Abstract

A collective regional identity is a favourable condition for the acceptance of majority decisions made at the regional level and for the delegation of competencies from the central to regional governments. Moreover, a regional identity can play an important role in times of global challenges. Regional attachment might generate a we-feeling and help individuals to cope better with a complex world. The same feeling, however, might also serve as a basis for exclusionary attitudes. In this article, we analyse regional identity at the Land level in Germany with data from the German General Social Survey. Our results show that regional identity is strong in both the eastern and western parts of the country, with people in the east, surprisingly, identifying with their respective Land slightly more than people in the west, even though the five eastern Länder were only established in 1990 after decades of centralist rule. Furthermore, the dark side of regional identity manifests itself only in eastern Germany, where a stronger regional identity tends to go hand in hand with a greater dislike of foreigners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The political importance of regions as sub-national entities is not only reflected in the degree of political autonomy they enjoy or the scope of their legislative powers, but also in the extent to which people feel attached to their region. There are several reasons justifying an in-depth study of regional identity: Shared feelings of regional identity represent a favourable condition for the delegation of competencies from the national to the regional level and for the population to accept majority decisions made by regional governments, particularly with regard to redistributive policies. A collective identity is thus fundamental to democratic government in sub-national entities. With regard to Germany, the question arises to what extent east Germans identify with the Länder founded in the course of reunification. Does this identification become stronger over time as east Germans grow more accustomed to their respective Land? Are there systematic differences between younger cohorts who spent their formative years in the re-established Länder and older cohorts? A sense of unity and solidarity in the Länder can also serve as a basis of legitimacy for further decentralization. This is of political importance as Germany is still discussing decentralization and recentralization options ranging from education policy to the reform of the interstate fiscal equalization system.

A further reason is the important role that a regional identity can play in times of accelerating globalisation. Faced with the erosion of national sovereignty, increased immigration, growing social inequality, and rapid cultural change, many people feel uneasy and disoriented. Local and regional attachment can provide answers in the search for points of orientation and roots and thus help individuals to cope with an increasingly complex world. A strong regional identity might also have a dark side, however, in the sense that it provides a breeding ground for exclusionary attitudes. Drawing on social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1986), we ask whether people who identify with narrowly defined communities (such as the Land, or the former Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) or the German Democratic Republic (GDR)) tend to perceive themselves as a distinct group with a shared experience and as a consequence disapprove of out-groups, such as foreigners, more strongly than other respondents. Our analysis of exclusionary tendencies rooted in regional identity thus focuses on the connection between this identity and the dislike of foreigners. Unfortunately, this question is relevant for Germany as well: In some parts of the population, xenophobia has long been a sad reality, and the wide differences in people’s attitudes towards migration that has been observed in recent years illustrate how topical the issue is. These differences in attitudes are also relevant for the acceptance and support of migration policies, in which the Länder have a significant say. They have independent legislative powers in culture and education as well as considerable leeway in how they implement federal laws—a fact that is often overlooked. Research has shown that the Länder use their competences to pursue policies that clearly differ from each other, e.g. with regard to the naturalisation of foreigners, the recognition of foreign educational qualifications (Münch 2016) or the question of whether civil servants are allowed to wear a headscarf (Blumenthal 2009). The integration of foreigners is directly linked to questions of identity, as are aspirations for regional distinctiveness and autonomy. A growing body of literature therefore investigates the question whether integration policy in multi-level states varies according to the strength of regional identity (for an overview see Adam and Hepburn 2019). Our study on regional identity and dislike of foreigners aims to contribute to this discussion.

Our analyses employing data from the German General Social Survey (ALLBUS) show that east Germans generally identify strongly—and to a slightly greater extent than west Germans—with their Land. A relationship between regional identity and exclusionary attitudes towards foreigners is only evident in eastern Germany, where a stronger identification with the former GDR and with the respondents’ Länder tends to correspond to greater disapproval of foreigners.

Theoretical considerations on social comparisons, out-group perceptions, and regional identity

People need to feel they belong to a social group, sharing its collective identity, and to distinguish themselves from others in order to perceive themselves as individuals and thus to be able to develop a self-identity in the first place. Such social categorization (in-/out-group distinction) is used by individuals to define their social environment and their place within it. It facilitates the predictability of human actions and thus social coexistence (see Hogg 2010). The social identity theory developed by Tajfel and Turner in the 1970s is based on these considerations (see inter alia Tajfel 1974). Social identity consists “of those aspects of an individual’s self-image that derive from social categories to which he perceives himself as belonging” (Tajfel and Turner 1986, p. 16).

According to Tajfel and Turner, the social categorization of other people is very important for the self. People tend to categorize others on the basis of perceived similarities and differences they share with them, identifying themselves and others as members of the same category (in-group member) or different categories (out-group member) (Hogg 2010; Huddy 2001). In such social comparisons between oneself as an in-group member and others as out-group members (or between the in-group and the out-group in general) there is a tendency to focus on the similarities within the own group and on the differences between this and other groups, thus maximizing distinctiveness between groups (cf. Hogg and Abrahams 1988, p. 22ff.). As individuals strive for a positive social identity or positive self-esteem, they tend to evaluate their own group positively and to devalue the out-group in such comparisons,Footnote 1 tipping the scales in their favour. These processes associated with social identities are also important for understanding the effects of identification with different political units.

For national identity this has already been demonstrated. For instance, Blank and Schmidt (2003) show that nationalism as a dimension of national identity characterised, for example, by a feeling of national superiority, is related to dislike of foreigners. This association has been confirmed by several studies focusing on Germany (e.g. Schmidt and Heyder 2000; Wagner et al. 2012) and other countries (e.g. Huddy and Del Ponte 2019). One conclusion that can be drawn from these studies on national identities and exclusionary attitudes is that political identities can have both inclusionary and exclusionary effects. However, this research also shows that different forms of political identity can differ in their effects on political attitudes (e.g. Esses et al. 2005).

Given these findings it is surprising that the question whether there is a connection between exclusionary attitudes towards foreigners or immigrants and identification with sub-national levels, which we examine in this paper, is less well-researched (for an exception see Curtis 2014; Hooghe and Stiers 2020). The regional level is an important element of the multi-level character of political identities. Individuals can have multiple identities and people in Europe might not only feel attached to the national and/or European level, but also to the region they live in (Nicoli et al. 2020).

In many parts of Europe, regions and the political, economic, and cultural roles they play have been receiving growing attention in recent decades (Antonsich 2010, p. 262–263). One reason is the relative decline in the importance of nation states as the world becomes more and more connected and, above all, economically globalised: “Nation states are regarded as too small for global economic competition … while being too large and remote for cultural identification and participatory and active citizenship” (Paasi 2009, p. 123).

With regard to social identities, researchers are discussing the consequences of these multiple processes of internationalization for national identities (e.g. Ariely 2012), but the possibility of a rising significance of regional identities should be considered as well, because in a world in which borders are becoming increasingly fluid there is a growing need for points of orientation and roots (Meyer and Geschiere 1999). Sub-national units, such as regions, can satisfy this need and help individuals to cope with an ever and more complex world. As some studies show, regional identities can influence various political attitudes. One example are the connections between regional identities and favourable opinions on decentralization (e.g. Verhaegen et al. in this issue; Medeiros and Gauvin in this issue) or even regional independence. Studies on Spain show how complex these connections can be (e.g. Serrano 2013; Guinjoan and Rodon 2014). There is also evidence of effects that regional identities have on political behaviour (e.g. Jeffery and Hough 2009; Chernyha and Burg 2012) and on ideological positions (Galais and Serrano 2020).

A strong regional identity might also serve as a basis for exclusionary attitudes. First, this is a probable scenario, assuming that the findings on the links between a certain dimension of national identity and out-group derogation can be transferred to the sub-national level. Second, the theoretical considerations on the two human needs of belongingness (by emphasizing similarities within the own group) and uniqueness and individuation (by distinguishing oneself from other groups) discussed above can be transferred to identification with smaller communities. According to Brewer (1991), individuals differ in the extent to which they feel these needs. While for some people the need for inclusion outweighs the need for distinctiveness, which allows them to identify with broad, all-encompassing social groups such as Europe and the Europeans, for others the opposite applies: They draw sharper boundaries around their groups and tend to identify with more narrowly defined communities, such as their region (see Brigevich 2018, p. 642). Due to their greater need for differentiation, the latter are more likely to engage in out-group derogation and hold exclusionary beliefs than the former.

Expectations regarding trends and correlates of regional identity in Germany

On the basis of xenophobia in Germany we analyse whether people who identify with narrowly defined communities actually do devalue out-groups and their members and if yes, to what extent. Apart from the Land, decades of separation have created two other objects of identification at the sub-national level: the former GDR and the former FRG.

As previously mentioned, existing research on the relationships between sub-national identities and out-group devaluation is very limited. In the only international comparative study known to us, Curtis (2014) finds no effect of regional identity on the disapproval of immigration. By asking respondents to rate the extent to which they “feel regional,” Curtis uses a more general measurement of collective identity, however, which does not capture differentiation from other groups to the same extent as nationalism, for example. Studies on the relationship between a strong regional identity and negative attitudes towards European integration (which could indicate a strong desire for clear lines of demarcation between “us” and “them”) create a contradictory picture (Brigevich 2018; Chacha 2013). A recent study from Belgium finds a strong relationship between a regional, Flemish identity and a restrictive attitude towards immigrants, and points to the role of specific characteristics of a country’s different territorial units that are linked to the identities people developed there (Hooghe and Stiers 2020).

In his study on regional identity in the eastern German Land of Saxony, Mäs (2005) argues that the effect of regional identity on the dislike of foreigners depends on contextual conditions, which he justifies with reference to the concept of poor white racism (Hogg and Abrams 1988; Hogg and Vaughan 2018). According to this concept, members of a group who feel disadvantaged relative to other groups (such as white blue-collar workers in the USA) tend to express a particularly high degree of dislike towards out-groups in order to improve their self-image.

Mäs (2005) draws on this argument in his comparison of eastern and western Germany. He argues and shows empirically that a stronger regional identity corresponds to a greater dislike of foreigners, particularly when the respondents perceive themselves as second-class citizens relative to west Germans. Which expectations for our analysis can we derive from this research? The positive relationship between a strong sub-national identity and a dislike of foreigners should be more evident in eastern Germany than in western Germany. Identification with the former GDR is expected to have a stronger effect: As an object of identification from the era of the East–West-German division it stands for a clear desire to distinguish oneself from western Germany.Footnote 2

Irrespective of the effect on the dislike of foreigners, there might be differences between the two parts of the country with regard to identification with the Land: In 1945 all four Allied Powers sub-divided their occupation zones into Länder.Footnote 3 In 1952, however, the GDR dissolved the newly founded five Länder on its territory and replaced them with fourteen districts, thus ensuring the party’s control of the state apparatus on the regional level. In the revolutionary autumn of 1989, calls for the Länder to be re-established were made early on, particularly in Saxony, where the traditional white-green state flags were part of the Monday demonstrations in Dresden from the very beginning (Laufer and Münch 1998). The question of the exact borders of these Länder remained open until July 1990, when, after careful discussion of alternative solutions, the Volkskammer—the East German parliament democratically elected in March 1990—decided to re-establish the Länder that had been dissolved in 1952. Since the east German Länder had not existed for almost forty years, identification with the Land might be expected to be less strong in the eastern than in the western part of the country.

The widely documented calls for re-federalization made during the democratic revolution suggest otherwise, however. They were spurred by critical analysis of and conscious dissociation from the GDR’s centralism (Laufer and Münch 1998). More important than the GDR, which ceased to exist three decades ago, are the experiences of east Germans in reunited Germany. After 1990, the regional political arena offered east Germans the opportunity to articulate criticism of the reunification process—a transformation that was often perceived as overpowering. In particular, the regional level might have represented an important point of orientation for east Germans in their search for identity at a time when the old regime had collapsed, their expectations of the new regime were disappointed, and when they felt only limited attachment to the political community of Germany as a whole (Neller 2006, p. 100).

While we cannot formulate clear expectations for the degree of identification with the Land in eastern Germany, we can do so for changes in this identification. We expect it to increase over time, as east Germans feel more and more at home in their re-established Länder. In addition, we expect east German respondents who spent their formative years in the re-established Länder after 1990 to identify more strongly with their Land than older cohorts because regional identity, like other fundamental value orientations, is shaped by primary and early secondary socialization (Mühler and Opp 2007).

Constructs and indicators

We test our hypothesis with data from the German General Social Survey (ALLBUS), a large scale survey that has been regularly conducted since 1980 on attitudes and behaviour in Germany. The ALLBUS surveys conducted in 1991, 2000, 2008 and 2016 contain a battery of questions asking how attached respondents feel to various political units, including the Land and the former part of the country (i.e. FRG or GDR) with scale values running from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very strongly”). We use these four surveys to map the changes in regional identity in east and west Germany over time. Our selection of this indicator follows a recommendation by Sinnott (2005, p. 222).

For the analysis of a potential connection between regional identity and dislike of foreigners we rely on the most recent of the four surveys, ALLBUS 2016, which interviewed 3,490 respondents from a sample of adult persons living in private households (CAPI—Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing). The interviews were conducted between April and September 2016.

We measure dislike of foreigners with an additive index, which was created from the following three items (one factor 65.3% variance explained, Cronbach’s alpha 0.73): “When jobs get scarce, foreigners living in Germany should be sent home again,” “Foreigners living in Germany should be prohibited from taking part in any kind of political activity in Germany,” and “Foreigners living in Germany should choose to marry people of their own nationality” (scale values run from 1 “completely disagree” to 7 “completely agree”). This index represents a broad and proven measure for dislike of foreigners, as it comprises different dimensions of exclusionary attitudes (e.g. Semyonov et al. 2004).

If we want to adequately model the relationships between sub-national identities and attitudes towards foreigners, we need to consider other factors that may be related to both. First, we control for contacts with foreigners. According to the intergroup contact theory, contacts of individuals with members of an out-group lead to a more favourable view of this group (Pettigrew 1998). Numerous studies show that contacts with foreigners correspond to more positive attitudes towards this population group in Germany (e.g. Schmidt and Weick 2017). At the same time, contact with foreigners could also reduce feelings of belonging to sub-national communities. We create an additive index from four variables that measure whether respondents have personal contacts with foreigners in their families, at work, in their neighbourhood, or in their circle of friends and acquaintances (e.g. Bohrer et al. 2019).

Second, we control for possible influences of authoritarianism and right-wing ideology. Authoritarianism can be understood as an attitudinal syndrome, a tendency to submit to authorities, to endorse existing norms, and to dislike groups that seem to deviate from these norms (e.g. Altemeyer 1988). It relates to negative views of foreigners, as people with authoritarian attitudes tend to dislike social minorities, such as foreigners, who they perceive as violating in-group homogeneity (Thomsen et al. 2008, p. 1455). Our measure of authoritarian attitudes consists of an additive index created from two items: authoritarian submission (“we should be grateful for leaders who can tell us exactly what to do and how to do it”) and conventionalism (a child should be “forced to conform to his or her parents’ ideas”). We know from previous studies that right-wing political orientations can also involve negative attitudes towards foreigners (e.g. Raijman et al. 2003). Moreover, for adherents of right-wing ideology, not only national but sub-national identities might be relevant as well. Right-wing ideological orientations are measured by an individual’s self-placement in the left–right continuum.

Third, we build on the results of previous studies (e.g. Kuntz et al. 2017) and control for evaluations of the country’s economic situation in our model. Perceived economic insecurity might increase negative attitudes towards foreigners (who are seen as rivals in the labour market). Economic insecurity in the country could strengthen an individual’s attachment to sub-national units as a source of reassurance. Finally, we use education and age as control variables. According to previous studies (e.g. Rajiman et al. 2003), dislike of foreigners tends to decrease with education and to increase with age (see Table A-1 in Online Appendix for descriptive information on all variables).

Results

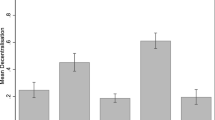

We present our findings in two steps. First, we describe the development of regional identity in Germany. Our analysis focuses on the respondents’ identification with their Land. With our findings we can contribute to the international discussion of questions of regional identity. We also address a German peculiarity by investigating attachment to the former part of the country (FRG/GDR). Second, we explain our results concerning the relationships between regional identity and dislike of foreigners. While conflicting arguments did not allow us to present hypotheses about the extent to which people in east Germany identify with their Land, we formulated clear expectations about changes in their identification in our theoretical discussion. As outlined above, attachment to the Land is expected to increase over time as east Germans become more and more accustomed to the re-established Länder. Figure 1 presents the results of a test of this hypothesis using data from the four waves of the ALLBUS that contain the question of attachment to the Land (1991, 2000, 2008, and 2016, standard deviations are displayed in Table A-2 in Online Appendix). They show that identification with the Land has increased steadily in eastern Germany. The same tendency can be observed for western Germany, but it is less pronounced there. As soon as one year after reunification, east Germans identified not less but actually slightly more with their respective Land than west Germans. This could indicate that east Germans readily accepted the re-established Länder. They might have been perceived as particular points of orientation or as distinct political units, different from Germany as a whole, in which they could express criticism of the reunification process. In the following three periods, east Germans felt more strongly attached to their Land than west Germans as well.Footnote 4 Thus, the short historical tradition of the east German Länder as sub-national political entities is not reflected in a low level of regional identity.

As regional identity is shaped by socialization, we expect regional identification to be stronger among east German respondents who spent their formative years in the re-established Länder. Figure 2 shows a comparison of this young cohort (born in 1975 or later) with a middle cohort (born between 1950 and 1974) and an older cohort (born up to and including 1949). Our definition of these three cohorts is guided by Svallfors’ (2010) seminal study on the development of attitudes towards government responsibilities in Germany. He describes the cohorts as follows: “Those who were already fully established in adult life at reunification (that is, born before 1950) will be compared to a middle cohort (born between 1950 and 1974), and to one consisting of those who were still children at reunification (that is, born after 1975)” (Svallfors 2010, p. 128). Due to their age, members of the young cohort did not participate in the survey of 1991. The results contradict our expectations: The respondents from the young cohort identify least with their Land, whereas the middle and especially the older cohort show a significantly higher degree of identification (for standard deviations see Table A-3). In general, older respondents can be expected to have a stronger collective regional identity as the development of collective identities takes time. Thus bonds should strengthen as people age. In this case, however, this argument does not apply because the identification object Land did not exist in eastern Germany before 1990. In other words, the older respondents did not have more time than the younger ones to form an attachment to the Länder; they were only older when the Länder were re-established. This finding might be attributed to the fact that older respondents have a greater willingness to form emotional attachments to collectives or a greater need for such bonds. However, this is only speculation and requires further research.

We use Fig. 3 to analyse the changes in attachment to the former part of the country over time (for standard deviations see Table A-4). The considerably weaker identification of east German respondents in 1991 could reflect their dissociation from the former regime, which they had only recently officially declared by reuniting with west Germany. In later years, the values are higher, which may be explained by the negative experiences east Germany made in unified Germany during the transformation period, causing them to turn to the former political community of the GDR (Grix 2000; Dalton and Weldon 2010).

From 2000 onwards, attachment to the former part of the country no longer differs significantly between east and west Germany. After 2000, east Germans’ attachment is slowly declining, while in west Germany this process is evident already after 1991: The longer the period since reunification, the lower the attachment to the FRG or the GDR, respectively, as the political communities of the former GDR and FRG as objects of orientation cease to exist or memories of them fade (Neller 2005: p. 353). A comparison of the two measures of regional identity shows that since 2008 people’s attachment to the Land has been significantly higher in east and west Germany than their attachment to the FRG or the GDR.

We now turn to the association between regional identity and dislike of foreigners. For the purpose of clarity, we will initially conduct the analyses separately for east and west Germany before testing a joint model for Germany as a whole with interaction terms between the part of the country (east/west) and our two measures of regional identity. Apart from the control variables, Fig. 4 contains the variable Attachment to the Land and Fig. 5 the variable Attachment to former part of the country. Coefficients and their standard errors are displayed in Tables A-5 and A-6 in Online Appendix. To facilitate comparison of the effects of the individual predictors, all predictors were recoded to a property range between 0 and 1.

As theoretically postulated, dislike of foreigners rises with increasing identification with the Land in east Germany, but not in west Germany. For respondents in east Germany who feel very strongly attached to their Land (scale value = 1) the value on the dislike-of-foreigners scale, which ranges from 1 to 7, is 0.46 points greater than the value for respondents in east Germany who feel not attached to their Land at all (scale value = 0). For Attachment to former part of the country (in this case: GDR), the difference is even somewhat greater (0.493 points). This confirms that regional identity in the new Länder has an exclusion component.

Some control variables show significantly stronger effects: Respondents in eastern Germany with extreme right views, for example, rank 1.556 points higher on xenophobia than respondents with extreme left views, and east German respondents who consider the economic situation in Germany to be very good score 1.659 points lower on xenophobia than respondents who consider it to be very bad (see Table A-6). These strong effects are not surprising since they are established predictors from research on xenophobia. We therefore consider this to confirm our hypothesis that our two measures of regional identity in east Germany can still have a significant influence after controlling for predictors that produce such strong effects. The effects of the other control variables are consistent with the findings of previous studies: The more authoritarian and the older a respondent is, the more strongly he or she dislikes foreigners (although the age effect is only significant in west Germany). Conversely, dislike of foreigners decreases with wider contacts and higher education.

As an additional test we run a full model including respondents from east and west Germany with interaction effects between both measures of regional identity (Land; former parts of the country) and an east Germany dummy (see Table 1).Footnote 5 Both interaction effects are significant (see models 2 and 4 in Table 1), once more confirming that the association between regional identity and dislike of foreigners holds in east Germany but not in west Germany. Figures A-1 and A-2 in Online Appendix present the marginal effect of being surveyed in east Germany for all levels of both regional identity scales. For the purpose of clarity, the original variables (scale values running from 1 to 4) were used. BinsFootnote 6 estimated according to Hainmueller et al. (2019) show that the linear interpretation of both interactions is valid.

Concluding remarks

Despite a rise in recent decades, the number of empirical studies dealing with the political importance of regions and regional communities is still limited. With regard to people’s relationships with their regional communities, our analysis of regional identity in Germany makes an important contribution to this field of research. First, our results show a strong sense of attachment to the respective Land in eastern Germany and a very pronounced increase in regional identity over time in this part of the country. These findings indicate that identification with political structures is possible even if they are of relatively recent origin and that attachment to the sub-national level after a system transformation can actually fill a social-identity vacuum. Our analysis thus not only complements the research on trends of political support among Germans at the national level, but also studies on the relationship between changes in state structures and identities.

Second, our models confirm that there is a dark side of regional identity in the new Länder, evident in the effects of Attachment to the Land and the former GDR on dislike of foreigners. This result suggests that the findings on the exclusion component of collective identities can be transferred to the sub-national level, although this transferability obviously depends on the special situation in east Germany. A broader study is required to test the mechanism behind it, collecting, among other things, data on feelings of relative disadvantage in both parts of the country. What makes our results particularly relevant are their potential consequences for the political actions of people in Germany and in other countries. This includes first and foremost the question of the significance of regional and nativist attitudes for voting for radical right-wing parties. For Germany, for example, evidence suggests that apart from negative attitudes towards immigrants and other factors (e.g. Hansen and Olsen 2019), factors related to regional identity also affect the likelihood of voting for the radical right-wing party Alternative for Germany (AfD). These can be feelings of lack of recognition due to regional origin (e.g. Weisskircher 2020) or disenchantment with a political system that is perceived to be very distant from the regional situation (Betz and Habersack 2019). This leads directly to the question whether different dimensions of populism, such as anti-elitism, correlate with regional identity in the German Länder but also in other regions in Europe (van Hauwaert et al. 2019). How these correlations will develop in the future is likely to depend in part on how political parties are going to address regional identities.

Regarding research on integration and regional identity in federal countries, the next step should be a comparison of specific integration policies in Länder with a long historic tradition, such as Saxony or Bavaria, and in hyphenated Länder, such as North Rhine-Westphalia or Rhineland-Palatinate (see Hildebrandt and Trüdinger 2020 for an overview of the varying degrees of regional identity in the German Länder). People’s attitudes towards migrants should be taken into account, as well as the different proportions of migrants in the population.

Finally, we need cross-national comparative studies that test for a broad range of attitudinal and behavioural consequences of regional identity in other European regions, such as Catalonia, Scotland, or Flanders, where regional identity is much stronger than in Germany.

Notes

According to Tajfel and Turner (1986, pp. 19–20), if the own group performs worse than the foreign group in social comparisons, the individual can use three different strategies to nevertheless perceive the own group in a positive light: choosing another relevant object of comparison, choosing another relevant comparison dimension, or redefining social categories traditionally regarded as negative.

Mäs’ argument cannot be tested directly in our analysis, since the ALLBUS does not contain any questions about the extent to which east Germans feel disadvantaged in comparison to west Germans.

Some of the newly established Länder had already existed as independent Länder or as provinces of Prussia. Others were created by the Allies combining several Länder and/or Prussian provinces (see Hildebrandt and Trüdinger 2020 for an overview).

In the years 2000 (F = 9634 p < 0.01) and 2016 (F = 28,867 p < 0.001) this difference was significant.

The data were weighted by the relative share of the population of east and west Germany.

Due to the limited variance of the variable Attachment to Land (only about 3% of the respondents do not feel attached to their Land at all) no more than two bins can be calculated in Figure A-1.

References

Adam, I., and E. Hepburn. 2019. Intergovernmental relations on immigrant integration in multi-level states. A comparative assessment. Regional & Federal Studies 29 (5): 563–589.

Altemeyer, B. 1988. Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Antonsich, M. 2010. Exploring the correspondence between regional forms of governance and regional identity: The case of Western Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies 17 (3): 261–276.

Ariely, G. 2012. Globalization, immigration and national identity: How the level of globalization affects the relations between nationalism, constructive patriotism and attitudes towards immigrants? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 15 (4): 539–557.

Betz, H.G., and F. Habersack. 2019. Regional Nativism in East Germany. In The People and the Nation: Populism and Ethno-territorial Politics in Europe, ed. R. Heinisch, E. Massetti, and O. Mazzoleni. New York: Routledge.

Blank, T., and P. Schmidt. 2003. National identity in a united Germany: Nationalism or patriotism? An empirical test with representative data. Political Psychology 24 (2): 289–312.

Blumenthal, J.V. 2009. Das Kopftuch in der Landesgesetzgebung: Governance im Bundesstaat zwischen Unitarisierung und Föderalisierung [The headscarf in state legislation: State governance between unitarianisation and federalisation]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Bohrer, B., M.-T. Friehs, P. Schmidt, and S. Weick. 2019. Contacts between Natives and Migrants in Germany: Perceptions of the Native Population since 1980 and an Examination of the Contact Hypotheses. Social Inclusion 7 (4): 320–331.

Brewer, M.B. 1991. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17 (5): 475–482.

Brigevich, A. 2018. Regional identity and support for integration: An EU-wide comparison of parochialists, inclusive regionalist, and pseudo-exclusivists. European Union Politics 19 (4): 639–662.

Chacha, M. 2013. Regional attachment and support for European integration. European Union Politics 14 (2): 206–227.

Chernyha, L.T., and S.L. Burg. 2012. Accounting for the effects of identity on political behavior: Descent, strength of attachment, and preferences in the regions of Spain. Comparative Political Studies 45 (6): 774–803.

Curtis, K.A. 2014. Inclusive versus exclusive: A cross-national comparison of the effects of subnational, national, and supranational identity. European Union Politics 15 (4): 521–546.

Dalton, R.J., and S. Weldon. 2010. Germans divided? Political culture in a United Germany. German Politics 19 (1): 9–23.

Esses, V.M., J.F. Dovidio, A.H. Semenya, and L.M. Jackson. 2005. Attitudes toward immigrants and immigration: The role of national and international identity. In The Social Psychology of Inclusion and Exclusion, ed. D. Abrams, M.A. Hogg, and J.M. Marques, 317–337. New York: Psychology Press.

Galais, C., and I. Serrano. 2020. The effects of regional attachment on ideological self-placement: A comparative approach. Comparative European Politics 18: 487–509.

Grix, J. 2000. East German political attitudes: Socialist legacies v. situational factors a false antithesis. German Politics 9 (2): 109–124.

Guinjoan, M., and T. Rodon. 2014. Beyond identities: Political determinants of support for decentralization in contemporary Spain. Regional & Federal Studies 24 (1): 21–41.

Hainmueller, J., J. Mummulo, and Yiqing Yu. 2019. How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis 27 (2): 163–192.

Hansen, M.A., and J. Olsen. 2019. Flesh of the same flesh: A study of voters for the alternative for Germany (AfD) in the 2017 federal election. German Politics 28 (1): 1–19.

Van Hauwaert, S.M., C.H. Schimpf, and R. Dandoy. 2019. Populist demand, economic development and regional identity across nine European countries: Exploring regional patterns of variance. European Societies 21 (2): 303–325.

Hildebrandt, A., and E.-M. Trüdinger. 2020. History is not Bunk. Tradition, political economy and regional identity in the German Länder. German Politics. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2020.1749265.

Hogg, M.A., and D. Abrahams. 1988. Social identifications. A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes. London: Routledge.

Hogg, M.A. 2010. Social identity theory. In Encyclopedia of Identity, vol. 2, ed. R.L.M.A. JacksonHogg, 749–753. London: Sage.

Hogg, M.A., and G.M. Vaughan. 2018. Social Psychology, vol. 8. Harlow: Pearson.

Hooghe, M., and D. Stiers. 2020. Regional identity and support for restrictive attitudes on immigration. Evidence from a household population survey in Ghent (Belgium). Ethnic and Racial Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1782962.

Huddy, L. 2001. From Social to political identity: A critical examination of the social identity theory. Political Psychology 22 (1): 127–156.

Huddy, L., and A. Del Ponte. 2019. National identity, pride, and chauvinism–their origins and consequences for globalization attitudes. In Liberal Nationalism and Its Critics, ed. G. Gustavsson and D. Miller, 38–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jeffery, C., and D. Hough. 2009. Understanding post-devolution elections in Scotland and Wales in comparative perspective. Party Politics 15 (2): 219–240.

Kuntz, A., E. Davidov, and M. Semyonov. 2017. The dynamic relations between economic conditions and anti-immigrant sentiment: A natural experiment in times of the European economic crisis. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58 (5): 392–415.

Laufer, H., and U. Münch. 1998. Das föderative System der Bundesrepublik Deutschland [The federal system of the Federal Republic of Germany]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Medeiros, M., and Gauvin, J.-P. In this Issue. Two regionalisms, one mechanism: How identity shapes support for decentralization. Comparative European Politics.

Meyer, B., and P. Geschiere. 1999. Introduction. In Globalization and Identity Dialectics of flow and closure, ed. B. Meyer and P. Geschiere, 1–15. Oxford: Blackwell.

Mäs, M. 2005. Regionalismus, Nationalismus und Fremdenfeindlichkeit [Regionalism, nationalism and xenophobia]. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Mühler, K., and K.-D. Opp. 2007. Region-Nation-Europa: Die Dynamik regionaler und überregionaler Identifikation [Region-nation-Europe: The dynamics of regional and supra-regional identity]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Münch, U. 2016. Integrationspolitik der Länder – dringliche Zukunftsaufgabe im Umbruch [Integration policy of the Länder – The transformation of an urgent future task]. In Die Politik der Bundesländer. Zwischen Föderalismusreform und Schuldenbremse [Länder politics. Between federalism reform and debt brake], eds. A. Hildebrandt and F. Wolf, 365–390. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Neller, K. 2005. “Auferstanden aus Ruinen” Das Phänomen „DDR-Nostalgie” [“Risen from ruins” The phenomenon of “GDR nostalgia”]. In Wächst zusammen, was zusammengehört? Stabilität und Wandel politischer Einstellungen im wiedervereinigten Deutschland [Will what belongs together grow together? Stability and change in political attitudes in reunited Germany], ed. O.W. Gabriel, J.W. Falter, and H. Rattinger, 339–381. Nomos: Baden-Baden.

Neller, K. (2006) DDR-Nostalgie. Dimensionen der Orientierungen der Ostdeutschen gegenüber der ehemaligen DDR, ihre Ursachen und politischen Konnotationen [GDR nostalgia. Dimensions of east Germans’ attitudes towards the former GDR, their causes, and political connotations]. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Nicoli, F., T. Kuhn, and B. Burgoon. 2020. Collective identities, European Solidarity: identification patterns and preferences for European social insurance. JCMS 58 (1): 76–95.

Paasi, A. 2009. The resurgence of the ‘region’and ‘regional identity’: Theoretical perspectives and empirical observations on regional dynamics in Europe. Review of international studies 35 (1): 121–146.

Pettigrew, T.F. 1998. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology 49: 65–85.

Raijman, R., M. Semyonov, and P. Schmidt. 2003. Do foreigners deserve rights? Determinants of public views towards foreigners in Germany and Israel. European Sociological Review 19 (4): 379–392.

Schmidt, P., and A. Heyder. 2000. Wer neigt eher zu autoritärer Einstellung und Ethnozentrismus, die Ost- oder die Westdeutschen? – Eine Analyse mit Strukturgleichungsmodellen [Who is more susceptible to authoritarian attitudes and ethnocentrism, east or west Germans? – An analysis with structural equation modelling]. In Deutsche und Ausländer: Freunde, Fremde oder Feinde? Empirische Befunde und theoretische Erklärungen [Germans and foreigners: Friends, strangers or enemies? Empirical findings and theoretical explanations], ed. R. Alba, P. Schmidt, and M. Wasmer, 439–483. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Schmidt, P., and S. Weick. 2017. Kontakte und die Wahrnehmung von Bedrohungen besonders wichtig für die Einschätzung von Migranten: Einstellungen der deutschen Bevölkerung zu Zuwanderern von 1980 bis 2016 [Contacts and the perception of threats are particularly important for the evaluation of migrants: Positions of the German population towards immigrants from 1980–2016]. Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren 57: 1–7.

Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, A.Y. Tov, and P. Schmidt. 2004. Population size, perceived threat, and exclusion: A multiple-indicators analysis of attitudes toward foreigners in Germany. Social Science Research 33: 681–701.

Serrano, I. 2013. Just a matter of identity? Support for independence in Catalonia. Regional & Federal Studies 23 (5): 523–545.

Sinnott, R. 2005. An evaluation of the measurement of national, subnational and supranational identity in crossnational surveys. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18 (2): 211–223.

Svallfors, S. 2010. Policy feedback, generational replacement, and attitudes to state intervention: Eastern and Western Germany, 1990–2006. European Political Science Review 2 (1): 119–135.

Tajfel, H. 1974. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information 13 (2): 65–93.

Tajfel, H., and J. Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, ed. S. Worchel and W. Austin, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson Hall.

Thomsen, L., E.G.T. Green, and J. Sidanius. 2008. We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44: 1455–1464.

Verhaegen, S., Dupuy, C., and Van Ingelgom, V. In this issue. Experiencing and supporting institutional regionalization in Belgium: A normative and interpretive policy feedback perspective. Comparative European Politics.

Wagner, U., J.C. Becker, O. Christ, T.F. Pettigrew, and P. Schmidt. 2012. A longitudinal test of the relation between German Nationalism, patriotism, and out-group derogation. European Sociological Review 28 (3): 319–332.

Weisskircher, M. 2020. The strength of far-right AfD in Eastern Germany: The East-West divide and the multiple causes behind ‘populism.’ The Political Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12859.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hildebrandt, A., Trüdinger, EM. Belonging and exclusion: the dark side of regional identity in Germany. Comp Eur Polit 19, 146–163 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00230-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-020-00230-5