Abstract

Targeting remains a highly contentious aspect of social protection design, despite the growing body of evidence on various targeting mechanisms. While targeting is often framed as identifying the poorest households within limited budgets, such decisions are inherently political and shaped by notions of social justice. This in-depth study of a contested cash transfer model in Zambia finds that local ideas of deservingness led to the rejection of eligible fit-for-work recipients, and changes to the targeting model to prioritise incapacitated households. The analysis draws on interviews with government and policy actors, as well as focus group discussions in communities receiving cash transfers. Applying van Oorschot’s deservingness heuristic to this data reveals that the criterion of control (of circumstance) was prioritised by local level respondents. The paper argues that popular perceptions of deservingness—and the broader social justice implications—need to be taken seriously in the design and analysis of targeting.

Résumé

Le ciblage reste un aspect très controversé du système de protection sociale, malgré le nombre croissant de preuves concluantes concernant divers mécanismes de ciblage. Alors que le ciblage est souvent conçu comme l'identification des ménages les plus pauvres qui disposent de budgets limités, ce type de décision est intrinsèquement politique et façonné par la notion de justice sociale. Cette étude approfondie d'un modèle de transfert monétaire contesté en Zambie révèle que les idées qui prévalent au niveau local en matière de mérite ont conduit au rejet des bénéficiaires éligibles aptes au travail et à des modifications du modèle de ciblage pour donner la priorité aux ménages inaptes. L'analyse s'appuie sur des entretiens avec des acteurs gouvernementaux et politiques, ainsi que sur des discussions de groupe dans les communautés recevant des transferts monétaires. En appliquant l'heuristique de mérite de Van Oorschot à ces données, nous découvrons que le critère de contrôle (de circonstance) a été priorisé par les participants au niveau local. L’article soutient que les perceptions populaires relative au mérite - et ses ramifications en matière de justice sociale - doivent être prises au sérieux dans la conception et l'analyse du ciblage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The distinction between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor has long shaped the targeting of welfare and social protection, yet studies of public attitudes to deservingness have so far largely been limited to Western Europe and the USA (de Swaan 1988; van Oorschot 2006; van Oorschot et al. 2017; Will 1993). The dominance of an instrumental and technocratic approach to poverty targeting in development policy has led to a narrow conceptualisation of cost–benefit analysis focused on the efficient use of scarce resources (Devereux et al. 2017; Grosh et al. 2008). This residual approach to poverty reduction is underpinned by a methodological individualism that situates the causes of poverty in the personal characteristics and circumstances of individuals and households (Devereux and McGregor 2014), overlooking the structural dimensions of poverty (Calnitsky 2018; du Toit 2005). Concerns about cash transfers as handouts creating dependency are often associated with elite perceptions of poverty, with the ‘undeserving’ poor considered to be lazy and immoral (Kalebe-Nyamongo and Marquette 2014). However, resistance to ‘just giving money to the poor’ can also come from the potential beneficiaries of such schemes. In South Africa, many of the long-term unemployed poor express a preference for work programmes over cash grants on the basis that paid work brings agency and dignity, while cash may promote laziness (Fouksman 2020).

The value of integrating moral, ethical and social justice considerations into our thinking about social protection programmes has been convincingly argued (Barrientos 2013a; Devereux 2016; Hickey 2014; Ulriksen and Plagerson 2016). Yet country-level studies of social transfer targeting have remained largely focused on effectiveness, particularly minimising inclusion and exclusion errors (Handa et al. 2012; Kusumawati and Kudo 2019; Sabates-Wheeler et al. 2015; Seleka and Lekobane 2020). While such evaluations can make important contributions to improving programmes, they often overlook the vital role of public perceptions in shaping policy design. To address this gap in knowledge, this paper analyses a contested cash transfer model in Zambia through a social justice lens, contributing to our understanding of how targeting decisions are shaped by perceptions of deservingness and not (only) technical considerations.

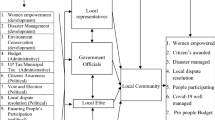

In 2003, the first cash transfer pilot in the region was launched in Zambia. The Kalomo scheme—designed by policy entrepreneur Bernd Schubert—targeted the poorest 10% of households, based on both poverty and incapacitation, identified through community targeting. This model became the focus for study tours across the region, and was later replicated in other countries including Malawi (Niño-Zarazúa et al. 2012). Since the initial pilot, Zambia has implemented six other cash transfer models with different targeting criteria. There was significant donor input into the initial policy designs through financing, pilot programmes and technical assistance (see Pruce and Hickey 2019; Ouma and Adesina 2019). This study examines the proposed ‘harmonised national targeting methodology’, known to the donor officials and government bureaucrats involved as the ‘2014’ model. The first filter for identifying the poorest households was having a high dependency ratio, defined as at least three dependents per able bodied adult or no able-bodied members at all. This targeting criterion quickly triggered widespread complaints from community members, focused on perceptions of deservingness or ‘who should get what, and why?’ (van Oorschot 2000), resulting in the re-design of the programme to increase its social and political acceptability.

This paper asks why the ‘2014’ model was rejected in communities and what the wider implications for the targeting of cash transfers might be. This case demonstrates that policy design is not a purely technical matter but is bound up with questions of deservingness and social justice, with material consequences for potential recipients of assistance. By applying van Oorschot’s (2000) criteria of deservingness to the case of cash transfers in Zambia, the paper reveals that control of circumstances is the determining criterion of deservingness among respondents. Aligning with the distinction between choice and circumstance espoused by Dworkin (2002), these findings reflect liberal notions of social justice emphasising individual responsibility rather than a relational approach that recognises the structural underpinnings of poverty and inequality.

The initial (largely donor-driven) pilot models were accompanied by impact evaluations, with the aim of building an evidence base to support Zambia’s cash transfer programme. The ‘2014’ model itself was informed by a targeting assessment, which considered the acceptability as well as the effectiveness of different targeting criteria. Models that performed extremely well in terms of poverty reduction, food security and economic multiplier effects, particularly the child grant (American Institutes for Research 2016), were found to be unpopular in communities as they were perceived to benefit better-off families while excluding many of the poorest households (Beazley and Carraro 2013). The child grant is being phased out, indicating that while the positive impact reports have helped promote the merits of cash transfers in general, they have been less influential over the design process (see also Pruce and Hickey 2019; Quarles van Ufford et al. 2016). This paper argues that popular perceptions of which groups should receive transfers need to be taken seriously in the design and analysis of targeting. It also extends our understanding of perceptions of deservingness in lower income contexts, specifically Zambia.

The paper proceeds as follows. "Deservingness and dependency: the politics of targeting" situates the politics of targeting of social protection policies in the context of long-standing social justice and deservingness debates. "Research methods" outlines the research method and data collection strategies, while "A clash of ideas: the search for a national targeting model" provides a brief overview of the case of the rejection of a centrally designed targeting model in communities in Zambia. "We are all poor here: understandings of deservingness in Zambia" analyses these events through the lens of van Oorschot’s (2000) deservingness criteria and Dworkin’s (2002) responsible liberalism. "Conclusion" draws out the theoretical and policy contributions of this study, and its relevance to social protection policies in the region.

Deservingness and Dependency: The Politics of Targeting

The strong resonances between social protection and social justice thinking are being increasingly recognised and debated within academic and policy communities (Barrientos 2016; Craig et al. 2008; Devereux and McGregor 2014; Hickey 2014; Ulriksen et al. 2015; Roelen et al. 2016). Social protection initiatives, including targeted cash transfers, engage (often implicitly) with questions of redistribution, social equality and inclusion as well as claims-making and mechanisms of entitlement (Jawad 2019). Theories of distributive justice will shape social protection responses in different ways, based on the diagnosis of injustice and the space in which it should be addressed (Hickey 2014). The technical framing of cash transfers often downplays the normative principles and (re)distributive implications of such programmes, which nonetheless tend to be shaped by liberal notions of individualism and often disregard the structural causes of poverty.

Against the background of an ongoing debate about the relative merits of universalFootnote 1 and targeted approaches to social policy (Devereux 2016; Fischer 2018; Kidd 2013), cash transfer programmes usually adopt targeting methods “to correctly and efficiently identify which households are poor and which are not” (Coady et al. 2004, p. 13). However, as Ellis (2012) points out it can be extremely difficult to differentiate the target group from other, almost as deserving, poor rural households. The process of targeting includes defining the target population and identifying the eligible population using various techniques, such as community based targeting and proxy means tests (Barrientos 2013b). This paper focuses on who is targeted based on the choice of criteria to identify eligible and ineligible households, rather than how eligible beneficiaries are identified and selected. Justified as a means of allocating scarce resources efficiently and effectively, targeting decisions are inherently political and imply differing notions of social justice determining who is deserving of assistance and on what basis. This is constructed around desert, in the philosophical sense of what someone deserves to get, needs and citizenship (Mkandawire 2005).

The categories of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor have a long history. The nineteenth century Poor Law reforms in England and the Dutch Armenwet distinguished between the ‘impotent poor’ such as the aged and sick, who were deserving of relief, and unemployed people capable of work, who were considered undeserving. These distinctions continue to have traction in contemporary welfare regimes. Based on the findings of several studies of Western Europe and the USA (Cook 1979; de Swaan 1988; Will 1993), as well as analysis of a public opinion survey in the Netherlands, van Oorschot (2000) identifies five criteria of deservingness, as follows:

-

control over neediness—the less control, the more deserving

-

need—the greater the level of need, the more deserving

-

identity—the greater the proximity to ‘us’, the more deserving

-

attitude—the more compliant and grateful, the more deserving

-

reciprocity—the more reciprocation (earning support), the more deserving

So far this heuristic has mainly been used to investigate public perceptions of deservingness in Western Europe, although it has recently been extended to consider transition countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (Gugushvili et al. 2021). In the Netherlands, “the public is very generous towards those who are not able to work… and very reserved towards those who are not willing to work (Oorschot 2000, p. 38), suggesting that control is an important criterion. Similar findings emerge in Eastern Europe and Central Asia with the highest levels of support expressed for disabled people and the lowest for unemployed people and the working poor (Gugushvili et al. 2021). However in Georgia, which has the highest solidarity index among the countries included in the study, the unemployed and working poor are perceived to be highly deserving of support. This paper will apply the framework to a lower middle-income country setting, which to my knowledge has not been done before.

Understandings of deservingness vary by country, leading to different problem framings and policy choices, so the context matters for the acceptability of different targeting models. Categorising poor people provides a basis on which to rank and prioritize them according to need or desert, implying moral judgements which in turn can justify policy decisions. The ‘deserving’ poor are not necessarily the poorest but those that attract most sympathy, including groups “usually identif[ied] as worthy of charitable assistance [such as] orphans and the disabled” (Hossain 2005, p. 966). For example, in Southern Africa governments tend to provide assistance for those who are considered labour constrained and/or ‘legitimate’ dependents, particularly the elderly and disabled (Ferguson 2015; Seekings 2009). However, elites in Malawi are reluctant to assist the ‘inactive’ poor and favour policies that support people to contribute to economic growth, such as microfinance and public works programmes (Kalebe-Nyamongo and Marquette 2014; Jimu and Misilimba 2018). Attitudes towards poor people may also vary within countries. In Bangladesh, elites prioritise those with the potential to be economically productive (Hossain 2005), while at village level there is most sympathy for households facing a sudden change of circumstances beyond their control, such as widows and abandoned wives (Matin and Hulme 2003).

Scholars investigating the political and institutional foundations of social protection have begun to unpick the social justice underpinnings of attitudes to deservingness in different settings. For example, Barrientos (2013a) has suggested that the politicisation of poverty and concomitant introduction of social assistance schemes in Latin America could be explained through Rawls’ theory of justice. A Rawlsian approach to poverty proposes that protection is provided for the worst-off on the basis of a shared agreement that a basic standard of living is ensured for all, to prevent the ‘strains of commitment’ within society from becoming excessive (Barrientos 2013a). However Dworkin, among others, has criticised Rawls for overlooking the role of individual choice and responsibility in shaping preferences, proposing that these factors should be considered within a theory of distributional justice (Craig et al. 2008, p. 5).

Dworkin (2002) distinguishes between choice and circumstance—between “what we must take responsibility for, because we chose it, and what we cannot take responsibility for because it was beyond our control” (323). For Dworkin, circumstance consists of personal and impersonal resources, including physical and mental health as well as capacity to produce goods and services, while choice refers to ambition, which includes voluntary individual choices (Wolff 2008; Dworkin 2002). This form of responsible liberalism favours social protection efforts that support self-development and external provision of financial resources within certain constraints, such as conditional cash transfers with participation requirements such as school attendance or health check-ups (Hickey 2014). However, the feasibility of drawing such a distinction has been critiqued both philosophically and morally (Scheffler 2003), as choices may be shaped by circumstances and individuals may not have adequate information about the consequences of their choices.

Radical approaches to social justice, such as Nancy Fraser’s work on redistribution and recognition, challenge structural inequalities and power relations. Fraser (1995) argues that denial of identity, recognition and status is no less harmful than being denied access to resources, and need to be addressed just as seriously. The reconfiguration of power relations requires a transformative approach that tackles social and material structures. In the context of social protection this would include universalist welfare, progressive taxation and full, decent employment. However, despite the arguments for the transformative potential of social protection to empower citizens to claim their rights (Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler 2004; Sabates-Wheeler et al., 2020), progress towards this ambitious goal remains limited (Molyneux et al. 2016).

Rather, narrow targeting tends to perpetuate individualised notions of deservingness within society based on morality and agency, which has led to the valorization of work and stigmatization of dependency in South Africa for example (Barchiesi 2007). These norms also feed into the fear of a ‘moral hazard’—tied in with narratives of self-reliance and resilience—where giving people cash will lead to laziness and welfare dependency, (Fouksman 2020; Oorschot 2000). This can influence the levels of elite and popular support for cash transfers even in high poverty contexts. An individualised approach to poverty also serves to divert attention from the limitations imposed by structural disadvantages, enabling elites to avoid taking responsibility for these factors. Nonetheless, poverty targeting remains prevalent in social protection discourse and practice, particularly in the context of cash transfers. The next sections detail and analyse how a contestation around deservingness played out in the case of social cash transfers in Zambia, demonstrating that policy design can be more directly shaped by public perceptions than technical assessments.

Research Methods

In order to gain an in-depth understanding of the responses and changes to Zambia’s cash transfer targeting criteria, a qualitative case study methodology was employed to enable detailed analysis and ‘thick’ description (Gerring 2007). Within the main case study of Zambia, three sub-case studies were selected to explore local responses to the centrally determined targeting criteria. These were Kawambwa and Mansa districts in Luapula Province as well as Petauke district in Eastern Province. The selection of these sub-cases was made purposively based on information provided by programme officials within the Ministry of Community Development and Social Welfare, who work directly with the Provincial and District officers implementing the programme. Kawambwa and Petauke districts both implemented the ‘2014’ model and experienced complaints about the targeting criteria, while Mansa implemented a less controversial model targeting people with disabilities. These sub-cases provide variation in terms of targeting experiences and geographical location. Primary data was gathered during three research visits to Zambia conducted between 2015 and 2017.

The researcher conducted 77 semi-structured key informant interviews with the stakeholders involved in the design and implementation of social cash transfers at national, provincial and district levels, some of whom were interviewed more than once. Interview participants included government representatives, both politicians and technocrats; Zambian organisations ranging from civil social organisations to think tanks and consultancies; representatives of cooperating partners, mainly the multilateral and bilateral donors engaged in the process; as well as key individuals who are currently unaffiliated. These participants were selected through purposive sampling, based on the inclusion criteria of their specific expertise with the social cash transfer programme, which was then extended through snowball sampling (Blaikie 2009). The accounts were triangulated with other interview responses, policy documents and reports, until ‘saturation’ point was reached with a high level of consistency between accounts.

In addition to the interviews, 16 focus group discussions (FGDs) were held in the sub-case districts of Kawambwa, Mansa and Petauke. The sampling of the FGD participants aimed to capture beneficiaries receiving cash transfers, non-beneficiaries who did not qualify for the transfer and Community Welfare Assistance Committee representatives who have an important role in the selection process, ensuring a gender balance and a range of ages. District Social Welfare Officers assisted with the selection of participants and were also present during the FGDs. Although this introduced a risk of bias and power dynamics, due to their role in beneficiary selection processes, it would not have been possible to access the communities without involving these gatekeepers. The FGDs were conducted in the appropriate local languages and translated by a research assistant.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Research Ethics Committee. Participation was based on informed consent and participant names were removed to protect their identity and maintain confidentiality. The participant information sheets and consent forms were translated into the relevant local languages for the FGDs.

NVivo software was used for the systematic coding during the analysis (Blaikie 2009). The FGD responses were analysed against the five deservingness criteria identified in "Deservingness and dependency: the politics of targeting" to determine the frequency of their occurrence. The FGD findings presented in "We are all poor here: understandings of deservingness in Zambia" represent the most commonly held perceptions across the different groups, with the majority of the responses corresponding to the deservingness criteria of control and need. The interview data is used to present the views of bureaucrats, donors and politicians, and to establish the similarities and differences between elite and community perceptions.

A Clash of Ideas: The Search for a National Targeting Model

In the decade following the introduction of the first cash transfer scheme in Zambia four targeting models were piloted, largely influenced by the donor agencies involved. The initial design—known as the ‘10% model’—targeted households that were both critically poor and labour constrained (the poorest 10%), while other models included a social pension and a child grant (see Table 1 for an overview of Zambia’s targeting models 2003–2017). In September 2013, UNICEF Zambia commissioned an external targeting assessment to investigate the effectiveness and acceptability of these pilot models within communities. The aim was to find a ‘harmonised’ targeting design with “national character”Footnote 2 that could replace the donor-driven pilot models and be scaled up across the country. This study found that the targeting criteria for the 10% model were in line with perceptions about the poorest households amongst communities and therefore widely accepted. On the other hand, the child grant was found to be unpopular in communities as many people believed that such targeting included better-off families while excluding some of the poorest households (Beazley and Carraro 2013). This assessment corresponds with Schüring and Gassman’s (2016) study which observes a greater preference for poverty targeting over universal categorical schemes for children and the elderly. These findings seem to contradict political economy models that suggest self-interested voters are more likely to support policies that they are able to benefit from, such as a universal child grant or pension.

Following a gradual scale up of the cash transfer programme from the single district of Kalomo in 2003 to 19 districts in 2013, there was a dramatic expansion to 50 districts in 2014 and then to 78 districts by 2016 (out of 117 districts, as of 2018Footnote 3). While the geographical roll out schedule was largely based on the poverty index, there has been some pressure to include politically strategic districts, such as the constituency of the Permanent Secretary to help secure buy-in.Footnote 4 The majority of the districts initially received either the ‘2014’ or ‘2016’ models, but the aim of finding a ‘harmonised’ model is to bring all districts in line under the same targeting criteria.

Based on the 2013 targeting assessment, the report proposed a ‘harmonised national targeting methodology’ with a double screening strategy, which became known to the donor officials and government bureaucrats involved as the ‘2014’ model. The external consultants recommended intra-household dependency as the first filter, specifying a dependency ratio of at least three dependents per able body in addition to households without able-bodied members, and a second screening consisting of a supposedly objective poverty assessment.Footnote 5 The report claimed that the dependency ratio is the best eligibility criterion for reaching the poorest, as “communities tend to consider that the poorest ones are those with no or reduced labour capacity, which is exactly what the dependency ratio captures” (Beazley and Carraro 2013, p. 75). This proposed design remained a protective form of social assistance (Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler 2004), targeting extremely poor households based on labour capacity and dependency ratio, rather than a transformative instrument (Kuss 2019).

According to the external consultants, the intention was that their proposed model would be piloted before being scaled up.Footnote 6 However, Department of Social Welfare (DSW) staff explained that there was political pressure to expand the programme quickly in order to demonstrate its capacity and potential.Footnote 7 The untested recommendations were therefore adopted directly from the report—becoming the ‘2014’ model—and the roll out started in 27 districts in January 2014. The rapid scale up meant that there was little time for capacity building and training of implementers on the selection criteria.Footnote 8 Although the report described intra-household dependency as a “simple categorical eligibility criterion” (Beazley and Carraro 2013, p. 10), it proved difficult for community volunteers and community members to understand and calculate the dependency ratio.

When the ‘2014’ model hit the ground across the country, there were widespread complaints in the districts where it was implemented, directed to Social Welfare officers, politicians and traditional leaders.Footnote 9 For example, Chieftainess Kayembo from Nchelenge district in Luapula Province claimed that “economically able families [were] lining up for the social cash transfer money when the real vulnerable were left in the cold”, (Lusaka Times 2014). The then Line Minister for Community Development and Social Welfare also received direct complaints from community members during a visit to the same Province in January 2015.Footnote 10 Concerns centred on the inclusion of those who are ‘energetic’ and ‘fit for work’ on the programme, while others—particularly the elderly—were being left out.Footnote 11 The dependency ratio meant that young, able-bodied people could qualify for the grant if they had a large number of dependents, while elderly people may not be eligible if they had an able-bodied person living with them. This rejection of the ‘2014’ model suggests that, despite acceptability in communities being “one of the main considerations”Footnote 12 according to the external consultants, the dependency ratio did not resonate with community understandings of deservingness.

A rapid assessment conducted by the department responsible for delivering cash transfers concluded that fit for work beneficiaries, such as young women with children, made the programme “politically unattractive” (Department of Social Welfare 2015). The Director of Social Welfare explained that he had learned “never [to] put younger people on the programme ahead of older people”, and that people with disabilities and older people should be the priority groups for state assistance through the SCT programme.Footnote 13 Following a targeting workshop organised by the Department of Social Welfare head office in June 2015, attended by bureaucrats, donors, civil society and external consultants, the model was changed to target only two categories of people, who also had to pass residency and affluence tests (the ‘2016’ model). These groups were those over 65 years, with proof of age through National Registration Cards; and severely disabled people, established through disability certification. While these categories were easier to administer, this change reportedly reduced the caseload of beneficiaries receiving the cash transfer in 2016 as fewer households were eligible based on the new targeting criteria.Footnote 14 Targeting discussions continued and further changes were made, resulting in the ‘2017’ model. These events demonstrate the evolving nature of Zambia’s cash transfer design in response to community perceptions and the experiences of the Social Welfare officers implementing the programme. The next section analyses this clash of ideas, engaging with van Oorschot’s (2000) welfare deservingness heuristic and Dworkin’s (2002) responsible liberalism, outlined in "Deservingness and dependency: the politics of targeting".

We Are All Poor Here: Understandings of Deservingness in Zambia

Country-level studies of cash transfer targeting have tended to focus on the effectiveness rather than the social acceptability of different targeting approaches. In the Zambia case, acceptability was reported to be “one of the main considerations”Footnote 15 during the targeting revisions in 2013, and yet a clash of ideas still emerged when the targeting model was rolled out. The UNICEF-commissioned targeting report claimed that intra-household dependency “is in line with the perception of poverty that the communities have and therefore could increase the acceptability of the targeting method” (Beazley and Carraro 2013, p. 75). However in practice, the dependency ratio was rejected in communities on the basis that households could be eligible, even if they had some level of labour capacity. Rather, it is incapacitated groups, such as the elderly and people with disabilities, that are considered by communities to be “visibly deserving”Footnote 16 in Zambia’s high poverty context.

Questions of deservingness have also surrounded Zambia’s pilot cash transfer models, with universal categorical targeting efforts largely being resisted by citizens. While the impact evaluation results from the child grant programme were particularly strong (American Institutes for Research 2016), this model has proved unpopular in communities and is, therefore, being phased out. Child grant targeting is reportedly not in line with local understandings of social justice (Institute of Development Studies 2014b, p. 72), while for the social pension, “there were outcries from communities about other categories—disabled, orphans—how do you leave them out?”Footnote 17 On the other hand, there were few complaints about the 10% inclusive model which targeted the ‘worst-off’—labour-constrained and suffering from extreme poverty (Schubert 2005)—and generally these recipients were considered to be ‘deserving’ of support by community members (Institute of Development Studies 2014a).

This focus on labour capacity echoes the categories of able-bodied male workers and their feminised dependants that have long shaped welfare states (Pateman 1989) and more recently cash transfer programmes (Ferguson 2015). According to the 2013 targeting assessment conducted by external consultants, the acceptability of selection criteria in communities is dependent on the absence of a ‘fit man’—the male breadwinner role—in the household (Beazley and Carraro 2013). However, what has emerged through the reactions to the dependency ratio enshrined in the ‘2014’ model is that in Zambia this perception encompasses any fit-for-work household member, including able-bodied women. The complaints focused on ‘young ones’, particularly women, with more than three children, although they were eligible to receive the transfer based on the dependency ratio.Footnote 18 As a senior government official reported: “if you have labour you should be working, that’s why there’s an issue with women with many children”.Footnote 19

The main reasons given by bureaucrats and donors for why younger people should not receive the transfer were as follows: younger people are assumed to be fit for work so people felt it was not fair for them to receive state assistance; and, although these younger people were eligible according to the targeting criteria, the community felt that other vulnerable households were being left out.Footnote 20 This justification fits with the focus on labour capacity, but the particular concerns about young women also brings to mind the narratives of ‘welfare queens’ and ‘cash transfer mothers’ that stigmatise women, and specifically lone mothers (Cassiman 2007; Hochfeld and Plagerson 2011; Lowe 2008). Despite female-headed households being recognised as amongst the poorest and most vulnerable in documentation, including Zambia’s Seventh National Development Plan (GRZ 2017), these responses suggest that able-bodied women are considered undeserving of state assistance in communities.

During key informant interviews with Department of Social Welfare bureaucrats at national, provincial and district levels, the elderly, people with disabilities and orphans were consistently identified as priority categories.Footnote 21 The responses from a series of community-based focus group discussions (FGDs) during the study confirmed that old age, disability and sickness were also considered by citizens to be the highest priorities for state assistance. These groups are also easy to identify, while targeting methods such as the dependency ratio may create opportunities for discretion and manipulation. The ordering of categories identified in this study broadly corresponds to the hierarchy of deservingness in Western welfare states, particularly liberal regimes such as the UK and the US. In these contexts, the public is most in favour of support for old people, followed by the sick and disabled, and then needy families with children and unemployed (van Oorschot 2000). Analysing the FGD responses against van Oorschot’s five criteria of deservingness, the most weight was placed on control: “without the possibility of control, people cannot be held responsible and thus are seen as deserving” (van Oorschot 2000, p. 36).

In this study, incapacitation emerged as the most frequently cited factor in determining deservingness to receive the cash transfer. Households with labour capacity were perceived to be able to support themselves and their families: “if they can work there is no need of helping them”.Footnote 22 Even if these households with labour capacity also had a high dependency ratio, they were perceived to be in control of their situation: “having a lot of children is their fault, it’s something they can control”.Footnote 23 The emphasis on individual responsibility aligns with Dworkin’s argument that the state should only address problems based on circumstance and not choice, although the difficulty of detaching preferences and ambitions from circumstances shaped by structural factors remains. This approach is likely to lead to more stringent targeting (see also Hickey 2014), which is indeed demonstrated in the Zambia case. The complaints about undeserving beneficiaries have led to the narrowing of the targeting criteria to focus on incapacitated groups, specifically the elderly and disabled, and reportedly also reduced coverage of the social cash transfer programme in Zambia.

The role of need is less clear within local understandings of deservingness in Zambia. In high poverty contexts, it can either be taken for granted or difficult to identify how groups differ in this regard, particularly where everyone appears to be in need (Larsen 2008). The complaints about ‘energetic’ young people supporting many dependents being eligible for the grant suggest that in communities, control is prioritised over need in determining deservingness. It is notable that the use of the controversial proxy means test (PMT) as a poverty assessment tool has not been widely contested in Zambia. Despite a number of studies finding that proxy means testing is likely to exclude the poor (Brown et al. 2018; Kidd et al. 2017), neither government officials nor FGD respondents reported any complaints about the PMT component of the ‘2014 model’. The focus of complaints on the inclusion of able-bodied beneficiaries rather than the potential exclusion of poor households suggests that in contexts of high poverty and limited resources, control becomes the determining criterion of deservingness.

In terms of van Oorshot’s (2000) other three criteria of deservingness identity—in the sense of whether the wider community could identify with the beneficiaries—did emerge to some extent, but weakly. Several respondents referred to being in ‘the same situation’,Footnote 24 and they therefore recognised the level of suffering and need for assistance. The other two criteria—attitude, in terms of docility, gratefulness or compliance; and reciprocity, which refers to earning support—were not mentioned in any of the focus group discussions.

It is important to acknowledge that understandings of deservingness in communities are more nuanced than the simplified message of ‘young versus old’ reported by bureaucrats, reflecting priorities of deservingness rather than a clear distinction between deserving and undeserving. When asked to rank households in terms of priorities of deservingness, there was general agreement that “[able-bodied households] can get but only after everyone else”.Footnote 25 There was also recognition of varying levels of deservingness: “everyone is poor, poverty is different in different households so they should get according to priorities”,Footnote 26 and some understanding of the role of fiscal space in determining the scope of the programme: “[able-bodied households] should be considered after everyone else has taken, if the money is enough”.Footnote 27

While it was beyond the scope of this study to investigate the source of these perceptions of deservingness in Zambia, it is instructive to reflect on possible factors that may have shaped these preferences for targeting incapacitated households. For example, the introduction of the 10% model as Zambia’s first pilot—with labour constraint as a key targeting criterion—may have influenced expectations of cash transfers among policy-makers and the public, particularly as this Kalomo model was held up as an example in the region. The similarities with the hierarchy of deservingness identified in various countries across Europe and Central Asia also suggests that support for those who are unable to work—whether through age, disability or illness—is a widely held view. However it is important to note that there are also marked differences between countries, with the perspectives of Malawian elites on the ‘inactive’ poor being a case in point. The influences on these varying perceptions would be a valuable area for further research.

Regardless of the origin of these perceptions, a residual approach to social protection that pits the ‘inactive’ against the ‘active’ poor appears to discount the structural dimensions of poverty—identified as asset poverty, employment vulnerability and subjection to unequal social power relations (du Toit 2005)—as well as constraints on livelihood opportunities. In 2019, the cost of a monthly food basket for a family of five, calculated annually by Zambia’s Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection, stood at K3,062Footnote 28 for Mansa (one of the sub-case districts for this study).Footnote 29 In the same year, the average monthly earnings for the informal sector, comprising 68.6% of the employed population, were K1,597Footnote 30 (Zambia Statistics Agency and Ministry of Labour and Social Security 2019). This demonstrates that in addition to reduced chances of deriving a living from one’s own labour in recent years (Harland 2014), access to the labour market is not adequate to reproduce the wellbeing of a household in Zambia, even with ‘fit-for-work’ members. This is where theories of social justice that take these structural aspects seriously diverge from Dworkin’s approach.

While a transformative approach to social protection tends to be associated with a donor-driven agenda, there are also some home-grown efforts to pursue progressive social justice goals. Since the 1970s the Churches in Zambia, particularly the Catholic Church, have played a prominent role in tackling injustices ranging from democratic deficits to poverty and inequality (Hinfelaar 2008). Although somewhat weakened, the notions of solidarity and collective responsibility embodied in Zambia’s ideology of humanism in the post-independence era remain rhetorically resonant (Harland 2014). Perhaps these legacies may provide the foundations for a relational framing of social protection, rather than the individualised accounts of social justice that have arguably been emphasised by the market-centred residualism underpinning many poverty reduction programmes (Kabeer 2014).

Conclusion

In Zambia, cash transfers have provoked citizens to engage directly with questions of redistribution based on ideas of deservingness, rooted in contested notions of social justice. Social policies concern needs, desert and citizenship, which are social constructs depending on definitions of concepts such as ‘deserving poor’, ‘entitlement’ and ‘citizens’ rights’ (Mkandawire 2005). Although targeting is often framed as a technical debate, redistributive decisions are inherently political and subject to processes of negotiation and contestation.

Applying van Oorschot’s framework of deservingness to the case of cash transfers in Zambia, the paper finds that control (of circumstance) is the determining criterion among respondents in communities with high levels of need. Interpretations of control in this context centre on availability of labour capacity and number of children. Dworkin’s strand of liberal thinking on social justice resonates most strongly here, with its emphasis on individual ‘choice’ and responsibility. Zambia’s experience demonstrates that public perceptions can be more influential than technical assessments in shaping policy design. The paper argues that these local perceptions, therefore, need to be taken seriously in the analysis of targeting. This shift is required to extend our thinking beyond a preoccupation with ‘inclusion’ and ‘exclusion’ errors to consider the social justice implications of targeting decisions that have material consequences for potential recipients of assistance.

In addition to the theoretical contributions, there are lessons here for donors and governments engaged in social protection policy-making. The significance of acceptability in terms of deservingness can lead to trade-offs between achieving programme objectives and gaining political and popular support (see also Hickey and Bukenya 2021 on Uganda). There is also a need to pilot new models to test their acceptability in communities before scaling up, which was not done in the case of the ‘2014’ model due to political pressure to scale up quickly.

More broadly, Zambia’s experience is valuable with regards to the targeting of social protection across the region. In Zambia, lack of support for universal social pensions and child grant models led cash transfer proponents to search for an alternative way of reaching a large number of poor households. The resulting design incorporated labour capacity and dependency—apparently acceptable criteria within Zambian communities—but under-estimated the levels of resistance to ‘fit-for-work’ people receiving the transfer. In this context, narrow targeting of the ‘visibly deserving’ is more acceptable—politically and socially—but also restricted in terms of reach, and largely overlooks the structural dimensions of poverty. In other countries, such as Malawi, providing assistance only to the ‘inactive’ poor is perceived to be unfair. Understanding country-specific perceptions of deservingness and taking them seriously is, therefore, vital in programme design, as well as the analysis of social protection targeting. Without elite and popular buy-in, such schemes are likely to remain residual and prospects of becoming transformative welfare systems are limited.

Notes

In the context of social policy, ‘universalism’ usually means that a social benefit or service is available to the entire population. However, it can also refer to universal categorical targeting whereby all persons within a specific demographic population, such as those over 60 or households with children under five, are eligible with no means-testing.

Interview, Senior Social Welfare Officer, Lusaka, November 2016.

In 2011 there were 73 districts, meaning that at least 44 new districts were created during this period by the Patriotic Front government.

Interview, Social Cash Transfer Unit, Lusaka, April 2015.

Interview, external consultants, Skype, July 2017.

Interview, Social Cash Transfer unit, Department of Social Welfare, Lusaka, April 2015; interview, Senior Social Welfare Officer, Lusaka, November 2016.

Interview, Social Cash Transfer unit, Department of Social Welfare, Lusaka, April 2015; interview, external consultants, Skype, July 2017.

Interview, donor representative, April 2015; interview, former Director of Social Welfare, Lusaka, November 2016; interview, Provincial Social Welfare Officer, Mansa, March 2017.

Interview, former Director of Social Welfare, Lusaka, November 2016.

Interview, Senior Social Welfare Officer, Lusaka, November 2016; interview, District Social Welfare Officer, Petauke, April 2017.

Interview, external consultants, Skype, July 2017.

Interview, former Director of Social Welfare, Lusaka, November 2016.

Non-participant observation, Ministry of Community Development targeting workshop, Lusaka, Nov 2016.

Interview, external consultants, Skype, July 2017.

Interview, former Director of Social Welfare, Lusaka, November 2016.

Interview, Provincial Social Welfare Officer, Chipata, April 2017.

Interview, donor representative, Lusaka, April 2015; interview, Senior Social Welfare Officer, Lusaka, November 2016; interview, donor representative, Lusaka, November 2016; interview donor representative, Lusaka, December 2016.

Interview, former Director of Social Welfare, Lusaka, November 2016.

Interview, donor representative, Lusaka, April 2015; interview, Senior Social Welfare Officer, November 2016.

Interview, former Director of Social Welfare, Lusaka, November 2016; interview, Senior Social Welfare Officer, Lusaka, November 2016; interview, District Social Welfare Officer, Kawambwa, March 2017; interview, Provincial Social Welfare Officer, Mansa, March 2017.

Focus group discussion I, Mansa, March 2017.

Focus group discussion I, Kawambwa, March 2017.

Focus group discussion I Mansa, March 2017; Focus group discussion II Mansa, March 2017; Focus group discussion II Kawambwa, March 2017.

Focus group discussion II, Mansa, March 2017.

Focus group discussion I, Petauke, April 2017.

Focus group discussion II, Petauke, April 2017.

Equivalent to £138.36 at current exchange rate (August 2021).

Equivalent to £72.13 at current exchange rate (August 2021).

References

American Institutes for Research. 2016. Zambia’s Child Grant Program: 48 month impact report. Washington D.C.: American Institutes for Research.

Barchiesi, F. 2007. Wage labor and social citizenship in the making of post-apartheid South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies 42: 39–72.

Barrientos, A. 2013a. Politicising poverty in Latin America in the light of Rawls’ ‘strains of commitment’ argument for a social minimum (No. 182), Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper Series. BWPI, The University of Manchester.

Barrientos, A. 2013b. Social assistance in developing countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barrientos, A. 2016. Justice-based social assistance. Global Social Policy 16: 151–165.

Beazley, R., and L. Carraro. 2013. Assessment of the Zambia social protection expansion programme targeting mechanisms. Oxford: Oxford Policy Management.

Blaikie, N. 2009. Designing social research, 2nd ed. Polity Press: Cambridge and Medford.

Brown, C., M. Ravallion, and D. van de Walle. 2018. A poor means test? Econometric targeting in Africa. Journal of Development Economics 134: 109–124.

Calnitsky, D. 2018. Structural and individualistic theories of poverty. Sociology Compass 12: e12640.

Cassiman, S.A. 2007. Of witches, welfare queens, and the disaster named poverty: The search for a counter-narrative. Journal of Poverty 10: 51–66.

Coady, D., M.E. Grosh, and J. Hoddinott. 2004. Targeting of transfers in developing countries: Review of lessons and experience. Washington D.C: World Bank Publications.

Cook, F.L. 1979. Who should be helped?: Public support for social services. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Craig, G., T. Burchardt, and D. Gordon. 2008. Social justice and public policy: Seeking fairness in diverse societies. Bristol: Policy Press.

de Swaan, A. 1988. In care of the state: Health care, education, and welfare in Europe and the USA in the Modern Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Department of Social Welfare. 2015. Rapid assessment of SCT targeting: Lessons from North-Western and copperbelt provinces. Powerpoint presentation.

Devereux, S. 2016. Is targeting ethical? Global Social Policy 16: 166–181.

Devereux, S., and R. Sabates-Wheeler. 2004. Transformative social protection. IDS Working Paper No. 232. Institute of Development Studies: Brighton.

Devereux, S., and J.A. McGregor. 2014. Transforming social protection: Human wellbeing and social justice. The European Journal of Development Research 26: 296–310.

Devereux, S., E. Masset, R. Sabates-Wheeler, M. Samson, A.-M. Rivas, and D. te Lintelo. 2017. The targeting effectiveness of social transfers. Journal of Development Effectiveness 9: 162–211.

Dworkin, R. 2002. Sovereign virtue: The theory and practice of equality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

du Toit, A. 2005. Chronic and structural poverty in South Africa: Challenges for action and research (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1753656). Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY

Ellis, F. 2012. ‘We are all poor here’: Economic difference, social divisiveness and targeting cash transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Development Studies 48: 201–214.

Ferguson, J. 2015. Give a man a fish: Reflections on the new politics of distribution. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Fischer, A.M. 2018. Poverty as ideology: Rescuing social justice from global development agendas. London: Zed Books Ltd.

Fouksman, E. 2020. The moral economy of work: Demanding jobs and deserving money in South Africa. Economy and Society 49: 287–311.

Gerring, J. 2007. Case study research: Principles and practices. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Grosh, M., C. del Ninno, E. Tesliuc, and A. Ouerghi. 2008. For protection and promotion: The design and implementation of effective safety nets. Washington D.C: World Bank.

GRZ. 2017. Seventh national development plan 2017–2021. Lusaka: Government of the Republic of Zambia.

Gugushvili, D., M. Lukac, and W. van Oorschot. 2021. Perceived welfare deservingness of needy people in transition countries: Comparative evidence from the Life in Transition Survey 2016. Global Social Policy 21 (2): 234–257.

Handa, S., C. Huang, N. Hypher, C. Teixeira, F.V. Soares, and B. Davis. 2012. Targeting effectiveness of social cash transfer programmes in three African countries. Journal of Development Effectiveness 4 (1): 78–108.

Harland, C. 2014. Can the expansion of social protection bring about social transformation in African Countries? The case of Zambia. The European Journal of Development Research 26 (3): 370–386.

Hickey, S. 2014. Relocating social protection within a radical project of social justice. The European Journal of Development Research 26: 322–337.

Hickey, S., and B. Bukenya. 2021. The politics of promoting social cash transfers in Uganda: The potential and pitfalls of “thinking and working politically.” Development Policy Review 39: O1–O20.

Hinfelaar, M. 2008. Legitimizing powers: The political role of the Roman Catholic Church. In One Zambia, many histories: Towards a history of post-colonial Zambia, ed. J.-B. Gewald, M. Hinfelaar, and G. Macola, 1972–1991. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Hochfeld, T., and S. Plagerson. 2011. The social construction of the cash transfer mother in Soweto, South Africa: the emergence of social stigma? Paper prepared for international conference on 'Social Protection for Social Justice', Institute of Development Studies, 13–15 April 2011.

Hossain, N. 2005. Productivity and virtue: Elite categories of the poor in Bangladesh. World Development 33 (6): 965–977.

Institute of Development Studies. 2014a. The wider impacts of social protection: Report on the 10% inclusive model: Kalomo, Monze and Choma. IDS: Brighton.

Institute of Development Studies. 2014b. The wider impacts of social protection: Child grant studies findings: rounds 1 and 2. IDS: Brighton.

Jawad, R. 2019. A new era for social protection analysis in LMICs? A critical social policy perspective from the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA). World Development 123.

Jimu, I.M., and G. Misilimba. 2018. Targeting practices and biases in social cash transfers: Experiences in rural Malawi. Africa Development 43 (2): 65–84.

Kabeer, N. 2014. The politics and practicalities of universalism: Towards a citizen-centred perspective on social protection. The European Journal of Development Research 26: 338–354.

Kalebe-Nyamongo, C., and H. Marquette. 2014. Elite attitudes towards cash transfers and the poor in Malawi. Birmingham: Developmental Leadership Program.

Kidd, S., 2013. Rethinking “Targeting” in international development. Development Pathways: Banbury.

Kidd, S., B. Gelders, and D. Bailey-Athias. 2017. Exclusion by design: an assessment of the effectiveness of the proxy means test poverty targeting mechanism (ILO Working Paper). Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Kuss, M.K. 2019. Implementing social protection in rural Zambia: Why transformative expectations remain unfulfilled, [conference presentation]. Development Studies Association 2019 conference, Open University, Milton Keynes, 19–21 June 2019.

Kusumawati, A.S., and T. Kudo. 2019. The effectiveness of targeting social transfer programs in Indonesia. The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning 3 (3): 282–297.

Larsen, C.A. 2008. The institutional logic of welfare attitudes: How welfare regimes influence public support. Comparative Political Studies 41 (2): 145–168.

Lowe, S.T. 2008. It’s all one big circle: Welfare discourse and the everyday lives of urban adolescents special issue: Beyond the numbers: How the lived experiences of women challenge the success of welfare reform. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 35: 173–194.

Lusaka Times. 2014. Economically able people hijack the social cash transfer programme meant for the poor. https://www.lusakatimes.com/2014/12/04/economically-able-people-hijack-social-cash-transfer-programme-meant-poor/. Accessed 28.11.2017

Matin, I., and D. Hulme. 2003. Programs for the poorest: Learning from the IGVGD Program in Bangladesh. World Development 31 (3): 647–665.

Mkandawire, T. 2005. Targeting and universalism in poverty reduction, social policy development programme paper number 23. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

Molyneux, M., W.N. Jones, and F. Samuels. 2016. Can cash transfer programmes have ‘transformative’ effects? Journal of Development Studies 52 (8): 1087–1098.

Niño-Zarazúa, M., A. Barrientos, S. Hickey, and D. Hulme. 2012. Social protection in sub-Saharan Africa: Getting the politics right. World Development 40 (1): 163–176.

Ouma, M., and J. Adésínà. 2019. Solutions, exclusion and influence: Exploring power relations in the adoption of social protection policies in Kenya. Critical Social Policy 39 (3): 376–395.

Pateman, C. 1989. The disorder of women: Democracy. Cambridge: Feminism and Political Theory, Polity Press.

Pruce, K., and S. Hickey. 2019. The politics of promoting social cash transfers in Zambia. In The politics of social protection in Eastern and Southern Africa, ed. S. Hickey, T. Lavers, M. Niño-Zarazúa, and J. Seekings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quarles van Ufford, P., C. Harland, S. Michelo, G. Tembo, K. Toole, and D. Wood. 2016. The role of impact evaluation in the evolution of Zambia’s cash transfer. In From evidence to action: The story of cash transfers and impact evaluation in Sub Saharan Africa, ed. B. Davis, S. Handa, N. Hypher, N. Winder Rossi, P. Winters, and J. Yablonski. Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York.

Roelen, K., R. Sabates-Wheeler, and S. Devereux. 2016. Social protection, inequality and social justice, World Science Report 2016. ISSC, IDS and UNESCO.

Sabates-Wheeler, R., A. Hurrell, and S. Devereux. 2015. Targeting social transfer programmes: Comparing design and implementation errors across alternative mechanisms. Journal of International Development 27 (8): 1521–1545.

Sabates-Wheeler, R., N. Wilmink, A-G. Abdulai, R. de Groot and T. Spadafora. 2020. Linking Social Rights to Active Citizenship for the Most Vulnerable: the Role of Rights and Accountability in the ‘Making’ and ‘Shaping’ of Social Protection. The European Journal of Development Research 32(1) 129–151.

Scheffler, S. 2003. What is egalitarianism? Philosophy and Public Affairs 31 (1): 5–39.

Schubert, B. 2005. The pilot social cash transfer scheme Kalomo District - Zambia (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1753690). Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY.

Schüring, E., and F. Gassman. 2016. The political economy of targeting—A critical review. Development Policy Review 34 (6): 809–829.

Seekings, J., 2009. Deserving individuals and groups: The post-apartheid state’s justification of the shape of South Africa’s system of social assistance. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 68, 28–52.

Seleka, T.B., and K.R. Lekobane. 2020. Targeting effectiveness of social transfer programs in Botswana: Means-tested versus categorical and self-selected instruments. Social Development Issues 42(1).

Ulriksen, M.S., and S. Plagerson. 2016. The principles and practice of social protection. Global Social Policy 16: 127–131.

Ulriksen, M.S., S. Plagerson, and T. Hochfeld. 2015. Social protection and justice: Poverty, redistribution, dignity. In Distributive justice debates in political and social thought: Perspectives on finding a fair share, ed. C. Boisen and M.C. Murray. Oxford: Routledge.

van Oorschot, W. 2000. Who should get what, and why? On deservingness criteria and the conditionality of solidarity among the public. Policy and Politics 28 (1): 33–48.

van Oorschot, W. 2006. Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy 16 (1): 23–42.

van Oorschot, W., F. Roosma, B. Meuleman, and T. Reeskens. 2017. The social legitimacy of targeted welfare: Attitudes to welfare deservingness. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Will, J.A. 1993. The dimensions of poverty: Public perceptions of the deserving poor. Social Science Research 22 (3): 312–332.

Woolf, J. 2008. Social justice and public policy: A view from political philosophy. In Social justice and public policy: Seeking fairness in diverse societies, ed. G. Craig, T. Burchardt, and D. Gordon. Bristol: Policy Press.

Zambia Statistics Agency and Ministry of Labour and Social Security. 2019. 2019 Labour Force Survey Report. Lusaka: Zambia Statistics Agency and MLSS.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number 1501070], as well as the Effective States and Inclusive Development research centre based at the University of Manchester. The research was undertaken at the University of Manchester, and the open access was supported by the University of Birmingham's College of Social Sciences. The author would like to thank Sam Hickey, David Hulme, Tom Lavers, Armando Barrientos, Pritish Behuria and Erla Thrandardottir for their invaluable input on earlier iterations of the paper, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that strengthened the final version. The paper was also improved through feedback received from members of the Global Development Institute state-society relations research group at the University of Manchester in 2020 and attendees at the International Political Science Association World Congress 2021. Any errors or omissions are the author’s responsibility.

Funding

Funding was provided by Economic and Social Research Council (1501070) and Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pruce, K. The Politics of Who Gets What and Why: Learning from the Targeting of Social Cash Transfers in Zambia. Eur J Dev Res 35, 820–839 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-022-00540-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-022-00540-2