Abstract

During the European debt crisis, there has been a massive political debate between the EU institutions and the governments of crisis countries on the kind of austerity measures these countries have to accept in order to receive financial assistance from rescue funds established by EU and IMF. Based on a Weberian approach regarding solidarity as an act of mutual help, we interpret austerity measures as particular conditions of solidarity Alter has to agree to in order to receive assistance from Ego. In this paper, we ask to what extent citizens of EU countries agree on the notion of conditioned solidarity, and to which extent they are divided by socio-structural or cultural conflict lines, or by country particularities. Using unique data from the 2016 13 country ‘Transnational European Solidarity Survey’, findings show that the majority of respondents reject the idea of conditionality. Logistic regressions reveal rather weak attitudinal differences between respondents at the individual level, while at the country level respondents from countries with growing unemployment, higher unemployment rates, government debt, and poverty rates are in tendency more likely to reject the measures. We conclude that paying attention to the idea of conditionality is an important aspect of assistance measures in the future, if political actors look to avoid a lack of legitimacy among European citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the Euro and sovereign debt crises, the European Union (EU) has experienced one of the most problematic periods since its inception. Following the financial crisis starting in 2008 and the subsequent economic crisis, several Member States of the Eurozone had been faced with severe public debt overload by trying to stabilize their national banking systems. In order to avoid a collapse of the common currency, the European Commission, European Central Bank, and International Monetary Fund made enormous financial resources available to debt-ridden Member States (Dyson 2017) to stabilize their economies and to keep the Eurozone stable by granting financial support.Footnote 1 Thus, Eurozone countries have made enormous financial resources available to debt-ridden crisis countries, with these loans and guarantees leading to a hitherto unseen degree of intra-European redistribution. One can expect that the crisis has fostered a previously unseen extent of ‘fiscal solidarity’ (Lengfeld et al. 2020).

However, each bailout programme contained a set of political conditions, so-called austerity measures, which had to be implemented by the respective governments. Although these measures should ensure that the national economies would recover and the confidence in their markets would be renewed, it even fostered an economic downturn in the short term, especially in the crisis-stricken Mediterranean Member States, where welfare state systems have been comparatively weak even before the crisis (e.g. Gelissen 2000). In particular, austerity measures affected the most vulnerable groups in society, including the poor, the sick, the unemployed, and the elderly (Callan et al. 2011). Looking back, the crisis years of 2012 to 2015 show that it was first and foremost these austerity measures and not the introduction of the financial rescue funds per se nor the size of the credits made available which had been the most controversial part of the conflict within and among crisis countries.

In this paper, we examine what EU citizens think about these austerity measures. Relying on a Weberian understanding of solidarity, we propose the term ‘conditioned solidarity’ to express that Ego may expect that providing support to Alter should be dependent on Alter’s agreement to meet particular obligations or patterns of behaviour. According to the sovereign debt crisis, this seems to be especially true to Ego’s expectations that crisis countries must push themselves in order to get back on their feet in the long run, i.e. by reducing public spending or raising public revenues. We thus ask to which extend EU citizens expect acts of fiscal solidarity—providing financial assistance to crisis countries—being conditioned by particular austerities? Furthermore, we aim to investigate how much citizens are divided over austerities, as austerities may be regarded as a political minefield on which the expectations of citizens from different socio-structural and cultural groups as well as countries may clash. Our understanding is, the more divided social groups or countries are over conditions of assistance, the more complicated political negotiations on financial rescue packages between the EU and governments of Member States will be in the future.

Thereby, this paper aims at contributing to the ongoing academic debate on European solidarity in extending knowledge on the fundamental nature of fiscal assistance as an act of mutual aid by exploring expectations and refusal of the idea of conditionality. Regarding the latter, we furthermore want to inform the public debate as it sheds light on the question whether the resistance is a topic of specific groups being able to mobilize effectively, or whether denial is a phenomenon of whole societies. Finally, we want to highlight which of the particular austerity measures are being met with opposition or being requested by citizens. This knowledge can help to more appropriately select conditions in comparable scenarios in the future, not only in regard to their efficiency and effectiveness but also their acceptance among the public to not burdening the social bond within and among European societies.

In the section “Conditioned solidarity”, we propose a concept of conditioned solidarity and apply it to the debate on austerity measures. The “State of research” section shows that while recent studies primarily investigated Europeans general attitudes towards transnational financial bailout and the causes of opposition against it, little is known about the acceptance of specific austerity measures and the reasons for citizen’s support or opposition. In the “Divided over austerities?” section, we thus formulate hypotheses on why people may be divided over austerities. These hypotheses are tested using data from the ‘Transnational European Solidarity Survey’ carried out in 13 EU Member States in 2016 (“Data and methods” section). This survey contains items on acceptance towards four different austerity measures crisis-affected countries have to implement in order to receive financial aid from the EU: increase of national value added tax, social spending cuts, increase of retirement age, and reduction of the work force in the public sector. Results show that except for reducing public employees, the majority of respondents disapprove the idea of conditionality (“Results” section). Using regression analyses, we find that people with a higher social status, holding leftist political attitudes, a European or a national identity, are more in favour of conditionality than lower status persons, the politically centrists and rightists, and those not holding a European or national identity. However, the differences are rather weak and not statistically significant in most cases. Important differences are observed between countries which can be traced back to the experience of collective vulnerability: respondents living in countries with growing unemployment, higher unemployment rates, government debt, and poverty rates are somewhat more likely to refuse austerity measures. The “Conclusion” section is dedicated to conclusions about the future of financial assistance measures and the potential reactions of citizens towards austerities.

Conditioned solidarity

A variety of different types of solidarity has been referred to in the wake of the European crises since 2008 (e.g. Koos 2019). As the term solidarity itself can have multiple meanings, it is frequently used as a rather vague, often politicized, and normative concept. In this paper, we follow a Weberian perspective on solidarity recently proposed by Gerhards et al. (2019, p. 18ff.). In line with Max Weber’s idea of intended social actions (Weber 1968), they regard solidarity as a form of social behaviour when Ego intends to voluntarily support Alter who is in a situation of need—a solidaric action (Gerhards et al. 2019, p. 19). Despite this, authors keep the definition of solidarity away from the question as to which factors determine its existence. We think this perspective is a helpful starting point as it allows a more widespread description and characterization of such acts regarding scope, motivation of acting, or character of the relationship.

One important aspect of solidaric actions is the particular conditions Alter has to fulfil to receive support expected or explicitly claimed by Ego. Here, welfare state research has provided huge evidence for the conditionality of financial acts of solidarity (Buß et al. 2017; Carriero and Filandri 2019; Larsen 2008; Oorschot 2000; Oorschot and Roosma 2017). These studies reveal different deservingness criteria acknowledged by citizens, differences in beliefs towards conditions applied to the provision of financial help, and factors explaining these differences in the people’s views. Recent research on European unemployment risk sharing also shows that such measures are more likely to be accepted if countries are obliged to introduce education and training systems for the unemployed as a condition (Kuhn et al. 2020, p. 220; Vandenbroucke et al. 2018).

Although we are not able to review this research on welfare state solidarity in detail, we pick up the idea that willingness for welfare state run assistance to people relies on perceptions of conditionality, and will apply this idea to financial solidarity provided to countries. In case of European fiscal solidarity, the bailout assistance measures introduced in several countries were all accompanied by a set of conditions for the receivers aimed at improving the financial situation of the countries, usually referred to as austerity measures or austerities. The relationship between citizens and institutions of debtor and donor countries seems to have worsened as a result from differing expectations and demands by the recipients and donors. In some receiving countries, the conditions implied resulted in severe public protest. In Portugal and Greece, the public sphere was paralysed by general strikes called in response to austerity measures in public sector employment (Bugge and Khalip 2013; Rüdig and Karyotis 2013). Moreover, the Greek government was heavily trying to ward off financial constraints to their national social policy, tax system, and the public employment sector. In his popular book, the former Minister of Finance Yanis Varoufakis, who was responsible for negotiating the measures for the Greek government, wrote: ‘Austerity is a morality play pressed into the service of legitimizing cynical wealth transfers from the have-nots to the haves during times of crisis, in which debtors are sinners who must be made to pay for their misdeeds’ (Varoufakis 2017, p. 40). However, protest also emerged in donor countries. In 2011, the Slovakian parliament refused to increase their country’s guarantees for the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) fund (Kulish and Castle 2011). A year later, Finland publicly announced that their solidarity with countries impacted by the crisis would have limitations and managed to negotiate special conditions ensuring that they would retain their deposits in case of credit failure (SPIEGEL Online 2012). Taken together, beside the size of the assistance measures, the conditions accompanying them have proven to be a big restraint for support for further durable measures of social integration among Europeans.

State of research

After the peak of the Euro crisis, a growing body of empirical research on attitudes towards willingness to show fiscal solidarity to countries in need emerged. However, most studies focused on the question to what extent citizens are willing to give financial help to debt-ridden EU Member States (Daniele and Geys 2015; Díez Medrano et al. 2019, p. 145; European Parliament 2012, p. 57; Gerhards et al. 2019, p. 62ff.; Kleider and Stoeckel 2019; Lengfeld et al. 2015, p. 15f., 2020). Although studies consistently point to outstanding country-differences, analyses do not reveal a clear pattern yet: While some found approval rates to be comparably lower in Western, moderate in Eastern, and high in Mediterranean, crisis-affected EU countries (Daniele and Geys 2015, p. 663; Díez Medrano et al. 2019, p. 146; Pew Research Center 2012, p. 32, 2013, p. 25), others detect the lowest support among eastern EU Member States (European Parliament 2012, p. 57; Gerhards et al. 2019, p. 64.; Lengfeld et al. 2015, p. 15f.). Scholars furthermore identified determinants of support for fiscal solidarity with Member States in need. In general, support is higher among those with a higher socio-economic status (Daniele and Geys 2015, p. 659; Kuhn et al. 2018, p. 1772; Stoeckel and Kuhn 2018, p. 457), with leftist political views (Daniele and Geys 2015, p. 664; Díez Medrano et al. 2019, p. 152; Kuhn et al. 2018, p. 1772), cosmopolitan attitudes (Bauhr and Charron 2018, p. 245; Bechtel et al. 2014, p. 846; Díez Medrano et al. 2019, p. 152; Kleider and Stoeckel 2019, p. 14ff.; Lengfeld et al. 2020, p. 351), and a European identity (Díez Medrano et al. 2019, p. 151f.; Kleider and Stoeckel 2019, p. 14ff.; Verhaegen 2018).

Measures of financial assistance for countries in need are always linked to a set of peculiarities. Despite their general shape (e.g. direct transfers monetary payments, loans, or more specified measures such as Eurobonds) this concerns the extent, possible run-time, and of course the conditions under which they are granted. By using (quasi) experimental designs, scholars demonstrated that the level of support depends on the particular conditions under which it is provided. For one, the support of such measures decreases if the absolute extent or the relative share of one’s country as a donor increases (Bechtel et al. 2014, p. 852f., 2017, p. 875). Furthermore, approval rates vary among different potential receiving countries, with comparably lower support for Greece (Bechtel et al. 2017, p. 876; Lengfeld et al. 2012, p. 9f.).

Although part of all financial assistance programmes and highly politicized in the debate, we know little about citizens’ attitudes on specific austerity measures. As research showed, measures are contested between (potential) receiving and creditor countries, with a generally higher demand for measures in the latter (Lengfeld et al. 2012, p. 20f., 2015, p. 20f.). Quantitative case studies showed that while citizens from Germany predominantly demand cuts in the public sector (Lengfeld and Kroh 2016, p. 877; Lengfeld et al. 2012, p. 20, 2015, p. 20), respondents from Portugal and Germany reject cutbacks for the vulnerable, such as social spending or pension cuts (Lengfeld et al. 2012, p. 20, 2015, p. 20). However, these results are contested by a study by Michael M. Bechtel and colleagues among German respondents (Bechtel et al. 2017). In this study, job cuts in the private sector negatively correlate with support for bailout policies, while higher spending cuts positively affect support (Bechtel et al. 2017, p. 875f.).Footnote 2

Studies furthermore reveal that particularly people with leftist political views, or voters of respective leftist parties, more often reject the appliance of austerity measures in their country (Mari et al. 2017, p. 59f.; Rüdig and Karyotis 2013, p. 501) or oppose stricter cutbacks (Bechtel et al. 2017, p. 878f.). Furthermore, socially relative deprived citizens more often deny austerity programmes (Rüdig and Karyotis 2013, p. 501).

However, empirical research on approval of concrete measures of austerity is rare and faced with several restrictions. Studies are mostly restricted to a low number of countries (Díez Medrano et al. 2019; Mari et al. 2017; Pew Research Center 2012, 2013) or are based on case studies only (Bechtel et al. 2014, 2017; Lengfeld and Kroh 2016; Lengfeld et al. 2012; Rüdig and Karyotis 2013). Comprehensive international comparisons are therefore limited or even impossible. Furthermore, the countries analysed often play a concise role in the debt crisis, such as Greece or Germany, and hence do not represent citizens of the EU as a whole. Obviously, the gap in research leaves many questions unanswered.

Divided over austerities?

From our point of view, attitudes towards austerity measures depend on three different groups of reasons: citizen’s socio-economic status, the economic situation of its country of origin, and its ideological worldviews. Starting with the individual socio-economic status, research has shown that socially vulnerable groups expect and hope for their national government to act to improve the life opportunities of the indigenous population. Furthermore, they generally stand to gain from solidarity measures themselves (De Beer 2012; Edlund 2007; Ingensiep 2016). However, these expectations are in contrast to the unequal effects of what austerities produce in the crisis countries. Theoretically, cuts to social state provisions and the raising of value added tax (VAT) threaten the most vulnerable social groups to a higher extent than the middle and upper classes. We therefore expect that citizens holding a lower socio-economic status are more likely to oppose EU austerity measures than citizens with a higher status. This hypothesis is in line with research on the effect of status on support of financial aid for crisis-affected countries (Bauhr and Charron 2018; Kleider and Stoeckel 2019; Kuhn et al. 2018; Verhaegen 2018).

Furthermore, we expect interactions between the individual status and the country’s situation. As the debt crisis has been followed by harsh cutbacks on social provisions, socially deprived people from poorer, crisis-affected countries have experienced the harsh consequences of the sovereign debt crisis by themselves. Kleider and Stoeckel (2019) point out that this experience may amplify the negative association between social status and support for EU transfers. The reverse can be expected to apply to economically well-off people living in wealthier—ergo (potential) creditor—countries who are expected to be the most supportive for European solidarity. We therefore expect that the countries’ condition during the crisis fosters the effect of the individual status on attitudes towards EU austerity measures.

H1a

Low-status citizens are more likely to oppose austerity measures than high-status citizens.

H1b

Low-status citizens living in crisis countries are more likely to oppose austerity measures than low-status citizens living in countries not heavily affected by the crisis.

With regard to the country level, we expect that citizens from (potential) creditor countries support austerity measures as a condition for solidaric actions in principle, and adopt a stance directly opposed to citizens from debtor countries. One of their major motives could be the belief that it is each state’s own responsibility for self-assistance. By this logic, debtor countries should mobilize all forces at their disposal in order to tackle the sovereign debt crisis. Thus, citizens of assisting countries may explicitly want the EU to negotiate far-reaching measures to ensure that the crisis country does everything in its power to overcome sovereign debt. This could be done by executing structural economic, fiscal, and social welfare reforms to strengthen the countries’ prospective economic performance, and/or by taking responsibility for keeping costs down (i.e. Hardiman and Regan 2013; Rogers and Vasilopoulou 2012). Citizens from crisis countries, however, may tend to reject fiscal restrictions, which are considered a threat to individuals’ purses as well as to national wealth, as recently seen in Greece and Portugal (Gerodimos 2013; Kriesi 2012, p. 521). As they have been directly affected by the crisis, e.g. in terms of a growing unemployment rate, they will tend to evaluate the negative short-term effects of austerities on the individual or public budgets to a higher extent than potential long-term effects on economic growth.

H2a

Citizens from countries who had to accept measures imposed by the ‘Troika’ will be more likely to disagree on austerity measures than citizens from countries not affected by EU austerity measures.

H2b

The more heavily affected by the crisis a country was (i.e. growth of unemployment), the more likely it is that its citizens will disagree on austerity measures.

Moreover, a bulk of studies have shown that citizens’ political beliefs represent an interpretive framework through which they assess concrete political events related to the EU and its institutions, such as the bailout issue (Bauhr and Charron 2018; Ciornei and Recci 2017; Díez Medrano et al. 2019; Kleider and Stoeckel 2019; Hutter et al. 2016; Kuhn et al. 2018; Lengfeld et al. 2020; Stoeckel and Kuhn 2018; Verhaegen 2018). In case of austerity measures, we therefore expect right-wing oriented people to regard crisis aid as a threat to national sovereignty, and thus rather reject these measures, compared to citizens of the political centre. However, we expect the same for left-wing citizens who may consider austerities to worsen the position of the most vulnerable and foster social inequality in crisis countries.

H3

Citizens with radical left or right political self-perceptions rather reject EU austerity measures than those in the political centre.

Finally, we expect people who are emotionally bound to Europe and identify themselves as Europeans to be more in favour of applying EU austerity measures. They perceive Europe as a real community in which every member must fulfil duties in order to receive the communities support. In contrast, people who feel strongly connected to their own nation state rather reject Europe as a space of identity and are more likely to be against European fiscal solidarity in general (Kleider and Stoeckel 2019; Kuhn and Stoeckel 2014; Verhaegen 2018). Hence, we expect nationalists also to oppose restrictions to national sovereignty set by transnational institutions like the ‘Troika’.

H4a

People with a European identity are more likely to support EU austerity measures compared to those not identifying with Europe.

H4b

People with a national identity are less likely to support EU austerity measures, compared to those not identifying with their nation.

In line with the concept outlined before, we expect harsh differences of approval of austerity measures especially between different groups of citizens from different countries. We also expect this to be a breeding ground for rejecting solidaric actions and the financial assistance measures themselves. Hence, only low disparities between citizens’ attitudes can help to make austerities part of an accepted package of conditions for these measures.

Data and methods

Data

We rely on data from the ‘Transnational European Solidarity Survey’ (TESS), carried out in 2016. The TESS is a joint-project between two research groups: (1) ‘Solidarity in European Societies: Empowerment, Social Justice and Citizenship (SOLIDUS)’ funded by the European Commission in the context of the Horizon 2020 research programme (Grant Agreement n. 649489), and (2) the German DFG Research Unit ‘Horizontal Europeanization’ funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (FOR 1539). The survey contains questions in different fields of European transnational solidarity: welfare state solidarity, territorial solidarity, refugee solidarity, and fiscal solidarity (Gerhards et al. 2019). For financial reasons, the TESS was restricted to the 13 EU Member States Austria, Cyprus, Germany, Greece, France, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden. The selected countries represent a range of different characteristics, among others whether or not they received financial assistance during the Euro crisis.

After translating the English master questionnaire into the different languages, with an additional check by a translating office, the fieldwork was carried out by Kantar TNS. Respondents eligible to vote and age 18 or above were chosen from national standard list-assisted random digit dialling (RDD) and interviewed using computer-assisted telephone interviewing techniques (CATI). The survey was carried out between June and November 2016.Footnote 3 In 12 countries, 1000 interviews were completed, while the number of interviews for Cyprus was reduced to 500. After dropping cases with missing values in one of the dependent variables (listwise-deletion), our net sample for the general approval rates adds up to 11,623 and 8620 for the multivariate analysis (cases with missing values at the covariates were dropped).

Variables

Preferences towards conditional solidarity are measures by the following question and items:

There are certain measures countries in crisis have to take in order to get financial support from the European Union. Please tell me for each measure to what extent you agree or disagree that countries in crisis should take them in order to get financial support from the EU.

Increase value added tax,

Cut social spending,

Raise the retirement age,

Reduce the number of employees in the public sector.Footnote 4

(Random order; scaling: ‘totally agree’, ‘tend to agree’, ‘tend to disagree’, ‘totally disagree’).

As the items were subject of one or more financial support agreements, the analyses may be regarded as an ex post assessment, taking the qualification into account that it is rather unlikely that citizens from EU Member States are aware of the demand of explicit austerity measures, especially within countries not receiving financial assistance. In our analysis, we analyse each item separately. Additionally, we also constructed an unweighted conditionality index on taking into account the 4-point scale for each item, resulting in a linear index ranging from 0 (not accepting any measures at all) to 12 (highest approval for each measure).

We analyse three groups of independent variables: socio-structural and cultural individual attributes, and country-related macro factors. For the socio-structural factors, we use four variables. Education was measured as an ordinal variable based on national educational degrees (non- or primary, secondary, and tertiary education). We measured the occupational class position according to the EGP scheme (Erikson et al. 1979) by a three-class variable (lower, middle, and higher class). Income was calculated as the net equivalent household income in Euro/PPP as a natural logarithm. For the descriptive analysis, we grouped the respondents equivalent household income in three categories (less than 70%, 70–150%, and higher than 150% of national median income). We additionally use a dummy variable for the current employment situation of the respondent (employed vs. all others). In the descriptive analyses, we focus on the different categories in more detail. For the multivariate analyses, we constructed an index for the socio-structural status similar to the approach described by Winkler and Stolzenberg (1999): Using information on education, occupational class, and household income, each item was transferred into a 7-point-scaleFootnote 5, and an additive index was calculated and standardized ranging from 1 (lowest socio-structural status) to 7 (highest). Albeit the transformation into a linear variable is somewhat problematic due to the categorization of the different groups and the unweighted character of the calculation, it is nevertheless a simple and helpful tool to check our expectations.

To measure cultural factors, we analyse political orientation and identities. The self-placement on the left–right scale (1 = far left, 11 = far right) has been recoded into a 5-point-categorical variable so that people on the poles (values 1 and 2 for the left as well as 10 and 11 for the right) can be compared to people with moderate attitudes (3–5 for the left and 7–9 for the right) and those in the centre (6). Identity is surveyed as three dummy variables for three levels: with one’s nation, Europe, and the world.

On the macro level, we use dummy variables identifying each citizen’s country of residence. As our Hypothesis 2a states a difference for those who received financial assistance during the Euro crisis, we sorted the countries accordingly and furthermore compiled a dummy variable to identify the recipients of financial aid (crisis-affected vs. other Member States). To operationalize the effect of the crisis on each country, we refer to the progression of the unemployment rate between 2008 and 2015 (Eurostat 2018c), actual unemployment rate (Eurostat 2018c), government debt (Eurostat 2018b), and poverty rate (Eurostat 2018a).

We use sex, age (in years and squared), number of kids in household, as well as the migration background of the respondents as control variables (see Table A.1 in the Online Appendix for general descriptive statistics).

Methods

While regression analysis has several advantages when it comes to statistically testing differences between covariates under consideration of control variables, for the question of differences in attitudes, the absolute level of approval for each group is also of importance and not only whether (or not) it differentiates from others. We therefore analyse and discuss descriptive tables for the level of approval for all groups. Here, data have been weighted by age, gender, occupation, employment status, and region (NUTS 2) to account for sample selectivity.Footnote 6 Afterwards, we analyse logistic models with agreement on the measures as the dependent variable (1 = approval, 0 = disapproval) and depict Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) for covariates that are of importance for our hypotheses.

Having only 13 countries in the sample, the sample is too small for multilevel modelling (Bryan and Jenkins 2016). We thus analyse macro factors in accordance with the two-step regression approach (Bryan and Jenkins 2016). To detect systematic differences, in a first step we use separate logistic regressions for each country and austerity measure, to derive Predicted Probabilities (Online Table A.3). In a second step, we analyse their correlation with country-factors. This method is helpful for small case studies such as ours, as it controls for individual-level covariates and yet gives the possibility of analysing and discussing country-level differences in relation to macro factors. Additionally, we use multilevel models as a test for robustness.Footnote 7 For further checks of robustness, we calculated models including the socio-structural status variables education, class, and income instead of the socio-structural index (Table A.4 in the Online Appendix). We also analyse the general approval of austerity measures with the index described above in OLS regression models (Online Table A.5).

Results

Conditionality and transnational conflict lines

Figure 1 depicts descriptive findings on attitudes towards conditionality showing that three of the four items are rejected by about two-thirds of the respondents. Only the reduction of employees in the public sector finds thin majoritarian acceptance (55%).

To depict group differences, we cross-tabulate variables displaying mean levels of approval in Fig. 2.Footnote 8 In line with Hypothesis 1a, citizens with a higher social status (education, class, income) are more in favour of conditional solidarity than lower status citizens. The most notable differences concern the raising of the retirement age. However, differences do not hold true for all covariates and for all conditions. Especially for the question of cutting social spending, the effect is not observable among all factors. Overall, differences seem to be rather small, with the highest difference concerning education in the case of raising the retirement age (29%-points difference between the lowest and the highest educated). The level of approval of the groups only split them into one majority for and one against the measure in two cases.

We find a somewhat closer impact of cultural variables. In general, citizens on the left side of the scale more often disagree on conditionality, whereas higher levels of approval among the political right are depicted. The left–right effect is by tendency linear for the questions on cutting social spending and reducing public employees, while it is u-shaped with lower levels of approval also among the far right for the other items. However, among all measures the moderate right shows the highest level of approval. When we take the absolute level of approval into account, only in case of the acceptance of reducing public employees do we find a majority against this measure (the strong left) while the other groups form a majority in favour.

With regard to respondent’s identities we observe a clear pattern of higher approval rates among those holding a national as well as for those with a European identity. While the latter observation supports Hypothesis 4a, the former is in contrast to Hypothesis 4b. People with a national identity seem to be even more demanding than those who do not identify with their country of origin. Once again, the differences are rather small and do not split the groups into a strong majority of supporters and a majority of non-supporters.

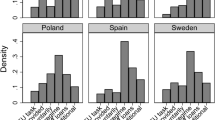

Obviously, the sharpest differences exist between countries. While 71% of Swedes accept the increase of the value added tax, only 20% of the Greek do so. Although this is the biggest gap, for the other conditions of solidarity we can find similar strong differences. Furthermore, for some conditions we identify countries with clear majorities in favour, while the majority of the population of other countries reject them. Respondents from crisis-affected countries tend to disagree on the conditions more often than the overall population. However, this observation has several limitations. First, among the receiving countries Ireland stands out as the most demanding one, meeting the mean level of approval for most of the conditions. Second, regarding the countries not receiving assistance, we find huge variances, with approval rates in some countries being far above the mean and in others far below. Especially in France and Hungary, the levels of approval are comparatively weak. Finally, the pattern does not apply to the reduction of public employees. In this case, we find clear majorities demanding this measure among most of the crisis-affected countries (with the exception of Spain). Taken together, Hypothesis 2a only partially fits as there seems to be a tendency of citizens from crisis-affected countries to be less demanding regarding conditionality that does not apply to all countries and conditions throughout.

Figure 3 presents results of the logistic regressions for selected covariates.Footnote 9 Basically, results support our findings from the descriptive analyses. We find significant positive effects of the social status index for three of the four conditions. Replacing the index by separate variables for education, class, and income (Table A.4 in the Online Appendix) shows that the former two are obviously more decisive for the preferences of the respondents, while the effects for income can be neglected. Anyway, by using a conditionality index as dependent variable (Online Table A.5) the general finding of a positive correlation—that citizens with higher social status rather approve conditional solidarity—confirms our Hypothesis 1a. Albeit this obvious tendency, the AMEs are rather small.

Source TESS (2016), own calculations, own depiction, n = 8620, LOGISTIC Regression with country clustered robust standard errors, Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) including 95%-confidence intervals. Models without (dark bullets) and including interaction effects (grey squares). Extraction from Table A.2

Conflict lines on the agreement of solidarity conditions (Regression).

As stated in Hypothesis 1b, we expected that low-status citizens living in countries heavily affected by the sovereign debt crisis reject the idea of conditionality to a higher extent than low status citizens from other Member States do. In the second model of each regression, we add an interaction effect for the socio-structural index and a dummy identifying the crisis-affected countries. Albeit pointing in the expected negative direction, the effects barely exceed the threshold of significance. Depicting the Predicted Probabilities for each measure (Fig. A.1 in the Online Appendix) makes the interpretation more intuitive: Except for the measure of cutting social expenditures, where the status effect is even negative in crisis-affected countries, effects are positive in both country groups throughout.Footnote 10 Even though the effects appear to be somewhat stronger in countries not affected by the crisis, differences seem to be rather weak. More importantly, those with the lowest socio-structural status barely differ in their approval rates in any of the models. Thus, findings do not confirm Hypothesis 1b.

The analysis of cultural factors supports our previous findings. Figure 3 shows that citizens assigning themselves as far left show remarkably lower approval rates than those from the political centre. The effect is significant for three of the four items. Furthermore, the moderate right is the most demanding group in most models. Taken together, with the lower level of support among the far left and the higher level of approval among the moderate right, political self-placement and attitude towards conditional solidarity seem to be related. Yet, with the far right barely differing from the centre, our expectation of an u-shaped relation (Hypothesis 3) is only supported for the first condition. Regarding collective identity, both national and European identities show a significant effect in two of the four items. Although limited, Hypothesis 4a seems to be accurate. In contrast, Hypothesis 4b must be rejected, as the effect is—contrary to our expectation—clearly positive. With few exceptions, models using an overall measure of approval confirm our results (Table A.5 in the Online Appendix).

Explaining country-differences

The differences of approval between crisis-affected and other countries in Fig. 3 are not or barely significant. Significant differences furthermore vanish in the models including an interaction with the socio-structural index. In contrast to Hypothesis 2a, the question of whether a country has received financial assistance in the past or not, adds little to the explanation of approving conditionality.Footnote 11 Anyway, as Fig. 2 shows, country-differences are remarkable. Multivariate analyses using country-dummies support this finding.Footnote 12 Can macro indicators help us to understand these differences? Fig. 4 depicts the Predicted Probabilities for the mean level of approval for each country (vertical axis; derived from the regression in Online Table A.3). Each diagram represents one solidarity condition. On the horizontal axis, the progression of unemployment rates is depicted (see Online Table A.7 for a correlation matrix).

Source TESS (2016), Eurostat (2018c), own calculations, own depiction, n = 13, Predicted Probabilities from LOGISTIC regression (Online Table A.3)

Agreement on solidarity conditions and progression of unemployment.

Unsurprisingly, crisis-affected countries (dark bullets) experienced a strong negative progression of unemployment, with the greatest increase in Greece by 17%-points. In contrast, the other Member States depicted (grey squares) show comparatively moderate progressions. As the trend lines indicate, countries with a higher increase of unemployment rates during the crisis generally show lower levels of approval. The Irish case is outstanding: Albeit a recipient of financial assistance measures themselves, in Ireland the progression of unemployment and the levels of agreement on conditions are comparable to observations from countries not affected by the crisis. This outlier may explain why Hypothesis 2a has to be rejected. With regard to other macro factors, we find similar results to the trends of unemployment development: Approval rates negatively correlate with a higher level of unemployment, government debt, and poverty (Online Table A.7).

Although these findings confirm Hypothesis 2b, there are some limitations. First, the expected negative correlation does not hold true for the reduction of public employees. Second, there is remarkable variance between respondents from countries not strongly affected by the crisis indicating that the observed negative correlation primarily goes back to the crisis-affected countries. This may also explain why, thirdly, the effects are barely significant (Online Table A.7). In sum, only three of the 16 correlations tested are statistically significant, with only two exceeding the 5% threshold. Taken together, as the general trends in most of the models are negative, our expectation that countries more affected by the crisis are rather critical regarding conditionality applies with limitations.

Conclusion

With the provision of financial assistance to economically distressed countries during the Euro crisis since 2008, there have been serious public controversies on the measures a country has to take in order to receive financial support. These controversies have posed the question to which extent EU citizen’s willingness to show transnational solidarity depends on specific conditions the troubled country has to meet in order to receive financial assistance. As financial assistance has been negotiated and provided by institutions—the EU and the IMF—we therefore hypothesized that attitudes towards conditions of solidarity are, at least to some extent, decisive for the legitimacy of transnational fiscal solidarity at large.

As research on citizens’ acceptance of austerity measures is scarce, in this article we analysed data from the ‘Transnational European Solidarity Survey’ on attitudes towards specific conditions of fiscal solidarity for citizens from 13 EU Member States. Based on theoretical considerations regarding EU citizen’s attitudes towards preconditions of solidaric actions, we derived hypotheses on the individual and country level in order to detect potential socio-structural and cultural conflict lines. Findings showed that a majority of respondents disagreed on the idea of conditionality, as they rejected three of the four proposed conditions, and one (reduction of public employees) found a scarce majority. Further analyses revealed that although respondents with a higher social status and those holding rightist political attitudes are more likely to support conditionality than the most vulnerable strata and the leftist. Furthermore, effects of socio-structural factors are barely stronger in countries that received financial assistance. Not surprisingly, the most remarkable differences occurred among countries. While respondents from crisis-affected countries barely reject the idea of conditionality more often than those from other Member States, in tendency, negative macroeconomic developments lead to lower levels of approval of such measures. However, these effects do not apply to all countries and all austerity measures investigated.

In sum, our findings indicate that the ‘Troika’s’ policy of applying austerity measures to crisis countries seems to be less controversial between the EU citizens than expected. Strikingly, even those living in affluent countries oppose the idea of conditionality, especially those weakening the social welfare of low status persons. Thus, if the EU aims to strengthen the social dimension of Europe, which is widely legitimated by Europeans, it should avoid interventions to the crisis country’s national welfare system. Findings also confirm a general notion of solidarity Europe’s citizens have in mind saying that the economically strongest shall strengthen the most vulnerable in society.

However, if it comes to a new financial crisis in Europe, conditionality may pose a minefield for the EU, leading to a decrease of EU’s legitimacy in the public eye, and may become an implosive political issue likely to be exploited by nationalist actors and populist parties. Hence, European political actors should be careful in choosing appropriate measures for each state. Here, survey research may help to separate between those measures citizens are willing to accept and those perceived as an overburden. As austerity measures always go along with disadvantages for social groups or even whole countries, a solution satisfying all actors involved seems to be impossible. Sensitivity may be the key to find satisfactory and effective measures to help countries out of their misery.

Finally, our study faces two major limitations. First, with 13 countries in the sample we do not cover the entire EU. The validation and explanation of the country-differences identified may be target of future studies that use further-reaching data. Second, as our data are from 2016, the analyses only provide us with a ‘snapshot’ of attitudes from the aftermath of the heydays of the Euro crisis. An ongoing surveying of citizens attitudes on austerity measures could help to answer questions of stability over time and in case of new external shocks.

Notes

These bailout programmes were implemented for Ireland, Cyprus, Greece, and Portugal. Spain received only financial assistance for stabilizing the banking sector and did not have to agree to austerity measures.

One explanation of these differences may be the research design of the study from Michael M. Bechtel and colleagues. The experimental design applied is restricted to direct comparisons only. As all scenarios are compared in reference with the scenario of a minimal spending cut (Bechtel et al. 2017, p. 875), an inference on the absolute level of approval or denial for each scenario is not possible.

The interview period of several months is due to different starting points of field times within the countries. Individually, surveying did not exceed a maximum of 37 days within each country (for further information see Gerhards et al. 2019). We recognize that this poses a limitation in regard of comparability to a certain degree. Therefore, we would like to discuss some events and the context that may have influenced answer behaviour. For one, the British referendum on leaving the EU for good took place on 23 June. As the United Kingdom was not part of the survey, only indirect effects may be expected in the countries in focus here. Second, general elections took place in Spain on 26 June. Although Spain was hit hard by the crises, e.g. with high youth unemployment rates, the country has not received financial assistance measures by the Troika since 2013. Furthermore, descriptive analyses revealed that differences in approval of solidarity conditions changed after the election in Spain barley and not significantly at all. Finally, over the period of fieldwork, Greece was the only country still receiving financial assistance and was subject to austerity measures. As the difference between receiving and non-receiving countries is subject of this paper (see “State of research” section), we will discuss experience with financial assistance measures anyhow. In conclusion, the period of fieldwork does not pose a problem, as the topic was only highly salient and driven by emotions in Greece at that time—a fact we will take into account in the analyses.

A fifth item has been ‘raise wealth tax’. For our analysis, we skipped this item as it did not correspond to any austerity measure introduced by the institutions.

For income, we grouped citizens in septiles, according to their income position within the distribution of the country. For education, the 7-class grouping was used that is part of the data, with those without formal qualification (coded as 1), lower secondary (2), upper secondary vocational (3), upper secondary education (4), post-secondary education below bachelor (5), medium duration higher education (6), and long duration higher education (7). Finally, the occupational classes were coded as provided in the data as well, with the unskilled manual and agricultural workers (coded as 1), routine non-manuals (2), self-employed (3), lower middle classes (4), centre middle classes (5), upper middle class (6), and the upper class (7).

The weights have been calculated by the opinion institute Kantar TNS. In a multi-stage procedure, information on the sampling process (design weights) as well as the population stratification (post stratification weights) were taken into account using information from official resources (e.g. Eurostat). For more information see Gerhards et al. (2019).

In general, the multilevel models confirm our findings with fixed effects for countries (upon request). Yet, the fixed effect models estimate standard errors more conservatively and due to the findings of Bryan and Jenkins (2016), we prefer referring to the more strict modelling.

Compared with Fig. 1, the level of approval for each measure is slightly biased, due to the listwise-deletion of cases with missing values of the covariates (see “Divided over austerities?” section).

The models with all covariates are depicted in Table A.2 in the Online Appendix. Regarding the control variables, women are more likely to reject measures than men. We also find mixed effects for the linear age factor as well as the migration background over the different dependent variables. A higher number of kids in the household furthermore goes along with a higher rate of approval for measures. Nevertheless, only the effects for increasing the valued added tax and raising the retirement age are significant.

Results from separate analyses for both country groups support these findings (Table A.6 in the Online Appendix).

As Online Table A.5 shows, the effect is also only significant at the 5% threshold regarding the general index for approval of conditions.

Significant differences can be identified for each solidarity condition (Table A.3 in the Online Appendix) as well as for the conditionality index (Online Table A.5).

References

Bauhr, M., and N. Charron. 2018. Why support International redistribution? Corruption and public support for aid in the Eurozone. European Union Politics 19 (2): 233–254.

Bechtel, M.M., J. Hainmueller, and Y. Margalit. 2014. Preferences for international redistribution: The divide over the eurozone bailouts. American Political Science Review 58 (4): 835–856.

Bechtel, M.M., J. Hainmueller, and Y. Margalit. 2017. Policy design and domestic support for international bailouts. European Journal of Political Research 56: 864–886.

Bryan, M.L., and S.P. Jenkins. 2016. Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review 32 (1): 3–22.

Bugge, A. and A. Khalip. 2013. Portuguese stage general strike against relentless austerity. Reuters, 27 June. https://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/27/us-portugal-strike-transport-idUSBRE95Q09N20130627. Accessed 11 Nov 2017.

Buß, C., B. Ebbinghaus, and E. Naumann. 2017. Making Deservingness of the unemployed conditional: Changes in public support for the conditionality of unemployment benefits. In The social legitimacy of targeted welfare: Attitudes to welfare deservingness, ed. W.V. Oorschot, F. Roosma, B. Meuleman, and T. Reeskens, 167–185. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Callan, T., C. Leventi, H., Levy, M., Matsaganis, A., Paulus, and H. Sutherland. 2011. Social Situation Observatory—Income distribution and living conditions. Research Note 2/2011: The distributional effects of austerity measures: A comparison of six EU countries. European Commission. https://www.esri.ie/system/files/media/file-uploads/2015-07/BKMNEXT209.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2019.

Carriero, R., and M. Filandri. 2019. Support for conditional unemployment benefit in European countries: The role of income inequality. Journal of European Social Policy 29 (4): 498–514.

Ciornei, I., and E. Recchi. 2017. At the source of European solidarity: Assessing the effects of cross-border practices and political attitudes. Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (3): 468–485.

Daniele, G., and B. Geys. 2015. Public support for European fiscal integration in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy 22 (5): 650–670.

De Beer, P. 2012. Earnings and income inequality in the EU during the crisis. International Labour Review 151 (4): 313–331.

Díez Medrano, J., I. Ciornei, and F. Apaydin. 2019. Explaining solidarity in the European union. In Everyday Europe: Social transnationalism in an unsettled continent, ed. E. Recchi, A. Favell, F. Apaydin, R. Barbulescu, M. Braun, I. Ciornei, N. Cunningham, J. Díez Medrano, D.N. Duru, L. Hanquinet, J.S. Jensen, S. Pötzschke, D. Reimer, J. Salamonska, M. Savage, and A. Varela, 137–170. Bristol: Policy Press.

Dyson, K. 2017. Playing for high stakes. The eurozone crisis. In The European union in crisis, ed. D. Dinan, N. Nugent, and W.E. Paterson, 54–76. London: Palgrave.

Edlund, J. 2007. Class conflicts and institutional feedback effects in liberal and social democratic welfare regimes. In The political sociology of the welfare state, ed. S. Svallfors, 30–79. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Erikson, R., J.H. Goldthorpe, and L. Portocarero. 1979. Intergenerational class mobility in three western European societies: England, France and Sweden. The British Journal of Sociology 30 (4): 415–441.

European Parliament. 2012. Special eurobarometer/wave 76.1—TNS opinion & social. Crisis. Report, www.europarl.europa.eu/pdf/eurobarometre/2011/decembre/rapport_en.pdf. Accessed 23 Feb 2016.

Eurostat. 2018a. At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold, age and sex—EU-SILC survey. Eurostat data explorer, 23 October. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_li02&lang=en. Accessed 26 Oct 2018.

Eurostat. 2018b. General government gross debt—annual data. Eurostat data explorer, 18 August, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=teina225. Accessed 26 Oct 2018.

Eurostat. 2018c. Unemployment by sex and age—annual average. Eurostat data explorer, 01 October, https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=une_rt_a&lang=en. Accessed 08 Oct 2018.

Gelissen, J. 2000. Popular support for institutionalised solidarity: A comparison between European welfare states. International Journal of Social Welfare 9 (4): 285–300.

Gerhards, J., H. Lengfeld, Z.S. Ignácz, F.K. Kley, and M. Priem. 2019. European solidarity in times of crisis: Insights from a Thirteen-Country Survey. London: Routledge.

Gerodimos, R. 2013. Greece: Politics at the crossroads. Political Insight 4 (1): 16–19.

Hardiman, N., and A. Regan. 2013. The Politics Of Austerity in Ireland. Intereconomics 48 (1): 9–14.

Hutter, S., E.M. Grande, and H. Kriesi. 2016. Politicising Europe: Integration and mass politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ingensiep, C. 2016. Determinants of persistent poverty. Do institutional factors matter? In Exploring inequality in Europe: Diverging income and employment opportunities in the crisis, ed. M. Heidenreich, 48–67. Cheltenham: Palgrave.

Kleider, H., and F. Stoeckel. 2019. The politics of international redistribution: Explaining public support for fiscal transfers in the EU. European Journal of Political Research 58 (1): 4–29.

Koos, S. 2019. Crises and the reconfiguration of solidarities in Europe—origins, scope, variations. European Societies 21 (5): 629–648.

Kriesi, H. 2012. The political consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe: Electoral punishment and popular protest. Swiss Political Science Review 18 (4): 518–522.

Kuhn, T., F. Nicoli, and F. Vandenbroucke. 2020. Preferences for European unemployment insurance: A question of economic ideology or EU support? Journal of European Public Policy 27 (2): 208–226.

Kuhn, T., H. Solaz, and E.J. van Elsas. 2018. Practising what you preach: How cosmopolitanism promotes willingness to redistribute across the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (12): 1759–1778.

Kuhn, T., and F. Stoeckel. 2014. When European integration becomes costly: The Euro crisis and public support for European economic governance. Journal of European Public Policy 21 (4): 624–641.

Kulish, N., and S. Castle. 2011. Slovakia Rejects Euro Bailout. The New York Times, 11 October. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/12/world/europe/slovak-leader-vows-to-resign-if-bailout-vote-fails.html. Accessed 19 July 2017.

Larsen, C.A. 2008. The political logic of labour market reforms and popular images of target groups. Journal of European Social Policy 18 (1): 50–63.

Lengfeld, H. and M. Kroh. 2016. Solidarity with EU countries in crisis: Results of a 2015 socio-economic panel (SOEP) survey. DIW Economic Bulletin 6 (39): 473–479.

Lengfeld, H., F.K. Kley, and J. Häuberer. 2020. Contemplating the Eurozone crisis: Are European citizens willing to pay for a European solidarity tax? Evidence from Germany and Portugal. European Societies 22 (3): 337–367.

Lengfeld, H., S. Schmidt, and J. Häuberer. 2012. Solidarität in der europäischen Fiskalkrise: Sind die EU-Bürger zu finanzieller Unterstützung von hoch verschuldeten EU-Ländern bereit? Erste Ergebnisse aus einer Umfrage in Deutschland und Portugal. Hamburg Reports on Contemporary Societies. Report Nr. 05/2012. Universität Hamburg.

Lengfeld, H., S. Schmidt, and J. Häuberer. 2015. Is there a European solidarity? Attitudes towards fiscal assistance for debt-ridden European Union member states. Working Paper Series of the Department of Sociology at the University of Leipzig, No. 67, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2597605. Accessed 19 July 2017.

Mari, S., C. Volpato, S. Papastamou, X. Chryssochoou, G. Prodromitis, and V. Pavlopoulos. 2017. How political orientation and vulnerability shape representations of the economic crisis in Greece and Italy. International Review of Social Psychology 30 (1): 52–67.

Oorschot, W.V. 2000. Who should get what, and why? On deservingness criteria and the conditionality of solidarity among the public. Policy & Politics 28 (1): 33–48.

Oorschot, W.V., and F. Roosma. 2017. The social legitimacy of targeted welfare and welfare deservingness. In The social legitimacy of targeted welfare: Attitudes to welfare deservingness, ed. W.V. Oorschot, F. Roosma, B. Meuleman, and T. Reeskens, 3–34. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Pew Research Center. 2012. European Unity on the Rocks. Greeks and Germans at Polar Opposites. Global Attitudes Project, 29 May. https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2012/05/Pew-Global-Attitudes-Project-European-Crisis-Report-FINAL-FOR-PRINT-May-29-2012.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Pew Research Center. 2013. The New Sick Man of Europe: the European Union, 13 May. https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2013/05/Pew-Research-Center-Global-Attitudes-Project-European-Union-Report-FINAL-FOR-PRINT-May-13-2013.pdf. Accessed 8 Aug 2018.

Rogers, C., and S. Vasilopoulou. 2012. Making sense of greek austerity. The Political Quarterly 83 (5): 777–785.

Rüdig, W., and G. Karyotis. 2013. Who protests in Greece? Mass opposition to austerity. British Journal of Political Science 44 (3): 487–513.

SPIEGEL Online. 2012. SPIEGEL Interview with Finland's Finance Minister ‘Our Solidarity Is Limited’. 24 July, https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/finnish-finance-minister-defends-debt-agreements-with-spain-and-greece-a-846096.html. Accessed 19 July 2017.

Stoeckel, F., and T. Kuhn. 2018. Mobilizing citizens for costly policies: The conditional effect of party cues on support for international bailouts in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (2): 446–461.

Vandenbroucke, F., B. Burgoon, T. Kuhn, F. Nicoli, S. Sacchi, D. van der Duin and S. Hegewald. 2018. Risk sharing when unemployment hits: How policy design influences citizen support for European Unemployment Risk Sharing (EURS). AISSR Policy Report 1 (December 2018).

Varoufakis, Y. 2017. Adults in the room. My battle with Europe’s deep establishment. London: Penguin Random House UK.

Verhaegen, S. 2018. What to expect from European identity? Explaining support for solidarity in times of crisis. Comparative European Politics 16 (5): 871–904.

Weber, M. 1968. Economy and society 1. New York: Bedminster Press.

Winkler, J., and J. Stolzenberg. 1999. Der Sozialschichtindex im Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey. Gesundheitswesen 61 (Sonderheft 2): 178–183.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research has been the result of a cooperation of the research project ‘Solidarity in European Societies: Empowerment, Social Justice and Citizenship (SOLIDUS)’ funded by the European Commission in the context of the Horizon 2020 research programme (Grant Agreement n. 649489), and the German DFG Research Unit ‘Horizontal Europeanization’ funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (FOR 1539).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lengfeld, H., Kley, F.K. Conditioned solidarity: EU citizens’ attitudes towards economic and social austerities for crisis countries receiving financial aid. Acta Polit 56, 330–350 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00179-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-020-00179-z