Abstract

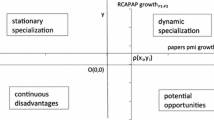

This paper provides global empirical evidence on cross-country differences in scientific and technical publications. Its purpose is to model the future of scientific knowledge monopoly in order to understand whether the impressive growth experienced by latecomers in the industry has been accompanied by a similar catch-up in scientific capabilities and knowledge contribution. The empirical evidence for the period 1994–2010 is based on 41 panels which together consist of 99 countries. The large dataset allows us to disaggregate countries into fundamental characteristics based on income levels (high-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income and low-income), legal origins (English common-law, French civil-law, German civil-law and Scandinavian civil-law) and regional proximity (South Asia, Europe and Central Asia; East Asia and the Pacific; Middle East and North Africa; Latin America and the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa). Three main issues are investigated: the presence or not of catch-up processes, the speed of the catch-up processes and the time needed for a complete elimination of country differences in scientific and technical publications. The findings based on absolute and conditional catch-up patterns broadly show that advanced countries will continue to dominate in scientific knowledge contribution. Policy implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The rising cost of traditional scientific scholarly communication coupled with the increase of widely available internet communication tools such as the World Wide Web (www) have provided a catalyst for a revolution in the exchange of scientific and technical information (Esler and Nelson, 1998).

World Intellectual Property Organisation.

The coefficient of determination (R²) on which the computation of the Variance Inflation Factor is based is not an information criterion in the GMM output. Hence, we gauge multicollinearity with a simple correlation analysis. Moreover, the highest degree of substitution between pairs of independent variables is 56.6 %.

“We also demonstrate that more plausible results can be achieved using a system GMM estimator suggested by Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998). The system estimator exploits an assumption about the initial conditions to obtain moment conditions that remain informative even for persistent series, and it has been shown to perform well in simulations. The necessary restrictions on the initial conditions are potentially consistent with standard growth frameworks, and appear to be both valid and highly informative in our empirical application. Hence we recommend this system GMM estimator for consideration in subsequent empirical growth research”. Bond et al. (2001, pp. 3–4).

In the one-step approach, the residuals are assumed to be homoscedastic.

We have nine 2-year non-overlapping intervals: 1994; 1995–1996; 1997–1998; 1999–2000; 2001–2002; 2003–2004; 2005–2006; 2007–2008; 2009–2010. Owing to data and periodical constraints, the first interval is short of 1 year.

Consistent with Asongu (2013a), in addition to the two justifications provided above, we may cite three additional premises on which this choice of the 2-year NOI is based. First, NOI with a higher numerical value (say 3-year NOI) absorbs more short-run disturbances at the cost of weakening the model. Hence, the preference for the 2-year NOI over the 3/4/5-year NOI is further justified by the need to exploit the time series dimensions as much as possible. Second, a corollary to the above point is the positive side of additional degrees of freedom necessary for conditional convergence modelling. Hence, given the time span of 17 years, a higher order of NOI will greatly limit conditional convergence analysis. Third, heuristically from a visual analysis, the rate of scientific publications does not show evidence of persistent business cycle (short term) disturbances that require higher NOI.

Some balance in the two-way flow of staff will ensure that source countries do not experience a loss of staff and destination countries benefit from lack of staff. This will minimize the negative externalities of professionals’ flow from source to receiving countries.

These fellowships by developed countries to developing countries could be scaled-up.

References

Agbor, JA. 2015: How does colonial origin matter for economic performance in SubSaharan Africa? In Growth and Institutions in African Development, Fosu, AK (ed) 2015, Chapter 13, pp. 309–327, Routledge Studies in Development Economics: New York.

Albuquerque, EM. 2000: Scientific infrastructure and catching-up process: Notes about a relationship illustrated by science and technology statistics. The Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association.

Amavilah, VHS. 2009: Knowledge of African countries: Production and value of doctoral dissertations. Applied Economics 41(8): 977–989.

Andrés, AR and Asongu, SA. 2013: Global dynamic timelines for IPRs harmonization against software piracy. Economics Bulletin 33(1): 874–880.

Apergis, N, Christou, C and Miller, SM. 2010: Country and Industry Convergence in Equity Markets: International Evidence from Club Convergence and Clustering. Department of Banking and Financial Management, University of Piraeus, Greece.

Arellano, M and Bond, S. 1991: Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies 58(2): 277–297.

Arellano, M and Bover, O. 1995: Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics 68(1): 29–52.

Asongu, SA. 2013a: Modeling the future of knowledge economy: Evidence from SSA and MENA countries. Economics Bulletin 33(1): 612–624.

Asongu, SA. 2013b: The ‘Knowledge Economy’-finance nexus: How do IPRs matter in SSA and MENA countries? Economics Bulletin 33(1): 78–94.

Asongu, SA. 2013c: Harmonizing IPRs on software piracy: Empirics of trajectories in Africa. Journal of Business Ethics 118(1): 45–60.

Asongu, SA. 2013d: Real and monetary policy convergence: EMU crisis to the CFA zone. Journal of Financial Economic Policy 5(1): 20–38.

Asongu, SA. 2014a: African development: Beyond income convergence. South African Journal of Economics 82(3): 334–353.

Asongu, SA. 2014b: Software piracy, inequality and the poor: Evidence from Africa. Journal of Economic Studies 41(4): 526–553.

Asongu, SA. 2014c: Globalization and health worker crisis: What do wealth-effects tell us? International Journal of Social Economics 41(12): 1243–1264.

Asongu, SA. 2015a: Knowledge Economy gaps, policy syndromes, and catch-up strategies: Fresh South Korean lessons to Africa. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. doi: 10.1007/s13132-015-0321-0.

Asongu, SA. 2015b: The comparative economics of knowledge economy in Africa: Policy benchmarks, syndromes, and implications. Journal of the Knowledge Economy. doi:10.1007/s13132-015-0273-4.

Asongu, SA. 2015c: Fighting software piracy in Africa: How do legal origins and IPRs protection channels matter? Journal of the Knowledge Economy 6(4): 682–703.

Asongu, SA. and Nwachukwu, JC. 2015: Revolution empirics: Predicting the Arab Spring. Empirical Economics. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00181-015-1013-0.

Balconi, M, Brusoni, S and Orsenigo, L. 2010: In defense of the linear model: An essay. Research Policy 39(1): 1–13.

Barro, R. 1991: Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics 196(2/May): 407–443.

Barro, RJ and Sala-i-Martin, X. 1992: Convergence. Journal of Political Economy 100(2): 223–251.

Barro, RJ and Sala-i-Martin, X. 1995: Economic Growth. The MIT Press: Cambridge.

Baumol, WJ. 1986: Productivity, growth, convergence and welfare: what the long run data show. American Economic Review 76(5): 1072–1085.

Bezmen, TL and Depken, CA. 2004: The impact of software piracy on economic development. Working Paper. Francis Marion University.

Blundell, R and Bond, S. 1998: Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87(1): 115–143.

Bond, S, Hoeffler, A and Tample, J. 2001: GMM Estimation of Empirical Growth Models. University of Oxford: Oxford.

Bruno, G, De Bonis, R and Silvestrini, A. 2012: Do financial systems converge? New evidence from financial assets in OECD countries. Journal of Comparative Economics 40(1): 141–155.

Chandra, DS and Yokoyama, K. 2011: The role of good governance in the knowledge-based economic growth of East Asia – A study on Japan, Newly Industrialized Economies, Malaysia and China. Graduate School of Economics, Kyushu University.

D’Este, P and Patel, P. 2007: University-Industry Linkages in the UK: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy 36(9): 1295–1313.

Esler, SL and Nelson, M. 1998: Evolution of scientific and technical information distribution. Journal of the American Society of Information Science 49(1): 82–91.

Fung, MK. 2009: Financial development and economic growth: Convergence or divergence? Journal of International Money and Finance 28(1): 56–67.

Islam, N. 1995: Growth empirics: A panel data approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(4): 1127–1170.

Kim, EM. 1997: Big Business, Strong State: Collusion and Conflict in South Korean Development, 1960–1990. State University of New York Press: New York.

Kim, EM and Kim, PH. 2014: The South Korean Development Experience: Beyond Aid. Critical Studies of the Asia Pacific, Palgrave Macmillan.

Kim, L and Nelson, R. 2000: Technology, Learning and Innovation: Experiences of Newly Industrializing Economies. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Kim, Y, Lee, K, Park, WG and Choo, K. 2012: Appropriate intellectual property protection and economic growth in countries at different levels of development. Research Policy 41(2): 358–375.

La Porta, R, Lopez-de-Silanes, F, Shleifer, A and Vishny, RW. 1998: Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6): 1113–1155.

Lee, K. 2009: How Can Korea be a Role Model for Catch-up Development? A ‘Capabilitybased’ View”. UN-WIDER Research Paper No. 2009/34, Helsinki.

Mankiw, NG, Romer, D and Weil, DN. 1992: A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(May): 407–437.

Mayer-Foulkes, D. 2010: “Divergences and Convergences in Human Development”. UNDP Human Development Research Paper No. 2010/20, New York.

Mazzoleni, R. 2008: Catching up and academic institutions: A comparative study of past national experiences. The Journal of Development Studies 44(5): 678–700.

Mazzoleni, R and Nelson, R. 2007: Public research institutions and economic catch-up. Research Policy 36(10): 1512–1528.

Miller, SM and Upadhyay, MP. 2002: Total factor productivity and the convergence hypothesis. Journal of Macroeconomics 24(2): pp. 267–286.

Morrison, A, Cassi, I and Rabellotti, R. 2009: Catching-up Countries and the Geography of Science in the Wine Industry. Copenhagen Business School, 2009 Summer Conference.

Mowery, DC and Sampat, BN. 2005: Universities and Innovation. In: The Oxford Handbook on Innovation, Fagerberg, J, Mowery, D and Nelson, R. (eds) Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Murray, F and Stern, S. 2005: Do Formal Intellectual Property Rights Hinder the Free Flow of Scientific Knowledge? An Empirical Test of the Anti-Commons Hypothesis. NBER Working Paper No. 11465, Cambridge.

Narayan, PK, Mishra, S and Narayan, S. 2011: Do market capitalization and stocks traded converge? New global evidence. Journal of Banking and Finance 35(10): 2771–2781.

Packer, C, Labonté, R and Spitzer, D. 2007, August: Globalization and Health Worker Crisis. Globalization and Health Knowledge Network Research Paper, Ottawa.

Pritchett, L. 1997: Divergence, big time. Journal of Economic Perspectives 11(3): 3–17.

Tchamyou, SV. 2015: The role of knowledge economy in African business. African Governance and Development Institute Working Paper, No. 15/049, Yaoundé.

Wantchékon, L. 2013: African School of Economics Academic Project. Princeton University (USA) and IERPE (Benin).

Weber, AS. 2011: The role of education in knowledge economies in developing countries. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15(2011): 2589–2594.

World Bank 2007: Building Knowledge Economies. Advanced Strategies for Development. World Bank Institute Development Studies. Washington DC.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Paul Wachtel and referees for their constructive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Determination of Fundamental Characteristics and Catch-Up Panels

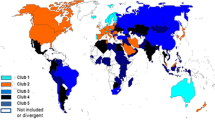

We devote some space to discussing the determination of fundamental characteristics and corresponding catch-up panels. Consistent with Asongu (2013c), it is unlikely to find catch-up processes within a heterogeneous set of countries. Recent studies have stressed the relevance of a variety of contexts and historical periods (Mazzoleni, 2008; Mazzoleni and Nelson, 2007) and geographical areas (Morrison et al., 2009) in the catch-up process. Accordingly, the determination of fundamental characteristics should be based on factors that naturally determine scientific and technical publications such as R&D budgets, degree of IPRs protections, rate of higher education enrolment, inter alia. However, as cautioned by Asongu (2013c), macroeconomic fundamental characteristics have the drawback of being time-dynamic. Hence, the same threshold may not be consistent over time, especially within a horizon of 17 years. In accordance with the literature (Narayan et al., 2011; Asongu, 2013c), we shall take a minimalistic approach in the determination of fundamental characteristics and control for fundamental determinants of scientific publications in the estimations. The main fundamental characteristics are based on: legal origins, income levels and regional proximity, while corresponding catch-up panels are derived from the fundamental characteristics.

First, the foundation of legal origin as a fundamental characteristic of scientific publications is based on the emphasis that legal origins place on private property rights vis-à-vis those of the state (La Porta et al., 1998). According to Agbor (2015), the educational channel substantially explains variations in economic performance among countries with different legal traditions in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In essence, the underlying logic for this segmentation is that the institutional web of informal norms, formal rules and enforcement characteristics affect the educational and research environments. Adopted legal origins include English common-law, French civil-law, German civil-law and Scandinavian civil-law.

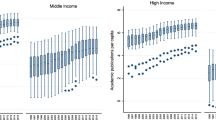

Second, assessing scientific publications with income-level dynamics is deeply rooted in the intuition that wealthy nations have the tendency to allocate more funds to research activities. The income levels include High-income, Upper-middle-income, Lower-middle-income and Low-income.

Third, regional proximity is also fundamental in the catch-up process because Morrison et al. (2009) have postulated that differences over time and across geographical areas also explain the catch-up process. Moreover, the inclusion of this characteristic is broadly consistent with the empirical underpinnings of the catch-up literature (Narayan et al., 2011; Asongu, 2013d; Andrés and Asongu, 2013). The regions include South Asia, Europe and Central Asia; East Asia and the Pacific; Middle East and North Africa; Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean.

From the fundamental characteristics, 41 catch-up panels are derived. These include (i) 10 on wealth-effects (High-income, High-income and Upper-middle-income, High-income and Lower-middle-income, High-income and Low-income, Upper-middle-income, Upper-middle-income and Lower-middle-income, Upper-middle-income and Low-income, Lower-middle-income, Lower-middle-income and Low-income, Low-income); (ii) 10 on legal origins (English common-law, English common-law and French civil-law, English common-law and German civil-law, English common-law and Scandinavian civil-law, French civil-law, French civil-law and German civil-law, French civil-law and Scandinavian civil-law, German civil-law, German civil-law and Scandinavian civil-law and Scandinavian civil-law); and (iii) 21 on regional proximity (South Asia, South Asia and Europe and Central Asia, South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific, South Asia and Middle East and North Africa, South Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia, Europe and Central Asia and East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia and Middle East and North Africa, Europe and Central Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific, East Asia and the Pacific and Middle East and North Africa, East Asia and the Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia and the Pacific and Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, Middle East and North Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Latin America and the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa). There is no North American group. The USA, Mexico and Canada are included in the ECA group. Hence, the ECA may coincide with high-income countries. While low-income countries are not substantially represented, ‘latecomers in the industry’ as motivated in the introduction also refers to middle-income countries.

Appendix 2

See Table A1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asongu, S.A., Nwachukwu, J.C. A Brief Future of Time in the Monopoly of Scientific Knowledge. Comp Econ Stud 58, 638–671 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-016-0008-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-016-0008-y