Abstract

From a representation theory point of view, trust in political institutions is strongly related to the responsiveness of these institutions to citizens’ preferences. However, is this also true when the political power of citizens is not equal, which is often the case in more unequal societies? In this article, it is argued that the link between perceptions of responsiveness to individual preferences and political trust differs across equal and unequal societies. We find that in inclusive societies, perceived political responsiveness is strongly related to political trust, whereas this link becomes weaker in more unequal societies. In other words, when economic inequality and exclusion are high, traditional accountability mechanisms between political actors and their citizens are less apparent. We speculate that this weaker link is due to habituation or a lack of political engagement, causing citizens to withdraw from political life altogether. The focus of this article lies on European and OECD-member countries. The study uses data from the International Social Survey Programme and the European Social Survey.

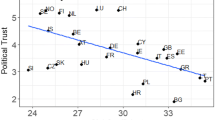

Note: These plots represent the marginal effect of perceived responsiveness on political trust, when controlling for the effect of the Gini coefficient of income or the net poverty rate. The grey areas represent the confidence bounds (95%), and the distribution of country scores is plotted at the bottom of the figure. All models are estimated with the REML approach and controlled for the described individual and country level variables. Unstandardised data are reported for ease of interpretation. The models are robust for outliers (tested with jackknifing)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that surveys were sometimes fielded in 2 years within one country. Macro-level data are based on the last year of fielding.

Countries participating in the ISSP round of 2004 and 2014 on Citizenship but not analysed are the Dominican Republic, Georgia, India, the Philippines, Russia, Taiwan, South Africa and Venezuela.

This question is similar—though not identical—to one of the political trust questions within the American National Elections Study, which asks respondents the following: "How much of the time do you think you can trust the government in Washington to do what is right-just about always, most of the time or only some of the time?".

Note that the questions are also used to gauge external efficacy. Within the ISSP there are no distinct measurements of both concepts. When efficacy and perceived responsiveness are operationalised separately, the indicators correlate strongly (Esaiasson et al. 2015). This is not surprising, because both perceived responsiveness and external efficacy are operationalisations of the broader concept of political accountability (Weatherford 1992). In the European Social Survey 2012 round, different indicators of responsiveness are included. In this article, we will use questions that lie closer to the ideal operationalisation of perceived responsiveness, as put forward by Powell (2004) or Esaiasson et al. (2015): “how often you think the government in [country] today changes its planned policies in response to what most people think?” and “how often you think the government in [country] today sticks to its planned policies regardless of what most people think?” (more information in Appendix 4).

The correlation (Pearson’s correlation) with political trust was 0.12 for whether respondents thought that they had no influence on what government does and 0.31 for the question on government did not care what people like them thought.

For the replication analyses on the basis of the ESS, we use the at-risk-of-poverty and social exclusion rate of Eurostat, which had a broader coverage of the ESS participant countries. Using the OECD country data for poverty delivered substantially equal results.

Similar problems are encountered when gathering data from other sources, such as the World Bank or Eurostat.

In addition, no information is available for Switzerland in 2005.

A small note on the collection of the data. In some cases, I had to impute data to acquire data for all countries. First, there are only data available until 2015. As the ISSP surveys were only fielded in 2016 in Austria and between 2015 and 2016 in Belgium, the latest available information (of 2015) was imputed.

All CPI scores correspond with the year in which survey was fielded, with 2015 data for Australia and Denmark.

Model 1 is based on the same analyses as Model 5 of Table 5.

Note that this is a recurring problem in social sciences research (Bryan and Jenkins 2016). Other studies (cited in this article) on political trust faced similar issues with a limited N at the second level, including Anderson and Singer (2008) (20 countries); Hakhverdian and Mayne (2012) (21 countries) or Zmerli and Castillo (2015) (18 countries).

No questions on voting behaviour during the last general election were asked in the 2004 round.

References

Andersen, R. 2012. Support for Democracy in Cross-National Perspective: The Detrimental Effect of Economic Inequality. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 30 (4): 389–402.

Anderson, C.J., A. Blais, S. Bowler, T. Donovan, and O. Listhaug. 2005. Losers’ Consent. Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, C.J., and M.M. Singer. 2008. The Sensitive Left and the Impervious Right. Multilevel Models and the Politics of Inequality, Ideology, and Legitimacy in Europe. Comparative Political Studies 41 (4/5): 564–599.

Almond, G., and S. Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Armingeon, K., and L. Schädel. 2015. Social Inequality and Political Participation: The Dark Sides of Individualisation. West European Politics 38 (1): 1–27.

Atkinson, A.B. 2015. Inequality. What Can Be Done?. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Barber, B.R. 1984. Strong Democracy. Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bartels, L. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bryan, M.L., and S.P. Jenkins. 2016. Multilevel Modelling of Country Effects: A Cautionary Tale. European Sociological Review 32 (1): 3–22.

Catterberg, G., and A. Moreno. 2006. The Individual Bases of Political Trust. Trends in New and Established Democracies. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18 (1): 31–48.

Craig, S.C. 1979. Efficacy, Trust and Political Behavior. An Attempt to Resolve a Lingering Conceptual Dilemma. American Politics Quarterly 7 (2): 225–239.

Dahlberg, S., J. Linde, and S. Holmberg. 2015. Democratic Discontent in Old and New Democracies. Assessing the Importance of Democratic Input and Governmental Output. Political Studies 63 (1): 18–37.

Dalton, R.J., and C. Welzel (eds.). 2014. The Civic Culture Transformed. From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dunn, K. 2015. Voice, Representation and Trust in Parliament. Acta Politica 50 (2): 171–192.

Easton, D. 1965. A Framework for Political Analysis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Easton, D. 1975. A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support. British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457.

Elff, M., Heisig, J.P., Schaeffer, M. and Shikano, S. 2016. No Need to Turn Bayesian in Multilevel Analysis with Few Clusters: How Frequentist Methods Provide Unbiased Estimates and Accurate Inference. https://osf.io/fkn3u/. Accessed 20 February 2017.

Enders, C.K., and D. Tofighi. 2007. Centering Predictor Variables in Cross-Sectional Multilevel Models: A New Look at an Old Issue. Psychological Methods 12 (2): 121–138.

Esaiasson, P., A.K. Kölln, and S. Turper. 2015. External Efficacy and Perceived Responsiveness: Similar but Distinct Concepts. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 27 (3): 432–445.

Eurostat. 2017. European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-statistics-on-income-and-living-conditions. Accessed 6 June 2017.

Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilens, M. 2005. Inequality and Democratic Responsiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly 69 (5): 778–796.

Goodin, R., and J. Dryzek. 1980. Rational Participation: The Politics of Relative Power. British Journal of Political Science 10 (3): 273–292.

Gould, E.D., and Hijzen, A. 2016. Growing Apart, Losing Trust? The Impact of Inequality on Social Capital. IMF Working Paper No. 176. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Hakhverdian, A., and Q. Mayne. 2012. Institutional Trust, Education and Corruption: A Micro-Macro Interactive Approach. Journal of Politics 74 (3): 739–750.

Hox, J.J. 2010. Multilevel Analysis. Techniques and Applications. New York: Routledge.

ISSP Research Group. 2017. International Social Survey Programme: Citizenship. https://www.gesis.org/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/citizenship/. Accessed 7 June 2017.

Jensen, C., and K. van Kersbergen. 2017. The Politics of Inequality. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jost, J.T., B.W. Pelham, O. Sheldon, and B.N. Sullivan. 2003. Social Inequality and the Reduction of Ideological Dissonance on Behalf of the System: Evidence of Enhanced System Justification Among the Disadvantaged. European Journal of Social Psychology 33 (1): 13–36.

Kölln, A.K. 2016. The Virtuous Circle of Representation. Electoral Studies 42: 126–134.

Krieckhaus, J., B. Son, N.M. Bellinger, and J.M. Wells. 2014. Economic Inequality and Democratic Support. Journal of Politics 76 (1): 139–151.

Kumlin, S. 2004. The Personal and the Political: How Personal Welfare State Experiences Affect Political Trust and Ideology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kumlin, S. 2011. Dissatisfied Democrats, Policy Feedback and European Welfare States, 1976–2001. In Political Trust. Why Context Matters, ed. S. Zmerli and M. Hooghe, 163–186. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Levi, M., and L. Stoker. 2000. Political Trust and Trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science 3: 475–507.

Loveless, M. 2013. The Deterioration of Democratic Political Culture: Consequences of the Perception of Inequality. Social Justice Research 26 (4): 471–491.

Luskin, R. 1990. Explaining Political Sophistication. Political Behavior 12 (4): 331–361.

Mansbridge, J. 2003. Rethinking Representation. American Political Science Review 97 (4): 515–528.

Marshall, T.H. 1964. Class, Citizenship, and Social Development. Garden City: Doubleday.

Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. What are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies. Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62.

Niemi, R.G., S.C. Craig, and F. Mattei. 1991. Measuring Internal Efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study. American Political Science Review 85 (4): 1407–1413.

Norris, P. 2011. Democratic Deficit. Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, M. 2015. The Economic Roots of External Efficacy: Assessing the Relationship Between External Political Efficacy and Income Inequality. Canadian Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 791–813.

OECD. 2017a. Income Distribution and Poverty. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=IDD. Accessed 6 June 2017.

OECD. 2017b. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Piketty, T. 2013. Le Capital au XXIe Siècle. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Powell, G.B. 2004. The Quality of Democracy: The Chain of Responsiveness. Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 91–105.

Ravallion, M. 2003. The Debate on Globalization, Poverty and Inequality: Why Measurement Matters. International Affairs 79 (4): 739–753.

Rosset, J., N. Giger, and J. Bernauer. 2013. More Money, Fewer Problems? Cross-Level Effects of Economic Deprivation on Political Representation. West European Politics 36 (4): 817–835.

Rothstein, B. 2011. The Quality of Government: Corruption, Social Trust and Inequality in International Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Salverda, W., B. Nolan, and T.M. Smeeding (eds.). 2009. The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scheve, K., and D. Stasavage. 2017. Wealth Inequality and Democracy. Annual Review of Political Science 20: 451–468.

Solt, F. 2008. Economic Inequality and Democratic Political Engagement. American Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 48–60.

Solt, F. 2010. Does Economic Inequality Depress Electoral Participation? Testing the Schattschneider Hypothesis. Political Behaviour 32 (2): 285–301.

Solt, F. 2015. Economic Inequality and Nonviolent Protest. Social Science Quarterly 96 (5): 1314–1327.

Solt, F. 2016. The Standardized World Income Inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly 97 (5): 1267–1281.

Stiglitz, J.E. 2012. The Price of Inequality. New York: Norton.

Torcal, M., E. Bonet, and M. Costa Lobo. 2012. Institutional Trust and Responsiveness in the EU. In The Europeanization of National Polities? Citizenship and Support in a Post-Enlargement Union, ed. D. Sanders, P. Belluci, G. Tóka, and M. Torcal, 91–111. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Torcal, M. 2014. The Decline of Political Trust in Spain and Portugal: Economic Performance or Political Responsiveness. American Behavioral Scientist 58 (12): 1542–1567.

Transparency International. 2017. Corruption Perceptions Index 2016. 25 January, https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016. Accessed 6 June 2017.

Tyler, T.R. 2001. The Psychology of Public Dissatisfaction with Government. In What is it About Government that Americans Dislike?, ed. J.R. Hibbing and E. Theiss-Morse, 227–242. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uslaner, E. 2008. Corruption, Inequality, and the Rule of Law: the Bulging Pocket Makes the Easy Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van der Meer, T. 2017. Democratic Input, Macroeconomic Output and Political Trust. In Handbook on Political Trust, ed. S. Zmerli and T. van der Meer, 270–284. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Verba, S., K.L. Schlozman, and H.E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality. Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Weatherford, S.M. 1992. Measuring Political Legitimacy. American Political Science Review 86 (1): 149–166.

World Bank. 2017. GDP Per Capita (current US$). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD. Accessed 6 June 2017.

Zmerli, S., and M. Hooghe (eds.). 2011. Political Trust. Why Context Matters. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Zmerli, S., and J.C. Castillo. 2015. Income Inequality, Distributive Fairness and Political Trust in Latin America. Social Science Research 52: 179–192.

Zmerli, S., and T. van der Meer (eds.). 2017. Handbook on Political Trust. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 7.

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

See Table 10.

Appendix 4: Replication of analyses with the 2012 European Social Survey

Note: These plots represent the marginal effect of perceived responsiveness on political trust, when controlling for the effect of the Gini coefficient of income or the at-risk-of poverty and social exclusion rate. The grey areas represent the confidence bounds (95%), the distribution of country scores is plotted at the bottom of the figure. All models are estimated with the REML approach and controlled for the described individual and country level variables. Unstandardised data are reported for ease of interpretation. The models are robust for outliers (tested with jackknifing). Data: European Social Survey. These figures are replications of Fig. 1

Marginal Effects of Perceived Responsiveness on Political Trust.

Appendix 5

See Table 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goubin, S. Economic inequality, perceived responsiveness and political trust. Acta Polit 55, 267–304 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0115-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0115-z