Abstract

The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) efforts of brands impact consumers’ willingness to support them, yet consumers are generally skeptical about CSR communication. This empirical work uses three experimental studies to show that framing CSR messages in values-based terms (“It is our duty to engage in this CSR initiative”) enhances consumers’ brand attitudes by increasing perceived moralization and perceived commitment to the initiative. More interestingly, we show that this effect is reversed for highly formalistic consumers (those motivated by the duty to follow values, principles, and rules) who are opposed to the CSR initiative. We also show that in the long term, values-based frames can lead to higher perceived hypocrisy in the eyes of highly formalistic people if the firm does not live up to its lofty principles. This is the first paper to establish the link between values-based CSR communication, perceived moralization, perceived commitment, and brand attitudes. It also brings together the research streams on CSR communication and consumer ethical systems to show that though values-based framing of CSR is a high-return strategy for brands in terms of improved brand attitudes, it is also a high-risk strategy for firms targeting highly formalistic consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Each year, Fortune 500 companies spend over $20 billion on CSR (Meier and Cassar 2018). Increased interest in cause-based brand strategies among firms, and heightened preference for purpose-driven brands among millennial consumers (Schmeltz 2012), has resulted in a growing number of firms basing decisions in the interest of “all stakeholders,” including customers and society writ large (Benoit 2019). This paper investigates how firms can express CSR commitment through values-based framing of CSR communications, and the effectiveness of such an approach on consumer attitudes toward their brands.

We define values-based framing as an approach to CSR communication that emphasizes the moral imperative driving the firm to engage in the CSR activity. This imperative is rooted in the firm’s values and social mission and emphasizes principles rather than social benefits, corporate benefits, or some other aspect of the CSR activity. As an example, Unilever has shown deep commitment to values-based framing of its purpose-driven branding initiatives. CEO Alan Jope has directed the organization to align every Unilever brand with a specific mission. The Dove brand focuses on women’s self-esteem and Ben and Jerry’s is committed to climate-change awareness. On the other hand, Unilever brands like Axe (men’s grooming products) and Knorr (food and beverage) must either align with a specific social purpose or risk being sold off soon (Buckley 2019).

These types of efforts are driven by more than pure altruism, of course. Well executed CSR efforts may lead to positive evaluations of other product attributes. Effective product-level CSR efforts may have a spillover effect on brand portfolios and corporate-level brands (Wang and Korschun 2015) and CSR has been shown to work synergistically with brand equity to enhance firm financial performance (Rahman et al. 2019). However, such benefits of CSR accrue only after a series of specific steps undertaken by the firm and the consumers. These include (1) Actual CSR efforts by the firm, (2) CSR communication to inform consumers about CSR efforts, (3) consumers trusting CSR communication from the firms, and 4) consumers forming perceptions of company as socially responsible. Only then the consumers reward the company with their brand loyalty.

The current research utilizes these steps to examine the effectiveness of values-based frames. We consider the favorable impact of moralized CSR communication (step 2) on enhancing consumer trust (step 3), perceived commitment (step 4), and ultimately brand attitude and loyalty. This approach is a departure from past CSR research that directly explores the linkage between steps one and three and focuses on types of CSR efforts that lead consumers to trust CSR communication. For example, past research has focused on alignment between a firm’s business model and their chosen cause as a key predictor of perceived CSR commitment of the brand (Bigné‐Alcañiz et al. 2009; Menon and Kahn 2003; Simmons and Becker-Olsen 2006). However, we focus on the second step to explore how framing of CSR communication in values-based terms leads to subsequent positive outcomes for the firm in terms of consumers’ perceptions. Additionally, we delineate a boundary condition of this effect by showing that it is reversed if highly formalistic consumers who are opposed to the CSR initiative are targeted. Formalistic consumers are individuals who have an ethical predisposition to formalistic (or deontological) standards of judgement. Formalism is characterized by a tendency to make ethical decisions and judgements based on a set of moral principles (Love et al. 2018, 2015). Highly formalistic people are also more likely to perceive hypocrisy where firms do not live up to their lofty principles, creating an additional long-term risk of using values-based frames.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Our theoretical development section begins with a review of the literature on the crucial role that CSR communication plays in changing perceived commitment and brand attitudes and explores the linkages between values-based framing of CSR communication, perceived moralization, and perceived commitment. Next, we develop our hypotheses related to the positive effect of values-based CSR communication on brand attitudes and the boundary conditions of this effect in terms of consumers’ ethical predisposition and support for the CSR initiative. Then, we explore the long-term consequences of values-based CSR framing for the brand in the case of a statement-behavior mismatch. This is followed by three experimental studies and conclude with a general discussion and implications of our research.

Theoretical development

Benefits of CSR for brands

The way consumers perceive a company’s CSR impacts their willingness to buy and support the company’s brands (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006). Positive beliefs among consumers about CSR lead to greater purchase intention and increased brand affect and loyalty (Bhattacharya and Sen 2004; Bhattacharya et al. 2008; Du et al. 2007; Schmeltz 2012; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), especially for experiential brands (Johnson et al. 2018) and among consumers for whom CSR is important (Ford and Stohl 2019). Swaen and Vanhamme (2004) suggest that communicating a socially responsible image leads to more positive consumer perceptions and greater brand trust, and that the public is increasingly interested in using their power (i.e., dollars) to reward “good” companies and punish “bad” ones (Lewis 2001). For brands like Dove, CSR has become a tool for reinforcing a strong brand identity. However, consumers need to trust CSR communication and infer that a firm is really committed to the cause for it to avoid an “authenticity gap” (Samuel et al. 2018) and be perceived as truly socially responsible. Next, we discuss the role of perceived commitment in enhancing the positive impact of CSR efforts on brand image.

CSR communication and perceived commitment

CSR practices can have a positive impact on brands, but to “reap the benefits that come with such an image” (Jahdi and Acikdilli 2009, p. 106), Du and colleagues (2010) suggest using CSR communication as a tool to enhance perceived CSR commitment. Higher perceived commitment reduces perceptions of bragging (Sen et al. 2009) and translates into a more positive attitude toward the company (Du et al. 2010).

Moreno and Kang (2020) note, “A vast amount of information on corporate transgressions has heightened consumer skepticism about corporate responsibility” (2477). Brands must be purposeful about the ways they communicate their CSR so that their efforts are perceived positively by their target consumers. Poorly executed CSR communication may be perceived as clever marketing (Schlegelmilch and Pollach 2005) which can increase consumer skepticism and loss of trust in firms (Buckley 2019; Igenhoff and Sommer 2011; Samuel et al. 2018). With increased public sensitivity to hypocrisy in CSR and fierce competition in the marketplace, companies must be careful to avoid CSR inconsistencies, since these lead to damaging consumer perceptions of brand hypocrisy (Wagner et al. 2009). This perceived CSR hypocrisy can be difficult to overcome as it sets up the context against which consumers judge future brand actions, so careful communication and framing of CSR activities is crucial (Kim and Ferguson 2018).

Interestingly, even when consumers value CSR, they prefer related information be presented in a factual, rather than general or impressionistic, style (Schmeltz 2012) and these factual communications appear to be particularly convincing to young consumers. But are factual statements alone strong signals of firm commitment?

Authenticity has been shown to effectively enhance perceived commitment to CSR (Perez 2019). Firms may establish authenticity by demonstrating CSR fit with firm values, as consumers more easily find the CSR effort to be justified and logical (Moreno and Kang 2020). We suggest that another way firms may significantly heighten the effect of CSR communication on perceived CSR commitment is by moralizing the communication through values-based framing.

This approach differs from strategies investigated to enhance perceived commitment (Schmeltz 2012) as much of this research focuses on how alignment between business interests and a given social initiative (or perceived CSR fit) impacts perceived CSR commitment of the brand (Bigné‐Alcañiz et al. 2009; Menon and Kahn 2003; Simmons and Becker-Olsen 2006). Forehand and Grier (2003) show that public acknowledgment of the strategic benefits to the brand inhibits CSR skepticism and limits the potential for perceived hypocrisy by signaling that the company is in it for the long haul. Brands that better align their CSR undertakings with their core competencies such as Starbucks’ investment in coffee growing communities (Starbucks 2017) can “create a high perceived fit and hence enjoy greater business returns” (Du et al. 2010, p. 13) while minimizing consumer skepticism (Schmeltz 2012) and avoiding perceptions of hypocritical behavior.

Focusing on the strategic alignment between CSR and business goals is not always feasible or even desirable from a branding standpoint. For example, high-fit CSR efforts by firms in stigmatized industries can lead to increased CSR skepticism (Austin and Gaither 2019). Moreover, brands stay relevant in consumers’ lives by engaging in and contributing to culturally relevant issues of the time. A brand’s cultural assets, including the cultural potential of the brand’s business practices and the brand’s historical cultural expressions (Holt 2012), are what makes a brand’s contribution to such issues credible. This suggests that a brand’s perceived alignment or fit with a cause can go beyond (or perhaps even against) any strategic alignment in the business model if the brand is seen as taking a values-based stand on a cultural issue relevant to the consumers in that product category that is congruent with the brand’s cultural assets. For example, when Dick’s Sporting Goods CEO Ed Stack chose to stop selling assault-style weapons and limited other gun sales in 2019, he knew that this would run counter to the firm’s business interests. “For the fiscal year ending Feb. 2 [2019], same-store sales fell 3.1 percent, according to company earnings. Stack has blamed much of the slump on gun issues” (Siegel 2019). However, by taking a values-based stand, the brand was able to contribute to the cultural conversation on this important issue for the consumers in the category and in the process gained cultural resonance. And the commitment of Unilever’s Ben and Jerry’s to fighting climate change is not obviously based on a strategic connection between ice cream and global warming (if anything, one might expect the opposite as warmer days may increase demand for ice cream). Therefore, additional factors must be considered in CSR communication strategy such as Ben and Jerry’s history of taking values-based stands on issues of social justice since the company’s founding days (Ciszek and Logan 2018). Next, we discuss the role of values-based framing and moralization of CSR in enhancing the perceived commitment of the brand to the CSR cause.

Values-based framing and the moralization of CSR

In this research, we link values-based framing of CSR communication to the degree to which an initiative is perceived by consumers as morally driven for the brand. Rozin (1999) suggests that moralization is “the process through which preferences are converted into values” (218) and that process can yield either a negative or positive moral status. Moralized attitudes are associated with deeper perceived commitment as compared to other strong attitudes (Kreps and Monin 2014; Mullen and Skitka 2006).

Moralization takes more than a generalized impressionistic statement such as, “we are constantly working to reduce our CO2 emissions” (Schmeltz 2012, p. 41). When organizations moralize a CSR initiative, it must lead consumers to assume the firm is highlighting what it values. For example, LEGO states, “We want to play a part in building a sustainable future and making a positive impact on the planet our children will inherit” (Lego 2021) and has created multiple new products and programs to support these efforts. We suggest that a downstream consequence of perceived moralization is perceived commitment of the brand to its CSR initiatives. In turn, perceived CSR commitment of the firm impacts consumer attitudes toward the brand.

Perceived moralization is an important but understudied mediator between CSR communication and brand attitudes. Moral judgements are held with greater conviction than nonmoral judgements. They are also more motivating and less subject to compromise than nonmoral judgements (Ginges et al. 2007; Schein and Gray 2018; Skitka et al. 2005, 2015; Tetlock et al. 2000).

Research in the interpersonal domain has shown that when speakers use a values-based justification for actions, message recipients infer higher perceived moralization and higher perceived commitment to the initiative (Kreps and Monin 2014). We expect that brands using values-based framing of their CSR communications enhance CSR moralization by building a strong CSR-firm values connection (Moreno and Kang 2020). This in turn leads to more positive attitudinal responses via perceived CSR commitment.

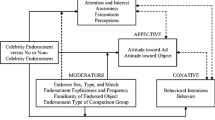

Therefore, we expect values-based framing to lead to higher perceived moralization and perceived commitment in the brand domain, as in Fig. 1.

H1

Values-based framing of CSR communications increases CSR moralization, which in turn leads to higher perceived CSR commitment and more positive brand attitude.

Ethical formalism and formalistic consumers

H1 argues that values-based framing may be effective for communicating CSR-firm values fit, in which recent CSR research has determined to be effective in reducing CSR skepticism (Moreno and Kang 2020). However, this general assertion does not consider individual differences in target customers—another set of underexplored but important factors influencing the effectiveness of CSR communication. While we claim that values-based framing will be a generally effective CSR communication strategy, we further assert that its effect will vary based on the ethical predispositions of message targets.

Given the ethical nature of CSR, ethical predispositions of consumers play a likely role in consumer responses to CSR. The two most ubiquitous ethical standards of judgment are consequentialism and formalism.Footnote 1 Individuals who utilize a consequentialist framework focus on the outcomes of their decisions and actions, while those using a formalistic framework are motivated by the duty to follow values, principles, and rules (Brady and Wheeler 1996; O’Shaughnessy 2002). Combining recent findings in the domain of ethical predispositions with those of CSR, we propose that the ethical predispositions of CSR message recipients (specifically, preferences for formalist criteria for making moral decisions Love et al. 2018, 2015; Reynolds 2008) will interact with values-based frames to influence brand evaluations.

The current research explores the relationship between values-based framing and formalistic standards of judgment.Footnote 2 We propose that even though values-based justifications for CSR initiatives lead to more positive brand attitudes in general, respondents’ level of formalism and their support for the CSR initiative may moderate this effect. When a firm presents values-based justifications to highly formalistic consumers, those justifications highlight the precise judgement criteria that resonates with those consumers, enhancing the fluency with which they process the message. When these consumers support the initiative, this processing fluency leads to more positive evaluations of the brand.

Furthermore, formalistic judgments, unlike consequentialist judgements, tend to be more automatic (and less evaluative) Type 1 processes (Greene 2007; Greene et al. 2001, 2004, 2008; Kahneman 2003; Oppenheimer 2008; Winkielman et al. 2003). This suggests that formalists are in general more susceptible to message framing effects as their judgement criteria do not engender careful evaluation of message content. The aforementioned processing fluency leads to increased judgments of truth, goodness, and preference, particularly when Type 1 processes are operational (Winkielman et al. 2003).

However, as Rokeach (1973) and others have noted, attitudes are a function of values. This suggests that, if a formalistic consumer opposes the CSR message, a values-based frame will lead to a more negative consumer evaluation. Moralization may actually be counter-productive, leading to more negative brand attitudes as feelings about the message are transferred to the brand. In this case, moralization exacerbates the expected negative consumer response to a firm supporting an issue that the consumer opposes as the fluency of the frame makes prior negative moral judgements more accessible.

In other words, by making the consumer’s prior judgments more accessible, increased moralization may result in a more moralized response. This moralized response by formalists who oppose the CSR issue will be negative, and more strongly so because of the moralized nature of formalistic judgement. For example, a firm might indicate its commitment to gun control is based on a principled belief that gun control is an important issue to support, i.e., a belief that this is the right thing to do based on its corporate values. To a formalistic consumer who supports gun ownership rights, this values-based frame will only make their own principled opposition more accessible, and the firm’s position less justifiable. Thus, a values-based frame creates an unexpected short-term risk for brands.

H2a

For a brand engaging in CSR, formalistic individuals respond more favorably to a values-based frames (as compared to no justification) when they support the CSR initiative.

H2b

For a brand engaging in CSR, formalistic individuals respond less favorably to a values-based frames (as compared to no justification) when they are against the CSR initiative.

Long-term effects of values-based frames

All of us, together with our investors, customers and supply partners, have the right to expect Papa John’s to conduct its business lawfully, responsibly and with the highest moral and ethical standards. -John Schnatter, Founder and former CEO (Papa John’s Code of Ethics and Business Conduct, 2018).Footnote 3

Values-based CSR frames may expose brands to long-term risks. Once a brand commits to a particular CSR initiative and makes it known publicly (Cialidini and Trost 1998), it is difficult to change course. Were Dick’s Sporting Goods to resume sales of assault-style weapons, gun-control advocates would likely protest the move as a grossly hypocritical violation of principles, and there is no guarantee that the guns-rights advocates who had previously abandoned the company would return. According to Wagner and colleagues (2009), perceptions of hypocrisy stem from a firm claiming to be something that it is not. Relatedly, skepticism regarding the motivations behind CSR efforts undermines the firm credibility (Schmeltz 2012). This greatly reduces the positive benefit of CSR in terms of perceived morality, brand loyalty, and purchase intention.

When a firm moralizes its behavior in relation to an issue, the firm increases its vulnerability to future perceptions of hypocrisy when supporting the cause is no longer in the best interest of the brand (Kreps et al. 2017). This exposure to perceived hypocrisy is greatest for firms with formalistic consumers. Since consistency in the application of moral rules is a defining characteristic of formalism (Brady 1990), formalists tend to be particularly sensitive to inconsistencies in ethical conduct, which they associate with violations of moral rules. As a result, inconsistencies between formalistically professed brand values and firm conduct may result in a particularly strong negative reaction among formalistic consumers. In essence, the consumers most sensitive to values-based frames are also the consumers who would be most negatively influenced by future behaviors inconsistent with those frames.

H3

When there is an inconsistency between the brand’s behavior and statements, formalistic individuals perceive a brand using values-based frames (as compared to no justification) as more hypocritical.

Study 1

The purpose of Study 1 is to test the proposition that values-based framing of CSR enhances perceived moralization and perceived commitment of the firm to the initiative and consequently, improves brand attitude (H1).

Method, participants and design

Two hundred and four US-based Amazon Mechanical Turk workers participated for payment. Mturk participants have been shown to be fairly diverse and representative of the general population (Landers and Behrend 2015). Sensitivity analyses showed that this sample size is sufficient to detect a small-to-medium effect size at 95% power (Faul et al. 2007). We excluded data from 19 participants who did not respond correctly to an attention check. Thus, the final sample size for this study was 185 participants (103 female; Mage = 46.49). Respondents were randomly assigned in Qualtrics into one of two experimental conditions based on the CSR justification (values-based justification vs. no justification). The manipulation is described below for this posttest-only experiment. The procedure, stimuli, and measures were adapted from Kreps and Monin (2014). We manipulated the presence (versus absence) of a values-based justification for a brand’s CSR initiatives. Based on a manipulation check (“Please rate your agreement with the following statement about J&T’s attitude toward this initiative: ‘It is consistent with principles one has to follow’”) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), respondents perceived a significantly more values-based justification in the values-based condition than in the control condition (M = 5.38 vs. 4.92, p < 0.05).

Procedure and stimuli

Participants read and answered questions about a fictitious clothing brand, Jones and Thompson (J&T), that had decided to double its yearly budget allocated to a CSR initiative focused on combating climate change. Participants were asked to read an excerpt from a newspaper article in which J&T’s CEO shared his thoughts about the new initiative. The CEO announced the initiative and provided either no justification, or a values-based justification for these CSR efforts. The justifications were successfully used in past work (Kreps and Monin 2014) and are provided in Appendix 1.

Measures

After reading the newspaper excerpt, participants answered several questions on scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) measuring perceived moralization of the initiative for J&T, J&T’s perceived commitment to the initiative, and attitude toward the J&T brand. Specific scale items, coefficient alphas, and scale sources are in Appendix 2.

Results and discussion

We found a main effect of values-based justification on perceived moralization (F (1183) = 4.99; p < 0.05) such that perceived moralization for the values-based justification (M = 5.33) was higher as compared to the no justification condition (M = 4.98). There was also a main effect of values-based justification on perceived commitment (F (1183) = 6.63; p < 0.05) such that perceived commitment for the values-based justification (M = 5.46) was higher as compared to the no justification condition (M = 5.09). Finally, there was a main effect of values-based justification on attitude toward the brand (F (1183) = 6.14; p < 0.05) such that the attitude was more positive for the values-based justification (M = 5.82) as compared to the no justification condition (M = 5.38).

To test whether the effects of values-based CSR framing on attitude toward the brand is mediated by perceived commitment to the cause via perceived moralization, we explored a sequential mediation model (Model 6) using the bootstrapping procedure in SPSS PROCESS (Hayes 2017) with presence (vs. absence) of a values-based justification as the independent variable, attitude toward the brand as the dependent variable, and perceived moralization and perceived commitment as the two serial mediators.

Consistent with our prediction in H1, the indirect effect of values-based framing on brand attitude through perceived moralization and perceived commitment was significant: the 95% confidence interval (CI) around the estimate excluded zero (B = 0.14; SE = 0.06; 95% bootstrap CI: 0.02 to 0.26). We find no direct effect of a values-based justification on attitude toward the brand (B = 0.09, SE = 0.12, 95% bootstrap CI: − 0.16 to 0.33). Using a values-based justification for CSR efforts only leads to favorable brand attitudes via perceived moralization and perceived commitment toward the initiative.

Summary findings

This study illustrates that brands are generally better off explaining their CSR efforts in values-based terms. Values-based framing of CSR communication leads to higher perceived moralization, and this increase in perceived moralization leads to higher perceived commitment and a more positive attitude toward the brand. However, could there be instances where a values-based frame for CSR communication might backfire? To test this, we measured respondents’ ethical predispositions as well as their support for the CSR initiative in our next study.

Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 is twofold. First, we test whether respondent formalism generally predicts a more favorable response to values-based framing of CSR they support (H2a). Second, we test whether this effect is reversed (which is to say that formalism predicts a more negative response) when the respondent opposes the CSR effort (H2b).

Method, participants and design

Two hundred and six US-based Amazon Mechanical Turk workers participated for payment. Sensitivity analyses showed that this sample size is sufficient to detect a small-to-medium effect size at 95% power (Faul et al. 2007). We excluded data from six participants who did not respond correctly to an attention check, resulting in a net sample size of 200 participants (93 female; Mage = 36.33). The procedure, stimuli, and measures were the same as Study 1 with the only difference being that our cover story for this study did not mention any specific CSR domain but focused on CSR efforts in general to ensure generalizability. We manipulated the type of justification for a factual CSR initiative (no justification, values-based) and measured participants’ ethical predispositions as well as support for CSR (Connors et al. 2017; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001).

Procedure and stimuli

Participants read and answered questions about the same fictitious clothing brand (J&T) that decided to double its yearly budget allocated to CSR initiatives. As in Study 1, participants were asked to read an excerpt from a newspaper article in which J&T’s CEO provided either no justification or a values-based justification for the initiative. Using the same manipulation check as in Study 1, we found that respondents perceived a significantly more values-based justification in the values-based condition than in the control condition (M = 5.50 vs. 4.95, p < 0.01).

Measures

After reading the newspaper excerpt, participants answered several questions.

on scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) measuring perceived moralization of the initiative for J&T, J&T’s perceived commitment to the initiative, and attitude toward the J&T brand. Next, we measured participants’ ethical predispositions as well as support for CSR (see Appendix 2 for specific scale items, coefficient alphas, and scale sources).

Results and discussion

We used Preacher and Hayes (2008) Process Model 3 to test the three-way interaction between support for the CSR initiative, values-based framing, and respondent level of formalism. Process Model 3 tests the conditional effects of an independent variable X (type of justification was coded as values-based = 1 and no justification = 0) on dependent variable Y given two moderator variables M (participants’ levels of formalism) and W (support for CSR) such that Y = α + b1X + b2M + b3W + b4XM + b5XW + b6MW + b7XMW + e. The conditional effect of X on Y = b1 + b4M + b5W + b7MW. Participants’ level of consequentialism was included as a covariate, and perceived moralization, perceived commitment, and attitude toward the brand were tested as the dependent variables (Y).

As hypothesized, we found a three-way interaction effect on perceived moralization (β = 0.31, t = 2.06, p < 0.05) such that for respondents who supported the CSR initiative, values-based framing led to more positive effects (as compared to no justification) irrespective of their level of formalism. However, for respondents who do not support the CSR initiative (i.e., those who are either neutral or opposed to the initiative), values-based framing led to more positive effects only for less formalistic individuals. To identify the range of values of support for CSR for which there was a negative interaction effect between a values-based justification and formalism, we used the Johnson–Neyman technique (Spiller et al. 2013). The Johnson–Neyman “floodlight test” is used to identify regions of independent variable values for which a manipulation has a significant effect on a dependent variable. This analysis revealed that as respondents’ formalism increased, they perceived a values-based justification as less moralized compared to no justification when their mean-centered support for CSR is less than 0.41 (bJN = − 0.39, SE = 0.2, p < 0.05). This suggests that providing values-based justifications to highly formalistic people opposed to an initiative can actually reduce the level of perceived moral conviction of the firm. This effect is highlighted in Figs. 2a–c.

Similarly, and as shown in Figs. 3a–c, we found a three-way interaction for perceived commitment (β = 0.43, t = 3.25, p < 0.005) such that as respondents’ formalism increased, they perceived the brand providing a values-based justification as less committed to CSR when the respondent’s mean-centered support for CSR was less than 0.40 (bJN = − 0.33, SE = 0.17, p < 0.05), suggesting that providing values-based justifications reduces perceived commitment for highly formalistic people when they are opposed to the CSR initiative. Also, as shown in Figs. 4a–c, though the three-way interaction failed to reach significance for brand attitude (β = 0.23, t = 1.51, p = 0.13), Johnson–Neyman analysis revealed that as respondents’ formalism increased, they liked the brand providing a values-based justification less compared to one providing no justification when their mean-centered support for CSR was less than 0.60 (bJN = − 0.41, SE = 0.21, p < 0.05). Values-based justifications lead to less favorable brand attitudes for highly formalistic people when they are opposed to an initiative.

Summary findings

For respondents in agreement with the CSR initiative, values-based framing increased perceived moralization, perceived commitment, and brand attitude regardless of respondents’ levels of formalism, and so hypothesis 2a was not supported. However, these findings do strongly support hypothesis 2b, as the values-based frame negatively impacted perceived moralization, perceived commitment, and brand attitude for more formalistic consumers who did not agree with the CSR initiative. Study 2 also replicates the findings of study 1 and so offers additional support for hypothesis 1.

Study 3

The purpose of Study 3 is to evaluate the long-term consequences of values-based frames. We investigate the impacts of CSR messaging and behavioral inconsistencies on formalistic consumers (H3).

Method, participants and design

Two hundred and five US-based Amazon Mechanical Turk workers participated in Study 3 for payment. Sensitivity analyses showed that this sample size is sufficient to detect a small-to-medium effect size at 95% power (Faul et al. 2007). We excluded data from fifteen participants who did not respond correctly to an attention check, leaving a final sample size of 190 participants (82 female; Mage = 47.69). The procedure and stimuli used in the previous studies were modified in order to allow respondents to make hypocrisy judgments. Using the same manipulation check used in Study 1, we found that respondents perceived significantly more values-based justification in the values-based condition than in the control condition (M = 5.42 vs. 4.69, p < 0.01).

Procedure and stimuli

As before, participants were told that they would be reading an excerpt from a newspaper article published last year in which J&T’s CEO had shared his thoughts about an initiative to double its yearly budget allocated to CSR. The CEO announced the initiative and provided either no justification or a values-based justification for these CSR efforts. Next, participants were told that they would be reading a second excerpt published today about J&T. This excerpt discussed how J&T was lagging behind other similarly successful clothing brands in terms of its CSR investments. The stimuli were adapted from previous studies (Wagner et al. 2009) and are provided in Appendix 1.

Measures

After reading the second newspaper excerpt, participants answered several questions.

on scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) measuring perceived hypocrisy of J&T (Wagner et al. 2009) and participants’ ethical orientations (see Appendix 2 for specific scale items, coefficient alphas, and scale sources).

Results and discussion

To evaluate the effects of CSR inconsistencies on different types of consumers, we used Preacher and Hayes (2008) Process Model 1 with the dichotomous values-based justification variable (coded as values-based condition = 1) as the independent variable, participants’ levels of formalism as the moderator, and perceived hypocrisy of the brand as the dependent variable (participants’ consequentialism was included in the model as a covariate). As predicted, there was a two-way interaction effect on perceived hypocrisy (β = 0.17, t = 2.33, p < 0.05). To identify the range of values of formalism for which a values-based justification (as compared to no justification) led to higher perceived hypocrisy, we used the Johnson–Neyman technique (Spiller et al. 2013). This analysis revealed that as respondents’ mean-centered formalism became higher than 0.03 (bJN = 0.17, SE = 0.08, p < 0.05), they perceived a values-based justification as more hypocritical compared to no justification. This suggests that providing no justification (as compared to a values-based justification) works better for highly formalistic people when there is a possibility of inconsistency between the brand’s moral behavior and stated standards in the long term. This effect is highlighted in Fig. 5.

Summary findings

In support of hypothesis 3, formalistic consumers perceived more hypocrisy in firms that use values-based framing for the promotion of CSR goals that they do not subsequently fulfill. This provides another important reason that firms should be cautious about using values-based frames.

General discussion

While there is not a “one size fits all” option when it comes to how brands should frame and communicate their CSR programs, moralization clearly plays a nuanced role in CSR framing. Furthermore, firms must be cognizant of audience traits beyond mere support for CSR and the ethical formalism of target consumers should also be considered an important factor influencing assessment of CSR communications. In Study 1, we show that values-based framing of factual CSR communications generally leads to more favorable brand attitudes, particularly in the short-term. This enhancement of brand attitude is mediated by perceived moralization and perceived commitment of the brand to the CSR cause. Perceived moralization has been an understudied mediator in the CSR domain, particularly because of a distinct focus on self-interested rationales for doing good (implicit in the often-used saying, “doing well by doing good”) (Kreps and Monin 2011), and prior research that has highlighted the effectiveness of factual rather than general claims about CSR (Schmeltz 2012).

In Study 2, we delineate an important boundary condition of our primary finding by exploring the complex interaction between moralization through values-based frames and the level of audience formalism. While formalism enhances the effectiveness of values-based frames where the target audience supports the CSR, the effect of such frames on brand attitude is negative for highly formalistic people if they are opposed to the CSR initiative.

In Study 3, we find that values-based framing of initiatives can create risks for brands in the long term, as consumers perceive this moralization as a signal of commitment to the issue for the brand. This commitment can constrain brands because if any deviation from their stated position becomes known, it can lead to perceptions of hypocrisy (Kreps et al. 2017). Therefore, though values-based framing of CSR is a high-return strategy for brands in terms of improved brand attitudes, it is also a higher-risk strategy as a potential statement-behavior mismatch in the future may generate perceptions of brand hypocrisy.

Our results contribute to the existing literature (Du et al. 2010; Wagner et al. 2009) that suggests that the way CSR is framed and communicated to the public is exceedingly important for how the brand is viewed by consumers. Our first study highlights the general benefits that framing CSR communication in principled terms can have. Consumers construe the values-based “it is our duty to engage in CSR” approach as an indication of moralization and commitment to the initiative, and this creates a positive attitude toward the brand. Normatively, if a consumer cares deeply about an initiative, the moralization of the issue by the brand should be relatively unimportant; what should matter is that they invest at all. We believe that consumers care about moralization for two reasons. First, they admire the brand for standing by its principles (a form of brand anthropomorphization) (Kervyn et al. 2012), and second, they expect that firm will be more prone to continue such efforts in the future.

We also recognize that this values-based approach to CSR is not appropriate in all cases. Individual ethical predispositions play a crucial role in the way consumers process and interpret CSR messaging. Formalistic individuals (those that focus on duty as a driver of behavior) need to be carefully considered when brands select their CSR initiatives. Formalists are often described as lacking nuance in their opinions and decision-making. Prior research has shown that formalism is negatively associated with openness to change and positively associated with need for cognitive closure (Love et al. 2015). This suggests that highly formalistic individuals show greater reluctance to accept new ideas and are less comfortable with ambiguity. Therefore, they might favor established positions and could be less persuadable when their position has already been established. All of this clearly presents a challenge for firms (or communicators in general) who might try to persuade formalists.

One might conclude that the only way to persuade a formalist would be to match message framing to their predispositions, i.e., frame arguments in values-based terms. However, our research shows that using a values-based justification for an action that is not in line with a particular group’s ideas of what is “moral” can backfire. In other words, if a firm were to commit to a CSR program in support of wearing a face covering to prevent the spread of Covid-19 and justify it in terms of it being their duty, a formalist who is committed to “personal freedom” would take serious issue with that approach. In fact, from the perspective of the formalist consumer with opposing beliefs, it would be better if the firm that committed itself to wearing a face covering provided no justification at all for their position on the issue.

Theoretical contributions

The current research makes two important contributions. First, we show that a common research finding, that matching the message frame with message recipients leads to more positive evaluations (Bigné‐Alcañiz et al. 2009; Connors et al. 2017; Lee and Aaker 2004; Wheeler et al. 2005), does not always hold for specific populations of consumers (i.e., highly formalistic individuals). Values-based justifications (as compared to no justifications) for CSR efforts may backfire for formalists who are against the CSR initiative. This adds greater theoretical nuance to the general findings that suggest any justification for CSR could be better than no justification (Langer et al. 1978), as well as that message matching to recipients always leads to positive evaluations. Second, in contrast to the short-term beneficial consequences of values-based framing of CSR on brand attitudes, we show the long-term detrimental consequences of such framing in terms of perceived hypocrisy in the case of a statement-behavior mismatch. By taking a long-term perspective, we show that though brands can boost consumers’ attitudes toward them by moralizing an initiative via values-based framing, such framing can also constrain brands in terms of possible future courses of action. Formalistic consumers are particularly harsh in their judgments of a brand’s perceived hypocrisy if the brand has used values-based frames in the past. This research has important practical implications not only in terms of more effective CSR communication but in any context where formalistic individuals need to be persuaded, such as in politics, public policy, law, or management.

Practical implications

In a recent The New York Times guest essay entitled, “We’re Ben and Jerry. Men of Ice Cream, Men of Principle,” Bennett Cohen and Jerry Greenfield (the ice-cream making founders of Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Holdings) praise their former company’s recent decision to stop selling ice-cream in the occupied territories as a “decision to more fully align its operations with its values” (Cohen and Greenfield 2021). And it is not just Unilever’s Ben & Jerry’s that is moralizing its social initiatives. Large-scale brands across a variety of industries including apparel (Patagonia, REI), footwear (Nike, TOMS), personal care (Unilever’s Dove and many of their other brands), and many others effectively use values-based framing to enhance perceived commitment to their CSR efforts.

Chick-fil-A has used a values-based framing for both its mission statement—“to glorify God and be a faithful steward of all that is entrusted to us” and its decision to close all its stores on Sunday by proclaiming that this decision was a testament to their founder’s faith in God (Valle 2019). However, Chick-fil-A’s donations to organizations opposing same-sex marriage were also interpreted in light of their founder’s values-based statements about his belief in the “biblical definition of the family unit.” Though such statements invited swift condemnation and boycott from liberal consumers, media, and activists, their support increased among more formalistic and conservative consumers. Moreover, despite the widespread criticism among liberal consumers, the company continued to grow its sales and store locations and is the most profitable fast-food chain in the country on a per-location basis (Valle 2019). As they kept on expanding to more liberal cities such as New York and decided to stop giving money to conservative organizations they supported earlier, the company did not give any values-based justification for stopping their donations and instead talked about their changed CSR focus on three initiatives only: education, homelessness, and hunger (Yaffe-Bellany 2019). This suggests that the brand paid attention to the ethical predispositions of their current and prospective consumers in not only deciding what causes to support but also what type of justifications to use for their actions. As they expanded to more liberal locations, they not only stopped supporting organizations opposing same-sex marriage but also stopped using any values-based justifications for these changes.

These findings also have implications for a wide variety of industries since CSR continues to increase in importance as its visibility grows. Perhaps the most notable impact is that firms need to understand that they cannot moralize a CSR initiative without knowing the ethical leanings of their core consumers. As with the face covering example above, engaging in morally (or politically) divisive CSR programs carries risk and any firm that decides to do so is better off paying attention to the ethical predispositions of its core consumers. While formalistic tendencies may be difficult to identify directly among groups of consumers, prior research has shown the construct to be highly correlated with other, more easily identifiable traits. Most notably, increasing levels of both religiosity and political conservativism (Hannikainen et al. 2017; Love et al. 2018; Piazza and Sousa 2014) predict formalism. Political conservativism may be particularly useful as an identifier, since political orientation may be predicted based on geographic location, prior purchases, and online behavior (Jost 2017).

CSR aside, there is also an opportunity for research into how communicators, be it politicians, lawyers or managers, can better frame their moral messaging in order to persuade message recipients while paying particular attention to the recipients’ ethical predispositions. The current political landscape offers occasion to better communicate messages around moral and amoral initiatives and a special consideration of avoiding hypocritical communication would be welcome in today’s climate.

This is not to say that we recommend that firms avoid taking strong, principled stands on initiatives that are relevant to their mission. On the contrary, such efforts can be effective means to enhance brand consistency and relevance. The firm must recognize, however, that principled stands may limit future growth opportunities and possibly alienate a segment of existing customers.

Limitations

We acknowledge that there is some concern about the use of online samples and their potential impact on generalizability. However, research on MTurk shows that these samples are comparable to respondents on other platforms (Huff and Tingley 2015) and that the MTurk subjects are actually more attentive than traditional subject pool participants (Hauser and Schwarz 2016). Additionally, MTurk participants have been found to be “relevant in relation to certain types of research and research questions, especially experimental designs where citizen perception, reactions, and responses are of interest to the researchers” (Stritch et al. 2017, p. 503) which makes it a fit for the current work.

Many of the examples we present in this article deal with well-known Fortune 500 brands. These brands offer some of the most well-known and accessible examples of values-based framing of CSR efforts. However, our studies show that values-based framing may be effective in raising perceived commitment in unknown brands such as the fictitious J&T that we used in our studies. Future tests of values-based framing using well-known global brands may offer additional, more nuanced findings related to its effectiveness and long-term effects on the brand.

Future research directions

Our research points to the need for additional work on the impact of values-based message framing in general. Firms and brands often give reasons to justify their actions to consumers. For example, a retail store might decide to stop providing plastic bags to consumers or a hotel chain might decide to encourage guests to reuse their towels. Our research shows that the justification surrounding these actions can have implications for consumers’ attitudes toward brands and their perceptions of the organization’s hypocrisy. In addition to values-based framing of specific actions, brands can strategically position themselves around specific principles and values. Brands such as Patagonia, Dove, and even Old Spice are recognized by their brand positioning around sustainability, self-esteem, and confidence even more than their specific product categories. Our research suggests that such positioning could be brand enhancing not only for the content of the position, but for the values-based framing of the position. However, the values-based framing of the brand position may also pose some surprising risks for the brand. In particular, such framing constrains the brand in terms of future courses of action and leaves the brand particularly vulnerable to charges of hypocrisy. Therefore, values-based framing of a brand’s positioning can be seen as a high-return high-risk strategy that should be engaged in only when the entire business model is capable of credibly delivering on that positioning. Any cracks in the delivery of that positioning can make the brand seem hypocritical particularly because the brand has moralized its stated positions by using a values-based framing. Though employees are important stakeholders responsible for delivering on a brand’s moral positioning, past research has suggested that corporate moral branding can seem too centralized and constraining to employees resulting in demotivation (Morsing 2006). We hope that future researchers will explore how ethical predispositions of not just consumers but employees impact both a brand’s moral positioning and delivery of that positioning in the marketplace.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that brands benefit from framing CSR efforts in values-based (i.e., formalistic) terms, but that doing so can expose the firm to short- and long-term risks. In the short term, values-based framing may actually alienate the brand’s most principled consumers if the CSR efforts being undertaken does not align with the values of those consumers. In the long term, such framing increases perceptions of brand hypocrisy when the brand changes course or does not live up to its lofty principles. These challenges notwithstanding, the more firms focus on aligning their CSR efforts with their consumers’ values the better able they will be to capitalize on brand loyalty.

Notes

We acknowledge that other frameworks exist, but it has been argued that all ethical approaches can be placed under one of these two broad categories (Nozick 1981).

While researchers have often treated formalism and consequentialism as competing standards, which fall on a continuum, there is substantial evidence that these are, in fact, independent constructs (Brady 1990; Brady and Wheeler 1996; Burton et al. 2006; Conway and Gawronski 2013; Greene et al. 2008; Love et al. 2018; Love et al. 2015; Pearsall and Ellis 2011; Reynolds 2008; Reynolds and Ceranic 2007). It is possible, for example, for an individual to prefer highly formalistic as well as consequentialist standards of judgment. Therefore, as a precaution, we tested and controlled for consumer consequentialism in each of our studies. Consequentialism did not affect our findings.

In December of 2017, Schnatter resigned from his position of CEO after condemning the national anthem protests in the NFL and in July of 2018, he resigned from his position as Chairman of the Board after being recorded using a racial slur during a conference call.

Abbreviations

- CSR:

-

Corporate social responsibility

References

Austin, L., and B.M. Gaither. 2019. Redefining fit: Examining CSR company-issue fit in stigmatized industries. Journal of Brand Management 26 (1): 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0107-3.

Benoit, D. 2019. Top CEOs see a duty beyond shareholders. Wall Street Journal, August 20. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.wwu.edu/docview/2275787286?accountid=15006

Bhattacharya, C.B., Sen, S., Korschun, D. 2008. Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Management Review 49(2).

Bhattacharya, C.B., and S. Sen. 2004. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review 47 (1): 9–24.

Bigné-Alcañiz, E., R. Currás-Pérez, and I. Sánchez-García. 2009. Brand credibility in cause-related marketing: The moderating role of consumer values. Journal of Product and Brand Management 18 (6): 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420910989758.

Brady, F.N. 1990. Ethical managing: Rules and results. New Delhi: Indo American Books.

Brady, F.N., and G.E. Wheeler. 1996. An empirical study of ethical predispositions. Journal of Business Ethics 15 (9): 927–940.

Buckley, T. 2019. But is it good? Bloomberg Businessweek 4626: 14–16.

Burton, B., C. Dunn, and M. Goldsby. 2006. Moral pluralism in business ethics education: It is about time. Journal of Management Education 30 (1): 90–105.

Cialdini, R.B., and M.R. Trost. 1998. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In The handbook of social psychology, vol. 2, 4th ed., ed. D.T. Gilbert, S.T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey, 151–192. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ciszek, E., and N. Logan. 2018. Challenging the dialogic promise: How Ben and Jerry’s support for black lives matter fosters dissensus on social media. Journal of Public Relations Research 30 (3): 115–127.

Cohen, B., Greenfield, J. 2021. We’re Ben and Jerry. Men of ice cream, men of principle.: Guest essay. New York Times (Online).

Connors, S., S. Anderson-MacDonald, and M. Thomson. 2017. Overcoming the “window dressing” effect: Mitigating the negative effects of inherent skepticism towards corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 145 (3): 599–621.

Conway, P., and B. Gawronski. 2013. Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in moral decision making: A process dissociation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104 (2): 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031021.

Du, S., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S. Sen. 2007. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing 24 (3): 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2007.01.001.

Du, S., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S. Sen. 2010. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management Reviews 12 (1): 8–19.

Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39 (2): 175–191.

Ford, B.R., and C. Stohl. 2019. Does CSR Matter? A longitudinal analysis of product reviews for CSR-associated brands. Journal of Brand Management 26 (1): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0108-2.

Forehand, M.R., and S. Grier. 2003. When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Psychology 13 (3): 349–356.

Ginges, J., S. Atran, D. Medin, and K. Shikaki. 2007. Sacred bounds on rational resolution of violent political conflict. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (18): 7357–7360. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701768104.

Greene, J.D. 2007. Why are VMPFC patients more utilitarian? A dual-process theory of moral judgment explains. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11 (8): 322–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.004.

Greene, J.D., R.B. Sommerville, L.E. Nystrom, J.M. Darley, and J.D. Cohen. 2001. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293 (5537): 2105–2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062872.

Greene, J.D., L.E. Nystrom, A.D. Engell, J.M. Darley, and J.D. Cohen. 2004. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron 44 (2): 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027.

Greene, J.D., S.A. Morelli, K. Lowenberg, L.E. Nvstrom, and J.D. Cohen. 2008. Cognitive load selectively interferes with utilitarian moral judgment. Cognition 107 (3): 1144–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.004.

Hannikainen, I.R., R.M. Miller, and F.A. Cushman. 2017. Act versus impact: Conservatives and liberals exhibit different structural emphases in moral judgment. Ratio 30 (4): 462–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/rati.12162.

Hauser, D.J., and N. Schwarz. 2016. Attentive Turkers: MTurk participants perform better on online attention checks than do subject pool participants. Behavior Research Methods 48 (1): 400–407.

Hayes, A.F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

Holt, D.B. 2012. Cultural brand strategy. In Handbook of marketing strategy, ed. V. Shankar and G.S. Carpenter, 306–317. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Huff, C., and D. Tingley. 2015. “Who are these people?” Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Research & Politics 2 (3): 2053168015604648.

Ingenhoff, D., and K. Sommer. 2011. Corporate social responsibility communication: A multi-method approach on stakeholder expectations and managers’ intentions. Journal of Corporate Citizenship 42: 73–91.

Jahdi, K.S., and G. Acikdilli. 2009. Marketing communications and corporate social responsibility (CSR): Marriage of convenience or shotgun wedding? Journal of Business Ethics 88 (1): 103–113.

Johnson, Z.S., Y.J. Lee, and M.T. Ashoori. 2018. Brand associations: The value of ability versus social responsibility depends on consumer goals. Journal of Brand Management 25 (1): 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0070-4.

Jost, J.T. 2017. The marketplace of ideology: “Elective affinities” in political psychology and their implications for consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology 27 (4): 502–520.

Kahneman, D. 2003. A perspective on judgment and choice - Mapping bounded rationality. American Psychologist 58 (9): 697–720. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.58.9.697.

Kervyn, N., S.T. Fiske, and C. Malone. 2012. Brands as intentional agents framework: How perceived intentions and ability can map brand perception. Journal of Consumer Psychology 22 (2): 166–176.

Kim, S., and M.A.T. Ferguson. 2018. Dimensions of effective CSR communication based on public expectations. Journal of Marketing Communications 24 (6): 549–567.

Kreps, T.A., and B. Monin. 2011. “Doing well by doing good”? Ambivalent moral framing in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior 31: 99–123.

Kreps, T.A., and B. Monin. 2014. Core values versus common sense: Consequentialist views appear less rooted in morality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40 (11): 1529–1542.

Kreps, T.A., K. Laurin, and A.C. Merritt. 2017. Hypocritical flip-flop, or courageous evolution? When leaders change their moral minds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113 (5): 730.

Landers, R.N., and T.S. Behrend. 2015. An inconvenient truth: Arbitrary distinctions between organizational, Mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 8 (2): 142–164.

Langer, E.J., A. Blank, and B. Chanowitz. 1978. The mindlessness of ostensibly thoughtful action: The role of “placebic” information in interpersonal interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36 (6): 635.

Lee, A.Y., and J.L. Aaker. 2004. Bringing the frame into focus: The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 86 (2): 205.

Lego. 2021. About us. https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/sustainability/environment/

Lewis S. 2001. Measuring corporate reputation. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 6: 31–35.

Love, E., Staton, M., Rotman, J.D. 2015. Loyalty as a matter of principle: the influence of standards of judgment on customer loyalty. Marketing Letters 1–14

Love, E., Salinas, T.C., Rotman, J.D. 2018 The ethical standards of judgment questionnaire: development and validation of independent measures of formalism and consequentialism. Journal of Business Ethics 1–18.

Luo, X., and C.B. Bhattacharya. 2006. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing 70 (4): 1–18.

Meier, S., Cassar, L. 2018. Stop talking about how CSR helps your bottom line. Harvard Business Review 31.

Menon, S., and B.E. Kahn. 2003. Corporate sponsorships of philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of sponsor brand? Journal of Consumer Psychology 13 (3): 316–327.

Moreno, F., and J. Kang. 2020. How to alleviate consumer skepticism concerning corporate responsibility: The role of content and delivery in CSR communications. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27 (6): 2477–2490. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1969.

Morsing, M. 2006. Corporate moral branding: Limits to aligning employees. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 11 (2): 97–108.

Mullen, E., and L.J. Skitka. 2006. Exploring the psychological underpinnings of the moral mandate effect: Motivated reasoning, group differentiation, or anger? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (4): 629.

O’Shaughnessy, N. 2002. Toward an ethical framework for political marketing. Psychology and Marketing 19 (12): 1079–1094.

Oppenheimer, D.M. 2008. The secret life of fluency. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 12 (6): 237–241.

Pearsall, M.J., and A.P.J. Ellis. 2011. Thick as thieves: The effects of ethical orientation and psychological safety on unethical team behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology 96 (2): 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021503.

Perez, A. 2019. Building a theoretical framework of message authenticity in CSR communication. Corporate Communications 24 (2): 334–350. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccij-04-2018-0051.

Piazza, J., and P. Sousa. 2014. Religiosity, political orientation, and consequentialist moral thinking. Social Psychological and Personality Science 5 (3): 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613492826.

Preacher, K.J., and A.F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40 (3): 879–891.

Rahman, M., M.A. Rodriguez-Serrano, and M. Lambkin. 2019. Brand equity and firm performance: The complementary role of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Brand Management 26 (6): 691–704. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-019-00155-9.

Reynolds, S.J. 2008. Moral attentiveness: Who pays attention to the moral aspects of life? Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (5): 1027–1041.

Reynolds, S.J., and T.L. Ceranic. 2007. The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology 92 (6): 1610–1624. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1610.

Rokeach, M. 1973. The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Rozin, P. 1999. The process of moralization. Psychological Science 10 (3): 218–221.

Samuel, A., D. Taylor, G.R.T. White, and M. Norris. 2018. Unpacking the authenticity gap in corporate social responsibility: Lessons learned from Levi’s ‘Go Forth Braddock’ campaign. Journal of Brand Management 25 (1): 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-017-0067-z.

Schein, C., and K. Gray. 2018. The theory of dyadic morality: Reinventing moral judgment by redefining harm. Personality and Social Psychology Review 22 (1): 32–70.

Schlegelmilch, B.B., and I. Pollach. 2005. The perils and opportunities of communicating corporate ethics. Journal of Marketing Management 21 (3–4): 267–290.

Schmeltz, L. 2012. Consumer-oriented CSR communication: Focusing on ability or morality? Corporate Communications: An International Journal 17 (1): 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281211196344.

Sen, S., and C.B. Bhattacharya. 2001. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2): 225–243.

Sen, S., Du, S., Bhattacharya, C.B. 2009. Building brand relationships through corporate social responsibility. In Handbook of Brand Relationships, 195–211.

Siegel, R. (2019) Dick’s Sporting Goods overhauled its gun policies after Parkland. The CEO didn’t stop there. The Washington Post.

Simmons, C.J., and K.L. Becker-Olsen. 2006. Achieving marketing objectives through social sponsorships. Journal of Marketing 70 (4): 154–169.

Skitka, L.J., C.W. Bauman, and E.G. Sargis. 2005. Moral conviction: Another contributor to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88 (6): 895–917.

Skitka, L.J., A.N. Washburn, and T.S. Carsel. 2015. The psychological foundations and consequences of moral conviction. Current Opinion in Psychology 6: 41–44.

Spiller, S.A., G.J. Fitzsimons, J.G. Lynch Jr., and G.H. McClelland. 2013. Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: Simple effects tests in moderated regression. Journal of Marketing Research 50 (2): 277–288.

Starbucks. 2017. Starbucks invests in next generation of Colombian coffee farmers. https://stories.starbucks.com/stories/2017/starbucks-invests-in-next-generation-of-colombian-coffee-farmers/

Stritch, J.M., M.J. Pedersen, and G. Taggart. 2017. The opportunities and limitations of using Mechanical Turk (Mturk) in public administration and management scholarship. International Public Management Journal 20 (3): 489–511.

Swaen, V., Vanhamme, J. 2004. See how ‘good’ we are: The dangers of using corporate social activities in communication campaigns. ACR North American Advances.

Tetlock, P.E., O.V. Kristel, S.B. Elson, M.C. Green, and J.S. Lerner. 2000. The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78 (5): 853–870.

Valle, G. 2019. Chick-fil-A’s many controversies, explained. Vox.com, November, 19. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/5/29/18644354/chick-fil-a-anti-gay-donations-homophobia-dan-cathy

Wagner, T., R.J. Lutz, and B.A. Weitz. 2009. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing 73 (6): 77–91.

Wang, W., Korschun, D. 2015. Spillover of social responsibility associations in a brand portfolio. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Wheeler, S.C., R.E. Petty, and G.Y. Bizer. 2005. Self-schema matching and attitude change: Situational and dispositional determinants of message elaboration. Journal of Consumer Research 31 (4): 787–797.

Winkielman, P., N. Schwarz, T. Fazendeiro, and R. Reber. 2003. The hedonic marking of processing fluency: Implications for evaluative judgment. The Psychology of Evaluation: Affective Processes in Cognition and Emotion 189: 217.

Yaffe-Bellany, D. 2019. Chick-fil-a stops giving to 2 groups criticized by L.G.B.T.Q. Advocates. The New York Times, November 18. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/18/business/chick-fil-a-donations-lgbtq.html

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Study 1 Stimuli

Jones and Thompson is an international clothing company that owns a famous clothing brand J&T. Though you might not be familiar with the J&T brand as it is not available in the USA, it is a popular brand in other parts of the world. J&T recently launched a new initiative under which the brand has decided to double its yearly budget allocated to combat climate change.

On the next page, you will see an excerpt from a newspaper article in which J&T's CEO is sharing his thoughts about this new initiative. Please read the CEO’s statement carefully to answer the questions that follow.

“No Justification” condition

We are pleased to announce that J&T has decided to double its yearly budget allocated to combat climate change.

“Values-based Justification” condition

We are pleased to announce that J&T has decided to double its yearly budget allocated to combat climate change. The company has an obligation to contribute to the communities we operate in irrespective of whether we are required to do so or not. It is simply the right thing to do. J&T’s guiding principle is to fulfill our duty as a member of the society, and this decision would give us an opportunity to do just that.

Study 3 Stimuli

Jones and Thompson is an international clothing company that owns a famous clothing brand J&T. Though you might not be familiar with the J&T brand as it is not available in the USA, it is a popular brand in other parts of the world. On the next page, you will see an excerpt from a newspaper article published last year in which J&T's CEO is sharing his thoughts about a new initiative under which J&T has doubled its yearly budget allocated to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives.

Please read the CEO's statement carefully.

“No Justification” condition

We are pleased to announce that J&T has decided to double its yearly budget allocated to Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives.

“Values-based Justification” condition

We are pleased to announce that J&T has decided to double its yearly budget allocated to Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives. The company has an obligation to contribute to the communities we operate in irrespective of whether we are required to do so or not. It is simply the right thing to do. J&T’s guiding principle is to fulfill our duty as a member of the society, and this decision would give us an opportunity to do just that

Now, you will see an excerpt from newspaper article about J&T published today. Please read the excerpt carefully to answer the questions that follow.

J&T lags behind other clothing brands in CSR efforts

Though clothing brands have been at the forefront of CSR initiatives, J&T lags behind its peers in terms of its investments in CSR. Though J&T has been a successful brand in the clothing category, other similarly successful brands in the category have done much more to fulfill their CSR obligations.

Appendix 2

Measurement items by study.

Construct | Wording of measurement items (on 7-point scales) | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Perceived moralization (Kreps and Monin 2014) | Please rate your agreement with the following statements about J&T’s attitude toward this initiative… | |||

J&T feels a sense of moral conviction when thinking about this proposal | ||||

Morality is irrelevant to J&T’s attitude about this proposal. (R) | ||||

J&T's attitude about this proposal is tied to core moral values and beliefs | ||||

This proposal presents a moral issue for J&T |

Coefficient α | 0.80 | 0.73 | X | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Perceived commitment (Kreps and Monin 2014) | Please rate your agreement with the following statements about J&T’s attitude toward this initiative… | |||

J&T would invest a lot of effort to make this initiative successful | ||||

J&T would continue this initiative in the long term | ||||

J&T is committed to supporting this initiative |

Coefficient α | 0.85 | 0.84 | X | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Attitude toward the brand | Please rate your attitude toward the J&T brand | |||

(Dis)like, (un)favorable, bad/good | ||||

Coefficient α | 0.97 | 0.95 | X | |

Perceived hypocrisy (Wagner et al. 2009) | Please rate your agreement with the following statements about J&T | |||

J&T acts hypocritically | ||||

What J&T says and does are two different things | ||||

J&T pretends to be something that it is not | ||||

J&T does exactly what it says | ||||

J&T keeps its promises | ||||

J&T puts its words into action |

Coefficient α | X | X | 0.91 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Respondents’ formalism (Love et al. 2015) | Please answer the questions below according to how strongly you agree or disagree with the statements… | |||

Solutions to ethical problems are usually black and white | ||||

A person's actions should be described in terms of being right or wrong | ||||

A nation should pay the most attention to its heritage, its roots | ||||

Societies should follow stable traditions and maintain a distinctive identity | ||||

Uttering a falsehood is wrong because it wouldn't be right for anyone to lie | ||||

Unethical behavior is best described as a violation of some principle of the law |

Coefficient α | X | 0.74 | 0.79 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Respondents’ consequentialism (Love et al. 2015) | When people disagree over ethical matters, I strive for workable compromises | |||

When thinking of ethical problems, I try to develop practical, workable alternatives | ||||

It is of value to societies to be responsive and adapt to new conditions as the world changes | ||||

Solutions to ethical problems usually are seen as some shade of gray | ||||

When making an ethical decision, one should pay attention to others’ needs, wants and desires | ||||

The purpose of the government should be to promote the best possible life for its citizens |

Coefficient α | X | 0.72 | 0.73 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Respondents’ support for CSR (Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) | I strongly believe that companies should support Social Responsibility initiatives | |||

I think companies have the responsibility to enhance the well-being of the communities in which they operate | ||||

Companies have an obligation to be socially responsible | ||||

Coefficient α | X | 0.9 | X |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Love, E., Sekhon, T. & Salinas, T.C. Do well, do good, and know your audience: the double-edged sword of values-based CSR communication. J Brand Manag 29, 598–614 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-022-00282-w

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-022-00282-w