Abstract

Ontological security and the Copenhagen school’s societal security are both concerned with identity. While, the existing literature on ontological security has made use of the Copenhagen school’s concept of securitization, the linkage between societal and ontological security is unclear. Are they different, or does one subsume the other? This article uses the case of majority fears of minority threats to examine the difference between the two concepts. The article shows that the two are distinct—albeit complementary—concepts that explain different things in the security–identity nexus. Securitization theory explains that majorities sometimes designate minorities a threat to their chosen collective identity, while ontological security explains why individual persons—who possess multiple identities—assent to that securitization, including by agreeing to it as audiences, or by requesting it of powerful elites. The article goes on to examine the implications of this ‘ontological–societal security node’ for policymakers and practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This special issue is concerned with examining the dynamics behind ontological insecurity of majorities, this includes attempts to explain why, in multi-ethnic societies, dominant majorities can, and frequently feel threatened, including by immigration, regional integration but also by the forces of globalization (Buzan et al., 9: 121). To examine and explain why dominant groups feel anxious and even threatened by these and other developments, this special edition utilises ontological security as a theoretical framework or lens. Ontological security is about the secure place of an actor, or agent in society, a ‘security-as-being’ (Gustafsson and Krickel-Choi 2020: 877)

For most scholars, central to the concept of ontological security is identity.Footnote 1 Bahar Rumelili argues that: ‘Ontological security is intimately connected with identity, and as such its pursuit requires differentiation and in that sense presupposes an Other.’ (Rumelili, 46: 54) Likewise, Catharina Kinnvall and Jennifer Mitzen, view ontological security as ‘a productive lens for thinking about the relationship between security and identity, and between identity and important outcomes in world politics’ (2017: 3). However, identity is also the pivotal concept of the better-established concept of societal security, which is also sometimes referred to as ‘identity security’ (Wæver, 54: 28). Indeed, scholars working with the theoretical concept of societal security have made the greatest forays into the perceived (in-) security of groups, including majorities (e.g., Huysmans, 27; Karyotis, 30; Bourbeau, 2). Societal security ‘concerns the ability of a society to persist in its essential character under changing conditions and possible or actual threats’ (Wæver, 53: 263).

Scholars less familiar with these concepts will be forgiven ignorance of the putative differences between ontological and societal security, respectively. After all, there may not be any. Browning and Joenniemi (6) lament that with its focus on identity, as opposed to self, ontological security is in danger of collapsing into other theoretical approaches (see also Krickel-Choi, 37). Given the continuous existence of both concepts and their popularity in the literature it is important to establish what, if anything, differentiates them.

Admittedly, some ontological security scholars have sought to identify explicit differences. Bahar Rumelili (46) argues that the two concepts are different for two reasons:

First of all, concerns of ontological security are not limited to a specific referent or sector of security. Certainty and stability of identity remain a concern of states as well as of societies and individuals regardless of whether the threats are located in the cultural or noncultural (military, economic, environmental) realms. Second, societal security remains very much wedded to a survivalist and threat-based conception of security. [As such] societal security refers to the security of a pre-constituted society/identity from harm, threat, and danger. Ontological security does not presuppose a threat to identity but underlines an ongoing concern with its stability.’ (Rumelili, 46: 57).

Rumelili’ s first point does not stand up to scrutiny. First, while it is true that in the societal sector of security the referent object is identity and thus distinct from referent objects in other sectors of security (e.g. sovereignty in the political sector), sectors are not hermetic categories, but instead analytical lenses aimed at simplifying the world (Buzan, et. al, 9: 163–171). In other words, the Copenhagen school recognise that there is interaction between the different sectors of security. Threats to the identity of one group do not simply result from identity security seeking behaviour of other groups, but they can in principle come from any direction. For example, climate change induced melting of the permafrost threatens the identity of indigenous groups in the Arctic, whose culture depends on these specific climate and weather conditions. Likewise, the securitization of identity can create threats in other sectors of security (for example, Brexit leading to a lack of migrant workers threatening the UK economy).

Rumelili’ s second point suggests that societal insecurity is about the situation when survival, or existential threats to identity are present whereas ontological insecurity is about threats below that threshold. It encompasses threats able to simply destabilise, but not undo identities. Meaning that the threshold for threats to identity in the ontological security literature is lower than that set by the Copenhagen school. Rumelili is right about the different thresholds, however, many scholars working with the Copenhagen school’s framework believe that the threshold for threat status in securitization is too high and unrepresentative of political and social practice (e.g. Bourbeau, 3). Consequently, this difference is no longer acute or even present.

Other scholars who invoke both concepts draw a causal relationship between the securitization of identity and ontological in(security). Stuart Croft (10), for example, argues that the securitization of identity by one group, may lead to ontological insecurity of others.Footnote 2 Likewise Rumelili (46: 65) argues that in protracted conflict desecuritization can lead to ontological insecurity because actors’ self-identities are bound up with that conflict. In that sense, securitization produces ontological security. These are important contributions, however, they do not elaborate on the difference between societal (identity) and ontological security. Instead they simply observe a causal relationship between them, specifically to what degree securitization against identity threats (real or perceived) makes or breaks ontological security (as a state of being) (see also Kinvall, 32). My interest in the difference and the relationship between ontological security and societal security goes deeper. From where I stand, it is entirely possible that ontological security has subsumed the older societal security concept/lens, while it is also possible that ontological security has no added value vis-à-vis societal security and other identity related approaches in IR (cf. Browning et al., 6). Either way subsumption would render a distinction between the two concepts meaningless.

As ontological security gains in prominence in scholarship the matter is worth examining further. Moreover, the puzzling case of the dominant group’s insecurity in multi-ethnic societies, which is the focus of this special issue, serves as an ideal case for this research argument. Overall, then, this article is informed by the following research questions:

What, if anything, is the difference between ontological security and societal security vis-a-vis identity? And what does each explain regarding the perceived insecurities of majorities?

To answer these questions, I begin by examining each theoretical concept closely. In brief, I argue that ontological security is primarily about the effects identity has on individuals, specifically who ‘we’ are determines the routines and practices we perform and cherish, as well as our self-perception, and how we narrate our existence. Societal insecurity, in turn, is about threats to a collective identity (a society), and securitization against external or internal threats to societal security an attempt to preserve this collective identity. Given that identity plays a significant role in each, there is thus a deep and immutable connection between perceived threats to societal security and ontological security. Specifically, I argue that a sense of ontological insecurity can explain why individuals assentFootnote 3 to the securitization of identity. I refer to this close relationship between the two as the ‘ontological-societal security node’.

In all of this, it is important to clarify this article’s take on the levels of analysis problem in ontological security studies. In a nutshell this pertains to the question, whether a concept that was originally developed for persons can really be applied to states? (Lebow, 39) And likewise, do states really have feelings and can trust? (Krolikowski, 38)Footnote 4 There are at least two ways out of this conundrum, one is to focus on specific persons (among state elites) as speaking and acting on behalf of states (Vieira, 51), another – which is the line I take here – is to treat collectives needs, fears or views, primarily as the aggregation of individual persons’ views who share one part of their identity, and who have given primacy to that same identity.

The second part of this article goes one step further. It is concerned with the question: What follows from the discovery of the ontological-societal security node for policymakers and practitioners of security? I suggest that the added value of this research findings is that it can help policy makers and elites to address ontological insecurities of the masses. I pursue two quite different lines of argument.

First, given the interconnection between ontological and societal security, I argue that the key to ontological security is a sense of societal security (security here as a state of being, not the practice of securitization (cf. Herington, 25)). I argue that governments etc. who wish to pre-empt or end securitizing requests (securitizing speech acts aimed at convincing more powerful actors/elites to securitize), must – during times of rapid societal change—work to ensure a sense of societal security among majorities. I offer some preliminary thoughts on how this can be done.

Second, taking this in a different direction I argue contra the hitherto established view that securitization is an ethically undesirable tool to achieve ontological security. Browning et al. (6), for instance raise the alarm over studies that emphasise the linkage between ontological security and securitization, because securitization is – in the literature – widely seen as a negative, especially with regards to immigration (see also Rossdale, 45). Kinnvall and Mitzen echo this fear, hoping to ‘in the future [explore] non-securitising dynamics of ontological security seeking in world politics.’ (Kinnvall and Mitzen 2017: 9) I hold against this that the view that securitization is always, or nearly always, morally impermissible is wrong. Yes, securitization harms innocent bystanders, referent subjects and often also referent objects, but on occasion that is proportionate, indeed morally justifiable. It is most certainly the case that securitization is not categorically impermissible simply because minorities are secured against. To make these arguments I draw on Just Securitization Theory (Floyd, 18a and b). In the process I argue that securitization is not only—at times—able to ensure ontological security, but also that the same is not always categorically morally wrong. For policymakers this means that practitioners cannot simply ignore – in their view – undesirable insecurity narratives.

Part 1: the role of identity in ontological security and in societal security

Ontological security and identity

Ontological security has fast moved from being a concept or theoretical lens to a field of study in which distinct notions of ontological security compete. Scholars of ontological security stress different things (for example, on the role and nature of anxiety (Gustafsson and Krickel-Choi, 23, Croft and Vaughan-Williams, 11), and they trace the concepts back to different and often quite distinct thinkers, including Giddens, Heidegger, and Lacan (Seixas- Carvalho, 48). In short, there is not one unified concept of ontological security. To facilitate this research, it is therefore necessary to affiliate this work to one of the ‘schools’ of ontological security. Since, I am not interested in the intricacies of ontological security (e.g., why do routines happen), and since I need a framework that draws out key tenants on which most scholars agree, I align with the Giddensian school.

This move is justified because ontological security owes much to the work of the sociologist Anthony Giddens who – drawing on work by the psychologist R.D. Laing (1960) theorised that persons manage life, specifically dread and anxiety, by adopting a series of routines and narratives about themselves that enable them to cope with the uncertainty of life and their existence (Croft and Vaughan Williams, 11:19). That is, people require a sense of self, to function in society. The ability to function is referred to as ontological security. Here, the concept refers to a ‘person’s fundamental sense of safety in the world and includes a basic trust of other people. Obtaining such trust becomes necessary in order for a person to maintain a sense of psychological well-being and avoid existential anxiety’ (Purnell, 2021: 2, see also Giddens 22: 38–39).

Ontological security entered International Relations (IR) in the late 1990s during the period of widening and deepening security, which saw numerous critical notions of security arise (Huysmans, 26). In 2006 Jennifer Mitzen’s seminal article ‘Ontological security in world politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma’ brought ontological security to wide attention. She argued that states’ care for their ontological security as much as they do for physical security; indeed, their concern with security of self, or else identity, can explain why they sometimes make security related decisions that knowingly undermine their physical security. Mitzen’s article began a cottage industry of research on ontological security. Some scholars – like Mitzen – were happy to talk about the ontological security of states (e.g., Steele, 49, Vieira, 52) raising questions of how a theory originally developed for persons possibly applies here (Lebow, 39 chapter 2). Others avoided this criticism by looking at the ontological security of individual actors (Croft, 10).

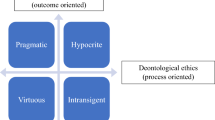

Central to the concept of ontological security is that actors (states or individuals) seek to achieve security of the self via routines. Giddens argues that: ‘The discipline of routine helps to constitute a ‘formed framework’ for existence by cultivating a sense of ‘being’, and its separation from ‘non-being’, which is elemental to ontological security’ (1991:39). In other words, for the Giddensian ontological security scholar, ontological security is indivisibly tied to self-identity (cf. Browning et al., 6), in part because self-identity (who we are, or better how we see ourselves) depends on the performance of routines. Indeed, self-identity ‘has to be routinely created and sustained in the reflexive activities of the individual’Footnote 5 (Giddens, 22:52). Consider the following example: M sees herself as an intellectual (self-identity). On a daily basis, she reaffirms this identity by reading all leading newspaper’s editorials (routine). While, she does this willingly and without the explicit plan of being perceived by others as an intellectual, her actions continuously affirm her self-identification as an intellectual. At the same time – the performance of the routine gives her ontological security (security of being). In short, we can see that the performance of routines is equally crucial to ontological security and to self-identity. Indeed, the workings are quite circular and mutually constitutive see Fig. 1.

Routines (actions and behaviours) are not (entirely) free floating, instead they are determined by how one perceives oneself including vis-à-vis others. Notably, M would not consider herself an intellectual if she merely occasionally read VOGUE. While this would strike most people as intuitively correct, it is unclear why this should be so? I suggest, it is because we collectively know that VOGUE is a fashion journal and that knowledge and/or interest in fashion is – almost by definition – not what it means to be an intellectual. In other words, identities can only be recognised (by self and others) in terms of certain rules and prescriptions. To be X is to behave as Y. We all roughly know what behaviour and narratives would sustain self-identity Y, which is the reason why, when a new(ish) self-identity comes along, we tend to ask what it means to be X, or how it is different to the known K? For example, when pansexuality first came to prominence (e.g., via celebrities such as the US American pop star Miley Cyrus), there was general curiosity regarding how this differs to being bisexual? This is important. Although we speak of self-identity, identities exist between people. To know who one is (not) most of us think in terms of others we are like and those we are unlike from. Moreover, we humans aggregate seemingly similar individuals into groups of people. In other words, each person has a self-identity made up of different identities, but each one of these is likely part of a collective, even if merely disorganised and aggregate group, but certainly one that can be invoked to conjure a sense of belonging (we mothers, us cis-women and so on.) As we shall see, the insight that collective identities are ultimately simply an aggregation of individual identities (Ghosh, 21) (which are also already developed with reference to others) is a vital part in understanding the difference between ontological security and societal security.

Of course, people can voluntarily change their self-identity (they might for example, change their vocation, their sexual identity, their nationality or even their gender). Each change will garner new routines in line with the ‘new’ identity to establish ontological security. While change per se is then not problematic, complications ensue, when an actor perceives a threat to their self-identity, and when they wish to preserve that part of themselves. In short, when change is involuntary. In this context it is important to note that each person’s self-identity is unlikely to be singular. Speaking of myself, for example, I am—at a minimum—a cisgender women, a mother, an academic, German born but I self-identify more readily with my chosen home of Britain. Strictly speaking then, we ought to speak not of a real or perceived threat to one’s identity, but to one of the many identities that make up a person’s self-identity.

It is also the case, however, that threat perception to a part of one’s self-identity elevates that identity above other parts. Wæver argues as follows: ‘People basically live with multiple identities and these do not necessarily have a clear or permanent hierarchy in relation to each other. But in specific situations, especially the closer one comes to war in either literal or metaphorical forms, the more there will be a hierarchy’ (1997: 262). See also, Kinnvall, who argues that ‘This invariably entails a process of establishing and confirming certain identity-traits in yourself and the juxtaposition of these to others’ (2007: 35, see also Wæver, 53: 262). Indeed, in this context Kinnvall speaks of ‘the preoccupation with one true identity’ which she refers to as the ‘securitization of subjectivity’ (ibid:27). In other words, when actors feel that their primary identity is threatened, they become willing to engage in – at a minimum – securitizing language, which in turn can cause a sense of security or of insecurity in others (cf. Croft, 10).

Kinnvall’s intervention nicely shows what securitization theory adds to ontological security studies. Ontological security refers to the condition of being secure not to the practice of security (securitization).Footnote 6 Put differently, ontological security is the absence of anxiety and dread, achieved through routines, trust and stable self-narratives, securitization is the defence against threats (real or perceived). In normal times ontological security is achieved via mundane routines that have nothing to do with the extraordinary measures associated with security practice (securitization). To be sure, some people like Rumelili (46) have shown how securitization can shore up identity and hence ontological security. My point is that without the substantive theoretical concepts advanced by securitization theory (including speech act, the referent object etc.) it is difficult to operationalise the link between ontological (in-)security (a state of being) and a specific kind of action (here security practice).Footnote 7 Kinnvall’s study, in turn shows that ontological (in-)security can motivate individual actors to engage in securitization. Other scholars confirm this. Christopher Browning, who has moved from securitization studies into ontological security studies, for instance, argues that securitization of (read against) ‘threatening others’ can be seen as a manifestation into concrete fear of hitherto diverse anxieties (Browning, 5: 225–226). In other words, securitization is one form of ontological-security seeking behaviour.

While there is then a link between ontological security and securitization, it remains unclear how the Copenhagen school’s concept of societal or identity security differs from ontological security. This is reflected in the literature, where there is confusion on what causes what and how the two relate. Croft, for example, argues: ‘[…] the securitization of identities is a crucial issue for the understanding of ontological security. The securitization of identity leads to the securitization of subjectivity […]’ (2012:73, my emphasis). While, to repeat an argument from above, Kinnvall argues that an increase in ontological insecurity leads to attempts to ‘securitize subjectivity’ (Kinnvall, 749). It is this issue of difference or sameness I will now turn to. First though what is societal security?

Societal security and identity

Societal security originates in Barry Buzan’s People, States and Fear (1983 and 1991) in which Buzan identifies a range of different threats to the state he divides into sectors of security: military, political, economic, and so on. One such type are societal threats, which are threats to the identity and cohesion of the state, most from below (Buzan, 7: 122–123). In Security: A new Framework for analysis (1998) we encounter again Buzan’s security sectors. In line with the widening and deepening of security (in practice and theory), here the state is no longer the only referent object of security. Consequently, societal security is now not merely about threats to the state but to actors and entities at all possible levels of analysis, bar individuals. Indeed, the referent object of securitization in the societal sector of security is identity, not as previously assumed by Buzan sovereignty (Buzan et al., 9: 119). Securitization here refers to the ‘move that takes politics beyond the established rules of the game and frames the issue either as a special kind of politics or as above politics’ (Buzan et al., 9: 23). Securitization usually takes the form of a speech act, the securitizing move, which sees the securitizing actor declare X is existentially threatened, consequently that recourse to extraordinary measures is now a necessity (including by specifying a point of no return). Lots of securitizing speech act exist, however, the most interesting ones are those that give way to extraordinary measures to secure the referent object. Extraordinary, hereby, signifies a breaking with ordinary conduct for the actor in question. For example, lock-down to address the Covid-19 virus disease.

In the chapter on societal security, the Copenhagen school highlight migration (read immigration) ‘X people are being overrun or diluted by influxes of Y people; the X community will not be what it used to be, because others will make up the population’ [….] Horizontal competition' due to the pull of other bigger identities (Americanisation or Globalisation) and vertical competition, the situation when people ‘stop seeing themselves as X’ due to integration or secession, and depopulation as the primary drivers of societal or identity insecurity, giving impetus to societal securitization (Buzan et al., 9: 121). While this was and remains ground-breaking work, it is also the case that the Copenhagen school and many of their followers, do not adequately distinguish between the securitizing actor and other actors in the securitization process. Notably, should actors that ‘merely’ declare someone or something existentially threatened, without the intention to seek approval from a putative audience for the use of extraordinary measures, but instead with a view to convincing a better placed and more powerful actor to securitize the issue, really be called securitizing actor? In my view, a lot is lost if we do not differentiate between – at a minimum – securitizing actors and functional actors, a securitizing actor is the actor that would utter the securitizing move (declare an existential threat to an identity) and – because successful securitization includes extraordinary measures – carry out extraordinary measures or instruct those they are in a position of power over to do the same. A securitizing requester in turn is ‘merely’ someone who seeks to convince a more powerful actor of the need to securitise by painting a picture of the threat situation. Finally, a functional actor is an actor that vetoes or endorses securitization on behalf of others’ (Floyd, 19: 88).

In addition, the Copenhagen school suffers from at least one other weakness: a form of state-centrism. Not state-centrism in the conventional sense of focusing only on the state as a referent object,Footnote 8 but in the sense that they consider only identities large enough to rival the state as viable referent objects of securitization in the societal sector (Wæver, 53:263).Footnote 9 Since, the Copenhagen school and Wæver’s early publications the world has changed. The politics of identity has led to a veritable multiplication of identities many of which are amplified and sustained by social media usage. Based on this, I would suggest that identities need no longer be large enough to rival the state for primacy to count for referent objects of securitization.

The value of the Copenhagen school’s securitization theory is that they have enabled us to understand that a threat to identity, just as likely as physical insecurity, can motivate securitization. Wæver writes as follows: ‘Suddenly the collective stands above the individual, or rather, one assumes that one’s own worth, destiny and meaning of life depends on the fate of the collective, the whole to which one belongs’ (Wæver, 53: 274) And yet, the Copenhagen school does not discuss why individuals get involved. Put differently, they do not tell us why the collective suddenly ‘stands above the individual’ only that it does. There are at least two reasons why the Copenhagen school does not elaborate on the reasons individuals may hold. First, they are agnostic on the ‘why do actors securitize’ question. Insofar as they provide an answer; it is simply read off from what the actors themselves say. The reasons for this lie in Wæver’s postmodernist leanings, which mean that one cannot peep beyond the text and get at the hidden motives of actors (Floyd, 16: 23–31).

Second, the Copenhagen School has little interest in the individual as either referent object or securitizing actor. Securitization theory is set up in such a way (namely as an intersubjective process) that it practically excludes a focus on the individual. Moreover, societal insecurity, in turn, is about threats to a collective identity (a society), and securitization against external or internal threats to societal security an attempt to preserve this collective identity (it is never about the individual) (cf. Wæver, 53: chapter 8).

Picking up the themes introduced above, I want to suggest that ontological security can complete the puzzle by offering a viable answer to the question: why do individuals assent to the securitization against identity concerns? It enables us to see the following: A threat (real or perceived) to a collective identity (say, Britishness) due to high levels of immigration does not only affect the collective (which might disintegrate, dilute, or even cease to exist in its current form), but it threatens to also have acute effects on individuals’ self-identity. With Britishness, as with any other identity, comes a set of routines and narratives, pivotal for individuals who self-identify as British. Ergo a loss of, or a substantial reduction of those routines would lead to ontological insecurity, or else feelings of dread and anxiety. To put it simply, the self is threatened when routines are threatened, and routines are threatened when identity is threatened. The fear of the loss of ontological security motivates individuals to engage with the securitization against identity issues, either as audiences or as securitizing requesters and, where there is no higher protector to appeal to, even as securitizing actors.Footnote 10 Securitization studies tells us that these actors are likely to succeed (either in securitizing or in persuading others to securitize) only if they can appeal to a sufficiently large group of people, addendum whose individual members also give primacy to (in our case) Britishness.

If then this link between societal securitization and ontological security can explain why individuals join into securitization (this, as we have seen, can take multiple forms), what logic explains individuals’ assent to securitization in the other sectors of security? Specifically, in cases of securitization that have nothing to do with identity and therefore do not infringe an individual’s ontological security, what motivates individuals to engage with securitization? The answer is simple, in such cases individuals are motivated by fears of physical harm. Covid-19, for example, did not pose a threat to ontological security (admittedly the securitization against Covid-19 did for a while), in such cases individuals assented to securitization because it posed an existential threat—real or perceived—to people. My broader claim thus is that individuals agree to or request securitization when they can link the threat to their own lives or to that of their nearest and dearest. In cases where there is no physical danger (or dying, disease and disability), a perceived or real threat to ontological security can provide that rationale.

In particular, seeing that functional actors are not necessarily directly affected by securitization; all this raises the question what explains these actors’ assent to securitization? Why, for instance, do individuals sometimes rebel – on behalf of strangers- against securitization. Here is not the place to offer a fully-fledged answer to this question. I suspect, however, that emotion and feelings of empathy for likeminded people play a role. In short, functional actors’ assent to securitization when they feel an emotional connection between their situation and referent objects or securitization subjects.

To summarise the argument so far, we can now see that while both ontological security and societal security are about identity, they are not the same thing. The concept of societal security enables us to see that – at times – identity is the referent object of securitization, which is to say that rhetoric and relevant securitizing actions are tailored towards a perceived or real existential threat to an identity. Ontological security, in turn, is about an individual’s sense of self in the world (a feeling of safety and a sense of being carefree). To achieve this, individuals (and arguably states) carry out routines that are determined by how they perceive themselves (their identity), but that also serve to reaffirm an individual’s identity. A threat to a primary identity thus negatively affects ontological security, and in turn drives individuals to assent to securitization. Let us call this relationship the ‘ontological-societal security node’.

Before looking at some of the practical implications of the research argument here developed, I want to make a few things clear. First, although there is a deep connection between ontological security and societal security, individuals within stable societies are not necessarily ontologically secure. After all, every individual has multiple identities, and any one of these may be perceived threatened. This much is evidenced by the persistent identitarian conflicts in the ongoing culture wars (Duffy and Hewlett, 2021). Moreover, the securitization of identity, does not necessarily generate ontological security, after all – in some cases – ontological security is unachievable because it rests on fantastical imaginaries (Kinnvall, 33; Eberle, 14).

Second, it is important to understand that while all societies have the potential to fall prey to the ‘ontological-societal security node’, not all of them will. In some societies a level of change through, for instance, continued migration is a part of that society’s identity. Canada, for example, is built on a culture of immigration and societal change whereas Japan is not. Put differently, in distinct societies different triggers of ontological insecurity prevail (cf. von Essen and Danielson, 2023).

Part two: policy and practical implications

Academic work can have two kinds of value. First, does it usefully advance our knowledge of empirics or theory? And second, can it usefully guide the behaviour of relevant actors and ultimately improve the world? Clarification on the ontological-societal security node ticks the advancement of knowledge box, the second part of this research article is concerned with discussing this research’s action-guiding potential. I pursue two different kinds of argument. First, I consider what governments and other actors ought to do if they wish to reduce securitization against minority identities by majority groups. Second, I suggest that the securitization against identity threats (including by localised majorities) can be morally justifiable, and I consider what this means for the state.

How to avoid the securitization against identity concerns?

The rise of national populism is a major concern for members of the liberal elites of many Western states. Standard responses to this rise by liberal elites usually involve the declaration of sympathisers as inter alia xenophobic, bigoted, racist, and even stupid. In Britain, this logic was never more apparent than after the Brexit referendum, when leave-voters where regularly called “‘thick, ignorant, racist’ or ‘stupid’” (Patel and Connelly, 43: 976, see also Browning, 5: 344) including by politicians. This is not a paper about Brexit, I merely use this example to call out the rhetorical weapons of choice for those who disagree with national populism. From the sweltering culture wars and the partisan divide in the contemporary United States (US), however, we already know that name calling, and public derision leads to one thing only: even greater divisions. I do not think that any society in Europe wants to go down that route, while many people within the US surely must want to come back from the brink. I wish to suggest, that the research findings offer some insight on how European countries can avoid slipping further into the abyss of culture wars and the securitization against foreign identities by right wing parties and groups.

The ‘ontological-societal security node’ suggests that pivotal to a person’s ontological security is a sense of societal security. The point of connection between the two concepts is identity. Identity is the referent object of a societal securitization, which is to say, identity is the thing to be secured including by recourse to extraordinary measures (were sub-state groups of people are concerned this includes vigilantism). Likewise, identity is the thing that determines routines and narratives essential to a person’s sense of self (their ontological security). A threat – even a perceived threat to identity thus motivates people to speak up and to act to safeguard that identity. This means that if governments, international organisations, think tanks, universities and such-like, wish to end certain kinds of securitizing requests (securitizing speech acts aimed at convincing more powerful actors/elites to securitize), and/or to pre-empt securitizing moves and/or audience acceptance of such moves, they must – during times of rapid societal change – work to ensure that there prevails a real sense of societal security among majorities. But what would this entail? According to the Copenhagen school, societal security is ‘the ability of a society to persist in its essential character under changing conditions and possible or actual threats’ (Wæver, 53: 263). The essential character of a state pertains – at a minimum – to a shared language (sometimes languages), culture, tradition, and history. It is beside the point that high levels of immigration, globalisation or regional integration may not really (objectively) threaten any of these things. What matters is that even majorities – and securitization scholars have amply shown this – often believe and feel that their national identity is threatened by these forces. If this is so, how can (assent to) securitization of national identity be pre-empted? I suggest that what matters is that state leadership and elites – often (rightly or wrongly) in favour of the feared changes acknowledge and openly address the fears of the general population. This is precisely what they don’t do. Research on the rise of populism has shown that the feeling of being ignored by elites is a major factor in the rise of such parties (See multiple in Kaltwasser et al., 29). Roderick Hart, for example, identifies this a major factor in Trump’s otherwise hard to explain victory.

Given Trump’s reveries and his kill-or-be-killed mentality, his election is all the more surprising. But elected he was and that, I believe, shows the danger of letting people feel ignored. Despite her gold-plated resumé and unquestionable sense of duty, many felt forgotten by Hillary Clinton and her establishment coterie. Donald Trump ignored nobody. He attacked his opponents vigorously and he embraced his supporters vigorously. Bizarre though he was, many could not resist him (Hart, 24:36).

Regarding Germany’s rise of the AFD (Alternative for Germany) party, Julia Schulte-Cloos, has shown that the party did not arise solely in response to multiple crises, but rather tapped into ‘latent [...] deep-seated nativist sentiments’, present in much of Germany, but ignored by mainstream parties (2022: 1). In Germany the situation is further amplified by a widespread stigmatization as Nazi, if one so much as questions the possible negative effects on social cohesion of high levels of immigration (Bergk, 1). Of course, mainstream politicians themselves are not immune to being labelled as such, which means that they are likely to ignore such voices, driving those ignored, or indeed labelled as right wingers further towards populist parties.

The solution rests in a two-pronged strategy. First, practice open dialogue, ensure freedom of speech and tolerance for the views of others (cf. Floyd, 17). Importantly, in open dialogue both sides can still voice their concerns in stark terms, this is important because, doing this is a form of routinized behaviour instrumental to their ontological security. Second, open dialogue risks worsening the problem, if the same is not accompanied by policy initiatives and social structures that ensure that people are not left behind. Studies from, for example, East Germany show that those with the lowest income are most likely to hold right wing views (Decker, et. al, 12:12). This puts onus on national governments to encourage—in contemporary UK government speech—levelling-up’, but it also shows the importance of publicizing such efforts and success stories.

On the possibility of just and unjust securitization against identity threats

My second argument goes further, I want to consider the possibility that the securitization against identity threats, which would ensure the ontological security of some, is not categorically a bad thing. Indeed, the same can be morally permissible, and at times even morally required. It is fair to say that in the relevant literature (securitization studies and ontological security studies) very few scholars would consider securitization and identity through this lens. Indeed, the widely shared view that securitization is mostly a negative thing, something to be avoided in favour of desecuritization (broadly political solutions), is tightly bound up with unease over the securitization against identity issues by some actors (the EU, Trump etc.). In the EU, securitization has allowed the drowning of migrants in the Mediterranean (Alkopher, 13). Moreover, the language-focused security scholars’ inadvertent role in the social construction of this reality places additional need to speak up in favour of desecuritization (Huysmans, 28; Taureck, 50). It is therefore no surprise that security scholars take a dim view of securitization against identity concerns as an ontological security seeking tool (cf. Browning et al., 6, see also Lerner, 40). In this context, Maria Mälksoo (41) makes a noteworthy point. She argues, not only that the rationale of ontological security problematically justifies the securitization of (read: against) identity, but also that this logic makes securitization inevitable. In what follows I want to take on some of these points. To do this, I draw liberally on Just Securitization theory (Floyd, 2019) that develops criteria when securitization is morally permissible, by drawing on the Just war theory.

I want to begin my challenge of the orthodoxy by suggesting that it does not do to dismiss the fears of majorities as unwarranted simply because they are, well, in the majority. Majority status is, after all, a matter of perspective. Viewed from a global perspective localised majorities (e.g., in their respective countries, indigenous Germans, Swedes, or Danes) are globally scarce, hence minorities. Consequently, we can no longer say that ‘majorities’ are always in a position of strength and hence secure. Indeed, localised majorities are no less entitled to being worried that their respective primary identities are threatened when faced with rapid change (notably, but not exclusively, by high levels of immigration) to their societies. After all, globally there is only one Denmark, Sweden, and Germany and so on! While such an intersubjective fear may give rise to securitization, it does not automatically justify recourse to securitization (cf. below). However, neither is it the case that securitization against threats to identity can never be morally justified. Elsewhere I have (Floyd 18) shown that securitization is morally permissible if there is a real and existential threat to a referent object that is morally valuable, that the securitizing actor is sincere in their intentions, that securitization is a proportionate response to the threat, and that securitization has a better chance of achieving the just cause than other less harmful options (notably politicisation). While these thresholds are high, we can see that it is in principle possible that the securitization against identity threats, including against minority groups could be morally permissible.

Assuming, for the sake of argument, that this is correct, what are the implications from this for the policymaking world and practitioners? One implication of this is that policymakers and elites cannot simply dismiss calls for the securitization against identity threats made by individuals who fear for their ontological security as morally wrong, ill-informed, ignorant, and dangerous. Instead, they should evaluate claims regarding the threat level carefully and objectively, and if necessary, act on the issue. Acting here does not mean securitization, it merely means that relevant political action is taken to ensure the societal security of people. This is especially important for elites ideologically opposed to the securitization against identity threats, who would not wish to let things deteriorate to the point where securitization is the best option.

The importance of acting is crucial for a second reason. Notably, if governments fail to act on an objective existential threat to its people (or parts thereof) the social contract that otherwise binds people and their government is annulled, giving non-state actors permission to securitize (Floyd, 20, 18: 146–7. See also Fabre, 15: 148 and Wolfendale, 55: 261). Any state leadership must have an interest in preventing that eventuality. I suggest that the way to prevent this is to take ontological and societal security seriously.

It is important to note that although this article allows room for the just securitization of identity, the argument does not rest on the view that ontological security (i.e. the condition of having a stable sense of self) is objectively valuable.Footnote 11 Just securitization theory specifies that only referent objects that meet basic human needs (specifically autonomy and physical), and that ‘respect the needs of outsiders’ are morally justifiable and eligible for self or other defence via securitization (Floyd, 18: 100). This is based on the ‘humanistic principle’ which holds that a thing’s value rests on its ‘contribution, actual or possible, to human life and its quality’ (Raz 44: 194). Concretely this means that the moral value of any given ontological security is only as valuable as is the identity/self it refers to. The Hindutva movement in contemporary India, for instance, is valueless (read: immoral), because it is built on intentionally infringing other people’s (here Muslims) basic human needs (cf. Kinnvall, 33).

Conclusion

As part of this special edition this article is concerned with explaining the puzzle why majorities sometimes feel threatened by minority groups. In line with the brief provided by its editors, I have in this research focused on ontological security to answer this question. Throwing the analytical net wide, however, I have suggested that the case study is an opportunity to examine the putative differences between on the one hand ontological security, and the Copenhagen school’s societal security on the other. This was justified because both concepts focus on identity, and for the unversed it is not always clear what these two distinct theoretical concepts bring to the table that is not already covered by the other concept. In particular, once we realise that ontological security speaks to individuals and states and that societal security (albeit under the label identity security) does too.

This research has shown that while both concepts are about identity, they inhabit different spaces in the security equation. In a nutshell, securitization and societal security explain that relevant actors construct identity as a threat, while ontological security can explain why individual persons, who have multiple identities, assent to securitization. Assent here is meant to capture that individuals can fulfil different functions in the securitization process, in this context most notably audience, securitization requester and functional actor (Floyd, 19). Ontological security and societal security are as such distinct but complementary concepts. This is an important finding; it can end or forestall possible claims of analytical superiority among securitization scholars and ontological security scholars. Moreover, although much work has been done on the audience in securitization, this work usually focuses on who the audience is, or on the contextual factors that make securitization likely, not so much on why audiences’ consent to securitization. As such this article is a significant contribution to securitization studies. Beyond this, its findings are also important for ontological security studies. Out of a whole range of security theories, ontological security uniquely can explain what – beyond physical needs – motivates individuals’ decision to fight figuratively or literally.

Second, the research disputed the in the literature standard view that ontological security seeking via securitization is necessarily a negative development. By invoking Just Securitization Theory (Floyd, 18, 20) I argued that the picture is much more nuanced. The securitization of identity can be morally justifiable, provided there is a real threat, that the referent object is morally justifiable and so on. The article also considers the implications of the research argument for the policymaking world. In ontological security studies this is not always a feature of research papers, many of which can be highly specialised and theoretically dense. By contrast, this research shows that the concept of ontological security is important for policymakers and practitioners. Although I discuss with (1) how to pre-empt securitization and (2) just securitization, two quite distinct issues, the discussion converges on the same message. Namely, take ontological security as seriously as physical security, not only for the sake and well-being of the people living in the state, but also for the well-being of state (notably a failure to act on ontological security concerns can result in a justified backlash). The overall message being that while securitization against identity threats may sometimes be morally permissible, pre-emption of insecurity giving rise to securitization, is still a better option.

While ontological security may seem an alien concept for policymakers, in the United Kingdom at least it chimes with the government’s new mental health agenda that promises to elevate mental ill-health the same status as physical ill-health. This means that now is an opportune time to raise the profile of ontological security with relevant policymakers.

Notes

While identity has been identified as a central component of ontological security in the IR literature it is not the only component, existence and continuity across space and time are other elements (cf. Krickel-Choi, 37).

In securitization studies it is common to speak of the securitization of X, whereby X refers to the threat. For example, the securitization of climate change, or the securitization of terrorism. Confusingly, in the context of identity and securitization the X can also refer to the referent object. That is, the securitization of identity can also mean the save-making of the referent object (here identity) via securitization. To avoid this confusion, I–in this article–deviate from what is customary. Given that securitization is a form of self- or other-defence I speak of the securitization against identity, in cases where identity issues are threats, whereas when I speak of the securitization of identity, the latter is the referent object.

I use assent to mean not only passively agree with securitization as audiences, but also to actively request securitization.

The fact that states are subjects in ontological security studies also means that the substantive difference between ontological and societal security cannot simply rest with the same issue (identity), albeit at different levels of analysis.

Self-identities can change, actors have agency over this happening.

The relationship is akin to that between money and borrowing. Money is a thing, borrowing one way to achieve the thing, but one that is also risky and that can go wrong.

Note here, I am not claiming that ontological insecurity always leads to securitization (cf. Krickel-Choi, 35b).

This is an oft repeated claim, alas it is one that has always been untrue (see, for example, Buzan and Wæver, 8: 71.

This publication is representative of the Copenhagen school, as it is the same as chapter 2 in the co-authored Identity, Migration and the new Security Agenda in Europe (1993).

This observation is shared (at least partially) by Kaunert and Ezeokafor who in a paper on ontological securitization of health in Africa argue that: ‘Why do we need the insights from the ontological security literature within the securitisation framework? The answer is simple—the securitisation framework on its own does not provide a clear answer to the ‘why’ of the securitisation, nor does it analyse the dynamics of securitisation to any significant extent’ (2022:3). To be sure, however, Kaunert et al., focus on state as the level of analysis not individuals.

Needless to say, it will be subjectively valuable to the ontological security seeker.

References

Berg, S. (2018) Die Nazibeschimpfung, Cicero https://www.cicero.de/kultur/deutsche-geschichte-nazi-beschimpfung-68er-deutschland-seehofer

Bourbeau, P. 2011. The securitization of migration: A study of movement and order. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

Bourbeau, P. 2014. Moving forward together: Logics of the securitisation process. Millennium 43 (1): 187–206.

Browning, C.S. 2018. Brexit, existential anxiety and ontological (in) security. European Security 27 (3): 336–355.

Browning, C.S. 2019. Brexit populism and fantasies of fulfilment. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32 (3): 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1567461.

Browning, C.S., and P. Joenniemi. 2017. Ontological security, self-articulation and the securitization of identity. Cooperation and Conflict 52 (1): 31–47.

Buzan, B. (1991). People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Buzan, B., and O. Wæver. 2003. Regions and powers: The structure of international security, 71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buzan, B., O. Wæver, O. Wæver, and J. De Wilde. 1998. Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Croft, S. 2012. Securitizing Islam: Identity and the search for security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Croft, S., and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2017. Fit for purpose? Fitting ontological security studies ‘into’ the discipline of international relations: Towards a vernacular turn. Cooperation and Conflict 52 (1): 12–30.

Decker, O., J. Kiess, and E. Braehler. 2023. Autoritaere Dynamiken und die Unzufriedenheit mit der Demokratie Die Rechtsextreme Einstellung in den neuen Bundeslaendern. EFPI Policy Paper: University of Leipzig.

Dingott Alkopher, T. 2024. Securitisation in the Mediterranean: An ethical analysis of the EUNAVFOR MED SOPHIA operation using the prism of Floyd’s Just Securitisation Theory (JST). European Security 33 (2): 303–323.

Eberle, Jakub. 2018. Desire as geopolitics: Reading the glass room as central European fantasy. International Political Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/oly002.

Fabre, C. 2012. Cosmopolitan war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Floyd, R. 2010. Security and the environment: Securitisation theory and US environmental security policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Floyd, R. 2018. Parallels with the hate speech debate: The pros and cons of criminalising harmful securitising requests. Review of International Studies 44 (1): 43–63.

Floyd, R. 2019. The morality of security: A theory of just securitization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Floyd, R. 2021. Securitisation and the function of functional actors. Critical Studies on Security 9 (2): 81–97.

Floyd, R. 2024. The duty to secure: From just to mandatory securitization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ghosh, R. (2023) ‘Education, identity and diversity’, In Editor(s): Robert J Tierney, Fazal Rizvi, Kadriye Ercikan, International Encyclopaedia of Education (Fourth Edition), Elsevier, Pages 83–92,

Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. California, USA: Stanford University Press.

Gustafsson, K., and N.C. Krickel-Choi. 2020. Returning to the roots of ontological security: Insights from the existentialist anxiety literature. European Journal of International Relations 26 (3): 875–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120927073

Hart, R.P. 2020. Trump and us: What he says and why people listen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Herington, J. (2015). Philosophy: The concepts of security, fear, liberty, and the state. Security: Dialogue across disciplines, 22–44.

Huysmans, J. 1998. Security! What do you mean? From concept to thick signifier. European Journal of International Relations 4 (2): 226–255.

Huysmans, J. 2000. The European Union and the securitization of migration. JCMS Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (5): 751–777.

Huysmans, J. 2006. The politics of insecurity: Fear, migration and asylum in the EU. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kaltwasser, C.R., P.A. Taggart, P.O. Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, eds. 2017. The Oxford handbook of populism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Karyotis, G. 2012. Securitization of migration in Greece: Process, motives, and implications. International Political Sociology 6 (4): 390–408.

Kaunert, C., and E. Ezeokafor. 2022. Ontological securitization of health in Africa: The HIV/AIDS, Ebola and COVID-19 pandemics and the foreign virus. Social Sciences 11: 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080352.

Kinnvall, C. 2007. Globalization and religious nationalism in India: The search for ontological security, vol. 46. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kinnvall, C. 2019. Populism, ontological insecurity and Hindutva: Modi and the masculinization of Indian politics. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32 (3): 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1588851.

Kinnvall, C., and J. Mitzen. 2017. An introduction to the special issue: Ontological securities in world politics. Cooperation and Conflict 52 (1): 3–11.

Krickel-Choi, N.C. 2022. The embodied state: Why and how physical security matters for ontological security. Journal of International Relations and Development 25: 159–181.

Krickel-Choi, N.C. 2022b. The concept of anxiety in ontological security studies. International Studies Review 24 (3): viac013.

Krickel-Choi, N.C. 2024. State personhood and ontological security as a framework of existence: Moving beyond identity, discovering sovereignty. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 37 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2022.2108761.

Krolikowski, A. 2008. State personhood in ontological security theories of international relations and chinese nationalism: A sceptical view. Chinese Journal of International Politics 2 (1): 109–133.

Lebow, Richard N. 2016. National Identities and International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lerner, A. B. (2023). Global injustice and the production of ontological insecurity. European Journal of International Relations, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661231219087

Mälksoo, M. 2015. ‘Memory must be defended’: Beyond the politics of mnemonical security. Security Dialogue 46 (3): 221–237.

Mitzen, J. 2006. Ontological security in world politics: State identity and the security dilemma. European Journal of International Relations 12 (3): 341–370.

Patel, T.G., and L. Connelly. 2019. ‘Post-race’ racisms in the narratives of ‘Brexit’ voters. The Sociological Review 67 (5): 968–984.

Purnell, K. 2021. Bodies coming apart and bodies becoming parts: Widening, deepening, and embodying ontological (In)Security in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Studies Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1093/isagsq/ksab037

Raz, J. 2019. The morality of freedom. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Rossdale, Chris. 2015. Enclosing critique: The limits of ontological security. International Political Sociology 9 (4): 369–386.

Rumelili, B. 2015. Identity and desecuritisation: The pitfalls of conflating ontological and physical security. Journal of International Relations and Development 18: 52–74.

Schulte-Cloos, J. 2022. Political potentials, deep-seated nativism and the success of the German AfD. Frontiers in Political Science 3: 698085. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.698085.

Seixas -Carvalho, B. 2023. The psychic dimensions of foreign policy: ontological security, emotions, and fantasy, Unpublished prospective PhD thesis chapter University of Birmingham

Steele, B.J. 2008. Ontological security in international relations: Self-identity and the IR state. Abingdon: Routledge.

Taureck, R. 2006. Securitization theory and securitization studies. Journal of International relations and Development, 9(1).

Vieira, M.A. 2016. Understanding resilience in international relations: The non-aligned movement and ontological security. International Studies Review 18 (2): 290–311.

Vieira, M.A. 2018. (Re-) imagining the ‘self’of ontological security: The case of Brazil’s ambivalent postcolonial subjectivity. Millennium 46 (2): 142–164.

Wæver, O. 1997. Concepts of security. Institute of Political Science: University of Copenhagen.

Wæver, O. (2003) ‘Securitisation: Taking stock of a Research Programme in Security Studies’, unpublished manuscript.

Wolfendale, J. 2017. Defining War. In Soft War: The Ethics of Unarmed Conflict, ed. Michael L. Gross and Tamar Meisels, 16–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Floyd, R. Ontological vs. societal security: same difference or distinct concepts?. Int Polit (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-024-00581-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-024-00581-w