Abstract

Faced with the need to constantly find new growth drivers, luxury brands increasingly use cross-gender extensions (extension from the female to the male market and vice versa). Because of the lack of research on this topic, the aim of this article is to analyse the potential for cross-gender extension. We adopt a long-term perspective by analysing the discourse being directly produced by brands. We use a structural semiotic approach to define brand narratives and contracts and their level of openness. Seven luxury brands have been studied: Audemars Piguet, Cartier, Chanel, Dior, Hugo Boss, Montblanc and Rolex. The results show that they do not all have the same legitimacy for extension from the male to female market and vice versa. Specifically, in the context of cross-gender extensions, rather than brand extension potential (to new product categories), the narratives related to contracts of determination (linked to characters, gender and state) can determine the success or the failure of cross-gender extensions. We find that brands anchored in open determination contracts, i.e. those whose values are desired by both sexes (men and women), will be extended more easily from one market to another.

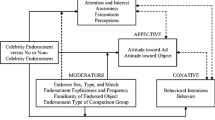

(Reproduced with permission from Veg-Sala and Roux 2014)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A study of a convenience sample of 30 people was conducted specially for this research to define the perceived gender of Chanel and Dior. The sample is composed of luxury consumers, 16 men and 14 women, aged from 29 to 55. Gender was measured using two 7-point Likert scales (a scale of femininity and a scale of masculinity). Chanel and Dior were both rated as very feminine (for Chanel M = 6.07 and for Dior M = 5.87) and not masculine (for Chanel M = 1.93 and for Dior M = 2.47). The mean comparison tests show that there is no significant difference between the perceived femininity (t = − 0.587, p = 0.567) and masculinity of both brands (t = 1.468, p = 0.164).

References

Aaker, D.A. 1996. Building strong brands. New York: Free Press Business.

Aaker, D.A., and K.L. Keller. 1990. Consumer evaluations of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing 54(January): 27–41.

Albrecht, C.M., C. Backhaus, H. Gurzki, and D.M. Woisetschläger. 2013. Drivers of brand extension success: What really matters for luxury brands. Psychology & Marketing 30(8): 647–659.

Alreck, P. 1994. Commentary: A new formula for gendering products and brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management 3(1): 6–18.

Alreck, P.L., R.B. Settle, and M.A. Belch. 1982. Who responds to gendered ads, and how? Journal of Advertising Research 22: 25–32.

Avery, J. 2012. Defending the markers of masculinity: Consumer resistance to brand gender-bending. International Journal of Research in Marketing 29: 322–336.

Azar, S. 2009. Rethinking brand feminine dimension: Brand femininity or femininities? In 38th EMAC conference, Nantes, France.

Azar, S. 2013. Exploring brand masculine patterns: Moving beyond monolithic masculinity. Journal of Product and Brand Management 22(7): 502–512.

Azar, S. 2015. Toward an understanding of brand sexual associations. Journal of Product and Brand Management 24(1): 43–56.

Bem, S. 1974. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42(2): 155–162.

Bourdieu, P. 2001. Masculine domination (trans: Richard Nice). Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Buil, Isabel, Eva Martinez et Leslie de Chernatony. 2007. Brand extension effects on brand equity: A cross-national study. In Thought Leaders International Conference on Brand Management, Birmingham Business School, April, 24–25th.

Conejo, F., and B. Wooliscroft. 2014. Brands defined as semiotic marketing systems. Journal of Macromarketing 35(3): 287–301.

De Barnier, V., S. Falcy, and P. Valette-Florence. 2012. Do consumers perceive three levels of luxury? A comparison of accessible, intermediate and inaccessible luxury brands. Journal of Brand Management 19: 623–636.

De Chernatony, L. 1999. Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 157–179.

Debevec, K., and E. Iyer. 1986. Sex roles and consumer perceptions of promotions, products, and self. What do we know and where should we be headed? Advances in Consumer Research 13: 210–214.

Evangeline, S.J., and V.R. Ragel. 2016. The role of consumer perceived fit in brand extension acceptability. Journal of Brand Management 13(1): 57–72.

Floch, J.M. 1988. The contribution of structural semiotics to the design of a hypermarket. International Journal of Research Marketing 4(3): 233–253.

Floch, J-M. 2000. Visual identities (trans: P. Van Osselaer and A. McHoul). Continuum, London.

Floch, J-M. 2001. Semiotics, marketing and communication: Beneath the signs, the strategies (trans: R. Bodkin). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Freire, A.N. 2014. When luxury advertising adds the identitary values of luxury: A semiotic analysis. Journal of Business Research 67: 2666–2675.

Fry, J. 1971. Personality variables and cigarette brand choice. Journal of Marketing Research 8: 289–304.

Fugate, D.L., and J. Phillips. 2010. Product gender perceptions and antecedents of product gender congruence. Journal of Consumer Marketing 27(2): 251–261.

Grayson, K., and D. Shulman. 2000. Indexicality and the verification function of irreplaceable possessions: A semiotic analysis. Journal of Consumer Research 27: 17–30.

Greimas, A., and J. Courtès. 1982. Semiotics and language: An analytical dictionary (trans: L. Crist et al.). Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Grohmann, B. 2009. Gender dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research 46(2): 105–119.

Hagtvedt, H., and V.M. Patrick. 2009. The broad embrace of luxury: Hedonic potential as a driver of brand extendibility. Journal of Consumer Psychology 19: 608–618.

Helgeson, V.S. 1994. Prototypes and dimensions of masculinity and femininity. Sex Roles 31(11/12): 653–682.

Jung, K., and W. Lee. 2006. Cross-gender brand extensions: Effects of gender of the brand, gender of consumer, and product type on evaluation of cross-gender extensions. Advances in Consumer Research 33: 67–74.

Jung, K., and L. Tey. 2010. Searching for boundary conditions for successful brand extensions. Journal of Product and Brand Management 19(4): 276–285.

Kapferer, J.N. 2004. The new strategic brand management. London: Kogan Page.

Kapferer, J.N. 2015. The future of luxury: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Brand Management 21(9): 716–726.

Kapferer, J.N., and G. Laurent. 2016. Where do consumers think luxury begins? A study of perceived minimum price for 21 luxury goods in 7 countries. Journal of Business Research 69: 332–340.

Keller, K.L. 2009. Managing the growth tradeoff: Challenges and opportunities in luxury branding. Brand Management 16(5/6): 290–301.

Kevin, Lane Keller, and David A. Aaker. 1992. The effects of sequential introduction of brand extensions. Journal of Marketing Research 29(1): 35.

Lieven, T., B. Grohmann, A. Herrmann, J.R. Landwehr, and M. Van Tilburg. 2014. The effect of brand gender on brand equity. Psychology & Marketing 31(5): 371–385.

Loken, B., and D. Roedder John. 1993. Diluting brand beliefs: When do brand extensions have a negative impact? Journal of Marketing 57(July): 71–84.

Magnoni, F., and E. Roux. 2012. The impact of step-down line extension on consumer-brand relationships: A risky strategy for luxury brands. Journal of Brand Management 19(7): 595–608.

Martinez, E., and L. de Chernatony. 2004. The effect of brand extension strategies upon brand image. Journal of Consumer Marketing 21(1): 39–50.

McCracken, G. 1986. Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research 13(June): 71–84.

McCracken, G. 1993. The value of the brand: An anthropological perspective. In Brand equity & advertising: Advertising’s role in building strong brands, ed. D. Aaker, and A.L. Biel, 125–139. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mervis, C.B., and E. Rosh. 1981. Categorization of natural objects. Annual Review of Psychology 32: 89–115.

Mick, D.G., and L. Oswald. 2006. The semiotic paradigm on meaning on the marketplace. In Handbook of qualitative methods in marketing, ed. R. Belk. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Mick, D.G., J.E. Burroughs, P. Hetzel, and M.Y. Brannen. 2004. Pursuing the meaning of meaning in the commercial world: An international review of marketing and consumer research founded on semiotics. Semiotica 152(1/4): 1–74.

Monga, A.B., and D.R. John. 2010. What makes brands elastic? The influence of brand concept and styles of thinking on brand extension evaluation. Journal of Marketing 74: 80–92.

Morris, G.P., and E.W. Cundiff. 1971. Acceptance by males of feminine products. Journal of Marketing Research 8: 372–374.

Ogilvie, M., and K. Mizerski. 2011. Using semiotics in consumer research to understand everyday phenomena. International Journal of Market Research 53(5): 651–668.

Oswald, L. 2012. Marketing semiotics: Signs, strategies, and brand value. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ourahmoune, N., A.S. Binninger, and I. Robert. 2014. Brand narratives, sustainability, and gender: A socio-semiotic approach. Journal of Macromarketing 34(September): 313–331.

Park, C.W., S. Milberg, and R. Lawson. 1991. Evaluation of brand extensions: The role of product feature similarity and brand concept consistency. Journal of Consumer Research 18(September): 185–193.

Reddy, M., N. Terblanche, L. Pitt, and M. Parent. 2009. How far can luxury brands travel? Avoiding the pitfalls of luxury brand extension. Business Horizons 52: 187–197.

Remaury, B. 2004. Marques et récits: La marque face à l’imaginaire culturel contemporain. Paris: Institut Français de la Mode, Editions du Regard.

Rokeach, M. 1960. The open and closed mind. New York: Basic Book.

Roper, S., R. Caruana, D. Medway, and P. Murphy. 2013. Constructing luxury brands: Exploring the role of consumer discourse. European Journal of Marketing 47(3/4): 375–400.

Roux, E., and D.M. Boush. 1996. The role of familiarity and expertise in luxury brand extension. In Proceedings of 25th EMAC Conference, Budapest, May 14–17, 2053–2061.

Selvanayagam, J. Evangeline, and V.R. Ragel. 2015. Consumer acceptability of brand extensions: The role of brand reputation and perceived similarity. Journal of Brand Management 12(3): 18–29.

Spiggle, S., H.T. Nguyen, and M. Caravella. 2012. More than fit: Brand extension authenticity. Journal of Marketing Research 49(December): 967–983.

Stern, B. 1995. Consumer myths: Frye’s taxonomy and the structural analysis of consumption text. Journal of Consumer Research 22(September): 165–185.

Stokburger-Sauer, N.E., and K. Teichmann. 2013. Is luxury just a female thing? The role of gender in luxury brand consumption. Journal of Business Research 66(7): 889–896.

Stuteville, J. 1971. Sexually polarized products and advertising strategy. Journal of Retailing 47(2): 3–13.

Till, B.D., and R.L. Priluck. 2001. Conditioning of meaning in advertising: Brand gender perception effects. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising 23(2): 1–8.

Uggla, H. 2016. Leveraging luxury brands: Prevailing trends and research challenges. Journal of Brand Management 13(1): 34–41.

Ulrich, I. 2013. The effect of consumer multifactorial gender and biological sex on the evaluation of cross-gender brand extensions. Psychology & Marketing 30(9): 794–810.

Ulrich, I., E. Tissier-Desbordes, P.L., Dubois. 2010. Brand gender and its dimensions. In Advances in consumer research—European conference, London, vol. 9, 136–143.

Veg-Sala, N. 2014. The use of longitudinal case studies and semiotics for analyzing brand development as process of assimilation or accommodation. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 14(4): 373–392.

Veg-Sala, N., and E. Roux. 2014. A semiotic analysis of the extendibility of luxury brands. Journal of Product and Brand Management 23(2): 103–113.

Vigarello, G. 2004. Histoire de la beauté, Le corps et l’art de l’embellir, de la renaissance à nos jours. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Vigarello, G., and F. Giust-Desprairies. 2014. Masculin/Féminin: Le changement dans la matérialité des corps. Nouvelle Revue de Psychologie 1(17): 177–187.

Viot, C. 2011. Can brand identity predict brand extensions’ success or failure? Journal of Product and Brand Management 20(3): 216–227.

Vitz, P., and D. Johnston. 1965. Masculinity of smokers and the masculinity of cigarette images. Journal of Applied Psychology 49(3): 155–159.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veg-Sala, N., Roux, E. Cross-gender extension potential of luxury brands: a semiotic analysis. J Brand Manag 25, 436–448 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0094-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0094-4