Abstract

This article addresses a curiously neglected question, namely why do the vast majority of Finnish MPs—one of the highest levels in the world—hold a seat on the municipal council? The basic presumption is that Finnish parliamentarians are not first and foremost ‘office-seekers’; they do not seek municipal council office as a primary goal. Rather, they view municipal elections as a means of attaining localness, either as a personal vote-earning attribute (PVEA) or then as a representational attribute, bolstering their credentials as ‘local MP’ for the municipality. To test this reasoning, the analysis focuses on MPs’ decisions on whether to contest the four municipal elections between 2008 and 2021 (n = 796). The results show that the incentive to ‘cumulate’ is greatest for first-term legislators and those occupying marginal list positions at the previous general election, but that the incidence of dual mandate-holding does not rise systematically with the size of the municipality whilst national celebrity trumps localness as the primary vote-earning attribute. The evidence is also consonant with the view that dual mandate-holding is as much a representational merit as an electoral imperative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At the June 2021 Finnish local government elections (kunnallisvaalit), delayed for 2 months by the COVID pandemic, the serving prime minister, three former prime ministers,Footnote 1 over four-fifths of incumbent parliamentarians,Footnote 2 more than nine-tenths of the cabinetFootnote 3 and several members of the European Parliament gained a seat on a municipal council, making Finland a significant, albeit in the comparative literature neglected, case of dual mandate-holding. The practice of holding two or more elected offices simultaneously—the cumul des mandats (France), ‘double jobbing’ (UK), a dual mandate (Ireland)—or what is referred to here as the Finnish-style cumul—is an entrenched feature of legislative and electoral politics in the country. The proportion of first-term Finnish parliamentarians who became dual mandate-holders reached almost 90% in 2019 and averaged more than 80% over the four general elections between 2007 and 2019. It is not only first-term MPs that ‘cumulate’. Over the eight municipal elections between 1992 and 2021 an average of 72.1% of all MPs held a dual mandate and, as Table 1 reveals, there has been an upward trend since the turn of the new millennium (Borg and Pikkala 2017). In short, the pathway to parliament has been via the municipal council and the road to remaining in parliament has run via the municipal council. Very few Finnish MPs will not have held a dual mandate at some point in their political career.

The incidence of the Finnish cumul has run at a level broadly comparable to Belgium, where between 1995 and 2014 the cumul averaged 70.5% (Van der Voorde 2019, 2020), and it has been substantially higher than in other countries covered in the literature on dual mandate-holding. For example in Sweden in the late 1980s, a relatively modest 43% of MPs were multiple office-holders (Esaiasson and Holmberg 1996, p. 288) and this figure had dropped by the 2014–2018 Riksdag to 35.8% of parliamentarians who held a municipal council seat and 4.9% that held mandates at municipal, county and national levels (Karlsson 2018a). In Ireland in 2001, just prior to the abolition of the dual mandate in 2003, 68.1% of Dáil TDs were serving county councillors. True, Finland may not be a limiting case of the cumul des mandats. According to the 2012 Jospin commission, 82% of French National Assembly deputés and 77% of senators held a dual mandate whilst in Estonia in 2021 an estimated 85% of Riigikogu MPs held a dual mandate.Footnote 4 But the extent of the Finnish practice has none the less been notably high in comparative perspective.

In recent work in the Belgian context, Van der Voorde (2019, p. 149) has challenged the conventional wisdom on the dual mandate by demonstrating that there is no electoral increment accruing from cumul-holding when compared with single office-holders. This begs the central ‘why question’ posed in this article: Why do the vast majority of Finnish MPs hold a seat on the municipal council? What do they hope to gain—or not to lose—by doing so?

In seeking to answer these questions, this study constitutes the first in any language to address the whys and wherefores of the Finnish cumul. Theoretically, its originality lies in the way it seeks to tie the incentive to ‘cumulate’—that is, the institution of the cumul—to (i) the relative value of ‘localness’ as a personal vote-earning attribute (PVEA) and (ii) the value of localness as a representational attribute, underpinning and legitimising the parliamentarian’s credentials as ‘local MP’ for the municipality. Localness, operationalised as membership of the municipal council, is viewed multi-dimensionally as an MP resource, a strategic party resource as well as a resource for citizens in making their voting decision. Empirically, the study draws on the decisions of parliamentarians whether to contest the four municipal elections between 2008 and 2021 (n = 796) and it presents four hypotheses relating the relative utility of localness—and by extension the incentive to ‘cumulate’—to (i) the length of an MP’s parliamentary incumbency; (ii) his/her electoral marginality; (iii) variability in municipal magnitude; and (iv) the (possible) existence of countervailing PVEAs. The results show that the incentive to cumulate is greatest for first-term legislators and those occupying marginal list positions at the previous general election, but that the incidence of dual mandate-holding does not rise systematically with the size of the municipality whilst national celebrity trumps localness as a vote-earning attribute.

Incidentally, with barely a handful of exceptions, all the 796 MPs analysed in this article who sought a municipal mandate, gained one. For example, the first-term MP, Mikko Kinnunen, representing the Centre Party in the Oulu constituency, was elected to the Reisjärvi Municipal Council with a modest 71 preference votes, whilst the veteran Left Alliance legislator Markus Mustajärvi gained election with a mere 37 votes in Savukoski in the Lapland constituency. In other words, those MPs who have sought a dual mandate between 2008 and 2021 have in practice always acquired one. It is the question of why dual mandate-holding has been so prevalent that is our main concern.

The structure of the article is as follows. The first section reflects on the longevity and institutional embeddedness of the dual mandate in Finland. The cumul is then set in an electoral system context, bringing out the incentive to cultivate a personal vote, the high incidence of intraparty incumbency defeats and the potential costs of seeking to combine a national and local mandate. The third and fourth sections focus on the central concept of localness, which then informs and structures the hypotheses—three concerning the whys and a fourth the ‘why nots’ of the cumul. Following a presentation of methods and results the concluding remarks pull the threads whilst also pointing to the limits of an ‘electoral resource’ explanation for the Finnish cumul.

The institutional embeddedness of the Finnish cumul

The institution of the cumul is deeply embedded in the Finnish political culture. It dates back to the earliest years of Finnish independence when municipal parties, in pushing a local councillor (Mylly, 1989), sought area representation in parliament.Footnote 5 The practice of dual mandate-holding has been fostered by the open and inclusive rules on candidate eligibility in municipal elections, whilst today parliamentarians readily justify and by extension, legitimise the cumul as an integral part of their representative task. These points warrant brief elaboration.

The cumul has spanned the entirety of the independent Finnish republic, contributing to re-integrating Red politicians after the 1918 civil war (Soikkanen, 1970; Iivari, 2007)Footnote 6 and subsequently becoming rooted in the country’s political culture. The origins of the cumul can be traced to the report of the Municipal Committee (kunnallislakivaliokunta: mietintö 5/1917) which prepared the ground for the first modern Local Government Act in 1917 (the year of Finnish independence). The Act defined candidate eligibility very broadly. “Candidates for local government office should be open to all persons in a municipality with voting rights, who live in the municipality, manage their own affairs and finances and have full citizenship rights (kansanluottamus nauttiva)”. In this way, the Act brought the franchise for electing municipal councils and the rules on candidacy into line with those for general elections and abolished the practice of only landowners having voting rights—the number of votes corresponding to the area of land owned (manttaalimäärä). It also permitted all 24-year-old men and women to vote and run as candidates in municipal elections (Lindman 1968, pp. 97–104, 323) which were held on an annual basis until 1925 with one-third of the council retiring every year.

It is a measure of the institutional embeddedness of the cumul that the ‘Democracy 2007 Committee’, set up to assess the functioning of representative democracy in Finland—and to make recommendations for strengthening it—did not consider the impact of the dual mandate. This was despite the fact its remit was to “evaluate the role of the parties, electoral system and local government from the standpoint of [enhancing] the opportunities for civic participation and influence” (komiteamietintö 2005:1). Clearly, the legitimacy of the cumul was taken as read.

Whilst the rules on municipal council candidacy have facilitated the cumul, they do not account for the scale of the practice and they do not, of course, require MPs to run for local office. That they routinely do so, and why they say they do, can be gleaned from a sample of the ‘on the record’ responses of incumbent parliamentarians. Typically, “I am Sastamala municipality’s only MP and consequently I keep the local council abreast of what’s going on in parliament”(Arto Satonen—National Coalition Party). “It’s a good thing that first an MP participates in the law-making process in the Eduskunta and can then observe how laws function on the ground in the municipalities” (Arto Pirttilahti—Centre Party). “For an MEP a municipal council seat keeps your feet on the ground and your roots in home soil” (Merja Kyllönen—Left Alliance Party). “An MP’s work in parliament and on the town council is complementary and reinforcing” (Jouni Ovaska—Centre Party). “A municipal council seat allows MPs to inform and be informed – to inform the council of relevant parliamentary developments and be informed about [properly conversant with] local matters” (Timo Korhonen—Centre Party).Footnote 7

Clearly, however, the purported role of intermediary between the national state and local state does not of necessity require membership of the municipal council, raising doubts about whether this ‘channel of communication’ rationale really explains the prevalence of dual mandate-holding in Finland. An alternative would be to look to electoral incentives.

The electoral system context

Preferential voting systems incentivize personal vote-seeking in varying degree (Carey and Shugart 1995; Crisp et al. 2007; Cheibub and Sin 2020; Crisp et al. 2021). This is particularly so in Finland where in both general and municipal elections citizens are obliged to opt for a single candidate on one of the party lists; the candidate nomination process is inclusive and decentralised (Arter 2021a); in all but the Social Democrats candidates appear on the lists in alphabetical order; and, unlike closed list PR, there is no pre-rank ordering of candidates. Whilst the aggregate list vote determines the allocation of seats to the list, they are apportioned on the basis of individual candidate totals. Personal votes count and this creates the logic of personal vote-seeking and competition between candidates of the same party (co-partisans) as well as rival parties (Shugart 2008).

Indeed, intraparty incumbency defeats, although not unique to Finland (Katz 1985; Katz and Bardi 1980; Villodres 2003; Gallagher 2008; Dodeigne and Pilet 2019; Passarelli 2020), have been commonplace. When viewed over the 15 general elections between 1966 and 2019, there has been a greater chance of a Finnish MP succumbing to defeat at the hands of a co-partisan than to a candidate of a rival party. This can be seen from Table 2 which, drawing on the official statistics (tilastokeskus—https://www.stat.fi), shows that of those incumbents going down to inter-party and intraparty defeats over the period 1966–2019 (n = 763) an average of 53.7% (n = 410) have lost out to a candidate from the same party rather than a rival party. Inter-party defeats accounted for 46.3% (n = 353) of all losses.

Intraparty defeats rankle and displaced incumbents may well chart a road back to parliament by engaging actively in the work of the municipal council. In so doing they could pose a not insignificant threat to those MPs they lost out to at the earlier general election. Over the 15 general elections between 1966 and 2019 approaching one-third (30.6%) of parliamentarians going down to an intraparty defeat subsequently returned to the Eduskunta either as a re-elected MP or deputising for a member who has died, retired through illness, been elected to the European Parliament or moved to a role outside politics.

The municipality is the basic administrative unit for general (Eduskunta) and local government elections in Finland. Municipal elections are held every 4 years at the mid-point of the parliamentary term (Borg 2018a). The June 2021 local government elections were contested in 293 municipalities across the 12 mainland Finnish constituencies, the number of elected councillors ranging from a minimum of 13 in municipalities with at most 5000 inhabitants to at least 79 where the population exceeds half a million (Table 3). The largest, the Helsinki City Council, presently comprises 85 members. Candidates must live in the municipality and not be employed in leading administrative positions in the municipality. Every party or (multiparty) electoral alliance (vaaliliitto) is entitled to run at most one and half times the number of council seats to be filled. Importantly, unlike Sweden (Karlsson 2018b), general elections and municipal elections are not staged on the same day in Finland and a dedicated municipal election campaign will be required. In other words, MPs will need to weigh up the costs (Blais 2006) and benefits of seeking a dual mandate.

One obvious cost is the extra workload and the reduced capacity efficiently to combine both mandates. Most MPs are members of between two and three Eduskunta committees with the voluminous ‘paperwork’ that entails. Moreover, whilst the Eduskunta does not convene on Mondays and MPs can, and mostly do, attend the plenary sessions of the municipal council, they cannot participate in the Wednesday meetings of the municipal council committees (lautakunnat) since the Eduskunta is then in session. An attendance register in short would reveal that MPs are conspicuous by their absence from the real decision-making organs of municipal government (Borg 2018b).

Indeed, over the years, opposition to the cumul has been voiced by a handful of parliamentarians—on essentially practical grounds—and a few academics—on constitutional grounds. A small minority of MPs has been concerned to avoid the ‘worst of both worlds’ syndrome. Thus, “properly to perform an MP’s duties means there is no time really to get to grips with decision-making in the economically struggling Salo municipality” (Pertti Hemmilä).Footnote 8 “As an MP I am engaged in national and international politics and they take up all my energy” (Katri Komi—Joroinen).Footnote 9 “It is impossible to combine the role of chair of a municipal council with being an MP” (Riitta Myller-Joensuu).Footnote 10 “I no longer have the time to combine both jobs and, anyway, municipal council debate has become punctuated by gratuitous personal attacks” (Katja Taimela-Salo).Footnote 11

As to the theoretical objection to the cumul, this has largely followed from the lack of a clear divide between the elected tiers of national and municipal government (Ryynänen 2009). According to this critique, the dual mandate has pointed up fundamental problems of institutional design in so far as the cumul involves a conflation of legislative and executive roles and a blurring of the separation of powers principle set out in Article 3 of the Finnish Constitution (Väänänen 1980). It can scarcely be considered desirable, the argument runs, for a municipal mandate-holder who is also an MP to be able in the latter role to influence the very legislation he/she is required to implement in the municipality (Ryynänen 2012). Such a potential conflict of interest could readily promote the endemic sotto voce cronyism associated with the heyday of the French cumul (Knapp 1991).

However, whilst the costs have been intermittently aired, what is far more striking has been the broad cross-party consensus favouring, or at least not challenging the Finnish cumul. This stands in contrast to France, where the practice was limited in 1985, and the Irish Republic, where in 2003 the dual mandate was abolished, albeit controversially. In the latter case, an initial attempt to proscribe the cumul was overthrown by four Independent members of the Dáil (TDs), who otherwise supported the government, along with a number of Fianna Fáil backbenchersFootnote 12 and when, under the Local Government (No. 2) Act 2003, the dual mandate was abolished, this led to a legal challenge from the Fine Gael TD Michael Ring.Footnote 13 The cumul has proved similarly controversial in Estonia where it was abolished in 2002 but then restored in 2017 (Saarts et al. 2021, p. 286).

In sum, the prevalent practice of the cumul in Finland has been broadly consensual, taking us back to our central question of why most Finnish MPs hold a dual mandate. Why, when applying a cost–benefit calculus, has the cumul been so heavily favoured by MPs over single office-holding? What can MPs hope to gain by ‘double jobbing’? In the next section, the incentive to cumulate is associated with the value of ‘localness’ as a PVEA in an electoral system motivating both intraparty and inter-party competition. At the same time, it is assumed that the relative value of localness will vary circumstantially—greater for some MPs than others.

Perspectives on MP ‘Localness’

Localness has informed several lines of inquiry in the comparative literature. Perhaps, the dominant strand has analysed the impact of MP localness on legislative performance (Sällberg and Hansen 2020). In France, for example, the cumul has been widely implicated in the weak legislative performance of National Assembly deputés when evaluated in terms of their attendance at plenaries and committee sessions (Navarro et al. 2012; Brouard et al. 2013; Daoulas 2021) although, plainly, absenteeism of this kind is not the only or necessarily the best measure of legislative efficiency (Hajek 2017; van der Voorde 2020; Van de Voorde and de Vet 2020). In the Irish Republic the conventional wisdom held that the legislative performance of Dáil TDs suffered because a strongly parochial orientation prioritised constituency service based on the dual mandate over work in parliament (Chubb 1957; Marsh 2007; Martin 2010). O’Leary (2011, p. 341) reported an interview with a Dáil TD who described how he spent only about 30% of his time on legislative work “because in order to be re-elected you need to spend time on constituency work”.

Localness has spawned a substantial body of research—from what might be described as the ‘friends-and-neighbours’ school of political geographers—analysing the impact of the physical distance to a candidate as the basis for the voting decision (Evans et al. 2017; Herron and Lynch 2019; Put 2021). Focussing on the 2015 British general election, for example, Evans et al. (2017, p. 63) note that, controlling for party preference and incumbency, we expect that (i) voters will be more likely to vote for a candidate who is closer to them geographically than one who is more distant and (ii) voters will be more likely to vote for a candidate whom they perceive as having a higher level of localness.

Localness has also been viewed as a party resource—the basis for candidate selection and the development of nomination strategies. In the Belgian flexible-list PR context, for example, Put et al. (2019) did not find any direct impact of candidate localness on the aggregate party list vote at the district level but they did find that the distribution of local candidates across many municipalities made a difference.

Finally, there is a literature on the value of localness as a candidate resource (Foucault 2006; François 2006). Drawing on the open-list electoral system in Estonia, Tavits (2010, p. 218) finds that candidates with prior local-level political experience (localness) are electorally more successful than those lacking this attribute and she adds (Tavits 2010, p. 230) that, in the context of intraparty candidate competition, local-level political experience serves the purpose of differentiating candidates from their co-partisans and attracting personal votes.

This paper also views the cumul des mandats from an essentially ‘candidate/MP resource’ perspective. The presumption is that the majority of Finnish parliamentarians are not first and foremost ‘office-seekers’ (Strøm 1990; Sandberg 2013); they do not seek municipal council office as a primary goal. Instead, they view municipal elections as a means of reinforcing their ‘localness’ either as a vote-earning attribute or as a way of enhancing their qualifications as ‘local MP’ for the municipality. This implies a difference between MPs both in terms of the electoral value they attach to a local connection and the importance of localness as a representational merit. Shugart et al. (2005, p. 441) have speculated that “the probability that a legislator exhibits any given PVEA increases with magnitude when the list is open and we expect these efforts to be stronger for first-term legislators than those with longer service”. Indeed, their suggestion that the value of localness would be expected to rise with (municipal) magnitude and be greater for new MPs than more experienced colleagues leads us nicely into a presentation of our hypotheses.

Hypotheses

In his work comparing electoral systems, Grofman (2005) distinguishes between a geographical constituency and a candidate’s electoral constituency, the latter defined by Arter (2021b) as “the territorial boundaries of a politician’s personal vote within the geographical constituency”. In the Finnish case, a politician’s primary electoral constituency (Arter 2021b) is his/her home municipality and hence the paramountcy of localness as a vote-maintenance mechanism. Particularly for first-term Finnish parliamentarians, who are statistically most at risk of an intraparty incumbency defeat, a municipal council seat will be likely to serve as a useful profiling exercise as well as a vehicle for core personal vote consolidation (Table 4).

In contrast, longer-serving legislators will have gained wider name-recognition (across the geographical constituency, if not beyond), will boast a record of service (‘pork’) delivery (cf. Cain et al. 1987; Erickson 1995), and there will be a reduced emphasis on personal vote maintenance in the municipality. There may well also develop a growing appreciation of the burden of combining mandates. Longer-serving MPs are also more likely to have plans to withdraw from politics at the next general election or to move to employment outside parliament. Our first formal hypothesis is thus:

Hypothesis 1

In the Finnish intraparty preference voting system the incentive to cumulate will be greatest for first-term parliamentarians and decline with legislative experience.

Recent work on open-list PR systems has deployed regression discontinuity design and paired contests between last-place ‘winners’ and best-place losers to estimate the extent of the (any) incumbency advantage. The results have been mixed. Dahlgaard (2016) found a sizeable incumbency advantage for marginally elected councillors in Danish municipal elections when standing for parties running open lists. However, when analysing Lower House elections in mixed-member Japan between 1996 and 2014, Ariga (2015) holds that “incumbents in multi-member constituencies where there is intraparty competition are more likely to have little advantage or even a disadvantage over non-incumbents of the same party”. In Finland the evidence suggests that last-place ‘winners’—or what Selb and Lütz (2015) describe as ‘at the edge candidates’—are statistically most likely to lose out to a strong co-partisan challenger. Over the 15 general elections between 1966 and 2019, just over two-fifths (42.1%) of intraparty incumbency defeats involved last-place winners. Our second formal hypothesis is thus:

Hypothesis 2

In the Finnish intraparty preference voting system the incentive to cumulate, will be greater for marginal incumbents than MPs gaining a higher list position at the last general election.

Prima facie, the value of localness and the incentive to hold a dual mandate would also be expected to reflect the size of the municipality. As Put and Maddens (2015) have noted, this is because however strong the candidate localness as a vote-earning attribute, if the municipal population size is small, the electoral impact in terms of individual preference votes at the constituency level will be smaller than in larger municipalities. Put another way, in the larger municipalities there will be more (potential) votes available and more council seats to be filled but, equally, more candidates—both inter-party and intraparty—competing to fill them. The prospective personal vote loss of not contesting municipal elections to one of the city councils, particularly for less experienced and/or marginal incumbents, may well be considerable. In the smaller municipalities there will be (often substantially) fewer votes available, fewer council seats to be filled and fewer candidates competing to fill them. Equally, the vote required for municipal office is likely to be relatively small and unlikely to jeopardise an incumbent parliamentarian’s general election prospects, particularly if he/she is an established politician with a secure personal vote across the district. Indeed, if and when a long-serving MP routinely contests elections in municipalities where perhaps less than 100 votes will top the list of all candidates, this would seem to favour an interpretation of localness as a representational rather than electoral attribute—that is, primarily designed to demonstrate a continuing concern to be seen as ‘the local MP’. Our third formal hypothesis runs:

Hypothesis 3

In the Finnish intraparty preference voting system the incentive to cumul, will be greater in larger municipalities than smaller ones.

Non-cumulating MPs

By no means all Finnish parliamentarians hold a dual mandate. Of those MPs elected at the four general elections between 2007 and 2019 (n = 796), an average of 16.8% (n = 134) did not seek a dual mandate at the following municipal election and over two-fifths of these (40.3%, n = 54) were MPs with no record of dual mandate-holding over the duration of their current legislative incumbency. This raises the pertinent question of possible disincentives to cumulate and the type of candidate characteristics the might militate against the cumul.

Whilst our emphasis has been on the value of the local connection, localness is only one of a multitude of possible PVEAs. These can range from the standard demographic variables of gender, age and occupation to attracting a niche electorate on the basis of a fundamentalist faith (Pentecostalism, Free Church membership, etc.) or being known as a recent ‘reality show’ contestant. Carey and Shugart (1995, p. 419) have noted that “the national celebrity enjoyed by movie stars or athletes can translate into valuable personal reputation in some electoral systems”. The Finnish open-list PR voting system is a case in point (Arter 2014). Marsh et al. (2010, p. 324) have referred to the ‘high celebrity density of politics’ in Finland. Over the years celebrity candidates, used strategically by political parties, have generally attracted a substantial personal vote and so, too, those members of parliament who become celebrity politicians (Street 2012), recognisable to a broad public by dint of the media coverage they attract and/or the message they communicate. National celebrity (‘nationalness’) is, of course, the antithesis of localness as a candidate attribute and may serve as a powerful disincentive to hold a dual mandate. Equally, this may not prevent an elected celebrity from subsequently seeking to ‘cumulate’ either at the behest of the party or because of a belief that a local grounding is what is expected of a Finnish MP. Our final hypothesis runs thus:

Hypothesis 4

In the Finnish intraparty preference voting system, the incentive to cumulate will be reduced when national celebrity trumps localness as the primary vote-earning attribute.

Methods and results

Our analysis uses register data for serving members of parliament at the time of the 2008, 2012, 2017 and 2021 municipal elections (with the exception of the single MP for the Autonomous Åland Islands). Statistics Finland produces official statistics for both general and municipal elections, as well as population statistics, and these data are the main source of information (https://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/). To account for mid-term changes in the composition of parliament—that is, to identify those MPs who were (still) in the office at the time of municipal elections—we consulted the public website of the Finnish Parliament (https: //www.eduskunta.fi/). Data on celebrity status, gender, and the age of MPs draw on the authors’ database on the personal characteristics of legislators. Descriptive statistics are provided in the “Appendix”.

Our basic assumption, reflected in the hypotheses, has been that the relative value of localness and by extension the incentive to cumulate, will vary circumstantially, being greater for some MPs than others. The dependent variable, therefore, is a binary outcome that distinguishes those MPs who ran for municipal office and won a dual mandate (coded 1) from those who did not (coded 0).

A series of independent variables are used in testing the hypotheses. Number of terms refers to the length of current legislative incumbency, a continuous variable that varies between 1 and 12 consecutive terms. We control for returnee, that is, an MP who had returned to the Eduskunta after a period out of it. Electoral insecurity is a continuous variable that measures the distance to the last-place ‘winner’ on the party list at the previous general election. The variable runs from one (last-place ‘winner’) to eleven (the MP that won more intraparty votes than ten elected co-partisans). Politicians who filled seats that fell vacant between general elections are also coded as 1 for electoral security. A dummy variable, mid-term MP, is included to control for these politicians.

Population refers to the resident population of the municipality. The measure is highly skewed to the left and therefore it is log transformed using the natural logarithm to achieve a normal distribution. To account for the possibility that the relationship is curvilinear, the squared term of municipal magnitude is added. National celebrity indicates an alternative PVEA which is expected to diminish the inclination to seek a dual mandate. These MPs were household-name politicians at the time of the municipal election in question.Footnote 14 Finally, two socio-demographic variables are included. Woman is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the candidate is a woman and 0 otherwise. Age (grand mean centred) is introduced as a continuous variable. Election year is included as a fixed effect to account for differences in the dependent variable due to unobserved changes in MPs behaviour over time.

Multilevel logistic regression analysis is employed (i) because the outcome variable is binary (yes/no) and (ii) to account for the dependency of data. In respect of the latter, multilevel modelling accounts for the clustering of observations. Such a modelling strategy allows us to obtain more accurate and conservative standard errors and p values. Hence, we have repeated measurements since many of the MPs (40%) have participated in more than one municipality election. Longitudinal data can be viewed as clustered: data collection events (elections 1, 2, 3, etc.) are nested within individual MPs (level 2). These individuals are further nested within municipalities (level 3).

Table 5 sets out the results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis. We first estimate an empty model which only includes random intercepts and no predictors. The variance components in the random effects part reveal that the incidence of the cumul does vary between different municipalities (level 3) and between MPs (level 2). It is therefore relevant to account for clustered data. In multilevel logistic regression, it is not possible directly to compare the way the variance components change because the lowest-level residual variance and the higher-level variance are rescaled from one model to another. In Model 1, we include the candidate and municipality characteristics. The between-municipality variance becomes 0, which indicates there is no more between-municipality variation left to explain. On the other hand, variation between candidates remains.

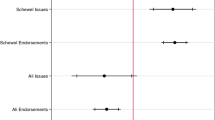

Next we test the hypothesis relating the incentive to cumul to the length of current legislative incumbency. So as to facilitate the interpretation of the results, we also present average predictive margins in Fig. 1, based on the estimates in Table 5. Average predictive margins refer to the expect values of the dependent variable at different levels of each independent variable whilst controlling for the effects of the other independent variables.

H1 predicted that the electoral incentive to cumulate would be the greatest for first-term parliamentarians and decline with legislative experience. All in all, there is strong support for this first hypothesis. The effect is statistically and substantially significant according to the logistic regression coefficient. The incidence of dual mandate-holding is predicted to decrease about 4 percentage points for each additional term, all other things being equal. Figure 1 shows that the incidence decreases from 87 to 60% as we go from first-term to seventh-term MPs (due to very wide confidence intervals, the predicted scores for the range 8–12 are not displayed in the graph).

Consonant with H2, the incentive to cumulate is also greater for marginal incumbents than MPs finishing in a higher list position courtesy of a greater number of preference votes at the previous general election. We expected that the incidence of the cumul would decrease as the value of the electoral security variable increased (that is, greater distance to the last-place ‘winner’). The coefficient is not as high as above, but still the effect is substantial. Translating the estimated logit coefficient into probability differences demonstrates that the prevalence of the dual mandate decreases from 84 to 69% as the electoral security variable increases from 1 to 7 points (the maximum value is 11).

Regarding H3, the incidence of the cumul is affected by municipal magnitude, although the relationship is curvilinear. Hence, the data do not entirely confirm the expectation that the incentive to cumul would be greater in larger than smaller municipalities. In fact, the largest and smallest municipalities register the lowest scores for the dependent variable. MPs in medium-sized municipalities are predicted to have sought a dual mandate—85% at the vertex of the curve. This is considerably higher than those in the largest and smallest municipalities where around 70% are predicted to have done so. The confidence interval is wide in the lower range of the variable which implies a high level of uncertainty. Note, however, that since the population variable was log transformed, the interpretation is not in the original unit. The predictive margins seen in Fig. 1 suggest that the highest predicted score is for municipalities with about 30,000 inhabitants. Upon closer inspection, the bivariate relationship between untransformed population size and the outcome variable is indeed curvilinear (the result of locally weighted scatterplot smoothing not reported in any figure). The highest incidence of the cumul is for MPs who lived in a municipality with a population between 55,000 and 85,000.

Finally, national celebrity appears to trump localness. In line with H4, the incentive to cumulate is significantly lower among politicians with celebrity status (see Table 5). Only 62% of the celebrity politicians sought a dual mandate, compared to 82% among the remaining MPs. However, since there were relatively few celebrities, 54 MPs with 64 election observations in the whole sample, the standard error for the estimate is quite large. This is also apparent in Fig. 1 where the confidence interval is wide. Whilst gender is an insignificant predictor, there is a tendency for the incidence of dual mandate-holding to decrease with an MP’s age.

Concluding remarks

We started with the basic question of why the vast majority of Finnish MPs hold a dual mandate and, proceeding from an ‘MP resource’ perspective, tied localness and the incentive to ‘cumulate’ to (i) the value of a dual mandate as a PVEA and (ii) its value as a representational merit, strengthening the legislator’s claim to be considered the local MP. Drawing on the four municipal elections between 2008 and 2021, we tested hypotheses linking the incentive to hold a municipal council seat to (i) the length of an MP’s present term in parliament; (ii) the extent of his/her electoral marginality at the last general election; and (iii) variable municipal magnitude. The results show (H1) that the incentive to cultivate a municipal mandate is greatest among first-term parliamentarians and declines with the length of legislative incumbency and that (H2) the incentive to cumulate is greater for marginal incumbents than MPs gaining a higher list position on the basis of personal preference votes at the previous general election. However, contrary to the expectation (H3) that the incentive to cumulate would rise with municipal magnitude, the incidence of dual mandate-holding was lowest in the largest cities. This might well be linked to the higher proportion of celebrity and household-name politicians—cabinet ministers, party chairs and the like—who view a city council seat as neither a realistic nor a necessary option. Note here that the capital Helsinki serves as a constituency for both general and municipal elections.

Overall the evidence points to the way the pathway to parliament in Finland has run via a municipal council and the road to remaining in parliament has run via a municipal council—something that is particularly striking among first-term MPs. Of those MPs (n = 276) elected to serve a first legislative term over the four Finnish general elections between 2007 and 2019, an average of 81.5% held a municipal council seat prior to becoming an MP. In other words, they assumed a dual mandate on their elevation to the Eduskunta. Becoming a dual mandate-holder on first election to parliament does not, of course, establish an incentive for retaining a cumul thereafter, especially in light of the extra workload involved as members of parliamentary committees. Significantly, however, the incidence of the cumul rose markedly among first-term MPs at the first municipal election following their ‘promotion’ to parliament. Over the four municipal elections between 2008 and 2021, the proportion of first-term MPs gaining a municipal council seat increased by an average of 9.4 percentage points. In short, not only did an overwhelming majority of first-term MPs retain a dual mandate but in the order of 1 in 10 became dual mandate-holders for the first time subsequent to their first election to parliament.

True, the incentive to cumulate (our focus) does not account for an individual politician’s motivation for doing so. However, prima facie the case for viewing the cumul as a PVEA would appear strongest among new and electorally vulnerable MPs in large-municipality party strongholds where the intraparty competition for votes is likely to be most intense. As a random example, co-partisan competition between two first-term MPs—the last-place ‘winner’ and the next-to-last-place incumbent—on the Green Party list for Helsinki at the 2017 municipal election resulted in votes that exceeded their personal tallies at the general election 2 years earlier.

In contrast, a persuasive case for viewing dual mandate-holding as a representational resource, more than an electoral imperative, could be made in the way long-serving ‘safe seat’ MPs sit on municipal councils when the electoral increment from doing so appears modest at best. Not untypically, Jari Leppä (presently minister of agriculture), who was elected for a sixth consecutive parliamentary term with the highest personal poll on the Centre Party list for the Kaakkois-Suomi electoral district at the 2019 general election, ran for the Pertunmaa Municipal Council 2 years later (as he had in the five previous contests), heading all the other candidates with 88 votes. This was only 1.2% of his personal vote in Kaakkois-Suomi in 2019 and plainly would in practice have no effect on his parliamentary re-election prospects. Rather, Leppä, like the majority of Finnish MPs, has a background in local politics and localness, when taken in association with partyness, is viewed as an important representational asset. It is also clearly hard for MPs with say 20 years of experience on the municipal council to detach themselves from local politics whilst serving as members of parliament which is a further reason they continue to run in local elections and claim a municipal mandate. Local politics is in the blood.

The least likely to ‘cumulate’, aside from those planning to retire or move to positions outside parliament, are MPs elected as celebrity candidates and those serving MPs who become household names by dint of the coverage they receive in the media (for professional and/or private-life reasons). It is not uncommon for strategic electoral reasons for parties to shift ‘heavyweight’, strong-vote-earning politicians with a national ‘name’ from an up-country constituency to a populous electoral district in the ‘deep south’ (Uusimaa and Helsinki) where they will have no local roots and will not seek municipal office. These are ‘carpetbaggers’ for whom the value of localness is at best of secondary importance. Some MPs elected as celebrity candidates do seek a municipal mandate—the ‘soap actor’ Risto Autio in the 2008 municipal election is a case in point. But many do not.

In sum, localness and the concomitant cumul-holding in Finland is not all about electoral incentives and personal vote-earning. It is at least as much to do with the representational focus of legislators and the expectation of party selectorates and voters alike that MPs will promote and protect the interests of a particular municipality. It is all about area representation in parliament. Indeed, some MPs even describe themselves as ‘MP for Porvoo’ or ‘MP for Pedersöre’ (or wherever). Tellingly, veteran MPs who do not need to hold a dual mandate as an electoral resource, do so to affirm their commitment to representing their ‘home municipality’. At heart Finns are local MPs.

Indeed, viewing Finnish MPs as local MPs brings out a wider point. In multi-member PR electoral districts with a magnitude ranging from 7 (Lapland) to 36 (Uusimaa in the hinterland of Helsinki), Finnish legislators do ‘municipal service’ in much the way British MPs do constituency service in single-member districts. For Finnish MPs their primary electoral constituency is the municipality from where they derive their core personal vote. Finnish MPs do not hold weekly ‘surgeries’ in the manner of their British counterparts or stage Irish-style ‘clinics’ and they do not have offices in the Town Hall like most French deputés. Unlike say Canada, moreover, relatively few of their personal assistants are based ‘in the field’. Yet, the territorial dimension of representation is paramount in Finland. In Norway and Sweden, the historic importance of geographical representation is symbolically reflected in the regional seating of parliamentarians. In Finland it is reflected not only in the high incidence of the cumul but, as significantly, the broad cross-party consensus surrounding the practice.

As a postscript, in January 2022, elections were held to a new intermediate tier of government based on the historic Finnish counties—that is, to 21 so-called ‘welfare districts’ (hyvinvointialueet), charged with the administration of health care and the social services. Following these elections, approaching three-fifths of (eligible) parliamentarians held a triple mandate (parliamentary, municipal and county), among them ministers and party leaders. When nearly 90% of MPs hold dual mandate and almost 58% a triple mandate,Footnote 15 the scale of the Finnish cumul can only be viewed as exceptional in comparative perspective.

Notes

Päivi Rautanen, ‘Anneli Jäätteenmäki tekee paluun politiikkaan’ – pyrkii kotikaupunkinsa valtuustoon Lapualla’ YLE 10.3.2021. Jyri Hänninen, ‘Vanhanen on ehtinyt myös valtuustoon’ Helsingin Sanomat 23.7.2008.

Annu Perälä, ‘Kansanedustajien vaalirysä. Uutissuomalainen: Ainakin 174 kansanedustajaa on lähdössä kuntavaaliehdokkaaksi’ Helsingin Sanomat 6.3.2021.

Only the foreign minister did not seek a dual mandate. Of those serving government ministers who were members of parliament at the time of the four municipal elections between 2008 and 2021 (n = 68), 79.4% held a dual mandate.

Communication from Kersten Kattai 23.11.2021.

From the earliest years of Finnish independence the pathway to the Eduskunta has typically been via a seat on the municipal council. Thus, prior to the 1924 general election, the municipality of Ruokolahti in the East Viipuri constituency had not had its ‘own MP’ or even a local candidate on the Agrarian Party’s district list. However, with the general election in mind, the local branch of Inkilanmäki and Virmutjoki canvassed the case of Anttoni Vertanen, a local farmer, director of the local fire service and a senior member of the municipal council. The Agrarians’ municipal party association in Ruokolahti co-ordinated Vertanen’s campaign and nominated a number of ‘election whips’ (vaalipiiskurit) to mobilise the party vote. Vertanen was duly elected (Mylly 1989, pp. 340–342).

In the 1918–1919 municipal elections, the SDP won a majority of seats on the Viipuri rural district council (Soikkanen 1970, p. 354) and despite their depleted ranks (many Red activists were executed or imprisoned), the SDP gained over one-third of the national municipal vote and even won a majority in the Red stronghold of Tampere.

Kansanedustajat ehdolle kuntavaaleihin. Yle 13.8.2012.

Hannu Vähämäki, Elomaa ja Hemmilä eivät mieli valtuustoon. YLE 17.9.2012.

Satu Haapanen, Katri Komi: Eiköhän keskusta pikkuhiljaa opi oppositiopolitiikkaa. YLE 3.9.2012.

Riitta Myller jättää Joensuun valtuuston puheenjohtajajuuden. YLE 21.11.2011.

Tarja Hiltunen, Katja Taimela ei lähde ehdolle kuntavaaleihin Salossa- kansanedustajien työltä ei jää aikaa. YLE 16.2.2021.

Aidan O’Connor, Politicians on their marks as the end of the dual mandate looms. The Kerryman 14.2.2003.

Dual mandate madness. The Irish Times 28.2.2003.

Three types of national celebrities may be identified: (i) high-profile serving ministers holding a strategic government portfolio (prime minister, foreign minister, finance minister) often in conjunction with the post of party chair; (ii) MPs elected as ‘celebrity candidates’ from outside the world of politics—sport, entertainment, arts the media—at the general election before the municipal election in question and (iii) rank-and-file MPs who became national-newsworthy at the time of the municipal election in question for ad hoc reasons, inter alia a recent presidential candidacy participation in a popular television ‘show’ or simply the expression of provocative and widely-reported views.

N = 174. Elections were not held in Åland or Helsinki. The capital city is responsible for its own social and health care provision.

References

Ariga, K. 2015. Incumbency Disadvantage Under Electoral Rules with Intraparty Competition: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Politics 77 (3): 874–887.

Arter, D. 2014. Clowns, ‘Alluring Ducks’ and ‘Miss Finland 2009’; The Value of Celebrity Candidates in an Open-List Voting System. Representation 50 (4): 453–470.

Arter, D. 2021a. Digging in the ‘Secret Garden of Politics’: The Institutionalisation and De-instutionalisation of Membership Ballots in the Selection of Finnish Parliamentary Candidates. Scandinavian Political Studies 44 (3): 346–348.

Arter, D. 2021b. ‘It’s a Long Way from Kuusamo to Kuhmo’: Mapping Candidates’ Electoral Constituencies in the Finnish Open-List Single Preference Voting System. Political Studies Review 19 (3): 334–354.

Blais, A. 2006. The Causes and Consequences of the Cumul des Mandats. French Politics 4: 266–268.

Borg, S. 2018a. Kunnallisvaalitutkimus 2017. Keuruu: Otava.

Borg, S. 2018b. Aktiivisuus rekisteri tarpeen. Kuntalehti 7 (6): 2018.

Borg, S., and S. Pikkala. 2017. Kuntavaalitrendit. Helsinki: Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön julkaisu.

Brouard, S., O. Costa, E. Kerrouche, and T. Schnatterer. 2013. Why Do French MPs Focus More on Constituency Work than on Parliamentary Work? The Journal of Legislative Studies 19 (2): 141–159.

Cain, B., J. Ferejohn, and M. Fiorina. 1987. The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Carey, J.M., and M.S. Shugart. 1995. Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: A Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas. Electoral Studies 14 (4): 417–439.

Cheibub, J.A., and G. Sin. 2020. Preference Votes and Intraparty Competition in Open-List PR Systems. Journal of Theoretical Politics 32 (1): 70–95.

Chubb, B. 1957. The Independent Member in Ireland. Political Studies V (2): 131–139.

Crisp, B.F., K.M. Jensen, and Y. Shomer. 2007. Magnitude and Vote-Seeking. Electoral Studies 26: 727–734.

Crisp, B.F., B. Schneider, A. Catalinac, and T. Muraoka. 2021. Capturing Vote-Seeking Incentives and the Cultivation of a Personal and Party Vote. Electoral Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102369.

Dahlgaard, J.O. 2016. You Just Made It. Individual Incumbency Advantage Under Proportional Representation. Electoral Studies 44: 319–328.

Daoulas, J.-B. 2021. Cumul des mandats: Le poison devenu remède. Libération 30 (7): 2021.

Dodeigne, J., and J.-B. Pilet. 2019. Centralized or Decentralized Personalization? Measuring Intraparty Competition in Open and Flexible List PR Systems. Party Politics 27 (2): 234–245.

Erickson, S.C. 1995. The Entrenching of Incumbency: Re-election in the US House of Representatives 1970–1994. Cato Journal 14 (3): 397–420.

Esaiasson, P., and S. Holmberg. 1996. Representation from Above. Aldershot: Dartmouth.

Evans, J., K. Arzheimer, R. Campbell, and P. Cowley. 2017. Candidate Localness and Voter Choice in the 2015 General Election in England. Political Geography 59: 61–71.

Foucault, M. 2006. How Useful is the Cumul des Mandats for Being Re-elected? Empirical Evidence from the 1997 French Legislative Elections. French Politics 4: 292–311.

François, A. 2006. Testing the ‘Baobab Tree’ Hypothesis: The Cumul des Mandats as a Way of Obtaining More Political Resources and Limiting Electoral Competition. French Politics 4: 269–291.

Gallagher, M. 2008. Ireland: The Discreet Charm of PR-STV. In The Politics of Electoral Systems, ed. M. Gallagher and P. Mitchell, 511–532. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grofman, B. 2005. Comparisons Among Electoral Systems: Distinguishing Between Localism and Candidate-Centred Politics. Electoral Systems 24: 735–740.

Hajek, L. 2017. The Effect of Multiple-Office Holding on the Parliamentary Activity of MPs in the Czech Republic. The Journal of Legislative Studies 23 (4): 484–507.

Herron, E.S., and M.S. Lynch. 2019. ‘Friends and Neighbors’ Voting Under Mixed-Member Majoritarian Electoral Systems: Evidence from Lithuania. Representation 55 (1): 81–99.

Iivari, U. 2007. Kansanvallan puolustajat. Helsinki: Otava.

Karlsson, D. 2018a. Finns det ett kommunparti i riksdagen? In Folkets främsta företrädare, ed. D. Karlsson, 151–170. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

Karlsson, D. 2018b. Putting Party First: Swedish MPs and Their Constituencies. Representation 54 (1): 87–102.

Katz, R.S. 1985. Preference Voting in Italy: Votes of Opinion, Belonging and Exchange. Comparative Political Studies 18 (2): 229–249.

Katz, R.S., and L. Bardi. 1980. Preference Voting and Turnover in Italian Parliamentary Elections. American Journal of Political Science 24 (1): 97–114.

Knapp, A. 1991. The cumul des mandats: Local Power and Political Parties in France. West European Politics 14 (1): 18–40.

Lindman, S. 1968. Eduskunnan aseman muuttuminen 1917–1919. Suomen kansanedustuslaitoksen historia V1. Helsinki: Valtion painatuskeskus.

Marsh, M. 2007. Candidates or Parties? Objects of Electoral Choice in Ireland. Party Politics 14 (4): 500–527.

Marsh, D., P. ‘t Hart, and K. Tindall. 2010. Celebrity Politics: The Politics of Late Modernity. Political Studies Review 8: 322–340.

Martin, S. 2010. Electoral Rewards for Personal Vote Cultivation Under PR-STV. West European Politics 33 (2): 369–380.

Mylly J. 1989. Maalaisliitto 1918–1939. Maalaisliitto-keskustapuoleen historia 2. Helsinki: Kirjayhtymä.

Navarro, J., N.G. Vaillant, and F.-C. Wolff. 2012. Measuring Parliamentary Effectiveness in the French National Assembly. Revue Française de Science Politique. 62 (4): 611–636.

O’Leary, E. 2011. The Constituency Orientation of Modern TDs. Irish Political Studies 26 (3): 329–343.

Passarelli, G. 2020. Preference Voting Systems Influence on Intra-party Competition and Voting Behaviour. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Put, G.-J. 2021. Is There a Friends-and-Neighbours Effect for Party Leaders? Electoral Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102338.

Put, G.-J., and B. Maddens. 2015. The Effect of Municipality Size and Local Office on the Electoral Success of Belgian/Flemish Election Candidates: A Multi-level Analysis. Government and Opposition 50 (4): 607–628.

Put, G.-J., J. Smulders, and B. Maddens. 2019. How Local Vote-Earning Attributes Affect the Aggregate Party Vote Share: Evidence from the Belgian Flexible-List PR System. Politics 39 (4): 464–479.

Ryynänen, A. 2009. Eduskunta ja kunnallinen itsehallinto. Eduskunnan tulevaisuusvaliokunnan julkaisu 3/2009. Helsinki: Eduskunta.

Ryynänen, A. 2012. Kansanedustajien kaksoisroolit kuntapäättäjinä ovat ongelmallisia. Kuntalehti 30 (4): 2012.

Saarts, T., G. Sootla, and K. Kattai. 2021. Estonia—The Consolidation of Partisan Politics in a Small Country with Small Municipalities. In Routledge Handbook of Local Elections and Voting in Europe, ed. U. Kjaer, K. Steyvers and A. Gendzwill: 282–292. New York: Routledge.

Sällberg, Y., and M.E. Hansen. 2020. Analysing the Importance of Localness for MP Campaigning and Legislative Performance. Representation 56 (2): 215–227.

Sandberg, S. 2013. Cumul des mandats the Finnish Way. The Anatomy of Multiple-Office Holding Among Members of the Finnish Eduskunta 2000–2012. In Paper Delivered at the Norkom Conference 2013.

Selb, P., and G. Lütz. 2015. Lone Fighters: Intraparty Competition, Interparty Competition and Candidates’ Vote-Seeking Efforts in Open-Ballot PR Elections. Electoral Studies 39: 329–337.

Shugart, M.S. 2008. Comparative Electoral Systems Research: The Maturation of a Field and New Challenges Ahead. In The Politics of Electoral Systems, ed. M. Gallagher and P. Mitchell, 25–55. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shugart, M.S., M.E. Valdini, and K. Suominen. 2005. Looking for Locals: Voter Information Demands and Personal Vore-Earning Attributes of Legislators under Proportional Representation. American Journal of Political Science 49 (2): 437–449.

Soikkanen, H. 1970. Luovutetun karjalan työväenliikkeen historia. Helsinki: Tammi.

Street, J. 2012. Do Celebrity Politics and Celebrity Politicians Matter? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 14: 346–356.

Strøm, K. 1990. Minority Government and Majority Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tavits, M. 2010. Effect of Local Tier on Electoral Success and Parliamentary Behaviour. Party Politics 16 (2): 215–235.

Väänänen, P. 1980. Kansanedustajan Kunnallispoliittinen Profiili. Kanava 7: 411–416.

Van de Voorde, N. 2019. Does Multiple Office-Holding Generate an Electoral Bonus? Evidence from Belgian National and Local Elections. West European Politics 42 (1): 133–155.

Van de Voorde, N. 2020. Municipal Councillors in Parliament, a Handicap for Legislative Activism? Parliamentary Productivity of Dual Mandate-Holders in the Belgian Federal Assembly Between 1995 and 2014. Parliamentary Affairs 73 (3): 565–585.

Van de Voorde, N., and B. de Vet. 2020. Is All Politics Indeed Local? A Comparative Study of Dual Mandate-Holders’ Role Attitudes and Behaviours in Parliament. Swiss Political Science Review 26 (1): 51–72.

Villodres, C.O. 2003. Intra-party Competition Under Preference List Systems: The Case of Finland. Representation 22 (3): 55–66.

Acknowledgements

Söderlund has been funded by the Research Project “Intraparty competition: the neglected dimension of party competition” funded by the Academy of Finland (Project Number 316239).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There was no conflict of interest involved in the generation of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Descriptive statistics

Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Incentive to cumulate | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

Number of terms | 2.43 | 1.82 | 1 | 12 |

Returnee | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 |

Electoral security | 2.41 | 1.73 | 1 | 11 |

Mid-term MP | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0 | 1 |

Population (ln) | 11.02 | 1.56 | 6.92 | 13.40 |

Celebrity status | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0 | 1 |

Woman | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

Age | 49.21 | 10.94 | 26 | 76 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arter, D., Söderlund, P. When even the prime minister sits on the municipal council. Analysing the value of ‘localness’ and Finnish MPs’ incentives to ‘cumulate’ in an open-list voting system. Acta Polit 58, 79–100 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00234-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00234-x