Abstract

We examine the impact of tariff and non-tariff reductions on firm-level gross value of output (GVO) and productivity for various types of Indian manufacturing MSMEs for the 2002–2007 period. We merge the 3rd (2001–2002) and 4th (2006–2007) All India Census data on Indian MSMEs to create a novel dataset that includes micro-enterprises and to calculate input and final goods tariffs, ERPs and NTBs for broad product groups using information from India’s export–import policy, 1997–2003 and 2004–2009. After controlling for firm, industry, state and time-specific factors, we find tariff reductions have improved firm-level GVO and productivity for MSMEs which are technologically upgraded and quality certified. Further, the effects of input tariff reduction exceed those from final goods tariff reductions, i.e., the input sourcing channel is stronger than the final product competition channel. Liberalization of non-tariff barriers is found to have a positive effect on both GVO and productivity growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

There is, however, variation across countries in defining MSMEs. Countries define MSMEs in terms of assets, turnover or employment.

Annual Report—Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, 2016–2017: http://msme.gov.in/sites/default/files/MSME%20ANNUAL%20REPORT%202016-17%20ENGLISH.pdf.

The simple and weighted average applied MFN tariffs stood at 13% and 6.9%, respectively, in 2014–2015. See Singh (2017), Table 4, p. 14 and Table 5, p. 15.

See Press Information Bureau Government of India, Ministry of Commerce & Industry,

http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=118222 for discussion on removal of the last 20 items from the MSME list.

The Export–Import or Exim Policy consists of guidelines and instructions established by the Director General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) on matters related to the import and export of goods in India. The Foreign Trade Policy of India is guided by the EXIM Policy and is regulated by the Foreign Trade Development and Regulation Act, 1992. See http://www.exim-policy.com/.

Definition of sick SSI (small-scale industry) unit: An SSI unit should be considered 'sick' if any of the borrowal accounts of the unit remains substandard for more than 6 months, i.e. principal or interest, in respect of any of its borrowal accounts has remained overdue for a period exceeding 1 year. See https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=543&Mode=0 for further details.

The process for merging the two rounds of census data is explained in “Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics” and illustrated in Appendix A.

This merged dataset has several advantages over other firm-level databases in India for analyzing the impact of trade liberalization. Other datasets like the CMIE (Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd.) Prowess and ASI (Annual Survey of Industries) database have a very low representation of MSME firms and do not contain firm-level features such as quality standards and technological knowhow. This dataset covers registered enterprises unlike the NSSO (National Sample Survey Office) database which covers unorganized firms. None of these other datasets provide wide coverage of micro-enterprises. The Census dataset also enables a more disaggregated industry-level analysis as it contains a wide range of industries.

It is important to note that no previous studies which have examined the performance of Indian MSME firms have used both the 3rd and 4th censuses to examine the impact of trade liberalization. Coad and Tamvada’s (2012) examination was based only on the 3rd Census.

“Planning of Fourth All India Census of Micro-, Small and Medium Enterprises 2006-07 coincided with a significant development in evolution of small sector, i.e. enactment of MSMED Act in 2006, which broadened the scope of sector to include all the non-agricultural enterprises including medium enterprises falling within the stipulated investment limits. Hence, the frame for the 4th Census of registered enterprises was enlarged to include enterprises registered with KVIC/KVIB, Coir Board and under Section 2 m(i) & 2 m(i) of the Factories Act apart from the enterprises permanently registered with District Industries Centers (DICs), as against the 3rd Census, which included in its frame only permanently registered enterprises with DICs. Thus, in the 4th Census, all the enterprises permanently registered up to 31 March 2007 at District Industries Centers (DICs) of the State/UT Directorate of Industries numbering 21.04 lakh were surveyed on a complete enumeration basis. In addition, 2.15 lakh enterprises registered under Section 2 m (i) & 2 m(ii) of the Factories Act were also surveyed on a complete enumeration basis so that enterprises with investments in Plant & Machinery above Rs. one crore (which was the investment limit for SSI sector prior to the MSMED Act, 2006) were culled for inclusion in the 4th Census results of the MSME sector. Further, 0.73 lakh KVIC/KVIB units and 0.09 lakh Coir units were also taken up in the census of registered MSMEs. In all a set of 24.01 lakh enterprises were surveyed on a complete enumeration basis.

Of the 24.01 lakh enterprises surveyed on a complete enumeration basis, as mentioned above, 22.48 lakh enterprises were found relevant to the MSME sector. Enterprises which exceeded the investment limit of the medium sector under the MSMED Act (i.e. Rs10 crore) were excluded from the list of enterprises registered under Section 2 m(i) and 2 m(ii) of the Factories Act in the final results of the 4th Census. Similarly, enterprises which had more than one registration (i.e. with DIC and with KVIB/Coir) were filtered out in the process of field survey. Break-up of 22.48 lakh enterprises having filed EM II/permanently registered with DIC is 20.62 lakh; registered under Section 2 m(i) and 2 m(ii) of the Factories Act 1948, 1.16 lakh; KVIC/KVIB/Coir units 0.70 lakh”; Final Report of 4th All India Census of MSME Registered Sector 2006–2007, Pages 9–10), This indicates that the study goes beyond the ASI dataset which mainly concentrates on large firms to give a main focus on MSME firms. Note that ‘lakh’ refers to 100,000 and ‘crore’ refers to 10 million.

A tehsil or tahsil/tahasil, also known as taluka (or taluq/taluk) or mandal, is an administrative division. It is an area with a city or town that serves as its administrative centre. It may contain additional towns and a number of villages.

See http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/Administrative_division.aspx.

The National Industrial Classification-2004 (NIC-2004) plays an important role in maintaining standards of data collection, processing and presentation as well as applications in policy formulation and policy analysis. This classification is used in all types of censuses and sample surveys conducted in India. The latest and fifth Industrial Classification, NIC-2004 was developed and released by CSO in November 2004. See http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/upload/nic_2004_index.htm.

See Appendix A, Tables 16 and 17 for a description of the variables in the 3rd and 4th All India Census of MSMEs and an illustration of the merger procedure.

Although, in both the censuses the authority had collected data for the preceding 2 years (e.g., 2000 and 2001 in the case of Census 2002, and 2005 and 2006 in the case of Census 2007), the information is limited to some key performance indicators, such as the GVO. Thus, our results are confined just to the years 2002 and 2007. But while estimating productivity using the Levinshon–Petrin (LP) method we have utilized the additional information for some major variables, such as the GVO, intermediate inputs, total assets and level of employment (2000–2002 and 2005–2007).

See MSME Annual Report (2015–2016), Table 1, pp. 7–8.

Appendix Table 18 shows the distribution of MSME firms across states.

Appendix Table 19 provides the distribution of MSMEs across industry groups. The Census report provides other descriptive statistics, including employment, output and asset distribution across industries. These broadly mirror the industry-wise distribution of MSMEs although certain industries such as textiles, chemicals and machinery and equipment feature importantly.

Appendix Table 20 shows the major reasons reported by sick or incipient sick units as per the final report on the 4th Census.

The unorganised sector is defined by the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector as “consisting of all unincorporated private enterprises owned by individuals or households engaged in the sale or production of goods and services operated on a proprietary or partnership basis and with less than ten total workers”; Report on Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganised Sector (p. 2) See http://dcmsme.gov.in/Condition_of_workers_sep_2007.pdf.

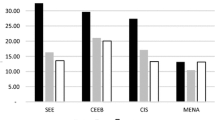

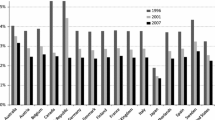

We also identify the effects of trade policy across two broad groups of MSME firms; (1) the non-food and non-agro-based industry group and (2) the food and agro-based industry group. These two industry groups are selected because of the divergent trends in tariff liberalization they have experienced during our study period. The 2004–2009 EXIM Policy which was introduced in 2004, widened the gap in tariff rates between these two groups of industries. The final goods tariff rate for the food and agro-based industry group declined only marginally from 39.89% in 2001–2002 to 35.58% in 2006–2007, while the final goods tariff for the non-food and non-agro-based industry group declined to as low as 6.57% in 2006–2007. Appendix Figures 2, 3, anc 4 provide the differential trends in tariff rates for these two industry groups. See Mukherjee and Chanda (2017) for further discussion of these differential trends. Given this divergent trend in tariff liberalization, we have conducted a robustness check in “Robustness Checks”, where we employ a difference-in-difference model to estimate the differential effect of EXIM Policy, 2004–2009 on firm-level performance of Indian MSME manufacturing across these two industry groups.

See the gross revenue approach to productivity estimation discussed in Levinsohn and Petrin (2003).

It is important to note that the LP method of productivity estimation requires last year’s input data to proxy the unobservable productivity term, as it follows Markov’s chain rule while choosing quantity of inputs in the present period. Hence, we have utilized the additional information of input variables, such as intermediate inputs, total assets and level of employment for the year 2000–2001 as a proxy for the productivity term of 2001–2002 in the 2nd stage of the LP method and similarly we have taken proxy using the data of 2001–2002 for the productivity term of 2006–2007. Thus, in LP productivity estimation results, we have utilized 3 years data of major variables. However, as pointed out earlier, this information is limited to some key performance indicators, such as GVO. Thus, our analysis is confined to the years 2002 and 2007.

It is important to note that, unlike the usual LP results of other papers, Table 5 highlights a very low co-efficient value of total input expenditure (though significant), as this segment consists of all MSME firms, which operate at a very small scale and are unable to use quality inputs to improve their productivity. Moreover, Table 5 indicates that labour and initial fixed assets are the main factors for their productivity improvement.

The productivity index is calculated as the logarithmic deviation of a firm from a reference firm's productivity in the particular industry in the base year. For the productivity index calculation, we have subtracted the productivity of a firm (mean log output and mean log input level) in 2001–2002 (base year) from the estimated firm-level TFP to get the productivity index.

However, the main results also remained robust after the inclusion of the outliers.

International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities, Revision. 3

http://unstats.un.org/unsd/cr/registry/regcst.asp?Cl=2 and National Industrial Classification,

The STAN database provides a comprehensive tool for analysing industrial performance at a relatively detailed level of activity across countries. It includes annual measures of output, labour input, investment and international trade which enable the construction of indicators pertaining to productivity growth, competitiveness and general structural change.

http://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/stanstructuralanalysisdatabase.htm.

“The World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) database provides access to international merchandise trade, tariff and non-tariff measures (NTM) data. See http://wits.worldbank.org/. The ASI is the main source of industrial statistics in India. It enables analysis of the growth, composition and structure of organised manufacturing sector across a wide range of activities.

http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/asi/ASI_main.htm?status=1&menu_id=88.

We have followed the standard definition of export propensity provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to calculate the same at the industry-level over time. See http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctab2017d6_en.pdf.

While estimating the TFP index we have taken care of the effects of firm size and total employment. Hence, we have not taken these as control variables in the fixed effect model specification.

A higher NTB index value represents a more liberalized regime. This is because, in contrast to earlier studies which construct NTB indices by giving a value of 0 for freely imported products and 1 for products prohibited from imports, we invert the scale by assigning a value of 0 for prohibited products and 1 for the freely imported products. Hence, a higher value of this index represents a more liberalized NTB regime (See Appendix Tables 24, 25, 26 and 27 for details).

See Appendix Table 23 for the results showing the absence of trade policy endogeneity with firm-level performance measures. It should be noted that Topalova and Khandelwal (2011) find trade policy endogeneity between 1997 and 2001, though not for the 1989–1996 period, indicating that there is no systematic trade policy endogeneity with the latter varying over different time periods. The absence of endogeneity between GVO and productivity on the one hand and trade policy on the other between 2002 and 2007 can be explained by the fact that there was a steady move towards trade liberalization in India with the introduction of the EXIM policy in this period, as well as the removal of NTBs that India had to undertake as part of its WTO obligations. We still ensure the robustness of our results in the presence of endogeneity by employing a DID model (see Robustness Checks).

Before examining the relationship between import tariff liberalization and firm performance for the various sub-groups of Indian MSMEs (i.e., Panels 1–4 of Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10) we undertook a post-estimation test of equality between the coefficient means of 'tariff variables' for sub-groups (i.e., all vs. modern power sourced, all vs. high quality, all vs. high tech, all vs. sick and finally with their counterparts). The results show a significant mean difference among the coefficients for each sub-group. For instance, the test for the mean coefficient differences between all MSMEs (i.e., Panel 0) and technologically advanced MSMEs (i.e., Panel 4, Column 1) gives a calculated Chi square (1) value of 10.05 (and the P value is 0.0015), which indicates that the impact of tariff liberalization on firm performance differs significantly for all MSMEs versus technologically advanced MSME firms..

We also include a size-square variable in our model to control for a possible non-linear relationship between firm-size and GVO. Our results remain consistent with the earlier ones. See Appendix D.

It would have been useful to examine the effects of input tariff liberalization on the import behavior of MSME segments (sub-groups) for the study period to identify the significance of the input channel for different groups of firms. However, such analysis could not be undertaken as the census data did not provide information on firm-level imports.

See http://dcmsme.gov.in/publications/MSMEIniciativeEnglish.pdf for further details on initiatives aimed at supporting MSME firms.

A higher NTB index value represents a more liberalized regime, as explained earlier.

The NTB index values exceeds 90 (i.e., mostly free from any import restrictions) for almost 99% of our sample observations. It is important to note that the variation in growth of firm-level GVO across various kinds of Indian manufacturing MSME firms could be better explained by calculating the NTB index at a more disaggregated level (i.e., for 4-digit industry groups). However, our construction of this index, as outlined in Appendix C, is at the 2-digit level as the purpose is to understand the broad overall trend in NTBs over our study period and to compare the results against those obtained for tariff liberalization. Disaggregated analysis of the trends in NTBs is left for future research.

While the average tariff rate in low protection industries fell from nearly 30% to a little over 11% between 2002 and 2007, in high protection industries, the average tariff rate declined only marginally from 36% to 32% (as highlighted in “Data Sources and Descriptive Statistics”).

See Chapter 13 (pp. 455–468) in Wooldridge (2013) Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th Edition for more details about the DID approach in Two-Period Panel Data Analysis framework.

For instance, MSME which belong to low-productivity industry groups may receive much higher protection in terms of higher tariff rates compared to high-productivity firms. This might lead to an omitted variable bias in the analysis.

The results for the preliminary DID model with treatment dummy (estimated using OLS) are presented in Appendix E.

It should be noted that, in the productivity equation (Eq. 7), we do not control for total fixed assets and employment as these variables have already been used in the productivity estimation.

Mukherjee and Chanda (2016) has confirmed the greater impact of NTB relative to tariff liberalization on firm-level performance for different sub-groups of the textile industry over the 1999-2009 period.

The discussion of the methodology for tariff measurement is based on Mukherjee and Chanda (2017).

Data extracted on 24 Mar 2014 10:18 UTC (GMT) from OECD. Stat, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=STAN_IO_TOT_DOM_IMP.

The discussion of the methodology for NTB measurement is based on Mukherjee and Chanda (2017).

The usual NTB index would give 0’s for import free products, hence the reverse formulation.

This is due to the fact that, in other previously constructed NTB measures, both prohibited and restricted imported items were considered to be fully protected and was assumed to have no imports happening over the years.

The size-square variable is included to control for a possible non-linear relationship between firm-size and GVO.

References

Ahsan, R.N. 2013. Input tariffs, speed of contract enforcement, and the productivity of firms in India. Journal of International Economics 90: 181–192.

Alfaro, L., and Eliza Hammel. 2007. Capital flows and capital goods. Journal of International Economics 72 (1): 128–150.

Aw, B.Y., Xiaomin Chen, and Mark J. Roberts. 2001. Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials and turnover in Taiwanese manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics 66 (1): 51–86.

Balakrishnan, P., M. Parameswaran, K. Pushpangadan, and M. Suresh Babu. 2006. Liberalization, market power, and productivity growth in Indian industry. The Journal of Policy Reform 9 (1): 55–73.

Bas, M. and A. Berthou. 2011. “The Decision to import capital goods in India: Firms’ financial factors matter.” Centre d’études prospective et d’informations internationals (CEPII), Working Paper No 2011–06.

Bernard, A., J. Eaton, J.B. Jensen, and S. Kortum. 2003. Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review 93 (4): 1268–1290.

Coad, A., and J.P. Tamvada. 2012. Firm growth and barriers to growth among small firms in India. Small Business Economics 39 (2): 383–400.

Corden, W.M. 1966. The structure of a tariff system and the effective protective rate. Journal of Political Economy 74 (3): 221–237.

Costantini, J., and M. Melitz. 2008. The dynamics of firm-level adjustment to trade liberalization. In The organization of firms in a global economy, ed. E. Helpman, D. Marin, and T. Verdier, 107–141. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Das, D. K. 2003. Quantifying trade barriers: has protection declined substantially in Indian manufacturing. Economic and Political Weekly, January 31st Issue.

Das, D.K. 2004. Manufacturing productivity under varying trade regimes, 1980–2000. Economic and Political weekly 2004: 423–433.

Das, D. 2008. Trade barriers measurement: a methodological overview. Unpublished mimeo. Manila: Economics and Research Department, Asian Development Bank.

Eaton, J., and S. Kortum. 2001. Trade in capital goods. European Economic Review 45 (7): 1195–1235.

Ethier, W.J. 1979. Internationally decreasing costs and world trade. Journal of International Economics 9: 1–24.

Ethier, W.J. 1982. National and international returns to scale in the modern theory of international trade. The American Economic Review 72 (3): 389–405.

Goh, A.-T., and Jacques Olivier. 2002. Learning by doing, trade in capital goods and growth. Journal of International Economics 56 (2): 411–444.

Goldar, B., and A. Kumari. 2003. Import liberalization and productivity growth in Indian manufacturing industries in the 1990s. The Developing Economies 41 (4): 436–460.

Goldberg, P.K., Amit Khandelwal, Nina Pavcnik, and Petia Topalova. 2010a. Multi-product firms and product turnover in the developing world: Evidence from India. Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (4): 1042–1049.

Goldberg, P.K., Amit Khandelwal, Nina Pavcnik, and Petia Topalova. 2010b. Imported intermediate inputs and domestic product growth: Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 125 (4): 1727–1767.

Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Annual Report 2016–2017, New Delhi.

Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Annual Report 2015–2016, New Delhi.

Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Annual Report 2013–2014, New Delhi.

Government of India, Ministry of Finance. 2013. Report of the Inter-Ministerial Committee for Boosting Exports from MSME Sector, New Delhi

Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Final Report on Fourth All India Census of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises 2006–2007: Registered Sector (GOI.), New Delhi.

Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Final Report on Third All India Census of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises 2001–2002: Registered Sector (GOI.), New Delhi.

Grant Thornton and FICCI. 2013. “Integrating MSMEs with the Global Value Chain”, New Delhi.

Grossman, G., and Elhanan Helpman. 1991. Innovation and growth in the global economy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gyampah, K.A., and S.S. Boye. 2001. Operations strategy in an emerging economy: The case of the Ghanaian manufacturing industry. Journal of Operations Management 19: 59–79.

Hasan, R. 2002. The impact of imported and domestic technologies on the productivity of firms: Panel data evidence from Indian manufacturing firms. Journal of Development Economics 69 (1): 23–49.

Kathuria, V. 2002. Liberalization, FDI and Productivity spillovers- an analysis of Indian manufacturing firms. Oxford Economic Papers 54 (4): 688–718.

Kathuria, V., S.R. Raj, and K. Sen. 2012. The effects of economic reforms on manufacturing dualism: Evidence from India. Journal of Comparative Economics 41 (4): 1240–1262.

Kato, A. 2009. Product market competition and productivity in the indian manufacturing industry. The Journal of Development Studies 45 (10): 1579–1593.

Key Statistics and Trends in International Trade: The Status of World Trade- united nations conference on trade and developmeT (UNCTAD) 2017. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctab2017d6_en.pdf

KPMG, “The New Wave Indian MSME: An Action Agenda for Growth”. CII, New Delhi, 2015.

Kushnir, K., Melina L. Mirmulstein, and Rita Ramalho. 2010. Micro, small and medium enterprises around the world: How many are there and what affects the count? MSME Country Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank/IFC.

Lee, J.W. 1995. Capital goods imports and long-run growth. Journal of Development Economics 48 (1): 91–110.

Levinsohn, J., and Amil Petrin. 2003. Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. The Review of Economic Studies 70 (2): 317–341.

Loecker, J.D. 2011. Product differentiation, multi-product firms and estimating the impact of trade liberalization on productivity. Econometrica 79 (5): 1407–1451.

Loecker, J.D., P.K. Goldberg, A.K. Khandelwal, and N. Pavcnik. 2016. Prices, markups, and trade reform. Econometrica 84 (2): 445–510.

Martin, L.A., S. Nataraj, and A.E. Harrison. 2017. In with the big, out with the small: Removing small-scale reservations in India. The American Economic Review 107 (2): 354–386.

Mallick, S., and H. Marques. 2008. Passthrough of exchange rate and tariffs into import prices of India: Currency depreciation versus import liberalization. Review of International Economics 16 (4): 765–782.

Melitz, M.J. 2003. The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71 (6): 1695–1725.

Mukherjee, S., and R. Chanda. 2017. Differential effects of trade openness on Indian manufacturing firms. Economic Modelling 61: 273–292.

Mukherjee, S., and R. Chanda. 2016. Impact of trade liberalization on indian textile firms: A panel analysis. International Trade and International Finance 2016: 229–255.

Nataraj, S. 2011. The impact of trade liberalization on productivity: Evidence from India’s formal and informal manufacturing sectors. Journal of International Economics 85: 292–301.

Parameswaran, M. 2010. International trade and R&D investment: Evidence from manufacturing firms in India. International Journal of Technology and Globalisation 5 (1): 43–60.

Pandey, M. 1999. NCAER report on trade protection in India. New Delhi: National Council of Applied Economic Research.

Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Commerce & Industry. 2015, “De-reservation of remaining 20 items reserved for Micro and Small Enterprises Sector”, April 13. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=118222.

Rivera-Batiz, L., and Paul Romer. 1991. Economic integration and endogenous growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (2): 531–555.

Singh, H.V. 2017. “Trade Policy Reform in India since 1991”. Working Paper 02. Brookings India. New Delhi. March.

Singh, R.K., Suresh K. Garg, and S.G. Deshmukh. 2010a. Strategy development by small scale industries in India. Industrial Management & Data Systems 110 (7): 1073–1093.

Singh, R.K., Suresh K. Garg, and S.G. Deshmukh. 2010b. The competitiveness of SMEs in a globalized economy: Observations from China and India. Management Research Review 33 (1): 54–65.

Sivadasan, J. 2009. Barriers to competition and productivity: Evidence from India. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2161.

Topalova, P., and Amit Khandelwal. 2011. Trade liberalization and firm productivity: The case of India. Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (3): 995–1009.

Wooldridge, J. 2013. Introductory econometrics: A modern approach, 5th ed, 455–468. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Xu, B., and J. Wang. 1999. Capital goods trade and R&D spillovers in the OECD. Canadian Journal of Economics 32 (5): 1258–1274.

Other Important Links and Databases

https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Id=543&Mode=0/.

https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=wcontact&page=prowess.

http://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/Administrative_division.aspx.

http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/asi/ASI_main.htm?status=1&menu_id=88.

http://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/stanstructuralanalysisdatabase.htm.

http://wits.worldbank.org/WITS/WITS/Default-A.aspx?Page=Default/.

http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=STAN_IO_TOT_DOM_IMP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Methodology for Merging of 3rd and 4th Census Data for Registered MSME Firms

See Tables 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Appendix B

Tariff Measures: Final Goods, Inputs and Effective Rate of Protection (ERP) Footnote 50

We calculate the industry-level effective rate of protection (ERP) by following Topalova and Khandelwal (2011) to measure the net effect of tariff liberalization accounting for both final goods and input tariff reductions. The exact formulation of input tariff and ERP for the jth industry at time t, as defined by Corden (1966) is given as:

where αjs is the share of imported input s used in the value of output j.

The above calculation is done for all the 2-digit industry groups (NIC 2004) based on the industry-level final goods tariff (average MFN rate) data collected from the WITS database and the Input–Output data collected from the Input–Output Table (2004–2005) of the OECD-STAN database.Footnote 51

From the Input–Output table, we calculate the share of each sth imported input used in the value of output for the jth industry at the 2-digit industry groups (NIC 2004). Then, by using Eq. (10), we have calculated the input tariff for each 2-digit industry group over the 1999–2009 period. After calculating the input tariffs, we also calculate their ERP by using the formulation given in Eq. (11). See Tables 21, 22, and 23 and Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Source Mukherjee and Chanda (2017)

Trends in final goods tariff for different industries

Source Mukherjee and Chanda (2017)

Trends in input tariff for different industries

Source Mukherjee and Chanda (2017)

Trends in effective rate of protection for different industries

Appendix C

Measurement of Non-tariff Barriers (NTB) Footnote 52

Non-tariff barriers (NTB) have assumed a lot of importance in India in the last two decades with the decline in tariff protection. Thus, it becomes important to use tariffs as well as NTBs to measure trade protection in the Indian context. Although it is very hard to find a good dataset to measure NTBs, there are a few studies (Das 2003; Pandey 1999) which have attempted to measure NTBs for the period 1980–2000, using the import coverage ratio. This measurement of NTB captures the relative restrictiveness of imports for different industries. The import coverage ratios are defined as the percentage of a product’s imports within a category that are affected by an NTB. The formulation of the NTB coverage ratio is given as follows:

Define wi= mi/∑mi as the import weight, where mi= imports of the ith commodity where ∑mi is the total imports.

Then, the NTB coverage ratio is defined as ∑niwi. An alternative is to calculate simple averages for the coverage ratios.

The coverage ratio for each input–output sector has been calculated according to the following weighting scheme for each 8-digit tariff line and has been assigned a number:

-

0% if no NTB applies to the tariff line (i.e., if no licensing is required)

-

50% if imports are subject to special import licenses (SIL)

-

100% if imports are otherwise restricted or prohibited.

In our study, we use a similar idea but the construction of the variable differs. As the main objective is to examine the impact of the reduction in NTBs for various industries (both partial as well as full) on firm performance, instead of constructing the NTB coverage ratio, we have taken an inverted version of the NTB measure by reversing the weighting scheme for each 8-digit tariff line used by Pandey (1999) and Das (2003).Footnote 53 This is mainly done to capture both the effects of partial and full liberalization policies across industries for the period 1999–2009. We use the following weighting scheme for each 8-digit tariff line:

-

100% if no NTB applies to the tariff line (i.e. if no licensing is required) (ni = 1)

-

50% if imports are restricted by different import licensing policies (ni = 0.5)

-

0% if imports are fully prohibited only (ni = 0)

Then, the Industry-level Inverted NTB coverage ratio is defined as,

where, j stands for a particular 2-digit industry and i represents a product line within that particular industry, wi = mi/∑mi as the import weight, and where mi = imports of the ith 8 digit level commodity where ∑mi is the total import of the jth industry.

This above scheme has enabled us to take into account the effects of those imported items (8-digit HS commodities) whose imports are either free or partially free. This is a value addition to the other previously constructed NTB measures, which do not take into account the effects of those imported items, whose imports are partially restricted.Footnote 54

Based on the above weighting scheme, we have firstly assigned an appropriate value to each 8-digit product for every year from 1999 to 2009. We have next also calculated their import share at the 2-digit industry-level for each of the years. Then, we have applied these values to Eq. (12) to get the NTB index for the entire 2-digit industry as classified by the HS system and NIC 2004 (ISIC revision 3) for the study period 1999–2009.

We have collected the data for import conditions (import policy) for each 8-digit product for the period 1999–2009 from the DGFT, Government of India.Footnote 55 The import data for each 2- and 8-digit industry for the period 199–2009 has been collected from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Department of Commerce, Government of India.

See Tables 24, 25, 26, 27 and Fig. 5.

Appendix D

Relationship between GVO and Tariff barriers with a size-square variable Footnote 56

Appendix E

Analysis of Preliminary DID model (OLS) with Treatment Dummy

See Table 32.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mukherjee, S., Chanda, R. Trade Liberalization and Indian Manufacturing MSMEs: Role of Firm Characteristics and Channel of Liberalization. Eur J Dev Res 31, 984–1062 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-0196-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-019-0196-1