Abstract

Following on from a previous paper advocating changes in the editorial processes of peer-reviewed journals, the present paper espouses the conduct of multiple local victimisation surveys as an affordable route to a pan-European crime science. Local surveys have a local impact which national surveys lack, and meta-analysis of survey results enable more general conclusions. The Latvian local survey reported in the chapter revealed wide inequality of victimisation at the individual level, an association between high rating of the seriousness of offences suffered, multiple victimisation at the individual level, and alienation from the police of some ethnic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper is the second of a pair with the same authorship. In the first, a case was made that the specification by a peer-reviewed journal of a required language of submission (usually English for the most prestigious crime science journals) disadvantages scholars fluent in languages other than the required language of submission. The consequences at the personal level for such scholars are underrepresentation in journals with high impact ratings, leading to fewer citations of their work, on which professional reputations are built. In brief, the probably unintended privileging of submissions in certain languages damages the careers of those not fluent in the language of submission of the intended journal outlet, which is usually English. The present situation also damages the discipline in a number of ways, notably the following.

-

1.

Extant literature feeds disproportionately on data from Anglophone communities.

-

2.

Insofar as criminogenic processes vary in different linguistic communities, crime reduction initiatives in non-Anglophone communities is likely to be based on misleading data.

-

3.

Key questions in crime science can only be answered by cross-national and cross-language comparisons.

The most ambitious of the revisions to journal processes advocated in our earlier paper took advantage of current and anticipated advances in machine translation services. Movement towards the long-term goal of a global crime science will inevitably involve such services. Machine translation has already enhanced the availability of current literature across language barriers. Google Translate now offers translations of text in 126 languages. Microsoft Word incorporates a ‘Translate’ option in its ‘Review’ menu. The organisation academia.com offers a range of languages in which papers can be downloaded. Some journals provide abstracts in more than one language.

There are both supply and demand obstacles to be overcome in the journey from where we are now to the realisation of a mutually comprehending community of crime science scholars. Most of the advances made possible by machine translation have served to satisfy demand rather than increase the diversity of supply. If scholars know what they are looking for and at least some keywords with which to navigate Google Scholar, they can locate and have translated material of interest to them. The major remaining problem is on the supply side. How can experts get their work published if they are not fluent in their preferred journal’s language of submission, comprehensible to readers with a range of language backgrounds and, crucially, reflecting the writer’s cognitions, not just her words? It is to these questions that our first paper’s recommendations were directed.

Whether or not crime science publication arrangements develop along the lines suggested in our earlier paper, translation services will revolutionise cross-language communication, both in the scholarly literature and in criminal justice exchanges. Our concern here is with the crime science literature. The dire state of affairs in respect of cross-language comprehension in interview rooms, custody suites and courts is evident to even a casual observer. The current flaws and consequent injustices in the provision and quality of translation services available to victims, witnesses and suspected perpetrators of crime is a Pandora’s Box waiting to be opened. The current writers intend to address these issues in future work. The sceptical reader need only talk to investigators, prosecutors or sentencers to get a sense of the problems. Cross-national comparison is obviously a valuable research approach for that topic.

Theory, language and literature

The first author is Latvian and currently working in the UK. The second is Latvian and works in that country. The third is UK trained and based but has experience working for the United Nations on comparative crime issues (see Pease and Huukila 1990). Their common experience is that the study of crime has taken different directions in different regions, to the point at which there are different sub-disciplines with different qualifications required for practitioners. In the west, the study of criminology–a social science, has little in common with criminalistics–a branch of limited criminal jurisprudence prevalent in the eastern world (Shatalov and Akchurin 2020). The study of crime is divided along lines of discipline allegiance, training and emphases. This makes the task of building a multi-faceted global crime science more than challenging. As the volume of scientific work increases with its potential for application, cross-language comprehension becomes ever more difficult as each locale evolves along the lines described above. Arguably it also becomes ever more important.

Our earlier paper was an attempt to set out ways in which the editorial processes of learned journals could be revised in ways which would help scholars not fluent in the few permitted languages of submission of the most prestigious journals. This paper considers the follow-on question: where such improvements in publication opportunities for those not fluent in the usual languages of submission to be realised, what would be the most profitable topics in respect of which parallel or collaborative studies to be undertaken?

For the sake of convenience and brevity, the focus is European rather than global. In the argument for serious consideration and analysis of data cross-nationally, there is a case for saying that Europe is the obvious starting point. Particularly after the incorporation of the accession states to the European Union, there is increased linguistic diversity coupled with policies (such as freedom of movement and labour across national boundaries) which make easy communication necessary. There are agencies (e.g., Customs Cooperation Council, Europol) which could benefit from an integrated pan-European evidence base on crime matters.

What is the current level of representation of eastern European scholars and topics in the leading journals? Considering such crime science journals with the word European in the title, if our contention about the favouring of English in the publication process were correct, this would result in low representation of scholars from Eastern Europe, where levels of fluency in English are lower. That is not the only possible reason for low representation, but it is a plausible speculation. We first checked the proportion of eastern European authors and publications about eastern Europe in three leading journals, the European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, the European Journal of Criminology and Crime Prevention and Community Safety. In 2021 the first-named Journal featured thirty one papers by sixty-two authors. One article was expressly about an eastern country and only five authors were affiliated to universities in eastern Europe.Footnote 1 in the same year the European Journal of Criminology carried forty-seven contributions by ninety-seven authors. Seven of the contributions were expressly about eastern Europe. Eight of the authors were affiliated to eastern universities. Crime Prevention and Community Safety carried 28 publications by sixty-two authors that year with zero being expressly about eastern Europe and just two authors affiliated with an eastern university. Our anticipation of low representation of Eastern European scholarship in the literature would also be evident in fewer citations of work of Eastern European origin in the same journals.

Looking at the numbers of citations per publication, articles about Eastern Europe were referenced a lot less by other authors, suggesting that they are less accessible (or of less interest) to crime scientists generally. This is also consistent with (but not determinative of) the marginalisation of Eastern European scholarship in the journals where one would be most hopeful of its absence.

We make three assumptions. First, despite difficulties of geography and language, there is an appetite for pan-European comparative research. We acknowledge and applaud the achievements of European scholars who already collaborate across national and linguistic barriers (see Beck et al. 2006; Mawby et al. 1997; Weitekamp and Kerner, 2012). Second, assuming we want crime science to be useful, there has to be a symbiotic relationship between cross-national and intra-national research. To spur political and police leadership into action, it must be demonstrated whether global or national patterns are reproduced locally, and the implications of such similarities and differences. Third, there are some general truths about crime which can only be established by cross-national and cross-language comparisons.

Evidence consistent with the first assumption is, as noted above, to be found in the number of cross-national and pan-European collaborations to be found in the literature. The second assumption is based on many years’ experience of the deployment of the ‘not invented here’ reason for inaction of local politicians and police chiefs. Even within England and Wales, between-force variation in data acquisition and management is substantial, even where the advantages of easy cross-force comparison are clear. As to the third assumption, we briefly identify the global crime drop as demanding the most diverse data sources possible.

A starting point: suggestion and justification

Victim surveys provide the best available information source about the nature and distribution of crime. They provide the baseline against which metrics of the operation of policing and criminal justice are properly compared. They also provide the richest source of immediate implications for action. Crime events occur when they do, victims can provide most detail of what happened. For some offences such as burglary and embezzlement perpetrators know more but are not available to be interviewed. All data about events and decisions subsequent to the crime event itself are heavily filtered in different ways, depending on public attitudes to the police, investigative effort and priorities and sentencing principles. In the most thorough analysis of attrition in criminal justice of which the writers are aware (Ramsey 1999) it was found that in England and Wales, of offences suffered, only half were reported to the police, of which only six in ten were recorded by them, of which only one in four had a perpetrator identified, of whom only one in four were convicted of the offence. Any criminological study focusing on convictions addresses only 2% of the events which gave rise to the process. Victim accounts are the closest we can realistically get to understanding what happened. In the UK, the centrality of victim reports to an understanding of crime problems has been recognised to the point where (in 2012) crimes known to the police ceased to be granted the status of official statistics, whereas the responses in the national victimisation survey (CSEW) remained. Large scale victimisation surveys are difficult to fund and organise. Justification of such funding is politically difficult. Multiple small sample surveys in different locations (For example, in England, see: Bottoms, Mawby and Walker 1987; Sparks et al. 1977; Young 1988) proved valuable in identifying neglected crimes and local crime patterns, and were influential in the decision to fund a periodic national survey (Mayhew and Hough 1992). They consequently serve as a consciousness raiser which may create a demand for subsequent larger surveys which allow greater statistical confidence in the results.

Meta-analysis can be brought to bear to combine data from small surveys to yield a composite picture of crime patterns and trends. Implicit in the foregoing is their local credibility of local data. Whatever statisticians say (correctly) about confidence intervals, local data is generally accepted more readily.

In summary, our contention is that small scale local victim surveys are both valuable in their own right as a rough guide to local crime issues and as a consciousness raising bridge to fully-fledged national surveys.

A Latvian local victimisation survey

We have earlier rehearsed the uses of local surveys and now present an account of one such survey undertaken in Latgale–the eastern region of Latvia bordering Russia, Belarus and Lithuania, and its principal city of Daugavpils. The focus extends to the experiences with the police, being a factor triggering the criminal justice process. Because the dynamic and history of police-public relationships in Latvia is complex, care and sensitivity are needed in survey design. The circumstances in which force may be used are of great importance. Evidentiary requirements for enforcement differ, (especially for cybercrime, where victims and perpetrators may be located in different jurisdictions). Historic conflicts have at many times and places led to citizen distrust. Criminal justice agencies may be viewed as corrupt, petty, and bureaucratic. Citizen views will likely vary by social group, ethnicity, gender and age. The picture is especially fraught when the police are seen as agents of the state rather than servants of the public, whose reluctance to engage with social research in Eastern Europe can be attributed to fear of scams, as well as lack of experience with social researchers, given surveys and other social research methods are more associated with journalists than academics. Research about crime and the criminal justice system is also often avoided, as potential participants worry about personal safety and potential exposure of their opinions to the authorities. Despite much anti-corruption work having been done, public trust remains low. These factors are obstacles to, but paradoxically give reasons for, the emphasis on the crime event. What follows seeks to provide an illustration of western sociological and criminological perspectives modified and tested with Latvian data. As noted above, the reverse process is equally important so as not to impose an inappropriate Western mindset. The choice of starting as described above is simply that the relevant research instruments exist primarily in the West. We wish that it were not so. The topics abstracted from CSEW in the work reported below are as follows.

-

(1)

Unequal distribution of crime and key victim characteristics

-

(2)

Crime seriousness judgements of the victim

-

(3)

Reasons for non-reporting of victimisation to the police

-

(4)

Fear of crime and other emotions experiences attendant on victimisation

Methodology

The goal of the study was to pose questions to a Latvian sample similar to those asked in commonly used Western datasets such as CSEW (Crime Survey for England and Wales) and ICVS (the International Crime Victimisation Survey). Of particular interest, due to the quantity of existing research on the topics and because of the obvious practical implications arising from such issues, were as follows.

-

1.

the sociodemographic characteristics of victims and their victimisation rates,

-

2.

victim experiences associated with victimisation incidents, and

-

3.

markers indicating cooperation (or its lack) with the police.

Adjustments of questions were made in order to take into account cultural and linguistic differences and was carried out with the help of fellow Latvian and Russian speakers, to ensure the questions were appropriate to the research environment and are easily understood by the participants. For example, the housing styles in Latvia differ from those examined by CSEW, so a question about residency only had two simplified options from which to choose—detached housing or flats. The survey instrument was created in both Latvian and Russian and disseminated via paper copies in person in 2018 and 2019 with researcher present and available to clarify the questions and answer categories, and in an electronic format in 2021 with a total sample of 322 respondents, spread equally across the years. The surveys were completed in full with less than 3 per cent of surveys having missing responses. The sample was diverse in terms of gender, age, citizenship, marital status and a number of sociodemographic characteristics but given the overall scepticism towards data collection, it was a challenging task to find older male participants. The final sample comprised 31% male and 69% female respondents and represented ages from 18 to 95. 66% of the sample were married, 54% were Russians, 19% Latvians and 27% of another ethnicity. 68% had Latvian citizenship. The national and ethnic makeup of the sample is clearly not representative of Latvia as a whole, as Latgale represents a melting pot drawing its population from Russia, Belarus and Lithuania. Over 70% of the participants came from Daugavpils, Latvia’s second largest city with a large population of Russian people and other ethnicities. Daugavpils is also known as Europe’s most Russian-speaking city and of the sample only 45 respondents chose to complete the survey in Latvian. Indeed, if the data collection was carried out throughout the country, many of the findings presented further in this paper would not be replicated, as the local cultural differences (eventually translating into local policing initiatives) in Latgale and Daugavpils are specific to the anthropological makeup of the area, shaped by historical and political events, voting preferences and representational issues.

Analyses

The study reported here looks at existing victimisation research carried out using large scale victimisation datasets in the UK and internationally and attempts to make some very tentative inferences about similarities and differences with Latvian experiences. Four key themes, as identified earlier, are explored in these analyses. First, inequality of victimisation and the victim characteristics associated with higher victimisation rates are examined. Second, we review Latvian perceived seriousness of offences. The third theme concerns interaction between victims of crime and the police, in particular the reasons for non-report of crimes and other methods of dealing with victimisation. Finally, a topic overlooked not just in Eastern Europe but across the world–emotional responses to victimisation are explored to see, whether theories about fear of crime hold in the Latvian context.

Inequality of victimisation

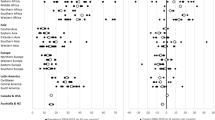

Research from the UK utilising CSEW data has consistently shown that a very small proportion of people experience an overwhelming proportion of total victimisation. The proportion of total victimisation suffered by the most victimised decile increased to over 70% between 1992 and 2012 (Ignatans and Pease 2015). Indeed, approximately 27% of vehicle crime 33% of property and 52% of personal victimisation was experienced by the 1% most victimised in 2012. The same research showed that as little as 30 per cent of the total population were victimised at all over the course of a year. Research from the ICVS has shown that the same rough distribution applies to most of the participating Western countries between the years 1992 and 2000 with as much as 22% of vehicle, 48 of property and 36 of personal victimisation was experienced by just the top 1% of most victimised (Pease and Ignatans 2016). Unsurprisingly, the ICVS, despite its ambitious title, is also Anglo-centric and includes mostly countries from Western Europe and from countries where English is the mother tongue. In the Latvian data analysed here, the distribution of victimisation appears to be slightly more equal with 59% of vehicle, 61% of property and 72% of personal crime experienced by the top 10% of the total sample and as much as 31, 16 and 15 per cent respectively by the top 1% of the respondents (Fig. 1). The proportion of victims in the sample is also higher, with 53, 61 and 64 per cent of respondents reporting vehicle, property and personal victimisation respectively. Despite the slightly less unequal distribution compared to the CSEW and ICVS data from Western countries, the patterns of unequal distribution of victimisation are substantial enough for the western practical concerns of repeat victimisation to be useful in Latvia.

Despite the unequal distribution of victimisation, average victimisation numbers experienced by the most victimised in much of Western data have been steadily on the drop, with the absolute victimisation of the most victimised decile declining from 7.5 victimisations per victim in 1992 down to 3.2 in 2012 (Ignatans and Pease 2015). In many ways, this can be viewed as a fortunate side of the otherwise unfortunate situation–even though the distribution of victimisation is skewed, on average the suffering amongst victims as a whole has diminished. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for Latvian people, as the average number of vehicle victimisations experienced by a top decile victim in the dataset was 11, for property and personal crimes the numbers were 9 and 15, respectively, and in total a victim the in top decile reported over 31 victimisations over the last year (Fig. 2.). Without data to compare this with previous years we cannot comment on trends over time, but the base number itself is high enough to warrant concern.

Personal and sociodemographic characteristics of repeat victims have also been consistently examined in the relevant literature with CSEW data showing that factors such as younger age, fewer children in the household, shorter length of residence in the same area and address, as well as being witness to criminal incidents, amongst other factors, are the distinguishing statistically significant characteristics between repeat victims and others. This has not changed much over the last 30 years (Ignatans and Pease 2015). In the Latvian context many similarities can be found. Being younger, having fewer children as well as being witness to crime have also been the factors associated with a higher number of experienced victimisations, as has unemployment, fewer cohabiting adults and having Latvian citizenship (there will be more discussion on ethnicity and citizenship in the remainder of this paper). Length of time resident in an area and address were only slightly associated with higher personal victimisation but considering the self-sufficient lifestyle and lower frequency of changing address, those factors were too uncommon in the sample for them to reveal their relevance to victimisation patterns (Table 1.).

Crime seriousness and the victim

Not all crimes are equal in their impact on their victims. Nor are they equal in their costs to the victim and the state. What is the best way to identify which crimes should extract greatest effort to prevent or solve? Crime seriousness is a concept rarely explored in depth, and often oversimplified for the purposes of either bureaucratic application or public consumption. Viewing crime seriousness from the victim’s perspective appears to be the most obvious and straightforward way that allows a first-hand assessment of the offence, not clouded by unnecessary refinement.

Previous studies which have explored crime seriousness from the victim’s perspective have shown that victims of single incidents overwhelmingly report crimes of lower seriousness than repeat victims. In CSEW, crime seriousness is judged on a scale between 1 and 20. On average a victim of single incident would report a score of 5.1 and repeat victim a score of 6.5 (Ignatans and Pease 2016a, b). CSEW-based research looking at crime seriousness by victims’ ethnicity has raised important practical considerations–victims from ethnic minorities are likely to judge most of victimisation as more serious than the native population (Los et al. 2017) with some interesting outliers. South Asian victims were likely to accept harassment-related victimisation in the workplace as part and parcel of their life, while Eastern European victims rated chipped teeth arising from an alteration as very serious but broken bones and nose as much less serious (as the former requires funds to resolve while the latter is covered by the state) (Ignatans et al 2016).

A Latvian victim with a single victimisation incident experienced in the past year reported an average seriousness rating of 11.11 (s.e. 1.77) while a repeatedly victimised respondent’s rating was 13.3 (s.e. 0.45), demonstrating that the issue of increased crime seriousness perception amongst repeat victims is even more apparent in Latvian data. A distribution of crime seriousness scores as reported by Latvians is as set out below (Fig. 3). Over 60 per cent of vehicle crime victims rated their incident at 20 with over a third doing the same for personal and total crime. Only 11 per cent of property crime victims selected 20 to describe their incidents with most choosing the score of 10 for that crime category.

Distribution of crime seriousness in the population is just as much of a concern as is distribution of victimisation itself. The burden of seriousness is likely to be carried by the few. CSEW asks its respondents to evaluate as many as five of their most serious victimisation incidents and provide a score for each and CSEW data has consistently shown that top decile of the most victimised has experienced over 45% of aggregate crime seriousness (Ignatans and Pease 2015) with an average crime seriousness score of over 50 per household. While our Latvian questionnaire did try to emulate much of the structure of CSEW, we did not ask our participants to go into detail about more than one of their victimisations, so they rated only the most serious incident experienced in the last year. This meant that the top decile, i.e. the 10% most victimised experienced only 15.7% of aggregate victimisation with an average seriousness score of, of course, 20. This might seem low, but the same proportion was also experienced by the 9th and 8th decile (as the average score of 20 was chosen by 31 per cent of respondents). So, roughly 47.1% of total crime seriousness is experienced by the victims reporting the highest crime harm rating of 20, meaning incidents perceived as most serious account for almost a half of aggregate seriousness.

Non-reporting to the police and reasons for it

Police cars in the USA have the legend ‘to serve and protect’ on their doors. They notionally exist to help the public in the case of emergency, amongst many other reasons. Whatever those other reasons, if the public do not report crime to the police, the chances of police a) finding out about the crime and b) offering help are slim to none. Groups of people cooperating with the police the least always need to be identified and measures need to be taken to improve the rapport between the two parties and ensure effective communication, if police are to be able to do their job. Using CSEW data it was shown that ethnic minorities which lack representation in the criminal justice system and have least trust in the system are least likely to report their crimes to the police (Los, Ignatans and Pease 2016a, b). Unfortunately, the same groups of people viewed their victimisation incidents as more serious, as mentioned before. Over a half of Asian immigrants—the group reporting victimisation to the police the least—also believed that in the overwhelming majority of cases the police could not have helped (35%) or would not have bothered to help them (21%) with similar beliefs shown amongst African immigrants.

Without a long discussion about the lack of representation of ethnic minorities in the police forces in Western countries and the impacts that has on the levels of trust in the police, a Latvian situation must be contextualised before statistics are presented. Latvia, and in particular Latgale, where this research took place, has a large population of non-citizens, people without a citizenship of any country who, amongst other restrictions, are not able to work within the police. Neither are citizens of other countries. There are roughly 200 thousand of non-citizen status, 50 thousand Russian citizens and 45 thousand citizens of other countries in Latvia as of 2021 (Latvian Population Register, 2021) as well as 1.8 million Latvian citizens. The populations of non-citizens and Russian citizens are unequally distributed, with Daugavpils, the city where most of the surveys were carried out, being populated by 53.6% who identified as Russian and only 19.8% as Latvia (Daugavpils Census Data 2011), so the attitudes towards the police found in our survey are not likely to be representative of Latvia as a whole.

A number of analyses were carried out to explore reporting to the police and the reasons for not doing so, with one comparing citizens and non-citizens, and the other looking at the ethnic identity of the respondent. A person who identifies as Russian may have Latvian citizenship through naturalisation, and a person who has no citizenship may identify as Latvian if they believe they belong to that identity, so comparisons are needed. Respondents were asked to state whether they reported crime to the police and if so, to rate their experience with the police from 1 to 20. Those who did not report crime to the police were asked to choose one of the four reasons for not doing so and to rate their expected cooperation with the police, if they were to report it.

Table 2 shows that there is a vast discrepancy between the reporting of crime to the police and non-citizens and people of ethnicity other than Latvian or Russian are reporting crime much less frequently and, in the case of ethnic minorities, rating their experiences with the police much less favourably. The reasons for non-reporting also range, with citizens and people of Latvian ethnicity believing that police could not have helped, while non-citizens and people of Russian and Other ethnicities finding other ways to deal with the victimisation (about this further on). Expected cooperation with the police amongst non-reporters was overwhelmingly low, with a lowest score of 1.2 (out of 20) given by people of Russian ethnicity.

Emotions experienced after victimisation

Despite heavy amounts of rhetoric about fear of crime and it’s impacts on victims from the state funded research and media, independent studies have proven that it is annoyance and anger that dominate the emotional response amongst victims of crime (Ignatans and Pease, 2019). For many offences, a response of anger dominated fear even in cases where the incident was rated as very severe: an inconvenient truth for any politician favouring a police state, given both of those emotions say “fight” and not “flight”. Similar findings in the Latvian context would have clear policy implications, especially when juxtaposed with the findings from the previous section, where an overwhelming majority of people from groups least likely to report crime to the police have had other ways of dealing with the crime, be it revenge, vigilantism or any other non-official methods.

Mirroring the CSEW question about the emotions experienced, the respondents in the Latvian survey were asked to report which emotion (s) they experienced after victimisation. The results are displayed by victimisation status, crime severity judgements, citizenship and ethnicity. Table 3 shows two key points, the first one being that anger dominates the emotional responses in most analyses, and the second that ethnicities other than Latvian overwhelmingly experience “fight” emotions rather than the “flight” emotions experienced by Latvians. An argument can be made that such emotional response explains the desire to find other ways to deal with crime themselves, rather than pass it onto the police.

Conclusions and discussion

Noble attempts at collaborative enterprises to generate cross-language communication have struggled. The most ambitious, the International Crime Victimisation Survey, eventually failed (Rodenas and Doval, 2020) but accurately identified the most profitable starting point for such efforts, the crime event itself, rather than the criminal justice process. Hence our illustrative example of the appropriate growth point for such research, the surveying of crime victims. Nationally representative victim sampling is expensive and difficult to organise. It is argued that local surveys are a realistic way of proceeding, primarily because local surveys have local relevance which national surveys lack. This is notable in Latvia, and maybe the other Baltic States, where the ethnic composition of different regions or cities may vary markedly. Meta-analysis of local surveys combined with wide use of machine translation services to aid accessibility of survey results represents a viable route towards a global crime science.

There are four key points made in the analyses of the Latvian survey comprising the second part of this paper.:

-

(1)

Victimisation in Latvia is unequally distributed, and super victims are easy to identify.

-

(2)

Reported crime seriousness ratings are much higher for repeat victims (of whom there is plenty) further supporting the first point and requiring intervention on a local level.

-

(3)

Ethnic and national groups not represented in the police forces are less likely to cooperate with the police and trust them but may find their own ways to deal with crime.

-

(4)

Same groups of people will be more angry than afraid about their victimisation incidence, further explaining the third point.

The final conclusion relates to our ambitious initial concern, namely that insights can be gained by integrating the continent of Europe’s scholarship about crime. We need to communicate to gain usable insights. We have chosen to apply a research approach to Latvian data from a perspective which is novel in Latvian scholarship and found differences and similarities which have implications for policy. It is these circumstances which led us to proceed as we did. Conducting analyses of Western data using a Latvian approach (for example, police investigative priorities) are no less valuable, just not where our experience lies. Seeing the crime story as a whole, from criminogenic environments to penal efficacy, and from different cultural perspectives, is an enterprise worth pursuing.

Notes

Definition for Eastern Europe is highly contested and in this context is taken from the International Criminal Court that includes the Baltic states.

References

Beck, A., Y. Chistyakova, and A. Robertson. 2006. Police reform in post-soviet societies. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bottoms, A.E., Mawby Rl, and M. Walker. 1987. A localised crime survey in contrasting areas of Sheffield. British Journal of Criminology 27: 125–154.

Daugavpils census data (2011), Oficiālās Statistikas Portāls. https://stat.gov.lv/en/statistics-themes/population/private-households/other/3481-private-households-and-families-census

Ignatans, D., & Pease, K. (2016b). Taking crime seriously: playing the weighting game. Policing: a Journal of policy and practice, 10(3), 184–193.

Ignatans, D., Roebuck, T. Nomikos, E. (2016). Differences in perceptions of crime seriousness amongst immigrant populations and their impact on levels of crime-reporting. Crime Data Users Conference, London, UK

Ignatans, D., and K. Pease. 2015. Distributive justice and the crime drop. In The Criminal Act, 77–87. London: Palgrave.

Ignatans, D., and K. Pease. 2016a. On whom does the burden of crime fall now? Changes over time in counts and concentration. International Review of Victimology 22 (1): 55–63.

Los, G., D. Ignatans, and K. Pease. 2017. First-generation immigrant judgements of offence seriousness: Evidence from the crime survey for England and Wales. Crime Prevention and Community Safety 19 (2): 151–161.

Mawby, R.I., Z. Ostrihanska, and D. Wojcik. 1997. Police response to crime: The perceptions of victims from two Polish cities. Policing and Society 7: 1–18.

Mayhew, P., and M. Hough. 1992. The british crime survey: The first ten years. International Journal of Market Research 34 (1): 1–15.

Pease, K., and Hukkila, K. (1990). Criminal justice systems of Europe and North America. Helsinki: HEUNI.

Pease, K., and D. Ignatans. 2016. The global crime drop and changes in the distribution of victimisation. Crime Science 5 (1): 1–6.

Ramsey, M. 1999. Digest 4: Comprehensive information of crime and justice in England and Wales. London: Home Office.

Ródenas, C., and A. Doval. 2020. Measuring crime through victimization: Some methodological lessons from the ICVS. European Journal of Criminology 17 (5): 518–539.

Shatalov, A.S., and A.V. Akchurin. 2020. On the need to develop professional competences in criminal procedure and criminalistics in corrections officers of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia. Пeнитeнциapнaя Нayкa 14 (4): 570–575.

Sparks, R.F., H. Genn, and D.J. Dodd. 1977. Surveying Victims. London: John Wiley.

Weitekamp, E., & Kerner, H. J. (Eds.). (2012). Cross-national longitudinal research on human development and criminal behavior (Vol. 76). Springer Science & Business Media.

Young, J (1988). Risk of crime and fear of crime: a realist critique of survey-based assumptions. In Maguire M, and Pointing J (Eds), Victims of crime: a new deal. Milton Keynes: Open University Education Enterprises.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the research presented in this article comes from 2021/01 Daugavpils University’s Research Grant scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ignatans, D., Aleksejeva, L. & Pease, K. Global crime science: what should we do and with whom should we do it?. Crime Prev Community Saf 25, 386–400 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-023-00188-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-023-00188-y