Abstract

What is the role for supply and demand forces in determining movements in international banking flows? And what role might a common factor—the global financial cycle highlighted by Rey (Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence, 2018) and others—play in movements in these flows? Answering these questions is crucial for understanding the international transmission of financial shocks and formulating policy. This paper addresses them by using the method developed in Amiti and Weinstein (J Polit Econ 126(2):525–587, 2018) to exactly decompose the growth in international bank credit into common shocks, idiosyncratic supply shocks and idiosyncratic demand shocks for the period 2000–2017. A striking feature of the global banking flows data can be characterized by what we term the “Anna Karenina Principle”: all healthy credit relationships are alike, and each unhealthy credit relationship is unhealthy in its own way. During non-crisis years, bank flows are well explained by a common global factor. But during times of crisis, flows are affected by idiosyncratic demand shocks to borrower countries and by supply shocks to their creditor banks. That is, the importance of the common component seems to vary over time. This has important implications for why standard econometric models break down during crises.

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis)

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: Bloomberg, SNL Financial; BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the terms “supply” and “demand” are defined in terms of factors that are explainable by a credit supplier-time fixed effect and a borrower-time fixed effect, respectively. Thus, if all banking systems cease lending to a particular country, we will call that a demand shock because it is explainable by some characteristic of that destination even though the reason might be that all banking systems refuse to lend to that borrower. This approach has strong parallels in the literature aiming to identify a global factor or “push” and “pull” factors (e.g., Fernandez-Arias 1996). Our common shock captures the net impact of global factors that cause either all lenders to change their lending behaviour or all borrowers to change their demand for funds. Similarly, our idiosyncratic supply and demand shocks capture push and pull factors that are not common to all countries. However, since we cannot identify how much of a given percentage change in borrowing that affected all borrowers was due to all lenders changing their behaviour and how much was due to all borrowers changing theirs, we will maintain the nomenclature of “common,” “idiosyncratic supply” and “idiosyncratic demand” shocks, rather than global factor, push and pull.

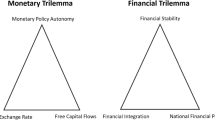

Rey (2018) argues that since the global financial cycle is not necessarily aligned with a country’s specific macroeconomic conditions, the policy “trilemma” that a country faces—namely that free capital mobility and independent monetary policy are feasible only with floating exchange rates—is really a “dilemma”—independent monetary policy is possible if and only if the capital account is managed.

Forbes and Warnock (2012) also examine surges and stops in capital flows in relation to movements in the VIX.

Khwaja and Mian (2008) derive a version of this equation from a structural model in which banks face positive marginal financing costs and decreasing returns to capital as aggregate borrowing increases.

In Amiti and Weinstein (2018), Proposition 2 states “WLS estimation of Eq. (1) with [lagged lending] weights will produce estimates of bank and firm shocks whose loan-weighted average will exactly match the bank, firm, and economywide loan growth rates of loan relationships that existed in t − 1. No other estimates of bank and firm shocks will satisfy this condition”. If we replace the words “bank,” “firm” and “economywide,” with the words “banking-system,” “borrowing-country” and “global,” this proposition can be applied to our data. The fact that OLS estimates cannot be aggregated using lagged lending weights to match borrower or banking system loan growth rates follows directly from the second sentence in the proposition. The intuition follows from the fact that WLS estimates are uniquely identified in matching the aggregate borrower, lender and global growth rate moments, so no other estimates of borrower and banking-system fixed effects (including OLS) can have this property.

Coefficients estimated with OLS are unbiased for the subset of existing bilateral claims, but often what is of interest is the behaviour of aggregate credit growth. Thus, in data samples where bilateral links regularly disappear and reappear, simple OLS is of little use.

Proposition 1 in Amiti and Weinstein (2018) proves that in a linear loan growth model with an interaction term, weighted least squares (WLS) estimation produces identical estimates of the supply and demand shocks as long as the components of the interaction term that vary only at the bank or firm level are defined to be part of the bank and firm shocks. The intuition for why this is true follows from our definition of interactions as the orthogonal component of any ij shock. This is a necessary normalization as any interactive shock, αij, associated with one set of demand and supply shocks (\(\alpha_{it} ,\beta_{jt}\)), can always be redefined to be a different interactive shock (αij + δi + δj) that is associated with different demand and supply parameters (\(\alpha_{it} - \delta_{ji} ,\beta_{jt} - \delta_{j}\)). The obvious normalization to avoid this problem is to define interaction term as the component of αij that is orthogonal to the demand and supply shocks. However, this normalization means that the inclusion of the interaction term cannot affect the fixed effects because they are orthogonal to the demand and supply shocks by construction.

We use the CBS on an immediate counterparty basis (IC basis), which allocates claims to the country and sector where the contractual counterparty is located. These statistics are appropriate for analysing the credit provided to particular countries. By contrast, the CBS on an ultimate risk basis (UR basis) allocates claims to the country and sector where the ultimate obligor resides, that is, after taking into account parent- and third-party guarantees, CDS protection bought, collateral and other credit hedges.

Claims do not include derivatives with a positive market value (from the reporting bank’s perspective) with a contractual counterparty in the country. These are reported separately in the CBS (UR basis).

Banks’ claims on their home country have been included in the CBS only since 2013 Q4 and are thus not considered in this paper.

See Cerutti (2015) for a separate consideration of the role of branches and subsidiaries in the CBS.

FC = INTLC + LCLC where INTLC = cross-border claims (XBC) plus locally extended claims in non-local (foreign) currencies (LCFC).

For example, in 2005, Unicredit, an Italian bank, bought HypoVereinsbank (HVB), a German bank. As a result, all foreign claims booked by the latter disappeared from German banks’ consolidated foreign claims and appeared in Italian banks’ claims. A similar issue arose in 2009 Q1 when four US investment banks were converted to depository institutions and thus included for the first time in the population of US banks reporting in the CBS (see Avdjiev and Upper 2010 for discussion).

The CBS provide only a partial breakdown by currency. Specifically, the currency of denomination for LCLC is known by construction. By contrast, that for INTLC is not known. To adjust INTLC for exchange rate movements, we use the information about the currency of denomination in the BIS Locational Banking Statistics, as described in “Appendix 2”.

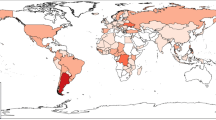

For a list of the countries classified as advanced economies, emerging economies and offshore financial centres in Fig. 1 and throughout the paper, see “BIS locational banking statistics: explanation of the data structure definitions” on the BIS website.

The breaks-in-series adjustment (dashed black lines) appears to contribute less when viewed at the aggregate level (top left-hand panel). However, where breaks do occur, they tend to have a larger effect at the bilateral level than do exchange rate movements.

If there were no systematic measurement error in the unadjusted line, the coefficient should be one. The R-squared from this regression is 89%, and the coefficient on the adjusted series is statistically significant at the 99th percentile, with a t-statistics of 22.1.

Wholesale funding, broadly defined, is any funding liability other than funding received from an individual person (i.e. retail deposits). During the crisis, numerous forms of wholesale funding—interbank borrowing, funding from money market funds (MMF), and deposits of foreign exchange reserves—became increasingly expensive or dried up completely.

Even if restricted to claims on emerging economies only, the sample is still concentrated: 14% of the resulting 2727 observations at end-Q4 2017 captured 95% of foreign claims on all of them.

This reflects the fact that foreign claims, in particular their cross-border component, are not atomistic. For example, Cerutti et al (2015) report that the average deal size for syndicated loans, which constitute a substantial portion of claims in the CBS, fluctuated around $400 million between 2000 and 2012 for borrowers in advanced economies; for those in emerging economies, average deal size rose from roughly $200 million in 2000 to $300 million in 2007. The discrete nature of claims means that the booking of a new loan, or the maturation of an old loan, generate significant jumps in total outstanding positions when claims stocks are small. By weighting observations, the empirical methodology outlined in Sect. 2 and applied in Sect. 4 tackles this problem head on.

These growth rates have been adjusted for breaks in series and exchange rate movements as described in Sect. 4 above.

In what follows, we exclude banks headquartered in Brazil, Greece, Ireland, Mexico and Norway due to data quality issues.

Japanese banks did register a series of large negative idiosyncratic supply shocks in the early 2000s, when many were on the verge of collapse and under regulatory scrutiny.

This reflected Spanish banks’ reliance on local lending funded by local liabilities in their many host countries across Latin America, which had the effect of insulating them from the disruptions in the funding market in their home country and elsewhere (McGuire and von Peter 2016).

The difference in the time period in this figure is due to data availability. Banks did not disclose loss data prior to 2008. Loss data are available for only those banking systems shown in the left panel of Fig. 9. For each reporting banking system, we assemble the data for the top internationally active banks headquartered in each country and match these with the list of reporting banks for those countries provided to the BIS by each reporting jurisdiction.

Amiti and Weinstein (2011) use Japanese data to show that in crisis periods banks cut their short-term claims relative to their long-term ones.

International claims (INTLC) are broken down into three maturity buckets (remaining maturity of less than 1 year, less than 2 years but more than 1 year, and over 2 years). No maturity breakdown is available for local claims in local currencies and thus not for total foreign claims (FC). As a result, the ratio used in the right panel of Fig. 9 is a lower bound estimate of each banking system’s share of foreign claims that are short term.

We also examined the impact of excluding banks’ foreign claims on the official sector in countries where the central bank engaged in QE operations, so that we can focus on private borrowers. When non-US banks’ claims on the US official sector are excluded, the post-crisis demand shocks for the USA are slightly more negative than otherwise. In examining the full set of results (i.e. for other countries with QE operations, e.g. Japan, the euro area and the UK), a similar but smaller effect is evident. In most cases, however, the difference in the average estimated demand shocks using total and private borrowing was not statistically significant.

The contraction in foreign claims on the UK was amongst the most severe (− 22%), reflecting the fact that London is a financial hub for both banks and non-bank financial institutions. Short-term cross-border interbank lending to banks in the UK in particular dropped sharply and has yet to recover.

The y-axes in Fig. 12 show the minimum value of the shock measures (i.e. the smallest positive or the largest negative values) during the crisis window.

In many countries, a portion of banks’ local claims in local currencies are funded by cross-border inter-office positions, or by non-local currencies raised either locally or offshore. By focusing on the local intermediation share, which captures only those local claims that have local currency funding, we arguably better capture the most insulated portions of creditor banks’ balance sheets. See McCauley et al. (2012) for more discussion. Formally, LINT is defined as the ratio of the minimum of local claims in local currencies and local liabilities in local currencies summed across creditor banking systems b to total foreign claims on the country, or:

\({\text{LINT}}_{c,t} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{\varvec{b}} {\mathbf{min}}\left( {{\mathbf{LCLC}}_{{\varvec{b},\varvec{c},\varvec{t},}} ,{\mathbf{LLLC}}_{{\varvec{b},\varvec{c},\varvec{t},}} } \right)}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{\varvec{b}} {\mathbf{FC}}_{{\varvec{b},\varvec{c},\varvec{t}}} }}.\)

The relationship is statistically significant (at the 95% level), and the slope of the regression line indicates that a ten percentage point higher local intermediation share on the eve of the crisis is associated with a maximum negative demand shock that was 1.8 percentage points smaller (i.e. less severe) during the crisis window.

For example, in the LBSN, the reporting country UK reports LCFC with a currency breakdown separately for the German banks, Swiss banks, French banks, etc., that are located there.

By definition, LCFC does not include positions denominated in the domestic currency of the counterparty country. Thus, in applying the currency distribution taken from cross-border claims on that country as described (c), the domestic currency of that country is excluded.

That is, they reveal, for example, the currency composition of the cross-border claims of German banks in the UK, and that of cross-border claims of German banks in every other reporting location. These can be aggregated to reveal the currency composition of German banks’ total cross-border claims booked in all locations. But the information about the counterparty country was introduced in the LBSN only in 2013. Thus, they do not reveal the currency distribution of German banks’ worldwide consolidated claims on counterparties in any one particular country.

References

Amiti, M., and D. Weinstein. 2011. Exports and Financial Shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(4): 1841–1877.

Amiti, M., and D. Weinstein. 2018. How Much do Bank Shocks Affect Investment? Evidence from Matched Bank-Firm Loan Data. Journal of Political Economy 126(2): 525–587.

Alfaro, L., S. Kalemli-Ozcan, and V. Volosovych. 2008. Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries? An Empirical Investigation. The Review of Economics and Statistics 90(2): 347–368.

Avdjiev, S., L. Gamacorta, L. Goldberg, and S. Schiaffi. 2017. The Shifting Drivers of Global Liquidity. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report, No. 819.

Avdjiev, S., Z. Kuti and E. Takáts. 2012. The Euro Area Crisis and Cross-Border Bank Lending to Emerging Markets. BIS Quarterly Review, December.

Avdjiev, S., and E. Takáts. 2014. Cross-Border Bank Lending During the Taper Tantrum: The Role of Emerging Market Fundamentals. BIS Quarterly Review, September.

Avdjiev, S., and C. Upper. 2010. Impact of the Reclassification of US Investment Banks. BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Baba, N., R. McCauley and S. Ramaswamy. 2009. US Dollar Money Market Funds and Non-US Banks. BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Bruno, V., and H.S. Shin. 2014. Cross-Border Banking and Global Liquidity. The Review of Economic Studies 82(2): 535–564.

Bruno, V., and H.S. Shin. 2015. Capital Flows and the Risk Taking Channel of Monetary Policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 71(3): 119–132.

Buch, C. 2003. What Drives the International Activities of Commercial Banks? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 35(6): 851–861.

Cerutti, E. 2015. Drivers of Cross-Border Banking Exposures During the Crisis. Journal of Banking & Finance 55: 340–357.

Cerutti, E., S. Claessens, and L. Ratnovski. 2017a. Global Liquidity and Cross-Border Bank Flows. Economic Policy 32(89): 81–125.

Cerutti, E., S, Claessens and A. Rose. 2017b. How Important is the Global Financial Cycle? Evidence from Capital Flows. IMF Working Paper WP/17/193.

Cerutti, E., G. Hale, and C. Minoiu. 2015. Financial Crises and the Composition of Cross-Border Lending. Journal of International Money and Finance 52: 60–81.

Cetorelli, N., and L. Goldberg. 2011. Global Banks and International Shock Transmission: Evidence from the Crisis. IMF Economic Review 59(1): 41–76.

Eaton, J., S. Kortum, and F. Kramarz. 2004. Dissecting Trade: Firms, Industries, and Export Destinations. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 94(2): 150–154.

Fernandez-Arias, Eduardo. 1996. The New Wave of Private Capital Inflows: Push or Pull? Journal of Development Economics 48(1996): 389–418.

Forbes, K., and F. Warnock. 2012. Capital Flow Waves: Surges, Stops, Flight and Retrenchment. Journal of International Economics 88: 235–251.

Fratzscher, M. 2012. Capital Flows, Push Versus Pull Factors and Global Financial Crisis. Journal of International Economics 88: 341–356.

Goldberg, L., and S. Krogstrup. 2018. International Capital Flow Pressures. NBER Working Paper 24286.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., E. Papaioannou, and P. Fabrizio. 2013. Global Banks and Crisis Transmission. Journal of International Economics 89(2): 495–510.

Khwaja, A., and A. Mian. 2008. Tracing the Impact of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from an Emerging Market. American Economic Review 98(4): 1413–1442.

Koepke, R. 2015. What drives capital flows to emerging markets? A survey of the empirical literature. Institute of International Finance Working Paper.

Lane, P., and G.M. Milesi-Ferretti. 2012. External Adjustment and the Global Crisis. Journal of International Economics 88(2): 252–265.

Lane, P., and G.M. Milesi-Ferretti. 2014. Global Imbalances and External Adjustment After the Crisis. IMF Working Paper WP/14/151.

Laeven, L., and F. Valencia. 2013. Systemic Banking Crises Database. IMF Economic Review 61(2): 225–270.

McCauley, R., P. McGuire and G. von Peter. 2012. After the Global Financial Crisis: From International to Multinational Banking? Journal of Economics and Business 64(1): 7–23. Based on The architecture of global banking: from international to multinational? BIS Quarterly Review, March 2010.

McGuire, P., and N. Tarashev. 2008. Bank Health and Lending to Emerging Markets. BIS Quarterly Review, December.

McGuire, P., and G. von Peter. 2012. The US Dollar Shortage in Global Banking and the International Policy Response. International Finance, June 2012. Also published as BIS Working Papers no 291.

McGuire, P., and G. von Peter. 2016. The Resilience of Banks’ International Operations. BIS Quarterly Review, March 2016.

McGuire, P., and P. Wooldridge. 2005. The BIS consolidated banking statistics: structure, uses and recent enhancements. BIS Quarterly Review, September.

Milesi-Ferretti, G.M., and C. Tille. 2011. The Great Retrenchment: International Capital Flows During the Global Financial Crisis. Economic Policy 26: 289–346.

Miranda-Agrippino, S., and H. Rey. 2018. US Monetary Policy and the Global Financial Cycle. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21722, February.

Papaioannou, E. 2009. What Drives International Financial Flows? Politics, Institutions and Other Determinants. Journal of Development Economics 88(2): 269–281.

Peek, J., and E. Rosengren. 1997. The International Transmission of Financial Shocks: The Case of Japan. American Economic Review 87(4): 495–505.

Rey, H. 2018. Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 21162, February.

Takáts, E. 2010. Was it Credit Supply? Cross-Border Bank Lending to Emerging Market Economies During The Financial Crisis. BIS Quarterly Review, June.

Wu, J.C., and F.D. Xia. 2016. Measuring the Macroeconomic Impact of Monetary Policy at the Zero Lower Bound. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 48(3): 253–291.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jakub Demski and Scott Marchi for excellent research assistance and thank Mark Carlson, Linda Goldberg, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Catherine Koch, Bruno Tissot, Philip Wooldridge, participants at the 3rd BIS-CGFS workshop on “Research on global financial stability: the use of the BIS international and financial statistics” (7 May 2016), participants at the BIS-Bank Negara Malaysia conference on “Financial Systems and the Real Economy (18–19 October 2016, Kuala Lumpur), seminar participants at De Nederlandsche Bank (20 September 2016) and three anonymous referees for comments and discussion. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the BIS, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Deriving the common shock

Amiti and Weinstein (2018) show in Proposition 4 that one can obtain estimates of C country borrower and B banking-system shocks that satisfy

This can be written more compactly as:

and

where

and

and the parameter estimates that would solve this new system. We can renormalize the system by expressing each shock relative to the median borrowing-country or banking-system shock. Specifically, we define the common borrower shock, \(\varvec{ }\bar{A}_{t}\), as the median borrower shock, and the common banking-system shock as the median banking-system shock, \(\varvec{ }\bar{B}_{t}\). We next define the borrowing-country shock as the difference between the actual shocks and the median shock, i.e. \(\dot{\varvec{A}}_{\varvec{t}} \equiv \varvec{A}_{t} - \bar{A}_{t} 1_{C}\) and \(\dot{\varvec{B}}_{\varvec{t}} \equiv \varvec{B}_{t} - \bar{B}_{t} 1_{B}\). We can rewrite the system of equations as

where we move from the second line to the third line by making use of the fact that the borrowing shares from each financial institution (\({\varvec{\Theta}}_{t - 1}\)) must sum to one, i.e. \({\varvec{\Theta}}_{t - 1} 1_{B} = 1_{C}\) and define the common shock to be \(\hat{c}_{t} \equiv \varvec{ }\bar{A}_{t} + \varvec{ }\bar{B}_{t}\). Just as we can decompose firm borrowing into these three shocks, we can also decompose bank lending into a similar set of three elements. Similarly, we can rewrite Eq. (A1) as

Appendix 2: Adjustments to Foreign Claims

2.1 Breaks-in-Series

Breaks-in-series caused, for example, by bank mergers or methodological changes lead to jumps in bilateral positions that do not signify that extension or withdrawal of actual credit. Fortunately, the distortions caused by many of the largest of the breaks can be corrected. Reporting countries often provide to the BIS, on a confidential basis, “pre-break” values of outstanding claims from which adjusted bilateral growth rates can be constructed. Where available, we have used these pre-break values in calculating the year-over-year changes in outstanding bilateral claims amounts, which are used as inputs in the empirical analysis.

When there is a known break-in-series, but the pre-break data are not available (i.e. not provided by the reporting jurisdiction), we have two choices: either truncate the sample for the affected banking system, so that the series starts in the quarter after the break; or assume the pre-break growth rates are zero. A priori, it is not clear which procedure is better. Truncating the series has no effect on the estimated shocks in later periods. But the aggregate growth rates (and hence the estimated common and demand-side shocks) prior to the break date are necessarily affected since some observations have been excluded. By the same token, retaining the full series for these banking systems and simply assuming that the growth in claims in the quarter in which the break occurred is zero also introduces error into the estimated shocks. In practice, however, the difference between these approaches is small. In what is presented in the paper, we have truncated the series for certain banking systems where breaks occurred.

For one observation for which break-in-series values were not available, we estimated the break value from information in the underlying bilateral positions. For another that reflected the purchase of a subsidiary bank in a particular country, we assumed that the break value was simply full change in the outstanding claim amount.

2.2 Exchange Rate Movements

Foreign claims on a particular borrower country tend to be denominated in a mixture of currencies. Changes in the relative value of these currencies induce changes in the outstanding stock of claims when expressed in any single currency, here in US dollars. Changes in exchange rates may have economic meaning from the perspective of a reporting banking system, for example in analyses of how currency mismatches across the balance sheet affect bank profitability. However, they are not indicative of the provision or retraction of actual credit, which is the metric needed for the empirical analysis in this paper. In most quarters, exchange rate movements contribute little to the growth in aggregate foreign claims. But, as shown in the main text, extreme exchange rate movements, like those that occurred in the months following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, significantly distort measures of the growth in foreign claims.

The first step in the adjustment is to obtain measures of the share of each currency in foreign claims. Foreign claims can be broken into three pieces: (a) cross-border claims (XBC), (b) local claims in foreign (i.e. non-local) currencies (LCFC) and (c) local claims in local currencies (LCLC). That is, FC = XBC + LCFC + LCLC. In the CBS, XBC and LCFC are reported together as international claims (INTLC = XBC + LCFC), although these claims can be separated (albeit imperfectly) using the BIS Locational Banking Statistics, which has a currency breakdown. We obtain the currency shares for each of these three components separately and then use them to obtain the shares of each currency in total foreign claims.

The currency shares for these three pieces are obtained as follows:

(a) LCLC: The currency of denomination of LCLC is known by construction. It is simply the currency in use in the borrower country.

(b) LCFC: For many banking-system borrower pairs, the currency shares for LCFC are also known, from the BIS Locational Banking Statistics by Nationality (LBSN). Unlike the CBS, the LBSN track the cross-border claims and local claims in non-local currencies (LCFC) of banks located in a particular location, broken down by the nationality of the banking system.Footnote 37 Thus, for any country that reports the LBSN to the BIS, we know the currency breakdown (USD, EUR, JPY and other foreign currencies) for each national banking systems’ LCFC on the residents of that reporting country.

Currently, more than 40 countries report the LBSN to the BIS, covering more than 95% of each consolidated national banking systems’ global foreign claims. But there are only a few emerging economies that report the LBSN (Brazil, Chile Mexico, South Africa, Chinese Taipei, India, Indonesia, Malaysia and South Korea), and several of them only started reporting after 2000. We do not have actual data about the currency composition of each banking systems’ LCFC vis-à-vis those countries that do not report in the LBSN (e.g. China, Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland). For these countries, we assume that the composition of each banking systems’ LCFC is the same as that for all cross-border claims on that country, as described in (c) below.Footnote 38

(c) XBC: Obtaining the currency shares for a consolidated national banking system’s cross-border claims on a particular country is the most problematic. The LBSN provide information about the currency composition of banks’ cross-border claims booked by their offices in each reporting location. But, critically, they do not reveal the location (country) of the borrower.Footnote 39 The BIS Locational Statistics by Residency (LBSR), by contrast, track the cross-border claims booked by banks offices in each reporting country on individual borrower countries, broken down by currency. But, the LBSR, unlike the LBSN, do not reveal the nationality of the banking system located in each reporting country. In addition, cross-border claims in the LBSR include banks’ interoffice positions, which are not included in the CBS and thus not in foreign claims. Cross-border claims in the LBSR are broken down into positions denominated in USD, EUR, JPY, GBP, CHF, the domestic currency of the borrower country, and “Other” foreign currencies.

To obtain the currency shares of each national banking system’s worldwide consolidated cross-border claims on a particular country, we take the shares reported in the LBSR for banks of all nationalities and apply these to banks of each nationality. That is, the currency shares of US banks’ cross-border claims on Hungary are assumed to be the same as the shares of German, Swiss and other banks’ claims on Hungary. For those borrower countries that themselves report the LBSN to the BIS, we make an additional correction to exclude interoffice positions in each currency. Specifically, for these countries, we obtain the currency distribution by taking cross-border claims of all banks in all other BIS reporting countries on all sectors in the borrower country and subtract from this the total cross-border interoffice liabilities reported by banks (of all nationalities) located in the borrower country.

For those borrower countries that do not report the LBSN, we assume that the currency composition of the total international claims in the CBS (INTLC = XBC + LCFC) is simply equal to the currency composition of total cross-border claims (including interoffice) from the LBSR.

With the currency shares for the three components of foreign claims in hand, we are able to estimate the overall currency shares for each consolidated banking system’s total foreign claims on each borrower country. The second step in our adjustment is to feed these data series, along with exchange rates, into a chain-linked adjustment that yields the year-over-year growth in foreign claims excluding the effect of exchange rate movements.

Appendix 3: Estimated shocks and the maturity of claims

The estimated supply and demand shocks are heterogeneous across borrower countries. One reason for this is that foreign claims differ across countries in terms of the counterparty sector, maturity and instrument, all of which affect the ease with which creditor banks can adjust their balance sheets. For example, banks can more quickly cut back on short-term interbank loans by simply not rolling them over. Similarly, they can quickly sell high-quality liquid securities. But longer-term loans and illiquid securities are far more difficult to take off the balance sheet.

Estimation of the shocks based on bilateral foreign claims does not take these claim characteristics into account. Yet the combination of instrument, maturity and counterparty type for a particular borrower country clearly has an impact on the estimated shocks, as discussed in Sect. 5.4.2. Borrower countries where a high share of the claims in 2007 was short-term or interbank experienced larger contractions in the growth of overall foreign claims. These outsized contractions mean that the common shock accounts for less of the overall change in the growth rate, leaving the estimated demand and supply-side shocks to absorb the remaining part. This has bearing on how the estimated shocks should be interpreted, as discussed below.

Table 4 provides some concrete examples of where these differences come into play. Column 2 lists all banks’ combined foreign claims at end-Q2 2007 on the country listed in the first column. The breakdown by remaining maturity is available only for international claims (column 3); no such information is available for banks’ local claims in local currencies. As such, short-term international claims (column 4) provide a lower-bound estimate of the share of short-term claims in total foreign claims (column 5). More than 80% of the claims on China were international claims (column 5), meaning banks’ had a relatively small local presence there. And more than half of these had a remaining maturity of one year or less (column 7). As a result, short-term claims comprised at least 44% of the total foreign claims on China (column 6), and the highest share for all the countries is listed in Table 4. Only claims on Caribbean offshore centres, virtually all of which were international, had an estimated share close to China’s (39%). By contrast, the estimated shares for Latin America (15%) and Emerging Europe (24%) were considerably lower. These differences across regions help explain the heterogeneous growth in foreign claims in Fig. 3 in the main text.

These differences have implications for the interpretation of the shocks. To see this, the left panel of Fig. 13 shows a comparison of the common shock estimated for foreign claims (red line) and for short-term international claims only (gold line). Focusing only on short-term claims greatly reduces the outstanding claim amounts, but also reduces the heterogeneity across countries in the flexibility of the claims. With this heterogeneity removed, the dynamics of short-term claims are more likely to be driven by common shocks than by idiosyncratic supply and demand shocks. During the 2007–2009 crisis period, this indeed seemed to be the case: the common shock estimated with short-term claims moved farther into negative territory (− 10%) than that estimated with foreign claims.

Sources: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Shock estimates for foreign claims and short-term international claims. Notes: The solid vertical lines indicate the crisis window (end-Q2 2007 to end-Q4 2009). The dashed vertical line indicates end-Q3 2008, just after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. 1The lines show the estimated common shock based on the year-over-year growth in foreign claims (FC, red line) and in short-term international claims only (ST INTL, gold line). 2Shock estimates based on the year-over-year growth in ST INTL.

That said, for individual countries, the broad patterns in the demand shocks evident in the figures in the main text are not all that different when estimated with short-term international claims only. The centre and right panels of Fig. 13 show the complete set of estimated shocks for China and Hungary. A comparison of these panels to their counterparts in Fig. 11 shows that short-term claims contracted more (black lines) during the 2007–2009 financial crisis (for China) and during the European sovereign crisis (for Hungary) than did foreign claims. However, the overall patterns are remarkably similar, which suggests that the demand shocks we estimate pick up the movements in short-term claims.

Appendix 4: Estimated Shocks for Additional Banking Systems

Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics (IC basis); BIS locational banking statistics; national data; authors’ calculations

Shocks to selected banking systems. Notes: The solid vertical lines indicate the crisis window (end-Q2 2007 to end-Q4 2009). The dashed vertical line indicates end-Q3 2008, just after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. 1Year-on-year growth in foreign claims of internationally active banks of the nationality indicated in the panel title, adjusted for breaks-in-series and exchange rate movements. 2Estimated net demand shocks to the borrower countries on which the banking system in the panel title has outstanding foreign claims. 3Estimated supply shocks that are unique to banking system in the panel title. 4Estimated shocks that are common to all banking systems and borrower countries.