Abstract

A lot of previous research has focused on the public’s intentions to support organizations based on their actions related to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). However, people’s perceptions of CSR during challenging times are yet to be fully explored. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the relationship between the public’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to CSR during uncertain times (i.e., a global pandemic). A total sample of 407 responses were collected during the first wave of the global pandemic across two countries, representing the European and African continents. The results show that in challenging times, negative emotions appear to fade into the background and do not play a significant role. Interestingly, cognitive evaluations (mind) are the strongest predictors of perceptions of CSR, while positive emotions (heart) are the key drivers of behavioral response toward the company. Theoretical and managerial implications are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel”

Maya Angelou.

There is a growing trend of companies acknowledging their role (albeit voluntary) in society during adverse times. Anheuser-Busch (owners of beer brands like Budweiser and Stella Artois) are well known for their emergency response plans, such as the distribution of emergency drinking water to fire departments working on disaster relief efforts (Anheuser-Busch, n.d.). During the global Covid-19 pandemic, many organizations initiated various responsible activities, driving positive societal change (RepTrak 2020). ‘The Ventilator Challenge UK Consortium,’ led by Airbus, brought together manufacturers from different industries to help the production of medical ventilators to support the NHS in the UK (Ventilator Challenge UK 2020). Other examples include companies involved in the manufacture of hand sanitizers (e.g., Diageo, L’Oréal), the provision of free services and technical support to healthcare and education (e.g., Zoom, EE), or the donation of money to relief efforts (e.g., Facebook, Google). Although this type of activities during times of uncertainty are likely to generate positive reactions among the public and favor their support toward the company, whether or not individuals still consider CSR essential during adverse events is unknown.

Despite these growing efforts of companies to be more responsible during uncertain times, some companies appear to give more importance to specific business functions, whether it is about providing the best possible products, focusing on the organization’s survival, or generating economic stability. For instance, during the first six months of the pandemic, Berkshire Hathaway reported $56 billion in profit, while more than 13,000 employees were laid off in one of its subsidiaries. Similarly, Walmart reportedly paid more than $10 billion to their investors, while 1200 corporate office employees were dismissed (The Washington Post 2020). Such strategies could lead to the public reacting negatively to the organization’s CSR, as they might believe CSR loses significance during a period of crisis. Or, on the contrary, this might not have an effect on a company, as the public may also see CSR as secondary during uncertain times.

The intention to support a company based on its CSR activities has been widely explored in the literature (Vlachos et al. 2013; Almeida and Coelho 2019; Hofenk et al. 2019; Achabou 2020). Although most studies support a linear (positive) relationship between perceived CSR and supportive behavioral intentions, Sen and Bhattacharya (2001) show that this relationship is not as simple as it may appear. In fact, under certain conditions, perceptions of CSR could decrease the public’s intention to support the firm (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Kim and Lee 2015). This may be related to specific CSR initiatives companies engage in, that evoke rather negative reactions from the public, including skepticism and disbelief in the company’s true motives (Rim and Kim 2016; Moscato and Hopp 2019; Achabou 2020). Thus, we argue it is increasingly important to understand how people evaluate a company’s CSR responses during uncertain times (both at emotional and cognitive levels), and how those evaluations impact their perception of the company’s CSR and, ultimately, their level of support toward the organization. As “people will not forget how companies made them feel,” a better understanding of the dynamics mentioned above will allow organizations to proactively design and address their responsibilities while experiencing adverse events. This is relevant because the way individuals evaluate those responses and behave as a consequence might be different to how they would evaluate a company’s behavior in more stable conditions (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001).

This study responds to recent calls to shed more light on the effects of the public’s reactions toward CSR, particularly in the events of adversity (He and Harris 2020; Fatma et al. 2022), and aims to explore the relationship between the public’s perceptions of CSR and their behavioral intentions toward the company, considering the role of cognitive (mind) and emotional (heart) evaluations of the company’s activities during uncertain times. A plethora of studies has favored cognitive evaluations of CSR activities (Lee et al. 2013; Kim and Lee 2020; Fatma et al. 2022) over emotional ones, which are challenged in this study, while proposing to consider both dimensions simultaneously.

First, our study contributes to the CSR literature and advances current knowledge by simultaneously considering the role of cognitive and emotional evaluations of company’s CSR response, as critical drivers of perceived CSR (Xi et al. 2019; Ooi et al. 2022); highlighting how mind and heart may vary depending on desired outcomes. Second, our research contributes to the theory on emotions and CSR by offering a counter-intuitive finding in relation to negative emotions, as those have not been found to result in reduced desired outcomes, as suggested by previous research (e. g, Roseman and Smith 2001; Du and Fan 2007; Barclay and Kiefer 2014; Sung et al. 2023). Finally, this study contributes to knowledge by unpacking a (partially) mediating role of perceived CSR in the times of uncertainty. Overall, our study contributes to existing knowledge by offering a nuanced understanding of individuals’ evaluations of companies’ CSR responses and subsequent behavior during uncertain times, which may be different to those experienced under more stable conditions.

In the next sections, we first briefly review relevant literature in the areas of CSR, particularly looking at how emotional and cognitive evaluations may impact perceived CSR and subsequent behaviors. We then continue by explaining the rationale behind our chosen methods and present the results of our quantitative study. The discussion of the results follows, highlighting our contributions. The paper concludes with the limitations of our study and directions for future research.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Perceived CSR in Uncertain Times

CSR has gradually grown into an essential part of corporate strategy in contemporary organizations (D’Acunto et al. 2020). The significant influence from increasing societal expectations toward companies has forced firms to pay more attention to CSR activities (He and Harris 2020; Shin et al. 2021). Companies tend to focus on CSR, seeking for various benefits for the company (e.g., improved image and reputation, employee retention, support from customers—see Walsh et al. 2009; Fombrun et al. 2015), for society and the environment (e.g., improved relationship with the community, reduction of CO2 emissions, and contribution to sustainable development—see Dyllick and Muff 2016; Schons and Steinmeier 2016). As a result, successful CSR has increasingly demonstrated its positive influence on the public’s support toward organizations (Hofenk et al. 2019), as perceptions of CSR seem to play an important role in the formation of supportive behavior toward the company (Brown and Dacin 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). It is agreed that perceived CSR is an individual’s response to CSR initiatives and activities a company engages in (Kim and Bae 2016).

Even though most studies have found benefits of positively perceived CSR to organizations, one should acknowledge that CSR can be viewed as a dynamic concept (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Tetrault Sirsly and Lvina 2019), which may be challenged in a drastic change of context (i.e., a global pandemic—see He and Harris 2020). Despite financial pressures, many companies have proactively participated in various CSR activities during the pandemic, especially those that can deliver immediate assistance against the virus. Companies’ CSR practices appear to result in even stronger affiliation with the public, as they witness dedication from the organization (He and Harris 2020).

However, what has been largely overlooked is how a specific CSR response (i.e., evaluations of thereof) during times of uncertainty can influence the public perception of company’s CSR. For example, the UK sportswear brand Sport Direct refused to close their stores during the first wave of the pandemic, claiming they were an essential business (while all non-essential businesses had to stop trading). Despite an eventual U-turn from the CEO to shut the stores, the company was largely criticized for being irresponsible toward their employees (BBC 2020). In the US, employees from several companies (e.g., Amazon, Instacart) went on strike due to lack of protective gear available at work (New York Times 2020). The reaction (or lack of) from these organizations not only affected those suffering first hand (who mainly felt fear), but also led to public protests and boycotts. From these examples, it is evident that the public’s reactions to a specific initiative during the pandemic could lead to negative behavioral responses toward companies. A possible explanation is that during challenging times, people tend to be more vulnerable and uncertain, and their expectations may rise and change especially when it comes to CSR (Mahmud et al. 2021).

It is thus important to unpack the role of people’s reactions to the pandemic-related CSR activities. One way of doing this would be to explore public’s perceptions of CSR, by specifically exploring evaluations of CSR activities in terms of their emotional and cognitive elements (as done in this study). This follows the argument by van der Berg et al. (2006) and Keer et al. (2014), who suggest that there is merit in exploring cognitive and affective components of evaluations individually.

Emotional Evaluations of CSR Activities

Emotions are ‘a form of affection involving visceral responses that are associated with a specific referent, and result in action’ (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001, p. 83). Building on the Appraisal Theory of Emotions (ATE), individuals’ evaluations of a situation or event act as a catalyst of eliciting emotions (e.g., see Lazarus 1991; Roseman and Smith 2001; Scherer 2009; Ellsworth 2013; Roseman 2013; Moors 2014; Sung et al. 2023). As a result, individuals’ emotional evaluations are triggered by an appraisal (i.e., a judgment) of an event or an issue, and their emotional response could either be positive and/or negative (Joireman et al. 2015).

In the context of CSR, individuals tend to experience emotions based on the company’s specific actions, which may for instance relate to products and services or support for local communities (Dawar and Parker 1994; Lange et al. 2011). Hillenbrand et al. (2020) suggest that both positive and negative emotional evaluations can help explain individuals’ reactions. This phenomenon could be explained through the lens of the ATE, which (as explained above) suggests that people may react differently (positively vs negatively) to the same issue (i.e., a company’s CSR response to a crisis). For example, based on the ATE, one may argue that people's emotional evaluation of a company’s CSR response can trigger changes in how they view the overall company’s CSR and behave as a result of it. While negative emotions may cause people to act in ways that would allow them to distance themselves from the business or its CSR initiatives, positive emotions can encourage supportive actions (Maon et al. 2019). We thus propose that emotional evaluations of a company’s CSR response can play an important role in explaining how people perceive the overall company’s CSR (Newell et al. 2007; Ooi et al. 2022) and their subsequent behavior.

Even though the relationship between emotions and CSR has not been given much importance in the literature (Xie et al. 2019), the relevance between the two phenomena is highlighted in previous research. Andreu et al. (2015) suggest that emotions play a vital role when evaluating CSR activities, in particular those related to employee support (e.g., safety, job security). Xie et al. (2019) argue that positive emotions (i.e., gratitude) have positive effects on subsequent supportive behaviors, such as word of mouth (Markovic et al. 2022).

Interestingly, the CSR literature has been mainly focusing on positive generic emotional states (i.e., positive mood) in relation to its impact on perceived CSR (e.g., Liu et al. 2021). Although we believe that there is merit in focusing on positive emotions, and assume those would lead to positive perceptions of CSR, following Izard (2013) and Tellegen (1985), emotions essentially fall into two categories of positive and negative and, therefore, both should be considered when exploring the effects of specific company’s activities on perceptions of CSR.

Provided that the CSR literature is rather modest on the effect of negative emotions on CSR, there is evidence from related disciplines that negative emotions could lead to a decrease in desired outcomes such as satisfaction (Du and Fan 2007), attitudes (García‐De los Salmones and Perez 2018), or recommendation behaviors (Hosany et al. 2017). We thus assume that negative evaluations of the response to the pandemic may hinder perceived CSR. However, this notion is yet to be tested in a scenario when people are generally experiencing negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger, sadness—see Metzler et al. 2022), as it might happen during uncertain times.

As a result, we acknowledge that a company’s CSR response in a crisis may elicit conflicting interpretations and emotions, which may affect how a company's CSR is perceived (García‐De los Salmones and Perez 2018). This accords with the ATE (Roseman and Smith 2001; Sung et al. 2023), suggesting that individuals might in fact experience both positive or negative emotions toward a company’s responsible activities, because it is the appraisal of the company’s CSR efforts that determine the emotions individuals will feel.

The above led us to proposing the following hypotheses:

H1:

Positive emotional evaluations of a company’s CSR response are positively related to perceptions of CSR.

H2:

Negative emotional evaluations of a company’s CSR response are negatively related to perceptions of CSR.

Cognitive Evaluations of CSR Activities

In line with MacKenzie and Lutz (1989, p. 49), we consider cognitive evaluation as ‘a disposition to respond in a favorable or unfavorable manner’ to an event or information (see also Hillenbrand et al. 2020). The literature provides strong evidence on the link between positive cognitive evaluations and supportive intentions (Doll and Ajzen 1992; Walsh et al. 2011). For instance, positive evaluations of a product information may translate into more probable intentions to engage with that product (Lu et al. 2014), while health-related behaviors appear to be triggered by cognitive evaluations (particularly, when comparing with affective evaluations) (Keer et al. 2010).

The extant CSR literature has widely acknowledged the role of cognitive evaluations of various CSR-related activities. Individuals evaluate companies’ CSR through cognitive processing of information they receive about the company's activities and practices, which are a large part of how people react to CSR (Jones 2019). For instance, Lee et al. (2013) argue that cognitive evaluations of CSR capability are a significant (positive) predictor of perceived CSR. Kim and Lee (2020) further suggest that high consumers’ cognitive evaluation of CSR fit (alignment between the company’s operations and their CSR practices) improves their perception of CSR authenticity. Building on the existing research on the effects of cognitive evaluations on subsequent behaviors, one may argue that individuals who have favorable cognitive evaluations of a company’s CSR response are more likely to see the overall company’s CSR more favorably and provide greater support for the company (Bhattacharya and Sen 2004; Wagner et al. 2008; Dastous and Legendre 2009; Stanaland et al. 2011).

Previous studies mainly focus on cognitive evaluations of generic CSR activities, pursuing a rather broader view (Lee et al. 2013; Kim and Lee 2020). Interestingly, Choi (2020) suggests that cognitive evaluations of CSR activities increase when consumers are not involved with the cause the company is supporting. We believe that there may be other yet unexplored processes that influence cognitive evaluations of a company's activities in a scenario where everyone is part of ‘the cause.’ The context of the pandemic, as an example of uncertain times, provides a unique opportunity to explore issue involvement or relevance (Ahn 2020; Choi 2020), as people were simultaneously involved in the cause and affected by it, thus offering a fruitful avenue to explore. As such, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Cognitive evaluations of a company’s CSR response are positively related to perceptions of CSR.

Perceived CSR and Supportive Behavior

It is broadly accepted that CSR positively influences behavior, such as satisfaction and trust with a company (Lombart and Louis 2014); identification with and commitment to a company (Su et al. 2017); and positive word of mouth (Markovic et al. 2022; Raza et al. 2020). When exploring individuals’ responses toward socially responsible companies, results from research appear rather conflicting. Some studies argue that individuals are more likely to support companies that adopt CSR strategies (Podnar and Golob 2007; Foster et al. 2009). Others, however, propose that the public may not care enough about a company’s CSR and thus there may not be a significant link between perceived CSR and support for a company (Carrigan and Attalla 2001; Vaaland et al. 2008). We challenge the latter view by exploring in depth the context of the pandemic, and whether the widely accepted relationship between perceived CSR and support for a company remains significant in uncertain times. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H4:

Perceptions of CSR are positively related to supportive intended behavior.

The extant literature hints at the mediating properties of perceived CSR in driving the public’s support for organizations, as a result of company’s CSR initiatives and communication about thereof (see Kim and Ferguson 2018; Ettinger et al. 2020). Building on Upadhye et al. (2019) and utilization theory (Olsen 1977), individuals may consider specific CSR activities as a cue that a company may ‘sustain in a long run,’ reducing potential risks and thus engendering support (e.g., purchase behavior) toward the company. For example, if an individual perceives the overall company’s CSR at a high level, it may lay a strong foundation to exhibit their support for the company. However, if the company fails to establish strong CSR, it will unlikely translate into supportive behavior (Nyilasy et al. 2014). Thus, perceived CSR becomes a required foundation for the abovementioned effects. Therefore, we can assume that perceived CSR is likely to act as at least a partial mediator that converts evaluations of specific CSR activities into the public’s support.

H5:

Perceptions of CSR at least partially mediate the relationships between (i) positive emotional evaluations; (ii) negative emotional evaluations; and (iii) cognitive evaluations and supportive intended behavior.

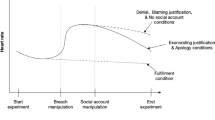

Figure 1 summarizes the mechanisms mentioned above, connecting the general public’s evaluations of a company’s response to the pandemic, perceived CSR, and supportive intended behaviors.

Methodology

Design and Sample

We tested the proposed conceptual model with data collected via an online survey in two countries representing Europe and Africa. The countries were selected for being among the most affected by the pandemic in their respective continent, during the first wave of the pandemic (JHU 2022). The research participants were invited to evaluate a supermarket’s overall approach to CSR and their response to the pandemic (in relation to responsible actions). The chosen supermarkets are compatible and were selected for the following reasons: both are among the largest supermarket chains in each country, and both follow the same business model and even share similar brand image. Each participant was directed to complete a survey about a supermarket from their country. The data collection was administered by Qualtrics, an online panel data provider, over the period between June 11 and July 9, 2020. The data were collected using a non-probability quota sampling strategy, including quotas of age and gender across both countries. Qualtrics ensured full completion of the survey; thus, no missing data were identified. The final sample accounted for 407 respondents.

Measures

The employed measures were derived from peer-reviewed research and based on the 5-point Likert scale. Perceived CSR was adapted from Fombrun et al. (2015) and formed out of three main RepTrak dimensions related to CSR (workplace environment, governance, and citizenship). Emotional evaluations (both positive and negative) of the supermarket’s response to the pandemic were adapted from PANAS by Watson et al. (1988). Cognitive evaluations were derived from Szőcs et al. (2016) and McCroskey (1966). The supportive intended behavior scale was based on previously operationalized measures related to support for an organization (Money et al. 2012; Hillenbrand et al. 2013). See Appendix Table 4 for an overview and Appendix Table 5 for key demographics.

Common Method Bias

To ensure that the collected data did not suffer from common method bias, the Lindell and Whitney (2001) statistical tests were performed. An additional variable—a marker—was added to the conceptual model (see Table 1). The results show that none of the correlations between the marker and the rest of the model constructs are exceeding the threshold of 0.300, suggesting that it is unlikely that the data set suffers from any common method bias.

Analysis

The model was tested using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling approach (PLS-SEM) (Sarstedt et al. 2022—see Raza et al. 2020) and operationalized through the SmartPLS 3.3 software (Ringle et al. 2015). PLS-SEM was deemed appropriate because of the nature of the study: (1) limited sample size; (2) occurrences of normal distribution parameters violation was identified when assessing z-skewness and z-kurtosis (Hair et al. 2019).

Following Hair et al.’s (2021) guidelines, the analysis involved two steps: Step 1 was focused on the evaluation of the measurement model, establishing reliability and validity (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha) (Cronbach 1951), composite reliability (Jöreskog 1971), consistent reliability (ρA) (Dijkstra and Henseler 2015), average variance extracted (AVE), and HTMT (Franke and Sarstedt 2019) assessment). Step 2 was aimed at evaluating the structural model, involving assessment of the paths within the tested model, evaluation of the coefficient of determination R2 and in-sample and out-of-sample (PLSpredict) predictive power estimation, in line with recent developments on the predictive power research (Shmueli et al. 2019).

Results

Measurement and Structural Model Assessments

The assessments of the constructs’ reliability (i.e., outer loading evaluations and reliability estimations) and validity (i.e., AVE and HTMT) were carried out—see Table 2. The overall results show acceptable levels of reliability and validity estimations for all endogenous and exogenous variables, confirming the measurement model (Hair et al. 2021).

To evaluate the significance of the proposed path relationships in the conceptual model, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples with percentile-based confidence intervals was run (Aguirre-Urreta and Rönkkö 2018). Table 3 shows all proposed path relationships and their significance levels at p < 0.05. Specifically, the model testing suggests that the coefficient of determination is moderate for both perceptions of CSR (R2 = 0.438) and intended behavior (R2 = 0.574).

In addition, we employed PLSpredict to establish out-of-sample predictive relevance. Using k = 10 folds and r = 1 repetitions (Shmueli et al. 2019), comparisons between PLS-SEM and LM (i.e., linear model regression) values were run (see Appendix Table 6). First, the analysis estimated whether the predictions within the model outperformed the most naïve benchmark (i.e., Q2predict > 0), which was confirmed. Next, root mean square error (RMSE) between PLS-SEM and LM values was compared. Following Schmueli et al. (2019), we used RMSE prediction statistics, due to the prediction error distributions for the outcome variables being symmetrical, which allows to ensure a balance between the model fit and the predictive power (Sharma et al. 2022). The results show high out-of-sample predictive power for all manifest variables.

The analysis of the structural model (Table 3) provides strong empirical evidence to the proposed hypotheses. As such, positive emotional evaluations and cognitive evaluations are both found to positively relate to perceived CSR; thus, H1 and H3 are, respectively, supported. Interestingly, we did not find empirical support for H2, as there is no significant effect of negative emotional evaluations on perceived CSR. Perceived CSR, in turn, is positively related to intended behavior, which provides support for H4.

Mediation Analysis

The analysis of mediation involved an estimation of direct, indirect, and total effects (Hair et al. 2021) shown in Table 3. The results suggest that perceptions of CSR partially mediate the relationships between (i) positive emotional evaluations and (ii) cognitive evaluations and intended behavior, while no mediation effect was identified for the path between negative emotional evaluations and intended behavior. These findings provide a partial support for H5.

Discussion

Our findings provide strong empirical evidence that both emotional and cognitive evaluations of CSR activities during uncertain times (i.e., response to a crisis) are significant drivers of perceptions of CSR and subsequent supportive behavior toward an organization. Specifically, we find that positive emotions have a significant effect on perceived CSR, while negative emotions do not have any effect, which is contrary to previous suggestions on the importance and impact of both positive and negative emotions (Dionne et al. 2018). This finding also contests previous research supporting the idea that negative emotions could decrease desired outcomes (Du and Fan 2007) and challenges the linear logic suggested by the ATE. In the context of this study, negative emotions do not affect supportive outcomes. This counter-intuitive finding could be explained in two ways. First, people might be willing to give the benefit of the doubt much more during challenging times. At times of uncertainty and/or crisis, people experience elevated levels of negative emotions, such as anger or sadness (Achabou 2020; Metzler et al. 2022), and the prevailing negative feelings could be suppressed by positive emotions toward CSR activities. People may believe “we are all in this together,” and even if they feel negatively toward the company’s actions aimed at relieving the effects of the adverse situation, they would still perceive the company’s general approach to CSR positively. Alternatively, people who experience negative emotions may find it difficult to demonstrate the support for a company and instead may be likely to withdraw their support in ways that were not captured in the applied measures, such as negative word of mouth, etc. (Barclay and Kiefer 2014).

Our study also finds cognitive evaluations as strong predictors of perceived CSR, supporting the results of previous research (Bhattacharya and Sen 2004; Wagner et al. 2008; Dastous and Legendre 2009). Despite the significant impact of positive emotional evaluations, they appear weaker in magnitude compared to cognitive evaluations. Our findings are particularly valuable as they not only signal a certain level of rationality in the public’s evaluations, but challenge previous research suggesting that cognitive evaluations of CSR activities are more relevant if individuals are not involved with the cause being supported (Choi 2020). Provided that the research participants were both involved and affected by the cause, we thus argue that in times of high-involvement uncertainty, people tend to rely more on their cognitive evaluations—mind—to make a judgment about a company, specifically its CSR. This finding advances the understanding of antecedents of perceived CSR (e.g., Stanaland et al. 2011), suggesting that cognitive evaluations are crucial for forming a perception of CSR.

The model testing also adds additional evidence on a positive influence of perceived CSR on support for an organization, which aligns with previous research in the field (Xie et al. 2019). Most interestingly, we identify a partially mediating role of perceived CSR, suggesting that (positive) emotional and cognitive evaluations influence the desired outcomes both directly and indirectly. This finding supports the work of Xie et al. (2019), among others, who suggest that positive emotions and cognitions drive behaviors.

Most notably, our results suggest that when supporting organizations, the public is driven more by their positive emotional evaluations, rather than cognitive evaluations. This is a significant finding, as in times of uncertainty, emotions seem dominant; thus, people express support to companies driven by heart. This finding extends the notion of how evaluations may impact intentions, suggesting that in situations of adversity, emotional evaluations may appear stronger predictors of intentions compared to cognitive evaluations (Doll and Ajzen 1992).

Overall, it seems that the public cares about companies’ responsible practices, even during uncertain times. Their mind would be driving their perceptions, but their heart will ultimately decide whether or not they will support that organization.

Theoretical Contributions

By exploring the relationships between the public’s evaluations of a company’s responses during a crisis, their perceptions of the company’s overall CSR, and the subsequent behavior toward the company, this study offers several contributions to the CSR literature. First, our paper expands prior knowledge by offering a more nuanced exploration of evaluations of CSR activities, considering both cognitive (mind) and emotional (heart) evaluations (Xie et al. 2019). This more comprehensive analysis highlights the importance of exploring emotional and cognitive evaluations individually, as suggested by van den Berg et al. (2006), in relation to different desired outcomes. As such, during challenging times, mind seems to be key in building positive perceptions of a company’s overall approach to CSR, while heart is the most important driver of supportive behavior (Keer et al. 2010).

Second, we contribute to research in the area of emotions and CSR by suggesting that negative emotions do not necessarily affect support for a company, as highlighted by previous research (e.g., Du and Fan 2007; Hillenbrand et al. 2020). In fact, during challenging times, people might be more willing to give the benefit of the doubt, perhaps, driven by a communal sentiment, and would still perceive the overall CSR efforts of the organization positively. This highlights the importance of the context in which the effects of negative emotions on outcomes are explored (Barclay and Kiefer 2014). As a result, this is a key contribution of our study, as it highlights the value of having a strong CSR strategy that would allow companies to positively engage with individuals even if those feel the company could have responded better to uncertain events.

Lastly, our study unpacks the (partially) mediating role of perceived CSR between evaluations of the company’s response during uncertain times and the supportive behaviors toward the company. This contributes to the body of knowledge on the role of perceived CSR (Lacey et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2021), suggesting that perceived CSR is vital when translating emotional and cognitive evaluations into supportive behavior.

Managerial Implications

Our study offers insights that companies could use not only during challenging times, but when engaging in CSR activities. First, managers are encouraged to consider both individuals’ emotions and cognitions when developing a specific CSR strategy/activity. Specifically, organizations should aim to be seen as behaving in right and honest ways, as this would directly impact how their CSR efforts are perceived. Furthermore, CSR activities should be able to evoke positive emotions, as they are vital in overall appraisal of CSR and even stronger when driving support from the public. As such, companies could focus on designing CSR initiatives which clearly link to a specific cause or purpose, and implement and communicate those in the most transparent manner. In doing so, they would relate to both cognitive and emotional aspects to gain their desired outcomes.

Second, the overall company’s CSR (i.e., the public’s perceptions of thereof) is fundamental to understand how the public will behave toward the organization. Hence, companies aiming to get the support of varied stakeholders should develop meaningful CSR strategies, which would balance the interest of different parties, particularly in challenging times.

Third, managers should be aware that their decisions are the corresponding result of affective and cognitive influences. In this regard, the CSR communication strategies that companies engage in need be carefully designed so that the public would understand what they are and be able to connect with them. Communication has a vital capacity to reach audiences and trigger specific responses; thus, perceptions about the CSR practices will depend on the manner in which they are communicated. Therefore, companies may choose to focus their CSR communication strategy on cognitive aspects if the goal is to improve (or sustain) a positive perception of their CSR. At the same time, if the company aims to raise the public’s support toward the company, it is prominent to build on affective arguments, which should trigger stronger emotional response as well as lead to more desired outcomes.

Finally, the study encourages managers to invest in their CSR that in fact can help them win over more benefits in the competitive market (provided that positively perceived CSR enables the company to secure supportive behavior from key stakeholders), regardless of the sudden changes (i.e., crisis) that can be happening in the external environment.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The paper has several limitations. First, data were collected during the first wave of the pandemic, using a cross-sectional approach. Future research could explore the public’s perceptions of CSR at the present time, aiming to understand if those perceptions have changed overtime. The current study does not take into consideration the time period of how long the effect of the CSR activity would last in the minds of the public to maintain positive cognitive or emotional evaluation. The duration of the effect needs to be examined in future research. It will be important to provide further insights into the degree of attention and awareness of CSR activities and its role in shaping perceptions of overall company’s CSR, and whether the absence of CSR initiatives could lead to negative cognitive and emotional evaluations.

Although we see the value of using supermarkets as a context (due to their essential role during the pandemic), other sectors and organization types could also be considered. While the supermarkets selected for this study were positively perceived by the public, future research could consider less regarded supermarkets to explore how their actions during uncertain times influence individuals’ perceptions and behaviors. Estimating the role of prior company’s reputation and motivation to engage in a particular CSR activity may shed additional light on how emotional and cognitive evaluations are formed.

This paper has focused on results from a global sample. Future studies could look more closely at country similarities/differences. Finally, this study calls for future research to explore the effects of CSR in different contexts rather than a public health crisis. It would be prudent to apply the developed framework to other challenging contexts (e.g., climate change, social injustice, economic collapse, etc.) and explore the dynamics of antecedents and consequences of perceived CSR.

References

Achabou, M.A. 2020. The effect of perceived CSR effort on consumer brand preference in the clothing and footwear sector. European Business Review 32 (2): 317–347.

Aguirre-Urreta, M.I., and M. Rönkkö. 2018. Statistical inference with PLSc using bootstrap confidence intervals. MIS Quarterly 42: 1001–1020.

Ahn, J. 2020. Understanding the role of perceived satisfaction with autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the CSR context. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28 (12): 2027–2043.

Almeida, M.D.G.M.C., and A.F.M. Coelho. 2019. The antecedents of corporate reputation and image and their impacts on employee commitment and performance: The moderating role of CSR. Corporate Reputation Review 22: 10–25.

Andreu, L., A.B. Casado-Díaz, and A.S. Mattila. 2015. Effects of message appeal and service type in CSR communication strategies. Journal of Business Research 68 (7): 1488–1495.

Anheuser-Busch. n.d. About our commitment to disaster relief and preparedness. https://www.anheuser-busch.com/community/disaster-relief. Accessed 10 January 2024.

Barclay, L.J., and T. Kiefer. 2014. Approach or avoid? Exploring overall justice and the differential effects of positive and negative emotions. Journal of Management 40 (7): 1857–1898.

BBC. 2020. Coronavirus: Sports Direct U-turns on opening after backlash. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-52011915. Accessed 7 August 2022.

Bhattacharya, C.B., and S. Sen. 2004. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review 47: 9–24.

Brown, T.J., and P.A. Dacin. 1997. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing 61 (1): 68–84.

Camerer, C., G. Lowenstein, and D. Prelec. 2005. Neuro-economics: How neuroscience can inform economics. Journal of Economic Literature 43: 9–64.

Carrigan, M., and A. Attalla. 2001. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behavior? Journal of Consumer Marketing 18: 560–577.

Chaudhuri, A., and M.B. Holbrook. 2001. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing 65: 81–93.

Chen, S., Y. Chen, and K. Jebran. 2021. Trust and corporate social responsibility: From expected utility and social normative perspective. Journal of Business Research 134: 518–530.

Choi, C.W. 2020. Increasing company-cause fit: The effects of a relational ad message and consumers’ cause involvement on attitude toward the CSR activity. International Journal of Advertising 41 (2): 333–353.

Cronbach, L.J. 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334.

D’Acunto, D., A. Tuan, D. Dalli, G. Viglia, and F. Okumus. 2020. Do consumers care about CSR in their online reviews? An empirical analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management 85: 102342.

Dastous, A., and A. Legendre. 2009. Understanding consumers’ ethical justifications: A scale for appraising consumers’ reasons for not behaving ethically. Journal of Business Ethics 87: 255–268.

Dawar, N., and P. Parker. 1994. Marketing universals: Consumers’ use of brand name, price, physical appearance, and retailer reputation as signals of product quality. Journal of Marketing 58 (2): 81–95.

Dijkstra, T.K., and J. Henseler. 2015. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly 39: 297–316.

Dionne, S.D., J. Gooty, F.J. Yammarino, and H. Sayama. 2018. Decision making in crisis: A multilevel model of the interplay between cognitions and emotions. Organizational Psychology Review 8 (2–3): 95–124.

Doll, J., and I. Ajzen. 1992. Accessibility and stability of predictors in the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63 (5): 754–765.

Dyllick, T., and K. Muff. 2016. Clarifying the meaning of sustainable business: Introducing a typology from business-as-usual to true business sustainability. Organization and Environment 29 (2): 156–174.

Ellsworth, P.C. 2013. Appraisal theory: Old and new questions. Emotion Review 5: 125–131.

Ettinger, A., Grabner-Kräuter, S., Okazaki, S. and R. Terlutter. 2021. The desirability of CSR communication versus greenhushing in the hospitality industry: The customers’ perspective. Journal of Travel Research 60(3): 618–638.

Fatma, M., I. Khan, V. Kumar, and A.K. Shrivastava. 2022. Corporate social responsibility and customer-citizenship behaviors: The role of customer–company identification. European Business Review 34 (6): 858–875.

Fombrun, C.J., L.J. Ponzi, and W. Newburry. 2015. Stakeholder tracking and analysis: The RepTrak® system for measuring corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 18 (1): 3–24.

Foster, M., A. Meinhard, I. Berger, and P. Krpan. 2009. Corporate philanthropy in the Canadian context: From damage control to improving society. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38: 441–466.

Franke, G., and M. Sarstedt. 2019. Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: A comparison of four procedures. Internet Research 29: 430–447.

Garcia-De los Salmones, M., and A. Perez. 2018. Effectiveness of CSR advertising: The role of reputation, consumer attributions, and emotions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25 (2): 194–208.

Hair, J.F., Jr., G.T.M. Hult, C.M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2021. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). London: Sage.

Hair, J.F., M. Sarstedt, and C.M. Ringle. 2019. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing 53: 566–584.

He, H., and L. Harris. 2020. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. Journal of Business Research 116: 176–182.

Hillenbrand, C., K. Money, and A. Ghobadian. 2013. Unpacking the mechanism by which corporate responsibility impacts stakeholder relationships. British Journal of Management 24 (1): 127–146.

Hillenbrand, C., A. Saraeva, K. Money, and C. Brooks. 2020. To invest or not to invest?: The roles of product information, attitudes towards finance and life variables in retail investor propensity to engage with financial products. British Journal of Management 31: 688–708.

Hofenk, D., M. van Birgelen, J. Bloemer, and J. Semeijn. 2019. How and when retailers’ sustainability efforts translate into positive consumer responses: The interplay between personal and social factors. Journal of Business Ethics 156 (2): 473–492.

Hosany, S., G. Prayag, R. Van Der Veen, S. Huang, and S. Deesilatham. 2017. Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research 56 (8): 1079–1093.

Johns Hopkins University and Medicine (JHU). 2022. Coronavirus Resource Centre. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data. Accessed 7 September 2022.

Jones, D. A. 2019. The psychology of CSR. Section "Introduction" (Micro/HR Issues), Chapter 1. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological and Organizational Perspectives, eds. A. McWilliams, D.E. Rupp, D.S. Siegel, G. Stahl and D.A. Waldman. Oxford University Press.

Joireman, J., D. Smith, R.L. Liu, and J. Arthurs. 2015. It’s all good: Corporate social responsibility reduces negative and promotes positive responses to service failures among value-aligned customers. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 34 (1): 32–49.

Jöreskog, K.G. 1971. Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika 36: 409–426.

Keer, M., M. Conner, B. Van den Putte, and P. Neijens. 2014. The temporal stability and predictive validity of affect-based and cognition-based intentions. British Journal of Social Psychology 53 (2): 315–327.

Keer, M., B. Van den Putte, and P. Neijens. 2010. The role of affect and cognition in health decision making. British Journal of Social Psychology 49: 143–153.

Kim, H.S., and S.Y. Lee. 2015. Testing the buffering and boomerang effects of CSR practices on consumers’ perception of a corporation during a crisis. Corporate Reputation Review 18: 277–293.

Kim, S.M., and J. Bae. 2016. Cross-cultural differences in concrete and abstract corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaigns: Perceived message clarity and perceived CSR as mediators. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 1 (1): 1–14.

Kim, S., and M.A.T. Ferguson. 2018. Dimensions of effective CSR communication based on public expectations. Journal of Marketing Communications 24 (6): 549–567.

Kim, S., and H. Lee. 2020. The effect of CSR fit and CSR authenticity on the brand attitude. Sustainability 12 (1): 275.

Lacey, R., A.G. Close, and R.Z. Finney. 2010. The pivotal roles of product knowledge and corporate social responsibility in event sponsorship effectiveness. Journal of Business Research 63 (11): 1222–1228.

Lange, D., P.M. Lee, and Y. Dai. 2011. Organizational reputation: A review. Journal of Management 37 (1): 153–185.

Lazarus, R.S. 1991. Emotion and Adaptation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lee, E.M., S.Y. Park, and H.J. Lee. 2013. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business Research 66 (10): 1716–1724.

Lindell, M.K., and D.J. Whitney. 2001. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (1): 114–121.

Liu, Y., S. Liu, Q. Zhang, and L. Hu. 2021. Does perceived corporate social responsibility motivate hotel employees to voice? The role of felt obligation and positive emotions. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 48: 182–190.

Lombart, C., and D. Louis. 2014. A study of the impact of Corporate Social Responsibility and price image on retailer personality and consumers’ reactions (satisfaction, trust and loyalty to the retailer). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21 (4): 630–642.

Lu, L.C., W.P. Chang, and H.H. Chang. 2014. Consumer attitudes toward blogger’s sponsored recommendations and purchase intention: The effect of sponsorship type, product type, and brand awareness. Computers in Human Behaviour 34: 258–266.

Luo, X., and C.B. Bhattacharya. 2006. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing 70 (4): 1–18.

MacKenzie, S.B., and R. Lutz. 1989. An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing 53 (2): 48–65.

Mahmud, A., D. Ding, and M.M. Hasan. 2021. Corporate social responsibility: Business responses to Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic. SAGE Open 11 (1): 1–17.

Maon, F., J. Vanhamme, K. De Roeck, A. Lindgreen, and V. Swaen. 2019. The dark side of stakeholder reactions to corporate social responsibility: Tensions and micro-level undesirable outcomes. International Journal of Management Reviews 21 (2): 209–230.

Markovic, S., O. Iglesias, Y. Qiu, and M. Bagherzadeh. 2022. The CSR imperative: How CSR influences word-of-mouth considering the roles of authenticity and alternative attractiveness. Business & Society 61 (7): 1773–1803.

McCroskey, J.C. 1966. Scales for the Measurement of Ethos. Speech Monographs 33: 65–72.

Metzler, H., B. Rimé, M. Pellert, T. Niederkrotenthaler, A. Di Natale, and D. Garcia. 2022. Collective emotions during the COVID-19 outbreak. Emotion 23 (3): 844.

Money, K., C. Hillenbrand, I. Hunter, and A.G. Money. 2012. Modelling bi-directional research: A fresh approach to stakeholder theory. Journal of Strategy and Management 5 (1): 5–24.

Moors, A. 2014. Flavors of appraisal theories of emotion. Emotion Review 6 (4): 303–307.

Moscato, D., and T. Hopp. 2019. Natural born cynics? The role of personality characteristics in consumer skepticism of corporate social responsibility behaviors. Corporate Reputation Review 22: 26–37.

New York Times. 2020. Strikes at Instacart and Amazon Over Coronavirus Health Concerns. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/business/economy/coronavirus-instacart-amazon.html. Accessed 7 August 2022.

Newell, B.R., D.A. Lagnado, and D.R. Shanks. 2007. Straight Choices: The Psychology of Decision Making. New York: Psychology Press.

Nyilasy, G., H. Gangadharbatla, and A. Paladino. 2014. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. Journal of Business Ethics 125 (4): 693–707.

Ooi, S.K., J.A. Yeap, and Z. Low. 2022. Loyalty towards telco service providers: The fundamental role of consumer brand engagement. European Business Review 34 (1): 85–102.

Podnar, K., and U. Golob. 2007. CSR expectations: The focus of corporate marketing. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 12: 326–340.

Raza, A., Rather, R.A., Iqbal, M.K. and U.S. Bhutta. 2020. An assessment of corporate social responsibility on customer company identification and loyalty in banking industry: a PLS-SEM analysis. Management Research Review 43(11): 1337–1370.

RepTrak. 2020. Doing and Saying the Right Thing During a Crisis: How Businesses Have Responded to Covid-19. https://www.reptrak.com/blog/ng-saying-right-thing-during-crisis-how-businesses-responded-covid19/. Accessed 27 March 2020.

Ringle, C.M., S. Wende, and J.M. Becker. 2015. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH.

Roseman, I.J. 2013. Appraisal in the emotion system: Coherence in strategies for coping. Emotion Review 5: 141–149.

Roseman, I.J., and C.A. Smith. 2001. Appraisal theory: Overview, assumptions, varieties, controversies. In Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research, ed. K.R. Scherer, et al., 3–19. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sarstedt, M., Hair Jr, J. F., and Ringle, C. M. 2022. ‘PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet’–retrospective observations and recent advances. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 1–15.

Scherer, K.R. 2009. The dynamic architecture of emotion: Evidence for the component process model. Cognition and Emotion 23: 1307–1351.

Schons, L., and M. Steinmeier. 2016. Walk the talk? How symbolic and substantive CSR actions affect firm performance depending on stakeholder proximity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 23 (6): 358–372.

Sen, S., and C.B. Bhattacharya. 2001. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2): 225–243.

Sen, S., C.B. Bhattacharya, and D. Korschun. 2006. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (2): 158–166.

Sharma, P.N., B.D.D. Liengaard, J.F. Hair, M. Sarstedt, and C.M. Ringle. 2022. Predictive model assessment and selection in composite-based modeling using PLS-SEM: Extensions and guidelines for using CVPAT. European Journal of Marketing 57 (6): 1662–1667.

Shin, H., Sharma, A., Nicolau, J. L. and J. Kang. 2021. The impact of hotel CSR for strategic philanthropy on booking behavior and hotel performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Management 85: 104322.

Shmueli, G., M. Sarstedt, J.F. Hair, J.H. Cheah, H. Ting, S. Vaithilingam, and C.M. Ringle. 2019. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing 53: 2322–2347.

Stanaland, A.J., M.O. Lwin, and P.E. Murphy. 2011. Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 102: 47–55.

Su, L., Y. Pan, and X. Chen. 2017. Corporate social responsibility: Findings from the Chinese hospitality industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 34: 240–247.

Sung, B., S. La Macchia, and M. Stankovic. 2023. Agency appraisal of emotions and brand trust. European Journal of Marketing 57 (9): 2486–2512.

Szőcs, I., B.B. Schlegelmilch, T. Rusch, and H.M. Shamma. 2016. Linking cause assessment, corporate philanthropy, and corporate reputation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 44 (3): 376–396.

Teilegen, A. 2019. Structures of mood and personality and their relevance to assessing anxiety, with an emphasis on self-report. In Anxiety and the anxiety disorders, pp. 681–706. Routledge.

Tetrault Sirsly, C., and E. Lvina. 2019. From doing good to looking even better: The dynamics of CSR and reputation. Business and Society 58 (6): 1234–1266.

The Washington Post. 2020. Walmart employees say they’re preparing for job cuts as retailer rolls out its ‘Great Workplace’ program. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/business/50-biggest-companies-coronaviruslayoffs/ Accessed 17 June 2024.

Upadhye, B.D., G. Das, and G. Varshneya. 2019. Corporate social responsibility: A boon or bane for innovative firms? Journal of Strategic Marketing 27 (1): 50–66.

Vaaland, T., M. Heide, and K. Grønhaug. 2008. Corporate social responsibility: Investigating theory and research in the marketing context. European Journal of Marketing 42: 27–953.

Van den Berg, H., A.S. Manstead, J. van der Pligt, and D.H. Wigboldus. 2006. The impact of affective and cognitive focus on attitude formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (3): 373–379.

Ventilator Challenge UK. 2020. VentilatorChallengeUK Consortium. https://www.ventilatorchallengeuk.com/. Accessed 7 May 2020.

Visser, S.W.J., and C.B. Scheepers. 2022. Organisational justice mechanisms’ mediating leadership style, cognition-and affect-based trust during COVID-19 in South Africa. European Business Review 34 (6): 776–797.

Vlachos, P.A., A. Krepapa, N.G. Panagopoulos, and A. Tsamakos. 2013. Curvilinear effects of corporate social responsibility and benevolence on loyalty. Corporate Reputation Review 16: 248–262.

Wagner, T., P. Bicen, and Z. Hall. 2008. The dark side of retailing: Towards a scale of corporate social irresponsibility. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 36: 124–142.

Walsh, G., S.E. Beatty, and E. Shiu. 2009. The Customer-based Corporate Reputation Scale: Replication and Short Form. Journal of Business Research 62 (10): 924–930.

Walsh, G., E. Shiu, L.M. Hassan, N. Michaelidou, and S.E. Beatty. 2011. Emotions, store-environmental cues, store-choice criteria, and marketing outcomes. Journal of Business Research 64 (7): 737–744.

Watson, D., L.A. Clark, and A. Tellegen. 1988. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (6): 1063–1070.

Xie, C., R.P. Bagozzi, and K. Grønhaug. 2019. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer brand advocacy: The role of moral emotions, attitudes, and individual differences. Journal of Business Research 95: 514–530.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saraeva, A., Garnelo-Gomez, I. & Shamma, H. "Mind over heart?": Exploring the influence of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to CSR in challenging times. Corp Reputation Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-024-00196-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-024-00196-0