019) Where to go and how to get there: goal clarification, process feedback and students’ need satisfaction and frustration from lesson to lesson. Learn Instr 61:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.12.005

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group (2012) Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 380(9838):219–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C (2009) Training in motivational interviewing: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 36(1):101–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005

Markland D, Ryan RM, Tobin VJ, Rollnick S (2005) Motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 24:811–831. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2005.24.6.811

Matosic D, Ntoumanis N, Quested E (2016) Antecedents of need supportive and controlling interpersonal styles from a self-determination theory perspective: a review and implications for sport psychology research. In: Raab M et al (eds) Sport and exercise psychology research. Academic Press, pp. 145–180.

McQuillin SD, Lyons MD (2016) Brief instrumental school-based mentoring for middle school students: theory and impact. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot 9(2):73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2016.1148620

Meng HY, Whipp P, Dimmock J, Jackson B (2013) The effects of choice on autonomous motivation, perceived autonomy support, and physical activity levels in high school physical education. J Teach Phys Educ 32(2):131–148. https://doi.org/10.1123/jtpe.32.2.131

Miller WR, Mount KA (2001) A small study of training in motivational interviewing: does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behav Cogn Psychother 29(4):457–471. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465801004064

Miller WR, Rollnick S (2013) Motivational interviewing: helping people change, 3rd edn. Guilford Press.

Mouratidis A, Vansteenkiste M, Michou A, Lens W (2013) Perceived structure and achievement goals as predictors of students’ self-regulated learning and affect and the mediating role of competence need satisfaction. Learn Individ Differ 23:179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.09.001

Ng JYY, Ntoumanis N, Thøgersen-Ntouman C, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Duda JL, Williams GC (2012) Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci 7(4):325–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612447309

Patrick H, Williams GC (2012) Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-18

Pignataro R, Huddleston J (2015) The use of motivational interviewing in physical therapy education and practice: empowering patients through effective self‐management. J Phys Ther Educ 29:62–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001416-201529020-00009

Polkinghorne DE (1988) Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. SUNY Press.

Potthoff S, Kwasnicka D, Avery L, Finch T, Gardner B, Hankonen N, Johnston D (2022) Changing healthcare professionals’ non-reflective processes to improve the quality of care. Soc Sci Med 298:114840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114840

Reeve J (1998) Autonomy support as an interpersonal motivating style: is it teachable. Contemp Educ Psychol 23(3):312–330. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1997.0975

Reeve J, Halusic M (2009) How K-12 teachers can put self-determination theory principles into practice. School Field 7(2):145–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104319

Reich C, Howard SK, Berman J (2015) A motivational interviewing intervention for the classroom. Teach Psychol 42(4):339–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628315603250

Rhodes R, Grant S, De Bruijn G (2020) Planning and implementation intention interventions. In: Hagger M. et al (eds) The handbook of behavior change. Cambridge handbooks in psychology. Cambridge University Press, pp. 572–585.

Rollnick S, Kaplan SG, Rutschman R (2016) Motivational interviewing in schools: conversations to improve behavior and learning. Guilford Press, New York, NY

Rollnick S, Miller WR (1995) What is Motivational Interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother 23(4):325–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246580001643X

Rosengren DB (2009) Building motivational interviewing skills: a practitioner workbook. Guilford Press.

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2020) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 61(101860). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis J (2017) Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res 217(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, Zweben A (2014) Sustaining motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of training studies. Addiction 109(8):1287–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12558

Sheldon LA (2010) Using motivational interviewing to help your students. Thought Action Fall, 153–158.

Shepard S, Herman KC, Reinke WM, Frey A (2014) Motivational interviewing in schools: strategies for engaging parents, teachers, and students. Springer, New York, NY

Su YL, Reeve J (2011) A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of intervention programs designed to support autonomy. Educ Psychol Rev 23(1):159–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9142-7

Söderlund LL, Nilsen P, Kristensson M (2008) Learning motivational interviewing: exploring primary health care nurses’ training and counselling experiences. Health Educ J 67(2):102–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896908089389

Teixeira PJ, Carraça EV, Markland DA, Silva MN, Ryan RM (2012) Exercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys 9(78). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-78

Teixeira PJ, Marques MM, Silva MN, Brunet J, Duda JL, Haerens L, Hagger MS (2020) A classification of motivation and behavior change techniques used in self-determination theory-based interventions in health contexts. Motiv Sci 6:4. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000172

Van Doren N, De Cocker K, De Clerck T, Vangilbergen A, Vanderlinde R, Haerens L (2021) The relation between physical education teachers’ (de-)motivating style, students’ motivation, and students’ physical activity: a multilevel approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(14):7457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147457

Vansteenkiste M, Sheldon KM (2006) There’s nothing more practical than a good theory: integrating motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. Br J Clin Psychol 45(1):63–82. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X34192

Velasquez MM, Stephens NS, Ingersoll K (2006) Motivational interviewing in groups. J Groups Addict Recover 1(1):27–50. https://doi.org/10.1300/J384v01n01_03

Wallace TL, Sung HC (2017) Student perceptions of autonomy-supportive instructional interactions in the middle grades. J Exp Educ 85(3):425–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2016.1182885

Wells H, Jones A (2018) Learning to change: the rationale for the use of motivational interviewing in higher education. Innov Educ Teach Int 55(1):111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1198714

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants. We would also like to thank MSc Elisa Kaaja and MSc Katariina Köykkä for their contributions to the planning of the study and data collection, and the entire network of stakeholders and research collaborators of various help along the way. This work was supported by a grant from the Academy of Finland [304114] to Principal Investigator Nelli Hankonen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors had substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. The interviews and the analysis were conducted by the first author. All authors participated in the interpretation of data. All authors drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed by the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in the Humanities and Social and Behavioural Sciences. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Renko, E., Koski-Jännes, A., Absetz, P. et al. A qualitative study of pre-service teachers’ experienced benefits and concerns of using motivational interaction in practice after a training course. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 458 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01484-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01484-y

- Springer Nature Limited