Abstract

Rooted in a Durkheimian functionalist reading of religion, in this article, we present and discuss the results of a scoping study of on-line sources on the delivery of spiritual care during the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Spiritual care highlights the bond between healthcare and religion/spirituality, particularly within the growing paradigm of holistic and humane care. Spiritual care is also an area where the importance of the physical presence of receivers and providers is exceptionally important, as a classic anthropological understanding of the religious ritual would maintain. Three themes were found, which speak to changes brought about by the pandemic. These revolve around disembodiment, solitude, and technology in spiritual care, of religious and non-religious nature. A fourth theme encapsulates the ambivalence in the experience of spiritual care delivery, whereby distant and virtual care could only partially compensate for the impossibility of physical presence. On the one hand, we draw from anthropology of the ritual and phenomenology to make the case for the inalienability of intercorporeality in being there for the other. On the other hand, relying on digital religious studies and post-human theories, we argue for an opening up to new ways of conceptualising the body, being there, and being human.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The longing for immortality of the Pharaoh Sneferu, captured by his nose-to-nose exchange of breath with Sekhmet, the Lion Goddess (Martin 2010, p. 16) is a mythical representation of a bodily connection between finite and infinite, via the breath, or spirito. This mythical scene is taken as an emblem of spiritual care, which is an exceptionally good area to capture how healthcare and spirituality/religion are together bound to the body and to the fleshly presence of both receivers and providers. This mythical scene is also a potent visual reference to grasp the magnitude of how the COVID-19 health disaster changed the spiritual care encounter, precisely in relation to the role of the body and the nature of being there. This article is rooted in a scoping study of on-line sources on the delivery of spiritual care to hospital patients, their relatives, and frontline healthcare professionals during the first peak of the pandemic in England. The aim of the scoping study was to explore how spiritual care was described by the media, and in the websites of NHS Trusts and religious and non-religious organisations. This article presents, reflects upon and theorises on the results of the scoping study of on-line sources. The title of this article evokes what we have found. Ritual modifications to prevent body contact (which involved, for example, the use of earbuds, instead of the priest finger, during the anointment sacrament), the growth of solitary and creative practices to establish spiritual proximity with the distant loved ones (such as listening to music), and the unprecedented massive use of technologies (in particular mobile phones and tablets to virtually connect with spiritual care providers), indicated that disembodiment, solitude and technology were three key changes in spiritual care, of religious and non-religious nature. The fast-growing corpus of studies (Carey 2021) on spirituality and spiritual care during COVID-19 resonates with the results of our study. Such revitalised interest in the topic reminds us of that ‘intimate link’ (del Castillo 2020) between spirituality and healthcare, to the point that a blending of the ‘seemingly divergent view of science, religion, and government’ has been advocated (Hong and Handal 2020, p. 2266). Religious and spiritual private practices, search for and demand of spirituality resources, hot-lines, conference calls and tele-chaplaincy have considerably increased during the pandemic (Papadopoulos et al. 2020, 2021a; Ribeiro et al. 2020; Taylor 2020); this invariably speaks to a global need for spiritual comfort in a moment of existential crisis.

There is not a universally or uncritically accepted understanding of religion. In the following sub-section of this introduction, we choose to frame the growing turn to spirituality and religiosity registered during the pandemic with a functionalist model of religion. A functionalist read of religion maintains that religions and their rituals play an important role in society, inasmuch as they promote accepted and pro-social behaviours, they emphasise social order and cohesion as well as transgenerational continuity of values, while also helping members of society feel connected with a higher dimension and sense-making (Durkheim 2008). We particularly value this last element to maintain that Durkheim theorising appropriately supports an understanding of the increased need to connect to a transcendent and sacred dimension in COVID-19 times. This phenomenon in turn corroborates critiques of a secularisation argument. But not only. Durkheim’s model helps us posit the importance of the body in spiritual care, where there is a simultaneous relation to religion/spirituality and health/care. In the second sub-section of this introduction, we expand on the increased inclusion of spiritual care in mainstream healthcare, which started before the recent global health disaster. We argue that the enhanced importance of spiritual care sits within the growing paradigm of holistic and humane care—which further seems to speak to a rapprochement between religion/spirituality and the scientific/secular, or at least to the inadequacy of a rigid separation between the two (Turner 2014). After the introduction, we present the scoping study of on-line sources, first the methods, followed by the results. In the last discussion section, we address the changes in spiritual care that our study’s results speak to together with the mixed experiences in relation to virtual and at-distance spiritual care, whereby both its usefulness and its limits have emerged from the study sources. On the one hand, relying on classic anthropological readings of the religious ritual (i.e., Van Gennep, Tambiah, and Turner), as well as on Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty phenomenology, we maintain the inalienability of intercorporeality in that being there for the other. This becomes apparent in care—and exceptionally in spiritual care that aims to join the physical with the metaphysical. The Durkheimian model is here connected to and corroborated by these phenomenological readings of the inalienability of the bodily presence that crucially rests in spiritual care. On the wake of pivotal theories around forms of embodiment within the French school—from Mauss’ ‘techniques of the body’ (Mauss 1973) to Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’ (Bourdieu 1977, 1984), and from Foucault’s ‘biopower’ and ‘technologies of the self’ (Foucault et al. 1988, 2010) to Merleau-Ponty ‘intercorporeality’ (Merleau-Ponty 2013)—there has been growing attention to the body and its relationship to religion specifically (Csordas 1993; Turner 2008). This article contributes to the growing corpus of phenomenological reflections around embodiment, intercorporeality and being there during the pandemic (Carel et al. 2020; Yoeli 2021).

On the other hand, digital religion studies and Anthropocenic and post-human theories (Braidotti 2013) —which are both paired by the immense progress in advanced technologies in health and social care—invite opening up to new ways of conceptualising the body as a fundamental existential dimension of being there and being human in the spiritual/religious encounter. Digital religion studies offer important insights whereby the role of the bodily presence is revisited, and a metaphysical dimension of spiritual quest can well integrated with digital means. Proliferating post-human theories differently describe and make sense of the current era where the human—as the normative category of most noble species at the centre of the world—is being decentred, relativised, and re-conceived (Braidotti 2019). In post-human theorising, both humanism and anthropocentrism are criticised. The post-human turn is rooted in the dissolution of the distinction between nature and culture, and look at ‘human-non-human linkages’ and hybridisation—with the environment (Tsing 2015), other species (Haraway 2003) and advanced technologies too (Bono et al. 2008; Haraway 2006). Further research is needed to explore, via the ‘post-human figuration’ (Braidotti 2019), these unknow territories, and the possibilities of a ‘blended being’, or new conceptualisations of ‘being human’, within that ethical dimension of caring for the other and connecting with the mystery of life in new post-human, cyber-ontocosmologies.

The function of spirituality and religiosity in COVID times

Other concepts, as the Latin spirito, revolve around the idea of the breath/spirit as what connecting the caducous with the perennial, such as the Hindu prana, Chinese qi, Greek pneuma, and Jews ruach. Spirituality is associated to a presence that helps us feel connected with something transcending us—with a metaphysical dimension going beyond what is tangible and transient. This dimension is sometimes referred to as sacred, in theistic and nontheistic terms, and can pertain to an ample array of objects, places, and people (Durkheim 2008; Pargament and Mahoney 2009). Spirituality is also a dimension connected to religiosity as well as to beliefs, cults, and religious rituals. Commonly, it is more associated with personal beliefs and experiences, whereas religion and religiosity imply the presence of a group, social practices, doctrines, institutions, and well-defined divine figures (Hill et al. 2000; Koss-Chioino and Hefner 2006). Spirituality and religiosity, however, overlap, merge, coexist or are kept separated, within a religious tradition, a group of followers or even within an individual. Spirituality sits at the centre of most religious traditions and practices, it is intrinsically intra-faith and can both encompass and transcend religion, standing as a meaningful dimension in itself (Ellison and Levin 1998).

In this article, we address spirituality within the framework of spiritual care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The article is rooted into four interrelated aspects of Durkheim’s (Épinal 1858—Paris 1917) legacy in relation to religion: (1) social cohesion; (2) meaning-making; (3) health; (4) rituals. During the pandemic, an increased need for and manifestations of religiosity, spirituality and spiritual care have been registered (Papadopoulos et al. 2020, 2021a; Ribeiro et al. 2020; Taylor 2020). The first two aspects of social cohesion and meaning-making assist us in reading this phenomenon as a quest for spiritual comfort in reaction to one of the greatest threats to social cohesion and existential meaning humanity has faced—as a consequence of the massive reduction in social interaction coupled with the a massive number of deaths. In this sense, COVID-19 has arguably corroborated a functionalist read of religion, while also re-affirming the inalienable religious dimension of every society, as the late Durkheim also maintained (Durkheim 2008). Growing research in spirituality (Jupp 2009; Wood 2010) fuels criticism of the classic secularisation theses, including the Durkheimian one (Durkheim 2013). The third aspect of health in the Durkheimian legacy, as synthetised for the sake of this article’s premise, helps explaining the increasingly recognised role of spirituality/religion in health and healthcare, on which we expand below. Religiosity and spirituality have been shown to increase positive health. Accordingly, the connection between social capital and inequalities in health and illness is established in public health, and the root of this connection in Durkheim’s sociology has been also emphasised (Pescosolido and Georgianna 1989; Schneider-Kamp 2021; Turner 2003). Finally, in Durkheim’s thought, the importance of an embodied dimension of religious lies in the key function played in it by rituals and ceremonies. In rites, the bodily experiences of ‘collective effervescence’ (Durkheim 2008), and other somatic transformations and performances, are conducive to a flesh-based sense of connection with the sacred, and the group (Mellor et al. 1997). The longing for this connection is more likely to be awaken in particular moments of people’s life, such as the exhalation of our last breaths, which are also significant for the group who is losing one of its members.

Spirituality and the re-humanisation of healthcare

Spirituality would appear as a universal concept and existential dimension (de Jager Meezenbroek et al. 2012). Nonetheless, this does not imply that it resonates with everyone, at all times. Illnesses and approaching death often are moments when people may feel the need for a spiritual carer. However, the connection between spirituality/religion and health/care is multifaceted, involving behavioural, sociocultural and mental components not restricted to coping with diseases at the End of Life (EoL), but also in prevention and recovery. In these realms, spirituality/religion has been shown to be beneficial to health due to the promotion of healthy behaviours, positive psychological states, better coping with stressful events, and the strengthening of social networks and support (Oman and Thoresen 2005). In fact, disassembling spirituality into three components (i.e., transcendence, value-guidance and religious practices, Coyle 2002), it becomes positively connected with the adoption of healthy behaviours.

From shamans and traditional healers up to chaplains in contemporary hospitals, the connection between spirituality and religions with health and healing is ancient, quasi-universal and persistent. Powerful spells, mantras, or prayers, sets of repetitive actions or corporeal movements and performances, large ceremonies, and healing miracles, for millennia, have aimed to cure illnesses, ensure health to followers and make sense of death. This is true, all throughout the world, particularly in the past, when, in the Western world too, no official separation was hold between medicine, healthcare and clergy/spiritual leaders, who were often also physicians; and where, in Mediaeval times, for examples, the first hospitals to serve the general population were built by religious organisations (Koenig 2012). As known, in the West, differently from several other contexts in the world, (bio)medicine/allopathy and religion/spirituality have taken official markedly distinct directions. Additionally, starting from the French revolution along the processes of modernisation and industrialisation, it was argued that a progressive technologisation of healthcare has occurred in the Western context; this included self-care, and marked a switch from caring to a ‘cure-oriented’ model (Puchalski 2001). As also Bourdieu argued (Bourdieu 2014), scientific knowledge and experts around health have replaced in society religious symbols, figures, and practices, and have become the authority about ‘how to live via health, healing, and spiritual and bodily care’ (Larsen et al. 2020). Not only within non-Western spiritualities of the body, the realms of healing, care, and the divine have remained less demarcated, but also in the West, arguably, the historical separation has been reversing. The bond between religious institutions and medicine seems to have been strengthening, from the end of the last century, with a progressive inclusion of spiritual care into the medical and nursing practices (Cockell and Mcsherry 2012), and in research (Lalani 2020; Weaver et al. 2006). In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) was created in 1948, as the first integrated, state-funded hospital service in the country (Greengross et al. 1999). Spiritual and pastoral care departments have since been an integral part of hospitals, and chaplains are employed under the responsibility of the NHS to ensure that ‘all people, be they religious or not, have the opportunity to access pastoral, spiritual or religious support when they need it’ (Swift et al. 2015, p. 6).

While it is too hasty to talk of desecularisation (Bruce 2002), the growth in research and training around spirituality in healthcare is indicatitve of the broader shift towards a humanisation of care, which is holistic and person-centred (Cockell and Mcsherry 2012). Spiritual competence is also a key component of the growing model of culturally competent and compassionate care (Cochrane et al. 2019; Papadopoulos 1999, 2018). Spirituality and religion are crucial elements of an individual’s cultural values and beliefs, including health beliefs; and spiritual needs vary across cultural and ethnic groups (Busolo and Woodgate 2015). In this expanding paradigm of compassionate care. where cultural and spiritual competence is central, one feature seems crucial: that of a quality presence (also Hosseini et al. 2019) of the caregiver who can assist the patient in their suffering, when their psychological, physical, cognitive and spiritual resources cannot suffice without the presence of a human fellow. But how is this quality presence to be conceived?

Spiritual care as presence is a subjective and culture-based construct. However, there are also some transversal elements that we identified (Papadopoulos et al. 2021a). These are attention, active listening and support around patients’ existential and illness-related fears and meaning-making; their conceptions of an entity more powerful than the self and how this may link to the holy/divine and/or to their specific religious needs (for which a specialist should be involved); other dimensions, wishes and values, such as their search for inner peace, connecting with loved ones, listening to their favourite song/poem (Papadopoulos et al. 2020). As others have found (Ramezani et al. 2014), spiritual care involves compassionate and healing presence, a being there where a whole human-to-human contact is created (Papadopoulos et al. 2021a).

Spiritual care amidst the pandemic: study methods and results

Methods

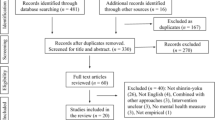

Both anecdotal accounts and evidence from available studies emphasised the lack of spiritual care during COVID-19 (Ferrell et al. 2020; Ribeiro et al. 2020; Roman et al. 2020), with the tragic result that many patients died alone. In light of this, the aim of our scoping study was to explore how spiritual care was covered by mass and social media, and by the websites of religious and non-religious organisations, as well as the websites of UK NHS Trusts during the first peak of COVID-19 in England (March–May 2020). The Internet-based scoping study of on-line evidence sources was guided by Levac and colleagues’ framework (Levac et al. 2010), and adapted to scope evidence different from academic and grey literature, i.e., websites, and social media postings. The source of information/stories could be about the patient, the nursing staff, the spiritual leaders, the families of patients, a journalist interviewing a patient, a friend of the patient or family. On-line sources selected included six online newspapers, 43 websites of NHS Trusts and organisations concerned with spirituality, and 62 sources from social media (Facebook and Twitter). Detailed methodology, tabular and descriptive presentation of results can be found elsewhere (Papadopoulos et al. 2020, 2021a).

Results

The results of this study are discussed below and are encapsulated into four fundamental themes in spiritual care delivery during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in England: (1) Absence/reduction of body contact and language during in-person spiritual care, including in the performance of rituals; (2) Non-digital, creative spiritual care to establish closeness-in-distance, via symbolic and creative actions, often performed in the domestic space; (3) Virtual, digital spiritual support, using digital technologies, both synchronically (e.g. live streamed masses and video calls) and asynchronically (e.g. recorded guided meditations and uploaded prayers); and (4) Voices from the COVID frontline: an ambivalent experience.

Absence/reduction of body contact and language

Where in-person spiritual support had not been discontinued, this had been severely reduced and modified, as often only emergency cases could be catered for. Spiritual care became a restricted, staggered, and on-demand service for emergency patients in those hospitals where chaplains could reach patients’ bedsides. In such cases where in-person support could be continued, the necessity of adhering to the stringent infection control measures affected the interpersonal interaction of spiritual care. The words of chaplains from our sources describe the experience of offering bed-side spiritual care to patients during the pandemic, and the ‘challenges of having to keep at distance when presence was most needed’ (Source #17).Footnote 1 Three interrelated aspects can be pulled out specifically: first, the infection control measures banning physical proximity; second, the compulsory use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) which heavily reduced body language and non-verbal communication—‘there are still the eyes… I hope you can still display a message of love with eyes’, a chaplain commented (Source #18); and third, the modification of some ritual acts. Another quoted example is that of anointment, the Christian sacrament that has the function of connecting the sick with God, giving them strength and preparing their body and soul for eternal life, ministered during the pandemic via a cotton bud and only on some parts of the sick person’s body:

we have to administer the oil using earbuds, which is a new measure, because we can no longer have skin-to-skin contact. We use the earbud to create distance, we wear gloves and then burn the earbud afterwards. (Source #17)

Another source (Source #4) refers to the spiritual communion as an ‘approved alternative in the absence of Holy Communion’ in times of plagues, such as the current pandemic (also Warren 2020). Even after death, physical contact changed, and loved ones must wait before being able to touch and experience that sense of connection with a now breathless body: ‘mementoes or keepsakes (for example, locks of hair, handprints, etc.) […] must be placed in a sealed bag and the relatives must not open these for at least 72 h’, a guidance document informs us (Source #19).

Non-digital, creative care to establish closeness-in-distance

A less reported change in spiritual care is a form of at-distance and self-spiritual care, conducted without the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT). This kind of support can be conceived as self-help and/or as an intentional and creative establishment of spiritual proximity with the loved ones, often performed in the domestic environment and in solitude. To establish an ‘invisible string’, as a source addressing young relatives suggested (Source #25), entails a powerful intention which can be made tangible thanks to some symbolic and creative actions, such as

listening to music; writing a message, hearts and bracelets - you could cut a heart shape from any material such as an old piece of clothing. The heart could then be attached to your loved one’s night clothes to be with them at all times); something to hold (with familiar scents) (Source #25)

lighting a candle or incense at home alone or with other members of your household, saying some prayers, reading from religious texts, meditating, playing some music, displaying a photo of your loved one, arranging some flowers or other meaningful objects or having some special food. Wearing particular clothes or going for a walk or drive to a special place might also be possible for you. […] Send a card or email to family or make a donation to charity in memory of someone (Source #24).

consider visiting a place with special memories, that helps you feel closer to your loved one. Write a goodbye letter – sometimes it’s easier to say exactly what you want by writing it down. Do something that mattered to you and your loved one. For example, listen to a favourite song, look through photographs or watch a favourite TV show (Source #26)

Other sources have reported the possibility of having masses by names, which is an example of dedicated intention within a religious rite, where the bodily presence of the participants is not there, and leaders and followers are asked to imagine that ‘no person is an island’ (Source #18).

Virtual, digital spiritual care

The most common alternative way of giving spiritual care has been the virtual provision, via different ICTs, such as smart telephones, tablets, smart apps like WhatsApp, FaceTime, and email. This means that spiritual care providers made themselves available virtually, primarily over the phone. Even the conduction of rituals has been made possible over the phone or virtually, as one source clarified in relation to the possibility of obtaining the Sacramental Absolution remotely (Source #4); or as another in relation to funerals, whereby a humanist organisation helps celebrants to conduct funerals digitally, ‘with many celebrants already reporting increased take-up of live-streaming’ (Source #29). These are examples of statements that we found in several English hospitals’ websites: ‘if necessary, much of the Chaplains’ work can be carried out effectively from home’ (Source #4), ‘we’ve [chaplains] introduced phone and FaceTime clinics for patients’ (Source #6), and ‘there is an offer of 1 to 1 telephone support for all and advice on spiritual care matters including religious practice’ (Source #7).

Two further uses of digital technologies in spiritual care have been identified. One consisted in the live virtualisation of collective religious rituals, which were live streamed at specific dates and times to followers. The second way is the asynchronous one, where neither spiritual care provider-receiver e-communication nor temporal simultaneity of the delivery/fruition of rites occur. Due to the government directives prohibiting gatherings and enforcing the closure of the places of worship, several hospitals, but mostly religious and inter-faith organisations, uploaded resources for spiritual care on their websites, such as prayers, recorded audios and videos of masses or talks from spiritual leaders, mindfulness exercises, guided meditations, and resources addressing EoL experience and bereavement.

Voices from the COVID frontline: an ambivalent experience

The last theme expresses the ambivalent experience of those at the frontline of spiritual care provision in relation to the changes presented in the three themes above. An EoL vignette of remote spiritual care narrated by a priest in England is illuminating (Source #18). On the one hand, we learn that an old ill lady ‘got a lot’ from chatting and praying together with the priest over the phone, and that, despite not having him ‘taking time to sit with’ her and giving her the ‘last rites’, it had made a great impact and difference. On the other hand, the priest confesses that he ‘was a bit taken aback thinking it was just a prayer over the phone’ (Source #18, emphasis added).

Other frontline providers echoed the perplexity of this priest, expressing a sense of a mutilated spiritual care. One chaplain more directly observed: ‘conversations through a digital device, however, still make a poor substitute for face-to-face interaction, especially when saying a final goodbye’ (Source #43). Another chaplain condensates the frustration of a largely silenced body: ‘I smiled at her to reassure her. Then I realised that she could not see my smile, because it was hidden behind my surgical mask’ (Source #41). Another one emphasises the importance of physical closeness between spiritual leaders and patients, because it offers relatives a way to ensure that their loved ones are cared for and supported in line with their faith practice: ‘there’s something about our proximity too, and people take comfort from the fact that we will go to be where their loved ones are’ (Source #6). Overall, there is widespread acknowledgement of the suffering of not being able to be physically close to someone, in addition of losing that loved person, as this source expresses: ‘this is particularly painful when someone important to us is so seriously ill that they might die, and we can’t be physically near them’ (Source #25).

Discussion

Blended being in spiritual care is an open issue

Technology, disembodiment, and solitude are three changes suggested by three of the themes resulting from our study and that affected spiritual experience, practices and care during the COVID-19 pandemic. These three elements are interrelated and revolve around the role of the body, the role of technology, and that of the other—intended as another human fellow. These phenomena are not new per se. But their fast combination and intensity in a moment of unprecedented health emergency and mass mortality invite us to reflect on the impact of the COVID-19 health disaster onto the spiritual care encounter, precisely in relation to the role of the body and the nature of being there for and with the other, in spirituality and caring.

As other studies have observed, the impossibility of being there sitting next to dying patients for many chaplains constituted an unprecedented limitation to their ‘moral agency’ and profession, only partially compensated by their hyper-presence on-line (Hart 2020; Theos 2021). All hospital staff have potentially been a source of spiritual care, from nurses (Taylor 2020) to cleaners (Source #38), testifying again in relation to the importance of physical presence as part of holistic, spiritual care (Drummond and Carey 2020). One of the few studies investigating the point of view of the sick people, or potentially sick, was conducted in a care home, and significantly found that ‘the reduction of physical contact with family leaves them craving contact, as a form of physical validation and therapeutic soothing’ (Drummond and Carey 2020). In general, both the experiences of chaplains/spiritual leaders, family members and sick ones appear to oscillate between a recognition that at-distance spiritual care, which entails a blended being, has some advantages—not least because technology is better than nothing—while also fundamentally lacking those ‘physical validation’, embodied silence, palliative touch and the ‘multisensorial being there’ (Byrne and Nuzum 2020; Murphy 2020).

E-presence, cyber-ritual, and digital spiritual care

Technology in spirituality and religion is an established field of knowledge, that of digital religion, which helps making sense of some of the recent changes of COVID-19 spiritual care (Campbell and Evolvi 2020). The relationship between ICT and religion/spirituality has been explored in the past three decades under different theoretical approaches. More encouraging views have been accompanied by less positive ones in the age to the Fourth Industrial Revolution and virtual communities (Rheingold 1995). Since the 1990’s, internet was seen as conducive to the development of new forms of rituals, and other innovations, including: the crafting of new identities, the emergence of fewer institutional religious leaders and less hierarchical communities; the perpetuation and innovation at the same time of rituals, pilgrimages and worship; and the presence of religious organisations, exponentially increasing proselytism and accessibility (Campbell 2007; Campbell and Vitullo 2016; O’Leary 1996).

The concept of ‘mediatisation’ theoretically informs some of this scholarly inquiry, and considers spiritual/religious practices as shaped by media (Hjarvard and Lovheim 2012). Another concept in digital religious study has been that of ‘third space’, which refers to that dimension in between on-line and off-line settings (Hoover and Echchaibi 2014). In this vein, some authors wondered how computer-mediated-communication in religious cyber-communities and ‘living-room rituals’ affected the participatory feeling inherent in rites (Kong 2001). Another line of inquiry focusses more on the agency of believers and communities in the use of technology, and it is referred to as ‘religious-social shaping of technology’ (Campbell 2007). An example is a study on how devotees overcome concerns about the purity of the virtual altar in a cyberpuja with medium-specific innovation, such as lighting incense in front of the screen, or clearing the browsing history (Karapanagiotis 2010).

More critical studies have developed reflections around the existential meaning and impact of religion and spirituality going massively digital. The marketisation of religions, rituals and leaders; the establishment of loose, flickering communities; a depleted sense of engagement and connection, both with others and with that universal breath that we discussed in the opening of this article; and the alienating consequences of disembodiment, hyper-privatisation and collage-identity of the neo-liberal subject: these elements have been pointed to as potential triggers of spiritual crises and leading ‘spiritual inner life […] to atrophy’ (Kinney 1995, p. 774). This argument in turn resonates with the social capital theory in health and illness, that we have introduced above and that points to the detrimental consequences of neo-liberalism in health (Turner 2003).

On the contrary, other scholars have explored how cyberspace is altering our sense of self and being human, and how it is opening up a new metaphysical dimension of spiritual quest as opposed to the physical materiality of the body (Wertheim 2000). In this perspective, the ephemeral essence of spirituality well matches the disembodied and often solitary spiritual experience in front of the screen connected to an invisible cyberspace (Brasher 2004). At the same time, new advanced technologies are challenging this fundamental bodily encounter in spiritual care. Within proliferating Anthropocenic, that is non-anthropocentric and non-humanistic scenarios, we do not know what holistic and ‘humanised’ care will look like, because the very nature of the human, the human body, and supposedly of our breath too, are situated and hybridised (Braidotti 2013; Haraway 2006). The relativising and de-centring of what being human entails is problematised even more in the arguments of multiple ontologies and pluriverses (Holbraad and Pedersen 2017; Kothari et al. 2019). The meaning and practices of being ‘Man’ are deconstructed as historical and political categories defining the norm and what is normal, that is man, white, European, heterosexual, and neurotypical. An excellent example to grasp a post-human approach to technology-mediated spiritual care and to think about human embodiment (Shildrick 2009) is the case of neurodivergent people. Many disabled people have been using digital technologies to communicate for many years and has long found this to have enriched their lives. The finding that PPE and lack of physical presence inhibit spiritual care may overlook the experiences of many autistic people, who may communicate without body language, and who may find physical proximity or touch uncomfortable or distressing—even in proximity of the abandonment of the body, that is death.

The body, the group, and the priest

All throughout history up to pre-COVID times, human groups have taken care of the dying and of their corpses after death, often within the context of congregational rites guided by a leader. Severe illnesses and dying are shocking events, for both the individual and the collectivity, around which arguably all cultures and religions have established very elaborate ritual practices. The ritual wrapping around death implies that both the dying and the dead ones are accompanied by members of society in their departure. It also often implies the presence of ministers, religious leaders, experts or intermediaries who assist the mourning community, including the dying individual, in their spiritual needs, guiding them through appropriate emotions, words, and actions in a moment of intense vulnerability. Death rituals are exceptionally good to grasp the importance of physical presence in spiritual care. In these collective rites, they take care of themselves and their suffering, to ensure the passage from the world of the living to that of the dead (van Gennep 2019). Death constitutes a threat to humankind itself and a disruption that challenges our existential meaning and values. Rites can be seen as structured communicative actions to render it intelligible (Tambiah 1981) and to give order/sense to this potentially chaotic social change. At the same time, they allow the equal sharing of the mourning experience by the ritual ‘communitas’ (Turner 1996). The special state of emotional sharing—the Durkheimian collective effervescence (Durkheim 2008)—is conducive to establishing solidarity and favouring catharsis. Being part of a shared experience simultaneously, made of physical movements and actions, verbal expressions and practical scheme, is integral to rituals (Bell 1990). In contrast, unless framed within specific spiritual, ascetic practices, or choices (Turner and Caswell 2020), dying alone is often constructed as a form of ‘bad death’ (Seale 1998). Solitary deaths are seen as undesirable, they lie out of current social norms and cultural scripts of dying well (Seale 1998). For this, they can contribute to disenfranchise grief, which cannot be acknowledge and processed—that is ritualised—by society.

During the pandemic, the simultaneous physical presence of three important actors of death rituals (the body, the group and the priest) had to cease. In live streamed rituals, synchronicity could be maintained, whereas in other cases spiritual practices became fully privatised behind the domestic walls. Generally, the one-to-one whole presence in EoL spiritual care was reduced, and when it could be offered, it was with a ‘COVID-limited’ body, avoiding proximity and skin-to-skin contact—using earbuds and smartphones, for example. Rituals had to change too, affecting both the interpersonal encounter and the collective participation. Even post-mortem treatment of COVID-19 corpses had to be altered worldwide, modifying the tangible-cum-symbolic processing of the bodies (Omonisi 2020). Similarly to rituals and death rituals, spiritual care is characterised by the central role of the body, as within the broader religion/spirituality field, spiritual care has also a prominent healing purpose. This particular caring goal of spirituality makes it more problematic to ‘go live’, as literature is suggesting, including this as well as another study we have conducted with health and social care professionals (Papadopoulos et al. 2021b, 2022). This is because, we maintain, healing and care sit within that ethical and existential dimension of not only being there, but of being-with the other (Heidegger 2019). Digital religion studies and concepts, such as mediatisation and third space, become therefore insufficient. If in Heidegger’s phenomenology, being-in-the world is fundamentally informed by the dimension of care, in Merleau-Monty’s philosophy, the world is one of intercorporeality, that is the interweaving of living bodies and embodied perceptions (Merleau-Ponty 2013). Such intertwinedness of being human, caring, corporeality is evident in spiritual care, as well as in death rituals, and it has been brutally shaken by the limitations posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Drawing from Durkheim’s functionalist approach to religion, in this article, we have addressed spirituality within the framework of spiritual care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The global infection disease has been an excellent laboratory to unveil the ongoing importance of religion/spirituality in our contemporary society, as well as the pivotal role of both physical presence and intercorporeality as well as of both digital and non-digital disembodied presence in spiritual care. Our study has explored changes and innovations in spiritual care during the outbreak and has corroborated existing literature conveying mixed views and experiences in relation to virtual and at-distance spiritual care. One view holds on to the inalienability of intercorporeality in that being there for the other, in moments of heightened vulnerability, when death is a possibility or imminent, and the meaning of human existence vacillates. Through the bodily flesh, the world and the others are perceived, understood (Merleau-Ponty 2013) and cared for—via healing touch or EoL holding hands. A nose-to-nose contact for the passing of immortality breath, or for turning society immortal, a Durkheimian reading would maintain, is necessary. The other view encapsulates experiences and ideas whereby at-distance spiritual care, which was very often supported by technology, proved not only useful, but also meaningful.

Literature in digital religion and existential media studies have posed existential questions around living in an increasingly digital world, particularly with the introduction of more sophisticated technology, such as artificial intelligence and augmented reality—but spiritual care is yet to be fully drawn into the discussion. In spiritual care, the debate stretches beyond an exploration of how digital spaces can impact ‘our understanding of life, death, and time to expanding our very notion of being in a digital-mediated world’ (Campbell and Evolvi 2020, p. 13; Lagerkvist 2017). Additionally, despite the fact that the idea of dying alone ignites a sense of abnormality, if spiritual care was relegated to an on-line service this must also reflect what society considered unimportant, beyond the matter of infection control measures (Yoeli and Edwards 2022). It also speaks to a call for an opening up to post-human theories able to factor in the element of care in new conceptualisations of being and being there with a ‘COVID-limited’ body. If the pandemic has altered religion and spirituality under several aspects, it must also be mutating our being as humans, and maybe it is showing us routes towards less confined or restricted selves—a blended being, able to care for others and connect with the mystery of life in new post-human, cyber-onto-cosmologies.

Notes

Sources’ references, with relevant details, including URLs, are provided in Table 1.

References

Bell, C. 1990. The Ritual Body and the Dynamics of Ritual Power. Journal of Ritual Studies 4 (2): 299–313.

Bono, J.J., T. Dean, and E.P. Ziarek. 2008. A Time for the Humanities: Futurity and the Limits of Autonomy. New York: Fordham University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt13x0cd3.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice (trans: Nice, R.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507

Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. 2014. Ce que parler veut dire: L’économie des échanges linguistiques. Fayard.

Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman (1st edition). Cambridge: Polity.

Braidotti, R. 2019. A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities. Theory, Culture & Society 36 (6): 31–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418771486.

Brasher, B.E. 2004. Give Me That Online Religion (None edition). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Bruce, S. 2002. God is Dead: Secularization in the West. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Busolo, D., and R. Woodgate. 2015. Palliative care experiences of adult cancer patients from ethnocultural groups: A qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 13 (1): 99–111. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1809.

Byrne, M.J., and D.R. Nuzum. 2020. Pastoral Closeness in Physical Distancing: The Use of Technology in Pastoral Ministry During COVID-19. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 8(2). https://journals.equinoxpub.com/HSCC/article/view/41625

Campbell, H. 2007. Who’s Got the Power? Religious Authority and the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12 (3): 1043–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00362.x.

Campbell, H., and G. Evolvi. 2020. Contextualizing Current Digital Religion Research on Emerging Technologies. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2 (1): 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.149.

Campbell, H., and A. Vitullo. 2016. Assessing Changes in the Study of Religious Communities in Digital Religion Studies. Church, Communication and Culture 1 (1): 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/23753234.2016.1181301.

Carel, H., M. Ratcliffe, and T. Froese. 2020. Reflecting on Experiences of Social Distancing. The Lancet 396 (10244): 87–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31485-9.

Carey, L. 2021. COVID-19, Spiritual Support and Reflective Practice. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 9(2). https://journals.equinoxpub.com/HSCC/article/view/42733.

Cochrane, B.S., D. Ritchie, D. Lockhard, G. Picciano, J.A. King, and B. Nelson. 2019. A Culture of Compassion: How Timeless Principles of Kindness and Empathy Become Powerful Tools for Confronting Today’s Most Pressing Healthcare Challenges. Healthcare Management Forum 32 (3): 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470419836240.

Cockell, N., and W. Mcsherry. 2012. Spiritual Care in Nursing: An Overview of Published International Research. Journal of Nursing Management 20 (8): 958–969. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01450.x.

Coyle, J. 2002. Spirituality and Health: Towards a Framework for Exploring the Relationship Between Spirituality and Health. Journal of Advanced Nursing 37 (6): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02133.x.

Csordas, T.J. 1993. Somatic Modes of Attention. Cultural Anthropology 8 (2): 135–156.

de Jager Meezenbroek, E., B. Garssen, M. van den Berg, D. van Dierendonck, A. Visser, and W.B. Schaufeli. 2012. Measuring Spirituality as a Universal Human Experience: A Review of Spirituality Questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health 51 (2): 336–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9376-1.

del Castillo, F.A. 2020. Health, spirituality and Covid-19: Themes and insights. Journal of Public Health (oxford, England). https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa185.

Drummond, D.A., and L. Carey. 2020. Chaplaincy and Spiritual Care Response to COVID-19: An Australian Case Study—The McKellar Centre. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy 8 (2): 165–179.

Durkheim, É. 2008. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (Ed. M.S. Cladis, trans: C. Cosman). Oxford: OUP.

Durkheim, É. 2013. The Division of Labor in Society (trans: G. Simpson,). New York, NY: Digireads.Com.

Ellison, C.G., and J.S. Levin. 1998. The Religion-Health Connection: Evidence, Theory, and Future Directions. Health Education & Behavior 25 (6): 700–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819802500603.

Ferrell, B.R., G. Handzo, T. Picchi, C. Puchalski, and W.E. Rosa. 2020. The Urgency of Spiritual Care: COVID-19 and the Critical Need for Whole-Person Palliation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 60 (3): e7–e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.034.

Foucault, M., L.H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and P.H. Hutton. 1988. Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Foucault, M., M. Senellart, Collège de France. 2010. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979. New York: Picador.

Greengross, P., K. Grant, and E. Collini. 1999. The history and development of the UK National Health Service 1948–1999 (Second). London: DFID Health Systems Resource Centre.

Haraway, D. 2006. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late 20th Century. In The International Handbook of Virtual Learning Environments, ed. J. Weiss, J. Nolan, J. Hunsinger, and P. Trifonas, 117–158. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-3803-7_4.

Haraway, D.J. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/C/bo3645022.html

Hart, C.W. 2020. Spiritual Lessons from the Coronavirus Pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01011-w.

Heidegger, M. 2019. Being and Time (trans: J. Macquarrie and E.S. Robinson). Martino Fine Books.

Hill, P.C., K. Pargament II., R.W. Hood, M.E. McCullough Jr., J.P. Swyers, D.B. Larson, and B.J. Zinnbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30 (1): 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00119.

Hjarvard, S., and M. Lovheim. 2012. Mediatization and Religion: Nordic Perspectives. Göteborg. Intl Clearinghouse on.

Holbraad, M., and M.A. Pedersen. 2017. The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hong, B.A., and P.J. Handal. 2020. Science, Religion, Government, and SARS-CoV-2: A Time for Synergy. Journal of Religion and Health 59 (5): 2263–2268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01047-y.

Hoover, S., and N. Echchaibi. 2014. Media Theory and the “Third Spaces of Digital Religion”. The Center for Media, Religion, and CultureUniversity of Colorado Boulder. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3315.4641.

Hosseini, F.A., M. Momennasab, S. Yektatalab, and A. Zareiyan. 2019. Presence: The Cornerstone of Spiritual Needs Among Hospitalised Patients. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 33 (1): 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12602.

Jupp, P.C. 2009. A Sociology of Spirituality. 1°. Farnham: Routledge.

Karapanagiotis, N. 2010. Vaishnava Cyber-Puja: Problems of Purity and Novel Ritual Solutions. Online - Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet: Vol. 04.1 Special Issue on Aesthetics and the Dimensions of the Senses. https://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/11304/.

Kinney, J. 1995. Net Worth?: Religion, Cyberspace and the Future. Futures 27 (7): 763–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-3287(95)80007-V.

Koenig, H.G. 2012. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730.

Kong, L. 2001. Religion and Technology: Refiguring Place, Space, Identity and Community. Area 33 (4): 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4762.00046.

Koss-Chioino, J., and P. Hefner. 2006. Spiritual Transformation and Healing Anthropological, Theological, Neuroscientific, and Clinical Perspectives. Lanham: Rowman Altamira.

Kothari, A., A. Salleh, A. Escobar, F. Demaria, and A. Acosta (eds.). 2019. Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary, 384. Tulika Books.

Lagerkvist, A. 2017. Existential Media: Toward a Theorization of Digital Thrownness. New Media & Society 19 (1): 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816649921.

Lalani, N. 2020. Meanings and Interpretations of Spirituality in Nursing and Health. Religions 11 (9): 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11090428.

Larsen, K., A.L. Hindhede, M.H. Larsen, M.H. Nicolaisen, and F.M. Henriksen. 2020. Bodies Need Yoga? No Plastic Surgery! Naturalistic Versus Instrumental Bodies Among Professions in the Danish Healthcare Field. Social Theory & Health. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-020-00151-z.

Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K.K. O’Brien. 2010. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implementation Science 5 (1): 69.

Martin, K., ed. 2010. The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Illustrated. Cologne: TASCHEN.

Mauss, M. 1973. Techniques of the Body. Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003.

Mellor, M.P.A., P.A.M.C. Shilling, and P.C. Shilling. 1997. Re-forming the Body: Religion, Community and Modernity. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Merleau-Ponty, M. 2013. Phenomenology of Perception, 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

Murphy, K. 2020. Death and Grieving in a Changing Landscape: Facing the Death of a Loved One and Experiencing Grief During COVID-19. Health and Social Care Chaplaincy. https://doi.org/10.1558/hscc.41578.

O’Leary, S.D. 1996. Cyberspace as Sacred Space: Communicating Religion on Computer Networks. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 64 (4): 781–808.

Oman, D., and C.E. Thoresen. 2005. Do Religion and Spirituality Influence Health? In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, ed. R.F. Paloutzian and C.L. Park, 435–459. Guilford Press.

Omonisi, A.E. 2020. How COVID-19 Pandemic is Changing the Africa’s Elaborate Burial Rites, Mourning and Grieving. The Pan African Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.23756.

Papadopoulos, I. 1999. Spirituality and Holistic Caring: An Exploration of the Literature. Implicit Religion 2 (2): 101–107.

Papadopoulos, I. 2018. Culturally Competent Compassion. Oxon: Routledge.

Papadopoulos, I., R. Lazzarino, S. Wright, P. Ellis Logan, and C. Koulouglioti. 2020. Spiritual Support for Hospitalised COVID-19 Patients During March to May 2020. Study report, Middlesex University London. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.10785.02409.

Papadopoulos, I., R. Lazzarino, S. Wright, P. Ellis Logan, and C. Koulouglioti. 2021a. Spiritual Support During COVID-19 in England: A Scoping Study of Online Sources. Journal of Religion and Health 60 (4): 2209–2230.

Papadopoulos, I., R. Lazzarino, C. Koulouglioti, S. Ali, and S. Wright. 2021b. Towards a National Strategy for the Provision of Spiritual Care and Support in Major Health Disasters. Study report, Middlesex University London. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.15753.57445.

Papadopoulos, I., R. Lazzarino, C. Koulouglioti, S. Ali, and S. Wright. (2022) Towards a National Strategy for the Provision of Spiritual Care During Major Health Disasters: A Qualitative Study. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 37: 1990–2006.

Pargament, K.I., and A. Mahoney. 2009. Spirituality: The Search for the Sacred. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0058

Pescosolido, B.A., and S. Georgianna. 1989. Durkheim, Suicide, and Religion: Toward a Network Theory of Suicide. American Sociological Review 54 (1): 33–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095660.

Puchalski, C.M. 2001. The Role of Spirituality in Health Care. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 14 (4): 352–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2001.11927788.

Ramezani, M., F. Ahmadi, E. Mohammadi, and A. Kazemnejad. 2014. Spiritual Care in Nursing: A Concept Analysis. International Nursing Review 61 (2): 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12099.

Rheingold, H. 1995. The Virtual Community: Finding Connection in a Computerised World. New. London: Minerva.

Ribeiro, M.R.C., R.F. Damiano, R. Marujo, F. Nasri, and G. Lucchetti. 2020. The Role of Spirituality in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Spiritual Hotline Project. Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa120.

Roman, N.V., T.G. Mthembu, and M. Hoosen. 2020. Spiritual Care—‘A Deeper Immunity’—A Response to Covid-19 Pandemic. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2456.

Schneider-Kamp, A. 2021. Health Capital: Toward a Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Construction of Individual Health. Social Theory & Health 19 (3): 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-020-00145-x.

Seale. 1998. Constructing Death: The Sociology of Dying and Bereavement. 1°. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shildrick, M. 2009. Corporealities. In Dangerous Discourses of Disability, Subjectivity and Sexuality, ed. M. Shildrick, 17–38. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230244641_2.

Swift, C., Chaplaincy Leaders Forum, & National Equality and Health Inequalities Team. 2015. NHS Chaplaincy Guidelines 2015 Promoting Excellence in Pastoral, Spiritual & Religious Care. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/nhs-chaplaincy-guidelines-2015.pdf

Tambiah, S.J. 1981. Performative Approach to Ritual. Oxford: British Academy.

Taylor, E.J. 2020. During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Should Nurses Offer to Pray with Patients? Nursing 50 (7): 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000668624.06487.72.

Theos. 2021. Care Under Covid-19: Providing Spiritual and Pastoral Support at a Distance. Theos Think Tank. London. https://www.theosthinktank.co.uk/events/2021/02/03/care-in-the-covid-crisis-what-does-spiritual-and-pastoral-support-look-like-at-a-distance

Tsing, A.L. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton Univ Pr.

Turner, B. 2003. Social Capital, Inequality and Health: The Durkheimian Revival. Social Theory & Health 1 (1): 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700001.

Turner, B. 2008. The Body and Society: Explorations in Social Theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Turner, B. 2014. Religion and Contemporary Sociological Theories. Current Sociology 62 (6): 771–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392114533214.

Turner, N., and G. Caswell. 2020. Moral Ambiguity in Media Reports of Dying Alone. Mortality 25 (3): 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2019.1657388.

Turner, V. 1996. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. 1°. New York: Routledge.

van Gennep, A. 2019. The Rites of Passage (Ed.: D.I. Kertzer, trans: M.B. Vizedom and G. L. Caffee), 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Warren P.J. 2020. Spiritual Communion During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anglican Compass. https://anglicancompass.com/spiritual-communion-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Weaver, A.J., K.I. Pargament, K.J. Flannelly, and J.E. Oppenheimer. 2006. Trends in the Scientific Study of Religion, Spirituality, and Health: 1965–2000. Journal of Religion and Health 45 (2): 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9011-3.

Wertheim, M. 2000. The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet: The Pearly Gates from Dante of Cyberspace to the Internet. Illustrated. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Wood, M. 2010. The Sociology of Spirituality: Reflections on a Problematic Endeavour. In The New Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Religion, ed. B.S. Turner, 267–285. Wiley-Blackwell.

Yoeli, H. 2021. The Psychosocial Implications of Social Distancing for People with COPD: Some Exploratory Issues Facing a Uniquely Marginalised Group During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Theory & Health 19 (3): 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-021-00166-0.

Yoeli, H., and D. Edwards. 2022. Contactless Time: No-Touch Rules Hit Vulnerable Children and Birth Families Where It Hurt. The Sociological Review Magazine. https://doi.org/10.51428/tsr.qcam9325.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lazzarino, R., Papadopoulos, I. Earbuds, smartphones, and music. Spiritual care and existential changes in COVID-19 times. Soc Theory Health 21, 247–266 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-022-00192-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-022-00192-6