Abstract

Against the background of seriously underfunded infrastructure and the risk of resulting lower competitiveness of the European Economic Area, the European Commission aims to incentivise private and institutional investments in infrastructure, thereby laying one main focus on pension funds and insurance companies. At the same time, insurers seek attractive long-term investment opportunities with stable cash flows that help match their long-term liabilities as an alternative to long-term government bonds, which currently suffer from low interest rates. However, financing volumes are still low, indicating the existence of certain investment barriers. The aim of this paper is to study these major barriers to infrastructure investments with a focus on the insurance industry and Solvency II, along with the impact of several European initiatives that are intended to reduce barriers, thereby also providing numerical examples regarding solvency capital requirements.

Source: Own presentation based on Article 164a (European Commission 2016, p. 4)

Source: Own calculations based on input data in Table 1 as well as the following assumptions: coupon 3 per cent, maturity 1 to 50, face value 100, market value 100. a SCR for qualifying and non-qualifying infrastructure bond investments for credit quality step (CQS) 1 (amendment in the case of qualifying infrastructure: see Table 1). b SCR for qualifying infrastructure bond investment with and without spread risk for credit quality step (CQS) 1 (no spread risk charge in the case where of Member States' central government bonds or specifically structured bonds or loans, e.g. by the EIB)

Source: Own presentation based on EIB (2012, pp. 10, 12), http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/ financial_operations/investment/europe_2020/index_en.htm (accessed 2 February 2015)

Source: Own presentation based on European Commission (2014c, p. 7)

Source: Own calculations based on input data in Table 1 as well as the following assumptions: Coupon 3 per cent, maturity 1 to 50, face value 100, market value 100

Source: Own calculations based on input data in Table 1 as well as the following assumptions: Coupon 3 per cent, maturity 1 to 50, face value 100, market value 100

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Inderst (2013, pp. 5–6). In the European Union (EU), annual infrastructure investments amount to 2.6 per cent of the European GDP (based on the GDP of 2010) for the years of 1992–2011, whereas estimated needs for a projected growth from 2013–2030 require an investment volume of 3.1 per cent (Dobbs et al., 2013, pp. 12–13). Inderst (2013, p. 12) outlines different growth scenarios, whereby the required annual amount of European infrastructure investments varies between 470 billion euros (2.6 per cent of GDP in 2010) and 810 billion euros (4.5 per cent of GDP in 2010).

World Economic Forum (2012).

http://www.insuranceeurope.eu/insurancedata (accessed 24 December 2015).

European Commission (2014a, p. 2).

http://ec.europa.eu/finance/insurance/solvency/solvency2/index_en.htm (accessed 11 November 2015).

Gatzert and Kosub (2014).

Inderst (2013, pp. 37–40).

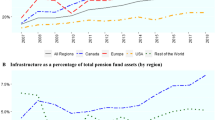

Della Croce and Yermo (2013).

Bassanini et al. (2011, pp. 3–4).

The authors advise policy makers to undertake certain changes such as (i) the creation of a new asset class for infrastructure, (ii) the allocation of 15 to 20 billion euros to support the EU2020 Project Bond Initiative and (iii) to create a Pan-European public infrastructure bond agency to improve liquidity.

E.g. Gatzert and Kosub (2014) for an overview of the (empirical) literature.

Berdin and Gründl (2015, p. 413).

Gatzert and Kosub (2014, pp. 356–357, 362).

The SCR can either be calculated based on the so-called standard model provided by the regulatory authorities or an internal model, which more adequately reflects the insurer’s individual risk situation and which must be certified by the regulatory authority.

In particular, the symmetric adjustment has the following two objectives: to “avoid that insurance and reinsurance undertakings are unduly forced to raise additional capital or sell their investments as a result of adverse movements in financial markets” and to “discourage or avoid fire sales which would further negatively impact the equity prices i.e. prevent a pro-cyclical effect of the capital requirements which would in times of stress lead to an increase of capital requirements and hence have a potential destabilising effect on the economy”. (EIOPA, 2014, p. 19). The corresponding formula can be found in EIOPA (2014 p. 19).

Criteria required for investments to be recognised as “strategic participation” are listed in Article 171 in European Commission (2015a, p. 110) and refer to equity investments of strategic nature as investments that are likely to be less volatile than investments in other equities for the following 12 months, caused by i) the nature of the investment and ii) the influence of the participation. Additionally, strategic investments need to fulfil various requirements, e.g. the existence of a clear strategy to continue holding the participation for a long period (European Commission, 2015a, p. 110).

Credit quality steps represent a standardised categorisation of credit ratings from external credit assessment institution (ECAI) using an objective scale of credit quality steps, which is intended to increase comparability and transparency (e.g. Moody’s “Aaa” corresponds to CQS 0; 1 (“Aa”), 2 (“A”), 3 (“Baa”), 4 (“Ba”), 5 (“B”), and 6 (“Caa”, “Ca”, “C”)).

European Commission (2015a, Article 176).

As we focus on the asset side, the shock scenario only refers to the upside movement of the interest rate curve, reducing the market value of bonds.

The risk-free rate published and regularly updated by EIOPA is based on interest rate swap rates, government bond rates and corporate bond rates traded in deep, liquid and transparent markets (EIOPA 2016a, p. 26); further details on the risk-free rate can be found on https://eiopa.europa.eu/regulation-supervision/insurance/solvency-ii-technical-information/risk-free-interest-rate-term-structures).

See, e.g. Gatzert and Kosub (2016) for a comprehensive discussion of risks and risk management associated with renewable energy investments from the investors’ perspective.

Della Croce and Yermo (2013, p. 28).

Inderst (2013, pp. 38–39).

Della Croce et al. (2011, p. 27).

Narbel (2013, p. 15).

Non-recourse financing describes a financing structure where the lender (i.e. bank) is only entitled to receive the payments from the project’s profit and not from other assets of the borrower. This makes renewable energy more risky, as renewables are exposed to various risk factors (e.g. Gatzert and Kosub, 2016).

E.g. Gatzert and Kosub (2016) for risks and risk management of renewables.

Inderst (2009, p. 23).

European Commission, (2014a, pp. 2–3), https://eiopa.europa.eu/Pages/News/EIOPA-advises-to-set-up-a-new-asset-class-for-high-quality-infrastructure-investments-under-Solvency-II.aspx (accessed 28 December 2015); European Commission (2016).

European Commission (2016, p. 4): “Infrastructure project entity’ means an entity which is not permitted to perform any other function than owning, financing, developing or operating infrastructure assets, where the primary source of payments to debt providers and equity investors is the income generated by the assets being financed”.

European Commission (2016, p. 8).

In regard to using 77 per cent of the symmetric adjustment, EIOPA (2015, p. 14) states: “…to scale the symmetric risk charge linearly according to the selected equity risk charge. If, for example, 35 per cent was chosen, then the symmetric adjustment would be 35 divided by 39 multiplied by the symmetric adjustment for type 1 and type 2 equities. The underlying rationale is that the lower equity risk charge results from lower price volatility, which should be reflected in a reduced symmetric adjustment (especially if a value at the lower end of the range was chosen)”.

European Commission (2015a).

See European Commission (2016, p. 9) and https://eiopa.europa.eu/Pages/News/EIOPA-advises-to-set-up-a-new-asset-class-for-high-quality-infrastructure-investments-under-Solvency-II.aspx (accessed 28 December 2015).

Article 180 (2) (European Commission, 2015a, p. 118).

Berdin and Gründl (2015, pp. 388, 395).

http://www.gdv.de/2015/07/vorschlaege-der-eiopa-gehen-nicht-weit-genug/ (accessed 21 July 2015).

EIOPA (2015, p. 14).

EIOPA (2015).

EIOPA (2016b, pp. 5–7, 20).

EIOPA (2016b, p. 20).

EIOPA (2016b, pp. 7, 20–21).

EIB (2012, p. 4); Heymann (2013, p. 1), http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/financial_operations/ investment/europe_2020/index_en.htm (accessed 2 February 2015).

Heymann (2013, p. 8).

EIB (2012, p. 5), http://eib.europa.eu/products/blending/project-bonds/index.htm (accessed 2 February 2015).

EIB (2012, p. 5).

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/financial_operations/investment/europe_2020/index_en.htm (accessed 8 February 2016).

Heymann (2013, p. 1).

EIB (2012, p. 8).

Heymann (2013, p. 4).

EIB (2012, p. 8).

Heymann (2013, p. 5).

Heymann (2013, p. 5).

European Commission (2014c, p. 7); European Commission (2014b, p. 3), http://ec.europa.eu/news/2014/11/20141126_de.htm (accessed 5 February 2015). Note that in September 2016, the president of the European Commission announced a proposal “to extend its successful European Fund for Strategic Investments, at the heart of its Investment Plan for Europe, to increase its firepower and reinforce its strengths; and to set up a new European External Investment Plan (EIP) to encourage investment in Africa and the EU Neighbourhood to strengthen our partnerships and contribute to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals” (http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-3002_en.htm (accessed 2 November 2016).

Wettach et al. (2014).

European Commission (2014c, p. 5), http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/30/us-eu-fund-idUSKBN0L319Q20150130 (accessed 5 February 2015).

European Commission (2014c, p. 4), http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/30/us-eu-fund-idUSKBN0L319Q20150130 (accessed 5 February 2015).

European Commission (2014c, p. 12).

Wettach et al. (2014).

European Commission (2015b).

http://ec.europa.eu/priorities/jobs-growth-investment/plan/eipp/index_en.htm (accessed 16 November 2015).

European Commission (2014c, p. 8).

European Commission (2014b, p. 14).

Bassanini et al. (2011, p. 3).

While the EFSI operations have only recently started, experiences from the EU2020 Project Bond Initiative are already available.

EPEC (2012, p. 3).

Presumably, the location of the Castor project was disadvantageous, leading to several minor earthquakes in Spain. As a result, the Spanish government stopped the operations of this project and the Spanish government reimbursed 1.35 billion euros to the project responsible (Fitch, 2014; Wettach et al., 2014; http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/09/27/spain-gas-idUSL5N0HN0OZ20130927 [accessed 5 February 2015]).

Fitch (2014.

References

Bassanini, F., Del Bufalo, G. and Reviglio, E. (2011) Financing Infrastructure in Europe—Project Bonds, Solvency II and the “Connecting Europe” Facility, Eurofi Financial Forum 2011, Wroclaw, Poland, 15–16 September.

Berdin, E. and Gründl, H. (2015) ‘The effects of a low interest rate environment on life insurers’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 40(2): 385–415.

Bird, R., Liem, H. and Thorp, S. (2012) ‘Infrastructure: real assets and real returns’, European Financial Management 20(4): 802–824.

Bitsch, A., Buchner, A. and Kaserer, C. (2010) ‘Risk, return and cash flow characteristics of infrastructure fund investments’, EIB Papers 15(1): 106–137.

Blanc-Brude, F. (2013) Towards efficient benchmarks for infrastructure equity investments, EDHEC-Risk Institute, from www.edhec.com, accessed 2 December 2016.

Blanc-Brude, F., Hasan, M. and Ismail, O.R.H. (2014) Unlisted infrastructure debt valuation & performance measurement, EDHEC-Risk Institute, from www.edhec.com, accessed 2 December 2016.

Della Croce, R. (2011) Pension funds investment in infrastructure, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions No. 13, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Della Croce, R., Kaminker, C. and Stewart, F. (2011) The role of pension funds in financing green growth initiatives, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions No. 10. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Della Croce, R. and Yermo, J. (2013) Institutional investors and infrastructure financing, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions No. 36. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Dobbs, R., Pohl, H., Lin, D.-Y., Mischke, J., Garemo, N., Hexter, J., Matzinger, S., Palter, R. and Nanavatty, R. (2013) Infrastructure productivity: how to save $1 trillion a year, McKinsey Global Institute, from www.mckinsey.com, accessed 2 October 2016.

European Commission (2010) Communication from the Commission: Europe 2020—a strategy for smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth, from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52010DC2020&from=en, accessed 2 February 2015.

European Commission (2014a) Solvency II delegated act—frequently asked questions, from http://europa.eu, accessed 2 April 2015.

European Commission (2014b) The Investment Plan: questions and answers, from http://europa.eu, accessed 4 February 2015.

European Commission (2014c) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank: an Investment Plan for Europe, COM(2014) 903 final, from http://europa.eu, accessed 4 February 2015.

European Commission (2015a) ‘Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35 of 10 October 2014 supplementing Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the taking-up and pursuit of the business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II)’, Official Journal of the European Union L 12, 17.1.2015, pp. 1–797, from http://europa.eu, accessed 4 February 2015.

European Commission (2015b) ‘Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/1214 of 22 July 2015 creating the European Investment Project Portal and setting out its technical specifications’, Official Journal of the European Union L 196, 24.7.2015, p. 23–25, from http://europa.eu, accessed 16 November 2015.

European Commission (2016) ‘Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/467 of 30 September 2015 amending Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35 concerning the calculation of regulatory capital requirements for several categories of assets held by insurance and reinsurance undertakings’, Official Journal of the European Union L 85, 1.4.2016, pp. 6–19. http://europa.eu, accessed 9 September 2015.

EIOPA (2014) The underlying assumptions in the standard formula for the Solvency Capital Requirement calculation, EIOPA-14-322, Frankfurt: European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, from https://eiopa.europa.eu/Publications/Standards/EIOPA-14-322_Underlying_Assumptions.pdf, accessed 13 October 2016.

EIOPA (2015) Final report on Consultation Paper No. 15/004 on the call for advice from the European Commission on the identification and calibration of infrastructure investment risk categories, EIOPA-BoS-15-223, Frankfurt: European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, from https://eiopa.europa.eu, accessed 12 November 2015.

EIOPA (2016a) Technical documentation of the methodology to derive EIOPA’s risk-free interest rate term structures, EIOPA-BoS-15/035, Frankfurt: European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, from https://eiopa.europa.eu, accessed 9 September 2016.

EIOPA (2016b) Final report on Consultation Paper No.16/004 on the request to EIOPA for further technical advice on the identification and calibration of other infrastructure investment risk categories, i.e. infrastructure corporates, EIOPA-16-490, Frankfurt: European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, from https://eiopa.europa.eu, accessed 9 September 2016.

EIB (2012) An outline guide to project bonds credit enhancement and the Project Bond Initiative, Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, from http://www.eib.org, accessed 7 February 2015.

EPEC (2012) Financing PPPs with project bonds: issues for public procuring authorities, Luxembourg: European PPP Expertise Centre, from http://www.eib.org, accessed 4 February 2015.

Finkenzeller, K., Dechant, T. and Schäfers, W. (2010) ‘Infrastructure: a new dimension of real estate? An asset allocation analysis’, Journal of Property Investment & Finance 28(4): 263–274.

Fitch (2013) Fitch assigns castor gas storage bonds ‘BBB + ’ final rating, from https://www.fitchratings.com, accessed 7 February 2015.

Fitch (2014) Fitch downgrades Castor gas storage bonds to ‘BB + ’; maintains on RWN, from https://www.fitchratings.com, accessed 5 February 2015.

Gatzert, N. and Kosub, T. (2014) ‘Insurers’ investment in infrastructure: overview and treatment under Solvency II’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 39(2): 351–372.

Gatzert, N. and Kosub, T. (2015) ‘Determinants of policy risks of renewable energy investments’, International Journal of Energy Sector Management (forthcoming).

Gatzert, N. and Kosub, T. (2016) ‘Risks and risk management of renewable energy projects: the case of onshore and offshore wind parks’, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 60: 982–998.

Gatzert, N. and Vogl, N. (2016) ‘Evaluating investments in renewable energy projects under policy risks’, Energy Policy, 95: 238–252.

Heymann, E. (2013) Project bond initiative: project selection the key to success, Frankfurt: Deutsche Bank Research, from http://www.dbresearch.de, accessed 3 February 2015.

IMF (2014) Germany—selected issues, IMF Country Report No. 14/217, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, from http://www.imf.org, accessed 3 February 2015.

Inderst, G. (2009) Pension fund investment in infrastructure, OECD Working Papers on Insurance and Private Pensions No. 32, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Inderst, G. (2010) ‘Infrastructure as an asset class’, EIB Papers 15(1): 71–105.

Inderst, G. (2013) Private infrastructure finance and investment in Europe, EIB Working Papers 2013/02, Luxembourg: European Investment Bank.

Kaminker, C., Kawanishi, O., Stewart, F., Caldecott, B. and Howarth, N. (2013): Institutional investors and gre e n infrastructure investments: selected case studies, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions No. 35, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Narbel, P. (2013) The likely impact of Basel III on a bank’s appetite for renewable energy financing, NHH Department of Business and Management Science Discussion Paper 2013/10, Bergen, Norway: Norwegian School of Economics.

Norton Rose Fulbright (2014) European infrastructure opportunities—an investment plan for Europe, from http://www.nortonrosefulbright.com, accessed 2 February 2015.

Peng, H. W. and Newell, G. (2007) ‘The significance of infrastructure in investment portfolios’, paper presented at the Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Conference, 21–24 January 2007, Fremantle, Australia.

Reviglio, E. (2012) ‘Global perspectives for project financing, financing future infrastructures’, paper presented at the Joint EC-EIB/EPEC Private Sector Forum, Brussels, 6 June 2012.

Rödel, M. and Rothballer, C. (2012) ‘Infrastructure as hedge against inflation—fact or fantasy?’, The Journal of Alternative Investments 15(1): 110–123.

Rothballer, C. and Kaserer, C. (2012) ‘The risk profile of infrastructure investments: challenging conventional wisdom’, The Journal of Structured Finance 18(2): 95–109.

Schwarz, G., Meier, D. and Schepers, F. (2011) Solvency II—eine strategische und kulturelle Herausforderung, Bain & Company, from http://www.bain.de, accessed 3 February 2015.

Shearman & Sterling LLP (2014) Basel III framework: net stable funding ratio, from www.shearman.com, accessed 4 February 2015.

Special Task Force (2014) Special Task Force (Member States, Commission, EIB) on Investments in the EU, Annex 2—project lists from Member States and the Commission, from http://ec.europa.eu, accessed 4 February 2015.

Turner, G., Roots, S., Wiltshire, M., Trueb, J., Brown, S., Benz, G. and Hegelbach, M. (2013) Profiling the Risks in Solar and Wind, Bloomberg and Swiss Re, from http://about.bnef.com/, accessed 30 June 2014.

Wettach, S., Kamp, M. and Ramthun, C. (2014) Junckers 315-Milliarden-Idee: das Investitionspaket sucht Projekte, from http://www.wiwo.de/politik/europa/junckers-315-milliarden-idee-das-investitionspaket-sucht-projekte-seite-all/11112858-all.html, accessed 5 February 2015.

World Bank (2014) Public–private partnerships reference guide, Version 2.0, Washington, DC: World Bank, from http://www.worldbank.org/, accessed 13 February 2015.

World Economic Forum (2012) Strategic infrastructure: steps to prioritize and deliver infrastructure effectively and efficiently, Cologny, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, from http://www.weforum.org, accessed 17 February 2016.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank two anonymous referees for valuable comments and suggestions on an earlier version of the paper. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support by the Emerging Fields Initiative of FAU (EFI-project “Sustainable Business Models in Energy Markets”) and the German Insurance Science Association (DVfVW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gatzert, N., Kosub, T. The Impact of European Initiatives on the Treatment of Insurers’ Infrastructure Investments Under Solvency II. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 42, 708–731 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-017-0042-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-017-0042-7