Abstract

Aid donors and recipients have long been concerned that aid inflows may lead to an appreciation of the real exchange rate and an associated loss of competitiveness. This paper provides new evidence of the dynamic effects of aid on the real exchange rate, using an identification strategy that exploits the long delays between the approval of aid projects and the subsequent disbursements on them. These disbursement delays enable the isolation of a source of variation in aid inflows that plausibly is uncorrelated with contemporaneous macroeconomic shocks that may drive both aid and the real exchange rate. Using this predetermined component of aid as an instrument, there is little evidence that aid inflows lead to significant real exchange rate appreciations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The main data constraint is the multilateral trade-weighted real exchange rate data series from the IMF that is only available from 1979 whereas the other core variables are available from 1970 onward.

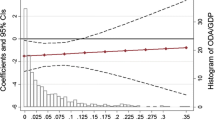

For example, the local projections methodology does not require us to take a stand on the empirically vexing issue of whether the real exchange rate has a unit root or not, since the local projections simply are estimates of the conditional expectation of the real exchange rate at t+h conditional on information available at t−1

Another potential source of endogeneity is the result of the combination of country fixed effects and a lagged dependent variable. The “within-group” transformation implied by the fixed effects estimator introduces a mechanical correlation between the transformed error term and lagged dependent variable. This correlation becomes negligible as the time-series dimension becomes large. Monte Carlo evidence in Judson and Owen (1999) suggests a bias in the fixed effects estimator of only about 1–3 percent of the true value of β when T=20 (their Table 1). Although they do report larger biases in the fixed-effects estimator of the coefficient on the lagged dependent variable of 12–17 percent of the true parameter value, this parameter is not our main interest. In our setting, the median number of time series observations per country is T=28.

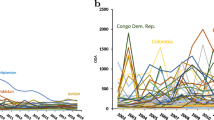

The predicted disbursements instrument is constructed as follows. We start with a set of approximately 60,000 loans from official creditors to developing country governments, as recorded in the Debtor Reporting System database of the World Bank. For each loan we have the year of the original commitment, and the schedule of subsequent annual actual disbursements. For each loan we construct a 10-year disbursement profile, that is, the fraction of the original commitment that is disbursed in year 0, 1, 2, …, 10, with year zero corresponding to the approval year of the loan. We next sort loans into creditor-decade-region-specific bins and average disbursement profiles across loans within bins. We then apply these typical disbursement profiles to individual loans within each bin, and construct predicted disbursements for each loan, that is, the disbursements that would have occurred had the loan disbursed at the typical rate for all loans in the same bin. The rationale for this step is that it removes any country-specific source of variation in actual disbursements on previously approved loans, which might respond endogenously to contemporaneous macroeconomic shocks. Finally, we aggregate the predicted disbursements across all loans for each country-year observation, but excluding loans approved in the same year. By construction, the only country-specific variation in this predicted disbursements measure reflects loan approval decisions from previous years, which we assume to be uncorrelated with contemporaneous macroeconomic shocks. For details, see Sections 2 and 3 of Kraay (2014).

A companion paper, Kraay (2013) extends the methodology in Kraay (2012 and 2014) to develop an analogous instrument for grant-financed aid.

We obtain qualitatively similar results if we use the more widely available bilateral real exchange rate, based on nominal exchange rates relative to the U.S. and relative price levels as measured by GDP deflators. Details are available in the working paper version of this paper (Jarotschkin and Kraay, 2013).

More formally, for our benchmark specification we also calculate weak-instrument consistent confidence sets based on inversion of the Anderson-Rubin statistic and find that they are nearly identical to conventional confidence intervals based on Wald statistics.

To conserve on space we report the coefficient on approvals of slow-disbursing loans only for the h=0 local projection regression.

In fact, see Korinek and Serven (2010) for a model in which governments can use reserve accumulation as a tool to undervalue the real exchange rate, in order to benefit from dynamic learning-by-doing effects in the production of tradeables.

We classify the exchange rate regime as fixed where their “coarse” measure is equal to 1 or 2, corresponding to fixed or slowly crawling pegs, and flexible otherwise.

Although not reported for reasons of space, we do find that reserve accumulation is negatively correlated with changes in the real exchange rate, although generally not significantly so. This is consistent with the mechanism discussed above: if capital inflows go to reserve accumulation rather than being spent domestically on nontradeables, the effect on the real exchange rate will be smaller. Hence, when we control for reserve accumulation we eliminate this source of downward bias in the estimated effect of aid on the real exchange rate. Moreover, the significant result in horizon=3 in the IDA sample is driven by a handful of influential observations. Applying the Hadi procedure leads to a similar result as in the benchmark specification for this sample in this horizon but leaves the coefficient insignificant.

References

Adam, Chris S., 2006, “Exogenous Inflows and Real Exchange Rates: Theoretical Quirk or Empirical Reality?,” in The Macroeconomic Management of Foreign Aid: Opportunities and Pitfalls, ed. by Peter Isard, Leslie Lipschitz, Alexandros Mourmouras, and Boriana Yontcheva (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund).

Bulir, Ales and Timothy Lane, 2006, “Aid and Fiscal Management,” in Macroeconomic Policies and Poverty Reduction. Routledge Studies in the Modern World Economy, Vol. 53, ed. by Mody Ashoka, and Catherine Patillo (London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis), pp. 126–50.

Christiansen, Lone, Alessandro Prati, Luca Ricci, and Thierry Tressel, 2009, “External Balance in Low Income Countries.” IMF Working Paper No. WP/09/221.

Corden, W. Max and Peter J. Neary, 1982, “Booming Sector and De-Industrialization in a Small Open Economy,” Economic Journal, Vol. 92, No. 368, pp. 825–48.

Elbadawi, A.I., 1999, “External Aid: Help or Hindrance to Export Orientation in Africa?,” Journal of African Economies, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 578–616.

Hussain, Mumtaz, Andrew Berg, and Shekhar Aiyar, 2009, “The Macroeconomic Management of Increased Aid: Policy Lessons from Recent Experience,” Review of Development Economics, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 491–509.

Hadi, A.S., 1992, “Identifying Multiple Outliers in Multivariate Data,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 761–71.

Ilzetzki, Ethan, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Kenneth S. Rogoff, 2012, “Exchange Rate Arrangements Entering the 21st Century: Which Anchor Will Hold?” updated through December 2010, available at http://personal.lse.ac.uk/ilzetzki/index.htm/Data.htm.

Jarotschkin, Alexandra and Aart Kraay, 2013, “Aid, Disbursement Delays, and the Real Exchange Rate,” World Bank Policy Research Department Working Paper No. 6501.

Jordà, Oscar, 2005, “Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections,” American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No. 1, pp. 161–82.

Judson, Ruth and Ann Owen, 1999, “Estimating Dynamic Panel Models: A Guide for Macroeconomists,” Economics Letters, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 9–15.

Kraay, Aart, 2013, “Disbursement Delays and the Growth Effects of Aid,” Manuscript (The World Bank).

Kraay, Aart, 2012, “How Large is the Government Spending Multiplier? Evidence from World Bank Lending,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 127, No. 2, pp. 829–87.

Kraay, Aart, 2014, “Government Spending Multipliers in Developing Countries. Evidence from Lending by Official Creditors,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 170–208.

Korinek, Anton and Luis Serven, 2010, “Undervaluation through Foreign Reserve Accumulation: Static Losses, Dynamic Gains,” Policy Research Working Paper 5250 (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Prati, Alessandro, Ratna Sahay, and Thierry Tressel, 2003, “Is there a Case for Sterilizing Foreign Aid,” Working paper preliminary draft presented at the 18th Annual European Economic Association Congress and the 58th Econometric Society European Meeting, Stockholm, August 20–24.

Rajan, Raghuram and Arvind Subramanian, 2011, “Aid, Dutch Disease, and Manufacturing Growth,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 94, No. 1, pp. 106–18.

Rodrik, Dani, 2008, “The Real Exchange Rate and Economic Growth,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2008, pp. 365–412.

Staiger, Douglas and James Stock, 1997, “Instrumental Variables Regression with Weak Instruments,” Econometrica, Vol. 65, No. 3, pp. 557–86.

Temple, Jonathan R.W., 2010, “Aid and Conditionality,” in Handbook of Development Economics, Vol. 5 (London: Elsevier), pp. 4415–4523.

Torvik, Ragnar, 2001, “Learning by Doing and the Dutch Disease,” European Economic Review, Vol. 45, No. 2, pp. 285–306.

Van Wijnbergen, Sweder, 1986, “Macroeconomic Aspects of the Effectiveness of Aid: On the Two-Gap Model, Home Goods Disequilibrium, and Real Exchange Rate Misalignment,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 21, No. 1–2, pp. 123–36.

Yano, Makoto and Jeffrey B. Nugent, 1999, “Aid, Nontraded Goods, and the Transfer Paradox in Small Countries,” American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3, pp. 431–49.

Additional information

*Alexandra Jarotschkin is a PhD candidate at Paris School of Economics - EHESS. Aart Kraay is an economist in the Development Research Group of the World Bank. The authors are grateful to Oscàr Jordà and Luis Serven for helpful comments, and to Nanasamudd Chhim, Evis Rucaj, Shelley Lai Fu, and Ibrahim Levent for their assistance with the Debtor Reporting System data used in this paper. Financial support from the Knowledge for Change Program (KCP) of the World Bank is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed here are the authors’, and do not reflect those of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.