Abstract

Success in the competition for external grants has become an important indicator when progressing in academic careers. Drawing on interview data with academics across various career stages and academic fields at one Finnish university, the study identifies four discourses that elucidate why research grants are deemed significant in advancing an academic career. The findings indicate that it is appealing for universities to use research funding success as an assessment criterion due to its connections to authoritative discourses in higher education and research policy. For example, funding success is seen as a symbol of high academic quality and as a signal of an individual’s ability to thrive in a resource-scarce environment. However, in the context of limited resources for research and the introduction of new societally oriented funding instruments, utilizing funding success as an assessment criterion overlooks academics’ different prerequisites for gaining funding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acquisition of research funding has become an important indicator when progressing in academic careers (Bloch et al. 2014; Pontika et al. 2022; Rice et al. 2020; Saenen et al. 2019). The topic of research assessment is particularly pertinent as research assessment systems face pressures for change, exemplified by the establishment of the Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA) in 2022. In the higher education literature, the emphasis on external research grants has been perceived as an illustration of universities and academics engaging with the market. Approached from the perspective of academic capitalism (Slaughter and Leslie 1997), the market orientation challenges traditional notions of equity in higher education and research systems. While the economic perspective is highly relevant when studying external research grants and their implications in academia, this paper widens the perspective and elaborates on the multiple grounds why research grants have become important in academic career progression.

Academia today is influenced by competitive settings and the necessity to perform in pluralistic environments. Various actors, including university managers, policymakers, and stakeholders, exert demands on both university organizations and individual academics. These diverse expectations are reflected in universities’ academic recruitment and promotion criteria (Pietilä and Pinheiro 2021). This paper argues that using research grants as an assessment criterion is appealing to universities because success in research grants simultaneously mobilizes multiple authoritative discourses within higher education and research.

This study aims to elucidate the factors contributing to the significance of research grants in the progression in academic careers. Utilizing interview data gathered at one university in Finland, the study aims to first identify the main discourses embraced by teaching and research staff (referred to as ‘academics’) in relation to the use of external research grants in the assessment of scholarly performance, especially within the context of academic recruitment and promotion. Second, as the discourses do not operate independently, the study sheds light on the interlinkages between them. The interviewed academics occupied different positions in academic career trajectories, with academic leaders in management positions possessing more formal authority to shape the dominant discourses. Third, the study investigates whether individuals at different levels of the academic hierarchy draw upon different discourses.

The empirical data of the study are based on interviews conducted at one Finnish research-intensive university. The context offers a fruitful arena for the research, given that research funding in the Finnish higher education sector is predominantly driven by competition. The interviews, which addressed a broader theme of researcher assessment in academic recruitment and promotion processes, involved academics at different career stages and from various academic fields. External research grants came up consistently as a key assessment criterion in these interviews. While competitive external grants were acknowledged as a significant assessment criterion, they also evoked diverse reactions, ranging from acceptance and irony to irritation. Thus, in addition to elucidating the reasons external research grants have gained importance in assessing academic performance in Finland, the study also sheds light on academics’ mixed reactions to this criterion. While the empirical data of the study were drawn from a specific northern European country, the identified discourses reflect broader macrodiscourses in higher education and research, transcending the local settings that underpin them.

The study contributes to several scholarly discussions. Firstly, it contributes to studies on the transformations in higher education and research policy, with a particular focus on changes in research funding and their implications at the micro level within universities. The focus on external funds has the potential to alter internal dynamics and social relations within a university, including considerations of worth, prestige, and visibility, and may have long-term consequences for academic collaboration and inclusivity (cf. Polster 2007). Secondly, by examining the discourses employed by academics situated at different career stages and in various academic fields, considering their different potential ‘fundability,’ the study contributes to discussions on social stratification in higher education and research and challenges the perceived neutrality of research funding success as an assessment criterion. Thirdly, the study contributes to the ongoing discussion on reforming research assessment and incentive structures in academic careers.

Competitive External Grants and Evolving Research Assessment

Grant success may have significant effects on academic career progression from an individual standpoint. There are reported positive outcomes of research grants on research productivity. The study by Lee and Bozeman (2005) conducted in the USA found a strong effect of grants on research productivity. Similarly, the study by Habicht et al. (2021) showed that external grants from the German Research Foundation increased the research productivity of male political scientists. Bloch et al. (2014) studied the impact of external grants in the Danish context and found important secondary effects of grants on career advancement via increasing the status and recognition of grant recipients.

Continuous competition may have effects on the work environment and social cohesion within academic settings. The study by Polster (2007) delved into the repercussions of research grants on social relations within the Canadian higher education system. According to her findings, the importance of research grants led universities to invest differently in academic staff and units, favoring those with greater potential for grant productivity. The significance of grants altered the social dynamics between academics and administrators, and recruitment criteria underwent transformation to prioritize individuals with a track record of funding success.

Research funding often follows the Matthew effect, accruing disproportionately to individual academics or research groups (Bol et al. 2018; Zhi and Meng 2016). The Matthew effect refers to cumulative advantages resulting from grant victories. Ylijoki and Ursin (2013)’s analysis highlighted how competitive settings build new polarizations between ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ within the academic community in Finland: those who can survive in the research game (Lucas 2006) and those who cannot. In evaluations, research grant success may be used as a marker for establishing hierarchies between haves and have-nots. Against this background, it is not surprising that research grants elicit diverse reactions among academics. Drawing on Twitter discussions, Olsson’s study (2022) uncovered a spectrum of affects associated with research grants, ranging from joy to anger, and feelings of wasted hours among the applicants.

Universities’ recruitment and performance management systems serve as indicators of the organizational values and contributions prioritized by the institution. Therefore, these systems wield considerable influence in incentivizing certain kinds of behavior among academics (Pietilä 2019). In the realm of academic careers, external grants have gained increasing significance as both recruitment and performance criteria. A study on the evaluation of promotion and tenure in biomedical sciences by Rice et al. (2020) found grant funding to be the second most important criterion after peer-reviewed publications. Based on a survey on research assessment practices at European universities (Saenen et al. 2019), external research grants were identified as important for research careers in nearly all universities. According to the study by Pietilä (2019), funding success held a central position as a recruitment and performance criterion for assistant and associate professors at Finnish universities. Overall, the tenure track systems encouraged academics to prioritize individual career goals over collective objectives.

Similarly, based on their study, Kallio et al. (2016) state that the competitive ethos, underscored by a focus on tangible outputs and metrics, has challenged collegial academic goals within Finnish academia. The narrow use of research metrics has been criticized for pushing academics to focus on individual-centered achievements, such as publishing, instead of focusing on collective tasks, such as mentoring (Moher et al. 2020). The research by Ross-Hellauer et al. (2023) further illustrated that academics perceived that universities placed significant emphasis on the success of grant funding when evaluating the performance of academics. In contrast, academics themselves especially valued collaborative achievements, emphasizing a dichotomy in the assessment priorities between institutions and the academic community.

In recent decades, research assessment systems have come under scrutiny, leading to influential declarations and international agreements (e.g., DORA Declaration 2013; CoARA 2022). Criticism aimed at traditional research-oriented metrics, which prioritize numerical achievements of academics, has prompted calls for global changes in incentives. The growing consensus is to broaden the scope of activities considered when assessing academic contributions.

Finnish R&D Funding System

The Finnish funding system for research and development (R&D) is performance-oriented and competition-based. The core funding for Finnish universities is determined by a funding model. Since 2021, competitive R&D funding obtained has determined 12 percent of the overall funding allocated to universities. Thus, the funding model encourages universities to actively seek additional research funds from external sources. In 2020, external grants composed circa half of all R&D funding at Finnish universities (see Table 1).

External grant sources at Finnish universities are relatively constrained when compared to some international counterparts. The majority of external funding originates from public sources, most notably the Research Council of Finland (formerly known as the Academy of Finland), the innovation-focused Business Finland, the European Union (EU), and other public entities. In 2020, company funding composed circa seven percent of all external funds, and the share has decreased since 2011 (Fig. 1). During the 2010s, the shares of the Research Council of Finland, the EU and various foundations have increased.

Academic fields vary in the commercial relevance of research themes and the target audiences (Ylijoki et al. 2011). These disparities manifest in the diverse array of funding sources available to different fields and the extent to which academics can obtain external grants. Within Finnish universities, the proportion of external grants is large in technology and engineering (external funding comprising 59% of all research funding in 2020), medical and health sciences (56%), and natural sciences (54%) (Vipunen Database). In contrast, humanities and social sciences rely more heavily on block grants, constituting 65% and 62% of their research funding, respectively. The proportion of foundation- and trust-funded research is largest within medical and health sciences (20% of external funding). In addition, foundations are important funding sources especially for early-career researchers (Siekkinen et al. 2021).

In the 2010s, there has been an increase in the proportion of politically directed and thematically focused funding in Finland, as new funding instruments have been introduced. Notably, three funding sources have emerged: the Strategic Research Council, the Flagship Program of the Research Council of Finland, and the Government’s analysis, assessment, and research activities (however, the latter will be discontinued by the conservative Orpo government in 2024). The instruments have distinct focuses. Overall, their introduction may be interpreted as a quest for more informed-based decision-making, an impetus to establish larger inter-disciplinary research consortia, and as an encouragement for academics to select research topics aligned with societal challenges.

At Finnish universities, 52% of teaching and research staff holding a doctoral degree were on fixed-term contract in 2022 (Association of Finnish Independent Education Employers 2023, 3), a high percentage compared to other sectors. The prevalence of fixed-term contracts is frequently justified by the nature of time-limited, project-based funding. From an individual academic's standpoint, funding success is closely intertwined with questions of employment (Olsson 2022).

Data and Method

The research data comprise 23 interviews conducted with academics in 2022. The selection of interviewees aimed to encompass diverse academic fields, career stages (R2–R4), genders, individuals with both Finnish and non-Finnish backgrounds, and those in academic leadership positions within faculties. Among the participants, 13 were in the highest career stage (R4), including professors, research directors, and academic deans. The remaining ten represented career stages R2 and R3, encompassing post-doctoral researchers, senior researchers (including one in tenure track), and university lecturers (for the descriptors of researcher classification, see EURAXESS 2023). Some academics with a non-Finnish background declined the interview request, resulting in only three interviewees with a non-Finnish background, all of whom were post-doctoral researchers. The interviews with academics at career stage R4 were conducted with a colleague. All interviews were conducted online with a video connection. The interviews lasted from 30 min to 2 h. Apart from one interview, all sessions were recorded.

All the academics were affiliated with the same university. This comprehensive university was established after a merger of former universities in 2010. Within the university, the acquisition of research funding is a formal component of the evaluation system for professors. However, lack of success in securing funding may be compensated by demonstrating performance in other aspects of research or teaching.

The research interviews were conducted within the broader framework of researcher assessment. The primary focus was on the criteria that academics deemed relevant when universities recruit individuals for academic positions, and their perspectives on potential changes to existing assessment systems. External research grants were not the central theme in the interview design. Nevertheless, almost all academics acknowledged grants as a central criterion for advancing in academic careers.

In the analysis of the interview data, I used a social constructivist approach that explores how language constructs reality (Fairclough 1992; 2003). Fairclough (2003, 124) perceives discourses as ‘ways of representing aspects of the world—the processes, relations and structures of the material world, the “mental world” of thoughts, feelings, beliefs and so forth, and the social world.’ Studying the different discourses around external research grants in researcher assessment treats assessment systems not as politically neutral, but as sites of struggle; discourses may not only complement each other but also compete with one another (Fairclough 2003). Discursively, the topic of research grants provided rich material as it allowed for diverse interpretations and elicited tension and affective emotions among study participants.

To understand the discourses around external research grants, a consideration of broader macrosocietal discourses underpinning the specific higher education and research system, in this case Finland, was needed. Discourses that draw on other discourses and texts may invoke more broadly grounded understandings and meanings and may thus also have a broader impact (Harley and Hardy 2004, 386). Therefore, acknowledging the connections between local-level discourses and their retrieval of authority from macro-level discourses was relevant.

Methodologically, I identified how interviewees constructed parallel, competing systems of meaning to rationalize the emphasis on research grants in career assessments, particularly in academic recruitment and promotion. While my approach in the analysis was data-driven, it was informed by my knowledge of Finnish and European higher education and research policies and ongoing policy processes in research assessment. Discourse analysis helped in unveiling dominant discourses, often portrayed in the interviews as self-evident, and the more latent discourses. Discourses that legitimize social order—how things are and how things are done (Fairclough 2003, 219)—were in the interviews actively used and supported, but also acknowledged and yet resisted.

In the analysis, I connected the identified discourses to more macro-level societal discourses that underpin the developments in higher education sector. It should be acknowledged that the identification of the discourses, especially the macro-level discourses, has been influenced by my ‘members resources’ (Fairclough 2001): shaped by my cognitive resources as a researcher in academic careers, and Finnish and European research policy.

In the interviews, academics with more work experience contemplated, on average, the significance of research funding in more diverse ways than their junior colleagues. Thus, the analysis somewhat over-emphasizes the perspectives of academics at career stages R3 and R4. Academics in the top hierarchical level, especially the ones with a formal leadership position, often adopted a broader, organizational perspective to the topic. However, in some cases, senior researchers also criticized organizational policies from the perspective of their academic field.

Selected quotes illustrate the content of each discourse. To maintain the anonymity of the interviewees, the quotes do not reveal specific academic fields, units, or positions of the interviewees.

Findings

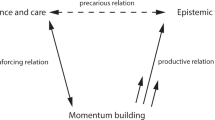

Based on the interview data, I discerned four distinct discourses. To some extent, the discourses compete with one another, while they are also parallel and intertwined. It was common for individual interviewees to draw on multiple discourses.

The first discourse is linked to a macrodiscourse of global competition for research excellence. The second discourse highlights the economic imperatives of income generation within a resource-poor context, framing resource scarcity as the overarching macrodiscourse. The third discourse views external grants as an instrument for organizational branding within the performative, marketing-oriented higher education and research system. Lastly, the fourth discourse underscores the role of research grants in identifying societally relevant research, aligning with the macrodiscourse of portraying universities and researchers as societally responsible actors.

Academic Discourse: Identifying Academic Stars via Competition

The first discourse regards external research grants as a pertinent and valuable assessment criterion, primarily due to its association with intense peer competition and low success rates. In this (idealized) discourse, utilizing grant funding as an assessment criterion is not viewed as unproblematic. Nevertheless, academically oriented funding success is seen as a relatively unambiguous, objective, and transparent indicator for measuring performance in recruitment processes. This is attributed to the legitimacy conferred through the peer review processes involved (cf. Townley et al. 2003).

Within this discourse, funding success is constructed as an indicator of an individual’s academic merit, particularly in terms of the quality of research on an international scale. In this discourse, quality is narrowly interpreted and connected to funding from sources constructed as especially prestigious. Thus, the outcomes of funding success on career advancement may differ depending on the source of funding. Funding recognized as prestigious in the interviews was associated with open competition and peer assessment processes, emphasizing the scholarly communities’ role in recognizing high-quality research (cf. Pietilä and Pinheiro 2021).

In the Finnish context, the funding sources considered prestigious included notably the Research Council of Finland and specific funding instruments allocated by the European Union, such as the European Research Council and the Horizon 2020 program. The essence of this discourse is effected by contrastive relational structures between academically oriented funding and funding designed for more applied or local purposes (cf. Fairclough 2003). An academic at career stage R4 with a project portfolio with diverse funding sources used the expression ‘good funding’ and ‘bad funding’ (with an ironic tone) to convey the attractiveness of different funding from the perspective of the university.

In a landscape where widespread publishing is commonplace, high-prestige academically oriented funding becomes a dividing line between academic ‘high-fliers’ and others (cf. Ylijoki and Ursin 2013). Thus, within the discourse, intense competition and peer review processes serve to identify academic stars, with grant success viewed as a surrogate for academic excellence. The following quote by an academic at career stage 4 highlights the role of competition in identifying the individuals with most potential for top performance.

Globally this [academic work and research] is enormously competitive. It [competition] is emphasized when applying for research funding. It is after all so that people who are able to receive funding, they are also able to achieve results. If we make changes to the [assessment] system, it does not change the fact that excellence is partly precisely created through competition. It is a difficult world when it’s [academic staff composition] a pyramid. Especially at the bottom of the pyramid you have to create possibilities to be able to show one’s capabilities. At the top [of the pyramid] you cannot avoid competition. After all, money is what drives many things. (R4 academic)

At the unit level, external grants were perceived as having positive implications, including the augmentation of the unit’s research capacity and intensity. An academic at career stage 4 characterized the success in securing grant funding as a demonstration of an academic’s ability to strengthen the research capacity within one’s faculty, thereby considering it a valid assessment criterion.

The academic discourse is situated within the broader science policy context, highlighting the global notion of research excellence as a driving force in academic recruitment (cf. Pietilä 2014). Success in securing research funding serves as an indicator of academics’ ability to build and manifest favorable attributes in this academic context. Such attributes include the capacity to identify one’s research niche within the international research landscape and to build international networks within one’s field.

This discourse was particularly employed by academics in leadership positions. Many of them asserted that in addition to research publications, external research grants constituted a key performance indicator in the evaluation of academic performance. This discourse holds significant discursive power as it draws on the legitimacy of scholarly communities via the involved peer review processes. This makes it difficult to present counterarguments. The discourse, often presented as self-evident, bestows authority upon research funding success as a quantitative, objectified measure. However, it fails to address questions, such as disparities in prerequisites for applying and obtaining grants (e.g., gendered division of labor in academia, including teaching load and academic housework, and unequal access to networks and institutional support), and one’s individual positioning with respect to targeted funding calls (cf. Brunila 2019, 367).

Economic Discourse: Being Able to Survive in the Harsh Funding Environment

The second discourse is situated within a national higher education and research context marked by limited financial resources and the imperative to demonstrate performance through tangible outputs. This discourse is dominated by the macrodiscourse on revenue generation, viewing external grants as a crucial requirement for survival in the competitive environment and for academics to conduct research in the first place. Academics in infrastructure-intensive fields and those requiring larger research consortia, in particular, frequently employed this discourse.

[The value of grants] goes back to the sums granted. When biomedical research is conducted, many things are expensive. If you receive, let’s say, a Horizon funding worth of one million from the EU, you can do things differently than with foundation funding or with project funding from the Academy of Finland. So in a way the recognition relates directly to the amounts granted. (R3 academic)

While the first discourse was associated with positive connotations of research excellence and academic judgement, the second discourse is characterized by more pragmatic terms. The economic necessity of generating research income was connected with realistic notions, such as the high costs of research and performance expectations placed on universities and units. Within the discourse, academics are assessed based on their potential to generate cashflows for the university. Several interviewees referred to the Matthew effect of cumulative advantage, where ‘money tends to come to money,’ illustrating that large international projects may be followed by extensions or local-level project spin-offs. However, the accumulation of funding in numerical terms was not always perceived to correspond with equivalent increases in the outcomes of work, raising concerns about the utility of research grants as an assessment criterion.

I would rather like to see more weight [in assessments] given to what has been produced, whether it is articles, databases, programs, or something like that rather than obtained funding. Because my view is that when funding starts to be accumulated within a certain group, money comes to money. But what is achieved with the funding, extra funding, the returns decrease. Rewarding someone based on the amount of money… it doesn’t necessarily tell how well it [funding] is used. Which means that its weight [in assessments] should be lowered. (R3 academic)

This discourse does not differentiate between funding sources but instead asserts that any form of funding is welcome and that ‘the more, the better.’ The macrodiscourse aligns with trends that view research through the lens of its financial potential, making research income a relevant and tangible assessment criterion in the context of limited funding. Within this discourse, the national performance-oriented funding model sets the conditions for organizational leeway, leaving academic leaders limited space in determining criteria for academic recruitment and promotion. In the national funding model, success in obtaining external grants also translates to increased resources for the university from the state.

The economic discourse was widely employed by the interviewees. Individuals’ discursive reactions ranged from adaptation to resentment. Those in leadership positions underscored the need to align with broader science policy, emphasizing coherence in how individual academics are evaluated and the incentives set by national science policy instruments.

In contrast, academics at career stages R2 and R3 often expressed more skepticism, advocating for more holistic assessment approaches that consider various aspects of performance in research, teaching, supervision, and societal outreach. Activities or achievements that are not easily quantifiable or displayed in economic terms were consistently perceived to be left in a shadow when individuals were rewarded through career decisions. Unrecognized aspects and activities of academic work included the quality of teaching and supervision, contributions to the scholarly community (e.g., editorial tasks), and societal outreach activities. Overall, the emphasis on grants was seen to shift the focus from academic contributions and the content of research to more crude measures, such as euros obtained (cf. Polster 2007, 610). Some post-doctoral researchers interpreted the focus on external grants as demoralizing, expressing a reluctance to be viewed merely as money-making machines.

The discourse underscores material aspects within the higher education and research system, including those related to employment. The questions of employment were raised by academics at career stages R2 and R3, approaching the issue from the perspective of academics rather than the university organization. From the perspective of securing one’s own or a junior colleague’s livelihood or conditions for continuing research, the scarcity of core-funded academic positions made all sort of funding attractive. For example, an academic at career stage R3 applied for funding to create employment opportunities for junior staff, even when facing no organizational mandate or incentives for participating in grant competitions.

My superior actually told me that I don’t have to apply for funding. It is no indicator or criterion [in my position], and other lecturers don’t apply for grants, either. My reason to continue applying is that I have colleagues and early-career researchers who don’t now receive any salary. (R3 academic)

Public Image Discourse: Contributing to Organizational Branding

The third discourse underscores the significance of external research grants in building organizational reputation and image in the consumer market. In this discourse, especially substantial funding from prestigious sources is an important symbol of success, benefiting not only the individual researcher, but also enhancing the university’s image as a modern research university. This discourse places emphasis on the university’s marketing initiatives and the importance of maintaining an active online presence to attract prospective academics, collaborators, students, and funding.

In this discourse, funding success contributes to the branding of the university, helping to portray the university as a modern organization equipped with competencies, such as competent leadership and support structures (cf. Krücken and Meier 2006). Thus, there may be incentives for the university organization to use achievements in external grant competitions as an assessment criterion because of the visibility and prestige attached to positive funding decisions.

This discourse was predominantly utilized by academics at the R2 and R3 levels, often with a tone of cynicism. During interviews, several academics pointed out that grant decisions tended to receive substantial visibility in the formal communication of the university. Similar to the economic discourse, interviewees expressed discontent with the public image discourse for prioritizing easily communicable achievements rather than communicating about the content of research. Academics criticizing the emphasis in communication wished to see more organizational appreciation and discussions about the topics that receive funding. Thus, the public image discourse was perceived as lacking substance.

At the moment, I think research funding is emphasized [in assessments]. I don’t know whether it means a shift to a private university or what kind of zeitgeist it tells about. But research grants seem to be emphasized. Both as an assessment criterion and for example in the way the university sends out press releases and stuff. Often they announce that somebody has gained funding, and not necessarily that something has been done. I think it’s a bit topsy-turvy approach. (R3 academic)

Yes, [externally-funded] projects are the ones people are being celebrated for. If somebody publishes a book with an international publisher, which is of course a huge sign of capability, especially if it is a prestigious […] publisher, it is somehow left in a shadow. (R3 academic)

The public image discourse places emphasis on the individual achievements of academics, particularly those in principal investigator roles. Some academics at career stage R2 stated that the focus on the official leaders of projects diminished the collaborative efforts involved in building research programs. A post-doctoral researcher who unofficially led a team in an externally funded project expressed the view that only individuals with formal leadership positions received recognition. She noted that the collective work involved in formulating research ideas and conducting the actual work often went unnoticed. Thus, there was a call for assessments to consider teamwork and tasks of each individual, including both de facto leadership responsibilities and the amount of academic housework.

Societal Discourse: Sorting Out ‘Relevant Research’

The fourth, societal discourse situates academic research and academics within the research policy landscape, which increasingly emphasizes the interconnections between academia and the wider society. In this discourse, promoted by significant actors, such as the European Union and the OECD, universities and individual academics as societally responsible actors are expected to contribute to solving the societal challenges of our time (e.g., Rask et al. 2017). To fulfil these expectations, specific funding instruments have been designed to support research endeavors in areas which are seen as societally relevant.

This discourse puts an emphasis on the third mission of universities. It can be contrasted with the academic discourse with no explicit emphasis on the esteemed societal relevance of research. The discourse was utilized especially by academics at the R3 and R4 levels.

It is noteworthy that many interviewees perceived that research proposals assessed as being ‘timely’ and relevant would be more likely to receive funding compared to proposals focused on fundamental research with no direct applications. This tendency was seen to be magnified by the university’s strategic emphasis on interdisciplinary approaches to address global challenges.

The academics did not fully embrace the societal orientation. Some criticized the current funding landscape in Finland for prioritizing interdisciplinary, problem-based research, interpreted to fit the modern societal image of research and universities. This emphasis was perceived to come at the cost of mono-disciplinary excellence and established traditions. The space for curiosity-driven basic research was perceived to be steadily shrinking due to cuts in public expenditure for higher education and research, coupled with the introduction of new policy-driven funding instruments.

I think we have gone wrong in this for long and we still do. Soon we will be in a situation where fundamental research in basic sciences is not funded at all. We basically only have at the EU level ERC [European Research Council] funding and in the Academy of Finland [Research Council of Finland] some funding instruments, which fund research in narrow fields, which is anyway all the time needed. Funding for basic research in the basic sciences is shrinking all the time. I'm really worried about that. (R4 academic)

The discourse makes visible the unequal opportunities for academics in different fields or with diverse research interests and epistemic orientations to obtain funding. This makes it problematic to use external grants as a recruitment criterion or as a performance indicator. A case in point is the funding granted by societally oriented funding streams, such as Horizon 2020 or the Strategic Research Council.

What I would perhaps like to add […] is exactly this external funding, let’s say applications for Horizon [2020] or Strategic Research Council. There are academic fields, which receive funding easier than others. […] If it is used as a criterion, then some fields and also some sub-fields within [my own field] would never be good in that sense. We must acknowledge that. There are some hot topics, some related to questions in climate and some related to environmental questions, it is easy for us [our unit] to take part in the funding competitions in those areas, but not necessarily in others. (R4 academic)

Therefore, funding success is tied to contemporary ideas and interest-laden struggles over which themes are considered societally relevant enough to merit funding. The discourse underscores that many funding instruments are, to some extent, politically steered, challenging the notion of free competition as portrayed in the academic discourse.

The acquisition of funding is, in my opinion… It is affected by so many things that I think it is quite problematic, if it is overly emphasized [in assessments]. People’s [research] topics are also so different, some topics are particularly pertinent to society at a given moment. If I think about my own research topic, when I received [funding] from the Academy [of Finland] last year, I recognized right away that the research was societally relevant at that specific time. Maybe in two years it wouldn’t have longer been. And somehow acknowledging this also in recruitment and researcher assessment, that there are many aspects of grant success that are not in your control. (R3 academic)

Summary of Findings

Table 2 provides a summary of the findings, delineating the four identified discourses and their connections to broader macrodiscourses within the higher education and research policy landscape. The table further specifies the societal context in which these discourses are embedded, outlining their main ambitions and characteristics.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper has examined how academics construct discourses on the significance of external research grants as an assessment criterion related to academic recruitment and career advancement. The analysis utilized data conducted via interviews with academics working at a Finnish university. The interviewees represented different academic fields and career stages.

In the conducted interviews, academics invoked a plurality of discourses. The variety of the identified discourses surrounding research grants underscores the varied expectations academics and university organizations are faced with, as has been underlined in previous research (cf. Kraatz and Block 2008; Pietilä and Pinheiro 2021). The discourses are also a manifestation of the tensions academics and university organizations face when trying to meet multiple expectations, reflected in career assessments. External research funding as a case in point simultaneously acts as a symbol for many things which explains why it a powerful indicator of success in the current higher education and research policy landscape.

Most importantly, funding success symbolizes the academic quality of an individual academic, signaling their ability to perform in a resource-poor environment. For universities, funding decisions are also helpful in identifying research that is seen to be particularly relevant in societal terms. Furthermore, funding decisions play a strategic role in communication, contributing to organizational prestige and visibility in the competitive attention economy. The discourses are aligned with narratives utilized not only in Finnish higher education and research policy, but also by powerful actors on a global scale. For example, perspectives emphasizing the international competitiveness and societal impact of research are pervasive science policy goals within the EU and OECD (see Drori et al. 2003; Ramirez 2010). The discourses reinforce the notion that competition through grants is not only important but also inevitable in an excellence-oriented yet resource-scarce landscape.

It is noteworthy that academics at different career stages resorted to some extent to different discourses and used them differently. Academics at the highest level especially endorsed the first two discourses, highlighting research excellence and economic imperatives. This is perhaps not surprising as the discourses align with the political visions and realities in the Finnish research policy landscape. In this context, these two discourses were often portrayed as uncontested and irrevocable, reflecting the specific dynamics of a performance-oriented research funding system and authority arrangements. These senior academics, in particular, perceived research grants as a significant assessment criterion due to the competitiveness of prestigious grants; setting the operational environment at the international level. On the other hand, academics at career stages R2 and R3 often drew on the economic, public image, and societal discourses, often pointing to their inherent shortcomings. These differences underscore the different operational environments and realities experienced by academics at different career stages and positions as well as the distinct work communities in which they engage.

Research funding is a tangible, seemingly neutral indicator, making it appealing for organizational purposes. However, the findings of the study point to factors, which challenge the presumed neutrality of using research funding success as an assessment criterion. For example, the study emphasizes that academics are not equally positioned in a science policy environment, which underscores the need to address global challenges (see also Ylijoki et al. 2011; Polster 2007). Thus, this study contributes to our understanding of the extent of these disparities, and their implications for equitable career progression and social dynamics within academia. It is also important to recognize the emotional reactions among academics regarding the significance of research grants in evaluating academic performance, given the potential (detrimental) impact on work well-being and work cohesion (see also Olsson 2022).

The findings are of relevance when universities design and renew academic recruitment and performance management systems. Grant funding success is an important criterion in many universities’ research assessment practices (Rice et al. 2020; Pontika et al. 2022; Saenen et al. 2019). However, the serendipity, political steering involved, and low success rates make it a problematic criterion in assessments. It is noteworthy that, for many researchers, the emphasis on research funding decisions in university communication reflects undesirable values in academia by celebrating individual achievements and success only in research. In line with the ambitions of CoARA, many academics at R2 and R3 career stages wished for more focus on the content of work, holistic assessments, and valuing the wider activities and roles of academics, rather than placing an emphasis on single indicators. At the same time, the study emphasizes that it is difficult to think of assessment systems which are misaligned with the incentive structures and logics of prestige university organizations are positioned in.

How different discourses are manifested, how they interconnect and evolve with respect to each other in different institutional settings, influenced by distinct national funding environments, is interesting for further research. An example is the emergence of new funding instruments that establish a connection between academic quality and societal relevance. In such a context, the academic discourse might increasingly intertwine with the societal discourse.

The findings of the study should be considered in lieu of limitations. Firstly, while the investigation resulted in discourses which are likely to have relevance beyond Finland, it would be significant to conduct studies in other countries to account for potential national nuances. Secondly, expanding the participant pool to include more individuals on tenure track career paths might have provided a more comprehensive understanding of the significance of research funds, considering the explicit performance pressures faced by individuals in these career paths (cf. Pietilä 2019). Thirdly, the study is time-specific and lacks a comparative aspect over time. Examining the topic longitudinally could shed light on how the discourses are linked to specific higher education and research policies over time and how they evolve.

References

Association of Finnish Independent Education Employers (2023). Statistical publication, universities. https://www.sivista.fi/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Tilastojulkaisu_2022_yliopistot.pdf

Bloch, C., Graversen, E.K. and Pedersen, H.S. (2014) Competitive research grants and their impact on career performance. Minerva 52: 77–96

Bol, T., de Vaan, M. and van de Rijt, A. (2018) ’The Matthew effect in science funding. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 115(19): 4887–4890

Brunila, K. (2019) '’Kiihdyttävä yliopisto’', in T. Autio, L. Hakala and T. Kujala (eds.) Siirtymiä ja ajan merkkejä koulutuksessa. Opetussuunnitelmatutkimuksen näkökulmiaTampere: Tampere University Press, pp. 349–376.

CoARA (2022). Agreement on reforming research assessment. 20 July 2022. https://coara.eu/agreement/the-agreement-full-text/.

DORA (2013). The Declaration [online]. https://sfdora.org/read/. Accessed 2 Jan 2023.

Drori, G.S., Meyer, J.W., Ramirez, F.O. and Schofer, E. (2003) 'The discourses of science policy', in G.S. Drori, J.W. Meyer, F.O. Ramirez and E. Schofer (eds.) Science in the modern world polity: Institutionalization and globalizationStanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 100–113.

EURAXESS (2023). Research profiles descriptors [online]. https://euraxess.ec.europa.eu/europe/career-development/training-researchers/research-profiles-descriptors, Accessed 20 July 2023.

Fairclough, N. (1992) Discourse and text: Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse & Society 3(2): 193–217

Fairclough, N. (2001) Language and Power, 2nd edn, Harlow: Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2003) Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research, London: Routledge.

Habicht, I.M., Lutter, M. and Schröder, M. (2021) How human capital, universities of excellence, third party funding, mobility and gender explain productivity in German political science. Scientometrics 126: 9649–9675

Harley, B. and Hardy, C. (2004) Firing blanks? An analysis of discursive struggle in HRM. Journal of Management Studies 41(3): 377–400

Kallio, K.-M., Kallio, T.J., Tienari, J. and Hyvönen, T. (2016) Ethos at stake: performance management and academic work in universities. Human Relations 69(3): 685–709

Kraatz, M.S. and Block, E.S. (2008) 'Organizational implications of institutional pluralism', in R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin-Andersson and R. Suddaby (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Organizational InstitutionalismLondon: Sage, pp. 243–275.

Krücken, G. and Meier, U. (2006) 'Turning the university into an organizational actor', in G.S. Drori, J.W. Meyer and W. Hwang (eds.) Globalization and Organization: World Society and Organizational ChangeOxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 241–257.

Lee, S. and Bozeman, B. (2005) The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science 35(5): 673–702

Lucas, L. (2006) The Research Game in Academic Life, Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Moher, D., Bouter, L., Kleinert, S., Glasziou, P., Sham, M.H., Barbour, V., et al. (2020) The Hong Kong principles for assessing researchers: fostering research integrity. PLoS Biology 18: e3000737

Olsson, P. (2022) The mental life of a telephone pole and other trifles: affective practices in the context of research funding. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 52(1): 84–107

Pietilä, M. (2014) The many faces of research profiling: academic leaders’ conceptions of research steering. Higher Education 67: 303–316

Pietilä, M. (2019) Incentivising academics: experiences and expectations of the tenure track in Finland. Studies in Higher Education 44(6): 932–945

Pietilä, M. and Pinheiro, R. (2021) Reaching for different ends through tenure track—institutional logics in university career systems. Higher Education 81: 1197–1213

Polster, C. (2007) The nature and implications of the growing importance of research grants to Canadian universities and academics. Higher Education 53(5): 599–622

Pontika, N., Klebel, T., Correia, A., Metzler, H., Knoth, P. and Ross-Hellauer, T. (2022) Indicators of research quality, quantity, openness and responsibility in institutional review, promotion and tenure policies across seven countries. Quantitative Science Studies 3(4): 888–911

Ramirez, F.O. (2010) 'Accounting for excellence: Transforming universities into organizational actors', in L.M. Portnoi, V.D. Rust and S.S. Bagley (eds.) Higher education, policy, and the global competition phenomenonPalgrave Macmillan, pp. 43–58.

Rask, M., Mačiukaitė-Žvinienė, S., Tauginienė, L., Dikčius, V., Matschoss, K., Aarrevaara, T. and d’Andrea, L. (2017) Public Participation, Science and Society: Tools for Dynamic and Responsible Governance of Research and Innovation, London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Rice, D.B, Raffoul, H., Ioannidis, J.P.A, and Moher, D. (2020) ‘Academic criteria for promotion and tenure in biomedical sciences faculties: Cross sectional analysis of international sample of universities’ BMJ, June, m2081.

Ross-Hellauer et al. (2023) Value dissonance in research(er) assessment: individual and perceived institutional priorities in review promotion and tenure Abstract Science and Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scad073

Saenen, B., Morais, R., Gaillard, V., and Borrell-Damián, L. (2019) Research assessment in the transition to open science: 2019 EUA open science and access survey results, European Universities Association.

Siekkinen, T., Kujala, E.-M., Pekkola, E., & Välimaa, J. (2021). Apurahatutkijat. Selvitys suomalaisten yliopistojen käytänteistä liittyen apurahatutkijoihin [Grant researchers. Report of the practices of Finnish universities regarding grant researchers]. Jyväskylän yliopisto.

Slaughter, S. and Leslie, L. (1997) Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies and the Entrepreneurial UniversityAcademic Capitalism: Politics, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Townley, B., Cooper, D.J. and Oakes, L. (2003) Performance measures and the rationalization of organizations. Organization Studies 24(7): 1045–1071

Vipunen database (2022) Education Statistics Finland. Universities’ research funding by statistical year. Vipunen: Education Statistics in Finland. https://vipunen.fi/en-gb/

Ylijoki, O.-H. and Ursin, J. (2013) The construction of academic identity in the changes of Finnish higher education. Studies in Higher Education 38(8): 1135–1149

Ylijoki, O.-H., Lyytinen, A. and Marttila, L. (2011) Different research markets: a disciplinary perspective. Higher Education 62: 721–740

Zhi, Q. and Meng, T. (2016) Funding allocation, inequality, and scientific research output: an empirical study based on the life science sector of Natural Science Foundation of China. Scientometrics 106: 603–628

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the YUFERING project of the YUFE university alliance. The project was supported by Horizon 2020 (grant agreement 101016967). Part of the interviews were conducted with Dr Jouni Kekäle. I wish to thank Dr Kekäle, Dr Katri Rintamäki, and other colleagues in YUFERING for the active discussions on research assessment. I am also grateful to all the informants who participated in the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (including Kuopio University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pietilä, M. From an Input to an Output: The Discursive Uses of External Research Funding in Academic Career Assessment. High Educ Policy (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-023-00339-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-023-00339-8