Abstract

The government of the UK is reputed to be among the world’s most transparent governments. Yet in comparison with many other countries, its 5-year-old register of lobbyists provides little information about the lobbying activity directed at the British state. Further, its published lists of meetings with government ministers are vague, delayed, and scattered across numerous online locations. Our analysis of more than 72,000 reported ministerial meetings and nearly 1000 lobbying clients and consultants reveals major discrepancies between these two sources of information about lobbying in the UK. Over the same four quarters, we find that only about 29% of clients listed in the lobby register appear in the published record of ministerial meetings with outside groups, and less than 4% of groups disclosed in ministerial meetings records appear in the lobby register. This wide variation between the two sets of data, along with other evidence, contribute to our conclusion that the Government could have made, and still should make, the lobby register more robust.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The UK ranks number one in the world in terms of the openness of its government data.Footnote 1 This puts the UK ahead of, respectively, the USA, France, Canada, Germany, and Japan. The British public has access to open data regarding budget, spending, legislation, elections, British companies, trade, the performance of education and health agencies, crime, and more. Yet when it comes to lobbying, the UK is still quite opaque.

Following a high volume of scandals, as well as domestic and international pressure, the Conservative–Liberal Democrat Government created in 2014 the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists. The overdue register this office oversees is notably weaker than advocates requested, and it is inadequate compared to lobbying disclosure laws in many other countries. Similarly, the data the Government has published since 2010 about ministerial meetings with external groups are unwieldy, unclear, and unpunctual. We identify five aspects that together suggest that the Government purposely chose to keep lobbying in the UK in the dark. These findings are summarized as follows:

- 1.

Lobbying regulation in the UK is among the very weakest of countries that have developed lobbying disclosure laws;

- 2.

The set of lobby clients listed in the register is significantly different from the set of groups with whom ministerial offices report having met;

- 3.

Collating information about ministerial meetings is too burdensome for any layperson to do;

- 4.

The debate surrounding lobbying transparency as the law was being written made clear that the proposal was not robust enough; and

- 5.

Lobbying clients meet more frequently with Government ministers than unregistered groups, and a small number of lobby clients dominate over the others.

In short, we join with others (Chari et al. 2019; Pegg 2015; McGrath 2009; Miller and Dinan 2008; Jordan 1998) who recognize the need for a more robust lobbying regime in the UK.

UK lobbying regulation in international comparison

In recent years, the world has seen a remarkable expansion of lobbying regulations. In 2000, there were five national or supranational jurisdictions with lobbying disclosure requirements—the U.S. (1946, 1996, 2008), Germany (1951Footnote 2), Canada (1989, 2003, 2008), Georgia (1998), and the European Parliament (1996).Footnote 3 Since then, 13 additional countries have established lobbying regulations—Lithuania (2001), Poland (2005), Taiwan (2008), Israel (2008, 2010), France (2009, 2016), Mexico (2010), Slovenia (2010), Netherlands (2012), Austria (2013), Chile (2013), the UK (2014), Ireland (2015), and Italy (2017)—as well as the European Commission (2008). Lobbying reform has been attempted but has failed to fully materialize in Brazil, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Spain, and other jurisdictions, including Hungary, where a lobbying reform law was adopted (2006) and then repealed (2011), and North Macedonia, where a law was created but never implemented (Holman and Luneburg 2012; Crepaz 2017b). The rapid expansion is partly due to successful policy learning/transfer/diffusion (Radaelli 2000; Graham, Shipan and Volden 2013) and partly due to external and internal pressure (e.g., Pegg 2015; Miller and Dinan 2008). Such pressure is often instigated by widespread media attention to lobbying scandals (Allen 2002; Ozymy 2013).

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2014 asserted that governments should require lobbying activities to be disclosed in a manner that is transparent and accessible to the general public. OECD highlights five elements of effective regulation: an unambiguous definition of lobbying; disclosure of funding sources; disclosure of lobbying targets; clear standards of behavior regarding especially revolving-door practices; and appropriate monitoring and enforcement. Similarly, the U.S. Center for Public Integrity (CPI) defines eight key components of lobbying regulation (2003). In its view, effective lobbying regulations should unambiguously define lobbying; mandate the registration of individual lobbyists and clients by name; require disclosure of expenditures on lobbying by client and lobby firm; provide for electronic filing; ensure public access to the registry; include enforcement provisions; and specify revolving-door provisions, especially cooling-off periods for government employees. Opheim (1991), Newmark (2005), and Holman and Luneburg (2012) have similarly developed criteria for assessing the robustness of lobbying regimes; Chari et al. (2019) find that the correlations between these methods and those of the CPI are .80, .62, and .65, respectively. While the CPI criteria, especially the focus on disclosure of financial information, may be more suitable for the U.S. than for other jurisdictions (Chari et al. 2019), Chari et al. (2019) rate CPI’s index as having the highest content validity among these alternatives (i.e., it best captures the robustness of a lobbying regime). As such, our criteria for evaluating the lobbying regulations in the UK are based primarily on those of the CPI.

At the high end of robustness of lobbying regulatory schemes, the Center for Public Integrity gives the U.S. 62 out of 100 possible points. At the federal level in the U.S., lobbying is clearly defined as contacting officials about matters of public policy. Anyone who spends more than 20% of their time communicating with government officials in either the legislative or executive branch and is paid more than $3000 for a client in a quarter (or $11,500 for in-house lobbyists) must register. Every quarter lobbying organizations report the identities of their clients, the names of individual lobbyists working for each client, the issue areas about which they lobby for each client, as well as the bill numbers or titles of legislation they lobby about for each client and in each issue area. Failure to report is punishable by up to a year in prison and a fine of up to $50,000.Footnote 4 The House defeated an amendment that would have created an enforcement agency, however (Chari et al. 2019, 22). Since 2008, U.S. lobbyists must also disclose their own federal campaign contributions and those of any political action committee (PAC) the lobbyist “controls.” (A PAC is a fundraising organization that donates to federal candidates and is associated with a company, union, or nonprofit organization.) Gift-giving to government employees or the members of their household is prohibited without explicit permission by the House or Senate ethics committee. Staff who leave government service must wait one or two years (depending on their level in government) before registering as lobbyists. While the U.S. is considered the most robust system of any nation, 20 U.S. states have higher scores than the federal government (Chari et al. 2019), and LaPira and Thomas (2017) estimate that more than half (52%) of U.S. federal lobbying activity still goes unregistered, especially lobbying in the executive branch.

Using the CPI’s quantitative method for assessing the stringency of lobbying legislation, Keeling et al. (2017) give the UK a significantly lower score than the U.S., at 33, tying it with Australia and putting it above the European Union (32) and France (30), among others. A score of 30–60 classifies a system as medium-robust (Chari et al. 2019). Chari et al. (2019) describe medium-robust regimes as requiring individual lobbyists to disclose their personal identities, as well as the issue, bill, or government institution they are lobbying; medium-robust countries also limit or prohibit lobbyists from giving gifts or contributions to politicians and they require former legislators to observe a cooling-off period between being a registered lobbyist and working for government. However, none of these requirements apply in the UK. In Britain, only consultant lobbying firms must register—not campaigning organizations and not “in-house” lobbyists, even though the Government estimated that the number of in-house lobbyists—those who are employed by the businesses and organizations for whom they lobby—could be six times more than the number who work on contract as lobbying consultants (Cabinet Office 2013). This leaves a significant blindspot in the register. Further, the names of individual lobbyists are not reported, nor are the targets, expenditures, or subject matter of lobbying activities. There are no restrictions on gift-giving or revolving-door employment.

These limitations challenge the classification of the UK as “medium-robust” according to the criteria set out by Keeling et al. (2017) which has been reproduced elsewhere including the second edition of the book Regulating Lobbying (Chari et al. 2019). In particular, we take issue with Keeling et al.’s (2017) coding of the UK system in two respects. First, Keeling et al. gave the UK full credit (4 points under CPI’s scheme) for requiring every lobbyist to register with no minimum threshold for money spent. In fact, however, UK lobby firms need not register if they do not have a VAT number, which requires an annual revenue of £85,000 or more. The CPI gives 0 points if the threshold is higher than $500. Second, Keeling et al. give the UK credit (3 points) for requiring individual lobbyists to register, when in fact only consultant lobbying firms must register, not the individuals who work for the consultancy, nor any in-house lobbyists. CPI gives 0 points if individual lobbyists are not required to register. These corrections reduce the UK total score from 33 to 26, and this score moves the UK into the “low robustness” category (Chari et al. 2019). It is now ahead of only two systems that are in effect today—those of the Netherlands and “the strange case” of Germany (Ronit and Schneider 1998).

Creation of a minimalist lobby register

The establishment of an official and mandatory register of lobbying in Britain was first discussed by the Select Committee on Members’ Interests in 1991, but no measures were adopted. Twenty years later, Conservative Party Prime Minister David Cameron called lobbying “the next big scandal waiting to happen” (Porter 2010). Indeed, in the following 5 years there were 15 lobbying scandals in Britain (Transparency International 2015), with names such as “Cash for Amendments” (2009), “Cash for Influence” (2010), and “Cash for Questions” (2013). Meanwhile, the OECD was recommending (2009) to its then 30 member nations that they adopt greater transparency of government activity, and jurisdictions including Estonia, Slovenia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Mexico, and the European Union all considered creating or strengthening laws that govern lobbying activities.

Announcing that “Transparency is at the heart of this Government’s agenda,”Footnote 5 the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition Government created in 2014 a mandatory register of consultant lobbyists. The Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act requires consultant lobbyists (also known as contract or third-party lobbyists) to register with the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists, overseen by the Cabinet Office. Registered consultant lobbyists must disclose quarterly a list of clients —and that is all. The Government itself estimated that the exclusion of in-house lobbyist from the requirement to register would leave 85% of lobbying unreported (Cabinet Office 2013). The register specifically excludes several types of communication with government officials from the need for registration, including communication between client organizations and Government, communication with senior civil servants and ministers’ special advisers, and communication with government officials by organizations not represented by a consultant lobbyist. Violators may be fined but are not subject to prison time. Lobbyist gift-giving is allowed, and no revolving-door provisions exist. And although the three British associations that represent lobbyistsFootnote 6 had operated under a long-standing shared code of conduct, the Government chose not to include in the statute this code of conduct or any other rules of behavior.

The House of Common’s Public Administration Select Committee (2009) had recommended much more stringent regulations, which would have required that both consultant and in-house lobbyists register; that lobbyists report previously held public office jobs and that senior public officials disclose their previous private-sector employment; that details of meetings be disclosed including dates and topics discussed, if not full minutes; that gifts and hospitality be disclosed; and that compliance be monitored and enforced by a body independent of lobbying organizations and of the Government. The committee also recommended strengthening the existing Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, a part-time, unpaid, Cabinet Office committee that advises the Prime Minister on the ethics of proposed appointments of “revolving-door” government officials as they enter the private sector. Of these, only the recommendation that registering be mandatory (or lobbyists would not be allowed to meet with officials), rather than voluntary, was adopted in the law.

While mandatory registration is a step in the right direction (Kanol 2012), the Government missed the opportunity to make lobbying regulation more rigorous, as requested by stakeholders. A total of 259 comments submitted about the proposal during the consultation period (80 representative bodies and trade associations, 34 civil society organizations, 34 companies, 10 trade unions, 10 research organizations, 9 campaign groups, 78 individuals, 3 regulators, and one Member of Parliament; Cabinet Office 2012). Crepaz (2017a) reviewed these and found that 85% wanted the law to be stricter than proposed. Opposition party members called the proposal “ridiculously narrow”Footnote 7 and speculated that it would likely “make lobbying more opaque, rather than more transparent.”Footnote 8

The Government and some who submitted comments argued that further regulations could become burdensome and costly; that publishing financial information in the register would breach commercial confidentiality; that disclosure of staff lists from organizations working on high-profile and contentious issues would put individual people at risk; that adherence to a further code of conduct would be unproportionate and add additional burden on organizations already subscribing to wider industry codes; and that it was questionable whether a register would have any significant impact on lobbyists’ behavior (Cabinet Office 2012). We think a more plausible explanation is that the Government was more interested in publicly embracing transparency and accountability than it was in inviting public scrutiny of its private discussions and decision-making (see also Vargovčíková 2017, who makes a similar argument regarding attempts at regulating lobbying in Poland and the Czech Republic).

Difficult-to-use data on meetings with government ministers

In pursuit of transparency, and at least somewhat in response to the multiple lobbying scandals, in 2010 the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition established in the Ministerial Code a new requirement that British Government departments disclose quarterly lists of the external groups who met with government ministers. Each department uploads its own lists in its own format. The name of the organization or individual, the quarter in which they met with the minister or permanent secretary, and the purpose of the meeting must be reported, though the purpose is often listed as “general discussion” or similarly vague language. No additional information is required, though more information exists: minutes are generally kept, and the meetings are audio-recorded and frequently transcribed. The government argued that making available the minutes of meetings between all outside interests and government ministers would be costly and time-consuming.

Quarterly reports are filed online at www.gov.uk under the heading “transparency data,” along with tens of thousands of other government documents that might relate to transparency (e.g., salary disclosure data, hospitality and gifts, departmental spending). Thus, to get to ministerial meetings data, one has to search manually using either a keyword search (“meet*”) or by browsing the publication database by department and time period. While the data are arranged quarterly, they are not updated nearly as often as every quarter. Further, the published records are disclosed in different formats and with varying titles: For our period of analysis from the first quarter of 2011 up to and including the fourth quarter of 2015 there were 234 PDFs, 700 comma-separated value files, 52 MS Excel worksheets, 23 MS Word documents, six Open Document spreadsheets, 24 Open Document texts, and six rich text files. Some reports contained only meetings with external groups, others combined these with gifts, hospitality, and overseas travel reports; some reports separately reported meetings of individual ministers or secretaries, others synthesized all meetings of a department’s senior staff in one document; occasionally data from more than one quarter were included in a single document. As a result of these challenges, the meetings data are seldom analyzed (exceptions are Dommett et al. 2017 and Transparency International 2015).Footnote 9

Focusing specifically on the evaluation of the usability of transparency data for member of the public (one of the CPI’s stringency criteria mentioned before), we follow Piotrowski and Liao (2012), who identify a set of criteria—accuracy, accessibility, completeness, understandability, timeliness, and low cost—which can be applied to any government transparency data. Following Holman and Luneburg (2012), we add as another criterion whether the provided data are searchable, so that comprehensive, comparative, and specially targeted database queries are possible. We now evaluate the ministerial meetings data according to these usability criteria.

Accuracy

(preciseness, factuality) The meetings data offer little information about the meetings other than the broad “purpose of the meeting.” Among the most commonly stated purposes are generic descriptions such as “trade and investment,” “energy issues,” or “tax matters.” And some are even less precise: More than 2500 entries refer to “general discussions,” another 2500 to “introductory” meetings, 1050 to “catch-up” meetings, around 450 to “regular meetings,” around 250 to “general meetings,” and around 550 to either “routine meeting,” “talk meeting,” or “roundtable discussion.” In an additional 200 cases, the purpose of the meeting is not reported at all. A total of 10% of our acquired reports fail to offer any policy-specific information about what was discussed in any of the meetings listed.

Another problematic aspect is the frequent disclosure of individuals’ names without any indication of organizational affiliation. In a random sample of 5% of the groups listed in the meetings data, we identified 53 such cases (5.2%). Examples include Jacqueline Gold, CEO of the multinational retail company Ann Summers; Jin Liqun, who was helping the government to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; and Michael Hintze, founder and chief executive of CQS, a credit asset management firm. While most of these individuals have some level of prominence, ordinary citizens cannot be expected to recognize their names and link them to the organizations they represent. The vague descriptions of the purpose of meetings and the omission of organizations’ names suggest they are what Piotrowski and Liao (2012) would label “intentional concealment.”

Accessibility

Online access to the meetings data is public and open; no registration is necessary. All files can be accessed via either the general gov.uk website or the publications section of the individual department websites. All files can be downloaded in the format provided by the source. Files provided in the .csv format can also be previewed in-browser.

Completeness

By the middle of 2016, 92.6% of the 877 required quarterly reports were available for the years 2011–2015. (The “877” is a function of 20 quarters x 44 department positions, minus three quarters during which the office of the Deputy Prime Minister no longer existed.) The data cover only the top two of the three tiers of government ministers (the Secretaries of State and the Ministers of State; only the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development also consistently reported meetings by their Parliamentary Under-Secretaries of State) plus the top level of the Civil Service (the Permanent Secretaries). However, the 5000 senior civil servants at the next levels do not have to report their meetings, nor do Special Advisers to ministers (their political staff). One department, Export Finance, had not published any meeting disclosures by mid-2016. The incomplete data provided and nondisclosure of meetings with other levels of government suggest a substantial shortfall in fulfilling Piotrowski and Liao’s (2012) specification that “all necessary parts” be published.

Understandability

All meetings disclosures are arranged and written in a way that makes them easily understandable. For the most part, the reports eschew technical language and the use of uncommon acronyms. Filers could possibly argue that the use of generic statements of the meetings’ purposes increases their understandability for the lay public; however, their lack of accuracy and completeness is better described as a hindrance to transparency and open government.

Timeliness

As mentioned above, our data collection during the third and fourth quarters of 2016 revealed that 7.4% of quarterly reports from the years 2011 to 2015 were still not available online. Moreover, almost 30% of reports about the first quarter of 2016 and 21% of reports about the fourth quarter of 2015 had not yet been uploaded, which indicates a failure on the part of departments to provide their transparency information in a timely manner.

Free or low cost

Apart from acquisition costs and internet access fees, access to the quarterly meetings reports is free of charge.

Searchability

The biggest usability obstacle is the lack of a complete and searchable database of ministerial meetings with external groups. Meeting reports are found in the publications database at gov.uk; they do not have their own site. This means users have to search and sift through a very large database of different document types to reach the meetings data. To give but one example: a keyword search for “BAE Systems” Inc., a company that has met with department officials 383 times between 2011 and 2015, with the filter “transparency data” for publication type at www.gov.uk/government/publications, yields 309 results, including documents about transactions, departmental spending, and contracts. And users still may not have a comprehensive set of what is available, since there is no website dedicated to meetings disclosure. It is also not possible to do a reliable targeted search for either external groups or Ministers/Secretaries. Considerable time and skill are required to collect, synthesize, and clean the disparate data.

Based on these criteria, the usability of the Ministerial Meetings data for citizens at large can be categorized as low. In Piotrowski and Liao’s four-quadrant typology of the relationship between transparency and usability (2012, 86), we would assign the UK to the “overload” designation “in which government information is disclosed in large amounts, but without sufficient attention to information usability” (Piotrowski and Liao 2012, 88).

The mismatch between groups that lobby and groups that meet with government ministers

Despite their numerous limitations, we now have access to plentiful data about the names of external groups that are meeting with particular British ministerial offices. We identified and collected 1045 files containing information about the ministerial meetings of 23 UK Government departments (including the Offices of the Leaders of the House of Commons and House of LordsFootnote 10) from the first quarter of 2011 through the last quarter of 2015.Footnote 11 In total the files include 72,756 recorded contacts between a ministerial department senior official and an external organization or individual. This is the greatest number of meetings between government officials and outside interests that has ever been included in a single data set (in a similar study, Dommett et al. 2017 retrieve and code 6192 meetings).

To calculate the number of unique entities with one or more meeting, a second data set was created which eliminated all semantic duplicates in the “external group” column. All acronyms were checked via a Google search, and entries’ designations in both data sets were changed to the full designation of the group. To also account for small differences in how organizations were designated (as well as typing errors), we used the Fuzzy Lookup add-on for MS Excel. All matched pairs with a matching score higher than 0.90 were checked for congruence and the designation of all entries referring to the same group—both in the list of organizations and the original list of all meetings—were standardized in a new variable according to the designation most commonly used by the group itself. The Fuzzy Lookup procedure also yielded matches for direct subsidiaries of business conglomerates (e.g., “Vodafone UK” and “Vodafone Group”); these were standardized under a single name (e.g., “Vodafone”). A manual check revealed further duplicates that could not be detected through semantic criteria; as examples, the “Anglican Church” was merged with the entry which uses the more commonly used designation “Church of England,” the “Government of Singapore Investment Corporation” was merged with the entry “GSIC Limited,” and “Harrow Council” was merged with the entry “Harrow London Borough Council.”

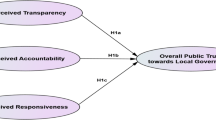

Figures 1 and 2 show the overlap between unique groups in the two sets of data. The light gray shows Type I error in the lobby register—lobbyists’ clients who have no reported meetings with government ministers. The dark gray shows Type II error in the register—groups that meet with government officials but are not included in the register. The overlap is the set of groups that appear in both sources of data. The two sets of data overlapped temporally in the four quarters of 2015; as such we provide statistics for the 2015 data alone in Fig. 2, and Fig. 1 presents the full data set—2011–2015 for meetings, and the first quarter of 2015 through the third quarter of 2016 for the register. For both data sets, the starting date is when the data began and the ending date is a function of when we wrote the first draft of this paper.

Overlap between groups in the lobby register and groups in the ministerial meetings data in the UK. Notes: The data describe groups in the lobby register for the seven quarters starting in January of 2015 and groups in the ministerial meetings data for the 5 years from 2011 to 2015. Circles and overlap are proportional in size to the populations indicated. Our analysis indicates that 44% of lobby clients and consultants in the lobby register appear in the meetings data, and just 2% of the groups in the meetings data appear in the lobby register

Overlap between groups in the lobby register and groups in the ministerial meetings data in 2015. Notes: Circles and overlap are proportional in size to the populations indicated. The data show that in 2015, 29% of lobby clients and consultants appear in the meetings data, and only about 3% of groups in the meetings data appear in the lobby register

Meetings without lobbyists

Only 2% of groups that we know met with government ministers and permanent secretaries in the 2011–2015 time frame are listed in the lobby register during the seven quarters starting in January of 2015. In the shared time frame of the four quarters of 2015, just less than 4% of groups mentioned in the ministerial meetings data also appear in the register of consultant lobbyists. Counting in terms of meetings rather than groups, 91% of reported ministerial meetings (and 91% in 2015 alone) were with groups and individuals whose names do not appear as clients in the lobby register. These high numbers were anticipated by the Public Relations and Communications Association and openly discussed during the bill’s debate on the floor of the House.Footnote 12

Lobbyists that don’t lobby

Our analysis shows that 44% of the 918 clients and 116 consultant lobbying firmsFootnote 13 that are listed in the register in 2015–2016 also appear in the ministerial meetings data of 2011–2015. Restricting the sample to the 12 months for which we have data from both sources, Fig. 2 shows that just 250 of the 852 groups that appear in the register—29%—also appear among the 7303 groups in the meetings data.

The differences between data from different time periods suggest that lobbyists may register their clients as a matter of course or routine, while their meetings with ministers are intermittent and dependent on current events and shifting government priorities. Or, it may be that lobbying consultants find professional benefits to registering even if they are not actively communicating about policy with high-level ministers, which is an argument lobbyists made before the register was created. Alternatively, the issue may be that lobbyists meet most frequently with Special Advisers and civil servants (Zetter 2008), neither of which publish their meetings. Only officials in the top two levels of government—ministers, secretaries, and the leaders of the House of Commons and House of Lords—report their meetings activity, while lobbyists likely have more meetings with lower-level employees. Thus, there may be a large number of meetings between government officials and lobbyists that are not reported—and are not required to be.

The skewed distribution of ministerial meetings across groups

In addition to the many groups that meet with government officials but do not register as lobbying organizations, we know very little about the groups that are registered. This absence matters because registered lobby clients account for a disproportionate number of meetings. In 2015, the 3.4% of groups that appear in the meetings data that are also lobby clients account for 8.6% of meetings. Across the 5-year period, the average group in the meetings data appears 3–4 times, while the average lobby client appears in the meetings data 17 times. (In 2015, the average group meets twice with ministers’ offices while the average lobbying client attends five meetings.)Footnote 14 Thus, the lobbying clients listed in the register are groups that the Government listens to, or at least meets with, especially frequently (Fig. 3).

Even if we disregard the lobby clients, the meetings data are distributed unequally. As seen in Table 1, 15 of the 25 most active lobby groups seen in the ministerial meetings data are not listed as lobbying clients in the register. These include umbrella business associations, such as the Confederation of British Industry and the British Chambers of Commerce, as well as companies with household names, such as the BT Group (formerly British Telecom), Shell, BP (British Petroleum), and Rolls-Royce, which together attended 960 meetings with government ministers in the 5 years between 2011 and 2015. The two-thirds of groups listed in the meetings data that attend just one meeting account for 20% of the meetings. Meanwhile, the 10% most frequent visitors account for 60% of all meetings with department officials, and the 1% most frequent visitors are present at 27% of the meetings. Among groups that meet with ministers that are also listed in the register, the top decile of most frequent visitors accounts for 64% of the meetings (45% in 2015 alone), and the top 1% are present at 14% of all meetings with department officials (8% in 2015 alone). This uneven distribution is evidence that some lobbyists have far greater access than others (also see Dommett et al. 2017). Yet users of the two data sets know nothing about the identities of these lobbyists, what measures they are lobbying about, or how much money may be involved.

Discussion

Why did the UK Government choose not to adopt stricter lobbying regulations in 2014? Let us examine the Government’s stated reasons. First, the Government argued that additional requirements would be too costly and burdensome. We think it would not be costly or burdensome, and might even reduce the cost and burden, if ministers’ offices were given a common form, format, or online portal for reporting meetings. It would also not be costly and burdensome to the Government to ask consultant lobbyists to supply, in addition to the names of their clients, the names or offices of their lobbying targets as well as the subjects on which they were lobbying. Second, the Government claimed that greater disclosure of lobbying practices could lead to competitive advantages and disadvantages for registered lobbyists—but even if true, this would not affect Government, only lobbyists. Third, the government argued that the purpose of the register was simply to complement the meetings data that was already being published because “it remains unclear exactly whose interests are being represented when consultant lobbyists meet with government” (Cabinet Office 2013). But this disclosure was both unnecessary and unfulfilled: Our data show that lobby firms account for less than 1% of external groups in the meetings data and less than 1% of meetings. In fact, consultants named in the 2015 data were mentioned in the meetings data only five times before the 2014 law was adopted. Across the 5-year period, by our count, the meetings data include the names of 31 known consultant lobbyists, while the same data contain 431 registered lobby clients. Moreover, even in those relatively few cases in which a consultant firm is mentioned as having met with a government minister’s office, we still do not know on whose behalf the consultant lobbyist was working, since the register shows that firms represent 8–9 clients on average. So, the explanation that the purpose of the register was to identify the clients of lobbyists' meeting with departments does not hold water. In summary, we find that none of the Government’s arguments for its minimalist register withstand close scrutiny, especially given the significant and growing number of other jurisdictions that now regulate lobbying around the world.

Crepaz (2017a) argues that the UK regulation is yet another example of how right-leaning political parties in government share an ideological preference for low-regulation lobbying. Crepaz concludes that lobbying scandals had only an “agenda-setting effect” on the UK’s lobbying law. We think that, while the Government may well have had an ideological commitment to “light touch” governance, the main reasons the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition Government created a lobby register were to respond to criticism and to prevent future lobbying scandals. Less charitably, the objective might also have been to obscure the fact that ministers and their offices spend about 60% of their external group meetings with the 10% of groups that visit most frequently, and that they spend 27% of their meetings with the most frequently visiting 1% of groups. This fact is consistent with the idea that politicians across Governments are cross-pressured to demonstrate a commitment to public accountability while keeping much of their decision-making processes private.

Conclusions

The late Grant Jordan contended that an examination of lobbying is essential to understanding contemporary British politics (1991, vii), and lobbying in Britain is considered by some to be “the most developed” in Western Europe (Miller and Dinan 2008). Yet the centrality of lobbying in the UK is belied by the inadequate rules governing disclosure of lobbying activities.

We make four critiques of the UK government’s transparency efforts regarding lobbying. First, the 5-year-old lobby register misses the majority of lobbying that occurs in London, especially lobbying by those firms and campaigning organizations that lobby on their own behalf. The names, targets, and expenditures of lobbyists are not reported, let alone the subject matter being discussed, and there are no limitations on gift-giving or revolving-door employment. Our corrected application of the criteria of the U.S. Center for Public Integrity, as also used by Keeling et al. (2017) and Chari et al. (2019), puts the UK as among the least robust of lobbying regulation regimes.

Second, the Government’s published data about ministers’ meetings with outside groups, which were touted as an effort toward transparency, are almost totally unusable as provided. Applying the criteria for the usability of government information laid out by Piotrowski and Liao (2012), with the addition of Holman and Luneburg’s (2012) searchability criterion, we conclude that the usability of the meetings data is low.

Third, there is very little overlap between the two sets of data. Our analysis of more than 72,000 meetings reported by government departments shows that the lobby register contains less than 4% of the organizations that we know met with government ministries. Conversely, data about ministerial meetings data contain no records of meetings with as many as 70% of the clients we know contracted with professional lobbying firms.

Fourth, we note a tremendous skew in the distribution of ministers’ meetings with lobby groups. The majority of meetings are held with just 10% of the groups, and more than a quarter of meetings are with just 1% of groups. This skew may be the kind of private information that the Government does not wish to make public.

The inadequacy of the lobby register and the meetings data, combined with the Government’s conscious decision not to adopt stricter regulations, call into question the transparency to which the Coalition Government said it was dedicated. Worse, these lapses make it easy for firms and special interests in the UK to manipulate the policy process out of the public eye. As a result, researchers, journalists, and the public do not know whether or to what extent outside groups are taking advantage of this opportunity to work in relative secrecy—and we cannot find out using the data available.

Change history

04 March 2020

After the article was submitted for review, we continued improving the data. We performed a second attempt to merge groups in the lobby register with groups mentioned in ministerial meetings reports.

Notes

This ranking is conducted by the World Wide Web Foundation in the third edition of its Open Data Barometer Global Report (2016), available at http://opendatabarometer.org.

Despite being among the first countries to regulate lobbying, Germany’s lobbying regulations are comparably quite weak (Ronit and Schneider 1998).

In addition, all 50 U.S. states have a degree of lobbying regulation (Newmark 2005).

According to the law, “knowingly and willfully” failing to report may be punished by up to one year in prison and a fine of up to $50,000; “knowingly and corruptly” failing to comply may result in up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $200,000.

Tom Brake, debate on floor of the House, 22 January 2014.

The three organizations representing the lobbying profession were the Public Relations and Communications Association, the Association of Professional Political Consultants, and the Chartered Institute of Public Relations.

Michael Meacher, debate of the Floor of the House, 3 September 2013.

Jon Trickett, debate of the Floor of the House, 9 September 2013.

For about a year and a half, a website run by the company Moving Flow consolidated these meetings data and provided a searchable interface (http://whoslobbying.com), but they ceased doing so in September 2011.

The Offices of the Leader of the House of Commons and the House of Lords constitute ministerial departments within the Cabinet Office, which is itself a ministerial department of the UK Government.

The Department for Energy and Climate Change became part of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in July 2016, and the Department for International Trade was established in July 2016.

Graham Allen, debate of the Floor of the House, 9 September 2013.

We estimate that less than 1 percent of the meetings listed were with registered lobby consultancies.

These numbers are means; the medians are 1 and 6 for the whole period of the data and 1 and 2 for 2015 alone.

References

Allen, David W. 2002. Corruption, Scandal, and the Political Economy of Adopting Lobbying Policies: An Exploratory Assessment. Public Integrity 4(1): 13–42.

Cabinet Office. 2012. A Summary of Responses to the Cabinet Office’s Consultation Document ‘Introducing a Statutory Register of Lobbyists.’ Presented to Parliament by the Minister for Government Policy. July.

Cabinet Office. 2013. Impact Statement. A Statutory Registry of Lobbyists (as part of the Transparency Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Bill). 9 July.

Center for Public Integrity. 2003. Methodology. The Center for Public Integrity. Updated 19 May 2014. Available at https://publicintegrity.org/state-politics/influence/hired-guns/methodology-5/. Last visited 21 October 2019.

Chari, Raj, John Hogan, Gary Murphy, and Michele Crepaz. 2019. Regulating Lobbying: A Global Comparison, 2nd ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Crepaz, Michele. 2017a. Investigating the Introduction and the Robustness of Lobbying Laws. PhD Thesis, Trinity College Dublin, Department of Political Science.

Crepaz, Michele. 2017b. Why Do We Have Lobbying Rules? Investigating the Introduction of Lobbying Laws in EU and OECD Member States. Interest Groups & Advocacy 6(3): 231–252.

Dommett, Katharine, Andrew Hindmoor, and Matthew Wood. 2017. Who Meets Whom: Access and Lobbying During the Coalition Years. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19(2): 389–407.

Graham, Erin R., Charles R. Shipan, and Craig Volden. 2013. The Diffusion of Policy Diffusion Research in Political Science. British Journal of Political Science 43: 673–701.

Holman, Craig, and William Luneburg. 2012. Lobbying and Transparency: A Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Reform. Interest Groups & Advocacy 1(1): 75–104.

House of Commons Public Administration Select Committee. 2009. Lobbying: Access and Influence in Whitehall. London: The Stationery Office.

Jordan, Grant. 1991. The Commercial Lobbyists: Politics for Profit in Britain. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

Jordan, Grant. 1998. Towards Regulation in the UK: From ‘General Good Sense’ to ‘Formalised Rules’. Parliamentary Affairs 51: 524–537.

Kanol, Direnc. 2012. Should the European Commission Enact a Mandatory Lobby Register? Journal of Contemporary European Research 8(4): 519–529.

Keeling, Sean, Sharon Feeney, and John Hogan. 2017. Transparency! Transparency? Comparing the New Lobbying Legislation in Ireland and the UK. Interest Groups & Advocacy 6(2): 121–142.

LaPira, Timothy M., and Herschel F. Thomas. 2017. Revolving Door Lobbying: Public Service, Private Influence, and the Unequal Representation of Interests, 2017. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

McGrath, Conor. 2009. Access, Influence and Accountability: Regulating Lobbying in the UK. In Interest Groups and Lobbying in Europe: Essays on Trade, Environment, Legislation, and Economic Development, ed. Conor McGrath, 53–123. Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press.

Miller, David, and William Dinan. 2008. Corridors of Power: Lobbying in the UK. Observatoire de la société Britannique 6: 25–45.

Newmark, Adam J. 2005. Measuring State Legislative Lobbying Regulation, 1990–2003. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 5: 182–191.

Opheim, Cynthia. 1991. Explaining the Differences in State Lobby Regulation. Western Political Quarterly 44: 405–421.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2009. Lobbyists, Governments and Public Trust, Volume 1: Increasing Transparency Through Legislation. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2014. Lobbyists, Governments and Public Trust, Volume 3: Implementing the OECD Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Ozymy, Joshua. 2013. Keepin’ on the Sunny Side: Scandals, Organized Interests, and the Passage of Legislative Lobbying Laws in the American States. American Politics Research 41(1): 3–23.

Pegg, David. 2015. “Lobbying Register Covers Fewer than One in 20 Lobbyists—Report.” The Guardian, 21 September 2015.

Piotrowski, Suzanne, and Yuguo Liao. 2012. The Usability of Government Information: The Necessary Link Between Transparency and Participation. In The State of Citizen Participation in America, ed. Hindy Lauer Schachter and Kaifeng Yang, 75–98. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Porter, Andrew. 2010. David Cameron Warns Lobbying is Next Political Scandal. London: The Telegraph. 8 February 2010.

Radaelli, Claudio M. 2000. Policy Transfer in the European Union: Institutional Isomorphism as a Source of Legitimacy. Governance 13: 25–43.

Ronit, Karsten, and Volker Schneider. 1998. The Strange Case of Regulating Lobbying in Germany. Parliamentary Affairs 51: 559–567.

Transparency International. 2015. Accountable Influence: Bringing Lobbying Out of the Shadows. London: Transparency International UK.

Vargovčíková, Jana. 2017. Inside Lobbying Regulation in Poland and the Czech Republic: Negotiating Public and Private Actors’ Roles in Governance. Interest Groups & Advocacy 6(3): 253–271.

World Wide Web Foundation. 2016. Open Data Barometer Global Report, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: World Wide Web Foundation. Retrieved April 20, 2017 (http://opendatabarometer.org/doc/3rdEdition/ODB-3rdEdition-GlobalReport.pdf).

Zetter, Lionel. 2008. Lobbying: The Art of Political Persuasion. Petersfield: Harriman House.

Funding

Funding was provided by Economic and Social Research Council (GB) (Grant No. 102907R).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McKay, A.M., Wozniak, A. Opaque: an empirical evaluation of lobbying transparency in the UK. Int Groups Adv 9, 102–118 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-019-00074-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-019-00074-9