Abstract

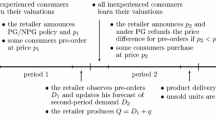

We consider a profit-maximizing seller who encounters consumers over two periods. The consumers face valuation uncertainty in the first period, which is resolved in the second period. We show that when the seller is capacity constrained, then there is a threshold capacity above which the seller prefers facing strategic, rather than myopic, consumers. Accounting for the seller’s stocking decisions, we find that the seller may stock higher levels of inventory when faced with strategic consumers than when faced with myopic consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson, C.K. and Wilson, J.G. (2003) Wait or buy? the strategic consumer: Pricing and profit implications. Journal of the Operational Research Society 54(3): 299–306.

Aviv, Y., Levin, Y. and Nediak, M. (2009) Counteracting strategic consumer behavior in dynamic pricing systems. In C.S. Tang and S. Netessine (eds.) Consumer-Driven Demand and Operations Management Models, vol. 131 of International Series in Operations Research & Management Science. New York: Springer, pp. 323–352..

Aviv, Y. and Pazgal, A. (2008) Optimal pricing of seasonal products in the presence of forward-looking consumers. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 10(3): 339–359.

Bansal, M. and Maglaras, C. (2009) Dynamic pricing when customers strategically time their purchase: Asymptotic optimality of a two-price policy. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management 8(1): 42–66. Copyright - ÂPalgrave Macmillan 2009; Last updated—2013-10-08.

Besanko, D. and Winston, W.L. (1990) Optimal price skimming by a monopolist facing rational consumers. Management Science 36(5): 555–567.

Besbes, O. and Saure, D. (2014) Dynamic pricing strategies in the presence of demand shifts. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 16(4): 513–528.

Cachon, G.P. and Swinney, R. (2009) Purchasing, pricing, and quick response in the presence of strategic consumers. Management Science 55(3): 497–511.

Chu, L.Y. and Zhang, H. (2011) Optimal preorder strategy with endogenous information control. Management Science 57(6): 1055–1077.

Coase, R.H. (1972) Durability and monopoly. Journal of Law and Economics 15(1): 143–149.

Dasu, S. and Tong, C. (2010). Dynamic pricing when consumers are strategic: Analysis of posted and contingent pricing schemes. European Journal of Operational Research 204(3): 662–671.

Du, J., Zhang, J., and Hua, G. (2015) Pricing and inventory management in the presence of strategic customers with risk preference and decreasing value. International Journal of Production Economics 164: 160–166.

Elmaghraby, W. and Keskinocak, P. (2003) Dynamic pricing in the presence of inventory considerations: Research overview, current practices, and future directions. Management Science 49(10): 1287–1309.

Espinosa, S. (2014) Clevelanders tell us how they feel about lebron james coming back. Retrieved July 11, 2014 from http://www.vice.com/read/clevelanders-tell-us-how-they-feel-about-lebron-james-coming-back.

Favale, D. (2014) NBA store sells out of lebron james cavaliers jerseys. Retrieved July 20, 2014 from http://bleacherreport.com/articles/2135699-nba-store-sells-out-of-lebron-james-cavaliers-jerseys.

Fay, S. and Xie, J. (2010) The economics of buyer uncertainty: Advance selling vs. probabilistic selling. Marketing Science 29(6): 1040–1057.

Fudenberg, D. and Tirole, J. (1991) Game Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Translated into Chinese by Renin University Press, Beijing: China.

Gul, F., Sonnenschein, H., and Wilson, R. (1986) Foundations of dynamic monopoly and the coase conjecture. Journal of Economic Theory 39(1): 155–190.

Hsiao, L. and Chen, Y.J. (2012) Returns Policy and Quality Risk in E-Business. Production and Operations Management, 21(3): 489–503.

Levin, Y. and McGill, J. (2009) Introduction to the special issue on revenue management and dynamic pricing. European Journal of Operational Research 197(3): 845–847.

Levin, Y., McGill, J., and Nediak, M. (2010) Optimal dynamic pricing of perishable items by a monopolist facing strategic consumers. Production and Operations Management 19(1): 40–60.

Li, C. and Zhang, F. (2013) Advance demand information, price discrimination, and preorder strategies. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 15(1): 57–71.

Li, J., Granados, N. and Netessine, S. (2014) Are consumers strategic? Structural estimation from the air-travel industry. Management Science. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2013.1860.

Liu, Q. and van Ryzin, G.J. (2008) Strategic capacity rationing to induce early purchases. Management Science 54(6): 1115–1131.

McIntyre, D.A. (2014) Lebron james would make cavaliers ticket price soar? Retrieved July 10, 2014 from http://247wallst.com/services/2014/07/10/lebron-james-would-make-cavaliers-ticket-price-soar/.

Melok, B. (2010) Fathead, company owned by dan gilbert, cuts lebron james pics to $17.41, benedict arnold’s birthyear. Retrieved July 9, 2014 from http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/basketball/fathead-company-owned-dan-gilbert-cuts-lebron-james-pics-17-41-benedict-arnold-birthyear-article-1.465840.

Mersereau, A.J. and Zhang, D. (2012) Markdown pricing with unknown fraction of strategic customers. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 14(3): 355–370.

Nasiry, J. and Popescu, I. (2012) Advance selling when consumers regret. Management Science 58(6): 1160–1177.

Nocke, V., Peitz, M., and Rosar, F. (2011) Advance-purchase discounts as a price discrimination device. Journal of Economic Theory 146(1):141–162.

Prasad, A., Stecke, K.E., and Zhao, X. (2011) Advance selling by a newsvendor retailer. Production and Operations Management 20(1): 129–142.

Shen, Z.-J.M. and Su, X. (2007) Customer behavior modeling in revenue management and auctions: A review and new research opportunities. Production and Operations Management 16(6): 713–728.

Stokey, N.L. (1981) Rational expectations and durable goods pricing. Bell Journal of Economics 12(1): 112–128.

Su, X. (2007) Intertemporal pricing with strategic customer behavior. Management Science 53(5): 726–741.

Su, X. (2009). A model of consumer inertia with applications to dynamic pricing. Production and Operations Management 18(4): 365–380.

Su, X. and Zhang, F. (2009) On the value of commitment and availability guarantees when selling to strategic consumers. Management Science 55(5): 713–726.

Swinney, R. (2011) Selling to strategic consumers when product value is uncertain: The value of matching supply and demand. Management Science 57(10): 1737–1751.

Tang, C.S. (2010) A review of marketing—operations interface models: From co-existence to coordination and collaboration. International Journal of Production Economics 125(1): 22–40.

Tuttle, B. (2012) Does anybody pay face value for sports tickets nowadays? Retrieved June 12, 2012 from http://www.business.time.com/2012/06/12/does-anybody-pay-face-value-for-sports-tickets-nowadays/.

Xie, J. and Shugan, S.M. (2001) Electronic tickets, smart cards, and online prepayments: When and how to advance sell. Marketing Science 20(3): 219–243.

Yin, R., Aviv, Y., Pazgal, A., and Tang, C.S. (2009) Optimal markdown pricing: Implications of inventory display formats in the presence of strategic customers. Management Science 55(8): 1391–1408.

Yuscavage, C. (2014). 23 cavaliers fans who don’t want to see lebron james back in cleveland. Retrieved July 23, 2014 from http://www.complexmag.ca/sports/2014/07/23-cavaliers-fans-dont-want-see-lebron-james-back-cleveland/.

Zhang, D. and Cooper, W.L. (2008) Managing clearance sales in the presence of strategic customers. Production and Operations Management 17(4): 416–431.

Zhao, L., Tian, P., and Li, X. (2012) Dynamic pricing in the presence of consumer inertia. Omega 40(2): 137–148.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix: Proofs

In this section, we provide proofs for the Lemma, Propositions, and Corollaries presented in the manuscript.

Proof of Lemma 1

We show that any feasible value of \(p_2\) is dominated either by \(p_2\in \{V_L,V_H\}\). Note that if \(p_{2}>V_{H}\), no consumers buy the product; therefore, \(p_{2}=V_{H}\) weakly dominates \(p_{2}>V_{H}\). If \(p_{2}\le V_{L}\), all consumers in the market in the second period attempt to buy a unit of product. However, setting \(p_{2}=V_{L}\) trivially generates more profit than setting \(p_{2}<V_{L}\). For the remaining interval of \(V_{L}<p_{2}<V_{H}\), notice that any price his range does not result in purchase of the product by low valuation consumers. Therefore, if the seller seeks to attract low valuation consumers, she must price the product at \(p_{2}=V_{L}\). If the seller is not interested in attracting low valuation consumers, she will simply set \(p_{2}=V_{H}\). Hence, \(p_2 \in {V_L,V_H}\). \(\square\)

The proofs of Propositions 1, 2, Corollary 1, and Proposition 3 are based on explicit and straightforward, albeit tedious, comparison of expected profits in the myopic and strategic cases, assuming we know the optimal pricing policy given a specific set of model parameters. Comparison of revenues is carried out using the two following tables (Tables 4, 5) which summarize all possible pricing decisions and resulting revenues.

Proof of Proposition 1:

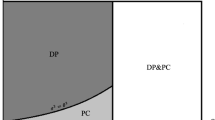

The proof is based on comparison of the expected profits in the myopic and strategic cases assuming we know the optimal pricing policy given a specific set of model parameters. As discussed, when the seller is faced with strategic consumers, then due to the nature of consumers’ valuations, there are eight possible pricing policies available to the retailer when facing strategic consumers. By Lemma 1, we have that \(p_2\in \{V_L, V_H\}\). The first period price, \(p_1\) is such that it induces exactly one of four possible consumer behaviors, provided in Table 3: (we use the notation presented in the paper and used for Figure 1) N, L, H, A. The expected revenues for each segmentation is given in Table 4.

When the seller faces myopic consumers, the seller has three pricing alternatives in the first period: set \(p_1=V_L\) to induce purchase by all consumers arriving in the first period purchase (behavior A), set \(p_1=V_H\) to induce purchase only from consumers with high valuations in the first period (behavior H), and set some arbitrary \(p_1>V_H\) which results with no purchase in the first period (behavior N). The expected revenues follow immediately. The expected revenues for the resulting segmentations are given in Table 5. Finally, we note that the seller can not induce a behavior L, where only low valuation consumers purchase in the advance selling period, without inducing purchase by high valuation consumers.

Taking the expected profits from Tables 4 and 5 in their limit as Q approaches infinity, for any set of model parameters, one can compare the revenues when facing strategic and myopic consumers and obtain the threshold in a straightforward manner (by making all possible comparisons), and thus Proposition 1 is achieved. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 2:

Follows in a similar manner to the proof of Proposition 1, removing the assumption that \(Q \rightarrow \infty\), while assuming a certain policy is optimal and comparing expected profits to ensure it is indeed optimal, allows us to achieve Proposition 2. \(\square\)

Proof of Corollary 1:

Stems from our knowledge regarding the optimal purchasing behavior and pricing policy, and is again a direct result of comparing the revenues between the strategic and myopic cases given a set of parameters. Note that when facing strategic consumers, the pricing policy inducing high valuation consumer purchases, \(p_1=\beta \cdot V_L+ (1-\beta )\cdot V_H\), is always dominated by the revenues generated when facing myopic consumers and selling at \(p_1=V_H\), giving us the desired result. \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 3:

The proof of this proposition is based on the following. Knowing the optimal pricing policy set by the seller when facing strategic consumers helps us (using the Tables 4 and 5) analyze the optimal pricing policy when facing strategic policy, and consequently conclude the relative magnitude of the stocking decision.

In case the optimal pricing policy, when facing myopic consumers is such that the purchasing behavior is H both periods (\(p_1=p_2=V_H\)), it is easy to verify (through straightforward comparison of profits) that the optimal policy, when facing strategic consumers is to sell to all consumers in the advance selling period, behavior A, and then set \(p_2=V_H\). By direct comparison of the estimated number of units sold (i.e., the demand part of the expected revenues) between the two cases, the desired results are achieved.

The argument in case the optimal advance selling period pricing decisions are, when facing myopic consumers, sell to all or to no consumers (i.e., \(p_1=V_L\) or \(p_1>V_H\), respectively), becomes trivial, as the optimal policy, when facing strategic consumers, must follow that of the policy facing myopic consumers, and hence there is no benefit from stocking a lower or higher inventory. In case the optimal pricing policy, when facing strategic consumers is such that the purchasing behavior is H in the advance selling period and then sell to all in the selling period (i.e., \(p_1=V_H, p_2=V_L\)), then it is easy to verify (through straightforward comparison of expected profits) that the optimal policy, when facing strategic consumers is to either sell to all consumers in the advance selling period, behvior A, and then set \(p_2=V_H\), or sell to all consumers in the advance selling period, behavior A, and then set \(p_2=V_L\). Indeed if the first case is optimal, in case consumers are strategic, and it is beneficial to hold higher inventory, that means that the seller facing myopic consumers can benefit from changing her optimal pricing policy to \(p_1=V_H, p_2=V_H\), but we know this is not the case. In the latter case, there is no added profit from deferring consumers to purchase in the second period, and since consumer are strategic, holding higher inventory will do just that. Hence, the results follow and we establish Proposition 3. \(\square\)

Notes

-

1.

We briefly discuss the case where the seller seeks optimal stocking and pricing decisions, i.e., Q is also a decision variable, towards the end of “Model analysis”. We numerically demonstrate our model’s ability to address this setting in “Numerical study”.

-

2.

Note that this is also a Bayesian Nash Equilibrium as the number of consumer types is finite.

-

3.

Note that inducing postponement of purchase behavior by all consumers can be easily done by setting \(p_{1}>V_{H}\). Similarly, inducing purchasing behavior such that all consumers buy in the first period, can be achieved by setting \(p_{1}<V_{L}\).

-

4.

Specifically, the seller can attempt to raise awareness to future valuation fluctuations, an issue we discuss further in “Conclusions”.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hermel, D., Mantin, B. Selling to strategic consumers: on the benefits of consumers’ valuation uncertainty and abundant inventory. J Revenue Pricing Manag 17, 146–165 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41272-017-0104-2

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41272-017-0104-2