Abstract

In moments of international crisis, US presidents have historically rallied public support by evoking the national identity. Affective polarization undermines the salience of national identities and threatens to carry domestic divisions across the water’s edge. Does affective polarization reduce individuals’ support for military action? When is polarization most likely to extend beyond the water’s edge? I argue that the foreign policy consequences of affective polarization vary across intervention contexts and individuals. Using a series of ten survey experiments conducted during the 2016 presidential election season, I investigate the presence and stability of partisan gaps in support across security and humanitarian interventions. A second survey experiment directly manipulates negative partisanship, the president’s party affiliation, and the intervention scenario. The results indicate that negative partisanship can undermine the president’s ability to generate support for intervention, but context matters. Humanitarian interventions provide some insulation from the effects of affective polarization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See appendix for the details of each experiment and the survey instruments.

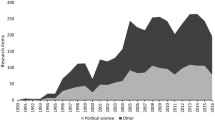

These data are limited to the period prior to (and on the day of) the election because poll questions gauging candidate and party favorability become scarce after the election is decided.

Included polls are from: May 16–19, 2016 (The Washington Post/ABC News, 2016), June 15–26, 2016 (Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 2016b), July 8–12, 2016 (New York Times/CBS News, 2016), August 9–16, 2016 (Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 2016a), September 1–27, 2016 (PRRI, 2016), October 20–25, 2016 (Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, 2016c), November 8, 2016 (National Election Pool (ABC News, Associated Press, CBS, CNN, Fox News, NBC), 2016).

Dynata employs matching to approximate a nationally representative sample. In addition to standard demographics, this sample also matched national levels on party identification, gender, age, and education. Due to financial constraints, experiment two assigned approximately 400 respondents to the terror conditions and just over 200 respondents to the humanitarian conditions. The sample size contributes to the larger confidence intervals surrounding the humanitarian intervention estimates, but does not obscure the magnitude of the effects. The results from the humanitarian intervention scenario are also consistent with pretests with a larger sample, reported in appendix.

The bandwidth for plots in Fig. 1 is 0.80, but the trends remain consistent across alternative specifications.

Based on a logistic regression model specified as: Pr(Ysupport = 1) = logit−1(β0 + β1XHighPartisanship + β2ZHumanitarianIntervention + β3XHighPartisanshipZHumanitarianIntervention), where logit−1 is the inverse logistic link function. Full results and marginal effects are included in the appendix.

Based on a logistic regression model specified as: Pr(Ysupport = 1) = logit−1(β0 + β1XHighPartisanship + β2ZDemocrat + β3XHighPartisanshipZDemocrat), where logit−1 is the inverse logistic link function. There is no evidence that the party of the president or copartisanship with the president significantly moderate the effects of the high partisanship treatment.

Based on the same logistic regression model specified in endnote 6, limiting the sample to only Democrats.

References

Abramowitz, A.I. 2010. The Disappearing Center. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Abramowitz, A.I., and K.L. Saunders. 2008. Is Polarization a Myth? The Journal of Politics 70 (2): 542–555.

Albertson, B., and S. Kushner Gadarian. 2015. Anxious Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Aldrich, J.H., J.L. Sullivan, and E. Borgida. 1989. Foreign affairs and issue voting. American Political Science Review 83 (1): 123–141.

Aldrich, J.H., et al. 2006. Foreign policy and the electoral connection. Annual Review of Political Science 9 (1): 477–502.

Baum, M., and T. Groeling. 2010. Reality asserts itself: public opinion on iraq and the elasticity of reality. International Organization 64: 443–479.

Berinsky, A. 2007. Assuming the costs of war. Journal of Politics 69 (4): 975–997.

Boettcher, W. 2004. Military intervention decisions regarding humanitarian crises. Journal of Conflict Resolution 48 (3): 331–355.

Brody, R. 1991. Assessing the President. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Brutger, R. (2020) ‘The Power of Compromise: Proposal Power, Partisanship, and Public Support in International Bargaining’. World Politics 73 (1): 128–166.

Bryan, J. and Tama, J. (2020) ‘The Prevalence of Bipartisanship in US Foreign Policy: An Analysis of Important Congressional Votes’. Workshop on Domestic Polarization and US Foreign Policy: Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Implications.

Canes-Wrone, B., W.G. Howell, and D.E. Lewis. 2008. Toward a broader understanding of presidential power. Journal of Politics 70 (1): 1–16.

Evers, M.M., A. Fisher, and S.D. Schaaf. 2019. Is there a trump effect? an experiment on political polarization and audience costs. Perspectives on Politics 17 (2): 433–452.

Finnemore, M. 2003. The Purpose of Intervention. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Fiorina, M.P., and S.J. Abrams. 2008. Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science 11 (1): 563–588.

Fiorina, M.P., Abrams, S.J. and Pope, J.C. (2011) Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America. Third. Boston: Longman, Inc.

Fleisher, R., and J.R. Bond. 1988. Are there two presidencies? yes, but only for republicans. Journal of Politics 50 (3): 747–767.

Gadarian, S.K. 2010. The politics of threat: how terrorism news shapes foreign policy attitudes. Journal of Politics 72 (2): 469–483.

Gadarian, S.K. 2014. Scary pictures: how terrorism imagery affects voter evaluations. Political Communication 31 (2): 282–302.

Gelpi, C., P. Feaver, and J. Reifler. 2009. Paying the Human Costs of War. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Groeling, T., and M. Baum. 2008. Crossing the water’s edge: elite rhetoric, media coverage, and the rally-round-the-flag phenomenon. Journal of Politics 70 (4): 1065–1085.

Guisinger, A., and E.N. Saunders. 2017. Mapping the boundaries of elite cues. International Studies Quarterly 61 (2): 425–441.

Hildebrandt, T., et al. 2013. The domestic politics of humanitarian intervention. Foreign Policy Analysis 9 (3): 243–266.

Iyengar, S., G. Sood, and Y. Lelkes. 2012. Affect, not ideology: a social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (3): 405–431.

Iyengar, S., et al. 2019. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1): 129–146.

Jentleson, B., and R.L. Britton. 1998. Still pretty prudent: post-cold war american public opinion on the use of military force. Journal of Conflict Resolution 42 (4): 395–417.

Kam, C.D., and J.M. Ramos. 2008. Joining and leaving the rally: understanding the surge and decline in presidential approval following 9/11. Public Opinion Quarterly 72 (4): 619–650.

Kiley, J. (2017) ‘U.S. public sees Russian role in campaign hacking, but is divided over new sanctions’, Pew Research Center, 10 January. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/10/u-s-public-says-russia-hacked-campaign/ (Accessed: 9 June 2017).

Krebs, R.R. 2015. Narrative and the Making of US National Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kreps, S., and S. Maxey. 2018. Mechanisms of morality. Journal of Conflict Resolution 62 (8): 1814–1842.

Kreps, S., E.N. Saunders, and K. Schultz. 2018. The ratification premium: hawks, doves, and arms control. World Politics 70 (4): 479–514.

Kriner, D., and F. Shen. 2014. Responding to war on capitol hill. American Journal of Political Science 58 (1): 157–174.

Kriner, D., and F. Shen. 2015. Conscription, inequality, and partisan support for war. Journal of Conflict Resolution 60 (8): 1419–1445.

Lee, F.E. 2009. Beyond Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, C.A. (2020) ‘Polarization, Casualty Sensitivity, and Military Operations: Evidence from a Survey Experiment’. Workshop on Domestic Polarization and US Foreign Policy: Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Implications.

Levendusky, M.S. 2009. The Partisan Sort. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M.S. 2018. Americans, not partisans: can priming American national identity reduce affective polarization? The Journal of Politics 80 (1): 59–70.

Levendusky, M.S., and M.C. Horowitz. 2012. When backing down is the right decision. Journal of Politics 74 (2): 323–338.

Malhotra, N., and E. Popp. 2012. Bridging partisan divisions over antiterrorism policies. Political Research Quarterly 65 (1): 34–47.

Mason, L. (2016) ‘A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(Special Issue), pp. 351–377.

Mason, L. (2018a) ‘Ideologues without Issues: The Polarizing Consequences of Ideological Identities’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(Special Issue), pp. 866–887.

Mason, L. 2018b. Uncivil Agreement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mattes, M., and J.L.P. Weeks. 2019. Hawks, doves, and peace. American Journal of Political Science 63 (1): 53–66.

Maxey, S. 2020. The power of humanitarian narratives. Political Research Quarterly 73 (3): 680–695.

McAdam, D., and K. Kloos. 2014. Deeply Divided. New York: Oxford University Press.

Michelitch, K., and S. Utych. 2018. Electoral cycle fluctuations in partisanship. Journal of Politics 80 (2): 412–427.

Milner, H., and D. Tingley. 2013. The choice for multilateralism. Review of International Organizations 8 (3): 313–341.

Milner, H., and D. Tingley. 2015. Sailing the Water’s Edge. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Myrick, R. (2020) ‘The Reputational Consequences of Polarization for American Foreign Policy: Evidence from the US-UK Bilateral Relationship’. Workshop on Domestic Polarization and US Foreign Policy: Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Implications.

New York Times/CBS News (2016) CBS News/New York Times Poll: 2016 Presidential Campaign/Economy/Immigration/Police and Race Relations in the U.S., 2016 . Roper #31102964, Version 2. Ithaca, NY: Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS) [producer] Cornell Unviersity Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31102964 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Pattison, J. 2010. Humanitarian Intervention and the Responsibility to Protect. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pew Research Center (2013) ‘Modest Support for Military Force if Syria Used Chemical Weapons’, Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 29 April. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/2013/04/29/modest-support-for-military-force-if-syria-used-chemical-weapons/ (Accessed: 24 May 2017).

Pew Research Center (2017a) ‘Public Supports Syria Missile Strikes, but Few See a “Clear Plan” for Addressing Situation’, Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 12 April. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/2017/04/12/public-supports-syria-missile-strikes-but-few-see-a-clear-plan-for-addressing-situation/ (Accessed: 24 May 2017).

Pew Research Center (2017b) ‘The World Facing Trump: Public Sees ISIS, Cyberattacks, North Korea as Top Threats’, Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 12 January. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/2017/01/12/the-world-facing-trump-public-sees-isis-cyberattacks-north-korea-as-top-threats/ (Accessed: 9 June 2017).

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press (2016a) Pew Research Center: August 2016 Political Survey . Roper #31096310, Version 2. Ithaca, NY: Princeton Survey Research Associates International [producer]. Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31096310 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press (2016b) Pew Research Center: June 2016 Voter Attitudes Survey, 2016 . Roper #31096308, Version 2. Ithaca, NY: Abt-SRBI of New York [producer], Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31096308 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press (2016c) Pew Research Center: October 2016 Political Survey, 2016 . Roper #31096311, Version 2. Ithaca, NY: Princeton Survey Research Associates International [producer]. Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31096311 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Pew Research Center, U.S. Politics and Policy, 1615 L. (2014) ‘Bipartisan Support for Obama’s Military Campaign Against ISIS’, Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 15 September. Available at: http://www.people-press.org/2014/09/15/bipartisan-support-for-obamas-military-campaign-against-isis/ (Accessed: 24 August 2016).

National Election Pool (ABC News, Associated Press, CBS, CNN, Fox News, NBC) (2016) National Election Pool Poll: 2016 National Election Day Exit Poll, 2016 . Roper #31116396, Version 3. Ithaca, NY: Edison Research [producer], Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31116396 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Prather, L. (2020) ‘Values at the Water’s Edge: Social Welfare Values and Foreign Aid’, Working Paper, pp. 1–39.

PRRI (2016) PRRI Poll: American Values Survey, 2016 . Roper #31114143, Version 2. Ithaca, NY: PRRI [producer], Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31114143 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Rathbun, B.C. 2004. Partisan Interventions. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Rogowski, J.C., and J.L. Sutherland. 2016. How ideology fuels affective polarization. Political Behavior 38: 485–508.

Schultz, K. 2017. Perils of polarization for U.S. foreign policy. The Washington Quarterly 40 (4): 7–28.

Sood, G. and Iyengar, S. (2016) Coming to Dislike Your Opponents: The Polarizing Impact of Political Campaigns. SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2840225. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2840225.

Tama, J. (2018) ‘The Multiple Forms of Bipartisanship: Political Alignments in US Foreign Policy’, Social Science Research Council, 19 June. Available at: https://items.ssrc.org/democracy-papers/the-multiple-forms-of-bipartisanship-political-alignments-in-us-foreign-policy/ (Accessed: 21 August 2019).

Tama, J. (2019) ‘Forcing the President’s Hand: How the US Congress Shapes Foreign Policy through Sanctions Legislation’, Foreign Policy Analysis, Forthcoming, pp. 1–20.

Trager, R.F., and L. Vavreck. 2011. The Political Costs of Crisis Bargaining. American Journal of Political Science 55 (3): 526–545.

The Washington Post/ABC News (2016) ABC News/Washington Post Poll: Clinton-Trump Race/Candidate Popularity, 2016 . Roper #31113963, Version 3. Ithaca, NY: Langer Research Associates [producer], Cornell University Roper Center for Public Opinion Research [distributor]. Available at: https://doi.roper.center/?doi=https://doi.org/10.25940/ROPER-31113963 (Accessed: 18 September 2021).

Wallace, G.P.R. 2013. International Law and Public Attitudes Towards Torture. International Organization 67 (1): 105–140.

Webster, S.W., and A.I. Abramowitz. 2017. The Ideological Foundations of Affective Polarization in the U.S. Electorate. American Politics Research 45 (4): 621–647.

Western, J. 2005. Selling Intervention and War. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wildavsky, A. 1966. The Two Presidencies. Trans-Action 4: 7–14.

Wittkopf, E.R. 1994. Faces of Internationalism in a Transitional Environment. Journal of Conflict Resolution 38 (3): 376–401.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maxey, S. Finding the water’s edge: when negative partisanship influences foreign policy attitudes. Int Polit 59, 802–826 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00354-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00354-9