Abstract

Although the study of family firm internationalization has generated considerable scholarly attention, existing research has offered varied and at times incompatible findings on how family ownership and management shape internationalization. To improve our understanding of family firm internationalization, we systematically review 220 conceptual and empirical studies published over the past three decades, structuring our comprehensive overview of this field according to seven core international business (IB) themes. We assess the literature and propose directions for future research by developing an integrative framework of family firm internationalization that links IB theory with conceptual perspectives used in the reviewed body of work. We propose a research agenda that advocates a cross-disciplinary, multi-theoretic, and cross-level approach to studying family firm internationalization. We conclude that family firm internationalization research has the potential to contribute valuable insights to IB scholarship by increasing attention to conceptual and methodological issues, including micro-level affective motivations, background social institutions, temporal perspectives, and multi-level analyses.

Résumé

Bien que l'internationalisation des entreprises familiales ait fait l’objet d’un intérêt de recherche considérable, les travaux existants apportent des résultats variés et parfois incompatibles sur la manière dont la propriété et la gestion familiales façonnent l'internationalisation. Dans le but d’améliorer notre connaissance de l'internationalisation des entreprises familiales, nous examinons systématiquement 220 travaux conceptuels et empiriques publiés au cours des trois dernières décennies, permettant de structurer notre aperçu complet sur ce champ selon sept thèmes clés des affaires internationales (IB - International Business). Nous évaluons la littérature, et proposons des orientations de recherche pour l’avenir en développant un cadre intégrateur de l'internationalisation des entreprises familiales, lequel relie la théorie IB aux perspectives conceptuelles utilisées dans l'ensemble des travaux examinés. Nous proposons un programme de recherche qui prône une approche transdisciplinaire, multi-théorique et multi-niveaux pour étudier l'internationalisation des entreprises familiales. Nous concluons que les travaux portés sur cette dernière ont le potentiel d'apporter des renseignements précieux au champ de recherche IB, en accordant une attention accrue aux problèmes méthodologiques et conceptuels, plus particulièrement, aux motivations affectives au niveau micro, aux institutions sociales de base, aux perspectives temporelles et aux analyses multi-niveaux.

Resumen

A pesar de que el estudio de la internacionalización de las empresas familiares ha provocado una considerable atención académica, las investigaciones existentes han ofrecido resultados heterogéneos y a veces incompatibles sobre la forma en que la propiedad y la gestión familiar configuran la internacionalización. Para mejorar nuestro entendimiento de la internacionalización de las empresas familiares, revisamos sistemáticamente 220 estudios conceptuales y empíricos publicados en las últimas tres décadas, estructurando nuestra amplia visión de este campo según siete temas centrales en negocios internacionales (IB por sus siglas en inglés). Evaluamos la bibliografía y proponemos orientaciones para futuras investigaciones mediante el desarrollo de un marco integrador de la internacionalización de la empresa familiar que vincula la teoría de negocios internacionales con las perspectivas conceptuales utilizadas en el conjunto de trabajos revisados. Proponemos una agenda de investigación que defiende un enfoque interdisciplinario, multi-teórico y a distintos niveles para estudiar la internacionalización de las empresas familiares. Llegamos a la conclusión de que la investigación sobre la internacionalización de las empresas familiares tiene el potencial de contribuir con valiosas ideas a los estudios de negocios internacionales al aumentar atención a los aspectos conceptuales y metodológicas, incluyendo las motivaciones afectivas a nivel micro, el contexto de las instituciones sociales, las perspectivas temporales y los análisis multi-nivel.

Resumo

Embora o estudo da internacionalização da empresa familiar tenha gerado considerável atenção acadêmica, a pesquisa existente ofereceu descobertas variadas, por vezes incompatíveis sobre como a propriedade e a administração familiar moldam a internacionalização. Para aprimorar nossa compreensão da internacionalização de empresas familiares, revisamos sistematicamente 220 estudos conceituais e empíricos publicados nas últimas três décadas, estruturando nossa visão abrangente desse campo de acordo com sete temas centrais de negócios internacionais (IB). Avaliamos a literatura e propomos direções para pesquisas futuras, desenvolvendo um modelo integrativo de internacionalização de empresas familiares que liga a teoria de IB com perspectivas conceituais usadas no corpo do trabalho revisado. Propomos uma agenda de pesquisa que defende uma abordagem interdisciplinar, multiteórica e multinível para estudar a internacionalização de empresas familiares. Concluímos que a pesquisa sobre internacionalização de empresas familiares tem o potencial de contribuir com percepções valiosas para a pesquisa em IB, aumentando a atenção a questões conceituais e metodológicas, incluindo motivações afetivas de nível micro, instituições sociais subjacentes, perspectivas temporais e análises multiníveis.

摘要

虽然对家族企业国际化的研究引起了学术界的广泛关注, 但现有研究对家族所有制和管理如何影响国际化有不同的且有时是不相容的发现。为了增进对家族企业国际化的了解, 我们系统地回顾了过去三十年中发表的220项理论和实证研究, 根据七个核心的国际商务 (IB) 主题构建了对该领域的全面概述。我们通过开发家族企业国际化的整合框架来评估文献并提出未来研究的方向, 该框架将IB理论与已评审的研究所使用的理论观点相联系。我们提出了一个研究议程, 提倡跨学科, 多理论和跨层次的方法来研究家族企业国际化。我们得出的结论是, 家族企业国际化研究有潜力通过增加对理论和方法论问题的关注对IB研究提供有价值的见识, 这里面包括微观层面的情感动机、背后的社会制度、时间观和多层分析。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Family firms dominate the business landscape. They employ about 60% of the global workforce and generate over half of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Family Firm Institute, 2017). Yet, family firms are not only important domestic producers: they are also prominent in international business (IB). The Economist (2015) predicts that the share of large multinational businesses owned or controlled by families will increase from about 15% to 40% by 2025. This trend is evident in Europe, where family companies like Ferrero and Michelin are important international players; in North America, with such companies as Walmart and Johnson & Johnson; in Australia, with Hancock Prospecting and Visy Industries; and in Asia, where examples include Hutchison Whampoa of Hong Kong, the Salim Group of Indonesia, and the Tata Group of India.

Although the prominence of family enterprise in the world economy has captured the interests of scholars across a variety of disciplines, IB scholars have been slow to embrace family business internationalization as a research field. In recent years, a broad consensus has emerged that family firms’ singular governance features shape their internationalization behavior. This potential uniqueness of family business internationalization has driven increased scholarly activity in this realm (Alayo, Iturralde, Maseda, & Aparicio, 2020; Debellis, Rondi, Plakoyiannaki, & De Massis, 2020b). Yet, IB scholars focus on traditional IB topics and assume that the influence of the controlling family on firm conduct is relatively homogeneous (Pukall & Calabrò, 2014). Meanwhile, family business scholars focus on family-driven phenomena and rarely explore questions motivated by IB theory. Moreover, existing research is highly heterogeneous, characterized by varied and often contrasting conceptual perspectives and definitions, and by diverse and incompatible measures (Arregle, Duran, Hitt, & van Essen, 2017). As a result, scholars struggle to access relevant research about how family ownership and management shape internationalization.

Extant reviews of family firms’ internationalization predominantly address the family business audience (e.g., Alayo et al., 2020; Casillas & Moreno-Menéndez, 2017; Kontinen & Ojala, 2010; Pukall & Calabrò, 2014), explore the evolution of the family firm internationalization literature (Debellis, De Massis, Petruzzelli, Frattini, & Del Giudice, 2020a), or focus on specific facets of family firm internationalization such as the internationalization process (e.g., Metsola, Leppäaho, Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, & Plakoyiannaki, 2020) and family SME internationalization (e.g., Lahiri, Mukherjee, & Peng, 2020). None specifically addresses the broad disciplinary needs of the IB audience.1 To accomplish this task, we offer a comprehensive review and assessment of the emerging field of international family business from an IB perspective. We review 220 conceptual and empirical articles on family business internationalization published in international academic journals through 2020. We organize and present these studies using IB themes – elements of international strategy that are common to most IB frameworks, and related to decisions about “the what, the where, and the how of internationalization” (Dunning & Kundu, 1995: 101). Hence, this review is IB-oriented but phenomenon-driven, and summarizes and articulates the theories used to understand internationalization in the context of family firms. Context has been a key element of IB research (Buckley & Lessard, 2005). In fact, attention to specific contexts (e.g., emerging/transition economies, see Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017; Hennart, 2012; Meyer & Peng, 2016; historical context, see Verbeke & Kano, 2015) has allowed researchers to refine and better understand the sensitivity of IB theories to their context. The family firm context has such potential.

After discussing our methodology in this review, we offer an overview of the family firm definitions employed in the reviewed studies. We then provide a comprehensive overview of the studies on family firm internationalization, organized according to seven key IB themes. We assess the literature, propose research opportunities, and discuss implications for both family firm internationalization and IB research as a whole. We believe that greater integration of IB concepts with the family firm internationalization literature, along with a stronger emphasis on the multilevel conceptual and empirical structure of family firm internationalization, will enrich the IB discipline while helping family firm scholars reconcile the many contradictions and conflicting perspectives found in this literature.

METHODOLOGY

Family firm internationalization is an emerging field of research, with contributions dispersed in multiple journals across different academic disciplines. Because the field is young and diverse, we chose to offer a systematic review of all relevant contributions (and not just those published in top-tier academic journals), starting with the very first academic articles published about family firm internationalization (i.e., Donckels & Fröhlich, 1991; Gallo & Sveen, 1991). Accordingly, we surveyed all academic journals with relevant articles on the topics of internationalization and/or family firms (Hoskisson, Chirico, Zyung, & Gambeta, 2017; Wan, Hoskisson, Short, & Yiu, 2011) for the period 1991 to 2020.2 We maintain that an inclusive approach is well suited for this emerging academic field, which, in its early years, lacked a constituency. Perhaps as a result of low interest, the topic was, at least initially, neglected by the top-tier journals, causing many early important contributions to find homes in less prestigious journals.3

We followed an established systematic review methodology, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (or PRISMA-P) (Shamseer et al., 2014) to execute our study. Specific steps undertaken include: (1) identifying the scope of the review (temporal boundaries and sources); (2) selecting keywords and conducting literature search; (3) screening identified studies for inclusion in the review; (4) assessing and coding studies; and (5) synthetizing findings and writing up the analysis. We detail these steps below.

We conducted a systematic search (Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, 2003) using keywords related to family firms and internationalization on five major electronic databases, including both discipline-specific (ABI/Inform database) and interdisciplinary databases (EBSCO database, Google Scholar, ISI Web of Knowledge, and Scopus).4 The initial search yielded 297 articles. Each identified paper was screened separately by at least two of the authors and an academic external to the authors’ team to ensure that it met our criterion for relevance. We eliminated 77 articles that casually mentioned family business or internationalization or did not specifically explore family governance and/or dimensions of IB as dependent or independent variables. The resulting 220 articles are reported in Appendix 1. For each article, we report key information, including source, theoretical frame, methodology, sample, family firm definition, key variables, and findings. Consistent with our claim that this is an emergent field, the majority (65%) of articles listed in Appendix 1 were published in the last 7 years.

We coded our 220 articles according to theories employed, research questions, and major topics of investigation. Then, we iteratively cross-referenced these articles with major IB-centric research questions related to the ‘what, where, and how’s’ of internationalization (Dunning, 1993; Dunning & Kundu, 1995). The iterative process yielded seven categories that play a central role in IB studies: (1) scale (or depth) of internationalization; (2) scope (or breadth) of internationalization; (3) international entry mode choice5; (4) international location choice; (5) internationalization process; (6) timing, or pace and rhythm of internationalization; and (7) internationalization performance. These seven categories, henceforth IB themes, encompass core phenomena addressed in the reviewed studies, but also represent key aspects of family firm internationalization decisions and outcomes (De Massis, Frattini, Majocchi, & Piscitello, 2018), as well as research themes that cut broadly across most IB frameworks (Verbeke, 2013).

We structured our review using these IB themes as our organizational frame. Three themes (scale, scope, and performance) represent outcomes of internationalization. The remaining four themes (entry mode, location choice, internationalization process, and timing) encompass the range of internationalization decisions and actions taken by family firms. Within each IB theme, we evaluate the extent to which scholarly consensus about the influence of family on internationalization exists, highlight theoretical contributions, and identify knowledge gaps and directions for future research. We also explore the host of methodological issues that have limited the development of theory about family firm internationalization and propose solutions. The results of this detailed analysis are presented in the following sections. We begin by discussing family firm definitions and their implications for family firm internationalization research.

FAMILY FIRM DEFINITIONS

Definitions of family firms differ widely across the literatures in family business (Chua, Chrisman, & Sharma, 1999), management (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Schulze, Lubaktin, Dino, & Buchholtz, 2001) and IB (Arregle et al., 2017; Hennart, Majocchi, & Forlani, 2019). Many studies assert that family ownership is the defining proxy (e.g., Carr & Bateman, 2009), whereas others suggest that family firms must have substantial levels of family ownership and involvement in firm management to satisfy the criterion (e.g., Alayo, Maseda, Iturralde, & Arzubiaga, 2019). Other studies differentiate between family-controlled firms (those over which families have unilateral control due to their level of ownership and managerial oversight) and family-influenced firms (over which family owners and managers have much less control) (Chua et al., 1999; Sirmon, Arregle, Hitt, & Webb, 2008). Finally, some researchers contend that emotions, social relationships, and intergenerational succession – that is, the family’s intent to pass ownership of the business to the next generation – are the defining attributes of the family firm that should be integrated into family firm definitions (Salvato, Chirico, Melin, & Seidl, 2019).

The definition of the family firm matters because it identifies characteristics that exert varying influence on internationalization. Characteristics like ownership and managerial involvement are influential, because family firms occupy a distinctive social and institutional position within the economy. The family, along with the Church, State, and educational system, is one of the fundamental social institutions (Calori, Lubatkin, Very, & Veiga, 1997; Whitley, 1992). As such, the family imprints collective knowledge on individuals (Calori et al., 1997; Whitley, 1992) and exerts a mimetic and normative influence on family firm conduct (Arregle, Hitt, & Mari, 2019). Thus, the family imposes a set of institutional constraints upon the family firm and its managers (Arregle et al., 2007). Moreover, historically, family firms have shaped the social, legal, political, and financial institutions that support them (Soleimanof, Rutherford, & Webb, 2018). Institutional forces thus both constrain and enable family firm conduct, and influence different internationalization outcomes. As we will show, differing family firm definitions partially account for inconsistent and conflicting results. Accordingly, we indicate in Appendix 1 the definition of family firms used in each reviewed paper. Table 1 summarizes the main distinguishing characteristics of family firms, and their related meanings and effects on organizations, namely: 1) family influence or control; 2) emotional attachment and identification; 3) distinctive social capital; 4) transgenerational intent; and 5) generational involvement.

LITERATURE REVIEW ON FAMILY FIRM INTERNATIONALIZATION

In this section, we synthetize family firm internationalization studies that address each of seven core IB themes: (1) scale of family firm internationalization (39% of studies); (2) scope of internationalization (8%); (3) entry mode choice (18%); (4) international location choice (3%); (5) internationalization process (16%); (6) pace and rhythm of internationalization (4%); and (7) internationalization performance (12%)6. We summarize core findings and identify conflicts and the sources of inconsistencies across studies in Table 2, and discuss as follows.

Explaining Family Firms’ International Scale

The majority of extant research contends that unique features of family firms influence their international scale. However, there is no consensus about which of these features, alone or in tandem, facilitate or constrain internationalization (Arregle et al., 2017). For example, in a study of international orientation in the world’s top family firms, Carr and Bateman (2009) conclude that family firms are more internationally oriented than non-family firms, whereas Gómez-Mejía, Makri, and Larraza Kintana (2010) reach the opposite conclusion. The effect of owner–management is a particularly contentious issue. For example, stewardship scholars (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, 1997) suggest that family owner–managers’ strong identification with the firm, and their commitment to the long-run welfare of the firm and its employees, motivate them to act in the best interest of the firm, even when presented with challenges and risks. Stewardship thus helps explain the positive influence of family ownership and management on a family firm’s international scale (James, 1999; Singh & Gaur, 2013; Zahra, 2003). In contrast, agency theory scholars (e.g., Santulli, Torchia, Calabrò, & Gallucci, 2019) argue that the many private benefits of owner–management give majority family owners incentive to prioritize control of their firms (Faccio, Lang, & Young, 2001). Because the complexity of international operations often requires that firms delegate authority in ways that reduce control (Alessandri, Cerrato, & Eddleston, 2018), family owners are less likely to internationalize. Van Essen, Carney, Gedajlovic, and Heugens (2015) also conclude that family firms are less internationally oriented, attributing this fact to agency conflicts between majority family shareholders, who are better positioned to reap the private benefits of control, and minority shareholders, who stand to benefit from internationalization and reduced family control. Singla, Veliyath, and George (2014) provide further evidence that these agency conflicts within family firms hinder international scale.

Similar contradictions emerge from studies of family managers’ risk attitude. Gallo and Pont (1996) assume that the alignment of owner–manager interest in family firms reduces agency costs and promotes the firms’ willingness to pursue risky activities such as developing international scale. However, scholars espousing a socio-emotional wealth (SEW) perspective argue that family owner–managers prioritize the preservation of family’s SEW. SEW comprises “the nonfinancial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty” (Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007: 106). Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007) and others (e.g., Chirico, Gómez-Mejia, Hellerstedt, Withers, & Nordqvist, 2020) present evidence suggesting that family-owner managers are so averse to the loss or reduction of SEW that they are willing to forego a certain amount of profit in order to preserve it. However, the effects of this loss aversion on family firm internationalization are not clear. Gómez-Mejía et al. (2010: 224) note that “family firms are pulled in two opposite directions” by SEW, because international diversification lowers both business risk (thus helping preserve SEW) and family control (thus reducing SEW). However, Gómez-Mejía et al.’s empirical results show that, on average, family involvement is associated with lower international scale. Other SEW-based studies reach similar conclusions, both when analyzing internationalization through export (Bannò & Trento, 2016; Dou, Jacoby, Li, Su, & Wu, 2019; Kraus, Mensching, Calabrò, Cheng, & Filser, 2016; Ray, Mondal, & Ramachandran, 2018) and FDI (Baronchelli, Bettinelli, Del Bosco, & Loane, 2016; Carney, van Essen, Gedajlovic, & Heugens, 2015).

The literature suggests that a more nuanced approach to questions concerning the influence of specific attributes on the scale of family firm internationalization may help resolve some of these contradictions. For example, internationalization requires extensive managerial resources (Hitt, Bierman, Uhlenbruck, & Shimizu, 2006), which are frequently lacking in family firms due to their heavy reliance on family leadership and, also, their compensation practices (Neckebrouck, Schulze & Zellweger, 2018). A series of studies document that individual-level characteristics of family managers, such as education and prior international work experience, positively influence international scale (Casillas & Acedo, 2005; Majocchi, D’Angelo, Forlani, & Buck, 2018; Ramón-Llorens, García-Meca, & Duréndez, 2017). Risk aversion and reluctance to reduce family owners’ control of the firm (Fernández & Nieto, 2005; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010; Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino, & Buchholtz, 2001; Sciascia, Mazzola, Astrachan, & Pieper, 2012) also limit the family firm’s access to the financial resources needed for internationalization. Family firms can increase their access to the managerial and financial resources needed to develop their international scale by involving outside (i.e., nonfamily) parties in firm governance (Arregle, Naldi, Nordqvist, & Hitt, 2012), and by raising external capital from minority domestic and foreign shareholders (Dick, Mitter, Feldbauer-Durstmüller, & Pernsteiner, 2017; Majocchi et al., 2018). Outside board members are an important source of experience, knowledge, and professional skills (Calabrò, Mussolino, & Huse, 2009; Purkayastha, Manolova, & Edelman, 2018; Sundaramurthy & Dean, 2008). Their positive influence on international scale is also associated with their impact on board dynamics: the presence of outsiders is associated with reduced principal–principal agency conflict (that is, among family and non-family shareholders; Calabrò, Torchia, Pukall, & Mussolino, 2013; Singla, George, & Veliyath, 2017) and with increased rationality, professional conduct, and more careful consideration of strategic options (Herrera-Echeverri, Geleilate, Gaitan-Riaño, Haar, & Soto-Echeverry, 2016; Majocchi & Strange, 2012). Minority foreign investors are also a valuable source of international market knowledge (Fernández & Nieto, 2006). Hence, both outside directors and nonfamily ownership are positively related to family firms’ international scale.

Scholars agree that family firms’ social capital also influences international scale. However, the nature of social capital’s impact is complex. Generally, a family firm’s organizational social capital is uniquely influenced by the family’s social capital (Arregle et al., 2007), which is characterized by devotion, generosity, solidarity, and close social interactions among family members (Bourdieu, 1994). Such family firm’s social capital lowers monitoring costs, reduces relational risk, and allows family firms to develop effective informal mechanisms (Mustakallio, Autio, & Zahra, 2002) that reduce their cost of governance. It also facilitates knowledge sharing, expands firm-level relational capital (Arregle et al., 2007; Dyer & Singh, 1998; Kano, Ciravegna, & Rattalino, 2021), increases the speed of decision-making (Gallo & Pont, 1996), and facilitates family firm access to international knowledge and host country networks (Basly, 2007; Cheong, Lee, & Lee, 2015). Hence, it positively influences their international scale. However, strong forms of family social capital can also hinder internationalization. Strong family social capital can lead to groupthink (Janis, 1982), amoral familism (the systematic and dysfunctional distrust of outsiders; Banfield, 1958), and strategic hyper-simplicity (the overspecialization on a simple competitive repertoire undermining adaptation and performance; Miller & Chen, 1996). Those factors, when combined with the limited diversity of family managers’ social capital and professional experience, can reduce networking and constrain the firm’s capabilities (Stadler, Mayer, Hautz, & Matzler, 2018) and international scale. It follows that whether or not family firms’ social capital assists in developing international scale depends on specific uses of social networks in each firm, particularly in relation to other types of resources.

Scholars also disagree about which generation of family leadership is more likely to increase international scale (Bannò & Trento, 2016; Dou et al., 2019; van Essen et al., 2015). Claver, Rienda, and Quer (2008) hold that first-generation owners and managers are more risk tolerant and more likely to support internationalization. Others (Cristiano, 2018; Fang, Kotlar, Memili, Chrisman, & De Massis, 2018; Okoroafo & Perryy, 2010) find that succeeding generations of family leaders may be more open to new ideas and growth opportunities and thus contribute to increasing internationalization. We suspect that these divergent results can be explained by addressing specific characteristics of each generations (e.g., levels of education, aspirations, extant international experience), as well as by other heterogeneous characteristics of firms (e.g., family ownership concentration, inheritance rules, minority shareholder protection). These conjectures await rigorous testing.

Hennart et al. (2019) contend that, although family firms on balance tend to be less international, those that focus on high-quality niche products may be well positioned on a global scale. A focus on high-quality niche products helps family firms overcome idiosyncratic internationalization constraints and allows them to leverage their unique capabilities. Hennart et al. (2019) find that family firms pursuing a high-quality global niche business model achieve similar internationalization (exports) as their nonfamily counterparts. Eddleston, Sarathy, and Banalieva (2019) elaborate that such niche strategies work best for professionalized family firms located in countries with a comparatively strong reputation for quality. More generally, the conclusions by Eddleston et al. (2019) point to the moderating role of macro-level formal and informal institutions and firm-level governance practices.

A number of studies confirm that a variety of institutional attributes moderates international scale. With regard to formal institutions, Arregle et al. (2017) argue that greater minority shareholder protection in the home country exacerbates the negative family firm–internationalization relationship. More specifically, greater protection offers minority shareholders an enhanced opportunity to monitor family activity, which harms the relationship between minority shareholders and majority family owners and, consequently, reduces access to resources that family firms need to internationalize. Lehrer and Celo (2017) suggest that national institutional characteristics (i.e., favorable inheritance rules, overall export orientation of the economy, and symbiotic relations between family firms and large internationalized nonfamily firms) help explain the high internationalization level of German family firms.

Among the few studies that investigate the impact of informal institutions, Arregle et al. (2019) suggest that family-level background characteristics, such as family structure, history, and values/traditions, influence international scale. Similarly, soft factors like trust towards other countries (“generalized trust”) (Arregle et al., 2017) and a family-oriented political ideology of government (Duran, Kostova, & van Essen, 2017) are positively related to family firms’ international scale. Studies incorporating macro-level variables generally conclude that family firm internationalization is context-dependent, and that cross-country institutional differences are critical to explaining the relationships between family ownership–management and internationalization.

In sum, existing research has not identified a consistent generalized relationship between family involvement and international scale. Recently, scholars have argued that the search for a general relationship (i.e., whether family firms are indeed more or less internationalized than non-family ones) is an elusive, if not futile, task. For example, Kano and Verbeke (2018) note that the theoretical challenge of establishing a general relationship between family owner–management and internationalization is impossibly complicated by the heterogeneity of family firms. Further, a large-scale meta-analysis by Arregle et al. (2017) found no evidence of a generalized relationship between family owner-management and international scale. Instead, it confirmed that the nature of the relationship (facilitating versus constraining) is determined by a number of firm- and institutional-level idiosyncratic features. As a result, researchers have turned their attention to the effects of specific variables on family firms’ international scale, or to the exploration of complex and non-linear patterns in those relationships (see Almodóvar, Verbeke, & Rodríguez-Ruiz, 2016; Mitter, Duller, Feldbauer-Durstmüller, & Kraus, 2014; Sciascia et al., 2012).

Explaining Family Firms’ International Scope

Unlike broader IB research, most research on international family business does not conceptually or empirically differentiate between international scale and scope. Therefore, the rationales, contingencies, and variables described in the preceding section on ‘international scale’ are, for the most part, assumed to apply to the international scope of the family firm. However, several studies specifically account for international scope, proposing more precise and robust theoretical mechanisms and delivering empirical results that diverge from those summarized earlier. For example, Alessandri, Cerrato, and Eddleston (2018) conclude that family involvement is associated with greater home region orientation, while Arregle et al. (2017) and others (Avrichir, Meneses, & dos Santos, 2016; Bauweraerts & Vandernoot, 2019) specifically associate it with reduced scope of internationalization. In contrast, Zahra (2003) initially speculated, based on stewardship theory, that family involvement should have a positive effect on international scope, but this paper actually found that the effects of ownership and management differ: ownership exerted a positive effect on international scope, and management a negative one. Given that Zahra’s findings challenge key assumptions of the stewardship theory used to develop hypotheses, we address the implications of this study in the assessment section of this article (see also Table 2).

In the main, scholars offer four theoretical arguments to account for lower international scope among family firms. First, Xu, Hitt, and Dai (2020a) argue that increasing international scope creates higher demands on resources, which increases the risk of SEW losses. Second, family leaders are motivated to use their personal business networks to facilitate internationalization, and they tend to prioritize high network trust and high collaboration intensity (Cesinger, Hughes, Mensching, Bouncken, Fredrich, & Kraus, 2016). However, since these personal network ties tend to be limited and regionally bound, international scope tends to be restricted (Jimenez, Majocchi, & Della Piana, 2019; Tsang, 2020) or constrained to a particular region (Banalieva & Eddleston, 2011). Third, increased international diversity requires greater international experience on the part of family members, as well as access to additional capabilities and resources. However, strong family social capital can hinder international scope by limiting the range of available managerial capabilities in a family firm. It can lead to a mismatch between the pool of competencies available in family managers’ social networks and the growing diversity needed for international scope expansion, which reinforces the liability of foreignness for family firms (D’Angelo, Majocchi, & Buck, 2016; Stadler et al., 2018). Finally, strong family social capital helps perpetuate the imprint of the founder on strategy across generations of leadership, which can limit changes in international scope (Suman, 2017).

Other studies explored the impact of outsiders, such as non-family managers, investors, and board members, on international scope. D’Angelo et al. (2016) find that outsiders can provide the bridging and bonding social capital needed to promote international scope, but that these benefits from outsiders are moderated by the level of family influence. In family-influenced firms (that is, those in which the family lacks unilateral control), outsiders have a positive influence on international scope; the positive effects of family governance can combine synergistically with their presence. This positive influence does not hold true in family-controlled firms due to internal family dynamics and, in many cases, conflicting objectives (e.g., dominant family owner–managers strategic choices may be driven by identity-related concerns such as SEW), differing value systems (e.g., the moral order of kinship versus ‘amoral’ motives like shareholder value maximization; Sirmon & Hitt, 2003), and bifurcation bias (defined as a systemic preferential treatment of family assets over nonfamily ones; Kano & Verbeke, 2018).7 Additionally, as aforementioned, a strategic positioning on high-quality niche products can help these family firms to overcome their internationalization constraints (Hennart et al., 2019) and achieve similar international scope as their nonfamily counterparts.

Overall, our review suggests that the international scope of family firms is more constrained than that of nonfamily firms. While the involvement of external actors can alleviate some constraints and positively moderate the international scope of family firms, the level of family involvement and strategic objectives of the family firm are also influential. Studies on family firm international scope show a strong degree of consensus on the effects of various variables related to family owner–management, unlike studies examining other aspects of internationalization.

Explaining Family Firms’ International Entry Modes

A significant number of studies (18% of the reviewed articles) investigate the influence of family ownership and management on international entry mode choice and partner selection. In the main, researchers assume that family firm owners and managers are inherently risk averse and will tend to adopt entry mode strategies that minimize various risks, such as committing too many resources to a single venture (Filatotchev, Strange, Piesse, & Lien, 2007) or dealing with uncertainty (Kao & Kuo, 2017; Kao, Kuo, & Chang, 2013; Kuo, Kao, Chang, & Chiu, 2012). Family firms may also select entry modes that minimize the risk of SEW dissipation (e.g., Monreal-Pérez & Sánchez-Marín, 2017; Scholes, Mustafa, & Chen, 2016). However, different theoretical perspectives suggest that risk aversion may lead to different entry mode preferences.

Studies that approach entry mode choice from a comparative institutional analysis perspective (i.e., transaction cost economics (TCE) and internalization theory) suggest that family firms use cooperative entry modes as a way to address risks associated with low levels of foreign experience (Kuo et al., 2012). Sestu and Majocchi (2020) argue that joint ventures (JV) are more likely when both potential partners are family-owned and managed. A family firm typically own some family-related idiosyncratic assets (such as reputational assets or a long-established network of relationships) that are embedded in the firm and therefore difficult to trade. As such, when assets owned by family firms in different countries are complementary and bundled, a JV is the only efficient governance solution. The decision further depends on the presence of bifurcation bias and on the type of assets deployed in host countries (Kano & Verbeke, 2018; Verbeke & Kano, 2012). Kano and Verbeke argue that when transferring ‘heritage’ assets, i.e., those that hold an emotional/affective meaning for the family, family firms are likely to choose entry modes that maximize control, such as wholly owned subsidiaries (WOS), in order to protect these assets. On the other hand, when transferring ‘commodity’ assets, family firms will seek entry modes that afford the maximum profit potential, regardless of the actual value, contribution, and vulnerability of the assets deployed. Studies using agency theory suggest that high resource commitment entry modes, such as WOS, expose the family firm to problems associated with adverse selection (e.g., supply chain partner quality may be difficult to determine ex ante) and hold-up (e.g., enforcement of contract and other legal issues can make WOS costly to exit). These issues increase agency costs (Filatotchev et al., 2007) and prevent family firms from committing extensive resource bundles in host countries.

SEW-framed studies diverge on the effects of SEW on family firms’ foreign entry mode choices. Some scholars assert that family firms prefer to enter foreign markets through low commitment modes such as export in order to minimize the potential SEW dissipation risk associated with FDI (Monreal-Pérez & Sánchez-Marín, 2017; Scholes et al., 2016). However, WOS afford family firms greater control over operations and therefore may be preferred by family firms that seek to protect SEW (Abdellatif, Amann, & Jaussaud, 2010; Pongelli, Calabrò, & Basco, 2019; Pongelli, Caroli, & Cucculelli, 2016). Pongelli et al. (2016) note, however, that entry preference is likely influenced by family ownership structure, as well as the weight placed by the family on SEW preservation. Scholars have pointed out a family firm paradox in the realm of international JV formation: family firms seem to have a lower willingness to form international JVs, due to the desire to preserve control, even if they have a higher ability to govern them due to their superior relational capabilities (Debellis, De Massis, Petruzzelli, Frattini, & Del Giudice, 2020). Further, the establishment choice for WOS – the choice between a greenfield and an acquisition – has also been investigated, with the majority of studies concluding that family firms prefer greenfield entry to acquisitions, so as to avoid complex acquisition integration processes and maintain full control over the subsidiary, that is, its staffing, organizational design, structure, partnerships, and established routines (Boellis, Mariotti, Minichilli, & Piscitello, 2016; Yamanoi & Asaba, 2018). Boellis et al. (2016) further clarify that the preference is less pronounced in family-owned (rather than family-managed) firms, which are more likely to seek access to external equity to finance the acquisition, and to have professional managers with the requisite integration skills.

The Uppsala model of internationalization (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009; Vahlne & Johanson, 2017) suggests that psychic distance, as well as the liability of outsidership and associated difficulties in penetrating host country networks, shape patterns and modes of international expansion. Kontinen and Ojala (2010), using the Uppsala lens to study family firms’ entry mode choices, argue that family firms exhibit greater cautiousness when entering psychically distant markets by choosing indirect (i.e., non-equity) entry modes. Family firms may subsequently deepen their commitments to foreign markets through FDI. Similarly, Stieg, Cesinger, Apfelthaler, Kraus, and Cheng (2018) observe that, as a family firm’s FDI commitment to foreign markets grows, the firm faces the challenge of shifting its natural emphasis from an internal focus on preserving family harmony to building external networks and resources. This may slow the family firm’s progression toward higher-commitment operating modes in foreign markets.

Entry mode decisions in family firms are multi-dimensional and contingent on, inter alia, the timing of entry, strategic considerations, and macro-level variables. Further, mode choices are dynamic and may evolve through different stages of international expansion. Several recent studies highlight these nuances and contingencies of operating mode dynamics in family firms. For example, Xu, Hitt, and Miller (2020b), introduce decision-making stage as a moderating variable, holding that, in the first stage (entry mode decision), family firms prefer JVs compared to WOS, because the former entail lower financial risks and preserve SEW. In the second stage (i.e., establishment mode decision), the level of family ownership positively influences the likelihood of choosing acquisition as the entry mode; acquiring an ongoing business with access to local networks and markets potentially increases financial returns while reducing threats to SEW. Motivation for foreign expansion also plays a role: family firms that enter foreign markets with a strategic asset seeking motive may show a greater propensity for acquisitions as a way to quickly obtain complementary assets and catch up with international competitors – a strategy that may be more pronounced among family firms in emerging economies (Rienda, Claver, Quer, & Andreu, 2019).

IB research has long established that firm boundaries depend on macro-level characteristics of home and host countries, with institutions playing a critical role in multinational enterprises' (MNEs’) entry mode strategies (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007). Consequently, institutional variables are used to explain the contextual effects moderating the relationships between family firms’ characteristics and their entry mode decisions. Such variables include the home country’s national business systems (i.e., coordinated versus market economies, Geppert, Dörrenbächer, Gammelgaard, & Taplin, 2013), stage of economic development (e.g., family firms from emerging countries especially favor acquisitions when entering developed countries), and the corporate governance practices and rules perceived as legitimate (Luo, Chung, & Sobcza, 2009). Foreign partners whose home country institutional logic more closely resembles family governance principles are probably more open to JVs with family firms.

To summarize, our review suggests that family firms do not exhibit a de facto preference for a particular entry mode. The aggregate analysis of studies addressing family firms’ entry mode choice is consistent with a conceptualization of operating modes proposed by Benito, Petersen, and Welch (2009): Similar to the case of MNEs with dispersed ownership, family firms choose bundles and packages of entry modes based on internal and external contextual factors. These modes are adjusted over time as a function of changing internal and external environments and firms’ evolving experiences. Our view is that many of the conflicting results presented in this section are likely driven by contextual differences among samples. The prospect that other perspectives may lend further insight is addressed later in this article.

Explaining Family Firms’ International Location Choice

Location and entry mode selection are distinct yet interrelated decisions (Benito et al., 2009). As with studies addressing entry mode choice, studies that investigate family firms’ location choice yield mixed findings, partially due to the fact that risk aversion, along with SEW, may lead to different internationalization paths depending on a firm’s strategic objectives. For example, Lien and Filatotchev (2015) observe that high levels of family ownership tend to be associated with higher-risk FDI locations, and attribute this effect to the fact that large block shareholding in family-owned firms facilitates increased monitoring capability and can thus mitigate agency conflicts associated with managerial risk aversion. On the other hand, family firms may favor home regions and culturally similar foreign locations (seen as less risky) in order to protect their equity and their SEW (Baronchelli et al., 2016; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010; Procher, Urbig, & Volkmann, 2013; Strange, Filatotchev, Lien, & Piesse, 2009).

Attention to internal (cognitive) and external (market-based) contextual heterogeneity helps reconcile conflicting results. For example, Boers (2016) posits that psychic distance impacts location choice, but his qualitative study establishes no de facto preference for low psychic distance locations in family firms. Rather, he finds that market choice is strongly influenced by another internal contextual factor – the risk preference of the controlling family. Kano and Verbeke (2018) argue that yet another internal contextual factor, bifurcation bias, influences location choice. They posit that strong bifurcation bias motivates family firms to choose FDI destinations based on a family’s personal preferences, the presence of family networks, and the type of assets invested overseas. The transfer of ‘heritage’ assets will lead bifurcation-biased firms to favor locations that allow ownership of operations by foreign investors. In contrast, unbiased family firms (that is, those that implement routines to safeguard against potential bifurcation bias, and in which internationalization decisions are driven by comparative efficiency considerations) choose foreign markets based on location advantages. In this case, family firms do not display unique location choice patterns.

As such, we conclude from our literature review that no consistent generalized relationship between family ownership/control and location choices has been established. Rather, evidence suggests differences in external contexts and across firms account for diverging decisions in the realm of international location choice.

Explaining Family Firms’ Internationalization Process

The majority of reviewed studies conclude that family firms tend to pursue a traditional, stepwise internationalization model (Graves & Thomas, 2008; Kontinen & Ojala, 2010, 2012), starting with entry through lower-commitment modes, usually in more psychically proximate countries (Claver, Rienda, & Quer, 2008). Patterns of gradual, stepwise expansion are attributed to the challenge of overcoming resource constraints and acquiring the managerial skills, knowledge, and experience needed to compete in international markets (Minetti, Murro, & Zhu, 2015). These constraints make it difficult for family firms to overcome the liability of foreignness in distant markets. Family owners’ risk attitudes also help explain the preference for stepwise internationalization.

However, a number of reviewed papers identify factors that might cause family firms to internationalize rapidly or to pursue nontraditional internationalization patterns. For example, Hennart et al. (2019) note that family firms selling mass-market products that require extensive adaptation in host markets suitably adopt a stepwise internationalization process; nonetheless, family firms pursuing a global high-quality niche strategy can quickly reach high scale and scope of internationalization through export. Kontinen and Ojala (2012) find that, whereas strong stewardship is associated with a stepwise process, weak/moderate stewardship attitudes within the family firm are correlated with so-called ‘born global’ or ‘born-again global’ patterns of internationalization. Meanwhile, Stieg, Hiebl, Kraus, Schüssler, and Sattler’s (2017) study ‘born-again global’ family firms and conclude that succeeding generations of family firm leadership, assuming the requisite education and experience, often re-commit the firm to its original strategic orientation and engage in quick and extensive internationalization. Fernández-Moya (2010) describes early and intense internationalization at the successful Spanish publishing house Salvat; the firm’s quick evolution from a small family business to a large family-owned MNE was supported by capacities for technological and managerial innovation, diverse social networks, and the professionalization of the firm’s management.

More broadly, the international expansion process is thought to follow specific pathways determined by individual, family, organizational, and environmental factors. Individual factors refer to such characteristics of family members as capabilities, stewardship attitudes, and vision and quality of the next generation. At the family level, family aspirations and the degree of family harmony play a role (Graves & Thomas, 2008). Organizational factors include strategic considerations, required resources and capabilities, quality of human capital, openness of governance (Casillas, Moreno, & Acedo, 2010), historical origins of the firm (Huesca-Dorantes, Michailova, & Stringer, 2018), and the nature of relationships within and outside the firm (Cristiano, 2018). Environmental factors encompass various characteristics of the home and host country environment, such as socio-geographic factors, the economic and cultural heritage of home countries, and prevailing cultural values in home and host societies (Shapiro, Gedajlovic, & Erdener, 2003; Verbeke, Yuan, & Kano, 2020).

Intergenerational involvement emerged as a key, but controversial, feature shaping the internationalization process (Graves & Thomas, 2008). Okoroafo (1999) argues that family firms that do not internationalize in the first and second generations are unlikely to do so in later generations. In contrast, Calabrò, Brogi and Torchia (2016) and Cristiano (2018) argue that the involvement of incoming generations positively influences exploration and exploitation of international opportunities, as later generations are more risk tolerant and may be more open to new ideas. However, this effect is contingent on a variety of family attributes, such as the relationships between generations, objectives of the incoming generation, and levels of education and international experience (Stieg et al., 2017).

Several studies focus on specific features of the internationalization process, such as international opportunity recognition. Here, the findings split again. Zaefarian, Eng, and Tasavori (2016) argue that family firms do not proactively initiate international opportunity identification (a conclusion echoed in Ratten & Tajeddini, 2017), but rather learn about cross-border opportunities through accidental discovery, e.g., information acquired through acquaintances and social networks. Marinova and Marinov (2017) arrive at the opposite conclusion, concluding that most family firms in their study proactively sought international clients. Proactive behavior is linked to the family’s international orientation and commitment, as well as to the breadth of its social capital. Similarly, Kontinen and Ojala (2011) observe that firms recognized international opportunities when they established new formal ties but failed to do so when they relied on existing informal or family ties.

Finally, learning is a key determinant of the internationalization process, as illustrated in a rich historical study of large Spanish family firms by Puig and Pérez (2009). The authors find that a firm’s learning process is path-dependent and strongly shaped by major historical events, local and global tensions, and ongoing trends in globalization (see also Castagnoli, 2014). Family firms that internationalized successfully are able to learn managerial lessons from traditional corporations and to adapt to the external environment by diversifying and changing specializations and market niches. Maintaining strong links to local, national and international networks emerged as a critical factor in survival and growth of family firms. These links (often aided by collective action, such as large family lobby groups) facilitated global commercial and political knowledge sharing, fundamental for the development of family capitalism (Harlaftis & Theotokas, 2004; Pérez & Puig, 2009).

We conclude that family firms' international expansion does not follow a particular generalized pattern. Collectively, the studies indicate that internationalization patterns and processes in family firms are idiosyncratic and shaped by history as well as a variety of family, organization, and environment-level variables. Family firm differences across these variables explain the contradicting results discussed above.

Explaining Temporal Aspects Of Family Firms’ Internationalization

Some studies in our sample focused specifically on exploring the pace, rhythm (the regularity of foreign expansion), and timing (early versus later in a firm’s development) of family firm internationalization. While it is often assumed that family firms internationalize slowly and follow a stepwise pattern of international expansion (Graves & Thomas, 2008), studies focusing on temporal dimensions of family firm internationalization suggest that the process is more nuanced. For example, Lin (2012) shows that family ownership increases the pace of internationalization but throws off its rhythm (i.e., internationalization becomes more irregular). Stieg et al. (2017) find that the timing of internationalization is linked to generational successions, but its pace is shaped by successor attributes, such as the successor’s international experience and education level. Kontinen and Ojala (2012) suggest that higher levels of ownership concentration following succession correspond with a greater pace of internationalization. In sum, our review suggests that the temporal patterns of family firm internationalization are contingent on characteristics of the family firm (e.g., ownership concentration, succession, successor attributes), and probably moderated by other dimensions of the internationalization process, including its scale, scope, and stage.

Explaining Family Firms’ Internationalization Performance

Studies that investigate family firm internationalization performance mainly focus on financial outcomes (see Appendix 1). As expected, findings about the effects of family firms’ internationalization on performance are mixed, with some reporting positive (e.g., Stadler, Mayer, Hautz, & Matzler, 2018; van Essen et al., 2015) and others negative effects (Graves & Shan, 2014; Hsu, Kao, & Lee, 2016; Tsao & Lien, 2013). Explanations for these outcomes range from the agency benefits of family governance on financial performance (Hsu et al., 2016) to the constraining effects of family firm’s social networks (Stadler et al., 2018). Seeking to reconcile divergent findings, researchers have turned their attention to international performance contingencies. Mensching, Calabrò, Eggers, and Kraus (2016) show that, the greater the family influence, the more likely the overall perceived success of internationalization; yet these results only apply to host countries with low geographic and cultural distances. Similarly, Banalieva and Eddleston (2011) find that family firms led by family members report higher performance when pursuing a high home region orientation focus, whereas nonfamily leaders generate better performance for family firms expanding outside of the home region. Hernández-Perlines, Moreno-García, and Yañez-Araque (2016) and Hernández-Perlines and Xu (2018) find that international entrepreneurship orientation (IEO) largely explains international performance of family businesses, with innovation the most important dimension of IEO. This IEO–performance relationship is positively mediated by absorptive capacity and by the firm’s environment. Fernández-Moya (2010), Pérez and Puig (2009), and Puig and Pérez (2009) focus on non-financial outcomes of internationalization, such as the evolution of a small family firm into a large family-owned MNE and the successful integration of family-owned firms into the global economy. These papers find that these desirable outcomes are shaped by several factors: managerial skills, capacity for innovation, learning, and ability to adapt to environmental changes. Finally, Lu, Liang, Shan, and Liang (2015) discover that the internationalization of Chinese family firms promotes medium-term growth (i.e., over 3 years) but harms short-term profitability due to firms’ resource constraints and the mistakes they make in the learning process.

More generally, some scholars argue that due to the inherent heterogeneity of firms in general, and family firms in particular, the search for a general relationship between internationalization and financial performance is a conceptual and empirical nonstarter (Hennart, 2007; Verbeke & Brugman, 2009). These scholars advocate a more nuanced approach to studying the performance of family firm internationalization, including a focus on non-financial outcomes. For example, Du, Zeng, and Chang (2018) find that family firm internationalization promotes corporate philanthropy, and that a CEO’s political participation reinforces this effect. Heileman and Pett (2018) show that internationally active family firms are more likely than domestic family firms to pass ownership to the next generation of family members. In linking international performance to family firms’ international strategic objectives and internationalization motives (Verbeke & Brugman, 2009; Verbeke & Forootan, 2012), scholars can improve the quality and precision of family firm internationalization studies.

In conclusion, the study of family firm internationalization outcomes remains one of the most divisive themes in the field. While some scholars attempt to establish a relationship between internationalization levels and financial performance, others, mainly IB scholars, argue that there is no generalized relationship between internationalization and financial performance in family firms. Importantly, non-financial outcomes of internationalization – specifically those related to family firms’ noneconomic goals – remain relatively unexplored.

ASSESSMENT AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

As is already evident from this review, family firm internationalization is highly contested territory, one where scholars have energetically explored theory, tested a variety of questions, and uncovered a breadth of intriguing and yet largely unreconciled findings. The field is thus ripe for further development – and in particular need of theory that may help reconcile earlier findings. To that end, we structured this review around themes that play a central role in the IB literature, which we hope will make this body of work more accessible and relevant to the IB scholar. This review, therefore, differs from extant reviews of this literature because we draw equally on the family internationalization and IB literatures to identify areas that may prove especially fruitful for future research. These include adopting canonical IB theoretical frames when studying family firm internationalization, adopting an original multilevel perspective from IB that allows us to shift the level of analysis from the firm to the individual, family, and macro levels, paying greater attention to temporal perspectives, improving our methodological toolkit, and exploring IB-related phenomena that family scholars have overlooked. These approaches, detailed in the following sections, should help both IB and family business scholars address the inconsistencies in the current literature, and further our knowledge and theory on new IB topics.

International Business Theoretical Approaches And Family Firm Internationalization

As we have seen, a wide breadth of theories has been employed in the study of family firm internationalization. These include general theories like agency theory, RBV, resource dependency theory, social capital, stewardship theory, and TCE, and family business-centric perspectives like SEW and bifurcation bias. Yet, less than 20% of reviewed studies drew on IB theory to inform their analyses.8 Relevant disciplinary theories, including internalization theory, the Uppsala model, the Ownership-Location-Internalization (OLI) paradigm, and international entrepreneurship perspectives, were rarely used as a conceptual lens, and only 36% of the reviewed studies were published in IB journals. The neglect of IB theory is a missed opportunity. IB research has developed rich and eclectic theory that reflects the essence of governing international transactions. We need a more consistent use of a broad, IB-focused theoretical framework in order to accurately explain and predict family firm internationalization and reconcile the mixed findings produced so far.

The notion that firms can create value in cross-border operations by effectively and efficiently matching core firm-specific advantages (FSAs) with the advantages, opportunities, and challenges of foreign locations lies at the heart of IB theory (Verbeke, 2013). To create value this way, firms must overcome the liability of foreignness (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009; Zaheer, 1995), or the added costs created by cultural, institutional, geographic, and economic distance between home and host countries (Ghemawat, 2003a). Classic IB theory studies how firms achieve internationalization objectives in the face of these market imperfections, and links value creation in international markets to a number of core concepts, namely, motivation for internationalization, foreign location choice, entry mode choice, entrepreneurial resource orchestration, knowledge transfer, management of a multinational network, and timing of internationalization (Verbeke, 2013). In other words, a variety of IB theories, including internalization theory, an internationally focused version of TCE, the Uppsala model, the OLI paradigm, the knowledge-based view of the MNE (Kogut & Zander, 1992), evolutionary theory of the MNE (Cantwell, 1989), springboard perspective (Luo & Tung, 2018), and the network view of the MNE (Forsgren, 2017) provide precise analytical lenses for studying the ‘what, where, and how’ (Dunning, 1993; Dunning & Kundu, 1995) of family firm internationalization. Limited integration of IB theories into family firm internationalization research, as found in our review of extant literature, presents barriers for advancing this field of study.

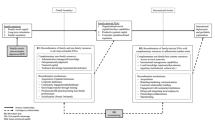

Some have suggested that economic-based IB theory is limited in explaining unique motivations, behaviors, and tensions of internationalizing family firms. Specifically, scholars have argued that IB theory does not account for conflicts within family-based management and ownership groups (Reuber, 2016), does not sufficiently address behavioral aspects relevant for international strategy (Pukall & Calabrò, 2014), and has limited applicability to situations in which non-economic motives drive international strategy (Rugman, 1981). Therefore, we argue that family firm internationalization is best understood at the intersection of IB, family business-centric, and general theoretical perspectives (De Massis et al., 2018). A simplified integrative model of family firm internationalization rooted in IB theory is presented in Figure 1. The framework is inspired by IB research (Benito et al., 2009; Verbeke & Kano, 2016) but also draws upon relevant complementary perspectives identified through our review, in order to paint a comprehensive picture of family firm internationalization.

The starting point of our analysis is the firm’s resource reservoir (Figure 1, Box 1). From the IB perspective, value creation in international markets depends on the firm’s ability to transfer its FSAs to host markets, develop new FSAs in host markets, and recombine extant and new FSAs in novel ways. Thus, whether FSAs are location-bound (LB - nontransferable) and non-location-bound (NLB - transferable) matters. Here, the family firm literature suggests some barriers to FSA development and transfer in family firms may be idiosyncratic; e.g., SEW and bifurcation bias may constrict the transfer of FSAs. Thus, the family business literature highlights how the unique resource endowment of family firms, as well as their idiosyncratic resource gaps and family-influenced strategic logic (Graves & Thomas, 2008), shape their conduct.

Motivations for international expansion and, consequently, FSA transfer (Figure 1, Box 2) are also best understood from a multidisciplinary vantage point. IB theory explains the economic value proposition of foreign expansion – that is, the nature of advantages sought in foreign locations relative to the home country, such as resource-, market-, strategic asset–, and efficiency-based advantages (Dunning, 1993). In family firms, these ‘traditional’ motives for internationalization are often supplemented by family-centric, non-economic motives, such as quality of life issues, dynastic aspirations, reputation enhancement, and the establishment of a family legacy (Berrone, Cruz, & Gómez-Mejía, 2012; Hennart et al., 2019; Kano & Verbeke, 2018).

Concentration of control in family firms (Morck, Wolfenzon, & Yeung, 2005) allows the family to act on its noneconomic preferences, thus influencing the specific international governance decisions and processes presented in Box 3 of Figure 1. Decisions and processes that may differ in family firms include location and entry mode choices, partner selection strategies in cases of cooperative entry, and the use of family social capital to facilitate and safeguard foreign transactions. The rhythm and speed of family firm internationalization also differ because of the temporal orientation of family firms (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005) and issues related to generational succession. Here, IB-specific theoretical approaches such as, inter alia, internalization theory, OLI, the Uppsala model, the network theory, and the springboard perspective, are particularly useful for examining such decisions and processes.

IB theory provides specific tools that allow researchers to accurately link the complexities of internationalization to the idiosyncratic characteristics of family firms. For example, most family business scholars studying family firm internationalization implicitly assume that internationalization is a homogeneous phenomenon involving significant but predictable risks. Yet IB theory clearly shows that international operations can take many forms, each with a different risk profile. For example, and as discussed above, when foreign sales are realized without FDI by exporting (as is the case in many of the samples analyzed in our literature review), family firms can benefit from their unique resource reservoirs to develop a high-quality global niche strategy for exporting with relatively little risk (Hennart et al., 2019).9 IB theory thus provides an important baseline for contextualizing family firm internationalization. Family firm-specific perspectives, in turn, help explain why family firm internationalization behavior may deviate from patterns predicted by efficiency-based IB theory.

IB theory suggests that, over time, competition will eliminate inefficient international governance practices, such as those based on affective or biased decision-making (Verbeke et al., 2020). Yet decision-making in family firms is strongly shaped by affective factors, and/or by the family firms’ unique goals (e.g., those related to SEW preservation). IB theory is uniquely equipped to predict whether international strategy configurations shaped by such factors are likely to result in value creation and growth in international markets, and whether these configurations are sustainable over time. Internationalization outcomes (Figure 1, Box 4) ultimately lead to a feedback loop to the family firm’s resource reservoir (Verbeke & Kano, 2016), whereby the firm’s FSAs are adjusted and augmented based on the firm’s past experience and current operations (Benito et al., 2009; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009). IB thus offers insights into the dynamic process of internationalization and firm growth, as opposed to the more static perspective of family-centric research.

The firm is affected by, and in turn can affect, its macro and micro-level contextual factors through changes in governance (Williamson, 1996), as shown in Box 5 of Figure 1. Institutional theory highlights relevant macro-level features of institutional environments of home and host countries. IB theory extends these insights by examining the multiple effects of distance between home and host countries on international configurations. IB theory traditionally pays less attention to micro (individual-level) variables of family firm international strategies (Kano & Verbeke, 2018), with some exceptions (e.g., behavioral assumptions of bounded rationality and reliability). Here, family business research adds insight by highlighting how variables like family objectives, aspirations, and biases, drive decision-making vis-à-vis internationalization. Moreover, deeper understanding of unique family-level contextual characteristics can be obtained by using complementary perspectives from adjacent theoretical fields, such as anthropology and family science (Arregle et al., 2019).

To summarize, we argue that family firm internationalization is best understood from an IB perspective, infused by insights from the family firm literature as well as general management theory, as outlined in Figure 1. IB theory provides an analytical thread to connect various relevant constructs so as to explain the internationalization process in its entirety. Failure to engage IB theory in family firm internationalization studies is one of the reasons for the field’s fragmentation.

Levels of Analysis in Family Firms’ Internationalization Research: An Imbalanced Literature

IB research has an inherent multilevel structure, one that becomes even more pronounced in studies of family firm internationalization due to the addition of the family as a level of analysis. As a result, we propose four potential levels of analysis (individual, family, firm, and macro) that can influence family firms’ internationalization. Figure 2 visually presents our new framework, which integrates these four levels of analysis with variables considered in existing studies and with variables that we believe future studies should explore (in italics). As detailed below, several key insights can be deduced from Figure 2.

In terms of levels of analysis, the extant family firm internationalization literature is strongly unbalanced, focusing overwhelmingly on the firm level (97% of existing studies). Although some studies include other levels of analysis, such as the individual level (12%), family level (22%), and macro level (20%), cross-level influences remain under-researched. Accordingly, we focus on the individual, family, and macro levels, which present significant potential for future research.

Individual level

As compared to other IB studies, family firm-centric studies tend to place greater focus on behavioral aspects. However, most family firm internationalization studies take for granted individual behavioral aspects that shape decision-making, such as family-centric, affect-based, and/or emotional factors. Indeed, quantitative studies using archival data often assume but rarely measure behavioral characteristics like stewardship, altruism, and risk or loss aversion. Tsang (2006: 999) labels this practice “assumption-omitted testing” and argues that such treatment of behavioral assumptions leads to unconvincing and contradictory empirical results in theory-testing studies. For example, multiple authors report that family involvement in ownership and/or management lessens internationalization due to the family’s desire to avoid SEW dissipation (Bannò & Trento, 2016; Dou et al., 2019; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2010; Ray et al., 2018). Wei and Tsao (2019), in contrast, argue that, due to a family firm’s long-term orientation, many view internationalization as an attractive investment that can generate future value and increase SEW over time (Xu et al., 2020a). Similar contradictions appear in entry mode studies that build on SEW, as discussed above. Yet, as Schulze and Kellermanns (2015: 454) explain, researchers have relied mainly on family ownership and family management (both firm-level constructs) as proxy measures of SEW, the dimensions of which “have remained largely undefined and unmeasured.” In some cases, even firms with the same level of family ownership and management are thought to have different levels of SEW due to differing family preferences, structures, values, and histories. Although SEW is generally viewed as a firm-level construct, its roots reside in family members’ attitudes, cognition, and behaviors. Therefore, the microfoundations of SEW should not be ignored in firm-level studies. This contention is supported by Jiang et al. (2018), who find that most SEW research has overlooked the micro-level mechanisms behind the cause-and-effect relationships of SEW.

Further, even when explicated, micro-level theoretical assumptions lack consistency across studies conducted from different theoretical perspectives. For example, agency, and especially game theoretic, approaches assume full rationality, while TCE assumes bounded rationality. The SEW perspective, in contrast, assumes that affect strongly shapes family firms' conduct, causing them at times to adopt strategies that deviate from 'rational' profit maximization objectives. These divergent behavioral assumptions thus yield conflicting conclusions. However, with some exceptions such as Banalieva and Eddleston (2011) and Holt (2012), the family firm internationalization literature has seen few attempts to reconcile them.

As such, while a rough consensus holds that individuals in family firms can deviate from profit maximization behavior for internationalization and are subject to affective motivations and decision drivers (e.g., SEW, bifurcation bias), no agreement exists on what these motivations are, when they prevail, and how exactly these individual motivations maximize family utility. Consequently, the specific manifestations of relevant actors’ affective preferences in firms’ international strategy, and how they influence existing IB theories’ mechanisms, remain unclear. We argue that the weak theoretical and empirical microfoundations – a weakness also partially recognized in the family business literature (De Massis & Foss, 2018) – prevent scholars from painting a comprehensive picture of family firm internationalization, and, more generally, from leveraging the specificities of family firms to further our knowledge on behavioral components of internationalization. However, this theoretical and empirical gap opens the door to a series of intriguing research questions, including: what kind of parsimonious behavioral assumptions can present a theoretical baseline to explain the behavior of both family and nonfamily actors in family firms? How does this behavior affect internationalization?

Additional theoretical insight is needed to further our understanding about how other factors shape individuals’ decisions about family firms’ internationalization. For example, Xu et al. (2020a) drew on behavioral theory of the firm and found that the role of SEW in family firms’ internationalization scale and scope is shaped by firm performance: when financial performance falls below their aspiration level, family firms are willing to enter more foreign markets (that is, increase scope) despite the potential loss of SEW. Holt (2012) uses image theory to identify conditions under which external actors are able to influence scale and scope of family firm internationalization. Behavioral strategy research thus enriches our understanding of the internationalization behavior of family firms. Cognitive perspectives lend added insight. They suggest that individual decision-makers’ mental models (i.e., an individual’s cognitive structures and processes used to make sense of the world) or small-world representations (i.e., lower dimensional sketches of a situation that an individual believes has the salient characteristics for an appropriate decision) are helpful to delve into the complex mechanisms of internationalization decisions (see Maitland & Sammartino, 2015). We do not know, for example, whether or how the family context shapes family managers’ mental models (e.g., different richness or connectedness) and their internationalization decisions.