Abstract

The growing platform economy has revived the debate on the applicability of internalization theory in contemporary contexts. In moving this debate forward, we draw on insights from hybrids research and property rights theory to complement the internalization school. Our core contribution lies in a reconceptualization of platforms as a hybrid organizational form enabling the exchange of property rights between platform owners and complementors. Using social platforms as an example, we propose that improvement in a host country’s intellectual property protection will increase the multinational platform’s (MNP) level of internalization, and that the platform firm’s governance capabilities may weaken the effect of institutions on its operation mode. Our theoretical analysis yields new insights beyond the received view of internationalization that builds on the assumption of internalized proprietary resources. We conclude that internalization theory, as an overarching paradigm in IB, remains adaptable to new organizational forms in the digital economy.

Résumé

La croissance de l'économie des plateformes a relancé le débat sur l'applicabilité de la théorie de l'internalisation dans les contextes contemporains. Dans le but de faire avancer ce débat, nous nous appuyons sur la recherche portée sur les formes hybrides et la théorie des droits de propriété afin de compléter la perspective de l’internalisation. Notre principale contribution consiste à reconceptualiser des plateformes comme une forme organisationnelle hybride permettant l'échange de droits de propriété entre les propriétaires de plateformes et les contributeurs. En utilisant comme exemple les plateformes sociales, nous proposons que l'amélioration de la protection de la propriété intellectuelle d'un pays d’accueil augmente le niveau d'internalisation de la plateforme multinationale (Multinational Platform - MNP), et que les capacités de gouvernance de l'entreprise plateforme peuvent affaiblir l'impact des institutions sur son mode de fonctionnement. Notre analyse théorique apporte de nouveaux regards au-delà de la vision partagée sur l'internationalisation laquelle s'appuie sur le postulat d’internalisation des ressources propriétaires. Nous concluons que la théorie de l'internalisation, en tant que paradigme fondamental dans le domaine des affaires internationales, reste adaptable aux nouvelles formes organisationnelles de l'économie numérique.

Resumen

La cada vez mayor economía de plataformas ha reavivado el debate sobre la aplicabilidad de la teoría de la internalización en contextos contemporáneos. Para hacer avanzar este debate, nos basamos en las ideas de la investigación sobre los híbridos y la teoría de los derechos de propiedad para complementar la escuela de la internalización. Nuestra contribución central radica en la reconceptualización de las plataformas como una forma de organización híbrida que permite el intercambio de derechos de propiedad entre los propietarios de las plataformas y quienes los complementan. Utilizando las plataformas sociales como ejemplo, proponemos que la mejora en la protección de la propiedad intelectual de un país anfitrión aumentará el nivel de internalización de la plataforma multinacional (MNP por sus siglas en inglés), y que las capacidades de gobernanza de la empresa de la plataforma pueden debilitar el efecto de las instituciones en su modo de funcionamiento. Nuestro análisis teórico arroja nuevos aportes que van más allá de la visión recibida de la internacionalización, que se basa en el supuesto de la internalización de los recursos de propiedad. Llegamos a la conclusión de que la teoría de la internalización, como paradigma general de negocios internacionales, sigue siendo adaptable a las nuevas formas organizativas de la economía digital.

Resumo

A crescente economia de plataforma reviveu o debate sobre a aplicabilidade da teoria da internalização em contextos contemporâneos. Ao avançar este debate, recorremos a insights da pesquisa de híbridos e da teoria sobre direitos de propriedade para complementar a escola de internalização. Nossa contribuição principal reside em uma reconceituação de plataformas como uma forma organizacional híbrida que permite a troca de direitos de propriedade entre proprietários de plataformas e complementadores. Usando plataformas sociais como exemplo, propomos que a melhoria na proteção de propriedade intelectual de um país anfitrião aumentará o nível de internalização de plataformas multinacionais (MNP) e que as capacidades de governança da empresa de plataforma podem enfraquecer o efeito de instituições em seu modo de operação. Nossa análise teórica gera novos insights além da visão recebida de internacionalização que se baseia na suposição de recursos proprietários internalizados. Concluímos que a teoria da internalização, como paradigma dominante em IB, permanece adaptável a novas formas organizacionais na economia digital.

摘要

日益增长的平台经济重新引发了关于内部化理论在当代情境中的适用性的辩论。在推进这场辩论时, 我们借鉴了混合研究和产权理论的洞见来补充内部化学派。我们的核心贡献在于将平台重新概念化为一种混合组织形式, 使平台所有者和补充者之间能够交换产权。以社交平台为例, 我们提出东道国知识产权保护的改进会提高跨国平台 (MNP) 的内部化水平, 平台公司的治理能力可能会削弱制度对其运营模式的影响。我们的理论分析提出了超越公认的建立在内部化专有资源假设之上的国际化观点的新见解。我们得出结论, 内部化理论作为国际商务(IB) 的一个总体范式, 仍适用于数字经济中的新组织形式。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

International business (IB) research has long maintained that multinational enterprises (MNEs) primarily compete on proprietary intangible assets, among other resources and capabilities (Dunning, 1988). Institutional deficiencies that raise transaction costs, and particularly appropriability hazards in the host country, will lead MNEs to internalize the production and exchange of value-creating resources (Oxley, 1999; Zhao, 2006). Underlying this literature is the assumption that the advantages an intellectual property (IP) accrues to an MNE is attributable to asset ownership (Dunning & Lundan, 2008).

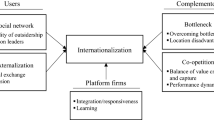

This assumption seems much contested by recent research on digitalization. IB scholars and policymakers have drawn significant attention to a new organizational form, digital platforms, which underpins emerging patterns of internationalization in the modern digital economy (Verbeke & Hutzschenreuter, 2021). Platforms refer to a stable set of common technological resources, standards and capabilities for organizing the production of complementary products, and curating an Internet-based intermediary for the exchange between customers and suppliers of complementary products (Chen, Tong, Tang, & Han, 2022). Unlike conventional MNEs, multinational platforms (MNPs) derive advantages from both their proprietary resources and complementary resources, to which platform firms themselves do not possess legal ownership rights (Li, Chen, Yi, Mao, & Liao, 2019). That poses notable challenges to our understanding of internationalizing firms, which rests upon their internalized resources.

One of the challenges emerged concerns whether platforms, relying much on the externalization of productive activities (Chen, Shaheer, Yi, & Li, 2019), warrant explanations lying beyond transaction cost thinking. Some scholars submit that platforms represent a distinctly new organizational form (Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2019), while others demonstrate that they lie between the polar cases of markets and hierarchies and should fit in the eclectic category of hybrids (Hennart, 2019). To push the debate forward, we seek to provide a unifying account. We show that platforms remain, at the very essence, compatible with modern extensions of internalization theory (Liesch, Buckley, Simonin, & Knight, 2012; Narula, Asmussen, Chi, & Kundu, 2019), although gaining a fuller understanding requires insights from hybrids research and property rights theory.1 What distinguishes MNPs from modern MNEs is that the former ‘quasi-internalize’ complementors’ productive capabilities through the exchanges of property rights, instead of formally instituted market transactions or the purchase of partners’ assets. This conceptual underpinning allows us to explore what determines MNPs’ mode of operation in international markets.

To illustrate this point, the paper uses social platforms as an example. For social platforms such as YouTube and TikTok, a significant amount of value accrues from user-generated content (UGC) (Zhang & Sarvary, 2015), of which users around the world, instead of the firm, create and own the property rights (i.e., copyrights). A fundamental idea of our conceptualization contends that social-platform firms devolve some degree of decision rights, such that users can access the platform interface and contribute original content (Tiwana, Konsynski, & Bush, 2010); in return, platform firms will gain and deploy the rights to distribute and commercialize the UGC, from which their revenues accrue. While other forms of externalization such as outsourcing appear fueled by better enforcement of IPR (Liesch et al., 2012), we argue that deficiencies in IPR protection are in favor of inter-firm collaboration between platform owners and complementors while improvement in IPR regimes will lead to greater internalization in a host market. This departs from the conventional view that MNEs resort to hierarchical governance in weak IP institutions (Oxley, 1997; Rugman, Verbeke, & Nguyen, 2011). We further posit that the platform owner’s governance capability may weaken the impact of institutional environments on operation mode, in that private governance may substitute for public governance that country institutions confer. This is to highlight the distinctive role of governance capability for modern multinationals in generating advantages for the ecosystem they establish (Li et al., 2019).

The paper contributes to the literature on several fronts. First, in bridging the gap between platform research and internalization theory, we demonstrate how platforms, increasingly regarded as a hybrid form (Chen et al., 2022), fit the ongoing extensions of internalization theory that center on fragmented production and network relationships (Narula et al., 2019). We submit that instead of invoking hierarchies to overcome market failures (as MNEs would do), MNPs externalize non-core productive capabilities (e.g., content production) and deploy a non-integration organizational arrangement to recombine assets (Narula & Verbeke, 2015), an idea at the heart of modern internalization theory. Hence, we call for platform research to join force with the established IB literature in understanding contemporary multinationals. Second, we further conceptualize platforms as a distinct hybrid organization that enables resource deployment by transferring the right to exploit global users’ intellectual property to the platform firm. While recent internalization research has highlighted the divergence of MNEs’ decision rights from payoff rights (and ownership) (Chi & Zhao, 2014), we offer fresh insights by examining how platform firms obtain control over the use of externally owned, worldwide resources to generate economic rents. That unveils a new organizational mechanism for the ‘hub’ firm to exploit ‘ecosystem-specific advantages’ in the digital economy (Li et al., 2019), beyond what has been discussed in the quasi-internalization literature (Narula et al., 2019). Third, we enrich the institutional perspective in IB. Assuming MNEs are the IP owner, prior research has widely examined firms’ governance of deployment of proprietary resources in the host country (Oxley, 1999; Rugman et al., 2011; Santangelo, Meyer, & Jindra, 2016). Instead, we shed light on the impact of host-country IP protection on platform firms’ sourcing of and profiting from external resources, recasting platform firms as the ‘licensee’ in global markets. We provide a complementary lens to the received view that resources like intellectual property “confer value only if supported by a favorable property rights regime” (Verbeke, 2013: 6).

THEORIES

Internalization Theory and Trends of Externalization

IB as a field is largely built upon internalization theory, which explicates how the level of transaction costs for productive resources (e.g., intermediate products, knowledge, and distribution) determines the comparative efficiency of different organizational forms, and by extension, explains the raison d’etre of the MNE (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982). Transaction costs arise because writing and executing a reliable contract for the use of technology requires adequate specification of property rights and effective monitoring and enforcement of contractual terms (Coase, 1960). Such market imperfections become particularly salient in international markets where institutional environments (e.g., IPR regimes) can vary significantly from that of the home country (Zhao, 2006). An important assumption of the internalization thesis lies in proprietary resources, which are deemed “a sine qua non for the MNE” (Narula et al., 2019: 1233). That has led theorists to characterize firm-specific advantages as not only the focal unit of cross-border transactions but also a determinant of the organizational forms taken (Rugman & Verbeke, 1992).

Meanwhile, phenomena of modern MNEs, such as offshoring and outsourcing, global value chains (GVCs), and the ‘global factory’, have drawn growing attention to quasi-internalization or externalization as the rising mode of organization (Strange & Humphrey, 2019). Externalization increasingly refers to cases where the control boundary of the firm diverges from its ownership boundary (Narula et al., 2019), including a myriad of organizational forms (Narula, 2001). As Liesch et al., (2012: 15) summarize, the scale and scope of MNEs’ cross-border economic activities may become a question of involvement rather than investment, to the extent that we need “a complementary explanation to internalization theory” for disaggregated value-creating activities that characterize modern MNEs. Various ways of involvement (i.e., externalization) may be driven by value-creating considerations (e.g., in accessing others’ productive capabilities), instead of the sole logic of cost minimization (Martínez-Noya & Narula, 2018). In line with this trend, IB scholars have advanced the idea of ‘ecosystem-specific advantages’ in accounting for digital platform firms’ utilization of external resources in international markets (Li et al., 2019).

Hybrids and Property Rights

There is an increasing appreciation in IB that externalization can generate economic value by tapping into productive capabilities held by other agents (Jacobides & Hitt, 2005; Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009), and that MNEs could be specialized in externalization rather than internalization (Narula et al., 2019). Much discussion has revolved around the constellation of various organizational forms for accessing external capabilities in foreign markets (Narula, 2001). One important insight is that externalization is not always ‘the market’ but could be a rich variety of hybrid organizational forms (Williamson, 1991), or as Hennart (1993) calls them, ‘the swollen middle’. Hybrids involve “legally autonomous entities doing business together … and sharing or exchanging technologies, capital, products and services, but without a unified ownership” (Ménard, 2004: 160). Such interfirm relationships are only weakly contractualized, and the linkages are rooted in technological complementarities or organizational synergies (Thorelli, 1986). Hybrids may be an optimal mode when markets are perceived as unable to adequately bundle the relevant resources and capabilities (Teece & Pisano, 1994) and when integration would otherwise reduce flexibility by creating irreversibility and weakening incentives (Tong & Reuer, 2007).

IB scholars have discussed extensively relational contracting as an exemplary form of externalization, as opposed to arm’s length dealings (Kano, 2018).2 An often-understated aspect of hybrids is the precise mechanisms for allocating resources in hybrids, a prominent one being property rights (Cuypers, Hennart, Silverman, & Ertug, 2021). Narula et al., (2019: 1245) note in passing that quasi-internalized MNEs can exert significant control over external partners “through effective means of partitioning and enforcing the property rights to the operations”. In fact, there is an inherent link with hybrids in property rights theory, an intellectual cousin of internalization theory that derives, too, from Coase (1960).3 Hybrids can be seen as arrangements in which two or more partners pool or transfer strategic decision rights, while simultaneously retaining distinct ownership over key resources, so that they require specific devices to coordinate their joint activities and arbitrate the allocation of payoffs (Ménard, 2004).

Taking this idea forward, organization theorists have recasted firm resources as bundles of property rights (Kim & Mahoney, 2010). Property rights sanction the behavioral relations among decision-makers in the use of potentially valuable resources (Foss & Foss, 2005; Kim & Mahoney, 2002). As with any other property rights, private ownership of intangible resources, such as intellectual property, is not a monolithic right granted to one individual, but involves a range of privileges, including the decision rights to exclude non-owners from access, to use and change the form of the resource, and to sell or transfer the resource to others, as well as the payoff rights to appropriate rents from use of and investments in the resource (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972; Libecap, 1989).4 Property rights theory presents a useful theoretical lens to understand de facto resource ownership, i.e., how firms employ resources nested beyond their legal boundaries (Santos & Eisenhardt, 2005). That is key to examining economic value jointly created by a complex network of partners (Klein, Mahoney, McGahan, & Pitelis, 2012), such as in the case of platforms.

Platforms as a New Hybrid Organizational Form

Platforms are a typical example of externalization as they divest non-core, generic activities and focus on core competences that can maximize organizational value so as to attain economies of co-specialization—a point well made by Banalieva and Dhanaraj (2019) but also related broadly to modern MNEs (Kedia & Mukherjee, 2009).5 Internalization research has attributed the adoption of externalization to worldwide markets for market transactions (Liesch et al., 2012), distribution of specialized competences across firms (Narula, 2001), and firms’ capabilities for coordinating external relationships (Lee, Narula, & Hillemann, 2021). In our view, platforms represent an alternative form of externalization that arises because digital technology and modular architecture can much facilitate exchange relationships.6

Specifically, why organizing as a platform (instead of arm’s length dealings or hierarchies)? The choice of a specific organizational form depends on “the anticipated complexity of decomposing tasks among partners and of coordinating across organizational boundaries” (Gulati & Singh, 1998: 782). On the one hand, the modular architecture underlying platforms promotes division of labor because of low costs of ‘unbundling’ operations (Baldwin & Woodard, 2009), similar to what underpins fragmented production in GVCs (Elia, Massini, & Narula, 2019). On the other hand, productive capabilities and the resulting modular innovations (produced by external partners) are recombined ex post by platform customers to suit their own heterogeneous needs, rather than internally by the firm (Yoo, Boland, Lyytinen, & Majchrzak, 2012), thereby ruling out integration as the predominant mode of organization. IB researchers have sought to understand the specific form of externalization underlying platform ecosystems (Chen et al., 2019). Given the premise that locally sourced complementary resources are crucial to an MNP’s value creation in a host country (Stallkamp & Schotter, 2021), scholars frame both the resource position contributed by local complementors and the platform firm’s orchestration as key components of ‘ecosystem-specific advantages’ for MNPs (Li et al., 2019).

While it appears that platform organization enables the trading of the use of local complementary resources in a similar way as depicted in the traditional bundling model of foreign entry (Hennart, 2009), it in fact departs notably from transactions in a factor market. First, because of bounded rationality, traditional market transactions are made untenable. There is significant market uncertainty over what local complementary resources should be contracted for and at what level to price them.7 For instance, IP owners (e.g., mobile game developers) and potential ‘licensees’ (e.g., Apple and Google) have little a priori knowledge of how much a locally produced game would be worth for both local and global smartphone users. Second, contracting involves high levels of rigidity; that renders it too costly to continuously refine a contract in encapsulating all ex post adaptations (e.g., updates on game features) (Chen, Wang, et al., 2021; Chen, Yi, et al., 2021; Chen, Zhang, et al., 2021), suggesting irremediable market failures in eliciting services of external productive capabilities.8 As opposed to trading in a local factor market, platforms constitute a unique non-integration organizational form that, in light of uncertainty, can economize on ex ante bounded rationality and facilitate ex post adaptations (Chen et al., 2022). As a plethora of legally autonomous actors put themselves under informal authority of the platform firm, “adaptations can be made...without the need to consult, complete, or revise interfirm agreements” (Williamson, 1979: 253).9 This is much in line with how hybrids are defined (Williamson, 1991).

Following the property rights perspective (Libecap, 1989), we could argue that platforms institute the use of external resources by enabling exchanges of bundles of decision rights in realizing economies of co-specialization. Platform owners transfer to local complementors bundles of property rights to the platform resources, such as the platform interface and development toolkits. These primarily include the decision rights to develop complementary products independently as enabled by the platform technology, and to distribute those products to platform customers (local and abroad), as well as the rights to capture a share of the resulting payoffs. In return, platform owners may obtain some decision rights to the use of local complementors’ resources (including the right to prohibit unauthorized access and use by others) and payoff rights. Instead of negotiating the price of an IP with a licensor (i.e., complementor) ex ante, platform owners share ex post payoffs from utilizing the IP. The ‘price’ paid to the IP owner partly depends on market performance (an element of market incentives), and is under the platform firm’s hierarchical control as it can adjust, on an ongoing basis, data traffic at its discretion (an element of hierarchies).10

To further our understanding of MNPs’ international operations, we use social platforms as an example to explore their operation mode under varying institutional environments. We take two inspirations from classic theories. First, ownership of a resource refers to ownership of certain property rights to that resource, and property rights should belong to the party with the economic incentive and ability to maximize utilization of the resource (Coase, 1960). Second, the initial assignment of decision rights, as well as the expected distribution of payoffs, will influence ex ante investments of complementors (Hart & Moore, 1990). Unlike market transactions, transfer of decision rights does not involve contingent claim contracts that fully describe complementors’ responsibilities and rights for future contingencies (Kim & Mahoney, 2005). It instead relies on rights reallocation by the platform firm that can create appropriate economic incentives for ‘owners’ of each bundle of rights (Tiwana et al., 2010). We develop propositions based on these two fundamental ideas.

Social Platforms and Institutional Environments

Platforms create value by reducing frictions and barriers that would otherwise inhibit users from exchanging with one another (Zhu & Iansiti, 2012). Social platforms constitute one of the predominant categories of digital platforms (Cennamo, 2021). The very value of social platforms lies in facilitating and channeling users’ expression of ideas, often through audio-visual or image content creations (i.e., UGC). The fact that most contents created on a social platform are intangible and their value is hard to assess renders it an intriguing organizational form substituting for traditional factor markets. Research shows that complementors’ ability to appropriate returns from their innovation depends on their ownership of formal IPR (Ceccagnoli, Forman, Huang, & Wu, 2012; Huang, Ceccagnoli, Forman, & Wu, 2013). The major type of IPR in social platforms is copyrights, which protect original work of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.11

Like other types of IPR, copyrights only have monetary value when exploited to produce some economic benefit for the owner. Copyright owners can exploit UGC given their right to grant a license to reproduce, distribute, perform, or display the copyrighted work to the public and obtain a royalty for granting the right (Besen & Raskind, 1991). On the one hand, a significant amount of productive capabilities (i.e., human capital) in social platforms tend to be inalienable (i.e., must remain in the control of heterogeneous complementors to generate most value), leading the platform to rely on complementors’ specific investment in developing original and valuable informational content. On the other hand, platforms’ specific investments pave the very ground for UGC and its exploitation; the servers and interfaces provided by the platform are necessary for content creation and posting (OECD, 2007). That gives the platform firm rights to use and change the form of user contributions and to earn the resulting incomes (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972). In practice, the platform firm often imposes mandatory terms of copyright sharing and complimentary licensing in return for giving users platform access. As the Facebook Terms of Service unequivocally states:12

By posting User Content to any part of the Site, you automatically grant... to the Company an irrevocable, perpetual, non-exclusive, transferable, fully paid, worldwide license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, publicly perform, publicly display, reformat, translate, excerpt (in whole or in part) and distribute such User Content for any purpose, commercial, advertising, or otherwise, on or in connection with the Site or the promotion thereof, to prepare derivative works of, or incorporate into other works, such User Content, and to grant and authorize sublicenses of the foregoing.

While users retain de jure ownership right to the original content they create, platform firms can deploy UGC for advertising and third-party consumption from which to accrue their own payoffs (Sun & Zhu, 2013). This is because, in Teece’s (2014) terms, platform owner’s proprietary ownership of the critical productive resource renders complementors dependent on the platform in commercializing their innovations.

Despite the born-global nature of many social platforms, the platform literature in general, and our understanding of social platforms in particular, have yet to fully incorporate IB insights. IB scholars have long examined the impact of local institutional deficiencies on MNE boundary (e.g., Santangelo et al., 2016). Following this tradition, we focus on IPR regimes given that the contents shared on social platforms – a core component of ‘ecosystem-specific advantages’ – are copyright protected and closely affected by the formal IPR environment. We link our conceptualization to the fundamental question of IB research and internalization theory (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017): what determines organizational boundary in international expansion.

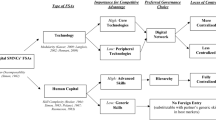

First, following Teece (2014), we consider how the level of dependence of complementors on platform owners may vary with the strength of IPR regimes, which in turn will affect social platforms’ boundary in externalizing content production in a country. Classic theory maintains that in response to changes in the external environment, property rights will be reassigned to the party who can generate greater economic value from utilizing that bundle of property rights (Coase, 1960; Demsetz, 1967). In institutional environments where the formal IPR regime is weak, copyright owners (i.e., content creators) face heightened appropriability hazards in the IP market and substantial transaction costs of going on the market on their own (Liebeskind, 1996), since few customers would pay to access unprotected content. Given that platform firms occupy the nexus of multilateral relationships (Boudreau & Hagiu, 2009), they have significant information advantage regarding how to best appropriate the value of the UGC, where to induce value-creating derivative use, and to whom to transfer rights to further commercialize the UGC. Those information processing competences allow platform owners to direct resources efficiently in such an institutional environment (Alchian & Demsetz, 1972). Therefore, copyright owners will accede to the direction and restriction of a ‘central coordinator’ because of the expected gains from this efficient coordination (Broekhuizen, Lampel, & Rietveld, 2013), turning themselves into complementors for a platform and particularly for an MNP that imposes more stringent IP protection.13 Conversely, from the platform owners’ viewpoint, they are subject to significant appropriability hazards should they choose to offer proprietary content in a weak IP environment.14 For example, local rival platforms (and their users) may port content from MNPs and generate revenue without the latter’s consent and without them even knowing it. Facing uncertain returns to R&D due to potential IP infringement, they would rather ‘delegate’ content creation to third-parties and share profits ex post. Because copyrights are enforced through costly litigation for individual IP owners (Liebeskind, 1996; Besen & Raskind, 1991) and because of economies of co-specialization, externalizing content production (i.e., non-core activities) tends to be the default mode of operation for social platforms.

Yet, as IPR regimes improve, copyright owners (i.e., complementors) will benefit from reduced transaction costs in trading the use of UGC in the factor market. Because of attenuated appropriability hazards, they can engage in efficient bargaining by delineating in a contract what utilizations are permitted with the UGC they create. Establishing, enforcing, and profiting from IPR no longer relies on significant investment by the platform firm, resulting in its diminished ability to claim rights to make value-creating and payoff-relevant decisions associated with UGC. On the other hand, platform firms also face reduced appropriability hazards in exploiting their proprietary content, from which their distinct market positioning, and by extension, competitive advantage can accrue (Cennamo, 2021). Therefore, we expect IPR regimes to shape MNPs’ mode of operation. In weaker IPR regimes, social platforms will more likely and more extensively externalize content production to complementors. As IP protection strengthens, social platforms will be more willing to increase the level of internalization and produce more platform proprietary content.

Proposition 1:

The formal IPR environment in a host country affects social platforms’ operation mode, such that the level of internalization in content production will increase as the IPR regime improves.

While we submit that public institutions in a host country shape the willingness of both platform owners and complementors to collaborate (i.e., externalization), underlying our theory is the premise that platform owners have a certain degree of capability to maintain complementors’ investment incentives despite institutional deficiencies and appropriability hazards. Prior research suggests that MNEs tapping into external innovative talents can rely on internal organization to sidestep appropriability hazards in weak IP countries (Zhao, 2006). Drawing upon this view and the more recent account of ecosystem governance (Li et al., 2019), we argue that the capability of governing the ecosystem may partially substitute for the role of host-country public institutions in determining an MNP’s internalization.

We define governance capability as a firm’s capacity to efficiently orchestrate value-creating activities of (external) resources on which it can exert some degree of control and from which it can generate economic rents. Platform owners assume the role of governing the ecosystem given their ownership of the platform technology (Chen et al., 2022). Building on the platform governance literature, we argue that governance capabilities are critical for MNPs on three fronts. First, governance by the ‘hub’ firm establishes ecosystem rules, to the extent that MNPs can implement ecosystem-specific norm of IPR appropriation in utilizing external resources. For instance, YouTube deploys a digital fingerprinting system called Content ID allowing complementors to block copyright-infringed contents or otherwise claim revenues earned by those contents. Stronger enforcement of IP reduces the level of appropriability hazards complementors face in comparison to rival platforms or IP markets. The ability to establish personal IP (and a loyal fanbase) on the focal MNP will enhance complementors’ ex ante investment incentives. In this regard, private governance of the ecosystem overshadows the level of public institutional development (Boudreau & Hagiu, 2009), at least in determining operation mode.

Second, governance regulates the interaction among complementors. Governance capabilities determine whether the platform firm is able to nurture an environment that is conducive to original content creation. The cost of content creation depends on the extent to which users can borrow from, or build on, earlier works which may well be copyright protected (Besen & Raskind, 1991). Holding decision rights to contents created around the world, MNPs may facilitate local content contributions by allowing complementors to build on those user-generated or licensed works that are otherwise copyright protected (Nagaraj, 2018). For instance, TikTok makes available to content creators a tremendous library of popular music tracks, free of cost, for them to use in their video clips. Doing so enables complementors to continuously produce high-quality new content at a high pace, a prominent appropriability strategy in its own right (Chen, Zhang, Li, & Turner, 2021; Miric, Boudreau, & Jeppesen, 2019).

Third, governance helps shape the relationship between complementors and other ecosystem participants. MNPs with high levels of governance capabilities may reallocate decision rights favorably such that complementors can obtain more control over how to commercialize their content on the platform, along with favorable distribution of payoff rights for complementors (Sun & Zhu, 2013). For example, TikTok boasts a Creator Marketplace providing analytics-based information to match global influencers with ad sponsors, while Instagram has introduced Creator Shops turning an influencer’s Facebook and Instagram pages into online storefronts so that her followers can purchase products in the affiliate e-commerce marketplace seamlessly. The former enables TikTok creators to customize and set prices for their UGC (i.e., greater decision rights). The latter allows Instagram influencers to take a cut of the sales of the products they recommend (i.e., greater payoff rights). These will strengthen complementors’ ex ante willingness to make platform-specific investment, weakening the impact of market failures and public institutions.

In extending the idea of ‘ecosystem-specific advantages’ (Li et al., 2019), we submit that platform owners’ governance capabilities can strengthen the incentives of complementors’ resource contributions, and enable MNPs to maximize the utilization of, and profit from, externally owned resources. In so doing, they help enhance the value created by an MNP without incurring the production cost associated with proprietary contents. Hence, strong governance capabilities may overpower the influence of host-country IPR regimes on an MNP’s degree of externalization.

Proposition 2:

Social platforms with stronger governance capabilities are less likely to be affected by host-country IPR regimes in determining operation mode (i.e., the level of internalization).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this paper, we draw on hybrids research and property rights theory to complement the internalization school in accounting for platform organization, which has attracted growing attention from IB scholars. Our conceptual analysis centers on the organizational mechanisms of platforms. Using social platforms as an example, we develop propositions regarding the impacts of institutional protection and governance capabilities on MNPs’ operation mode. As a result, we contribute to the literature in three aspects.

First, we advance the IB debate on platforms. While some scholars have suggested that network-based platform organizations represent a distinctly new organizational form that is unaccounted for by conventional theory (Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2019), others argue that platforms are much in line with hybrids (Hennart, 2019). Recent platform research has more explicitly suggested a link between platforms and hybrids (Chen et al., 2022; Kretschmer, Leiponen, Schilling, & Vasudeva, 2020). We further develop this view and stress that platforms, as with many other hybrid forms, transfer decision rights (and payoff rights) across fixed firm boundaries. They rely on “partners who maintain distinct property rights and remain independent claimants” (Ménard, 2004: 351) but become affiliated with the same ecosystem without formal contractual relations (Gulati, Puranam, & Tushman, 2012). Prior IB research on hybrids has primarily focused on shared equity ownership in a firm (e.g., international joint ventures), while a resource is deemed the irreducible unit of analysis – it is either traded on the market or internalized. Drawing on the property rights perspective, we instead direct attention to firms’ rights to use a resource, an idea that can be traced back to Penrose (1959), and we unveil the specific mechanism of property rights exchange that underpins the division of labor in inter-firm collaboration (Gulati et al., 2012). We submit that the decades of hybrids research in IB and beyond will continue to offer substantial inspirations for the MNP literature going forward.

Second, we nest our renewed conceptualization of platforms in the broader efforts to extend internalization theory. Internalization theory has been developed and applied by generations of IB researchers to suit contemporary organizational phenomena. Recent development shows a growing appreciation of externalization or quasi-internalization that characterizes disaggregated value chain activities (Narula et al., 2019). The main thesis centers on MNEs’ sphere of influence that exceeds beyond their legal boundary, in that modern MNEs can coordinate external productive capabilities using de facto control without resorting to de jure ownership of the assets (Chi & Zhao, 2014). While the retreat of firms’ ownership boundary echoes the case of platforms (e.g., Airbnb often noted as “the world’s largest accommodation provider owning no real estate”), our conceptualization takes one step further than extant research which attributes externalization mainly to the ‘hub’ firm’s behavioral control of partners (Kano, 2018; Teece, 2014). We elucidate how digital technologies and platform organization enable firms to obtain and reallocate decision and payoff rights to externally owned resources, and as a result, orchestrate a value-creating ecosystem that span national borders.

Finally, our conceptualization leads to testable propositions that can yield new insights for institutional research in IB. IB research has long taken for granted that MNEs are the IP owner and thus paid much attention to firms’ governance of deployment of proprietary resources in the host country (e.g., Santangelo et al., 2016). In contrast to the received wisdom that MNEs rely on hierarchical governance in weak IP institutions to prevent unwanted rent dissipation (Oxley, 1997; Rugman et al., 2011), we argue that institutional deficiencies are in favor of externalization by MNPs. On the other hand, much neglected is the fact that platform firms, even Facebook, may themselves be the owner of proprietary IP (‘Site Content’ as in Facebook’s Terms of Service) (Zhang & Sarvary, 2015). We maintain that in strong IPR regimes, legal protection of copyrights may serve as an isolating mechanism increasing the platform’s capacity to exploit proprietary resources and the extent of internalization. Furthermore, in recognizing the substitutive relationship between private and public governance, we highlight the critical role of governance capabilities for ‘hub’ firms to establish and exploit ‘ecosystem-specific advantages’. Our conceptual arguments lead to the view that stronger capabilities may render an MNP more efficient in utilizing external resources and less prone to adjust operation mode as institutional protection changes. This is consistent with the prior finding that MNEs can utilize internal organization to counter the appropriability hazards in the external environment when performing innovation activities in weak institutions (Zhao, 2006).

While our theory of MNPs draws on the classic property rights perspective and should be generalizable beyond the current context, how different categories of platforms (e.g., exchange platforms and innovation platforms) may introduce specific boundary conditions remains to be examined. One might also wonder if and the extent to which strong capabilities could help MNPs internalize content production in weak IPR regimes owing to their improved ability to manage and protect copyrights. We encourage IB scholars to continue this inquiry empirically by, for instance, comparing the extent of proprietary content production by an MNP in different major markets, or the changes of operation mode by rival MNPs in a given market where an abrupt change in public institutions is introduced.

Notes

-

1

We use the label ‘internalization theory’ to refer to a broadly defined paradigm given that different incarnations of the theory share “a common set of principles and epistemology” (Narula et al., 2019: 1232).

-

2

That echoes a conceptual transition in institutional economics that drifts away from the mechanical details of how production is arranged (i.e., internal vs. external) toward a focus on how the relationships between production partners are governed (Milgrom & Roberts, 2009).

-

3

Property rights theory shows broad consistency with internalization theory in at least two aspects: the definition of integration as the unification of control, and the focus on contract imperfections as a necessary condition for integration to matter (Gibbons, 2005).

-

4

This is consistent with internalization theory where market-vs.-hierarchy is essentially a means to transfer control over some attributes of a resource from the resource owner to another party who values the resource most. However, extant research on hybrids, such as alliances, has much more to say about shared ownership in a firm rather than of a resource. In understanding property rights partitioning that underpins platforms, we focus specifically on the transfer of decision rights to use or appropriate rents from a resource.

-

5

That seems to suggest an inherent but understated connection between the nascent platform literature and the more established view of externalization in IB.

-

6

We acknowledge that this paper focuses on digital platforms while other types of platform organizations such as shopping malls and open innovation centers are also prominent hybrid forms. We thank a Reviewer for this insight.

-

7

Such uncertainty has inspired the view that complements may have optionality value for the platform firm who has little a priori knowledge about what to ‘buy’ or ‘make’ in complementary markets (Toh & Agarwal, 2020).

-

8

Under non-integration, the platform firm would have to sign elaborate contracts with each complementor for producing complements that are determined and agreed upon ex ante, a situation that is rather untenable because of market uncertainty and bounded rationality and may lead to collectively inefficient haggling ex post (Williamson, 1985).

-

9

By contrast, traditions of internalization theory often attribute market imperfections to Coasian transaction costs, Arrow’s information paradox, and opportunism.

-

10

For example, Amazon unilaterally directed data traffic away from high-performing complementary products in attempts to improve value capture and effectively reduce the ‘price’ paid to those contributing complementors (Zhu & Liu, 2018).

-

11

Contrary to patents for which property right claims are specified ex ante, copyrights exist independently of prior registration. For instance, the photographs that a user takes and uploads to a social platform are, without any action on her part, regarded as intellectual property.

-

12

All other major social platforms share almost identical Terms of Services in this regard.

-

13

While complementors may enjoy the agency to switch to an alternative platform ex post, they are often constrained by small numbers bargaining due to network externalities and by any platform-specific investment incurred (Chen, Yi, Li, & Tong, 2021; Hennart, 2019), which increase the switching cost.

-

14

In the landmark lawsuit between Viacom and YouTube, Viacom, a media company publishing proprietary content, accused YouTube of promoting rampant infringement in its ‘original’ UGC and alleged that the widespread availability of such infringing content “is the cornerstone of [YouTube’s] business plan.” This is indicative of the appropriability hazards for proprietary content when IP protection is insufficient.

REFERENCES

Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. 1972. Production, information costs, and economic organization. American Economic Review, 62(5): 777–795.

Baldwin, C. Y., & Woodard, C. J. 2009. The architecture of platforms: A unified view. In A. Gawer (Ed.), Platforms, markets and innovation Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Banalieva, E. R., & Dhanaraj, C. 2019. Internalization theory for the digital economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8): 1372–1387.

Besen, S. M., & Raskind, L. J. 1991. An introduction to the law and economics of intellectual property. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1): 3–27.

Boudreau, K. J., & Hagiu, A. 2009. Platform rules: Multi-sided platforms as regulators. In A. Gawer (Ed.), Platforms, markets and innovationCheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Broekhuizen, T. L. J., Lampel, J., & Rietveld, J. 2013. New horizons or a strategic mirage? Artist-led-distribution versus alliance strategy in the video game industry. Research Policy, 42(4): 954–964.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. 1976. The future of the multinational enterprise. London: Homes & Meier.

Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. 2017. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1045–1064.

Ceccagnoli, M., Forman, C., Huang, P., & Wu, D. J. 2012. Cocreation of value in a platform ecosystem: The case of enterprise software. MIS Quarterly, 36(1): 263–290.

Cennamo, C. 2021. Competing in digital markets: A platform-based perspective. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(2): 265–291.

Chen, L., Shaheer, N., Yi, J., & Li, S. 2019. The international penetration of ibusiness firms: Network effects, liabilities of outsidership and country clout. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(2): 172–192.

Chen, L., Tong, T. W., Tang, S., & Han, N. 2022. Governance and design of digital platforms: A review and future research directions on a meta-organization. Journal of Management, 48(1): 147–184.

Chen, L., Wang, M., Cui, L., & Li, S. 2021a. Experience base, strategy-by-doing and new product performance. Strategic Management Journal, 42(7): 1379–1398.

Chen, L., Yi, J., Li, S., & Tong, T. W. 2021b. Platform governance design in platform ecosystems: Implications for complementors' multihoming decision. Journal of Management, in press.

Chen, L., Zhang, P., Li, S., & Turner, S. F. 2021c. Growing pains: The effect of generational product innovation on mobile games performance. Strategic Management Journal, in press.

Chi, T., & Zhao, Z. J. 2014. Equity structure of MNE affiliates and scope of their activities: Distinguishing the incentive and control effects of ownership. Global Strategy Journal, 4(4): 257–279.

Coase, R. H. 1960. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 56(4): 1–13.

Cuypers, I., Hennart, J.-F., Silverman, B., & Ertug, G. 2021. Transaction cost theory: Past progress, current challenges, and suggestions for the future. Academy of Management Annals, 15(1): 111–150.

Demsetz, H. 1967. Toward a theory of property rights. American Economic Review, 57(2): 347–359.

Dunning, J. H. 1988. The eclectic paradigm of international production: A restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(1): 1–31.

Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. 2008. Multinational enterprises and the global economy (2nd ed.). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Elia, S., Massini, S., & Narula, R. 2019. Disintegration, modularity and entry mode choice: Mirroring technical and organizational architectures in business functions offshoring. Journal of Business Research, 103: 417–431.

Foss, K., & Foss, N. J. 2005. Resources and transaction costs: How property rights economics furthers the resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 26(6): 541–553.

Gibbons, R. 2005. Four formal(izable) theories of the firm? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 58(2): 200–245.

Gulati, R., Puranam, P., & Tushman, M. 2012. Meta-organization design: Rethinking design in interorganizational and community contexts. Strategic Management Journal, 33(6): 571–586.

Gulati, R., & Singh, H. 1998. The architecture of cooperation: Managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4): 781–814.

Hart, O., & Moore, J. 1990. Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6): 1119–1158.

Hennart, J.-F. 1982. A theory of multinational enterprise. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hennart, J.-F. 1993. Explaining the swollen middle: Why most transactions are a mix of “market” and “hierarchy.” Organization Science, 4(4): 529–547.

Hennart, J.-F. 2009. Down with MNE-centric theories! Market entry and expansion as the bundling of MNE and local assets. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9): 1432–1454.

Hennart, J.-F. 2019. Digitalized service multinationals and international business theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8): 1388–1400.

Huang, P., Ceccagnoli, M., Forman, C., & Wu, D. J. 2013. Appropriability mechanisms and the platform partnership decision: Evidence from enterprise software. Management Science, 59(1): 102–121.

Jacobides, M. G., & Hitt, L. M. 2005. Losing sight of the forest for the trees? Productive capabilities and gains from trade as drivers of vertical scope. Strategic Management Journal, 26(13): 1209–1227.

Kano, L. 2018. Global value chain governance: A relational perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(6): 684–705.

Kedia, B. L., & Mukherjee, D. 2009. Understanding offshoring: A research framework based on disintegration, location and externalization advantages. Journal of World Business, 44(3): 250–261.

Kim, J., & Mahoney, J. T. 2002. Resource-based and property rights perspectives on value creation: The case of oil field unitization. Managerial and Decision Economics, 23(4–5): 225–245.

Kim, J., & Mahoney, J. T. 2005. Property rights theory, transaction costs theory, and agency theory: An organizational economics approach to strategic management. Managerial and Decision Economics, 26(4): 223–242.

Kim, J., & Mahoney, J. T. 2010. A strategic theory of the firm as a nexus of incomplete contracts: A property rights approach. Journal of Management, 36(4): 806–826.

Klein, P. G., Mahoney, J. T., McGahan, A. M., & Pitelis, C. N. 2012. Who is in charge? A property rights perspective on stakeholder governance. Strategic Organization, 10(3): 304–315.

Kretschmer, T., Leiponen, A., Schilling, M., & Vasudeva, G. 2020. Platform ecosystems as metaorganizations: Implications for platform strategies. Strategic Management Journal, in press.

Lee, J. M., Narula, R., & Hillemann, J. 2021. Unraveling asset recombination through the lens of firm-specific advantages: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of World Business, 56(2): 101193.

Li, J., Chen, L., Yi, J., Mao, J., & Liao, J. 2019. Ecosystem-specific advantage in international digital commerce. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9): 1448–1463.

Libecap, G. D. 1989. Contracting for property rights. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Liebeskind, J. P. 1996. Knowledge, strategy, and the theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2): 93–107.

Liesch, P. W., Buckley, P. J., Simonin, B. L., & Knight, G. 2012. Organizing the modern firm in the worldwide market for market transactions. Management International Review, 52(1): 3–21.

Martínez-Noya, A., & Narula, R. 2018. What more can we learn from R&D alliances? A review and research agenda. Business Research Quarterly, 21(3): 195–212.

Ménard, C. 2004. The economics of hybrid organizations. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 160(3): 345–376.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. 2009. Bargaining costs, influence costs, and the organization of economic activity. In L. Putterman, & R. S. Kroszner (Eds.), The economic nature of the firm: A reader: (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miric, M., Boudreau, K. J., & Jeppesen, L. B. 2019. Protecting their digital assets: The use of formal & informal appropriability strategies by app developers. Research Policy, 48(8): 103738.

Nagaraj, A. 2018. Does copyright affect reuse? Evidence from Google books and Wikipedia. Management Science, 64(7): 3091–3107.

Narula, R. 2001. Choosing between internal and non-internal R&D activities: Some technological and economic factors. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 13(3): 365–387.

Narula, R., Asmussen, C. G., Chi, T., & Kundu, S. K. 2019. Applying and advancing internalization theory: The multinational enterprise in the twenty-first century. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8): 1231–1252.

Narula, R., & Verbeke, A. 2015. Making internalization theory good for practice: The essence of Alan Rugman’s contributions to international business. Journal of World Business, 50(4): 612–622.

OECD. 2007. Participative web and user-created content: Web 2.0, Wikis and social networking: OECD.

Oxley, J. E. 1997. Appropriability hazards and governance in strategic alliances: A transaction cost approach. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 13(2): 387–409.

Oxley, J. E. 1999. Institutional environment and the mechanisms of governance: The impact of intellectual property protection on the structure of inter-firm alliances. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 38(3): 283–309.

Penrose, E. T. 1959. A theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 1992. A note on the transnational solution and the transaction cost theory of multinational strategic management. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(4): 761–771.

Rugman, A. M., Verbeke, A., & Nguyen, Q. T. K. 2011. Fifty years of international business theory and beyond. Management International Review, 51(6): 755–786.

Santangelo, G. D., Meyer, K. E., & Jindra, B. 2016. MNE subsidiaries’ outsourcing and insourcing of R&D: The role of local institutions. Global Strategy Journal, 6(4): 247–268.

Santos, F. M., & Eisenhardt, K. M. 2005. Organizational boundaries and theories of organization. Organization Science, 16(5): 491–508.

Stallkamp, M., & Schotter, A. P. J. 2021. Platforms without borders? The international strategies of digital platform firms. Global Strategy Journal, 11(1): 58–80.

Strange, R., & Humphrey, J. 2019. What lies between market and hierarchy? Insights from internalization theory and global value chain theory. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(8): 1401–1413.

Sun, M., & Zhu, F. 2013. Ad revenue and content commercialization: Evidence from blogs. Management Science, 59(10): 2314–2331.

Teece, D., & Pisano, G. 1994. The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(3): 537–556.

Teece, D. J. 2014. A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1): 8–37.

Thorelli, H. B. 1986. Networks: Between markets and hierarchies. Strategic Management Journal, 7(1): 37–51.

Tiwana, A., Konsynski, B., & Bush, A. A. 2010. Platform evolution: Coevolution of platform architecture, governance, and environmental dynamics. Information Systems Research, 21(4): 675–687.

Toh, P. K., & Agarwal, S. 2020. The optionality in complements within platform-based ecosystems. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2020(1): 15194.

Tong, T. W., & Reuer, J. J. 2007. Real options in multinational corporations: Organizational challenges and risk implications. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2): 215–230.

Verbeke, A. 2013. International business strategy: Rethinking the foundations of global corporate success (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Verbeke, A., & Hutzschenreuter, T. 2021. The dark side of digital globalization. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(4): 606–621.

Williamson, O. E. 1979. Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2): 233–261.

Williamson, O. E. 1985. The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. 1991. Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(2): 269–296.

Yoo, Y., Boland, R. J. J., Lyytinen, K., & Majchrzak, A. 2012. Organizing for innovation in the digitized world. Organization Science, 23(5): 1398–1408.

Zhang, K., & Sarvary, M. 2015. Differentiation with user-generated content. Management Science, 61(4): 898–914.

Zhao, M. 2006. Conducting R&D in countries with weak intellectual property rights protection. Management Science, 52(8): 1185–1199.

Zhu, F., & Iansiti, M. 2012. Entry into platform-based markets. Strategic Management Journal, 33(1): 88–106.

Zhu, F., & Liu, Q. 2018. Competing with complementors: An empirical look at Amazon.com. Strategic Management Journal, 39(10): 2618–2642.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to JIBS editor Rajneesh Narula and three anonymous reviewers for their excellent guidance. This research was supported by the University of South Carolina Center for International Business Education and Research (CIBER) grants, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 72091310, 72091312, 71902173, 71732008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Rajneesh Narula, Area Editor, 16 January 2022. This article has been with the authors for two revisions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Li, S., Wei, J. et al. Externalization in the platform economy: Social platforms and institutions. J Int Bus Stud 53, 1805–1816 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-022-00506-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-022-00506-w