Abstract

Digital technology (DT) plays an increasingly important role in the health sector. This study explores how national public health associations (PHAs) use DT to achieve their mandate. The World Federation of Public Health Associations canvassed and conducted a semi-structured interview with its national public health association members about their use of DT, the challenges they encounter in using it, and their experiences and thoughts as to how to assess its impact, both organizationally as well as on population health and health equity. The study found that digital technology plays an important role in some PHAs, principally those in higher income countries. PHAs want to broaden their use within PHAs and to assess how DT enables PHAs to achieve their organizational mandates and goals, including improved public health and health equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A national, nongovernmental public health association (PHA) serves to facilitate dialogue and critical thinking about and contribute to the development and implementation of solutions to complex social and ecosystem determinants of health.1,2 Dissemination of actionable information through communications networks is a key element that facilitates the capacity of PHAs to fulfill this role. PHAs use digital technologies (DT) in various forms: as ways and means to disseminate information, influence knowledge and actions, and connect people so they may share and promote best practices and policies for the public’s health. To date, no formal study assesses how PHAs use and evaluate the impact of these technologies.

In 2014, the World Federation of Public Health Associations (WFPHA) surveyed its national PHA members. DT ranked last as a priority issue (Figure 1). Of the 61 respondents, 8 PHAs indicated it to be very important, 26 ranked it as important, while the remainder ranked it as of no or little importance.3 In November 2014, the WFPHA Board of Directors approved a joint initiative with the Aetna Foundation to explore the use and impact of digital technologies for population health and health equity gains. This article reports on how PHAs use DT within their programmatic and advocacy activities and how they assess its impact.

Methodology

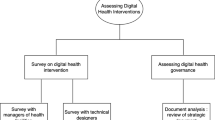

In June 2015, the WFPHA emailed its 85 PHA members, inviting them to voluntarily submit a synopsis describing their organization’s use of DT and how they assessed its impact on their programmatic and advocacy activities. The survey, in English, was pre-tested with two PHAs prior to distribution.

Responding PHAs were invited to take part in an in-depth structured interview focusing on three questions:

-

1.

How do DTs facilitate the capacity of a PHA to achieve its mandate?

-

2.

How do PHAs use DT as a core element in their programmatic and advocacy activities?

-

3.

Do and how do PHAs assess the impact of digital technologies on population health and health equity?

The interviews were conducted in October and November 2015. One author (YP) conducted the interview with one or two key officials representing the PHA. A translator or intermediary participated in two of the interviews.

All participating PHAs signed a consent form prior to the interview in which they agreed to be interviewed, agreed that the interview be recorded, and that the results be published. We do not attribute comments or observations to the people interviewed.

The low response rate (20%) to the initial call for information and the small number of PHAs subsequently interviewed may be a limitation to the current study. The issues raised, however, are consistent with previous WFPHA surveys of PHAs. The in-depth interviews present rich qualitative data about PHA experiences and opinions that had not been collected, analyzed or reported until now.

Results

Of the seventeen PHA respondents to the initial call (Australia, Brazil, Cameroun, Canada, China, Cuba, Vietnam, Ethiopia, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Norway, South Africa, South Korea, Uganda, UK, USA, and Vietnam), nine provided a synopsis about the DTs used. The Public Health Association of South Africa referred the invitation to its national health department, and the Faculty of Health Sciences/American University in Beirut submitted a synopsis of their work with refugee and displaced populations; both were subsequently invited to submit articles about their respective organization’s experiences with DT to be included in this special supplement. The Faculty of Public Health (UK) shared a member newsletter in which it discussed the use of DT for health.4 We conducted in-depth follow-up interviews with representatives of 10 PHAs (Australia, Cameroun, Canada, China, Nicaragua, South Korea, Uganda, UK, USA, and Vietnam).

How PHAs use DT

Figure 2 illustrates how these 10 PHAs reported the use of DT. The DT categories used are standardized terms and generally accepted categories. The three most frequent uses are websites, email blasts to members and social media, followed by e-newsletters and public service announcements. Crowdsourcing, gamification, and webinars were the least frequent uses of DT by PHAs.

The principal reasons for DT use by PHAs were as follows:

-

to communicate with their members;

-

to disseminate information about public health issues, best practices, and policies to their members, stakeholders, and the general public; and

-

to advocate, primarily to government representatives, for policies and programs that improve the functioning of their country’s health system and that have a positive impact on the public’s health.

DTs facilitated the establishment of communications within and supported the work of coalitions and alliances helping to leverage partner organizations’ networks through social media, reaching a wider audience while supporting more public health ambassadors for specific causes.

Websites

As of September 2015, 45 of the Federation’s 85 Full and Associate member PHAs manage an organizational website. One of the authors (JC) conducted an ad-hoc survey of these websites that same month. He found about 25% are active, up-to-date, and providing more than a single-dimension home page. Nine of the 10 PHAs interviewed for this article host websites.

Five of the interviewed PHAs indicated their websites were not as active as they would like, having low functionality and being inefficient in establishing user relationships. Only a few PHAs monitor their web traffic. Some PHAs offer secure web portals for members to access personal information and to renew memberships. Several PHA websites post information about their annual conferences and provide online abstract submission, conference registration, and registration fee payment functions.

Information technology and social media

Several PHAs report using DT to disseminate the latest developments and updates in public health research, in practice, and in policy advocacy. Email blasts and e-newsletters were the most frequently used.

The American Public Health Association (APHA—www.apha.org) sends out regular email blasts to 25,000 members several times each month. It publishes and distributes a monthly multi-page e-newsletter. APHA uses social media to alert the public and public health workforce when threats arise. During the Ebola outbreak in 2014, APHA used social media to disseminate timely information for public health workers, share facts about Ebola preparedness, put Ebola risks into perspective, and to share new research with national media outlets. The APHA reaches over 700,000 social media users on more than 20 social networks, including Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Social media platforms including Facebook are used to engage with communities and raise awareness about health challenges. In addition to its website (http://www.ansapnicaragua.org/), the Nicaraguan Public Health Association (ANSAP) manages a Facebook account (https://es-la.facebook.com/SaludPublicaNI) to announce seminars and workshops and post information about public health issues and research study findings. The ANSAP informs its members by email about webinars hosted by other organizations such as the Pan American Health Organization.

The Vietnam Public Health Association (VPHA—www.vpha.org) uses Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/vpha.org.vn/) to promote its activities, including tobacco control programs implemented in partnership with the World Lung Foundation. This allows it to connect to a wider audience and helped it and its partners brand themselves as credible public/consumer-oriented organizations. Its focus on Facebook as a communications medium was a specific element of the communications component of the VPHA’s 5-year strategic plan.

The APHA, the Canadian Public Health Association (CPHA—www.cpha.ca), and the Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA—www.phaa.net.au), use social media platforms to disseminate information, to engage with their members, and to promote their annual conferences. The UK Faculty of Public Health (FPH) uses DT to enhance its reach and impact through the frequent use of email blasts, informing members about upcoming courses and governance and programmatic issues. It uses social media and online surveys to gauge member opinions and views about its activities. The Chinese Preventive Medicine Association (CPMA—www.cpma.org.cn) began using social media through a Wechat (a China-based mobile text, video conferencing and voice messaging platform, accessible at https://web.wechat.com/) public account in January 2015. CPMA uses social media to promote physical activity, good nutrition, healthy eating, and chronic disease prevention among its members and the public.

PHAs also use YouTube to increase awareness of and disseminate information about public health issues. VPHA broadcasts videos from its provincial public health associations of experiences and success stories. In addition to the YouTube channel, the content is transcribed to a DVD and sent to provincial PHAs and other public health stakeholders. In this way, public health leaders at the provincial level are informed about developments in public health practices and achievements across the country. In 2013 the CPHA, in association with the Canadian Coalition for Public Health in the 21st Century (CCPH21) and the Canadian Network of Public Health Associations, released a bilingual video on YouTube highlighting the important social return on specific public health investments, including immunizations, child booster seats, drinking water fluoridation, and safer workplaces.5

Webinars and videoconferencing

Several PHAs use webinars and videoconferencing to facilitate communications within their governance bodies. They involve their members and other interested parties to discuss and find solutions for pressing public health issues. In 2015, the FPH launched an e-portfolio system to prepare for the Annual Review of Competence Progression and to provide access to new curriculum on public health competencies. In February 2016, the FPH hosted a webinar on the use of linked datasets as a tool for improved informatics and health services planning.6 The Brazil public health association (ABRASCO—www.abrasco.org.br) used webinars to prepare its second Master Plan for the Development of Information and Health Information Technology (PlaDITIS).7

The Korean Public Health Association (KPHA—www.kpha.or.kr) hosts virtual events wherein practitioners from remote areas can raise questions and share knowledge. KPHA reported these DT-based activities to be easier to implement and more cost effective compared to conventional modes of delivering professional development sessions. The KPHA also used video conferencing during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak (May–July 2015). Public health professionals from Saudi Arabia and Korea exchanged information on the MERS outbreak using advanced local networks including the Korea Research and Education Network (KoREN) and Cyberlab.

Mobile apps and SMS

CPMA developed a phone app to promote immunization by helping individuals locate nearby clinics, reserve appointments, and share their vaccination experiences. In March 2014, CPHA, Immunize Canada, and the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute released the ImmunizeCA vaccination mobile app8 onto three widely used platforms (iOS, Android, and Blackberry). A free bilingual mobile application, it provides users with a tool to manage their vaccinations. They have access to vaccination schedules across Canada plus evidence-based expert-reviewed information.

The Cameroun Public Health Association (ACASAP), with that country’s Ministry of Health, uses mobile phone technology and mobile phone apps like Whatsapp Messenger© (https://www.whatsapp.com) to communicate with rural community health workers. TB treatment adherence is monitored and information provided about treatment uptake. The application also facilitates reporting the use of insecticide-treated bednets. The Ethiopian Public Health Association (EPHA—www.etpha.org), in partnership with the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, began to use mobile phones to provide family planning information to front-line health workers.

The Uganda National Association of Community and Occupational Health (UNACOH—www.unacoh.org) used phone-based GPS technology to map tobacco accessibility (sales points) in selected areas near schools in Kampala.9 The same technology was used to map alcohol sales points in Kampala (visualized on Google maps). UNACOH also uses mobile phone SMS messages for health education and for reminding community members to tune into health-oriented radio programs.

Gamification and crowdsourcing

Some PHAs expressed interest in gamification (creating a game) as a means to promote their mission and the marketability of their products. Only one (APHA) has actually done so. Held in conjunction with the APHA’s 2015 annual conference, teams of technology builders teamed up with public health professionals at a Public Health Codeathon to create apps and programs to help people choose healthier food, manage their diabetes, and make other behavioral health decisions.10

Two PHAs (PHAA and CPHA) report membership special interest groups using crowdsourcing on a limited-scale to generate funds for topic-specific initiatives.

Challenges identified by PHAs in using DT

The PHAs have in common several constraints that limit their capacity to use DT as a means to improve their outreach and interaction with their members, the public, and the larger public health workforce. These include the following:

-

Lack of qualified people to design and manage a website and the lack of internal IT/DT competency within the PHA. Internal human resource IT capacity within the PHA is limited in many cases. Although some PHAs used volunteers to design and manage their websites, this often proved to be insufficient.

-

Lack of resources, including donor funding, to support core operational costs. While external funding might provide funds to mount an initiative-related webpage or some other DT, these do not cover operating costs of the PHA’s website or the use of the DT for other purposes. Some PHAs noted that DT-based interventions are usually project-specific, and operate only as long as funding is available. In some cases, several projects share a similar aim, for example to improve the delivery of primary health care services through community-based health personnel, but they use incompatible phone apps that can not be scaled-up into a national system.

-

Lack of an explicit communications strategy that includes DT within the association’s strategic plan. Linked to this is the need for leadership, both at the individual (CEO and staff) and collective (Board and membership) levels, that encourages and supports “change management” to overcome internal resistance, to experiment with new technologies, and to improve organizational effectiveness.

Although digital technologies may have an important role to play in improving population health and health equity, especially in Africa, Asia, and Latin America where recently the use of and access to inexpensive mobile phones has increased exponentially, PHAs in lower-income countries cited problems with local digital infrastructure. Problems with Internet connectivity and its associated costs, low bandwidth capacity, interruptions in electricity supply, the high costs of hardware, software maintenance, and the inadequate real-time videoconferencing capability (although Skype is available) limit their use of DTs. As reported at the 12th World Congress on Public Health, these factors were similar to those cited by PHA respondents to a WFPHA survey conducted in 2009 on the use of digital technologies—in other words, not much has changed over time.11

The PHAs also noted a challenge in moving beyond the use of DT for individual clinical and personal health (‘change your lifestyle/behaviour’) purposes. The task at hand is two-fold: first, how to use DTs to shift the discussion from an individual prescriptive level to one that explores the impact of determinants of health beyond the control of the individual; and second, how DT is used in and by other sectors and the impact this may have on population health and health equity.

Some PHAs have taken a lead in this regard. The CPHA developed an interactive platform (Frontline Health: Beyond Health Care) illustrating non-health sector initiatives that have had an impact on community health and health equity.12 The APHA posted on its website a comprehensive overview of health sector and non-health sector initiatives that have an impact on population health and health equity, including an innovative, interactive GIS-based (geographic information system) platform developed through the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, showing health equity patterns within US cities.13 , 14

Assessing the impact of digital technology on population health and health equity gains

Only a few of the PHAs reported conducting evaluations of the effectiveness and impact of DTs. The tendency is to measure process and output–the number and geographic location of people accessing a website, a web page, or uploading an app, and the frequency of such ‘hits’–rather than outcomes. None of the PHAs assessed the impact of DT on population health and health equity gains.

The VPHA, for example, monitors the number of visits to its online articles, newsletters, and the Vietnam Journal of Public Health. To date, it has logged over 7.4 million visits to its website since its launch in 2006. UNACOH attempts to determine its reach and the impact of its health-related SMS through audience feedback via telephone and texts received during the radio-based health programs it sponsors. The CPHA uses Google Analytics to ascertain the number of hits and re-tweets, duration spent on specific webpages, and the geographic location of hits. It also analyzes comments received. The APHA uses similar metrics.

The ImmunizeCA mobile app research team assessed the effectiveness of promotional strategies in driving uptake and use of the app, but has not as yet carried out an evaluation as to the app’s influence on immunization rates. The research team found that while app use analytics are a valuable tool, understanding how to interpret the analytics data requires a certain degree of sophistication, including a good understanding of analytic tag structure.15 They recommend working closely with the software development team when implementing in-app analytics for health applications.16

The Canadian, USA, Australian, and Vietnam PHAs noted that DT can strengthen partnerships and facilitate the work of coalitions for advocacy, health awareness, and education purposes. The PHA of Australia formed a virtual alliance with the National Alliance for Action on Alcohol; the APHA a coalition with the CDC and Friends of the Health Resources and Services Administration on key public health issues; the CPHA hosts the Canadian Coalition for Public Health in the 21st Century (CCPH21) website, an alliance of almost 30 national NGOs and professional associations. The VPHA found that allowing participants to use the ‘Like, Share, and Invite’ functions of its health promotion and knowledge mobilization events posted on the web helped strengthen links with partner organizations and raised public awareness on health issues. As cited by both the PHAA and the VPHA, DT has proven to be a means to reach out to audiences that would generally not be accessible to the PHA.

While PHA respondents were unanimous in citing the need to enhance the capacity of PHAs to evaluate their use of DTs—not only how they affect the programmatic, governance, operations, and advocacy activities, but whether and how they have an impact on population health and health equity. As one PHA executive director remarked, it is difficult (though not impossible) to show ‘cause and effect’ of DT on health outcomes, particularly with respect to the social determinants of health, when the methodologies to do so are not well developed and funding to support such assessments not readily available.

Notwithstanding these challenges, there was consensus that PHAs should include the evaluation of DT impact on population health and health equity gains within the communications component of their organizational strategic plans. One PHA representative commented: “It’s not just about the number of people who are vaccinated or who did not contract a disease; it’s also about how their education, their job security, the transportation systems to which they have access and can use, the quality of housing, etc. has had an impact on their health. It’s looking at all the determinants that affect health. DT can help us do that, and we should explore how to make it work for us.”

Discussion

Public health associations are using digital technologies in many ways: in their governance, policy and advocacy, for mobilizing partnerships and taking action to identify and solve health problems, for informing, educating, and empowering people about health issues, for analyzing and investigating health problems and hazards, for contributing to create and maintain a competent public health workforce, and as a means to improve the effectiveness/accessibility and quality of public health services. That being said, the breadth and scale of use of DT by PHAs depends on the number of PHAs that use them and the ways in which they are adopted and used.

The fact that PHAs in higher income countries tend to have websites that are maintained, kept current, and use more advanced and sophisticated digital tools than their counterparts in lower-income countries is an equity issue. The global IT network infrastructure is growing rapidly, including both undersea and overland cables and wireless. Due to the increasing access to robust connectivity, the growing cadre of people with training and experience in the design and use of DTs, the demand by PHA members and the public health workforce for DT, there is increasing pressure on all PHAs to adopt DT in their operations. Boards and PHA staff want to include DTs as a component of a PHA’s strategic plan with associated allocated resources. How can PHAs address IT equity issues within the community of global public health associations and communities? Planning for robust, broadband connectivity in the near future will be important for PHAs.

Our PHA respondents acknowledged the importance of carrying out a robust and independent assessment of the effectiveness and utility of DT, not only on the association’s programmatic, advocacy, and operational capacity, but also to learn how the use of DT impacts population health and addresses health equity issues. While process and output metrics provide useful information to the PHA in terms of the volume and frequency of ‘hits’ on a website, they provide little information about the ‘value-added’ of DT on the ‘demand side’ of the coin, to improve population health and contribute to better health equity.

Elsewhere, DTs have been defined as “Disruptive Technologies”.17 PHAs are encouraged to explore fully the transformative potential (positive as well as negative) of integrating digital technologies into their operational and strategic plans to support and enable their long-term goals of improving public health.

If PHAs are advocates for improved health and health equity, then assessing how their actions promote citizen engagement and activism and the success of their advocacy strategies in changing the way things are done would be appropriate metrics. The methods and metrics exist, one example being Change.org, an online platform that connects people around the world and across cultures to speak out and take action on issues of concern to them (https://www.change.org). It is a matter of investigating how PHAs can adapt these resources to their needs.

As DT continues to evolve, are PHAs to facilitate the introduction of DT into PH activities? As one PHA representative reminded us, DT can be a double-edged sword. It can help make PHAs more effective and efficient as organizations; it can broaden the reach of PHAs and help ensure that the products and services they offer are relevant and useful; and they can contribute to improving population health and health equity. But at the same time, DT brings high expectations: the public and decision-makers will expect the streaming of reliable, informative, up-to-date, and pertinent information on a continuous basis in a form that is ‘consumable.’ This requires a certain set of sophisticated skills, sustained organizational capacity, and investment to assure this will happen. It also requires PHAs be able to use multiple DTs and to have a full understanding of which tools to use for what purpose.

So where do PHAs go from here? Based on our analysis, we suggest the following ideas to advance the use of DTs by PHAs:

-

PHAs already using DTs should examine their impact (are they effective tools for the purpose they are designed to serve? Do they have an impact on population health and health equity?) and how DTs could be used better to serve the PHA’s organizational needs and the needs of its members, the public health workforce, and the public;

-

PHAs should incorporate DTs and allocate/reallocate resources for their adoption and management into strategic and business plans, along with plans to assess the impact of DTs on the PHA’s mandate and on health and health equity;

-

WFPHA should put into place a program to assist PHAs, especially those in middle- and lower-income countries, develop their organizational capacity to use and assess DTs. PHAs with experience in using and assessing DTs could mentor other PHAs and provide financial and technical assistance to help build DT capacity;

-

WFPHA should work with PHA members to develop a DT evaluation framework. How do other organizations and the private sector assess the impact of DTs? Can WFPHA customize and adapt methodologies and metrics to the needs of PHAs, including how to assess the inter-sectoral impact of DT on health and on building relationships with software developers; and

-

WFPHA host a session during the 15th World Congress on Public Health, bringing together PHAs, multilateral organizations such as the WHO, Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC), and organizations outside of the health sector with experience in using and assessing the impact of DTs. This could lay the groundwork for a global action plan on the use and assessment of DTs on population health and health equity gains.

Conclusion

Digital technology plays an increasingly important role in the health sector. PHAs are just beginning to ‘scratch the surface’ where it comes to using DT to achieve their organizational mandate and goals. There is room for improvement, not only its use among PHAs, but also broadening and enhancing how it is used. PHAs also should develop the capacity to assess the impacts of DT, both in terms of PHA organizational and programmatic capacity, but also how DT contributes to improving the public’s health and to addressing health equity issues.

As DTs continue to evolve in terms of their technological sophistication and the way they are used by individuals and communities around the world–including professional communities–the last thing PHAs want to do is ‘miss the boat.’ These associations’ relevance could diminish and their organizational sustainability be at risk. Now is the time for PHAs and the WFPHA to become actively engaged within this worldwide movement.

Editors’ Note

This article is one of six commissioned articles in a Special Sponsored Issue of the Journal of Public Health Policy in 2016, The Use and Impact of Digital Technologies on Population Health and Health Equity Gains .

References

Chauvin, J. (2013) Millennium development goals: Progress, lessons learned and the post-2015 path for sustainable human development from a public health perspective. A presentation made at the 20th Canadian Conference on Global Health, Ottawa (ON), 27 October 2013. http://www.ccgh-csih.ca/assets/CanadianConferenceonGlobalHealthJC.pdf. Accessed 2 December 2015.

Canadian Public Health Association (2011) The Public Health Association Movement: 25 years of building a civil society voice for public health. Ottawa: CPHA. http://www.cpha.ca/uploads/progs/_/sopha/sopha_publication_s.pdf. Accessed 2 December 2015.

Shukla, M., and Chauvin, J. (2014) Gauging the organizational health of national public health associations: a determinant of their capacity to have an impact on human health. Presentation made at the American Public Health Association’s 142nd annual meeting, New Orleans. 20 November 2014.

Faculty of Public Health. (2014) Oh, brave new world: how technology can make us better. Public Health Today. London (UK): UK Faculty of Public Health: December 2014. http://www.fph.org.uk/uploads/PHT%20Dec%202014.pdf. Accessed 2 December 2015.

Canadian Public Health Association. (2013) Public Health is ROI. Ottawa: CPHA. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVZxtuZhN_M&feature=youtu.be.

Faculty of Public Health. (2016) Commissioning workshop: Informatics in health and care service planning. http://www.fph.org.uk/events/commissioning_workshop:_informatics_in_health_and_care_service_planning. Accessed 28 January 2016.

ABRASCO. (2013) 20 Plano Director para o Desenvolvimento da Informação e Tecnologia de Informação em Saúde. 20PlaDITIS 2013–2017. Available at: http://www.abrasco.org.br/site/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/GT_informacao_plano-diretor.pdf.

Immunize Canada. (2015) ImmunizeCA App. Ottawa: Immunize Canada. http://www.immunize.ca/en/app.aspx. Accessed 2 December 2015.

Sekimpi, D. et al. (2013) Restructuring tobacco retail environments in Low and Middle-Income Countries. Poster presentation at National Conference on Tobacco or Health (Ottawa, Canada: November 2013). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278244002_Restructuring_tobacco_retail_environments_in_Low_and_Middle-Income_Countries.

American Public Health Association. (2016) APHA brings technology, health together. Codeathon teams address life expectancy at their third annual event. The Nation’s Health. Washington (DC): APHA. Vol 45(10) http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/45/10/4.1.full. Accessed 2 February 2016.

Alles, M. (2009) Experiences and challenges of IT-based collaboration with public health associations. A presentation delivered at the session on using ICT to enhance public health capacity during the 12th World Congress on Public Health (Istanbul, Turkey: 1 May 2009). https://wfpha.confex.com/wfpha/2009/webprogram/Paper7430.html. Accessed 2 December 2015.

Canadian Public Health Association. (2013) Frontline Health: Beyond Health Care. Available at http://cpha.ca/en/programs/social-determinants/frontlinehealth.aspx. Accessed 2 December 2015.

American Public Health Association. (2015) Topics & issues: health equity. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity. Accessed 15 December 2015.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2015) Maps to #CloseHealthGaps. http://www.rwjf.org/en/our-topics/topics/health-disparities.html. Accessed 15 December 2015.

Atkinson, K. M., Westeinde, J., Hawken, S., Ducharme, R., Barnhardt, K., & Wilson, K. (2015). Using mobile technologies for immunization: predictors of uptake of a pan-Canadian immunization app (ImmunizeCA). Paediatric Child Health, 20(7), 351–352.

Atkinson, K. M., Ducharme, R., Westeinde, J., Wilson, S. E., Deeks, S. L., Pascali, L., & Wilson, K. (2015). Vaccination attitudes and mobile readiness: a survey of expectant and new mothers. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 11(4), 1039–1045.

Zimlichman, E., & Levin-Scherz, J. (2013). The coming golden age of disruptive innovation in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(7), 865–867. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2335-2.

Acknowledgements

The World Federation of Public Health Associations thanks the Aetna Foundation for assistance funding this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

The online version of this article is available Open Access

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chauvin, J., Perera, Y. & Clarke, M. Digital technologies for population health and health equity gains: the perspective of public health associations. J Public Health Pol 37 (Suppl 2), 232–248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-016-0013-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-016-0013-4