Abstract

Increasingly many citizens residing abroad maintain connections to their country of origin and follow its national elections. Considering that this group constitutes a growing share of the national electorate, it is essential to better understand factors that motivate electoral participation. In this study, we explore the role of economic, social and cultural ties in a unified analysis of turnout among Finnish citizens residing abroad. We rely on individual-level register data that cover the entire Finnish expatriate electorate (n = 96,290) and match their personal background characteristics (e.g. property ownership, length of stay abroad, language) with official turnout from the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections on the bases of personal identification codes. In line with the theoretical expectations, the results provide strong empirical evidence that non-resident citizens who maintain connections to the country of origin are more likely to vote in homeland elections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globalisation and European integration have led to increased geographical mobility. As a consequence, a growing number of people live temporarily or permanently in a country other than their homeland, i.e. the country that they emigrated from and hold citizenship of. On many occasions, these non-resident citizens closely follow homeland politics (Himmelroos and von Schoultz 2023 in this special issue). One of the main themes in the dialogue between non-resident citizens and their homeland concerns their legal, economic and political status in the homeland (Østergaard-Nielsen 2003). In particular, taxes, social security issues, political influence and voting rights are often on the top of the agenda. In response to a globally dispersed electorate, many countries have granted their non-resident citizens the right to vote in national elections over the past decades. In recent years, political participation of non-resident voters has been further facilitated by introducing various forms of convenience voting, such as early, postal or proxy voting, and special emigrant representatives elected from overseas electoral districts (Himmelroos and Peltoniemi 2021; Hutcheson and Arrighi 2015; Schmid et al. 2019).

Although the size and influence of the non-resident electorate is rapidly expanding, their participation in homeland elections remains relatively unexplored. Which factors motivate non-resident citizens to vote? While the strain between principles of democratic inclusion and policies expanding the enfranchisement of non-resident citizens has been addressed extensively (e.g. Bauböck 2003, 2015; López-Guerra 2005; Owen 2011; Rubio-Marín, 2006), the discussion has so far remained mainly at the theoretical level. Previous empirical research has, in turn, focused on determinants of support for emigrant voting rights (e.g. Collyer 2013; Himmelroos and Peltoniemi 2021; Lafleur 2011; Stutzer and Slotwinski 2021; Turcu and Urbatsch 2020; Wellman 2021), policy issues related to electoral incentives (e.g. Nemčok and Peltoniemi 2021; Wass, Peltoniemi, Weide, and Nemčok, 2021; Østergaard-Nielsen and Ciornei 2019) and allowing emigrants to elect special emigrant representatives (e.g. Burgess and Tyburski 2020; Palop-García, 2018; Peltoniemi 2016b; Umpierrez de Reguero and Dandoy 2021).

In addition to their scarcity, existing studies have suffered from certain methodological limitations stemming from their reliance on cross-sectional or poorly representative panel survey data with self-reported information on voting. To fill this gap in the literature, we address two research questions: First, who are non-resident voters and non-voters in terms of their sociodemographic and socioeconomic background? Second, what type of incentives do they have to vote or not to vote in homeland elections? We are particularly interested in economic, social and cultural ties that pull non-resident voters to their homeland, such as ownership of real estate, recipience of social benefits, remaining family members, language skills and length of stay.

In contrast with previous studies, our analyses are based on a unique dataset (n = 96,290) assembled by Statistics Finland that matches official turnout data from the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections with individual-level variables on the basis of personal identification numbers. Besides sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics, the data include information on individuals’ emigration history and turnout in previous elections. The Finnish context is particularly fruitful for this type of inquiry as Finland has been a latecomer in improving voting opportunities for non-resident citizens. While Finns either living or temporarily staying abroad during the parliament elections have been entitled to vote in advance in embassies and other designated polling stations, postal voting was not possible until the 2019 elections. So far, it seems to have had a relatively modest impact on mobilising the notably low participation among non-resident voters: turnout increased 2.5 percentage points between the 2015 (10.1%) and the 2019 (12.6%) elections.

Non-resident voters’ incentives to participate in homeland elections: economic, social and cultural ties

Non-resident citizens have been a largely overlooked group in the rich body of electoral studies. Lafleur and Sánchez-Domínguez (2015) suggest that this deficit is mainly due to the tendency of national election studies to collect data only within domestic borders. This is a particularly problematic limitation vis-à-vis our understanding of incentives for turnout. For instance, Niemi (1976) has argued that many people regard voting as no costlier than many other kinds of intermittent activities that they undertake. While this may be true among the domestic electorate, the costs of voting for non-resident citizens are often exceptionally high, causing turnout to be low in turn. Voting in person constitutes a dual constraint of distance and time, and postal voting may also be burdensome (Bhatti 2012; Dyck and Gimpel 2005; Nemčok and Peltoniemi 2021; Peltoniemi 2016a). Still, a share of non-residents decides to make the effort to participate. This implies that there might be some motivational factors involved which are not necessarily that relevant among domestic voters.

With an expansion of voting rights, non-resident citizens face four options: to vote only in the elections held in their current country of residence (if allowed), only in homeland elections, in both, or nowhere (Finn 2020). This decision is based on the characteristics of both country of residence and homeland. In general, contexts that are less receptive to immigrants tend to encourage stronger identification with the politics of the homeland (Østergaard-Nielsen 2001). If immigrants are marginalised in their country of residence, they may continue to feel a stronger belonging to their homeland. Under such circumstances, it is not exceptional for immigrants to be almost exclusively involved in homeland politics and less concerned about political issues in their country of residence. Exclusive political systems, such as Germany’s traditional jus sanguinis (see e.g. Scott 1930), can strengthen this type of homeland-orientated political identity among immigrants (Tsuda 2012).

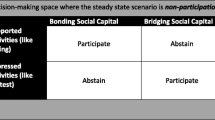

Individual-level conditions and social relations also play a central role in the formation and maintenance of political homeland-orientation. The terminology of bridging and bonding ties (Putnam 2000, 2002) suggests that there are economic, social and cultural networks that bring together people of different types (bridging), and networks which reinforce close-knit ties among people sharing similar backgrounds and predispositions (bonding) (see also Norris 2002). Bonding networks are limited within particular social niches. In this study, we differentiate between economic, social and cultural ties that link non-resident citizens to their homeland (Fig. 1). Each set of bonding ties increases the relevance of participating in homeland elections through different mechanisms.

Economic ties represent structural attachment to homeland institutions (cf. Gordon 1964), whereas social ties are based on interpersonal relationships and cultural ties are linked to national identity. In this study, we use ownership of real estate or recipience of social benefits (e.g. pension) as indicators of economic ties, family members as indicators of social ties and language skills, and the length of stay abroad as indicators of cultural ties. We expect that each of these will increase the propensity to vote in homeland elections.

Cross-border property ownership constitutes a concrete tie to the homeland that increases instrumental stakes in its elections, particularly as regards to issues including inflation and taxation. Maintaining and investing in financial assets after migration represent a durable form of cross-border engagement, and non-resident citizens do so for several reasons. They may maintain homeland financial assets (such as real estate and businesses) to support remaining family members, to preserve home country social status or to prepare for remigration (see e.g. Keister et al. 2020; Levitt and Schiller (2004); Palop-García and Pedroza 2019). The recipiency of social benefits, such as pensions, is another noteworthy economic factor that pulls voters to their homeland. Especially in the case of financial dependency, social benefits form a strong incentive to participate in homeland elections.

The central component in social ties is family, which has often been disregarded in studies conducted among emigrants (Föbker and Imani 2017). Family members in the homeland increase the motivation to follow, discuss and engage in homeland elections through the social logic of politics (Zuckerman 2005): it is no longer only an individual living abroad, but a wider social network that is affected by the domestic political decision-making (Umpierrez de Reguero and Jakobson 2023, in this special issue; Vintila, Pamies & Paradés, 2023, in this special issue). In addition, family members living in the homeland lower the costs and risks of emigration and increase its expected returns.

The third group of pull factors is linked to integration with the country of residence on the one hand and maintenance of previous national identity on the other. While these two are not mutually exclusive (see e.g. Tsuda 2012), conditions that hinder or even prevent full membership in the current country of residence may increase leanings towards the homeland. Especially, language skills play a pivotal role in influencing immigrants’ experience of intercultural interaction and cultural adaptation through language-based rejection sensitivity (i.e. the tendency to anxiously expect rejection from native speakers due to a lack of language proficiency) (Lou and Noels 2017). The national language is widely required for access to education, employment, housing and achievement of successful integration. Therefore, immigrants are perceived as having a deficit even if native speakers might also lack many language skills (Wodak 2013). Sharing the same native language (such as the case of migrants between, for example, Latin American countries and Spain; Canada and France; English-speaking countries; and Swedish-speaking Finns and Sweden) gives immigrants an edge in comparison with immigrants from other countries. In a similar fashion, inadequate language skills may also foster an orientation towards the homeland when it comes to political engagement (see e.g. Hartmann 2015; Turcu and Urbatsch 2014). We assume this trend to be notable the other way around as well: if non-resident citizens speak one of the national languages as a mother tongue, they would presumably have a stronger political homeland-bound engagement and thus a higher propensity to vote in its elections. That is because speech has a distinct cultural and political value. A certain level of proficiency is needed to understand symbolic expressions and metaphors characteristic of political speech. That is particularly the case in Finland where both national languages (Finnish and Swedish) are spoken by very few people globally.

There are certain demographic characteristics of the non-resident citizens, which determine the resources available for mobilisation. For instance, age, education, gender and income influence involvement (Quinsaat 2013). In addition, the length of residence makes a difference in terms of cultural ties: the longer migrants stay in their current country of residence, the stronger the trend towards integration will be. Peltoniemi (2016a) has previously suggested that time lived abroad influences voting both in the homeland and in the country of residence. Whereas voting in homeland elections starts to decline as time goes by, voting in the country of residence gradually increases.

The effect of pull factors may be strengthened or mitigated by an individual's personal characteristics. Age, in particular, is often essential for homeland-oriented political identity. Transnational political practices are mostly a concern of the first generation, as younger generations are usually less interested in homeland politics than their parents. Furthermore, the political loyalties of the first generation may be qualitatively different from those of the second and third generations, who have developed a homeland political standpoint from afar (Bauböck 2003, 2005; Föbker and Imani 2017; Lou and Noels 2017; Østergaard-Nielsen 2001).

The context: non-resident Finnish citizens as voters from abroad

Finland has a relatively long history with emigration. During the twentieth century, approximately one million Finns emigrated. There have been two distinct waves of emigration from Finland. From 1880 to 1930, 400,000 Finns emigrated to North America altogether, first mostly to the USA and after 1924 to Canada. The second wave of emigration took place during the 1960s and 1970s and was mostly directed to the neighbouring country of Sweden. Between 1969 and 1970, net migration from Finland to Sweden was 80,000 persons, and since the end of the Second World War, around 300,000 Finns have emigrated to Sweden permanently. Urbanisation as well as the entrance of large age cohorts born after WW2 to the labour market has been cited as the main reasons for the latter wave of migration. Since the 1980s, emigration from Finland has been more Europe-centred (Koivukangas 2003; Peltoniemi 2018).

Non-resident Finnish citizens have been able to vote from abroad since the 1970s, but their turnout has remained low, fluctuating around ten percent. Over the last two decades, Finnish governments have been searching for solutions to better engage the ever-increasing electorate abroad (Wass et al. 2021). Improving voting opportunities for Finns living abroad was highlighted in the government policy programmes for non-resident Finns for 2006–2011 and 2012–2016, in which the introduction of postal voting was presented as a possible way to increase turnout. However, in comparison, Finns living in EU member states had relatively good political rights as they were eligible to run for office and cast a ballot abroad in embassies and other designated facilities. In the 2019 parliamentary elections, postal voting from abroad was enabled for the first time. A substantive portion (14.1%) of non-resident voters took advantage of this novel voter facilitation instrument. Simultaneously, turnout among non-resident voters increased by 2.5 percentage points to 12.6 percent, which was a record although still significantly lower than turnout among Finns living in Finland (72.1%) (Parliamentary elections 1983–2019, data on voting, 2021). In addition to postal voting, in-person on-site voting continues to be possible.

In order to vote by mail, voters living abroad must order the required documents from the subscription service of the Ministry of Justice and deliver their ballot, at their own expense, to the Central Electoral Commission of the correct municipality no later than two days before the election. Furthermore, two adults must be present at the voting location as witnesses and must confirm their presence with their signatures and contact information, which must be submitted along with the sealed ballot. In essence, great responsibility rests on the individual voter instead of on the electoral authority in postal voting. Voters also have to rely on the efficiency of the post to deliver the ballots in time. This is echoed by recent findings suggesting that trust acts as a moderator between distance to the polling station and non-resident Finns’ probability of postal voting (Nemčok and Peltoniemi 2021; Wass et al. 2021; Weide 2021).

So far, Finnish parties have largely disregarded expatriate voters in spite of the considerable size of the non-resident electorate (nearly 6 percent of all eligible voters resided abroad during the 2019 parliamentary electionsFootnote 1). The activity of NGOs has compensated for this deficit to a certain extent. The two collective interest groups, namely the Finland Society and the Finnish Expatriate Parliament, have played a visible role in representing and lobbying for non-resident voters’ needs and political preferences. Besides introducing postal voting in the Election Act in 2017, their key successes include the changes in the Nationality Act allowing dual and multiple citizenship in 2003.

Research design

Data

To empirically assess the factors influencing electoral participation among voters residing abroad, we use individual-level register data that cover the entire Finnish electorate living abroad. Our dataset matches official voting records for non-resident citizens with individual-level data compiled by Statistics Finland.Footnote 2 The use of official voting records means that we avoid the problems of misreporting and over-reporting that bias self-reports of turnout (see e.g. Karp and Brockington 2005; Sciarini and Goldberg 2016; Selb and Munzert 2013). The dataset includes 268,400 individuals altogether. However, as is often the case with datasets drawn from population registers, some of the information necessary to study the set research question is missing. This means that the total number of observations available to this analysis is 96,290. To ensure comparability of the findings across all parts of the analysis, we estimate the models using the same 96,290 observations. Despite a dropout rate due to data availability, this dataset includes, to the best of our knowledge, the most accurate and comprehensive information on electoral participation among citizens residing abroad used in the field to date.

The dependent variable, voting in the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections, is coded as binary (0 = did not vote, 1 = voted). As outlined in the theoretical section, we examine four sets of pull factors which are expected to increase voting propensity in homeland elections among non-resident citizens. Economic ties to the country of origin are measured in two ways: home ownership in FinlandFootnote 3 (owning a home or a share of a home) and receipt of a pension.Footnote 4 Both variables are coded as binary (0 = does not own a home / does not receive pension, 1 = owns a home /receives a pension).

Social ties to the country of origin are operationalised as a set of dummy variables capturing the citizenship and country of residence of various family members. First, we examine the propensity to vote among non-resident citizens, one or both parents of whom are holders of Finnish citizenship (as compared to individuals with non-citizen parents). In addition, we examine turnout among those whose spouse holds a Finnish citizenship (as opposed to individuals with non-citizen spouses). We also look at the effect of siblings and children living abroad. Whereas we expect parents and a spouse to contribute to tighter social ties to the homeland and hence boost turnout, the effect should be the opposite in the case of siblings and children living abroad. The reason for this opposite and potentially confusing operationalisation stems from the practice of Statistics Finland to code such information.

Cultural ties to the country of origin are measured by language skills and the length of stay abroad. In the Finnish population register, an individual is classified as having only one spoken language, presumably their mother tongue.Footnote 5 We use this information to compare the separate voting propensities among those who speak one of the two main official languages in Finland (Finnish and Swedish) as compared to the native speakers of any other language (which constitutes a pooled residual category). The length of stay is calculated as the time between the year of emigration and 2019, the year in which parliamentary elections were held. As gender potentially influences a non-resident's voting propensity (e.g. Quinsaat 2013), it has been controlled for. However, we are not able to include education as a control variable. As a substantial proportion of non-resident citizens have received their education (at least partly) abroad, their educational information is not up to date in the Finnish population register.Footnote 6 Descriptive statistics for all variables is available in online appendix (Table A1).

Modelling strategy

Given the binary character of our dependent variable, we estimate a set of binomial logistic regression models. We begin with a model that includes only the variables indicating different types of ties to the homeland. We then add two control covariates (i.e. gender and age) to hold the potential effect of these two individual-level attributes constant. These two steps are repeated four times for (1) economic ties; (2) social ties; and cultural ties with separate estimation for (3) spoken language and (4) the length of stay. Although mother tongue and the length of stay are both used as indicators for cultural ties, they measure somewhat different mechanisms, which is why we keep them distinct in our empirical analysis.Footnote 7

As the last step, we estimate two full models—one including all pull factors, and a second adding two control covariates. The full model, including economic, social and cultural ties to homeland and control covariates, is used as a basis for the empirical testing of our expectations. However, the results are largely consistent across various model specifications and adding more covariates has implications only on the size of the effects, which decreases to some degree.

Results

Before evaluating the empirical support for our expectations concerning the boosting effect of economic, social and cultural ties on turnout among non-resident citizens, it is important to acknowledge a specific aspect of the analysis. The fact that we use an extensive database covering 96,290 individuals implies that conventionally applied thresholds of statistical significance provide only limited guidance for assessing the relevance of our findings. With such a high number of observations, it is easy to pass the conventionally used p-values. When interpreting the empirical results, we therefore pay only limited attention to statistical significance and primarily evaluate the coefficients with respect to their effect size and the related substantive relevance.

We first evaluate the role of economic ties to homeland, drawing from the assumption that home ownership and pension recipiency increase propensity to vote in homeland elections. Models 1 and 2 in Table 1 show that both have a noteworthy positive effect. Even though the size of the coefficients decreases when the remaining variables are added to the model (see Models 9 and 10), the coefficients remain positive. This suggests that even when we hold indicators of social and cultural ties constant, economic ties maintain their explanatory power. When the log-odds from Model 10 in Table 1 are transformed into more intuitive probabilities,Footnote 8 the likelihood that a person without any of the included characteristics voted in the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections is around five percent. This serves as a baseline against which we will evaluate the other coefficients.

Interestingly, pension recipiency has the strongest positive association with voting in homeland elections (see Fig. 2 for visualised effects). Those who received pensions from Finland were roughly 70 percentage points more likely to vote in the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections than those who did not. Despite its somewhat smaller effect, home ownership (i.e. owning a home or a share of a home) considerably increases voting propensity by some 50 percentage points (compared to people who do not own property in Finland). Based on these findings, it is safe to conclude that economic ties indeed increase electoral participation among Finnish citizens residing abroad.

Visualisation of the main findings. The marginal effects are divided into four panels in line with the tested hypotheses. Visualisations are based on odds ratios from Model 10 in Table 1. Positive odds ratio indicates that the person with a given characteristic is more likely to vote compared to a person without any of the factors included in Model 10 (the “constant” from the model). In the case of the “length of stay abroad” (lower left panel), visualisation is based on predicted probabilities of voting depending on how long ago the person emigrated from Finland

As described in the previous section, we use several variables to measure the association between social ties and voting in homeland elections. Beginning with parents, Model 10 shows that having one parent who is a Finnish citizen increases an individual's voting probability by slightly over 50 percentage points compared to individuals with parents holding foreign citizenships. In the case of both parents being Finnish citizens, the probability increases by an additional eight percentage points. Hence, parents comprise an important component in social ties. We also find a positive association in the case of a spouse holding a Finnish citizenship: the probability of a non-resident citizen whose spouse is also a citizen to vote in the 2019 elections was 52 percentage points higher compared to individuals with non-citizen spouses. These trends are unambiguous, suggesting that Finnish citizenship of family members is strongly associated with substantially increased probability of non-resident citizens to engage in homeland elections.

We also assume that family members living abroad will contribute to weaker homeland-bound social ties. Contrary to our expectation, these covariates yield positive coefficients: having siblings who also reside abroad is associated with increased turnout rates. The probability of voting is approximately 50 percentage points higher compared to those with no siblings living outside Finland, and the association is of similar size regardless of the number of siblings. This increased predicted probability is only slightly lower compared to non-resident citizens with a Finnish parent or spouse. The estimates are slightly lower, but still positive, for those who have at least one child residing abroad: their turnout probability amounts to 52 percent, which is roughly 47 percentage points higher than the constant (i.e. the estimate for an individual without any of the characteristics included in the model). Hence, siblings and children living abroad, which we expected to weaken social ties to the homeland, seem to be associated with increased turnout rates. This may be due to the siblings or children accompanying the voters when emigrating from Finland. These individuals may be surrounded by their Finnish family members, and hence, such a “family bubble” may lower the impact of foreign residency on one’s propensity to vote. However, our data are unable to provide any further insights into this proposition.

The final set of factors tackles the cultural ties to homeland. The literature review presented in the theoretical section gave us strong reasons to focus separately on the spoken language of the homeland (strengthening cultural ties to homeland) and the length of stay abroad (assumed to weaken connection to the homeland). With respect to the former, both Finnish and Swedish speakers (i.e. citizens speaking one of the two main official languages of Finland as their mother tongue) were indeed more likely to vote in the 2019 parliamentary elections. While citizens residing abroad who do not speak either of these two languages have only a roughly five percent probability to vote (as the constant implies), it is around 53 percentage points higher for Finnish speakers and 55 percentage points higher for Swedish speakers.Footnote 9 These findings suggest that the cultural connection based on the homeland language is likely to increase motivation to participate in homeland elections.

As the final step, we interpret the strength of cultural ties to the homeland, which presumably decline with increasing time spent abroad. This is the only continuous variable in the models, and therefore, a visualisation of its marginal effect in the lower left panel of Fig. 2 provides a more intuitive interpretation than the log-odds reported in Table 1. As can be seen, the probability of Finnish non-resident citizens to participate in the national parliamentary elections is slightly below ten percent shortly after their emigration, everything else held constant. As time goes by, the estimated probability to turnout continuously decreases to around 2.5 percent for the longest non-resident citizens included in the dataset, who emigrated 40 years ago. This means that the probability decreases by roughly three-quarters (i.e. 7.5 percentage points) which constitutes a substantive drop in the propensity to turn out. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that a declining strength of cultural ties to the homeland, approximated by the increasing period spent abroad, plays a substantive role in the decision to participate in national elections held in the homeland.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to explore how economic, social and cultural ties to the homeland are linked with non-resident voters’ propensity to participate in homeland elections. Using data (n = 96,290) that match official turnout in the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections with individual-level voter characteristics, we found that home ownership and recipiency of pension, serving as indicators for economic ties, increased the motivation to vote. The same applied to (lack of) language skills and length of stay, which served as indicators for cultural ties. However, our findings provided mixed evidence on social ties’ influence on turnout. Having family members who hold Finnish citizenship was strongly associated with increased probability of voting, as expected, but so did having family members living abroad. It thus appears that having interpersonal relations overall increases the relevance of political participation (see e.g. Rolfe 2012; Zuckerman 2005). It is possible that such family ties form an additional social bond, especially if everyone is active in homeland elections. However, this remains an issue for future studies as the register data available here did not enable us to explore this possibility further.

Altogether, it is not particularly surprising that non-resident citizens find voting more rewarding when they have higher stakes in the form of various ties that emphasise the link between an individual’s living conditions and political decision-making. While the outputs of political decision-making may not have the same implications for non-resident citizens as they do for residents, non-residents are still subject to certain laws and policies, especially those concerning constitutional matters and citizenship (Honohan 2011; Owen 2011). Furthermore, if non-resident citizens own property or have close relatives in their country of origin, they are likely to be affected by legislation on taxation or social security to some degree (Himmelroos and Peltoniemi 2021). Our findings suggest that non-residents spontaneously apply such all-affected principles (Dahl 1970, see also Näsström, 2011) by being mobilised by concrete ties that connect them to homeland politics.

Change history

23 March 2023

In this article the third author's affiliation has been updated.

Notes

In the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections, a total of 254,574 eligible voters resided abroad. In comparison, of the 12 mainland electoral districts, three had smaller electorates than the number of eligible voters abroad.

The dataset is under license, granted to the authors by Statistics Finland. The authors are thus not allowed to make the dataset publicly available. To access the data, please contact info@stat.fi.

Finland implements a real estate practice in which the apartment owners are formally in possession of a share of their building.

Persons who live in the EU or an EEA country, Switzerland or a country that has a social security agreement with Finland can apply for a national pension or an earnings-related pension. Persons who live in another country but have previously worked in Finland can apply for earnings-related pensions (Kela, 2021).

The Finnish register attributes only one spoken language to each person. This policy causes some uncertainty in the case of citizens with multiple and thus bilingual identity (especially among members of the Swedish-speaking minority). For the purpose of this study, we try to circumvent such potential inaccuracy by focusing on the language closest to a person’s cultural and personal background.

The dataset includes information on parental education. However, it would have been highly unreliable as a proxy for an individual’s education although these two overlap to some extent.

We also estimate a separate model per each independent variable in order to assess whether imputation in groups has any impact on the findings. The results are presented in Table A2 (models including solely individual variables) and Table A3 (models adding controls – gender and age). The estimates are largely consistent, suggesting that grouping the variables following our theoretical reasoning has no impact on the findings.

The probabilities can be calculated by entering the coefficient into the formula \(e^{x}/(1+e^{x})\).

The tendency of the Swedish-speaking minority to participate in elections at higher rates compared to Finnish speakers has been observed repeatedly in national election studies, reflecting their often more advantaged socio-economic position and close social and political networks (see Medeiros, von Schoultz, and Wass 2019). Therefore, both resident and non-resident electorates reveal similar trends, which is reassuring with respect to the reliability of the register database used in this study.

References

Bauböck, R. 2003. Towards a political theory of migrant transnationalism. International Migration Review 37 (3): 700–723.

Bauböck, R. 2005. Expansive citizenship: Voting beyond territory and membership. PS: Political Science 38: 683–687. https://doi.org/10.1017/S10490965050341.

Bauböck, R. 2015. Morphing the Demos into the right shape. Normative principles for enfranchising resident aliens and expatriate citizens. Democratization 22 (5): 820–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.988146.

Beckman, L. 2014. Democracy and the Right to Exclusion. Res Publica 20 (4): 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-014-9253-y.

Bhatti, Y. 2012. Distance and Voting: Evidence from Danish Municipalities. Scandinavian Political Studies 35 (2): 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00283.x.

Burgess, K., and M.D. Tyburski. 2020. When Parties go Abroad: Explaining Patterns of Extraterritorial Voting. Electoral Studies 66: 102–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102169.

Collyer, M. 2013. A Geography of Extra-Territorial Citizenship: Explanations of External Voting. Migration Studies 2 (1): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mns008.

Dahl, R. 1970. After the Revolution? Authority in a Good Society. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dyck, J.J., and J.G. Gimpel. 2005. Distance, Turnout, and the Convenience of Voting. Social Science Quarterly 86 (3): 531–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2005.00316.x.

Erman, E. 2013. Political Equality and Legitimacy in a Global Context. In Political Equality in Transnational Democracy, ed. E. Erman and S. Näsström, 61–87. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Finn, V. 2020. Migrant voting: Here, there, in both Countries, or Nowhere. Citizenship Studies 24 (6): 730–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2020.1745154.

Föbker, S., and D. Imani. 2017. The Role of Language Skills in the Settling-in Process—Experiences of Highly Skilled Migrants’ Accompanying Partners in Germany and the UK. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2720–2737. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314596.

Gordon, M. 1964. Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hartmann, C. 2015. Expatriates as Voters? The New Dynamics of External Voting in Sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization 22 (5): 906–926. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.979800.

Himmelroos S., and von Schoultz, Å. 2023. The Mobilizing Effects of Political Media Consumption Among External Voters. European Political Science, 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-022-00406-5.

Himmelroos, S., and J. Peltoniemi. 2021. External Voting Rights from a Citizen Perspective—Comparing Resident and Non-resident Citizens. Attitudes towards External Voting’, Scandinavian Political Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12211.

Honohan, I. 2011. Should Irish Emigrants have Votes? External Voting in Ireland. Irish Political Studies 26 (4): 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2011.619749.

Hutcheson, D.S., and J.-T. Arrighi. 2015. Keeping Pandora’s (ballot) Box Half-Shut: A Comparative Inquiry into the Institutional Limits of External Voting in EU Member States. Democratization 22 (5): 884–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.979161.

Karp, J.A., and D. Brockington. 2005. Social Desirability and Response Validity: A Comparative Analysis of Overreporting Voter Turnout in Five Countries. The Journal of Politics 67 (3): 825–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00341.x.

Keister, L.A., J. Agius Vallejo, and P.B. Smith. 2020. Investing in the Homeland: Cross-Border Investments and Immigrant Wealth in the U.S. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (18): 3785–3807. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1592875.

Kela. 2021. Pension from Finland to Another Country. Retrieved from https://www.kela.fi/web/en/pension-from-finland-to-another-country

Koivukangas, O. 2003. Finns Abroad. A short history of Finnish emigration. Retrieved from http://www.migrationinstitute.fi/files/pdf/artikkelit/finns_abroad_-_a_short_history_of_finnish_emigration.pdf

Lafleur, J.-M. 2011. ‘Why do States Enfranchise Citizens Abroad? Comparative Insights from Mexico, Italy and Belgium’, Global Networks 11: 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00332.x.

Lafleur, J.-M., and M. Sánchez-Domínguez. 2015. The Political Choices of Emigrants Voting in Home Country Elections: A Socio-Political Analysis of the Electoral Behaviour of Bolivian External Voters. Migration Studies 3 (2): 155–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnu030.

Levitt, P., and N. Glick Schiller. 2004. Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society. International Migration Review 38 (3): 1002–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00227.x.

López-Guerra, C. 2005. Should Expatriates Vote? The Journal of Political Philosophy 13: 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2005.00221.x.

Lou, N.M., and K.A. Noels. 2017. Sensitivity to Language-based Rejection in Intercultural Communication: The Role of Language Mindsets and Implications for Migrants’ Cross-cultural Adaptation’. Applied Linguistics 40 (3): 478–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx047.

Medeiros, M., Å. von Schoultz, and Hanna Wass. 2019. Language Matters? Antecedents and Political Consequences of Support for Bilingualism in Canada and Finland. Comparative European Politics 18: 532–559. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00198-x.

Näsström, S. 2011. The Challenge of the All-Affected Principle. Political Studies 59 (1): 116–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00845.x.

Näsström, S. 2015. Democratic Representation Beyond Election. Constellations 22 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.12123.

Nemčok, M., and J. Peltoniemi. 2021. Distance and Trust: An Examination of the Two Opposing Factors Impacting Adoption of Postal Voting Among Citizens Living Abroad. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09709-7.

Niemi, R. 1976. Costs of Voting and Nonvoting. Public Choice 27 (1): 115–119.

Norris, P. 2002. The Bridging and Bonding Role of Online Communities. Harvard International Journal of Press/politics 7 (3): 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X0200700301.

Østergaard-Nielsen, E. 2001. Transnational political practices and the receiving state: Turks and Kurds in Germany and the Netherlands. Global Networks 1 (3): 261–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00016.

Østergaard-Nielsen, E. 2003. Transnational Politics: The Case of Turks and Kurds in Germany. London: Taylor and Francis e-library.

Østergaard-Nielsen, E., and I. Ciornei. 2019. Making the Absent Present: Political Parties and Emigrant Issues in Country of Origin Parliaments. Party Politics 25 (2): 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817697629.

Owen, D. 2011. Transnational Citizenship and the Democratic State: Modes of Membership and Voting Rights. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 14 (5): 641–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2011.617123.

Palop-García, P. 2018. Contained or Represented? The Varied Consequences of Reserved Seats for Emigrants in the Legislatures of Ecuador and Colombia. Comparative Migration Studies 6 (1): 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0101-7.

Palop-García, P., and L. Pedroza. 2019. Passed, regulated, or applied? The different stages of emigrant enfranchisement in Latin America and the Caribbean. Democratization 26 (3): 401–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2018.1534827.

Parliamentary elections 1983–2019, data on voting. 2021. Retrieved from: https://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__vaa__evaa__evaa_as/010_evaa_2019_tau_110.px/

Peltoniemi, J. 2016a. Distance as a Cost of Cross-Border Voting. Research on Finnish Society 9: 19–32.

Peltoniemi, J. 2016b. Overseas Voters and Representational Deficit: Regional Representation Challenged by Emigration. Representation 52 (4): 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2017.1300602.

Peltoniemi, J. 2018. On the Borderlines of Voting: Finnish Emigrants’ Transnational Identities and Political Participation (Doctoral Dissertation ed.). Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling Alone. New York: Free Press.

Putnam, R.D. 2002. Introduction. In In the Dynamics of Social Capital, ed. R.D. Putnam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quinsaat, S.M. 2013. Migrant Mobilization for Homeland Politics: A Social Movement Approach. Sociology Compass 7 (11): 952–964. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12086.

Rolfe, M. 2012. Voter Turnout: A Social Theory of Political Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rubio-Marín, R. 2006. Transnational Politics and Democratic Nation-State: Normative Challenges of Expatriate Voting and Nationality Retention of Emigrants. New York University Law Review 81 (1): 117–147.

Schmid, S.D., L. Piccoli, and J.-T. Arrighi. 2019. Non-Universal Suffrage: Measuring Electoral Inclusion in Contemporary Democracies. European Political Science 18 (4): 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-019-00202-8.

Sciarini, P., and A.C. Goldberg. 2016. Turnout Bias in Postelection Surveys: Political Involvement, Survey Participation, and Vote Overreporting. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 4 (1): 110–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/jssam/smv039.

Scott, J.B. 1930. Nationality: Jus Soli or Jus Sanguinis. The American Journal of International Law 24 (1): 58–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2189299.

Selb, P., and S. Munzert. 2013. Voter Overrepresentation, Vote Misreporting, and Turnout Bias in Postelection Surveys. Electoral Studies 32 (1): 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.11.004.

Stutzer, A., and M. Slotwinski. 2021. Power Sharing at the Local level: Evidence on Opting-in for Non-Citizen Voting Rights. Constitutional Political Economy 32 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-020-09322-6.

Tsuda, T. 2012. Whatever Happened to Simultaneity? Transnational Migration Theory and Dual Engagement in Sending and Receiving Countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (4): 631–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.659126.

Turcu, A., and R. Urbatsch. 2014. Diffusion of Diaspora Enfranchisement Norms: A Multinational Study. Comparative Political Studies 48 (4): 407–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414014546331.

Turcu, A., and R. Urbatsch. 2020. European Ruling Parties Electoral Strategies and Overseas Enfranchisement Policies. European Journal of Political Research 59 (2): 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12357.

Umpierrez de Reguero, S., and Jakobson, M. 2023. Explaining Support for Populists among External Voters. European Political Science, 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-022-00403-8.

Umpierrez de Reguero, S., and R. Dandoy. 2021. ‘Should we go Abroad? The Strategic Entry of Ecuadorian Political Parties in Overseas Electoral Districts. Representation. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2021.1902850.

Vintila, D., Pamies C., and Paradés, M. 2023. Electoral (Non)Alignment between Resident and Non-Resident Voters: Evidence from Spain. European Political Science, 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-022-00411-8.

Wass, H., J. Peltoniemi, M. Weide, and M. Nemčok. 2021. Signed, Sealed, and Delivered with Trust: Non-Resident Citizens Experiences of Newly Adopted Postal Voting. Frontiers in Political Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.692396.

Weide, M. 2021. Practicing Ballot Secrecy: Postal Voting and the Witness Requirement at the 2019 Finnish Elections. Frontiers in Political Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.630001.

Wellman, E.I. 2021. Emigrant Inclusion in Home Country Elections: Theory and Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. American Political Science Review 115 (1): 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000866.

Wodak, R. 2013. Dis-Citizenship and Migration: A Critical Discourse-Analytical Perspective. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 12 (3): 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2013.797258.

Zuckerman, A.S. 2005. The Social Logic of Politics: Personal Networks as Contexts for Political Behavior. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peltoniemi, J., Nemčok, M. & Wass, H. With pulling ties, electoral participation flies: factors mobilising turnout among non-resident Finnish voters. Eur Polit Sci 22, 83–100 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-022-00404-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-022-00404-7