Abstract

Ten years ago, Stahl et al. (J Int Bus Stud 41:690–709, 2010) performed a meta-analysis of the literature on cultural diversity and team performance, aiming to improve our understanding of “the mechanisms and contextual conditions under which cultural diversity affects team processes” (p. 691). State-of-the-art studies still echo the article’s conclusion about the ‘double-edged sword’ of cultural diversity, referring to the trade-off between process losses and gains. In this commentary, we assess progress within the past decade on our understanding of this double-edged sword. We argue that in terms of adding new insights, IB, as a field, has made substantial progress with respect to understanding diversity within teams, moderate progress with respect to input-process-output logic, and minimal progress with respect to definitions of cultural diversity. Our recommendations for moving beyond the double-edged sword metaphor in the next decade include shifting focus from cultural diversity per se to how it is managed, moving away from simplicity towards unfolding complexity, and expanding diversity categories beyond culture, and mechanisms beyond knowledge or information.

Résumé

Il y a dix ans, Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt et Jonsen (2010) ont réalisé une méta-analyse de la littérature sur la diversité culturelle et la performance des équipes, visant à améliorer notre compréhension “des mécanismes et des conditions contextuelles dans lesquelles la diversité culturelle affecte les processus d’équipe” (p. 691). Faisant référence au compromis entre les pertes et les gains de processus, des études de référence font toujours écho à la conclusion de l’article sur “l’épée à double tranchant” de la diversité culturelle. Dans ce commentaire, nous évaluons les progrès réalisés au cours de la dernière décennie sur notre compréhension de cette arme à double tranchant. Nous soutenons qu’en termes d’apport de nouvelles idées, l’IB, en tant que domaine, a fait des progrès substantiels en ce qui concerne la compréhension de la diversité au sein des équipes, des progrès modérés en ce qui concerne la logique input-process-output, et des progrès minimes en ce qui concerne les définitions de la diversité culturelle. Nos recommandations pour dépasser la métaphore de l’épée à double tranchant au cours de la prochaine décennie comprennent le déplacement de l’attention de la diversité culturelle en soi vers la façon dont elle est gérée, l’abandon de la simplicité au profit de la complexité, et l’élargissement des catégories de diversité au-delà de la culture, et des mécanismes au-delà de la connaissance ou de l’information.

Resumen

Hace 10 años, Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, y Jonsen (2010) llevaron a cabo un meta-análisis de la literatura sobre diversidad cultural y el desempeño del equipo, buscando mejorar nuestro entendimiento de “los mecanismos y las condiciones contextuales bajo las cuales la diversidad cultural afecta los procesos del equipo” (p- 691). Los estudios de estado de arte siguen haciendo eco a la conclusión del artículo sobre la “espada de doble filo” de la diversidad cultural, refiriéndose a la solución intermedia entre perdidas y ganancias en el proceso. En este comentario, evaluamos el progreso hecho en la última década de nuestro entendimiento de esta espada de doble filo. Sostenemos que, en términos de agregar nuevo conocimiento, negocios internacionales, como campo, ha tenido un progreso sustancial con relación al entendimiento de la diversidad en los equipos, un progreso moderado en relación a la lógica insumo-proceso-resultado, y un progreso mínimo en relación a las definiciones de diversidad cultural. Nuestras recomendaciones para ir más allá de la metáfora de la espada de doble filo en la próxima década incluyen cambiar en enfoque de diversidad cultural per se a cómo es está manejada, alejarse de la simplicidad hacia el despliegue de la complejidad, y expandir las categorías más allá de cultura, y los mecanismos más allá de conocimiento o información.

Resumo

Há dez anos, Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt e Jonsen (2010) realizaram uma meta-análise da literatura sobre diversidade cultural e desempenho de equipe, com o objetivo de melhorar nossa compreensão sobre “os mecanismos e condições contextuais sob os quais a diversidade cultural afeta os processos de equipe” (p. 691). Estudos que representam o estado da arte ainda ecoam a conclusão do artigo sobre a “espada de dois gumes” da diversidade cultural, referindo-se ao trade-off entre perdas e ganhos de processo. Neste comentário, avaliamos o progresso na última década sobre nossa compreensão dessa espada de dois gumes. Argumentamos que, em termos de acréscimo de novos insights, IB, como um campo, fez um progresso substancial no que diz respeito à compreensão da diversidade dentro de equipes, progresso moderado em relação à lógica de entrada-processamento-saída e progresso mínimo em relação às definições de diversidade cultural. Nossas recomendações para ir além da metáfora da espada de dois gumes na próxima década incluem mudar o foco de diversidade cultural per se para como ela é gerenciada, afastando-se da simplicidade na direção da revelação da complexidade e expandindo categorias de diversidade além da cultura e mecanismos além do conhecimento ou informação.

摘要

十年前,Stahl,Maznevski,Voigt和Jonsen(2010)对文化多样性和团队绩效的文献进行了荟萃分析,旨在提高我们对“文化多样性影响团队过程的机制和情境条件”的理解(第691页)。最新的一些研究仍然呼应着该文关于文化多样性的“双刃剑”结论, 指的是过程损失与收益之间的权衡。在这篇评论中, 我们评估过去十年中对这把双刃剑的理解的进展。我们认为, 就增加新见解而言, IB作为一个领域, 在理解团队内部的多样性方面取得了实质性进展, 在输入过程-输出逻辑方面取得了适度的进展, 在文化多样性定义方面取得的进展最小。我们关于在下一个十年里超越双刃剑比喻的建议包括: 将重点从文化多样性本身转移到它如何被管理, 从简单性转变为展现复杂性, 将多样性类别扩展到文化之外, 将机制扩展到知识或信息之外。

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Ten years ago Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, and Jonsen (2010) performed a meta-analysis of the literature on cultural diversity and team performance, aiming to improve our understanding of “the mechanisms and contextual conditions under which cultural diversity affects team processes” (p. 691). A decade of theoretical and empirical work later, cultural diversity still presents a fundamental tradeoff for organizations where employees work within teams (Taras et al., 2019; Tasheva & Hillman, 2019; Tung & Stahl, 2018). As Stahl et al. (2010) summarized it: “cultural diversity in teams can be both an asset and a liability” (p. 705). On one hand, cultural differences between individuals in teams make teamwork more satisfying and make team members better at creative problem solving, but, on the other hand, this collective capability comes at the cost of decreased coordination and efficiency, and increased conflict (Corritore, Goldberg, & Srivastava, 2020). State-of-the-art studies still echo the article’s conclusion about this tradeoff as a ‘double-edged sword’ of cultural diversity (Hajro, Gibson, & Pudelko, 2017; Nederveen Pieterse, van Knippenberg, & van Dierendonck, 2013; Stahl, Miska, Lee, & De Luque Mary, 2017; Zhan, Bendapudi, & Hong, 2015). So, in the past 10 years, where (in what areas) have we advanced in our understanding of this double-edged sword? Where have we not and, most importantly, why?

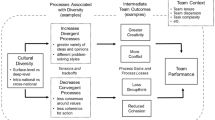

In this commentary, we offer reflections around the key proposition of the 2020 JIBS Decade Award-winning article by Stahl et al. (2010), namely that cultural diversity affects team performance through process losses and gains associated with increased divergence and decreased convergence. Our aim is to further contextualize the agenda outlined in their conclusion in the light of research findings during the past 10 years. Responding to Stahl et al.’s (2010) closing statement, we are pleased to report that there has been substantial progress in repositioning research attention away from cultural diversity per se towards “how the diversity is managed” (p. 705; original italics). Yet, we also argue that this trajectory must continue. That is, in order to “fine-tune our understanding of processes” (p. 705), we need to continue to shift the focus from cultural diversity as a key explanatory variable towards the interaction effect between cultural diversity and contextual influences (referred by Stahl et al. as process-oriented moderator variables).

In what follows, we look back on the citation history of the award-winning article and recollect where it has been studied and how it has changed research conversations. We then zoom in on the key signposts framing a roadmap for future research on the topic of cultural diversity and team performance.

CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN TEAMS: A RADICAL TRAVELING THEORY

According to Web of Science, as of October 2020, the article was cited 344 times in journals and books representing 60 different Web of Science discipline categorizations. Even though Web of Science does not categorize IB separately from other management or business journals, a quick scan shows that a large portion of the management (57%) and business (31%) citations are in IB and IB-related management journals, followed by citations in the fields of applied (16%) and social psychology (5%), and then stretching all the way to single citations in each of the fields of anesthesiology, aerospace engineering, religion, and surgery. In this regard, this article is a good example of the kind of research that can help IB transcend disciplinary borders and move away from being a ‘net importer’ of theories from other disciplines (Yehezkel & Shenkar, 2011).

What makes this article so effective at transcending the disciplinary borders? Or, in the terminology of Oswick, Fleming, and Hanlon (2011), why could Stahl et al. (2010) be considered an example of a radical traveling theory? A radical traveling theory is the kind of theoretical development that is not specifically designed for consumption by a discipline-centric audience; it usually has general theoretical contributions and considerable conceptual latitude. Such a theory should allow a seemingly easy reconceptualization by a ‘foreign’ audience: “a process of repackaging, refining, and repositioning a discourse (or text) that circulates in a particular community for consumption within another community” (p.323). The process of recontextualization allows ‘foreign’ communities of scholars to import the theory and deradicalize it “in order to be more narrowly applied to organizational phenomena and subareas of inquiry” (p.323).

In our opinion, there are two main reasons why a meta-analysis of cultural diversity and team performance appealed to a broad audience beyond IB. Its problematizing attempted to solve an almost-universal challenge, and its implications spawned both new theoretical directions and clear guidance for practice. First, this paper addresses a challenge that is almost mundane in its universality; how cultural diversity affects team processes. In contrast to the equally important current trend towards addressing grand societal challenges (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017), this paper’s popularity is partly due to addressing a challenge that most people can easily relate to their everyday work. Even in academia, researchers in most disciplines and across all levels of analysis have at some point considered how to manage cultural diversity within their research teams, or within their research contexts. Stahl et al.’s meta-analysis demonstrated that many researchers in other disciplines had previously tried to answer similar questions, yet their paper ultimately became more influential than earlier attempts. We suspect this may be partly due to IB’s strength at theorizing the multi-level mechanisms behind team diversity outcomes.

Second, the article achieved similarly strong implications for both theory and practice. In terms of theory, it has become almost obligatory to discuss process losses and gains for any research related to cultural diversity within teams (Hajro et al., 2017; Nederveen Pieterse et al., 2013; Stahl et al., 2017; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007; Zhan et al., 2015). Indeed, this approach is so entrenched that it may be time to consider alternatives, as we discuss in the next section. Surprisingly, Stahl et al.’s (2010) theorizing around convergence and divergence never reached the same level of embeddedness in research at the team level, though research at the other levels, such as IHRM draws on similar arguments (Edwards, Sanchez-Mangas, Jalette, Lavelle, & Minbaeva, 2016; Kaufman, 2016). Perhaps this is because there is a tension, unresolved in Stahl et al. 2010, between similar sets of concepts, such diversity and similarity, convergence and divergence, standardization and differentiation—again, this has been discussed more in IHRM than at the team level (Farndale, Brewster, Ligthart, & Poutsma, 2017; Farndale, Mayrhofer, & Brewster, 2018). As (Molloy & Ployhart, 2012) make clear, construct clarity is key to effective research and, notably, Stahl et al.’s hypotheses on this issue do not use the convergence/divergence terminology.

In terms of practice, managers could also discover concrete changes they could implement from the meta-analytic results. Many of the moderators included in the meta-analysis are easily manageable, such as team size, task complexity, and team tenure. Instead of measuring obscure constructs which offer theoretical elegance but little practical utility, this paper offered both.

WHAT HAVE WE LEARNED ABOUT CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN TEAMS, AND WHAT ARE WE STILL MISSING?

In the decade since this paper was published, the field of IB has made significant progress in understanding how cultural diversity operates within teams. A word cloud visualization of all citations reported by the Web of Science identifies ‘team’ as a keyword, closely followed by ‘culture’, ‘international’, and then ‘leadership’. We further analyzed the citing papers published in JIBS and other level 4 and 4* AJG journals in Nvivo (in total 79 papers). We searched the citing papers for references to Stahl et al. (2010) and coded the identified references using the key concepts of the Stahl et al.’s original paper (e.g., ‘creativity’, ‘communication effectiveness’, ‘social integration’) as well as inductively generated codes (e.g., ‘input-process-output logic’, ‘positivism’, ‘co-located vs. virtual teams’). We also looked through the abstracts of the remaining citing papers published in other academic, peer-reviewed outlets to double check for the findings relevant for IB. Based on our analysis, we argue that in terms of the adding new insights, IB, as a field, has made substantial progress with respect to understanding diversity within teams, moderate progress with respect to input-process-output logic, and minimal progress with respect to definitions of cultural diversity (see Table 1).

Diversity within Teams

The past decade has seen a boom in research about diversity effects within teams, mostly framing it as a pursuit of the benefits of the double-edged sword while suppressing the drawbacks. Among the 79 citing articles that we analyzed in Nvivo, the double-edged sword was identified as a key concept in 26 papers. Stahl et al.’s award-winning paper has benefitted the field by pushing researchers to consider both positive and negative effects from cultural diversity within teams. For example, diverse teams clearly stimulate creativity and innovation (Backmann, Kanitz, Tian, Hoffmann, & Hoegl, 2020; Jang, 2017), paralleling similar findings related to multiculturalism at the individual level (Tadmor, Galinsky, & Maddux, 2012; Vora, Martin, Fitzsimmons, Pekerti, Lakshman, & Raheem, 2019). Further afield, the X-Culture project’s rich data have spawned a new research community interested in global virtual teams that commonly takes the same double-edged sword approach (Jimenez, Boehe, Taras, & Caprar, 2017; Taras et al., 2019). For example, within global virtual teams, diversity stemming from personal factors like age, gender, and language skills had a negative effect on team performance, while diversity stemming from contextual factors like economic development, human development, income inequality, or corruption had a more positive effect on team performance (Taras et al., 2019). The negative effect of personal diversity was stronger for psychological outcomes, while the positive effect of contextual diversity was stronger for task outcomes. Some research veers away from the double-edged sword framing by focusing entirely on the positive benefits of diverse teams, including research by the original article’s first author (Stahl et al., 2017; Stahl & Tung, 2015). Overall, the double-edged sword approach to examining cultural diversity within teams has built a strong body of evidence that team diversity generally supports creativity, problem-solving and knowledge generation, but can impede communication and efficiency (Zhan et al., 2015). Indeed, claims like the team diversity–creativity link are so well substantiated by now that it may be time to lay them to rest, turning our attention to relationships that are less well understood.

Research on the process losses that often occur in diverse teams tends to distinguish between different types of diversity (Zhan et al., 2015), such as Stahl et al.’s (2010) distinction between surface-level and deep-level diversity. However, the distinction between surface- and deep-level differences may unintentionally dismiss meaningful differences between people related to categories such as language, ethnicity, age, and gender, and as if they were less important than others like culture. We suspect it is not researchers’ intention to rank differences in terms of their importance relative to one another, but the surface- vs.-deep distinction implies a ranking nonetheless. For example, research about language differences within teams has been often considered a surface-level difference and found process losses due to communication challenges (Hinds, Neeley, & Cramton, 2014; Tenzer & Pudelko, 2015; Tenzer, Pudelko, & Harzing, 2014). As discussed ahead in the section on definitions of cultural diversity, we admire the stream of research on language differences in diverse teams for their expanded repertoire of mechanisms, including emotions, power dynamics, and identity, relative to most research that uses information and knowledge flows as the primary mechanism. Thus, treating linguistic differences as though they exist only at the surface level downplays their importance. Overall, we suggest that it may be time to retire the distinction between surface- and deep-level differences.

One trend that emerged in the later part of the decade was, as Stahl et al. advocated in 2010, a focus on the intra-team processes through which team diversity can be leveraged to attract more process gains and limit process losses. For example, a study published exactly one decade later explains how multicultural individuals bridge gaps among their multinational team members (Backmann et al., 2020). An earlier study explained how a similar mechanism of cultural brokering promoted creativity within diverse teams by eliciting or integrating knowledge from diverse team members (Jang, 2017). Other studies have discovered that knowledge exchange processes are a key link through which the organizational diversity climate influences the effectiveness of multicultural teams (Hajro et al., 2017).

Ultimately, researchers in the past decade have unpacked many of the processes hinted at in Stahl et al.’s meta-analysis. Where a meta-analysis’ strength is discovering overall patterns among broad categories of constructs, researchers have spent the time since the original article was published examining those team processes in detail to see what they entail. We now think it may be time to return to the bigger picture, systematizing different approaches to examining cultural diversity within teams under a broader framework, supporting its utility for both theorizing overall relationships, and for practicing managers looking for evidence-backed suggestions about how to manage diverse teams.

Moreover, we suspect the double-edged sword concept may be holding back further progress in terms of both discovering new ways to define culture and building better insights about how to manage diversity within teams. It is limiting by placing the emphasis on cultural diversity as antecedent. That is, in contrast to Stahl et al.’s (2010) request that future researchers focus on how diversity is managed, most double-edged sword projects examine the dual outcomes of diversity itself.

Input-Process-Output

This approach has made progress along the same lines as just described for diversity within teams, especially related to discovering how constructs mediate and moderate the team diversity–performance relationship. For example, we know more about how diversity climates (Hajro et al., 2017) and diversity mindsets (Nederveen Pieterse et al., 2013; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007) moderate the team diversity–performance relationship, such that relationships tend to be stronger when the organizational context or individual mindsets accurately recognize and espouse the benefits of diversity. As described above, diverse teams also benefit through the mediator of individuals brokering or bridging across cultures, languages, and global distance virtually (Backmann et al., 2020; Jang, 2017; Jimenez et al., 2017; Taras et al., 2019).

Despite this progress, many researchers have referenced Stahl et al. (2010) to superficially describe the general logic of how and why cultural diversity matters for performance. For example, many papers cite Stahl et al. (2010) to justify a general claim that diverse teams benefit from different sources of knowledge or ways of operating within a team, including mostly static examinations of how diverse teams transform their diversity into outputs like performance. Recently, Einola and Alvesson (2019) criticized this approach: “much of this literature is either focused on investigating static structural aspects and contextual characteristics of teams leading to different outcomes, or on input–process–output models” (p. 1892). They distinguish input-process-output models from more authentically processual models in that in the latter teaming processes unfolds over time, even when teams start with similar inputs. One strong example of a processual model is Cramton and Hinds’ (2014) dynamic systems approach that found diverse teams’ adaptation processes over time cannot be contained within the teams themselves. Instead, they are embedded in the local contexts of team members and influenced by tensions between team member contexts (Cramton & Hinds, 2014). Thus, although there has been moderate progress in terms of understanding mediating and moderating variables that explain the relationship between team diversity and team performance, we anticipate the next step will be to examine the role of time in diverse teams, as described in the following sections.

Definitions of Cultural Diversity

Finally, it surprised us to discover that so many researchers cite Stahl et al. (2010) with respect to defining cultural diversity at the team level. Indeed, our NVivo analysis showed that referencing Stahl et al.’s paper became a standard when the citing papers want to talk about team-level diversity, with 11 out of the 79 papers we analyzed using it in this manner. Yet, our claim that this area has made minimal progress is not necessarily a problem, as Stahl et al.’s (2010) paper came at the end of a long period of creativity in finding ways to define culture (Chao & Moon, 2005; Hong, Morris, Chiu, & Benet-Martínez, 2000; Leung, Bhagat, Buchan, Erez, & Gibson, 2005; Shenkar, Luo, & Yeheskel, 2008). New ways to define culture have been developed within the past decade, as in a mid-decade JIBS special issue on conceptualizing culture (Caprar, Devinney, Kirkman, & Caligiuri, 2015), and the idea that multiculturalism can be an intra-personal construct (Vora et al., 2019). The concept of cultural diversity within teams has become more dynamic, more embedded contextually, less reliant on cultural values as the primary explanatory variable, and more sensitive to levels issues during this decade.

Despite these examples of progress, our Nvivo analysis of papers citing Stahl et al. (2010) to justify definitions of team diversity found several patterns that may be holding back progress in building better definitions. First, most often the references were made to national diversity, and occasionally (but thankfully not often) it is still being treated as a substitute for culture. References were less often made to diversity stemming from ethnicity or race, and almost never to religion. Next, citing papers commonly drew on the conceptual distinction between surface-level and deep-level diversity (Eagly & Chin, 2010; Taras et al., 2019; van Vianen, de Pater, Kristof-Brown, & Johnson, 2004; Wang, Cheng, Chen, & Leung, 2019), which we critiqued in the earlier section on diversity within teams.

Finally, citing papers could be better at distinguishing between types of diversity – separation, variety or disparity (Harrison & Klein, 2007). Not only do researchers rarely specify which type of diversity they assess, but the measurement of team diversity is sometimes a poor fit for its conceptualization. As Harrison and Klein (2007) argued, “failure to recognize the meaning, maximum shape, and assumptions underlying each type has held back theory development and yielded ambiguous research conclusions” (p. 1199). As we argue in the next section, expanding diversity categories beyond culture will require (a) careful conceptualization of what we mean by diversity as diversity is “not one thing but three things” (separation, variety, or disparity) and (b) correct matching of “a specific operationalization of diversity to a specific conceptualization of diversity” (Harrison & Klein, 2007:1200). Further, framing diversity as informational or knowledge variety naturally lends itself to theorizing on the basis of information and knowledge sharing within teams (Hajro et al., 2017; Klitmøller & Lauring, 2013; Ravlin, Ward, & Thomas, 2014). This tendency was so strong as to overwhelm alternative mechanisms such as power dynamics, emotions, or social networks. Thus, the team cultural diversity literature is not especially diverse in either its conceptualization of diversity or its most common theoretical mechanisms. Even though the past decade has seen new and emerging definitions of what it means to have a diverse team, this remains one of the areas where we see the most opportunity for progress.

Overall, we attribute both the last decade’s impressive progress and its blind spots to the contextual constraints within the field of international business. That is, as a field, our traditional focus on cross-cultural interactions has allowed us to develop innovative and important models to explain how diversity operates within teams. Yet, this same focus has simultaneously held us back from considering the broader environment of diversity within teams.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE?

We suggest a multipronged approach to advancing our understanding of diversity within teams. Each suggestion resolves issues we identified under one of the topics already described:

-

1.

From cultural diversity per se to how the diversity is managed

-

2.

Away from simplifying towards unfolding complexity

-

3.

Expand diversity categories beyond culture, and mechanisms beyond knowledge

From Cultural Diversity Per Se to How Diversity Is Managed

This suggestion is designed to continue the progress made during the past decade within the general topic of diversity within teams, as already described. One of the authors of this piece works with an MNE that has a commonly accepted narrative around the role of diverse work teams. Managers at this firm commonly espouse the notion that diversity is their reality, but inclusion is their managerial choice. Further, they say that diversity is what they have as a basic work condition, but their choices when working with diverse teams represent who they are as a company. This company – like many other multinationals – long ago realized that cultural diversity per se is not necessarily a strategic resource unless it is mobilized and deployed in such a way that differentiates the firm from its competitors.

In the language of the strategic human capital literature, human capital is composed of individuals’ KSAOs (knowledge, skills, abilities and other characteristics; where other characteristics can include individuals’ cultures). When individuals with their cultural differences are combined into culturally diverse teams, a unit-level human capital resource emerges. Yet, the unit-level human capital resource does not always contribute to the pursuit of the unit-relevant economic purpose (Nyberg et al., 2014; Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011). Ployhart, Nyberg, Reilly, and Maltarich (2014) provide an illustrative example:

[A] person’s skill in speaking Farsi as a second language would constitute a human capital resource for a specific unit that operates where translations to or from that language are relevant for the unit’s performance. In contrast, if the same person worked for a different unit in which the ability to speak Farsi was not relevant to that unit’s performance, the … skill would not be a human capital resource for that unit (pp. 377–378).

The Ployhart et al. (2014) framework further distinguishes between human capital resources and strategic human capital resources. While both unit-level capacities are based on individual KSAOs, their functions differ. The former supports unit performance, while the latter supports competitive advantage (Ployhart et al., 2014).

Building on these distinctions, we argue that the interactions between cultural diversity and firm attributes are likely a primary explanation for how team cultural diversity can become a strategic human capital resource, i.e., valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (Barney, 1991). With Ployhart and Chen (2019), we argue that questions like “does diversity matter?” are perhaps theoretically interesting, but “they distract from the far more important practical questions of how, when, and why meso-level [team] processes transform individual-level human capital towards positive contributions to firm outcomes” (p. 363). Shifting research attention will contribute to moving beyond the double-edged sword dilemma (Hajro et al., 2017; Nederveen Pieterse et al., 2013; Stahl et al., 2017; Taras et al., 2019; Zhan et al., 2015) to developing more direct implications for practice.

Towards this goal, we encourage researchers to explore a broad spectrum of possible interactions between team cultural diversity and attributes of the immediate organizational context. These interactions may either create or reduce positive complementarities. For example, there is some evidence that leadership style, strategies, and modes may create positive synergies with team cultural diversity, and that these synergies in turn create emergence-enabling contexts (Zander & Kogut, 1995). Future research could explore many more possibilities for creating culturally diverse teams with positive synergies that would amplify “behavioral processes, cognitive mechanisms, and affective psychological states” (Ployhart & Moliterno, 2011: 135). The interaction between cultural diversity and these attributes will generate interfirm heterogeneity, firm specificity, social complexity, path dependence, and causal ambiguity.

Another mechanism that was identified in Stahl et al.’s original paper as a potential moderator is the task environment. More specifically, the authors focused on task complexity, but the results were inconclusive (Leung & Wang, 2015). One way forward would be to enrich the understanding of task complexity by following Ployhart and Moliterno’s (2011) suggestion to conceptualize the complexity of a unit’s internal task environment as “consisting of four dimension: temporal placing, dynamism of the task environment, strength of member linkages, and workflow structure” (p. 135). Some of the four dimensions will create positive synergies (e.g., strength of member linkages), others may be negative (e.g., temporal placing), and there may also be non-linear effects (e.g., dynamism of the task environment).

Notably, there may be sets of organizational attributes that interact with team cultural diversity to produce positive synergies, qualitatively distinct from those that reduce complementarities. For example, cultural diversity in the context of highly people-oriented leadership (Zander, Mockaitis, & Butler, 2012) will likely create positive synergies. Yet, a context with low levels of people-oriented leadership will not produce the opposite effect. Future research should carefully identify, unfold, and examine the theoretical logic underpinning the possible interactions of cultural diversity with organizational attributes.

Away from Simplifying towards Unfolding Complexity

One strength of the Stahl et al. (2010) paper is that despite its clear focus on culture in teams, it didn’t try to oversimplify its arguments. Arguably, all theories are based on simplified assumptions (Bettis, Gambardella, Helfat, & Mitchell, 2014). But, as Tsoukas (2017) argues, simplification comes “with a heavy price: they [simplified theories] miss the ‘understanding backwards –living forward’ dialectic that critically permeates the lives of those management scholars” (p. 134). He further explains:

Life is understood ‘backwards’ when detached theorists abstract and simplify what practitioners were experiencing while they were living it ‘forward’. No surprise, then, that practitioners often complain that management theories are not related to the real world.

We argue that to move away from simplification in the research on cultural diversity will require contextualizing its object of study (i.e., team) and bringing the element of time back into research logics. Research that followed the Stahl et al. (2010) article developed the importance of the context in which teams and their members operate. As already described in our proposal to focus on how diversity is managed, there is plenty of space for further research on contextual interactions with diversity on team performance. We need to move beyond simplifying context towards unfolding complexity. In particular, we need complex theories of cultural systems emphasizing interactions and accompanying feedback loops that constantly change the systems; the context needs to be part of what is being researched. For example, health care teams with poor physical work environments and high work demands were more likely to gain innovation from team reflexivity than those with better physical work environments, or lower work demands (Schippers, West, & Dawson, 2015), illustrating a contextual boundary condition around the process of team reflexivity.

Time is a final issue we would like to see included more explicitly in future research (van Knippenberg & Mell, 2016). The development of multicultural teams over time and the differing advantages and disadvantages that they had at various time points was identified in the 2010 article, and time of course will apply at all the levels that Stahl et al. (2010) explored. Individuals change over time and with experiences. Even if the same individual is involved at various stages of the team’s processes, they may not ‘be the same person’. Few teams remain the same over long periods of time and the differences between those that do and those that do not, the impact of each replacement, and the associated changes in process are all areas for further research. Similarly, the context will change: a team established, operating, and closing before the COVID-19 pandemic will be different from a team established and operating during the pandemic and they will be different from the teams that will eventually – we hope – be established and operate after the pandemic has been controlled.

Expand Diversity Categories beyond Culture, and Mechanisms beyond Knowledge

Earlier, we expressed concerns about the surprising lack of diversity about team cultural diversity literature, at least within the field of IB (Jonsen, Maznevski, & Schneider, 2011). We noticed a concentration of (especially empirical) studies that conceptualize cultural diversity in terms of its informational variety, where individuals each share different knowledge with one another. Worse, some that rely on this conceptualization do not necessarily measure it as a variety variable (Harrison & Klein, 2007). As we explained above, the obvious solution is for researchers to specify whether their diversity effects are driven by variety, separation, or disparity, and to match measures to the conceptualization they specify (Harrison & Klein, 2007). Yet, this seemingly simple recommendation could have far-reaching effects, if diversifying away from informational variety as the dominant form of diversity facilitates research into alternative theoretical mechanisms and an expanded set of diversity categories.

For example, Ren, Gray, and Harrison (2015) conceptualized team diversity in terms of attitude separation, status disparity, and information variety. These three different approaches to conceptualizing team diversity facilitated a novel research direction by mapping social network composition associated with each form of diversity. Clear specification of the forms of diversity might also help researchers explore alternatives to the surface- vs. deep-level diversity dichotomy. That is, despite the problematic ranking implied by the terms surface- vs. deep-level diversity, researchers have consistently found worse team-level outcomes when measuring demographic diversity like age, gender, and ethnicity, compared to generally more positive outcomes when measuring traditional cultural characteristics like values, attitudes, and norms (Jonsen et al., 2011; Taras et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Although we argued in the ‘diversity within teams’ section that it may be time to retire the terms referring to surface- vs. deep-level diversity, we do not advocate for ignoring related findings. Instead, alternative explanations could be related to factors such as the degree of separation between groups, or the disparity between token team group members versus others. In this way, mechanisms that are under-utilized in IB’s treatment of diversity could supplement the currently dominant explanatory mechanisms of information and knowledge sharing. We would particularly like to see more team diversity research that examines mechanisms popular in diversity research outside of IB, including power differentials, status, stigma, emotions or networks (Nkomo, Bell, Roberts, Joshi, & Thatcher, 2019).

Related to this call for a broader range of mechanisms, we propose a simple solution to our earlier complaint that team diversity research in JIBS and other IB journals continues to be dominated by societal and sometimes national cultures. It is time for IB team diversity research to expand the range of diversity categories considered. This expanded set could include traditional categories usually studied by diversity and inclusion researchers, such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, physical abilities, and sexuality (Nkomo et al., 2019; van Knippenberg & Mell, 2016). It could also include categories like social class or educational training, as proposed by Jonsen et al. (2011) in a follow-up after their award-winning paper. This may have implications for methodology, where ethnography, diary studies, or participant observation, may be appropriate. If IB researchers can improve the ways we specify and measure the diversity construct and expand the set of explanatory mechanisms and diversity categories we consider, we could do something similar to Stahl et al. (2010). That is, we could use our field’s expertise in understanding cross-cultural dynamics to build another ‘radical traveling theory’ about diverse teams.

CONCLUSION

The Stahl et al. (2010) article has had an exemplary influence on research since its publication. This is because of the strength of the work and the thinking involved as well as the felicitous and memorable way in which the thoughts were expressed. One decade after its initial publication, diversity within teams remains a challenging and important organizational phenomenon. Moreover, the field has moved forward in how it examines team diversity, partly due to Stahl et al. (2010) push to go beyond the extant research and to explore further areas that may have an impact. We are looking forward to seeing what cultural diversity models will be developed over the next decade, ultimately bringing more dynamic, more active, and more contextualized understandings of how diversity operates within teams.

REFERENCES

Backmann, J., Kanitz, R., Tian, A. W., Hoffmann, P., & Hoegl, M. (2020). Cultural gap bridging in multinational teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(8), 1283–1311.

Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1): 99–120.

Bettis, R., Gambardella, A., Helfat, C., & Mitchell, W. (2014). Quantitative empirical analysis in strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 35(7), 949–953.

Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. 2017. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1045–1064.

Caprar, D. V., Devinney, T. M., Kirkman, B. L., & Caligiuri, P. 2015. Conceptualizing and measuring culture in international business and management: From challenges to potential solutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 46: 1011–1027.

Chao, G. T., & Moon, H. 2005. The cultural mosaic: A metatheory for understanding the complexity of culture. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90: 1128–1140.

Corritore, M., Goldberg, A., & Srivastava, S. B. 2020. Duality in diversity: How intrapersonal and interpersonal cultural heterogeneity relate to firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(2): 359–394.

Cramton, C. D., & Hinds, P. J. 2014. An embedded model of cultural adaptation in global teams. Organization Science, 25: 1056–1081.

Eagly, A. H., & Chin, J. L. 2010. Are memberships in race, ethnicity, and gender categories merely surface characteristics? American Psychologist, 65(9): 934–935.

Edwards, T., Sanchez-Mangas, R., Jalette, P., Lavelle, J., & Minbaeva, D. 2016. Global standardization or national differentiation of HRM practices in multinational companies? A comparison of multinationals in five countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(8): 997–1021.

Einola, K., & Alvesson, M. 2019. The making and unmaking of teams. Human Relations, 72(12): 1891–1919.

Farndale, E., Brewster, C., Ligthart, P., & Poutsma, E. 2017. The effects of market economy type and foreign MNE subsidiaries on the convergence and divergence of HRM. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1065–1086.

Farndale, E., Mayrhofer, M., & Brewster, C. 2018. The meaning and value of comparative human resource management: An introduction. In C. Brewster, M. Mayrhofer, & E. Farndale (Eds), Handbook of research on comparative human resource management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hajro, A., Gibson, C. B., & Pudelko, M. 2017. Knowledge exchange processes in multicultural teams: Linking organizational diversity climates to teams’ effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1): 345–372.

Harrison, D. A., & Klein, K. J. 2007. What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(4): 1199–1228.

Hinds, P. J., Neeley, T. B., & Cramton, C. D. 2014. Language as a lightning rod: Power contests, emotion regulation, and subgroup dynamics in global teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(5): 536.

Hong, Y.-Y., Morris, M. W., Chiu, C.-Y., & Benet-Martínez, V. 2000. Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologist, 55(7): 709–720.

Jang, S. 2017. Cultural brokerage and creative performance in multicultural teams. Organization Science, 28(6): 993–1009.

Jimenez, A., Boehe, D. M., Taras, V., & Caprar, D. V. 2017. Working across boundaries: Current and future perspectives on global virtual teams. Journal of International Management, 23(4): 341–349.

Jonsen, K., Maznevski, M. L., & Schneider, S. C. 2011. Diversity and its not so diverse literature: An international perspective. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 11: 35–62.

Kaufman, B. E. 2016. Globalization and convergence–divergence of HRM across nations: New measures, explanatory theory, and non-standard predictions from bringing in economics. Human Resource Management Review, 26(4): 338–351.

Klitmøller, A., & Lauring, J. 2013. When global virtual teams share knowledge: Media richness, cultural difference and language commonality. Journal of world Business, 48(3): 398–406.

Leung, K., Bhagat, R. S., Buchan, N. R., Erez, M., & Gibson, C. B. 2005. Culture and international business: Recent advances and their implications for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 36: 357–378.

Leung, K., & Wang, J. 2015. Social processes and team creativity in multicultural teams: A socio-technical framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(7): 1008–1025.

Molloy, J., & Ployhart, R. 2012. Construct clarity: Multidisciplinary considerations and an illustration using human capital. Human Resource Management Review, 22(2): 152–156.

Nederveen Pieterse, A., van Knippenberg, D., & van Dierendonck, D. 2013. Cultural diversity and team performance: The role of team member goal orientation. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3): 782–804.

Nkomo, S. M., Bell, M. P., Roberts, L. M., Joshi, A., & Thatcher, S. M. 2019. Diversity at a critical juncture: New theories for a complex phenomenon. Academy of Management Review, 44(3): 498–517.

Nyberg, A. J., Moliterno, T. P., Hale, D., & Lepak, D. P. (2014). Resource-based perspectives on unit-level human capital: A review and integration. Journal of Management, 40, 316–346.

Oswick, C., Fleming, P., & Hanlon, G. 2011. From borrowing to blending: Rethinking the processes of organizational theory building. Academy of Management Review, 36(2): 318–337.

Ployhart, R. E., & Chen, G. 2019. The vital role of teams in the mobilization of strategic human capital resources. Handbook of research on strategic human capital resources. London: Edward Elgar.

Ployhart, R. E., & Moliterno, T. P. (2011). Emergence of the human capital resource: A multilevel model. Academy of Management Review, 36, 127–150.

Ployhart, R. E., Nyberg, A. J., Reilly, G., & Maltarich, M. A. 2014. Human capital is dead; long live human capital resources! Journal of Management, 40(2): 371–398.

Ravlin, E. C., Ward, A.-K., & Thomas, D. C. 2014. Exchanging social information across cultural boundaries. Journal of Management, 40(5): 1437–1465.

Ren, H., Gray, B., & Harrison, D. A. 2015. Triggering faultline effects in teams: The importance of bridging friendship ties and breaching animosity ties. Organization Science, 26(2): 390–404.

Schippers, M. C., West, M. A., & Dawson, J. F. 2015. Team reflexivity and innovation: The moderating role of team context. Journal of Management, 41(3): 769–788.

Shenkar, O., Luo, Y., & Yeheskel, O. 2008. From ‘Distance’ to ‘Friction’: Substituting metaphors and redirecting intercultural research. Academy of Management Review, 33: 905–923.

Stahl, G. K., Maznevski, M. L., Voigt, A., & Jonsen, K. 2010. Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 690–709.

Stahl, G. K., Miska, C., Lee, H.-J., & De Luque Mary, S. 2017. The upside of cultural differences: Towards a more balanced treatment of culture in cross-cultural management research. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(1): 2–12.

Stahl, G. K., & Tung, R. 2015. Towards a more balanced treatment of culture in international business studies: The need for positive cross-cultural scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 46: 391–414.

Tadmor, C. T., Galinsky, A. D., & Maddux, W. W. 2012. Getting the most out of living abroad: Biculturalism and integrative complexity as key drivers of creative and professional success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(3): 520–542.

Taras, V., Baack, D., Caprar, D., Dow, D., Froese, F., Jimenez, A., et al. 2019. Diverse effects of diversity: Disaggregating effects of diversity in global virtual teams. Journal of International Management, 25(4): 100689.

Tasheva, S. N., & Hillman, A. 2019. Integrating diversity at different levels: Multi-level human capital, social capital, and demographic diversity and their implications for team effectiveness. Academy of Management Review, 44(4): 746–765.

Tenzer, H., & Pudelko, M. 2015. Leading across language barriers: Managing language-induced emotions in multinational teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(4): 606–625.

Tenzer, H., Pudelko, M., & Harzing, A.-W. 2014. The impact of language barriers on trust formation in multinational teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(5): 508–535.

Tsoukas, H. 2017. Don’t simplify, complexify: From disjunctive to conjunctive theorizing in organization and management studies. Journal of Management Studies, 54(2): 132–153.

Tung, R. L., & Stahl, G. K. 2018. The tortuous evolution of the role of culture in IB research: What we know, what we don’t know, and where we are headed. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(9): 1167–1189.

van Knippenberg, D., & Mell, J. N. 2016. Past, present, and potential future of team diversity research: From compositional diversity to emergent diversity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 136: 135–145.

van Knippenberg, D., & Schippers, M. D. 2007. Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58: 515–541.

van Vianen, A. E. M., de Pater, I. E., Kristof-Brown, A. L., & Johnson, E. C. 2004. Fitting in: Surface- and deep-level cultural differences and expatriates’ adjustment. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5): 697–709.

Vora, D., Martin, L., Fitzsimmons, S. R., Pekerti, A., Lakshman, C., & Raheem, S. 2019. Multiculturalism within individuals: A review, critique, and agenda for future research. Journal of International Business Studies, 50: 499–524.

Wang, J., Cheng, G. H. L., Chen, T., & Leung, K. 2019. Team creativity/innovation in culturally diverse teams: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(6): 693–708.

Yehezkel, O., & Shenkar, O. 2011. Knowledge flows in international business: A JIBS citation analysis. In S. Mariano, M. Mohamed, & Q. Mohiuddin (Eds), The role of expatriates in MNCs knowledge mobilization: 45–62. London: Emerald.

Zander, U., & Kogut, B. 1995. Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of organizational capabilities: An empirical test. Organization Science, 6: 76–92.

Zander, L., Mockaitis, A. I., & Butler, C. L. 2012. Leading global teams. Journal of World Business, 47(4): 592–603.

Zhan, S., Bendapudi, N., & Hong, Y. Y. 2015. Re-examining diversity as a double-edged sword for innovation process. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(7): 1026–1049.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Alain Verbeke, Editor-in-Chief, 22 October 2020. This article has been with the authors for one revision and was single-blind reviewed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Minbaeva, D., Fitzsimmons, S. & Brewster, C. Beyond the double-edged sword of cultural diversity in teams: Progress, critique, and next steps. J Int Bus Stud 52, 45–55 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00390-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00390-2