Abstract

Studies estimating the consequences of immigration on wages paid to native-born workers often reveal small-to-nonexistent effects when using cross city or state variation (the “spatial approach”) but large deleterious effects when using variation across education-by-experience cells (the “national approach”). One mechanism of labor market adjustment emphasized in the spatial approach is that native-born workers respond to immigration by specializing in occupations demanding skills in which they have a comparative advantage, thereby helping to protect themselves from labor market competition and wage losses. This paper examines whether the national approach also identifies this skill response. We find evidence that such a response does occur among workers without college experience. However, regressions using traditional education-by-experience cells do not find skill reallocation consistent with comparative advantage for college-educated natives. This result points to limitations of the education-by-experience cell model.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Sara de la Rica (2011). “Complements or substitutes? Task specialization by gender and nativity in Spain,” Labour Economics, Elsevier, vol. 18(5): 697–707

Aydemir, Abdurrahman and George J. Borjas (2007). “Cross-Country Variation in the Impact of International Migration: Canada, Mexico, and the United States,” Journal of the European Economic Association, vol. 5(4): 663–708

Borjas, George J., and Lawrence F. Katz. 2007. “The Evolution of the Mexican-Born Workforce in the United States.” In Mexican Immigration to the United States, ed. George J. Borjas, 13–56. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Borjas, George J. (2003) “The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4): 1335–1374

Borjas, George J. (2013). “Immigration and the American Worker: A Review of the Academic Literature.” Center for Immigration Studies, April 2013

Borjas, George J. (2014). Immigration Economics. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA

Borjas, George J., Jeffrey Grogger, and Gordon H. Hanson (2010). “Immigration and the Economic Status of African-American Men,” Economica, London School of Economics and Political Science, vol. 77(306): 255–282

Borjas, George J., Jeffrey Grogger, and Gordon H. Hanson (2011). “Substitution between Immigrants, Natives, and Skill Groups,” NBER Working Papers 17461

Borjas, George J., Jeffrey Grogger, and Gordon H. Hanson (2012). “Comment: On Estimating Elasticities of Substitution.” Journal of the European Economic Association. Vol. 10(1): 198–210

Card, David (1990). “The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 43(2): 245–57

Card, David (2001). “Immigrant Inflows, Native Outflows, and the Local Labor Market Impacts of Higher Immigration.” Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1): 22–64

Card, David (2009a). “How Immigration Affects US Cities” in Robert Inman, editor, Urban Enigma: City Problems, City Prospects. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009

Card, David (2009b). “Immigration and Inequality.” American Economic Review, 99(2), 1–21

Card, David (2012). “Comment: The Elusive Search for Negative Wage Impacts of Immigration.” Journal of the European Economic Association. Vol. 10(1): 211–215

De Arcangelis, Giuseppe, Edoaardo Di Porto, and Gianluca Santoni (2015), “Migration, Labor Tasks, and Production Structure” CSEF Working Paper No. 390, Centre for Studies in Economics and Finance

Grossman, Jean Baldwin (1982). “The Substitutability of Natives and Immigrants in Production.” The Review of Economics and Statistics. Vol. 64(4): 596–603

Hunt, J., and Gauthier-Loiselle, M. (2010). “How Much Does Immigration Boost Innovation?” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 31–56

Kerr, William R. and William F. Lincoln (2010). “The Supply Side of Innovation: H-1B Visa Reforms and U.S. Ethnic Invention.” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 28(3), pp. 473–508

Manacorda, Marco, Alan Manning, and Jonathan Wadsworth (2012). “The Impact of Immigration on the Structure of Wages: Theory and Evidence from Britain.” Journal of the European Economic Association. Vol. 10(1): 120–151

Ottaviano, Gianmarco.I.P. and Giovanni Peri. (2012). “Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages.” Journal of the European Economic Association, vol. 10(1): 152–197

Peri, Giovanni and Chad Sparber (2009). “Task Specialization, Immigration, and Wages.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 1(3): 135–69

Peri, Giovanni and Chad Sparber (2011). “Highly-Educated Immigrants and Native Occupational Choice.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 50, No. 3

Peri, Giovanni, Kevin Shih, and Chad Sparber (2015). “STEM Workers, H-1B Visas, and Productivity in US Cities.” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 33 (No. S1, US High-Skilled Immigration in the Global Economy): S225–S255

Ruggles, Steven, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek (2015). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Sparber, Chad (2009). “Racial Diversity and Aggregate Productivity in US Industries: 1980-2000.” Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 75 (3): 829–856

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the New York Six Liberal Arts Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Selection Criteria

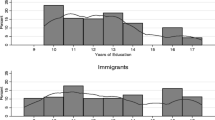

Importantly, Borjas [2014] employs subtly different selection criteria in constructing the dependent and explanatory variables in his regressions. Our selection criteria for defining skill values differs even further. Table A1 provides a clear summary of these differences.

Measuring Skills

We follow a procedure similar to PS09 and PS11 to calculate occupation-specific measures of the manual, communication, and quantitative skills used in each occupation. Resulting values represent percentiles: Namely, the percent of all workers using less of a given skill in 2010.

We begin with version 17 of the O*NET survey. This data source uses a scale of 1 to 5 to measure the importance of 52 separate abilities (or skills) required for each occupation defined by Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) codes. Since SOC codes vary slightly across years, we must develop a time-consistent occupation classification scheme. To do so, we use IPUMS-provided 1990 Census occupation codes (the occ1990 variable). We then calculate averages of O*NET scores within each occ1990 code.

Going through each of the 52 skills independently, we then rank occupations from highest to lowest skill values. Using 2010 ACS data on all workers (including men and women, natives and immigrants, high and low-education workers, etc.), we construct percentile values. For example, one O*NET variable records the importance of oral comprehension. Economists have a value of 0.45 for this variable, which we interpret as evidence that they used more oral comprehension skills than 45 percent of the entire labor force in 2010.

O*NET variables are narrowly defined. We instead construct broad aggregate averages of manual, communication, and quantitative skills using the O*NET variables identified in the main text. Since averages of percentiles do not strictly represent percentiles themselves, we perform the percentile procedure again on these averages. That is, we rescale the values to accurately reflect percentiles based upon the 2010 distribution of skills.

Importantly, these skill values only vary across occupation. They do not vary across individuals, time, nativity, gender, education, or any other factor. However, insofar that occupations correlate with observable characteristics of individuals, average skill values will vary across groups. This is what allows us to conduct regressions across education*experience*time cells when the dependent variable represents an average skill.

Table A2 provides a sense of extreme occupational skill values. The top panel displays the highest and lowest skill occupations for each skill measure among occupations overrepresented by high school dropouts (that is, the occupations for which the percentage of workers without a high school degree is greater than the percentage of workers without a high school degree in the overall workforce). The next two panels display the same information for workers with some college experience and workers with a graduate degree.

A large share of miners and cabinetmakers do not have a high school degree. However, O*NET recognizes no occupations requiring more manual skill, and hence they have a manual skill score of 1.00. Similarly, many door-to-door salesmen lack a formal degree. While these workers use few manual skills (they are in just the third percentile), they use more communication skills than 64 percent of the labor force.

As Figure 1 demonstrated, average skill values vary across education level. Among occupations overrepresented by graduate degree recipients, the most manually intense occupation (airplane pilots) uses more manual skills than just 68 percent of the labor force. Occupations with many highly educated workers are at the top end of the quantitative and communication skill distribution, however, while occupations dominated by high school dropouts are rarely in the top portions of those distributions.

Robustness of Peri and Sparber [2011]

PS11 uses short-run variation across individuals to estimate skill responses to immigration. It is a national approach that is identified by highly educated native-born individuals moving to new occupations when they witness an influx of immigration within their current occupation. We examine the robustness of their results. We use their CPS data and basic model specification, but we include all the standard fixed effects adopted by the Borjas cell methodology: That is, education group, experience group, education*experience, education*year, and experience*year indicators. As noted in the text, the results in our Table A3 are remarkably consistent with the baseline estimates in Table 6 of PS11.

Rate of Return to Skills

The regression model in equation (2) is used to estimate the education-specific rate of return to manual, communication, and quantitative skills, controlling for a series of indicator variables for foreign-birth, race, age, state of residence, industry of employment, weeks worked per year, and hours worked per year, plus fixed effects for education group, years of experience, year of observation, and their two-way interactions. Skill coefficients are displayed in Figure 3. Coefficients with standard errors are in Table A4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, E., Sparber, C. The Native-Born Occupational Skill Response to Immigration within Education and Experience Cells. Eastern Econ J 43, 426–450 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-016-0011-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-016-0011-z