Abstract

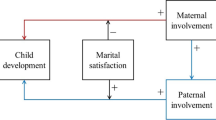

I examine if the documented positive relationship between marriage and child outcomes represents a maternal life satisfaction effect. By treating life satisfaction and marital status as endogenous in the skill production process, I show that there is a distinct happiness and a distinct marriage effect; marriage increases cognitive skills and decreases conduct problems, while maternal happiness increases social and self-regulation skills to an equivalent of up to £ 38,000 per year. Thus, promoting healthy and happy marriages can be more effective than policies that promote marriage, and life satisfaction is an avenue through which non-married mothers can produce high quality children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Frey and Stutzer [2002] find evidence in favor of a causal effect of marriage on life satisfaction as marriage permanently increases happiness, while Easterlin [2003] concludes that there is only partial evidence of a causal effect as marriage only slightly increases happiness.

For mechanisms through which marriage may cause happiness, see Waite and Lehrer [2003]; for mechanisms on how life satisfaction can lead to marriage, see Veenhoven [1997]; and for mechanisms on how marriage can affect child outcomes, see Weiss [1997].

Proto et al. [2011] examine the relationship between happiness, marital status, and child outcomes, but without identifying causal effects. Using an experiment they show that parental divorce does not affect college students’ cognitive skills, and conclude that parental experiences do not pass on through genes to child productivity.

For example, a highly motivated child will perform better on standardized tests compared to an equally cognitive able child but with a lower level of motivation.

S j,t−1 −k reduces the correlation between life satisfaction and unobserved family inputs and skill. Even if the lagged measure of a child outcome does not completely meet the criteria to be a sufficient statistic for past inputs, the vector of these six additional lagged skill measures should be an adequate sufficient statistic for past inputs and endowments.

I include current crime rates to account for the possibility that incarceration rates may be due to a shift of male preferences towards higher criminal behavior, which directly exposes the children to crime in their area. We do not know a priori if mothers will choose the high or low incarceration rate regions as they may choose the amenity of low incarceration rates to have a safer environment for their children, or they may choose the higher incarceration rate region to receive higher compensations for the undesirable unsafe environment.

Only for cohabitation there is evidence that incarceration rates affect differently college graduates and non-college graduates as the difference is statistically significant. However, there are no statistically significant differences for any of the three marital status groups when examining high school dropouts vs high school graduates, and mothers at the lowest 10th percentile of the income distribution vs all other income groups.

Prior studies have documented that there is sufficient variation between marital status and life satisfaction as, on average, 40–50 percent of the variation in life satisfaction is explained by socioeconomic characteristics [e.g., Lykken and Tellegen 1996]. Even though marital status is one of the factors that explain a significant portion of life satisfaction, it is also not the sole characteristic that determines happiness [e.g., Dolan et al. 2008].

The differences are not statistically significant between single and cohabiting or married and divorced for prosocial skills, single and divorced for emotional symptoms, divorced and cohabiting for hyperactivity, and among single, divorced and cohabiting for self-regulation skills.

Northeast, Northwest, Yorkshire and Humber, East Midlands, West Midlands, East of Anglia, London, Southeast, Southwest, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

I also predicted how much the happiness of a single mother would have to change to counteract the effects of marriage on each child outcome. Happiness of single mothers would have to increase by 36.1 percent to offset the beneficial impact of marriage on conduct problems, while happiness would have to increase by 2.668 percent to offset the positive effects of marriage on cognitive skills. This last finding suggests that, since cognitive skills are to a large extent genetically determined, improving maternal happiness would not be the best possible pathway to tackle deficiencies in such skills. The predicted change in happiness is 7.4 percent for emotional symptoms, 26.5 percent for hyperactivity, 49.8 percent for peer problems, 1.2 percent for prosocial behaviors, and 5.6 percent for self-regulation skills.

The positive effect of divorce is consistent with recent findings that divorce increases personal well-being because it removes the individual from a stressful relationship [e.g., Gardner and Oswald 2006; Amato and Hohmann-Marriott 2007].

It is possible that the negative coefficient at age 5 for time spent with children reflects the additional care that children with disabilities may need. Repeating the analysis for a sample of children with disabilities and a sample for non-disabled children, I find that the coefficients of maternal time with the child at age are negative for conduct, emotional, hyperactivity, and peer problems, and positive for the prosocial behaviors and independence. However, the difference in the estimated coefficients were not statistically significant. Therefore, even when we explicitly control for the amount of time the mothers devote to their children based on their disability status there are no significant differences in their time allocation decisions.

In results available upon request I show that maternal skills are a major confounding factor when estimating the effect of maternal life satisfaction on child skills. This finding is in contrast to Berger and Spiess [2011] who report that maternal personality is not a confounding factor for most skills (apart from social skills). However, the estimated effect of maternal life satisfaction on child outcomes is only slightly due to the type of maternal investments, the amount of time the mother spends with her child, parenting practices, and friend networks. The life satisfaction effects decrease conditional on mother–child quality measures (which may reflect the quality of the attachment to the child) with a similar change observed for the quality of spousal relationship (which captures the quality of the familial environment).

References

Almlund, M., A.L. Duckworth, J.J. Heckman, and T. Kautz. 2011. Personality Psychology and Economics. in Handbook of The Economics of Education. edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin and Ludger Woessmann. Volume 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1–181.

Amato, P.R. 2005. The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social and Emotional Well-being of the Next Generation. The Future of Children, 15(2): 75–92.

Amato, P.R., and B. Hohmann-Marriott. 2007. A Comparison of High- and Low-distress Marriages that End in Divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3): 621–638.

Argyle, M. 1999. Causes and Correlates of Happiness. in Well-being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. edited by Daniel Kahneman, Ed Diener and Norbert Schwarz. New York: Russell Stage, 173–187.

Becker, G.S. 1973. A Theory of Marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81(4): 813–846.

Belsky, J. 1997. Classical and Contextual Determinants of Attachment Security. in Development of Interaction and Attachment: Traditional and Non-traditional Approaches. edited by Willem Koops, Jan B. Joeksma and Dymph C. van den Boom. Amsterdam: North Holland, 39–58.

Berger, E.M., and K.K. Spiess. 2011. Maternal Life Satisfaction and Child Outcomes: Are They Related? Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(1): 142–158.

Binder, M., and A. Coad. 2010. An Examination of the Dynamics of Well-being and Life Events Using Vector Autoregressions. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 76(2): 352–371.

Binder, M., and F. Ward. 2011. The Structure of Happiness: A Vector Autoregressive Approach. Papers on Economics and Evolution No.1108, Max Plank Institute of Economics.

Borghans, L., H. Meijers, and Bas ter Weel. 2008. The Role of Noncognitive Skills in Explaining Cognitive Test Scores. Economic Inquiry, 46(1): 2–12.

Bowden, R.J., and D.A. Turkington. 1981. A Comparative Study of Instrumental Variables Estimators for Nonlinear Simultaneous Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76(376): 988–995.

Bowden, R.J., and D.A. Turkington. 1984. Instrumental Variables. New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Canli, T., and K.-P. Lesch. 2007. Long Story Short: The Serotonin Transporter in Emotion Regulation and Social Cognition. Nature Neuroscience, 10(9): 1103–1109.

Charles, K.K., and M.C. Luoh. 2010. Male Incarceration, the Marriage Market and Female Outcomes. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(3): 614–627.

Connolly, M. 2013. Some Like It Mild and Not Too Wet: The Influence of Weather on Subjective Well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(2): 457–473.

Cooper, C.E., Cynthia A. Osborne, Audrey N. Beck, and Sara S. McLanahan. 2011. Partnership Instability, School Readiness, and Gender Disparities. Sociology of Education, 84(3): 246–259.

Crawford, C., A. Goodman, E. Greaves, and J. Robert. 2011. Cohabitation, Marriage, Relationship Stability and Child Outcomes: An Update. IFS Commentary C120, Institute for Fiscal Studies: Nutfield Foundation.

Cunha, F., and J.J. Heckman. 2008. Formulating, Identifying, and Estimating the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skills Formation. Journal of Human Resources, 43(4): 738–782.

Cunha, F., J.J. Heckman, and S.M. Schennach. 2010. Estimating the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Formation. Econometrica, 78(3): 883–931.

Dahl, G., and L. Lochner. 2012. The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. American Economic Review, 102(5): 1927–1956.

Denissen, J.J.A., L. Butalid, L. Penke, and M.A.G. van Aken. 2008. The Effects of Weather on Daily Mood: A Multilevel Approach. Emotion, 8(5): 662–667.

Diener, E., H.L. Smith, and F. Fujita. 1995. The Personality Structure of Affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1): 130–141.

Diener, E., E.M. Suh, R.E. Lucas, and H.L. Smith. 1999. Subjective Well-being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2): 276–302.

Dolan, P., T. Peasgood, and M. White. 2008. Do We Really Know What Makes Us Happy? A Review of the Economic Literature on the Factors Associated with Subjective Well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1): 94–122.

Easterlin, R.A. 2003. Explaining Happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(19): 11176–11183.

Emery, R.E., and D.K. O’Leary. 1982. Children’s Perceptions of Marital Discord and Behavior Problems of Boys and Girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 10(1): 11–24.

Felfe, C., and A. Hsin. 2009. The Effect of Maternal Work Conditions on Child Development. Working Paper Series 2009–32. Department of Economics, University of St. Gallen.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., and P. Frijters. 2004. How Important Is Methodology for the Estimates of the Determinants of Happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497): 641–659.

Finlay, K., and D. Neumark. 2010. Is Marriage Always Good for Children? Evidence from Families Affected by Incarceration. Journal of Human Resources, 45(4): 1046–1088.

Flouri, E., and A. Buchanan. 2003. The Role of Father Involvement in Children’s Later Mental Health. Journal of Adolescence, 26(1): 63–78.

Fomby, P., and S.J. Bosick. 2013. Family Instability and the Transition to Adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5): 1266–1287.

Fomby, P., and C. Osborne. 2010. The Influence of Union Stability and Union Quality on Children’s Aggressive Behavior. Social Science Research, 39(5): 912–924.

Francesconi, M., S.P. Jenkins, and T. Siedler. 2010. Childhood Family Structure and Schooling Outcomes: Evidence for Germany. Journal of Population Economics, 23(3): 1073–1103.

Frey, B.S., and A. Stutzer. 2002. What Can Economics Learn from Happiness Research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2): 402–435.

Gardner, J., and A.J. Oswald. 2006. Do Divorcing Couples Become Happier By Breaking Up? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, Royal Statistical Society, 169(2): 319–336.

Ginther, D.K., and R.A. Pollak. 2004. Family Structure and Children’s Educational Outcomes: Blended Families, Stylized Facts, and Descriptive Regressions. Demography, 41(4): 671–696.

Goodman, R. 2001. Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11): 1337–1345.

Hanushek, E.A., and L. Woessmann. 2008. The Role of Cognitive Skills in Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(3): 607–668.

Hays, R.D., L.S. Morales, and S.P. Reise. 2000. Item Response Theory and Health Outcomes Measurement in the 21st Century. Medical Care, 38(Suppl.II): S28–S42.

Hill, V. 2005. Through the Past Darkly: A Review of the British Ability Scales Second Edition. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 10(2): 87–98.

Hill, M.S., W.-J.J. Yeung, and G.J. Duncan. 2001. Childhood Family Structure and Young Adult Behaviors. Journal of Population Economics, 14(2): 271–299.

Hoekstra, M.L. 2009. The Effects of Near and Actual Parental Divorce on Student Achievement and Misbehavior. Working Paper No. 305, Department of Economics, University of Pittsburgh.

Hofferth, S.L. 2006. Residential Father Family Type and Child Well-being: Investment versus Selection. Demography, 43(1): 53–77.

Keller, M.C., B.L. Fredrickson, O. Ybarra, S. Cote, K. Johnson, J. Mikels, A. Conway, and T. Wager. 2005. A Warm Heart and a Clear Head: The Contingent Effects of Weather on Mood and Cognition. Psychological Science, 16(9): 724–731.

Lang, K., and J.L. Zagorsky. 2001. Does Growing Up with a Parent Absent Really Hurt? The Journal of Human Resources, 36(2): 253–273.

Lykken, D., and A. Tellegen. 1996. Happiness Is a Stochastic Phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7(3): 186–189.

Magnuson, K., and L.M. Berger. 2009. Family Structure States and Transitions: Associations with Children’s Well-being During Middle Childhood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(3): 575–591.

McLanahan, S., and G.D. Sandefur. 1994. Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Ministry of Justice. 2013. Story of the Prison Population 1993–2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/story-of-the-prison-population-1993-2012.

Neidell, M.J. 2000. Early Parental Time Investments in Children’s Human Capital Development: Effects of Time in the First Year on Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Outcomes. Working Paper No.806, UCLA Department of Economics.

Osborne, C., and S. McLanahan. 2007. Partnership Instability and Child Well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(4): 1065–1083.

Proto, E., D. Sgroi, and A.J. Oswald. 2011. Are Happiness and Productivity Lower among University Students with Newly-divorced Parents? An experimental Approach. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4755, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Saint-Laurent, L., and A.-L. Fournier. 1993. Children with Intellectual Disabilities: Parents’ Satisfaction with School. Developmental Disabilities Bulletin, 21(1): 15–33.

Samejima, F. 1969. Estimation of a Latent Ability Using a Response Pattern of Graded Scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement no.17. Richmond, VA: Psychometric Society.

Stagner, M., J. Ehrle, K. Kortenkamp, and J. Reardon-Anderson. 2009. Systematic Review of the Impact of Marriage and Relationship Programs. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Stutzer, A., and B.S. Frey. 2006. Does Marriage Make People Happy, or Do Happy People Get Married? The Journal of Socio-economics, 35(2): 326–347.

Sun, Y., and Y. Li. 2011. Effects of Family Structure Type and Stability on Children’s Academic Performance Trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73(3): 514–556.

Tartari, M. 2015. Divorce and the Cognitive Achievement of Children. International Economic Review, 56(2): 597–645.

Upshur, C.C. 1991. Mothers’ and Fathers’ Ratings of the Benefits of Early Intervention Services. Journal of Early Intervention, 15(4): 345–357.

Veenhoven, R. 1997. Progre’ dans la Compre´hension du Bonheur [Progress in Understanding Happiness]. Revue Quebecoise de Psychologie, 18(2): 29–74.

Waite, L.J., and E.L. Lehrer. 2003. The Benefits from Marriage and Religion in the United States: A Comparative Analysis. Population and Development Review, 29(2): 255–275.

Weiss, Y. 1997. The Formation and Dissolution of Families: Why Marry? Who Marries Whom? And What Happens Upon Divorce? in Handbook of Population and Family Economics. Volume 1. edited by Mark R. Rosenzweig and Oded Stark Amsterdam: Elsevier, 81–123.

Zimmermann, A.C., and R.A. Easterlin. 2006. Happily Ever After? Cohabitation, Marriage, Divorce, and Happiness in Germany. Population and Development Review, 32(3): 511–528.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary information accompanies this article on the Eastern Economic Journal website (www.palgrave-journals.com/eej)

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nikolaou, D. Maternal Life Satisfaction, Marital Status, and Child Skill Formation. Eastern Econ J 43, 621–648 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2015.48

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2015.48