Abstract

Childhood parental death has been associated with adverse health, social and educational outcomes. Studies on long-term outcomes are in general scarce and there is little evidence on the long-term impact on anti-social behaviour. This study takes advantage of high-quality register data to investigate risk of violent crime in relation to childhood parental death in a large national cohort covering the entire Swedish population born in 1983–1993 (n = 1,103,656). The impact of parental death from external (suicides, accidents, homicides) and natural causes on risk for violent crime from age 15 to 20–30 years, considering multiple aspects of the rearing environment (including parental psychiatric disorders and criminal offending), was estimated through Cox regression. Unadjusted hazard ratios associated with parental death from external causes ranged between 2.20 and 3.49. For maternal and paternal death from external causes, adjusted hazard ratios were 1.26 (95% confidence intervals: 1.04–1.51) and 1.44 (95% confidence intervals: 1.32–1.57) for men, and 1.47 (95% confidence intervals: 1.05–2.06) and 1.51 (95% confidence intervals: 1.27–1.78) for women. With the exception of maternal death among women (hazard ratio 1.26, 95% confidence intervals: 1.03–1.53), parental death from natural causes was not associated with increased risks in adjusted models. The results underscore the importance of preventive interventions to prevent negative life-course trajectories, particularly when death is sudden and clustered with other childhood adversities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

About 4% of all children in Sweden experience the death of a parent before their eighteenth birthday (Berg et al., 2016), and similar numbers are seen in other western countries (Parsons, 2011; Social Security Administration, 2000). The loss of a parent is a potentially traumatic life event that may affect the life of the child in several ways, and has been associated with adverse health, social and educational outcomes throughout the life course (Li et al., 2014, Cerel et al., 2006; Berg et al., 2016; Parsons, 2011; Hoeg et al., 2018). An increased risk of psychiatric problems during the first years following a parent’s death has been seen in children with experience of parental death (Dowdney, 2000; Agerbo et al., 2002; Cerel et al., 2006; Brent et al., 2009). Bereaved children and adolescents have also been shown to have higher frequencies of health risk behaviours, e.g., behaviours that contribute to unintentional injury or violence (Hamdan et al., 2012), and to be at greater risk for alcohol and substance abuse (Hamdan et al., 2013), school failure and educational achievement (Hoeg et al., 2018; Berg et al., 2014). Previous studies on long-term consequences of childhood parental death also suggest that the experience of a parent’s death during childhood may have implications for health and well-being well in adulthood, e.g., with increased risks of depression and other affective disorders (Berg et al., 2016; Appel et al., 2013), suicidal behaviour (Rostila et al., 2016; Serafini et al., 2015), drug use disorder (Giordano et al., 2014) and premature mortality (Rostila and Saarela 2011; Li et al., 2014). However, studies on potential long-term impact of childhood parental death are in general scarce and there are few studies on long-term consequences for anti-social behaviour and criminal offending among bereaved offspring. Violence is an important public health concern and violent criminal convictions are also associated with increased risk of continuity of offending and severe consequences such as suicidal behaviour and premature mortality (Steeg et al., 2019). In this study, we aimed to investigate the possible association between parental death and violent criminal offending.

In addition to the importance of genetic factors (Rhee and Waldman, 2002), previous evidence demonstrate that the rearing environment has a major influence on the risk for criminal offending (Kendler et al., 2016; Kendler et al., 2015; Farrington, 1995). Parental death, and in particular deaths caused by external factors, i.e., suicides, accidents and homicides, is associated with higher levels of criminality, psychiatric health problems and substance abuse in the deceased as well as in the surviving parent (Melhem et al., 2008; Rostila et al., 2016). A recent Australian study (Malvaso et al., 2018), which examined adverse childhood events among young people in detention, showed that individuals who had lost a parent had over two times the odds of having a family member with a substance use problem. In previous studies, we have demonstrated that the increased risk of adverse outcomes is mainly seen in children and adolescents who lose their parent to death from external causes, most likely due to the combination of familial risk factors with the loss itself (Berg et al., 2014; Berg et al., 2016; Rostila et al., 2016).

During the last decades, a large number of studies have provided evidence for an association between adverse childhood events and health and behavioural problems throughout the life course (Fellitti et al., 1998; Anda et al., 2006; Hughes et al., 2017). The concept of adverse childhood experiences include life events relating to abuse and neglect, household mental illness and substance abuse, domestic violence, living with a household member who has been incarcerated and parental separation or divorce (Felitti et al., 1998). Originally, this framework did not include the experience of parental death during childhood or adolescence but this potentially traumatic event is increasingly being included in research on childhood adversity (see, e.g., Malvaso et al., 2018 and Björkenstam et al., 2017).

Anti-social and violent behaviour can be passed on between generations and violent offending has been shown to cluster within families (Putkonen et al., 2007; Frisell et al., 2011). Offspring to parents with substance abuse and mental health problems have also been shown to be at elevated risk of violent criminal behaviour later in life (Dean et al., 2012; Mok et al., 2016; Christoffersen and Soothill, 2003; Besemer, 2014; Frisell et al., 2011). This intergenerational transmission is probably due to a combination of genetic, social and environmental factors. Thus, higher rates of offspring criminal offending, and in particular violent criminal offending, could be expected in relation to parent’s death from external causes, compared with deaths from natural causes. Also, associations between parental death, in particularly deaths from external causes, and offspring involvement in violent crime could be expected to be explained at least partly by parental psychopathology.

Thus, in the light of these previous findings we were particularly interested in investigating the possible differential impact of parental death from natural and external causes and whether a potential association between parents’ externally caused deaths were associated with offspring violent criminal offending after adjustment for a large number of potentially confounding factors. There are few previous longitudinal studies on this topic and the results are conflicting (Feigelman et al., 2016; Kendler et al., 2014; Wilcox et al., 2010; Sauvola et al., 2002). In a study based on survey data, no differences were seen between the bereaved and the non-bereaved groups with regard to self-reported criminal involvement in young adulthood (Feigelman et al., 2016). On the other hand, in a previous Swedish register-based study, an increased risk of violent criminal convictions was seen among bereaved offspring, which was not, quite surprising, associated with parental cause of death (Wilcox et al., 2010). Other studies have not separately analysed effects by cause of death (Sauvola et al., 2002; Kendler et al., 2014) and little is known about the contribution of parental psychopathology to these association. Thus, with this study we intend to fill this gap in the existing literature. Furthermore, there is a lack of knowledge on the potential different effects of maternal versus paternal death, and since previous studies have focused on men or have not performed separate analyses of men and women (Wilcox et al., 2010; Sauvola et al., 2002), little is known about associations in women. In addition to potential gender differences, the child’s age at the time of death of the parent is also important to consider. It is possible that the effect of parental loss differs between different stages in childhood, i.e., reflecting certain sensitive periods or developmental stages, and that consequences from parental death differ between younger and older children. Potential differences could also reflect time since the death of the parent, e.g., children that lose a parent at younger ages could have more time to resolve their grief and cope with the loss.

The current study takes advantage of unique longitudinal high-quality register data from a national cohort consisting of more than 1,000,000 Swedish men and women. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between parental death before age 15 (since 15 is the age of criminal responsibility in Sweden) and violent crime from age 15 to 20–30 years. Specifically, we aimed to analyse the separate impact of parental death from natural and external causes and to what extent such associations may be explained by parental psychopathology, i.e., paternal and maternal violent offending, psychiatric disorders and substance abuse. Furthermore, we were also interested in analysing whether similar associations were seen in men and women and whether there were differences depending on the child’s age at the time of death of the parent.

Methods

This study is based on information from Swedish national registers. Linkage of registers is made possible by use of the unique personal identity number assigned to all Swedish residents at birth or at time of immigration. In data sets available to researchers, the personal identity numbers are replaced by random reference numbers and all data are anonymous.

Our study population consisted of all individuals born in Sweden between 1983 and 1993 (according to the Medical Birth Register) with two birth parents in the Multi-Generation Register (n = 1,103,656), who were alive at age 15 and had no record of emigration.

Childhood parental death

Information on parents’ time and cause of death was retrieved from the Cause of Death Register. Childhood parental death was defined as death of a parent before age 15. Deaths were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) as deaths caused by natural causes, i.e., diseases (ICD-8 code: 0000–7969; ICD-9 code: 000–796; and ICD-10 code: A00-R99) or deaths caused by external causes, i.e., accidents, homicide or suicides (ICD-8 code: 8000–9999; ICD-9 code: 800–999; and ICD-10 code: V01-Y98).

Violent crime

Information of all convictions for violent crime between 1998 and 2013 was retrieved from the Crime Register from age 15 (the age of criminal responsibility in Sweden). Violent crime was defined as homicide, assault, robbery, arson, any sexual offence (rape, sexual coercion, child molestation, indecent exposure, or sexual harassment), illegal threats, or intimidation. This definition does not include burglary and other property offences, traffic offences, and drug offences and corresponds to definitions used in previous studies (Fazel and Grann, 2006; Fazel et al., 2009). Violent crime was defined as at least one conviction from age 15 until 2013 when the study population was aged 20–30 years.

Covariates

The Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies was used to retrieve information on sociodemographic and socioeconomic covariates, including gender, birth year, geographic residency, parental country of birth and educational level, and social welfare benefits. Recipiency of social welfare benefits was defined as a dichotomous indicator of whether or not the parent had received economic assistance of any amount during the year when the child had his/her 15th birthday.

Information on parental violent criminality was retrieved from the Crime Register from 1973 (i.e., from start of the register) and included in the analyses in two separate variables; having been convicted for a violent crime at least once before the child was born (all parents) and having been convicted for a violent crime at least once when the child was aged 0–14 years old (surviving parents only). Parental substance abuse and psychiatric disorders were included in the analyses in a corresponding manner. Parental psychiatric disorders were defined as at least one hospitalisation with a main diagnosis indicating a psychiatric disorder (not related to substance abuse) and/or self-inflicted injury, using information from The Hospital Discharge Register. Parental substance abuse problems were defined by at least one hospital admission with an ICD diagnosis indicating alcohol or illicit drug use.

Statistical analyses

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for criminal convictions, in relation to childhood parental death. Person time of follow-up was accumulated from the 15th birthday until the date of the first violent conviction, date of death or end of follow-up in December 2013. Maternal and paternal death from natural and external causes were analysed separately. Previous studies (see, e.g., Rostila and Saarela, 2011; Berg et al., 2016; Rostila et al., 2016) indicate that associations may differ between genders and depending on age at death of the parent and we also analyse the importance these factors. All analyses were performed separately for men and women and to evaluate whether there was a statistically significant subgroup difference, gender was further investigated in multiplicative interaction analyses. In order to analyse whether associations differed depending on age at loss we analysed age of the child at the time of parental loss in three categories: 0–5 years, 6–10 years and 11–14 years. To account for potential clustering within sibling groups, robust variance estimates were computed.

In the multivariate models, data were analysed in three different models. Model 1 included year of birth. Model 2 included year of birth, geographic residency, parental country of birth and parent’s educational level (for bereaved families the surviving parent’s highest educational level); sociodemographic covariates that should be relatively unaffected by a parent’s death and therefore considered as potential confounders. In model 3 information on two sets of dichotomous indicators of psychosocial problems in the family was added: violent crime, psychiatric disorder, and substance abuse in both parents before the child was born; and violent crime, psychiatric disorder, substance abuse and social welfare benefits (as an indicator of the post death economic status of the family) when the child was 0–14 years old.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

In our study population, 2.3% of children under the age of 15 experienced the death of a parent. Paternal deaths constituted 72% of all deaths, and fathers were more likely, compared with mothers, to die from external causes; 42% of paternal deaths and 26% of maternal deaths were caused by suicides, accidents and homicides. Parental deaths caused by external factors were more common among younger children (Table 1). Parental death was associated with lower educational levels in surviving parents and surviving parents were more likely to receive social welfare benefits. Parental violent criminal offending and hospitalisations for psychiatric disorders and substance abuse were more common in families where a parent died, and in particular in families where the parent died from external causes. Higher levels of these parental problems were seen in both parents before the child was born, as well as in the surviving parent when the child was 0–14 years old (Table 1).

Violent crimes were more common in men and women with childhood experience of parental death, compared with children without this experience (Table 2). In the reference group, 5.6% of the men and 1.2% of the women had been convicted of a violent crime at least once between the ages 15 to 20–30 years. Corresponding numbers among individuals who had lost a parent were 9.9% among men and 2.6% among women. The highest levels of violent crime were seen for individuals who lost a parent to death from external causes. Violent criminal convictions were associated with lower parental educational levels and social welfare recipiency. Violent crimes were three to four times more common in men and four to seven times more common in women whose mother or father had been convicted of a violent crime. Having been convicted of a violent crime was also far more common in individuals from families where parents had been admitted to a hospital because of a psychiatric disorder or substance abuse (Table 2).

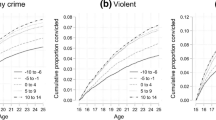

In models adjusted only for birth year, maternal as well as paternal death from external causes were associated with increased HRs of violent crime, with HRs of 2.20, 95% CI 1.82–2.66 (maternal death) and 2.67, 95% CI 2.44–2.91 (paternal death) for men. For women corresponding HRs were 3.49 (2.51–4.87) and 3.26 (2.76–3.84) (Table 3). Adjustment for sociodemographic factors and parent’s educational level attenuated the HRs, but both maternal and paternal death from external causes were associated with two to three times higher HRs of violent criminal offending in these adjusted models. Paternal death from natural causes was also associated with increased HR, although on a lower level, whereas maternal death from natural causes was not associated with increased risk of violent criminal offending in offspring, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and parental educational level. HRs were considerably attenuated after additional adjustment for parental violent crime, and parental psychiatric disorder and substance abuse. For men, HR of violent criminal convictions were 1.26 (1.04–1.51) in relation to maternal death from external causes and 1.44 (1.32–1.57) for paternal death from external causes. In women, corresponding HRs were 1.47 (1.05–2.06) and 1.51 (1.27–1.78). In fully adjusted models, paternal natural death was only associated with an increased risk of violent criminal offending in women (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.03–1.53). Interaction analyses showed no effect modification of gender (p > 0.05).

There were only small differences with regard to the child’s age at the time of death of the parent (Table 4). Additional analyses were also performed for a small group of children consisting of 285 individuals (0.03%) who lost both parents before age 15. For these individuals, HR for violent crime were 1.69 (1.07–2.68) (adjusted for age, sex, region of residency and parental country of birth), and 0.91 (0.57–1.44) when additionally adjusted for parental violent crime, psychiatric disorder and substance abuse before the child was born.

Discussion

In this register-based study in a national cohort, parental death from external causes, i.e., suicides, accidents and homicides, was associated with an increased risk of violent crime. Increased risks were seen in both men and women, for maternal as well as paternal death and regardless of the child’s age at the time of death of the parent. Violent criminal offending, psychiatric disorders and substance abuse in the parents explained a large part of the association with violent crime in their offspring, underlining the importance of linked and accumulated familial psychosocial risk factors and adverse childhood events in the negative life-course trajectories of bereaved children and adolescents.

Our findings demonstrate a clear difference between parental deaths from natural versus external causes. There is consistent evidence from twin and adoption studies for a strong genetic component in the complex aetiology of criminal behaviour (Rhee and Waldman, 2002, Kendler et al., 2014). Accordingly, associations between parental deaths from violent causes, such as suicides and accidents, and risk of violent crime in offspring may be explained by genetic vulnerability and impulsive-aggressive traits shared within the family. To, as far as possible in available data, account for the heredity of criminal behaviour we adjusted for violent criminal offending, psychiatric disorders and substance abuse in parents, both before and after the birth of the child. Our findings suggest that much of the effect can be attributed to parental psychopathology associated primarily with external causes of death. The results also suggest that the increased risk of violent criminal offending in bereaved children reflect genetic vulnerability in combination with social and psychosocial factors. Our findings in relation to parental death from external causes and the clustering of adverse events fit well within the existing literature of adverse childhood experiences. Previous studies have demonstrated that poorer outcomes in individuals exposed to childhood adversity are seen particularly when events are accumulated (Hughes et al., 2017; Björkenstam et al., 2018).

Our results demonstrate that the effect of parental death is stronger for deaths that are due to suicides, accidents and homicides, i.e., deaths that are sudden and unexpected. Sudden and unexpected deaths can also be particularly stressful and may contribute to a more complicated grief and even post traumatic stress (Kristensen et al., 2012; Mccloskey and Walker, 2000), and also to an increased risk of drug use disorder (Giordano et al., 2014) especially when coupled with post-traumatic stress (Reed et al., 2007). The association between substance abuse and criminal offending and a high prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and trauma history in young offenders (Foy et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2013), have been emphasised in previous research.

Thus, taken together, our results suggest that there is an effect of the death itself and that parental death, in particularly when death is sudden and unexpected, should be considered a potentially traumatic childhood event. The importance of our findings are further emphasised by clearly demonstrating the association between parental death from external causes and other adverse childhood experiences, which support the call for inclusion of parental death in a broader definition of this concept, as discussed previously (see, e.g., Malvaso et al., 2018).

Our findings can also be discussed through the lens of life-course theories. Social development theories argue that the path from childhood risk factors to adult criminality should be understood as a life-course process (Hawkins, 1996). The so called ‘pathway model’ (Kuh et al., 2003) emphasises that different exposures are linked to each other, with one event leading to another. Accordingly, the death of a parent could be seen as a fundamental exposure that sets off a chain of negative events, such as school failure and substance abuse. Our findings can also be understood through the ‘accumulation model’, which suggests that disadvantages tend to cluster and accumulate over the life course (Kuh et al., 2003). The experience of sudden and unexpected death in childhood is often part of such broader clustering of adverse childhood exposures. Previous research has demonstrated that various childhood adversities are strongly related to increased risk of juvenile delinquency and criminal offending in young adulthood (Mok et al., 2016; Besemer, 2014; Christoffersen and Soothill, 2003; Baglivio et al., 2014; Duke et al., 2010). The death of a parent may be part of such a chain of events or clustered with other adverse experiences, but may also in itself be associated with anti-social or aggressive behaviour, especially in the case of prolonged and complicated grief.

Parental death is more common in socioeconomically disadvantaged families (Berg et al., 2016; Fauth et al., 2009), and even though childhood socioeconomic disadvantage has been associated with an increased risk of criminal offending (Fergusson et al., 2004), socioeconomic factors explained only a small part of the association with violent crime. These findings are in line with previous research, suggesting that familial psychosocial risk factors, such as parental criminality and the quality of the parent-child relationship more strongly contribute to these associations (Sariaslan et al., 2014). In addition to pre-existing psychosocial problems in the bereaved family, the surviving parent has to deal with his/her own grief and possibly psychological problems. These kinds of problems may influence parenting through the impairment of emotional support, guidance and supervision of the children. Previous studies have emphasised the important influence of parental behaviour and parenting style for anti-social behaviour (Hoeve et al., 2009; Rhee and Waldman, 2002); and poor parental control and supervision has repeatedly been associated with offspring criminal offending (Schroeder et al., 2010; Farrington, 2015). Psychopathology in parents and other indicators for childhood household dysfunction are also associated with increased risk of physical abuse and neglect (Dube et al., 2001), known risk factors for violent and anti-social behaviour (Farrington, 2005; Wilson et al., 2009).

The strengths of the current study include the use of high-quality national register data and the longitudinal design. Another strength is the large sample size (covering the entire Swedish population born in 1983–1993), which made it possible to analyse associations in women, despite the much lower crime rates among women, and to separately investigate maternal and paternal death, as well as cause of parental death. In addition, one important strength is the possibility to adjust for important family and parental factors, including psychiatric disorders and history of violent criminal offending (even before birth of the child).

However, our study also has limitations. Violent crime is measured using official record data and a large proportion of undetected and unreported crimes or crimes that do not result in convictions may result in misclassification bias. Since we have no reason to believe that this misclassification would differ between bereaved and non-bereaved individuals, such non-differential misclassification would lead to a dilution of the associations. Another limitation of the current study is that information on child abuse and neglect was not available from the Swedish national registers. The use of hospital admissions as indicator of parental mental health problems and substance abuse should also be noted as a limitation since this measure does not capture cases that are not severe enough to cause a hospital admission, and thus the contributing effect of such parental psychosocial problems may be underestimated.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate the importance of support for bereaved families in order to prevent negative life-course trajectories of children and adolescents with experience of parental death, particularly when the death is sudden and unexpected and clustered with other childhood adversities. Bereavement following sudden and violent death seem to be more complicated and require different interventions compared with bereavement following parental death from natural causes where the link to other adverse childhood experiences is weak and the consequences over the life course seem to be less serious. The effectiveness of some types of bereavement interventions has, however, been questioned (Currier et al., 2007) and more research on interventions for bereaved children is warranted.

Our results also emphasise that preventive efforts should address childhood adversity and problems in the family environment since parental death is often clustered with other adverse childhood events. The important issue that adverse outcomes for children with such experiences can represent adverse childhood experiences for the next generation was discussed in a recent review and meta-analyses (Hughes et al., 2017). These findings further emphasise the importance of increased focus on prevention of childhood adversity, especially when accumulated (Hughes et al., 2017). Children growing up under difficult circumstances show, however, remarkable resilience. For the individual child, different protective factors, positive experiences and psychological resilience, the individual ability to cope with adversity or trauma can result in positive long-term outcomes despite exposure to childhood adversity (Poole et al., 2017; Bonanno, 2004). Thus, increased focus on factors that promote resilience is needed both in research, as well as in policy and prevention efforts.

Our findings demonstrate an increased risk of violent crime in adolescents and young adults with experience of childhood parental death, primarily when the death was caused by external factors and clustered with other childhood adversities. This association was partly accounted for by family characteristics that may both precede and determine parental death and also accumulate after the death, but an increased risk of violent crime was seen also after adjustment for violent criminal offending, psychiatric disorders and substance abuse in the parents.

Data availability

The dataset used for this study is based on linked data retrieved from national Swedish routine registers (held by Statistics Sweden and the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare). Sharing of the data is restricted by Swedish data protection laws, according to which administrative data is made available for specific research projects. Thus, the data used for this study cannot be shared with other researchers.

References

Agerbo E, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2002) Familial, psychiatric, and socioeconomic risk factors for suicide in young people: nested case-control study. BMJ 325(7355):74

Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH (2006) The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 256(3):174–186

Appel CW, Johansen C, Deltour I, Frederiksen K, Hjalgrim H, Dalton SO, Dencker A, Dige J, Boge P, Rix BA, Dyregrov A, Engelbrekt P, Helweg E, Mikkelsen OA, Hoybye MT, Bidstrup PE (2013) Early parental death and risk of hospitalization for affective disorder in adulthood. Epidemiology 24(4):608–615

Baglivio M, Swartz K, Sayedul Huq M, Sheer A, Hardt N (2014) The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. J Juv Justice 3.

Berg L, Rostila M, Hjern A (2016) Parental death during childhood and depression in young adults–a national cohort study J Child Psychol Psychiatry 57(9):1092–1098

Berg L, Rostila M, Saarela J, Hjern A (2014) Parental death during childhood and subsequent school performance Pediatrics 133(4):682–689

Besemer S (2014) The impact of timing and frequency of parental criminal behaviour and risk factors on offspring offending. Psychol, Crime Law 20:78–99

Björkenstam C, Kosidou K, Björkenstam E (2017) Childhood adversity and risk of suicide: cohort study of 548 721 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. BMJ 357:j1334

Björkenstam E, Hjern A, Björkenstam C, Kosidou K (2018) Association of cumulative childhood adversity and adolescent violent offending with suicide in early adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry 75(2):185–193

Bonanno GA (2004) Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the humanc capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol 59(1):20–28

Brent D, Melhem N, Donohoe MB, Walker M (2009) The incidence and course of depression in bereaved youth 21 months after the loss of a parent to suicide, accident, or sudden natural death. Am J Psychiatry 166(7):786–794

Cerel J, Fristad MA, Verducci J, Weller RA, Weller EB (2006) Childhood bereavement: psychopathology in the 2 years postparental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 45(6):681–690

Christoffersen MN, Soothill K (2003) The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: a cohort study of children in Denmark. J Subst Abus Treat 25(2):107–116

Currier JM, Holland JM, Neimeyer RA (2007) The effectiveness of bereavement interventions with children: a meta-analytic review of controlled outcome research. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 36(2):253–259

Dean K, Mortensen PB, Stevens H, Murray RM, Walsh E, Agerbo E (2012) Criminal conviction among offspring with parental history of mental disorder. Psychol Med 42(3):571–581

Dowdney L (2000) Childhood bereavement following parental death. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41(7):819–830

Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Giles WH (2001) Growing up with parental alcohol abuse: exposure to childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abus Negl 25(12):1627–1640

Duke NN, Pettingell SL, Mcmorris BJ, Borowsky IW (2010) Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics 125(4):e778–e786

Farrington DP (1995) The Twelfth Jack Tizard Memorial Lecture. The development of offending and antisocial behaviour from childhood: key findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 36(6):929–964

Farrington DP (2005) Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clin Psychol Psychother 12(3):177–190

Farrington DP (2015) Prospective longitudinal research on the development of offending. Aust NZ J Criminol 48(3):314–335

Fauth B, Thompson M, Penny A (2009) Associations between childhood bereavement and children’s background, experiences and outcomes. Secondary analysis of the 2004 Mental Health of Children and Young People in Great Britain data. National Children’s Bureau, London

Fazel S, Grann M (2006) The population impact of severe mental illness on violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 163(8):1397–1403

Fazel S, Langstrom N, Hjern A, Grann M, Lichtenstein P (2009) Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA 301(19):2016–2023

Feigelman W, Rosen Z, Joiner T, Silva C, Mueller AS (2016) Examining longer-term effects of parental death in adolescents and young adults: evidence from the national longitudinal survey of adolescent to adult health. Death Stud 41:1–11

Felitti V, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss Mp, Marks J (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med 14(4):245–258

Fergusson D, Swain-Campbell N, Horwood J (2004) How does childhood economic disadvantage lead to crime? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45(5):956–966

Foy DW, Ritchie IK, Conway AH (2012) Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress, and comorbidities in female adolescent offenders: findings and implications from recent studies. Eur J Psychotraumatol 3:17247

Frisell T, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N (2011) Violent crime runs in families: a total population study of 12.5 million individuals. Psychol Med 41(1):97–105

Giordano GN, Ohlsson H, Kendler KS, Sundquist K, Sundquist J (2014) Unexpected adverse childhood experiences and subsequent drug use disorder: a Swedish population study (1995–2011). Addiction 109(7):1119–1127

Hamdan S, Mazariegos D, Melhem NM, Porta G, Payne MW, Brent DA (2012) Effect of parental bereavement on health risk behaviors in youth: a 3-year follow-up. Arch Pedia Adolesc Med 166(3):216–223

Hamdan S, Melhem NM, Porta G, Song MS, Brent DA (2013) Alcohol and substance abuse in parentally bereaved youth. J Clin Psychiatry 74(8):828–833

Hawkins DJ (1996) Delinquency and crime: current theories. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY

Hoeg BL, Johansen C, Christensen J, Frederiksen K, Dalton SO, Boge P, Dencker A, Dyregrov A, Bidstrup PE (2018) Does losing a parent early influence the education you obtain? A nationwide cohort study in Denmark. J Public Health (Oxf).

Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, Van Der Laan PH, Smeenk W, Gerris JR (2009) The relationship between parenting and delinquency: a meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 37(6):749–775

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, Dunne MP (2017) The effect of multiple adverse childhood expereinces on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2:e356–e366

Kendler KS, Larsson Lonn S, Morris NA, Sundquist J, Langstrom N, Sundquist K (2014) A Swedish national adoption study of criminality. Psychol Med 44(9):1913–1925

Kendler KS, Morris NA, Ohlsson H, Lonn SL, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2016) Criminal offending and the family environment: Swedish national high-risk home-reared and adopted-away co-sibling control study. Br J Psychiatry 209(4):294–299

Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Morris NA, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2015) A Swedish population-based study of the mechanisms of parent-offspring transmission of criminal behavior. Psychol Med 45(5):1093–1102

Kristensen P, Weisaeth L, Heir T (2012) Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: a review. Psychiatry 75(1):76–97

Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C (2003) Life course epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health 57(10):778–783

Li J, Vestergaard M, Cnattingius S, Gissler M, Bech BH, Obel C, Olsen J (2014) Mortality after parental death in childhood: a nationwide cohort study from three Nordic countries. PLoS Med 11(7):e1001679

Malvaso CG, Delfabbro PH, Day A (2018) Adverse childhood experiences in a South Australian sample of young people in detention. Aust N Z J Criminol https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865818810069

Mccloskey LA, Walker M (2000) Posttraumatic stress in children exposed to family violence and single-event trauma. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39(1):108–115

Melhem NM, Walker M, Moritz G, Brent DA (2008) Antecedents and sequelae of sudden parental death in offspring and surviving caregivers. Arch Pedia Adolesc Med 162(5):403–410

Mok PL, Pedersen CB, Springate D, Astrup A, Kapur N, Antonsen S, Mors O, Webb RT (2016) Parental psychiatric disease and risks of attempted suicide and violent criminal offending in offspring: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry 73(10):1015–1022

Parsons S (2011) Long-term impact of childhood bereavement: prelimary analysis of the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70). Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre. CWRC Working Paper, London

Poole JC, Dobson KS, Pusch D (2017) Childhood adversity and adult depression: the protective role of psychological resilience. Child Abus Negl 64:89–100

Putkonen A, Ryynänen OP, Eronen M, Tiihonen J (2007) Transmission of violent offending and crime across three generations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:94–99

Reed PL, Anthony JC, Breslau N (2007) Incidence of drug problems in young adults exposed to trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: do early life experiences and predispositions matter? Arch Gen Psychiatry 64(12):1435–1442

Rhee SH, Waldman ID (2002) Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: a meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol Bull 128(3):490–529

Rostila M, Berg L, Arat A, Vinnerljung B, Hjern A (2016) Parental death in childhood and self-inflicted injuries in young adults-a national cohort study from Sweden. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25(10):1103–1111

Rostila M, Saarela JM (2011) Time does not heal all wounds: mortality following the death of a parent. J Marriage Fam 73:236–249

Sariaslan A, Larsson H, D’onofrio B, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P (2014) Childhood family income, adolescent violent criminality and substance misuse: quasi-experimental total population study. Br J Psychiatry 205(4):286–290

Sauvola A, Koskinen O, Jokelainen J, Hakko H, Jarvelin MR, Rasanen P (2002) Family type and criminal behaviour of male offspring: the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. Int J Soc Psychiatry 48(2):115–121

Schroeder RD, Osgood AK, Oghia MJ (2010) Family transitions and juvenile delinquency. Socio Inq 80(4):579–604

Serafini G, Muzio C, Piccinini G, Flouri E, Ferrigno G, Pompili M, Girardi P, Amore M (2015) Life adversities and suicidal behavior in young individuals: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24(12):1423–1446

Social Security Administration (2000) Intermediate assumptions of the 2000 trustees report. Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration, Washington, DC

Steeg S, Webb RT, Mok PLH, Pedersen CB, Antonsen S, Carr MJ (2019) Risk of dying unnaturally among people aged 15–35 years who have harmed themselves and inflicted violence on others: a national nested case-control study. Lancet Health 4:e220–e228

Wilcox HC, Kuramoto SJ, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N, Brent DA, Runeson B (2010) Psychiatric morbidity, violent crime, and suicide among children and adolescents exposed to parental death. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(5):514–523. quiz 530

Wilson HW, Berent E, Donenberg GR, Emerson EM, Rodriguez EM, Sandesara A (2013) Trauma history and PTSD symptoms in juvenile offenders on probation. Vict Offender 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2013.835296

Wilson HW, Stover CS, Berkowitz SJ (2009) Research review: the relationship between childhood violence exposure and juvenile antisocial behavior: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50(7):769–779

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm, Sweden (decision no 2014/415-31/5). Personal identification numbers are replaced by random reference numbers before data are made available for research and the researchers did not have access to any personal information that could identify individuals included in study population. Thus, since all data are anonymous, this register-based research does not involve contact with study participants and informed consent is not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berg, L., Rostila, M., Arat, A. et al. Parental death during childhood and violent crime in late adolescence to early adulthood: a Swedish national cohort study. Palgrave Commun 5, 74 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0285-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0285-y

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Single-Parent Families and Adolescent Crime: Unpacking the Role of Parental Separation, Parental Decease, and Being Born to a Single-Parent Family

Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology (2021)