Abstract

Peer reviewers serve a vital role in assessing the value of published scholarship and improving the quality of submitted manuscripts. To provide more appropriate and systematic support to peer reviewers, especially those new to the role, this study documents the feedback practices and experiences of two award-winning peer reviewers in the field of education. Adopting a conceptual framework of feedback literacy and an autoethnographic-ecological lens, findings shed light on how the two authors design opportunities for feedback uptake, navigate responsibilities, reflect on their feedback experiences, and understand journal standards. Informed by ecological systems theory, the reflective narratives reveal how they unravel the five layers of contextual influences on their feedback practices as peer reviewers (micro, meso, exo, macro, chrono). Implications related to peer reviewer support are discussed and future research directions are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The peer-review process is the longstanding method by which research quality is assured. On the one hand, it aims to assess the quality of a manuscript, with the desired outcome being (in theory if not always in practice) that only research that has been conducted according to methodological and ethical principles be published in reputable journals and other dissemination outlets (Starck, 2017). On the other hand, it is seen as an opportunity to improve the quality of manuscripts, as peers identify errors and areas of weakness, and offer suggestions for improvement (Kelly et al., 2014). Whether or not peer review is actually successful in these areas is open to considerable debate, but in any case it is the “critical juncture where scientific work is accepted for publication or rejected” (Heesen and Bright, 2020, p. 2). In contemporary academia, where higher education systems across the world are contending with decreasing levels of public funding, there is increasing pressure on researchers to be ‘productive’, which is largely measured by the number of papers published, and of funding grants awarded (Kandiko, 2010), both of which involve peer review.

Researchers are generally invited to review manuscripts once they have established themselves in their disciplinary field through publication of their own research. This means that for early career researchers (ECRs), their first exposure to the peer-review process is generally as an author. These early experiences influence the ways ECRs themselves conduct peer review. However, negative experiences can have a profound and lasting impact on researchers’ professional identity. This appears to be particularly true when feedback is perceived to be unfair, with feedback tone largely shaping author experience (Horn, 2016). In most fields, reviewers remain anonymous to ensure freedom to give honest and critical feedback, although there are concerns that a lack of accountability can result in ‘bad’ and ‘rude’ reviews (Mavrogenis et al., 2020). Such reviews can negatively impact all researchers, but disproportionately impact underrepresented researchers (Silbiger and Stubler, 2019). Regardless of career phase, no one is served well by unprofessional reviews, which contribute to the ongoing problem of bullying and toxicity prevalent in academia, with serious implications on the health and well-being of researchers (Keashly and Neuman, 2010).

Because of its position as the central process through which research is vetted and refined, peer review should play a similarly central role in researcher training, although it rarely features. In surveying almost 3000 researchers, Warne (2016) found that support for reviewers was mostly received “in the form of journal guidelines or informally as advice from supervisors or colleagues” (p. 41), with very few engaging in formal training. Among more than 1600 reviewers of 41 nursing journals, only one third received any form of support (Freda et al., 2009), with participants across both of these studies calling for further training. In light of the lack of widespread formal training, most researchers learn ‘on the job’, and little is known about how researchers develop their knowledge and skills in providing effective assessment feedback to their peers. In this study, we undertake such an investigation, by drawing on our first-hand experiences. Through a collaborative and reflective process, we look to identify the forms and forces of our feedback literacy development, and seek to answer specifically the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the exhibited features of peer reviewer feedback literacy?

-

2.

What are the forces at work that affect the development of feedback literacy?

Literature review

Conceptualisation of feedback literacy

The notion of feedback literacy originates from the research base of new literacy studies, which examines ‘literacies’ from a sociocultural perspective (Gee, 1999; Street, 1997). In the educational context, one of the most notable types of literacy is assessment literacy (Stiggins, 1999). Traditionally, assessment literacy is perceived as one of the indispensable qualities of a successful educator, which refers to the skills and knowledge for teachers “to deal with the new world of assessment” (Fulcher, 2012, p. 115). Following this line of teacher-oriented assessment literacy, recent attempts have been made to develop more subject-specific assessment literacy constructs (e.g., Levi and Inbar-Lourie, 2019). Given the rise of student-centred approaches and formative assessment in higher education, researchers began to make the case for students to be ‘assessment literate’; comprising of such knowledge and skills as understanding of assessment standards, the relationship between assessment and learning, peer assessment, and self-assessment skills (Price et al., 2012). Feedback literacy, as argued by Winstone and Carless (2019), is essentially a subset of assessment literacy because “part of learning through assessment is using feedback to calibrate evaluative judgement” (p. 24). The notion of feedback literacy was first extensively discussed by Sutton (2012) and more recently by Carless and Boud (2018). Focusing on students’ feedback literacy, Sutton (2012) conceptualised feedback literacy as a three-dimensional construct—an epistemological dimension (what do I know about feedback?), an ontological dimension (How capable am I to understand feedback?), and a practical dimension (How can I engage with feedback?). In close alignment with Sutton’s construct, the seminal conceptual paper by Carless and Boud (2018) further illustrated the four distinctive abilities of feedback literate students: the abilities to (1) understand the formative role of feedback, (2) make informed and accurate evaluative judgement against standards, (3) manage emotions especially in the face of critical and harsh feedback, and (4) take action based on feedback. Since the publication of Carless and Boud (2018), student and teacher feedback literacy has been in the limelight of assessment research in higher education (e.g., Chong 2021b; Carless and Winstone 2020). These conceptual contributions expand the notion of feedback literacy to consider not only the manifestations of various forms of effective student engagement with feedback but also the confluence of contexts and individual differences of students in developing students’ feedback literacy by drawing upon various theoretical perspectives (e.g., ecological systems theory; sociomaterial perspective) and disciplines (e.g., business and human resource management). Others address practicalities of feedback literacy; for example, how teachers and students can work in synergy to develop feedback literacy (Carless and Winstone, 2020) and ways to maximise student engagement with feedback at a curricular level (Malecka et al., 2020). In addition to conceptualisation, advancement of the notion of feedback literacy is evident in the recent proliferation of primary studies. The majority of these studies are conducted in the field of higher education, focusing mostly on student feedback literacy in classrooms (e.g., Molloy et al., 2019; Winstone et al., 2019) and in the workplace (Noble et al., 2020), with a handful focused on teacher feedback literacy (e.g., Xu and Carless 2016). Some studies focusing on student feedback literacy adopt a qualitative case study research design to delve into individual students’ experience of engaging with various forms of feedback. For example, Han and Xu (2019) analysed the profiles of feedback literacy of two Chinese undergraduate students. Findings uncovered students’ resistance to engagement with feedback, which relates to the misalignment between the cognitive, social, and affective components of individual students’ feedback literacy profiles. Others reported interventions designed to facilitate students’ uptake of feedback, focusing on their effectiveness and students’ perceptions. Specifically, affordances and constraints of educational technology such as electronic feedback portfolio (Chong, 2019; Winstone et al., 2019) are investigated. Of particular interest is a recent study by Noble et al. (2020), which looked into student feedback literacy in the workplace by probing into the perceptions of a group of Australian healthcare students towards a feedback literacy training programme conducted prior to their placement. There is, however, a dearth of primary research in other areas where elicitation, process, and enactment of feedback are vital; for instance, academics’ feedback literacy. In the ‘publish or perish’ culture of higher education, academics, especially ECRs, face immense pressure to publish in top-tiered journals in their fields and face the daunting peer-review process, while juggling other teaching and administrative responsibilities (Hollywood et al., 2019; Tynan and Garbett 2007). Taking up the role of authors and reviewers, researchers have to possess the capacity and disposition to engage meaningfully with feedback provided by peer reviewers and to provide constructive comments to authors. Similar to students, researchers have to learn how to manage their emotions in the face of critical feedback, to understand the formative values of feedback, and to make informed judgements about the quality of feedback (Gravett et al., 2019). At the same time, feedback literacy of academics also resembles that of teachers. When considering the kind of feedback given to authors, academics who serve as peer reviewers have to (1) design opportunities for feedback uptake, (2) maintain a professional and supportive relationship with authors, and (3) take into account the practical dimension of giving feedback (e.g., how to strike a balance between quality of feedback and time constraints due to multiple commitments) (Carless and Winstone 2020). To address the above, one of the aims of the present study is to expand the application of feedback literacy as a useful analytical lens to areas outside the classroom, that is, scholarly peer-review activities in academia, by presenting, analysing, and synthesising the personal experiences of the authors as successful peer reviewers for academic journals.

Conceptual framework

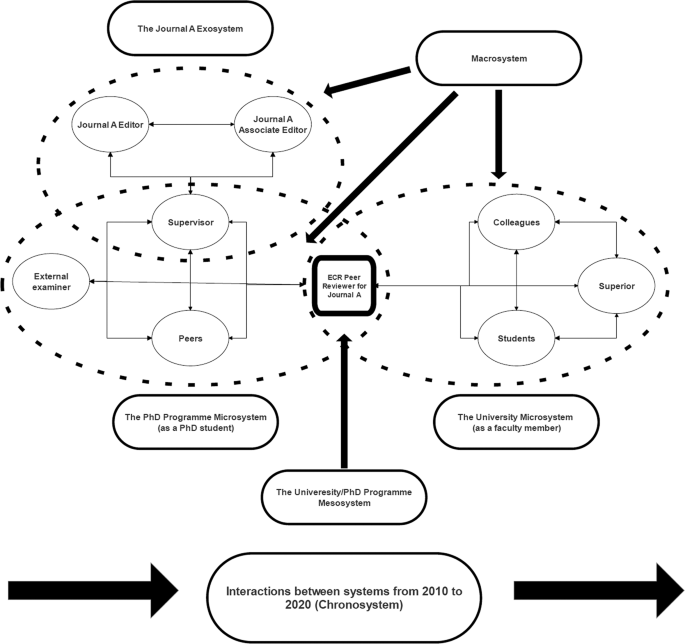

We adopt a feedback literacy of peer reviewers framework (Chong 2021a) as an analytical lens to analyse, systemise, and synthesise our own experiences and practices as scholarly peer reviewers (Fig. 1). This two-tier framework includes a dimension on the manifestation of feedback literacy, which categorises five features of feedback literacy of peer reviewers, informed by student and teacher feedback literacy frameworks by Carless and Boud (2018) and Carless and Winstone (2020). When engaging in scholarly peer review, reviewers are expected to be able to provide constructive and formative feedback, which authors can act on in their revisions (engineer feedback uptake). Besides, peer reviewers who are usually full-time researchers or academics lead hectic professional lives; thus, when writing reviewers’ reports, it is important for them to consider practically and realistically the time they can invest and how their various degrees of commitment may have an impact on the feedback they provide (navigate responsibilities). Furthermore, peer reviewers should consider the emotional and relational influences their feedback exert on the authors. It is crucial for feedback to be not only informative but also supportive and professional (Chong, 2018) (maintain relationships). Equally important, it is imperative for peer reviewers to critically reflect on their own experience in the scholarly peer-review process, including their experience of receiving and giving feedback to academic peers, as well as the ways authors and editors respond to their feedback (reflect on feedback experience). Lastly, acting as gatekeepers of journals to assess the quality of manuscripts, peer reviewers have to demonstrate an accurate understanding of the journals’ aims, remit, guidelines and standards, and reflect those in their written assessments of submitted manuscripts (understand standards). Situated in the context of scholarly peer review, this collaborative autoethnographic study conceptualises feedback literacy not only as a set of abilities but also orientations (London and Smither, 2002; Steelman and Wolfeld, 2016), which refers to academics’ tendency, beliefs, and habits in relation to engaging with feedback (London and Smither, 2002). According to Cheung (2000), orientations are influenced by a plethora of factors, namely experiences, cultures, and politics. It is important to understand feedback literacy as orientations because it takes into account that feedback is a convoluted process and is influenced by a plethora of contextual and personal factors. Informed by ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Neal and Neal, 2013) and synthesising existing feedback literacy models (Carless and Boud, 2018; Carless and Winstone, 2020; Chong, 2021a, 2021b), we consider feedback literacy as a malleable, situated, and emergent construct, which is influenced by the interplay of various networked layers of ecological systems (Neal and Neal, 2013) (Fig. 1). Also important is that conceptualising feedback literacy as orientations avoids dichotomisation (feedback literate vs. feedback illiterate), emphasises the developmental nature of feedback literacy, and better captures the multifaceted manifestations of feedback engagement.

Echoing recent conceptual papers on feedback literacy which emphasises the indispensable role of contexts (Chong 2021b; Boud and Dawson, 2021; Gravett et al., 2019), our conceptual framework includes an underlying dimension of networked ecological systems (micro, meso, exo, macro, and chrono), which portrays the contextual forces shaping our feedback orientations. Informed by the networked ecological system theory of Neal and Neal (2013), we postulate that there are five systems of contextual influence, which affect the feedback experience and development of feedback literacy of peer reviewers. The five ecological systems refer to ‘settings’, which is defined by Bronfenbrenner (1986) as “place[s] where people can readily engage in social interactions” (p. 22). Even though Bronfenbrenner’s (1986) somewhat dated definition of ‘place’ is limited to ‘physical space’, we believe that ‘places’ should be more broadly defined in the 21st century to encompass physical and virtual, recent and dated, closed and distanced locations where people engage; as for ‘interactions’, from a sociocultural perspective, we understand that ‘interactions’ can include not only social, but also cognitive and emotional exchanges (Vygotsky, 1978). Microsystem refers to a setting where people, including the focal individual, interact. Mesosystem, on the other hand, means the interactions between people from different settings and the influence they exert on the focal individual. An exosystem, similar to a microsystem, is understood as a single setting but this setting excludes the focal individual but it is likely that participants in this setting would interact with the focal individual. The remaining two systems, macrosystem and chronosystem, refer not only to ‘settings’ but ‘forces that shape the patterns of social interactions that define settings’ (Neal and Neal, 2013, p. 729). Macrosystem is “the set of social patterns that govern the formation and dissolution of… interactions… and thus the relationship among ecological systems” (ibid). Some examples of macrosystems given by Neal and Neal (2013) include political and cultural systems. Finally, chronosystem is “the observation that patterns of social interactions between individuals change over time, and that such changes impact on the focal individual” (ibid, p. 729). Figure 2 illustrates this networked ecological systems theory using a hypothetical example of an early career researcher who is involved in scholarly peer review for Journal A; at the same time, they are completing a PhD and are working as a faculty member at a university.

Methods

From the reviewed literature on the construct of feedback literacy, the investigation of feedback literacy as a personal, situated, and unfolding process is best done through an autoethnographic lens, which underscores critical self-reflection. Autoethnography refers to “an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno)” (Ellis et al., 2011, p. 273). Autoethnography stems from research in the field of anthropology and is later introduced to the fields of education by Ellis and Bochner (1996). In higher education research, autoethnographic studies are conducted to illuminate on topics related to identity and teaching practices (e.g., Abedi Asante and Abubakari, 2020; Hains-Wesson and Young 2016; Kumar, 2020). In this article, a collaborative approach to autoethnography is adopted. Based on Chang et al. (2013), Lapadat (2017) defines collaborative autoethnography (CAE) as follows:

… an autobiographic qualitative research method that combines the autobiographic study of self with ethnographic analysis of the sociocultural milieu within which the researchers are situated, and in which the collaborating researchers interact dialogically to analyse and interpret the collection of autobiographic data. (p. 598)

CAE is not only a product but a worldview and process (Wall, 2006). CAE is a discrete view about the world and research, which straddles between paradigmatic boundaries of scientific and literary studies. Similar to traditional scientific research, CAE advocates systematicity in the research process and consideration is given to such crucial research issues as reliability, validity, generalisability, and ethics (Lapadat, 2017). In closer alignment with studies on humanities and literature, the goal of CAE is not to uncover irrefutable universal truths and generate theories; instead, researchers of CAE are interested in co-constructing and analysing their own personal narratives or ‘stories’ to enrich and/or challenge mainstream beliefs and ideas, embracing diverse rather than canonical ways of behaviour, experience, and thinking (Ellis et al., 2011). Regarding the role of researchers, CAE researchers openly acknowledge the influence (and also vulnerability) of researchers throughout the research process and interpret this juxtaposition of identities between researchers and participants of research as conducive to offering an insider’s perspective to illustrate sociocultural phenomena (Sughrua, 2019). For our CAE on the scholarly peer-review experiences of two ECRs, the purpose is to reconstruct, analyse, and publicise our lived experience as peer reviewers and how multiple forces (i.e., ecological systems) interact to shape our identity, experience, and feedback practice. As a research process, CAE is a collaborative and dynamic reflective journey towards self-discovery, resulting in narratives, which connect with and add to the existing literature base in a personalised manner (Ellis et al., 2011). The collaborators should go beyond personal reflection to engage in dialogues to identify similarities and differences in experiences to throw new light on sociocultural phenomena (Merga et al., 2018). The iterative process of self- and collective reflections takes place when CAE researchers write about their own “remembered moments perceived to have significantly impacted the trajectory of a person’s life” and read each other’s stories (Ellis et al., 2011, p. 275). These ‘moments’ or vignettes are usually written retrospectively, selectively, and systematically to shed light on facets of personal experience (Hughes et al., 2012). In addition to personal stories, some autoethnographies and CAEs utilise multiple data sources (e.g., reflective essays, diaries, photographs, interviews with co-researchers) and various ways of expressions (e.g., metaphors) to achieve some sort of triangulation and to present evidence in a ‘systematic’ yet evocative manner (Kumar, 2020). One could easily notice that overarching methodological principles are discussed in lieu of a set of rigid and linear steps because the process of reconstructing experience through storytelling can be messy and emergent, and certain degree of flexibility is necessary. However, autoethnographic studies, like other primary studies, address core research issues including reliability (reader’s judgement of the credibility of the narrator), validity (reader’s judgement that the narratives are believable), and generalisability (resemblance between the reader’s experience and the narrative, or enlightenment of the reader regarding unfamiliar cultural practices) (Ellis et al., 2011). Ethical issues also need to be considered. For example, authors are expected to be honest in reporting their experiences; to protect the privacy of the people who ‘participated’ in our stories, pseudonyms need to be used (Wilkinson, 2019). For the current study, we follow the suggested CAE process outlined by Chang et al. (2013), which includes four stages: deciding on topic and method, collecting materials, making meaning, and writing. When deciding on the topic, we decided to focus on our experience as scholarly peer reviewers because doing peer review and having our work reviewed are an indispensable part of our academic lives. The next is to collect relevant autoethnographic materials. In this study, we follow Kumar (2020) to focus on multiple data sources: (1) reflective essays which were written separately through ‘recalling’, which is referred to by Chang et al. (2013) as ‘a free-spirited way of bringing out memories about critical events, people, place, behaviours, talks, thoughts, perspectives, opinions, and emotions pertaining to the research topic’ (p. 113), and (2) discussion meetings. In our reflective essays, we included written records of reflection and excerpts of feedback in our peer-review reports. Following material collection is meaning making. CAE, as opposed to autoethnography, emphasises the importance of engaging in dialogues with collaborators and through this process we identify similarities and differences in our experiences (Sughrua, 2019). To do so, we exchanged our reflective essays; we read each other’s reflections and added questions or comments on the margins. Then, we met online twice to share our experiences and exchange views regarding the two reflective essays we wrote. Both meetings lasted for approximately 90 min, were audio-recorded and transcribed. After each meeting, we coded our stories and experiences with reference to the two dimensions of the ecological framework of feedback literacy (Fig. 1). With regards to coding our data, we followed the model of Miles and Huberman (1994), which comprises four stages: data reduction (abstracting data), data display (visualising data in tabular form), conclusion-drawing, and verification. The coding and writing processes were done collaboratively on Google Docs and care was taken to address the aforesaid ethical (e.g., honesty, privacy) and methodological issues (e.g., validity, reliability, generalisability). As a CAE study, the participants are the researchers themselves, that is, the two authors of this paper. We acknowledge that research data are collected from human subjects (from the two authors), such data are collected in accordance with the standards and guidelines of the School Research Ethics Committee at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work, Queen’s University Belfast (Ref: 005_2021). Despite our different experiences in our unique training and employment contexts, we share some common characteristics, both being ECRs (<5 years post-PhD), working in the field of education, active in the scholarly publication process as both authors and peer reviewers. Importantly for this study, we were both recipients of Reviewer of the Year Award 2019 awarded jointly by the journal, Higher Education Research & Development and the publisher, Taylor & Francis. This award in recognition of the quality of our reviewing efforts, as determined by the editorial board of a prestigious higher education journal, provided a strong impetus for this study, providing an opportunity to reflect on our own experiences and practices. The extent of our peer-review activities during our early career leading up to the time of data collection is summarised in Table 1.

Findings and discussion

Analysis of the four individual essays (E1 and E2 for each participant) and transcripts of the two subsequent discussions (D1 and D2) resulted in the identification of multiple descriptive codes and in turn a number of overarching themes (Supplementary Appendix 1). Our reporting of these themes is guided by our conceptual framework, where we first focus on the five manifestations of feedback literacy to highlight the experiences that contribute to our growth as effective and confident peer reviewers. Then, we report on the five ecological systems to unravel how each contextual layer develops our feedback literacy as peer reviewers. (Note that the discussion of the chronosystem has been necessarily incorporated into each of the four others dimensions: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem in order to demonstrate temporal changes). In particular, similarities and differences will be underscored, and connections with manifested feedback beliefs and behaviours will be made. We include quotes from both Author 1 (A1) and Author 2 (A2), in order to illustrate our findings, and to show the richness and depth of the data collected (Corden and Sainsbury, 2006). Transcribed quotes may be lightly edited while retaining meaning, for example through the removal of fillers and repetitions, which is generally accepted practice to ensure readability (ibid).

Manifestations of feedback literacy

Engineering feedback uptake

The two authors have a strong sense of the purpose of peer review as promoting not only research quality, but the growth of researchers. One way that we engineer author uptake is to ensure that feedback is ‘clear’ (A2,E1), ‘explicit’ (A2,E1), ‘specific’ (A1,E1), and importantly ‘actionable… to ensure that authors can act on this feedback so that their manuscripts can be improved and ultimately accepted for publication’ (A1,E1). In less than favourable author outcomes, we ensure that there is reference to the role of the feedback in promoting the development of the manuscript, which A1 refers to as ‘promotion of a growth mindset’ (A1,E1). For example, after requesting a second round of major revisions, A2 ‘acknowledged the frustration that the author might have felt on getting further revisions by noting how much improvement was made to the paper, but also making clear the justification for sending it off for more work’ (A2,E1). We both note that we tend to write longer reviews when a rejection is the recommended outcome, as our ultimate goal is to aid in the development of a manuscript.

Rejections doesn’t mean a paper is beyond repair. It can still be fixed and improved; a rejection simply means that the fix may be too extensive even for multiple review cycles. It is crucial to let the authors whose manuscripts are rejected know that they can still act on the feedback to improve their work; they should not give up on their own work. I think this message is especially important to first-time authors or early career researchers. (A1,E1)

In promoting a growth mindset and in providing actionable feedback, we hope to ‘show the authors that I’m not targeting them, but their work’ (A1,D1). We particularly draw on our own experiences as ECRs, with first-hand understanding that ‘everyone takes it personally when they get rejected. Yeah. Moreover, it is hard to separate (yourself from the paper)’ (A2,D1).

Navigating responsibilities

As with most academics, the two authors have multiple pressures on their time, and there ‘isn’t much formal recognition or reward’ (A1,E1) and ‘little extrinsic incentive for me to review’ (A2,E1). Nevertheless we both view our roles as peer reviewers as ‘an important part of the process’ (A2,E1), ‘a modest way for me to give back to the academic community’ (A1,E1). Through peer review we have built a sense of ‘identity as an academic’ (A1,D1), through ‘being a member of the academic community’ (A2,D1). While A1 commits to ‘review as many papers as possible’ (A1,E1) and A2 will usually accept offers to review, there are still limits on our time and therefore we consider the topic and methods employed when deciding whether or not to accept an invitation, as well as the journal itself, as we feel we can review more efficiently for journals with which we are more familiar. A1 and A2 have different processes for conducting their review that are most efficient for their own situations. For A1, the process begins with reading the whole manuscript in one go, adding notes to the pdf document along the way, which he then reviews, and makes a tentative decision, including ‘a few reasons why I have come to this decision’ (A1,E1). After waiting at least one day, he reviews all of the notes and begins writing the report, which is divided into the sections of the paper. He notes it ‘usually takes me 30–45 min to write a report. I then proofread this report and submit it to the system. So it usually takes me no more than three hours to complete a review’ (A1,E1). For A2, the process for reviewing and structuring the report is quite different, with a need to ‘just find small but regular opportunities to work on the review’ (A2,E1). As was the case during her Ph.D, which involved juggling research and raising two babies, ‘I’ve trained myself to be able to do things in bits’ (A2,D1). So A2 also begins by reading the paper once through, although generally without making initial comments. The next phase involves going through the paper at various points in time whenever possible, and at the same time building up the report, making the report structurally slightly different to that of A1.

What my reviews look like are bullet points, basically. And they’re not really in a particular order. They generally… follow the flow (of the paper). But I mean, I might think of something, looking at the methods and realise, hey, you haven’t defined this concept in the literature review so I’ll just add you haven’t done this. And so I will usually preface (the review)… Here’s a list of suggestions. Some of them are minor, some of them are serious, but they’re in no particular order. (A1,D1)

As such, both reviewers engage in personalised strategies to make more effective use of their time. Both A1 and A2 give explicit but not exhaustive examples of an area of concern, and they also pose questions for the author to consider, in both cases placing the onus back on the author to take action. As A1 notes, ‘I’m not going to do a summary of that reference for you. I’m just going to include that there. If you’d like you can check it out’ (A1,D1). For A2, a lack of adequate reporting of the methods employed in a study makes it difficult to proceed, and in such cases will not invest further time, sending it back to the editor, because ‘I can’t even comment on the findings… I can’t go on. I’m not gonna waste my time’ (A2,D1). In cases where the authors may be ‘on the fence’ about a particular review, they will use the confidential comments to the editor to help work through difficult cases as ‘they are obviously very experienced reviewers’ (A1,D1). Delegating tasks to the expertise of the editorial teams when appropriate also ensures time is used more prudently.

Maintaining relationships

Except in a few cases where A2 has reviewed for journals with a single-blind model, the vast majority of the reviews that we have completed have been double-blind. This means that we are unaware of the identity of the author/s, and we are unknown to them. However, ‘even with blind-reviews I tend to think of it as a conversation with a person’ (A2,E1). A1 talks about the need to have respect for the author and their expertise and effort ‘regardless of the quality of the submission (which can be in some cases subjective)’ (A1,E1). A2 writes similarly about the ‘privilege’ and ‘responsibility’ of being able to review manuscripts that authors ‘have put so much time and energy into possibly over an extended period’ (A2,E1). In this way it is possible to develop a sort of relationship with an author even without knowing their identity. In trying to articulate the nature of that relationship (which we struggle to do so definitively), we note that it is more than just a reviewer, and A2 reflected on a recent review, which went through a number of rounds of resubmission where ‘it felt like we were developing a relationship, more like a mentor than a reviewer’ (A2,E1).

I consider this role as a peer reviewer more than giving helpful and actionable feedback; I would like to be a supporter and critical friend to the authors, even though in most cases I don’t even know who they are or what career stage they are at (A1,E1).

In any case, as A1 notes, ‘we don’t even need to know who that person is because we know that people like encouragement’ (A1,D1), and we are very conscious of the emotional impact that feedback can have on authors, and the inherent power imbalance in the relationship. For this reason, A1 is ‘cautious about the way I write so that I don’t accidentally make the authors the target of my feedback’. As A2 notes ‘I don’t want authors feeling depressed after reading a review’ (A2,E1). While we note that we try to deliver our feedback with ‘respect’ (A1,E1; A1,E2; A2,D1) ‘empathy’ (A1,E1), and ‘kindness’ (A2,D1), we both noted that we do not ‘sugar coat’ our feedback and A1 describes himself as ‘harsh’ and ‘critical’ (A1,E1) while A2 describes herself as ‘pretty direct’ (A2,E1). In our discussion, we tried to delve into this seeming contradiction:… the encouragement, hopefully is to the researcher, but the directness it should be, I hope, is related directly to whatever it is, the methods or the reporting or the scope of the literature review. It’s something specific about the manuscript itself. And I know myself, being an ECR and being reviewed, that it’s hard to separate yourself from your work… And I want to make it really explicit. If it’s critical, it’s not about the person. It’s about the work, you know, the weakness of the work, but not the person. (A2,D1)

A1 explains that at times his initial report may be highly critical, and at times he will ‘sit back and rethink… With empathy, I will write feedback, which is more constructive’ (A1,E1). However, he adds that ‘I will never try to overrate a piece or sugar-coat my comments just to sound “friendly”’ (A1,E1), with the ultimate goal being to uphold academic rigour. Thus, honesty is seen as the best strategy to maintain a strong, professional relationship with reviewers. Another strategy employed by A2 is showing explicit commitment to the review process. One way this is communicated is by prefacing a review with a summary of the paper, not only ‘to confirm with the author that I am interpreting the findings in the way that they intended, but also importantly to show that I have engaged with the paper’ (A2,E1). Further, if the recommendation is for a further round of review, she will state directly to the authors ‘that I would be happy to review a revised manuscript’ (A2,E1).

Reflecting on feedback experience

As ECRs we have engaged in the scholarly publishing process initially as authors, subsequently as reviewers, and most recently as Associate Editors. Insights gained in each of these roles have influenced our feedback practices, and have interacted to ‘develop a more holistic understanding of the whole review process’ (A1,E1).

We reflect on our experiences as authors beginning in our doctoral candidatures, with reviews that ranged from ‘the most helpful to the most cynical’ (A1,E1). A2 reflected on two particular experiences both of which resulted in rejection, one being ‘snarky’ and ‘unprofessional’ with ‘no substance’, the other providing ‘strong encouragement … the focus was clearly on the paper and not me personally’ (A2,E1). It was this experience that showed the divergence between the tone and content of review despite the same outcome, and as result A2 committed to being ‘ the amazing one’. A1 also drew from a negative experience noting that ‘I remember the least useful feedback as much as I do with the most constructive one’ (A1,E1). This was particularly the case when a reviewer made apparently politically-motivated judgements that A1 ‘felt very uncomfortable with’ and flagged with the editor (A1,E1). Through these experiences both authors wrote in their essays about the need to focus on the work and not on the individual, with an understanding that a review ‘can have a really serious impact’ (A2,D1) on an author.

It is important to note that neither authors have been involved in any formal or informal training on how to conduct peer review, although A1 expresses appreciation of the regular practice of one journal for which he reviews, where ‘the editor would write an email to the reviewers giving feedback on the feedback we have given’ (A1,E1). For A2, an important source of learning is in comparing her reviews with that of others who have reviewed the same manuscript, the norm for some journals being to send all reports to all reviewers along with the final decision.

I’m always interested to see how [my] review compares with others. Have I given the same recommendation? Have I identified the same areas of weakness? Have I formatted my review in the same way? How does the tone of delivery differ? I generally find that I give a similar if not the same response to other reviews, and I’m happy to see that I often pick up the same issues with methodology. (A2,E1)

For A2 there is comfort in seeing reviews that are similar to others, although we both draw on experiences where our recommendation diverged from others, with a source of assurance being the ultimate decision of the editor.

So it’s like, I don’t think it can be published and that [other] reviewer thinks it’s excellent. So usually, what the editor would do in this instance is invite the third one. Right, yeah. But then this editor told me… that they decided to go with my decision to reject because they find that my comments are more convincing. (A1,D1)

A2 also was surprised to read another report of the same manuscript she reviewed, that raised similar concerns and gave the same recommendation for major revisions, but noted the ‘wording is soooo snarky. What need?’ (A2,E1). In one case that A1 detailed in our first discussion, significant but improbable changes made to the methodology section of a resubmitted paper caused him to question the honesty of the reporting, making him ‘uncomfortable’ and as a result reported his concerns to the editor. In this case the review took some time to craft, trying to balance the ‘fine line between catering for the emotion [of the author], right, and upholding the academic standards’ (A1,D1). While he conceded initially his report was ‘kind of too harsh… later I think I rephrased it a little bit, I kind of softened (it)’.

While the role of Associate Editor is very new to A2 and thus was yet unable to comment, for A1 the ‘opportunity to read various kinds of comments given by reviewers’ (A1,E1) is viewed favourably. This includes not only how reviewers structure their feedback, but also how they use the confidential comments to the editors to express their thoughts more openly, providing important insights into the process that are largely hidden.

Understanding standards

While our reviewing practices are informed more broadly ‘according to more general academic standards of the study itself, and the clarity and fullness of the reporting’ (A2,E1), we look in the first instance to advice and guidelines from journals to develop an understanding of journal-specific standards, although A2 notes that a lack of review guidelines for one of the earliest journals she reviewed led her to ‘searching Google for standard criteria’ (A2,E1). However, our development in this area seems to come from developing a familiarity with a journal, particularly through engagement with the journal as an author.

In addition to reading the scope and instructions for authors to obtain such basic information as readership, length of submissions, citation style, the best way for me to understand the requirements and preferences of the journals is my own experience as an author. I review for journals which I have published in and for those which I have not. I always find it easier to make a judgement about whether the manuscripts I review meet the journal’s standards if I have published there before. (A1,E1)

Indeed, it seems that journal familiarity is connected closely to our confidence in reviewing, and while both authors ‘review for journals which I have published in and for those which I have not’ (A1,E1), A2 states that she is reluctant to ‘readily accept an offer to review for a journal that I’m not familiar with’, and A1 takes extra time to ‘do more preparatory work before I begin reading the manuscript and writing the review’ when reviewing for an unfamiliar journal.

Ecological systems

Microsystem

Three microsystems exert influence on A1’s and A2’s development of feedback literacy: university, journal community, and Twitter.

In regards to the university, we are full-time academics in research-intensive universities in the UK and Japan where expectations for academics include publishing research in high-impact journals ‘which is vital to promotion’ (A1,E2). It is especially true in A2’s context where the national higher education agenda is to increase world rankings of universities. Thus, ‘there is little value placed on peer review, as it is not directly related to the broader agenda’ (A2,E2). When considering his recent relocation to the UK together with the current pandemic, A1 navigated his responsibilities within the university context and decided to allocate more time to his university-related responsibilities, especially providing learning and pastoral support to his students, who are mostly international students. Besides, A2 observed that there is a dearth of institution-wide support on conducting peer review although ‘there are a lot of training opportunities related to how to write academic papers in English, how to present at international conferences, how to write grant applications’, etc. (A2,E2). As a result, she ‘struggled for a couple of years’ because of the lack of institutional support for her development as a peer reviewer’ (A2,D2); but this helplessness also motivated her to seek her own ways to learn how to give feedback, such as ‘seeing through glimpses of other reviews, how others approach it, in terms of length, structure, tone, foci etc.’ (A2,E2). A1 shares the same view that no training is available at his institution to support his development as a peer reviewer. However, his postgraduate supervision experiences enabled him to reflect on how his feedback can benefit researchers. In our second online discussion, A1 shared that he held individual advising sessions with some postgraduate students, which made him realise that it is important for feedback to serve the function to inspire rather than to ‘give them right answers’ (A1,D2).

Because of the lack of formal training provided by universities, both authors searched for other professional communities to help us develop our expertise in giving feedback as peer reviewers, with journal communities being the next microsystem. We found that international journals provide valuable opportunities for us to understand more about the whole peer-review process, in particular the role of feedback. For A1, the training which he received from the editor-in-chief when he took up the associate editorship of a language education journal two years ago was particularly useful. A1 benefited greatly from meetings with the editor who walked him through every stage in the review process and provided ‘hands-on experience on how to handle delicate scenarios’ (A1,E2). Since then, A1 has had plenty of opportunities to oversee various stages of peer review and read a large number of reviewers’ reports which helped him gain ‘a holistic understanding of the peer-review process’ (A1,E2) and gradually made him become more cognizant of how he wants to give feedback. Although there was no explicit instruction on the technical aspect of giving feedback, A1 found that being an associate editor has developed his ‘consciousness’ and ‘awareness’ of giving feedback as a peer reviewer (A1,D2). Further, he felt that his editorial experiences provided him the awareness to constantly refine and improve his ways of giving feedback, especially ways to make his feedback ‘more structured, evidence-based, and objective’ (A1,E2). Despite not reflecting from the perspective of an editor, A2 recalled her experience as an author who received in-depth and constructive feedback from a reviewer, which really impacted the way she viewed the whole review process. She understood from this experience that even though the paper under review may not be particularly strong, peer reviewers should always aim to provide formative feedback which helps the authors to improve their work. These positive experiences of the two authors are impactful on the ways they give feedback as peer reviewers. In addition, close engagement with a specific journal has helped A2 to develop a sense of belonging, making it ‘much more than a journal, but also a way to become part of an academic community’ (A2,E2). With such a sense of belonging, it is more likely for her to be ‘pulled towards that journal than others’ when she can only review a limited number of manuscripts (A2,D2).

Another professional community in which we are both involved is Twitter. We regard Twitter as a platform for self-learning, reflection, and inspiration. We perceive Twitter as a space where we get to learn from others’ peer-review experiences and disciplinary practices. For example, A1 found the tweets on peer-review informative ‘because they are written by different stakeholders in the process—the authors, editors, reviewers’ and offer ‘different perspectives and sometimes different versions of the same story’ (A1,E2). A2 recalled a tweet she came across about the ‘infamous Reviewer 2’ and how she learned to not make the same mistakes (A2,D2). Reading other people’s experiences helps us reconsider our own feedback practices and, more broadly, the whole peer-review system because we ‘get a glimpse of the do’s and don’ts for peer reviewers’ (A1,E2).

Further to our three common microsystems, A2 also draws on a unique microsystem, that of her former profession as a teacher, which shapes her feedback practices in three ways. First, in her four years of teacher training, a lot of emphasis was placed on assessment and feedback such as ‘error correction’; this understanding related to giving feedback to students and was solidified through ‘learning on the job’ (A2,D2). Second, A2 acknowledges that as a teacher, she has a passion to ‘guide others in their knowledge and skill development… and continue this in our review practices’ (A2,E2). Finally, her teaching experience prepared her to consider the authors’ emotional responses in her peer-review feedback practices, constantly ‘thinking there’s a person there who’s going to be shattered getting a rejection’ (A2,D2).

Mesosystem

Mesosystem considers the confluence of our interactions in various microsystems. Particularly, we experienced a lack of support from our institutions, which pushed us to seek alternative paths to acquire the art of giving feedback. This has made us realise the importance of self-learning in developing feedback literacy as peer reviewers, especially in how to develop constructive and actionable feedback. Both authors self-learn how to give feedback by reading others’ feedback. A1 felt ‘fortunate to be involved in journal editing and Twitter’ because he gets ‘a glimpse of how other peer reviewers give feedback to authors’ (A1,E2). A2, on the other hand, learned through her correspondences with a journal editor who made her stop ‘looking for every word’ and move away from ‘over proofreading and over editing’ (A2,D2).

Focusing on the chronosystem, it is noticed that both authors adjusted how they give feedback over time because of the aggregated influence of their microsystems. What stands out is that they have become more strategic in giving feedback. One way this is achieved is through focusing their comments on the arguments of the manuscripts instead of burning the midnight oil with error-correcting.

Exosystem

Exosystem concerns the environment where the focal individuals do not have direct interactions with the people in it but have access to information about. In his case, A1’s understanding of advising techniques promoted by a self-access language learning centre is conducive to the cultivation of his feedback literacy. Although A1 is not a part of the language advising team, he has a working relationship with the director. A1 was especially impressed by the learner-centeredness of an advising process:

The primary duty of the language advisor is not to be confused with that of a language teacher. Language teachers may teach a lecture on a linguistic feature or correct errors on an essay, but language advisors focus on designing activities and engaging students in dialogues to help them reflect on their own learning needs… The advisors may also suggest useful resources to the students which cater to their needs. In short, language advisors work in partnership with the students to help them improve their language while language teachers are often perceived as more authoritative figures (A1, E2).

His understanding of advising has affected how A1 provides feedback as a peer reviewer in a number of ways. First, A1 places much more emphasis on humanising his feedback, for example, by considering ‘ways to work in partnership with the authors and making this “partnership mindset” explicit to the authors through writing’ (A1,E2). One way to operationalise this ‘partnership mindset’ in peer review is to ‘ask a lot of questions’ and provide ‘multiple suggestions’ for the authors to choose from (A1,E2). Furthermore, his knowledge of the difference between feedback as giving advice and feedback as instruction has led him to include feedback, which points authors to additional resources. Below is a feedback point A1 gave in one of his reviews:

The description of the data analysis process was very brief. While we are not aiming at validity and reliability in qualitative studies, it is important for qualitative researchers to describe in detail how the data collected were analysed (e.g. iterative coding, inductive/deductive coding, thematic analysis) in order to ascertain that the findings were credible and trustworthy. See Johnny Saldaña’s ‘The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers’.

Another exosystem that we have knowledge about is formal peer-review training courses provided by publishers. These online courses are usually run asynchronously. Even though we did not enrol in these courses, our interest in peer review has led us to skim the content of these courses. Both of us questioned the value of formal peer-review training in developing feedback literacy of peer reviewers. For example, A2 felt that opportunities to review are more important because they ‘put you in that position where you have responsibility and have to think critically about how you are going to respond’ (A2,D2). To A1, formal peer-review training mostly focuses on developing peer reviewers’ ‘understanding of the whole mechanism’ but not providing ‘training on how to give feedback… For example, do you always ask a question without giving the answers you know? What is a good suggestion?’ (A1,D2).

Macrosystem

The two authors have diverse sociocultural experiences because of their family backgrounds and work contexts. When reflecting on their sociocultural experiences, A1 focused on his upbringing in Hong Kong where both of his parents are school teachers and his professional experience as a language teacher in secondary and tertiary education in Hong Kong while A2 discussed her experience of working in academia in Japan as an anglophone.

Observing his parents’ interactions with their students in schools, A1 was immersed in an Asian educational discourse characterised by ‘mutual respect and all sorts of formality’ (A1,E2). After he finished university, A1 became a school teacher and then a university lecturer (equivalent to a teaching fellow in the UK), getting immersed continuously in the etiquette of educational discourse in Hong Kong. Because of this, A1 knows that being professional means to be ‘formal and objective’ and there is a constant expectation to ‘treat people with respect’ (A1,E2). At the same time, his parents are unlike typical Asian parents; they are ‘more open-minded’, which made him more willing to listen and ‘consider different perspectives’ (A1,D2). Additionally, social hierarchy also impacted his approach to giving feedback as a peer reviewer. A1 started his career as a school teacher and then a university lecturer in Hong Kong with no formal research training. After obtaining his BA and MA, it is not until recently that A1 obtained his PhD by Prior Publication. Perhaps because of his background as a frontline teacher, A1 did not regard himself as ‘a formally trained researcher’ and perceived himself as not ‘elite enough to give feedback to other researchers’ (A1,E2). Both his childhood and his self-perceived identity have led to the formation of two feedback strategies: asking questions and providing a structured report mimicking the sections in the manuscript. A1 frequently asks questions in his reports ‘in a bid to offset some of the responsibilities to the authors’ (A1,E2). A1 struggles to decide whether to address authors using second- or third-person pronouns. A1 consistently uses third-person pronouns in his feedback because he wants to sound ‘very formal’ (A1,D2). However, A1 shared that he has recently started using second-person pronouns to make his feedback more interactive.

A2, on the other hand, pondered upon her sociocultural experiences as a school teacher in Australia, her position as an anglophone in a Japanese university, and her status as first-generation high school graduate. Reflecting on her career as a school teacher, A2 shared that her students had high expectations on her feedback:

So if you give feedback that seems unfair, you know … they’ll turn around and say, ‘What are you talking about’? They’re going to react back if your feedback is not clear. I think a lot of them [the students] appreciate the honesty. (A2,D2)

A2 acknowledges that her identity as a native English speaker has given her the advantage to publish extensively in international journals because of her high level of English proficiency and her access to ‘data from the US and from Australia which are more marketable’ (A2,D2). At the same time, as a native English speaker, she has empathy for her Japanese colleagues who struggle to write proficiently in English and some who even ‘pay thousands of dollars to have their work translated’ (A2,D2). Therefore, when giving feedback as a peer reviewer, she tries not to make a judgement on an author’s English proficiency and will not reject a paper based on the standard of English alone. Finally, as a first-generation scholar without any previous connections to academia, she struggles with belonging and self-confidence. As a result she notes that it usually takes her a long time to complete a review because she would like to be sure what she is saying is ‘right or constructive and is not on the wrong track’ (A2,D2).

Implications and future directions

In investigating the manifestations of the authors’ feedback literacy development, and the ecological systems in which this development occurs, this study unpacks the various sources of influence behind our feedback behaviours as two relatively new but highly commended peer reviewers. The findings show that our feedback literacy development is highly personalised and contextualised, and the sources of influence are diverse and interconnected, albeit largely informal. Our peer-review practices are influenced by our experiences within academia, but influences are much broader and begin much earlier. Peer-review skills were enhanced through direct experience not only in peer review but also in other activities related to the peer-review process, and as such more hands-on, on-site feedback training for peer reviewers may be more appropriate than knowledge-based training. The authors gain valuable insights from seeing the reviews of others, and as this is often not possible until scholars take on more senior roles within journals, co-reviewing is a potential way for ECRs to gain experience (McDowell et al., 2019). We draw practical and moral support from various communities, particularly online to promote “intellectual candour”, which refers to honest expressions of vulnerability for learning and trust building (Molloy and Bearman, 2019, p. 32); in response to this finding we have developed an online community of practice, specifically as a space for discussing issues related to peer review (a Twitter account called “Scholarly Peers”). Importantly, our review practices are a product not only of how we review, but why we review, and as such training should not focus solely on the mechanics of review, but extend to its role within academia, and its impact not only on the quality of scholarship, but on the growth of researchers.

The significance of this study is its insider perspective, and the multifaceted framework that allows the capturing of the complexity of factors that influence individual feedback literacy development of two recognised peer reviewers. It must be stressed that the findings of this study are highly idiosyncratic, focusing on the experiences of only two peer reviewers and the educational research discipline. While the research design is such that it is not an attempt to describe a ‘typical’ or ‘expected’ experience, the scope of the study is a limitation, and future research could be expanded to studies of larger cohorts in order to identify broader trends. In this study, we have not included the reviewer reports themselves, and these reports provide a potentially rich source of data, which will be a focus in our continued investigation in this area. Further research could also investigate the role that peer-review training courses play in the feedback literacy development and practices of new and experienced peer reviewers. Since journal peer review is a communication process, it is equally important to investigate authors’ perspectives and experiences, especially pertaining to how authors interpret reviewers’ feedback based on the ways that it is written.

Data availability

Because of the sensitive nature of the data these are not made available.

Change history

26 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00996-3

References

Abedi Asante L, Abubakari Z (2020) Pursuing PhD by publication in geography: a collaborative autoethnography of two African doctoral researchers. J Geogr High Educ 45(1):87–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2020.1803817

Boud D, Dawson P (2021). What feedback literate teachers do: An empirically-derived competency framework. Assess Eval High Educ. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1910928

Bronfenbrenner U (1986) Ecology of the family as a context for human development. Res Perspect Dev Psychol 22:723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Carless D, Boud D (2018) The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess Eval High Educ 43(8):1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Carless D, Winstone N (2020) Teacher feedback literacy and its interplay with student feedback literacy. Teach High Educ, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372

Chang H, Ngunjiri FW, Hernandez KC (2013) Collaborative autoethnography. Left Coast Press

Cheung D (2000) Measuring teachers’ meta-orientations to curriculum: application of hierarchical confirmatory factor analysis. The J Exp Educ 68(2):149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970009598500

Chong SW (2021a) Improving peer-review by developing peer reviewers’ feedback literacy. Learn Publ 34(3):461–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1378

Chong SW (2021b) Reconsidering student feedback literacy from an ecological perspective. Assess Eval High Educ 46(1):92–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1730765

Chong SW (2019) College students’ perception of e-feedback: a grounded theory perspective. Assess Eval High Educ 44(7):1090–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1572067

Chong SW (2018) Interpersonal aspect of written feedback: a community college students’ perspective. Res Post-Compul Educ 23(4):499–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2018.1526906

Corden A, Sainsbury R (2006) Using verbatim quotations in reporting qualitative social research: the views of research users. University of York Social Policy Research Unit

Ellis C, Adams TE, Bochner AP (2011) Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Soc Res, 12:273–290

Ellis C, Bochner A (1996) Composing ethnography: Alternative forms of qualitative writing. Sage

Freda MC, Kearney MH, Baggs JG, Broome ME, Dougherty M (2009) Peer reviewer training and editor support: results from an international survey of nursing peer reviewers. J Profession Nurs 25(2):101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2008.08.007

Fulcher G (2012) Assessment literacy for the language classroom. Lang Assess Quart 9(2):113–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2011.642041

Gee JP (1999) Reading and the new literacy studies: reframing the national academy of sciences report on reading. J Liter Res 3(3):355–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862969909548052

Gravett K, Kinchin IM, Winstone NE, Balloo K, Heron M, Hosein A, Lygo-Baker S, Medland E (2019) The development of academics’ feedback literacy: experiences of learning from critical feedback via scholarly peer review. Assess Eval High Educ 45(5):651–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1686749

Hains-Wesson R, Young K (2016) A collaborative autoethnography study to inform the teaching of reflective practice in STEM. High Educ Res Dev 36(2):297–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1196653

Han Y, Xu Y (2019) Student feedback literacy and engagement with feedback: a case study of Chinese undergraduate students. Teach High Educ, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1648410

Heesen R, Bright LK (2020) Is Peer Review a Good Idea? Br J Philos Sci, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axz029

Hollywood A, McCarthy D, Spencely C, Winstone N (2019) ‘Overwhelmed at first’: the experience of career development in early career academics. J Furth High Educ 44(7):998–1012. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1636213

Horn SA (2016) The social and psychological costs of peer review: stress and coping with manuscript rejection. J Manage Inquiry 25(1):11–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492615586597

Hughes S, Pennington JL, Makris S (2012) Translating Autoethnography Across the AERA Standards: Toward Understanding Autoethnographic Scholarship as Empirical Research. Educ Researcher, 41(6):209–219

Kandiko CB(2010) Neoliberalism in higher education: a comparative approach. Int J Art Sci 3(14):153–175. http://www.openaccesslibrary.org/images/BGS220_Camille_B._Kandiko.pdf

Keashly L, Neuman JH (2010) Faculty experiences with bullying in higher education-causes, consequences, and management. Adm Theory Prax 32(1):48–70. https://doi.org/10.2753/ATP1084-1806320103

Kelly J, Sadegieh T, Adeli K (2014) Peer review in scientific publications: benefits, critiques, & a survival guide. J Int Fed Clin Chem Labor Med 25(3):227–243. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975196/

Kumar KL (2020) Understanding and expressing academic identity through systematic autoethnography. High Educ Res Dev, https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1799950

Lapadat JC (2017) Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qual Inquiry 23(8):589–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417704462

Levi T, Inbar-Lourie O (2019) Assessment literacy or language assessment literacy: learning from the teachers. Lang Assess Quarter 17(2):168–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2019.1692347

London MS, Smither JW (2002) Feedback orientation, feedback culture, and the longitudinal performance management process. Hum Res Manage Rev 12(1):81–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(01)00043-2

Malecka B, Boud D, Carless D (2020) Eliciting, processing and enacting feedback: mechanisms for embedding student feedback literacy within the curriculum. Teach High Educ, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1754784

Mavrogenis AF, Quaile A, Scarlat MM (2020) The good, the bad and the rude peer-review. Int Orthopaed 44(3):413–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04504-1

McDowell GS, Knutsen JD, Graham JM, Oelker SK, Lijek RS (2019) Co-reviewing and ghostwriting by early-career researchers in the peer review of manuscripts. ELife 8:e48425. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.48425

Merga MK, Mason S, Morris JE (2018) Early career experiences of navigating journal article publication: lessons learned using an autoethnographic approach. Learn Publ 31(4):381–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1192

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd edn.). Sage

Molloy E, Bearman M (2019) Embracing the tension between vulnerability and credibility: ‘Intellectual candour’ in health professions education. Med Educ 53(1):32–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13649

Molloy E, Boud D, Henderson M (2019) Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assess Eval High Educ 45(4):527–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

Neal JW, Neal ZP (2013) Nested or networked? Future directions for ecological systems theory. Soc Dev 22(4):722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12018

Noble C, Billett S, Armit L, Collier L, Hilder J, Sly C, Molloy E (2020) “It’s yours to take”: generating learner feedback literacy in the workplace. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 25(1):55–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09905-5

Price M, Rust C, O’Donovan B, Handley K, Bryant R (2012) Assessment literacy: the foundation for improving student learning. Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development

Silbiger NJ, Stubler AD (2019) Unprofessional peer reviews disproportionately harm underrepresented groups in STEM. PeerJ 7:e8247. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8247

Starck JM (2017) Scientific peer review: guidelines for informative peer review. Springer Spektrum

Steelman LA, Wolfeld L (2016) The manager as coach: the role of feedback orientation. J Busi Psychol 33(1):41–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9473-6

Stiggins RJ (1999) Evaluating classroom assessment training in teacher education programs. Educ Meas: Issue Pract 18(1):23–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1999.tb00004.x

Street B (1997) The implications of the ‘new literacy studies’ for literacy Education. Engl Educ 31(3):45–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-8845.1997.tb00133.x

Sughrua WM (2019) A nomenclature for critical autoethnography in the arena of disciplinary atomization. Cult Stud Crit Methodol 19(6):429–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708619863459

Sutton P (2012) Conceptualizing feedback literacy: knowing, being, and acting. Innov Educ Teach Int 49(1):31–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.647781

Tynan BR, Garbett DL (2007) Negotiating the university research culture: collaborative voices of new academics. High Educ Res Dev 26(4):411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701658617

Vygotsky LS (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press

Wall S (2006) An autoethnography on learning about autoethnography. Int J Qual Methods 5(2):146–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500205

Warne V (2016) Rewarding reviewers-sense or sensibility? A Wiley study explained. Learn Publ 29:41–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1002

Wilkinson S (2019) The story of Samantha: the teaching performances and inauthenticities of an early career human geography lecturer. High Educ Res Dev 38(2):398–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1517731

Winstone N, Carless D (2019) Designing effective feedback processes in higher education: a learning-focused approach. Routledge

Winstone NE, Mathlin G, Nash RA (2019) Building feedback literacy: students’ perceptions of the developing engagement with feedback toolkit. Front Educ 4:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00039

Xu Y, Carless D (2016) ‘Only true friends could be cruelly honest’: cognitive scaffolding and social-affective support in teacher feedback literacy. Assess Eval High Educ 42(7):1082–1094. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1226759

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

We acknowledge that research data are collected from human subjects (from the two authors), such data are collected in accordance with the standards and guidelines of the School Research Ethics Committee at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work, Queen’s University Belfast (Ref: 005_2021).

Informed consent

Since the participants are the two authors, there is no informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chong, S.W., Mason, S. Demystifying the process of scholarly peer-review: an autoethnographic investigation of feedback literacy of two award-winning peer reviewers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 266 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00951-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00951-2

- Springer Nature Limited