Abstract

Youth unemployment is a big challenge in developing economies, but there is a limited understanding of the dynamics underlying the rise in unemployment among young workers. This article examines youth unemployment and inactivity in India, where the economic contraction from the pandemic was solely responsible for reversing the trend of decades of declining global inequality. Young workers face higher unemployment, have fewer transitions to work, and are more likely to get stuck in unemployment. The pandemic disproportionately pushed young workers out of work and reinforced the pre-existing trends of being more likely to be out of work and stuck in worklessness. Young workers have a strong desire for public employment programmes, with over 80 percent preferring job guarantees among policy options to tackle unemployment in survey experiments. Workers who lose their jobs and become discouraged from finding work afterward are most supportive of a job guarantee.

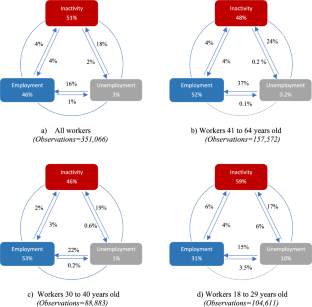

Source: CEP Survey 2021

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2017/2018, informal employment amounted to 88.6 percent of total employment in India, with similar rates in the region (81 percent in Nepal, 94.7 percent in Bangladesh, 81.7 percent in Pakistan), but higher rates than Latin American countries (69.4 percent Peru, 62.4 percent Colombia) and much higher rate than for example South Africa 35.3 percent (Ohnsorge and Yu, 2021).

The CPHS sample had a rural-urban ratio of 34:66 before the lockdown. However, during the period of 24th of March to 7th of April, the rural sample was overrepresented with a ratio of 43:57. This overrepresentation quickly got restored to 36:64 between April and July. In terms of household income, during the lockdown, the share of households in the middle of the income distribution, earning between Rs 150,000 and Rs 300,000 remained at 45%. Nevertheless, there was a change in the tail-ends of the income distribution. There was an over-representation of low-income households and an under-representation of high-income households. Specifically, households earning Rs 500,000 or more made up 13% of the sample before lockdown and 9% during the lockdown. Whereas those earning Rs. 84,000 to Rs.150,000 made up 19.6% of the sample before the lockdown and 25% during the lockdown. Finally, the share of those earning less than Rs.84,000 increased from 2.4% to 4.1% (“CPHS execution during the lockdown of 2020”, available online at consumerpyramidsdx.cmie.com)

A discussion of the representativeness concerns arising from exclusions at the bottom end of the consumption distribution, especially in rural areas, is provided in Drèze and Somanchi (2021), Dhingra and Kondirolli (2022).

Eighteen is the age of majority in India and therefore labor laws differ for 15–17 years old who are covered under child labor laws. The compulsory school leaving age in India is 14 years and therefore some official labor statistics are reported for those between 15 and 29 years old. We exclude individuals between 15 and 17 years from our analysis because they are minors who are also more likely to be pursuing high school education which occurs till age 17. However, including them in our analysis reinforces the main findings further.

International Labour Organization. “ILO Modelled Estimates and Projections database (ILOEST).” ILOSTAT.

The recontacted sample was interviewed over the phone and the boost sample was interviewed door-to-door (in person). Individuals in the control and treatment groups did not interact with each other as the interviews were conducted one on one by trained enumerators.

The MGNREGA figure is computed from disbursements made by the government divided by number of individuals actually worked in 2020. These are available from the NREGA public data portal which put the figure at Rs 5642 precisely. The cash transfer figure is computed from the release of the Press Information Bureau (PIB), Government of India, Ministry of Finance, 08/09/2020 at 1:00PM by PIB Delhi. The figure ranges from about Rs 500 to Rs 1640 depending on the type of recipient.

References

Abraham, R. and Shrivastava, A., 2022. How comparable are India’s labour market surveys? The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 65(2): 321–346.

Arulampalam, W., P. Gregg and M. Gregory. 2001. Unemployment scarring. The Economic Journal 111(475): F577–F584.

Azim Premji University. 2019. State of working India 2019. Centre for Sustainable Employment: Azim Premji University.

Azim Premji University. 2021. State of working India 2021: One Year of COVID-19. Centre for Sustainable Employment: Azim Premji University.

Bandiera, O., A. Elsayed, A. Smurra and C. Zipfel. 2022. Young adults and labor markets in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives 36(1): 81–100.

Banerjee, A., Gopinath, G., Rajan, R. and Sharma, M. 2019. What the economy needs now. Juggernaut Books.

Barford, A., Coutts, A. and Sahal, G. 2021. Youth employment in times of Covid. ILO.

Bentolila, S. and Jansen, M. 2016. Long-term unemployment after the Great Recession: Causes and remedies. CEPR Press

Blanchard, O.J., P. Diamond, R.E. Hall and K. Murphy. 1990. The cyclical behavior of the gross flows of US workers. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1990(2): 85–155.

Boeri, T., Giupponi, G., Krueger, A.B. and Machin, S., 2020. Solo self-employment and alternative work arrangements: a cross-country perspective on the changing composition of jobs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(1): 170–195.

Bosch, M. and Maloney, W. 2008. Cyclical movements in unemployment and informality in developing countries. World Bank Publications.

Browning, M. and E. Heinesen. 2012. Effect of job loss due to plant closure on mortality and hospitalization. Journal of Health Economics 31(4): 599–616.

Burgess, S. and H. Turon. 2005. Unemployment dynamics in Britain. The Economic Journal 115(503): 423–448.

Cho, Y., Margolis, D.N., Newhouse, D. and Robalino, D.A. 2012. Labor markets in low and middle-income countries: trends and implications for social protection and labor policies. Social protection and Labor Discussion Paper; No. 1207. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Chodorow-Reich, G., G. Gopinath, P. Mishra and A. Narayanan. 2020. Cash and the economy: evidence from India’s demonetization. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135(1): 57–103.

Cummings, R.G. and L.O. Taylor. 1999. Unbiased value estimates for environmental goods: a cheap talk design for the contingent valuation method. American Economic Review 89(3): 649–665.

Datta, N. 2019. Willing to pay for security: a discrete choice experiment to analyse labor supply preferences.

Deaton, A. 2021. COVID-19 and global income inequality. LSE Public Policy Review 1(4)

Deshpande, A. 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic and gendered division of paid work, domestic chores and leisure: evidence from India’s first wave. Economics and Politics 39: 75–100.

Dhingra, S. and Kondirolli, F. 2021. City of dreams no more, a year on: worklessness and active labor market policies in urban India. CEP COVID-19 Analysis Paper No. 022

Dhingra, S. and Machin, S. 2020. The crisis and job guarantees in urban India. CEP Discussion Paper No 1719

Dhingra, S. and F. Kondirolli. 2022. Unemployment and labour market recovery policies. Indian Economic Review 57(1): 223–235.

Drèze, J. and Somanchi, A. 2021. The COVID-19 crisis and people's right to food. SocArXiv, 1 June 2021. Web.

Drèze, J. 2020. An Indian DUET for urban jobs. Bloomberg Quint Opinion.

Eliason, M. and D. Storrie. 2009. Does job loss shorten life? Journal of Human Resources 44(2): 277–302.

Elsby, M.W.L., R. Michaels and G. Solon. 2009. The ins and outs of cyclical unemployment. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1(1): 84–110.

Elsby, M., B. Hobjin and A. Sahin. 2013. Unemployment dynamics in the OECD. Review of Economics and Statistics 95(2): 530–548.

Eriksson, T. and N. Kristensen. 2014. Wages or fringes? Some evidence on trade-offs and sorting. Journal of Labor Economics 32(4): 899–928.

Ferreira, F. 2021. Inequality in the time of COVID-19. Finance and Development, 58(2): 20–23.

Gupta, A., Malani, A. and Woda, B. 2021. Explaining the Income and Consumption Effects of Covid in India (No. w28935). National Bureau of Economic Research

Gupta, M. and A. Kishore. 2022. Unemployment and household spending in rural and urban India: evidence from panel data. The Journal of Development Studies 58(3): 545–560.

Hussam, R., E.M. Kelley, G. Lane and F. Zahra. 2022. The psychosocial value of employment: evidence from a refugee camp. American Economic Review 112(11): 3694–3724.

ILO 2020. The role of public employment programmes and employment guarantee schemes in COVID-19 Policy Responses, Development and Investment Branch. ILO Brief.

ILO 2021a. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 8th Edition.

ILO 2021b. ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. 10th Edition.

ILO 2023. World employment and social outlook: Trends 2023.

Jacobson, L., R. LaLonde and D. Sullivan. 1993. Earnings losses of displaced workers. American Economic Review 83(4): 685–709.

Khamis, M., Prinz, D., Newhouse, D., Palacios-Lopez, A., Pape, U. and Weber, M. 2021. The early labor market impacts of COVID-19 in developing countries. Policy Research Working Paper No. 9510. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Kuziemko, I., M. Norton, E. Saez and S. Stancheva. 2015. How elastic are preferences for redistribution? Evidence from randomized survey experiments. American Economic Review 105(4): 1478–1508.

Landry, C.E. and J.A. List. 2007. Using ex ante approaches to obtain credible signals for value in contingent markets: evidence from the field. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 89(2): 420–429.

Loomis, J. 2011. What’s to know about hypothetical bias in stated preference valuation studies? Journal of Economic Surveys 25(2): 363–370.

Machin, S. and A. Manning. 1999. The causes and consequences of long-term unemployment in Europe. In Handbook of Labor Economics, ed. O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, vol. 3. North Holland Press.

Mas, A. and A. Pallais. 2017. Valuing alternative work arrangements. American Economic Review 107(12): 3722–3759.

NSO 2018. Periodic Labor Force Survey Annual Report. MOSPI, Government of India.

NSO 2019. Periodic Labor Force Survey Annual Report. MOSPI, Government of India.

NSO 2020. Periodic Labor Force Survey Annual Report. MOSPI, Government of India.

OECD. 2020. OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Ohnsorge, F. and Yu, S., eds. 2021. The long shadow of informality: challenges and policies. Advanced Edition.

Petrongolo, B. and C. Pissarides. 2008. The ins and outs of European unemployment. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 98(2): 256–262.

Ray, D. and Subramanian, S. 2020. India's lockdown: an interim report. Indian Economic Review August 19: 1–49.

Ruhm, C.J. 1991. Are workers permanently scarred by job displacement? American Economic Review 81(1): 319–324.

Shimer, R. 2012. Reassessing the ins and outs of unemployment. Review of Economic Dynamics 15(2): 127–148.

Sinha Roy, S. and Van Der Weide, R. 2022. Poverty in India has declined over the last decade but not as much as previously thought. Policy Research Working Paper No. 9994. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Somanchi, A. and Dreze, J. 2021. New barometer of India's economy fails to reflect deprivations of poor households. Economic Times, June 2021.

Somanchi, A. 2021. Missing the poor, big time: a critical assessment of the consumer pyramids household survey.

Stantcheva, S. 2020. Understanding economic policies: what do people know and learn?. Harvard University Working Paper.

Sullivan, D. and T. von Wachter. 2009. Job displacement and mortality: an analysis using administrative data. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(3): 1265–1306.

Von Wachter, T. 2020. The persistent effects of initial labor market conditions for young adults and their sources. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34: 168–194.

Wiswall, M. and B. Zafar. 2018. Preference for the workplace, investment in human capital, and gender. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(1): 457–507.

World Bank 2022. Poverty and shared prosperity 2022: correcting course. The World Bank

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the ERC Starting Grant 760037 is gratefully acknowledged. The primary survey was reviewed and approved by the LSE Research Ethics Committee (REC Ref. 1129) and conducted by Sunai. We are grateful to Stephen Machin and Uday Bhanu Sinha for their comments. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.